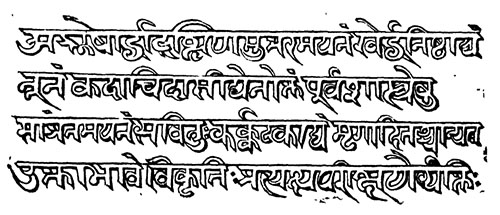

Chapter IV: The Structure of the Rgvedic Poems, Excerpt from A History of Indian literature: Vedic Literature (Samhitas and Brahmanas)

edited by Jan Gonda

Volume I, Fasc. 1

1975

The Rigveda is structured based on clear principles. The Veda begins with a small book addressed to Agni, Indra, Soma and other gods, all arranged according to decreasing total number of hymns in each deity collection; for each deity series, the hymns progress from longer to shorter ones, but the number of hymns per book increases. Finally, the meter too is systematically arranged from jagati [12 12 12 12 (syllables)] and tristubh [11 11 11 11 (syllables)] to anustubh [8 8 8 8 (syllables)] and gayatri [8 8 8 (syllables)] as the text progresses.

The rituals became increasingly complex over time, and the king's association with them strengthened both the position of the Brahmans and the kings. The Rajasuya rituals, performed with the coronation of a king, "set in motion [...] cyclical regenerations of the universe." In terms of substance, the nature of hymns shift from praise of deities in early books to Nasadiya Sukta with questions such as, "what is the origin of the universe?, do even gods know the answer?", the virtue of Dāna (charity) in society, and other metaphysical issues in its hymns.

-- Vedas, by Wikipedia

Chapter IV: The Structure of the Rgvedic Poems

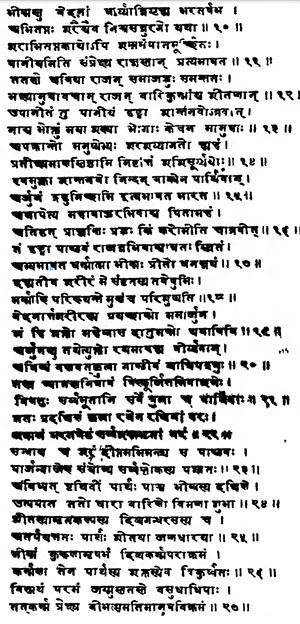

1. Stanzas and metres

The 'hymns' (sukta) of the Rgveda consist of stanzas ranging in number from three1 [There are some fragments, e.g. 1, 99 (consisting of one stanza); perhaps also 10, 176 and some other short hymns.] to fifty-eight (9, 97), but usually not exceeding ten or twelve2 [For a certain predilection for eleven stanzas: OLDENBERG, in ZDMG 38, p. 456 (= K. S. p. 530).]. The stanzas of all Vedic metrical texts are almost always complete in themselves and are composed in some fifteen different metres, only seven of which are frequent3 [In this section all technical details, in part very complicated, must for reasons of space be omitted. For an introduction see A. A. MACDONELL, A Vedic grammar for students, Oxford 1916 (3-1953), p. 436. The only comprehensive work of greater compass is in some respects antiquated: E. V. ARNOLD, Vedic metre in its historical development, Cambridge 1905, 2-Delhi 1967. For some particulars see, inter alia, ARNOLD in KZ 37, p. 213; BLOOMFIELD, in JAOS 27, p. 72; Repetitions p. 523; H. N. RANDLE, in BSOAS 20, p. 459; V. K. RAJWADE, at IHQ 19, p. 147. For references to metrics in the Vedic texts: WEBER, I. S. VII, p. 1.]. Three of them, used in about four-fifths of all stanzas in the Rgveda-Samhita, are by far the commonest, viz. the anustubh stanza [8 8 8 8 (syllables)] , consisting of four 'feet'4 [Not to be confused with the feet of Greek metrics; pada (sometimes translated by 'verse') means 'quarter' (from the foot of a quadruped).] (pada) of eight syllables each5 [Pada etc. were already mentioned in the Nidanasutra. (WEBER, I. S. VIII, p. 115).]; the tristubh [11 11 11 11 (syllables)], consisting of four times eleven; and the jagati [12 12 12 12 (sylables)], composed of four times twelve syllables6 [The number of syllables is not always strictly observed. Stanzas may also contain more or fewer quarters than four; the well-known gayatri for instance consists of three padas of eight.]. Stanzas are sometimes formed by combining units of different length. From the point of view of syntax and contents a half-stanza (verse or line) is very often a distinct unit7 [J. GONDA, Syntax and verse structure in the Veda, IL 1958 (R. Turner Jubilee Vol.), p. 35; Syntaxis en versbouw voornamelijk in het Vedisch. Amsterdam Acad. 1960; The anustubh stanzas of the Rgveda, ALB 31-32, p. 14.]; that means that a large majority of the stanzas is essentially bipartite [made by two separate parties.]8 [For syntactic and stylistic aspects see p. 211ff. Like the formation of longer units by the accumulation of single lines, the line as an individual unit seems to have been widely normal in songs and poems which are not accompanied by a dance.]

In illustration of the processes adopted by the poets to construct stanzas from lines and quarters containing short, single, condensed statements an analysis of the first half of RV. 1, 10, chosen at random may be inserted here. Stanza 1, a and b9 [The quarters are indicated by letters.] constitute two sentences, stating that the eulogists praise Indra and start a hymn; cd are one sentence, which paraphrases the same idea in poetical imagery. Two telescoped subordinate clauses in 2a and b are continued by a main clause (2c); 2d is a short independent sentence. Stanza 3ab and cd constitute two sentences connected by "then." The line 4ab consists of four short sentences (imperatives) equally distributed over the quarters; cd are one sentence, the verb of which is likewise an imperative. Stanza 5 constitutes one compound sentence -- cd are subordinate -- both parts of which are of equal length. In 6 the first pada is a complete short sentence, supplemented by the syntactically incomplete second; a similar structure recurs in the second line. Occasionally two stanzas are syntactically connected by means of a particle ("for, because" etc.); instances of enjambment beyond a line are comparatively infrequent; beyond the stanza they are very rare and sometimes wrongly assumed10 [Cf 1.8, 1f. (one compound sentence); 7, 65, 2; 66, 4-5; 10-11; cf. 1, 10, 6f. Questions of syntactic and stylistic interest will be discussed in chapter V. -- In oral poetry of other peoples also a thought is rarely incomplete at the end of a line which is marked by a pause for breath.].

In studying Vedic verses scholars have too often had a bias in favour of the implicit assumption that they are the natural continuation of 'original Indo-European' verses which in their opinion were characterized, like those of the ancient Greeks, by a more or less fixed arrangement of long and short syllables11 [See e.g. A. MEILLET, in JA 1897, 2, p. 300; Les origines indo-europeennes des metres grecs, Paris 1923.]. However, the main principle governing Vedic metre is isosyllabism [syllables are of equal length]; the systematic alternation of short and long, or of stressed and weak syllables is an incompletely realized secondary characteristic. Such a fixed alternation is, moreover, in all metres more rigidly determined in the latter part of the unit than in the earlier part. So there is much to say for the supposition that in the Indo-Iranian period -- as is the case in the Avesta -- the principle was the number of syllables only12 [This is not to say that this versification was 'primitive'; compare e.g. also C. M. BOWRA, Primitive song. New York 1962. p. 87; even a 'bard' in the Yugoslav tradition might not be able to tell how many syllables there are between pauses (A. B. LORD. The singer of tales, Cambridge Mass. 1960. p. 32).]. In India the quantities tended to become more and more fixed13 [H. OLDENBERG, Zur Geschichte des Sloka, NG 1909, p. 219 (= K. S. p. 1188); Zur Geschichte des Tristubh, NG 1915 (1916), p. 490 (= K. S. p. 1216); ZDMG 37, p. 54 (= K. S. p. 441).]. The 'popular' and freer anustubh of the Atharvaveda-Samhita and the grhyasutras -- in which the process of fixing the quantities is in a more rudimentary state -- may be regarded as structurally and chronologically earlier than the more strictly regulated 'hieratic' octosyllabic verses [lines that have eight syllables.]14 [BLOOMFIELD, A.V.G. B., p. 41, but see also OLDENBERG, at ZDMG 54, p. 181 (= K. S. p. 85).] of the Rgveda which however did not fail to influence, in course of time, the 'popular' form of the metre. Very often a hymn of the Rgveda consists of stanzas in the same metre throughout. A typical divergence from this rule was then already to mark the conclusion of the poem with a stanza in a different metre15 [OLDENBERG, H.R.I, p. 140. See e.g. RV. 1, 64; 82; 90; 143; 158; 2, 8; 13; 5, 55; 59; 64; 65; 6, 8; 7, 104; 8, 78 etc. The tendency to conclude a series with a longer or 'heavier' end is well known also in other arts and among other peoples. In part of the cases the two last stanzas are in a different metre: 1, 51; 141; 157; 166; 5, 44; 8, 17; 10, 9; elsewhere the last and the third last: 1, 52; 182; the last and another stanza: 1, 85; 2, 23; or the second last one: 1, 179; 4, 50; or the first: 7, 41; 44; 8, 37; 92; another stanza 5, 36; 8, 48, 96; 10, 34.]. In the Atharvaveda the metres vary in the same hymn more than is customary in the Rgveda16 [Hymns with two or more different metres are RV. 1, 54; 84; 88; 89: 120; 3, 53; 4, 7; 7, 55; 8, 26; 30 etc. In many hymns two metres are used alternately: 1, 36; 39; 7. 74; 81; 8, 20; 27 etc. The hymns 5, 53 and 8, 46 are examples of a considerable degree of variation.]. It has not without reason been supposed that this variation was to a certain extent made a stylistic device17 [BLOOMFIELD, l.c. and in JAOS 17, p. 176; 21, p. 46.]. In 2, 24 the only stanza in a different metre (12) constitutes the culmination of the poet's address. In part of the cases -- especially those in which a hymn consists of two metrically different sets of stanzas18 [Cf. RV. 1, 50; 58; 2, 32; 7, 1; 34; 56; 9, 5. Cases are not lacking in which the metre changes more than once: 5, 51; 8, 89; 103, and compare 1, 91; 3, 52.] -- the alternation, or rather interruption of the continuity, may, especially when there is at the same place a break in the context or a change in the subjects dealt with19 [Cf. RV. 1, 101; 5, 27; 6, 71; 8, 42; 10, 32.], be made a serious argument in a discussion of the structure or genesis of the hymn. An unmistakable predilection for one and the same metrical form in the poems ascribed to the same poet or family of poets is indeed not absent20 [See e.g. 1, 65-70; 137-139 (with curious predilection for interrupted repetition of the type ... jatavedasam vipram na jatavedasam; cf. AiB. 5, 11, 1); 10, 1-9 (8); compare also the three hymns 7, 1; 34; 56 and see BERGAIGNE in JA 1889 (I = 8-13), p. 151.]; for instance, outside the Atri hymns of book V the anustubh hymns are very rare21 [There is, in the Veda, no narrative metre such as its successor, the epic sloka.].

In a considerable number of instances, recurrence of otherwise identical padas is accompanied by changes in the metre which are mostly effected by extensions or abbreviations22 [BLOOMFIELD, Repetitions, p. 523; BLOOMFIELD and EDGERTON. Variants, III, p. 22.]. There moreover exists a structural relationship between tristubh and jagati because in many cases lines composed in these metres are identical, except that they add or subtract a last syllable23 [BLOOMFIELD, o.c., p. 529; LANMAN, in JAOS 10, p. 535.]. The very extensive interchange between octosyllabic and long metre lines should not however tempt us to consider24 [With W. HASKELL, at PAOS 11 (1881), p. LX.] the latter to have originated from the former. The diction of the Vedic poets is so imitative and, at the same time, so free in all matters of form as to preclude, in most cases, any decision as to the chronological precedence of a definite metrical type. There is ample evidence that metre, style and contents of stanzas or groups of stanzas usually form a harmonious whole25 [See also BLOOMFIELD, A.V.G.B., p. 41.]. The comparatively rare dvipada viraj [a species of Gayatri consisting of two Padas only (12+8 or 10+10 syllables); inadequately represented in the translation by two decasyllabic iambic lines.] stanza -- two decasyllabic units which because of a rest in the middle consist of two pentads each -- is for instance very well adapted to the 'chopped' style, jumping thought and sudden transitions of the Agni hymns 1, 65-73; (1, 66, 3):

dadhara ksemam oko na ranvo

yavo na pakvo jeta jananam,

"Guarding peace and rest, pleasant like one's home

(Is) ripe like barley, victor of peoples."

The complex and emphatic phraseology of the Vayu hymn 1, 134 and its many repetitions at the ends of the successive padas are in harmony with the complicated atyasti [four Padas of seventeen syllables each.] strophes [combining two verses, viz. a Brhati (four Padas ( 8 + 8 + 12 + 8) containing 36 syllables in the stanza) or Kakup (a metre of three Padas consisting of eight, twelve, and eight syllables respectively) followed by a Satobrhati (a metre whose even Padas contain eight syllables each, and the uneven twelve: 12+8+12+8=40).] (12, 12, 8; 8, 8; 12, 8) of which it consists26 [Cf. e.g. also 1, 139; 9, 111; ARNOLD, o.c., p. 237; RENOU, E.V.P. II, p. 33; 42 etc.]:

(3) vayur yunkte rohita vayur aruna

vayu rathe ajira dhuri volhave

vahistha dhuri volhave ...

"Vayu (Wind) yokes the two chestnut horses, Wind the two tawny ones,

Vayu puts to the chariot the two agile (ones) in the yoke to draw.

The best (draught-horses,) in the yoke to draw ... "

It is perhaps no accident that the Vedic wedding hymns are prevailingly in anustubhs, the funeral stanzas in tristubhs27 [RV. 10, 85; AV. 14 or against RV. 10, 14-18; AV. 18.].

Since the verses are largely flexible and adaptable to the different themes28 [See also p. 227 etc.], a change of mood or subject is not infrequently marked by a change of metrical form. In this connection it is worth noticing that already some of the Rgvedic poets not only had a sensitiveness to the metrical structure of their productions29 [Cf. 1, 186, 4; 8, 12, 10: 10, 114, 9; 130, 3.] and were acquainted with some technical terms30 [See e.g. 1, 164. 23ff.; 2, 43, 1; 10, 14, 16. Compare also 10, 90, 9 mentioning the creation of metres and melodies.], but also attributed a wonderful creative power to them: "by means of the jagati stanza and melody the Creator placed the river in the heavens"[!!!] (1, 164, 25). They moreover made an attempt to attribute them to, or co-ordinate them with, definite deities: the viraj is said to belong to the double deity Mitra-Varuna, the tristubh to Indra, the jagati to the Visve Devas31 [RV. 10, 130, 4f.; cf. 10, 124, 9.]. These tendencies became more pronounced in the Atharvaveda -- where a larger number of technical terms appears to be known32 [AV. 8, 9, 14; 20; 10, 25; 11, 7, 8; 12, 3, 10; 19, 21 etc.] -- to be developed into a more systematic whole by the authors of the brahmanas and aranyakas33 [RENOU, in JA 250 (1962), p. 173.]. As far as they are attached to the Rgveda their works are perhaps in a third of all their speculative passages more or less concerned with the metres which are systematically co-ordinated, not only with the gods, but also with other important concepts, such as the social classes, animals, parts of the body, the provinces and quarters of the universe34 [Cf. e.g. TS. 1, 7, 5, 4; SB. 1, 2, 5, 6; 1, 3, 2, 16; 1,4, 1, 34; 1, 7, 2, 13ff.; 10, 3, 2, 1ff. For a survey see SIDDHESWAR VARMA, in Proc. 16 AJOC II, p. 10.]. The gayatri, symbolizing the social order of the brahmins, is Agni's metre35 [E.g. TS. 2, 2, 5, 5.], the tristubh, the heroic metre par excellence, is Indra's and co-ordinated with nobility36 [Haug, Ai. B. I, p. 76.]. The metres become deities themselves37 [This great significance of the metres and metrical speech in general depends largely on the number of the syllables of which they consist and the belief that objects and concepts are closely connected with another by their numerical values and proportions. Df, e.g. AiB. 1, 1, 7. (See also p. 373).], instruments of creation, and are even raised higher than the gods38 [SB. 1, 8, 2, 14; 8, 2, 2, 8; cf. 8, 2, 3, 9. Elsewhere they are associates of the gods, e.g. AiB. 4, 5, 2.].[!!!]

Why was he named HaBaKkuK? Because it is written, "At this season when the time cometh round, thou shalt be embracing (HoBeKeth) a son" (II Kings IV, 16), and he-Habakkuk-was the son of the Shunammite. He received indeed two embracings, one from his mother and one from Elisha, as it is written, "and he put his mouth upon his mouth" (Ibid. 34)' In the Book of King Solomon I have found the following: He (Elisha) traced on him the mystic appellation, consisting of seventy-two names. For the alphabetical letters that his father had at first engraved on him had flown off when the child died; but when Elisha embraced him he engraved on him anew all those letters of the seventy-two names. Now the number of those letters amounts to two hundred and sixteen, and they were all engraved by the breath of Elisha on the child so as to put again into him the breath of life through the power of the letters of the seventy-two names. And Elisha named him Habakkuk, a name of double significance, alluding in its sound to the twofold embracing, as already explained, and in its numerical value (H.B.K.V.K. =8.2.100.6.100) to two hundred and sixteen, the number of the letters of the Sacred Name. By the words his spirit was restored to him and by the letters his bodily parts were reconstituted. Therefore the child was named Habakkuk, and it was he who said: "O Lord, I have heard the report of thee, and I am afraid" (Habak. III, 2). that is to say, I have heard what happened to me, that I tasted of the other world, and am afraid....

The following is another explanation of the words: "These are the generations of heaven and earth." The expression "these are" here corresponds to the same expression in the text: "these are thy gods, O Israel" (Ex. XXXII, 4). When these shall be exterminated, it will be as if God had made heaven and earth on that day; hence it is written, "on the day that God makes heaven and earth". At that time God will reveal Himself with the Shekinah and the world will be renewed, as it is written, "for as the new earth and the new heaven, etc." (Is. LXVI, 22). At that time "the Lord shall cause to spring from the ground every pleasant tree, etc.", but before these are exterminated the rain of the Torah will not descend, and Israel, who are compared to herbs and trees, cannot shoot up, as is hinted in the words: "no shrub of the field was yet in the earth, and no herb of the field, etc." (Gen. II, 5), because "there was no man", i.e. Israel were not in the Temple, "to till the ground" with sacrifices. According to another explanation, the words "no shrub of the field was yet in the earth" refer to the first Messiah, and the words "no herb of the field had yet sprung up" refer to the second Messiah. Why had they not shot forth? Because Moses was not there to serve the Shekinah -- Moses, of whom it is written, "and there was no man to till the ground". This is also hinted at in the verse "the sceptre shall not depart from Judah nor the ruler's staff from between his feet", "the sceptre" referring to the Messiah of the house of Judah, and "the staff" to the Messiah of the house of Joseph. "Until Shiloh cometh": this is Moses, the numerical value of the two names Shiloh and Moses being the same. It is also possible to refer the "herbs of the field" to the righteous or to the students of the Torah ....

GET THEE FORTH. R. Simeon said: 'What is the reason that the first communion which God held with Abraham commenced with the words "Get thee forth" (lech lecha)? It is that the numerical value of the letters of the words lech lecha is a hundred, and hence they contained a hint to him that he would beget a son at the age of a hundred. See now, whatever God does upon the earth has some inner and recondite purpose....

God here blessed Abraham because he was on a par with the whole world, as it is written: "These are the generations of the heaven and the earth when they were created" (Gen. II, 4), where the term behibaream (when they were created), by a transposition of letters, appears as beabraham (in Abraham). The numerical value of the letters of yihyah (will become) is thirty, which points to the traditional dictum that the Holy One provides for the world thirty righteous men in each generation in the same manner as He did for the generation of Abraham. R. Eleazar supported this from the verse: "He was more honourable than the thirty, but he attained not to the three" (II Sam. XXIII, 23). 'The thirty', he said, 'refers to the thirty righteous whom the Holy One has provided for the world without intermission; and Benaiah the son of Jehoiada of whom it is written "He was the most honourable of the thirty" was one of them. "But he attained not to the three": i.e. he was not equal to those other three [1] on whom the world subsists, neither being counted among them nor being deemed worthy to....

R. Hiya said: 'It has been established that when Isaac was bound on the altar he was thirty-seven years old, and immediately after Sarah died, as it is written, "And Abraham came to mourn for Sarah, and to weep for her." Whence did he come? He came from Mount Moriah, after his binding of Isaac. These thirty-seven years from Isaac's birth to the time of his being bound were thus the real life of Sarah, as indicated in the expression "and the life of Sarah was (vayihyu)", the word VYHYV having the numerical value of thirty-seven.'...

AND HE SAID: BEHOLD, I HAVE HEARD THAT THERE IS CORN IN EGYPT. GET YOU DOWN (redu) THITHER. It has already been pointed out that the numerical value of the term redu (RDV =210) amounts to the number of years Israel was in Egypt....

AND HE SAID: I AM GOD, THE GOD OF THY FATHER ... I WILL GO DOWN WITH THEE INTO EGYPT. This is an indication that the Shekinah accompanied him into exile; and wherever Israel were exiled the Shekinah followed them also into exile. Observe that Joseph sent his father six wagons, [3] an allusion to which is found in the "six covered wagons" presented by the princes to Moses (Num. VII, 3). According to another view, the number was sixty; but the two views are not contradictory. For, indeed, it is first written: "in the wagons which Joseph sent" (Gen. XLV, 27), and afterwards, "which Pharaoh sent" (Ibid. XLVI, 5), so that the truth is that those which Joseph sent were of the proper number, which had a recondite significance, but the larger number which Pharaoh sent had no such numerical symbolism...

An allusion to the "mighty hand" with which God smote the Egyptians, the word "lad having the same numerical value as yad (hand)....

Therefore it has been said that man should always imagine that the fate of the whole world depends upon him. Now he who emanates from the side of Michael is called "firstborn". Michael's grade is white silver, and therefore the redemption of the firstborn is silver: five sel 'as, according to the numerical value of the letter he in Abraham. Should such a man be successful in the study of the Torah, then a letter yod is added to him, which symbolizes holiness: for with the numerical value of yod -- namely ten -- the firstborn of cattle had to be redeemed. And when a man shall have reached this degree of holiness, then the words "Israel is holy to the Lord" (Jer. II, 3) can indeed be applied to him....

But now let us return to our former subject, namely to the supernal garment which the Holy One spreads over the soul as an armour of protection so that she should not be delivered to a "strange nation". "And if he hath betrothed her unto his son, he shall act towards her according to the rights of daughters." 'Associates,' said the old man, 'When ye shall draw nigh unto that rock upon which the whole world is sustained (R. Simeon), then shall ye tell him to remember the day of snow whereon beans were sown of fifty-two kinds and colours, [Alluding to a discussion on the word be" (understanding), the numerical value of which is fifty-two.] and having recalled that day to his mind, recall also the fact that on it we read the above verse: which, when ye have awakened in him the memory thereof, he will then unravel for you himself.'...

Therefore we proclaim loudly: "Hear, O Israel; prepare thyself, for thy Husband has come to receive thee." And also we say: "The Lord our God, the Lord is one", which signifies that the two are united as one, in a perfect and glorious union, without any flaw of separation to mar it. As soon as the Israelites say, "The Lord is One", to arouse the six aspects, these six unite each with each and ascend in one ardour of love and desire. The symbol of this is the letter Vau (because its numerical value is six) when it stands alone without being joined to any other letter. Then the Matrona makes herself ready with joy, and adorns herself with delight, and Her attendants accompany Her, and in hushed silence She encounters her Spouse; and Her handmaids proclaim, "Blessed be the Name of the Glory of His Kingdom for ever and ever."...

'The Sabbath service continues with the prayer: "The soul of all living shall bless thy name, O Lord our God." The Companions have made some true observations on this prayer. But the real truth is that on Sabbath it is incumbent on us to mention that soul which emanates from "the Life of Worlds" (Yesod). And since this soul belongs to Him from whom all blessings proceed and in whom they are present, who wills to water and to bless that which is below, she is given permission to bless this Place. Thus the souls which fly forth from this "Living One" on the entrance of Sabbath do actually bless that Place in order to communicate blessings to the world below which is called the "Lower Name" (Malkuth). At the same time, the region whence those souls emanate blesses the Name from above, and so it receives blessings from below and from above, and is completed in all aspects. During other days she receives blessings from those souls which bless her from below; but on the Sabbath she receives blessings from those supernal souls which bless her with forty-five words according to the numerical value of the word Mah (What?) From the words "the soul of all living" to "the God of the first and last ages" there are forty-five words; from the words "were our mouths filled with song as the sea" to the words "and with us" are very nearly fifty words, corresponding to the Mi (numerical value = fifty). From here on follow other praises which resolve themselves in the number one hundred, the completion of all (to "the great God") and form one chariot. Thus this hymn of praise and all the words contained in it are numerical symbols of the perfection of the Sabbath, and the perfection attained through it, according to the Divine purpose. Blessed is that people that has learnt how to conduct a service of praise in well-pleasing fashion!...

Then began he to expound the words, "The commandment is a lamp." 'This', he said, 'refers to the Mishnah in the same way as the "Torah and the commandment" (Ex. XXIV, 12) mean the Written and the Oral Law respectively. And why is the Mishnah called a "lamp"? Because when she receives the two hundred and forty-eight organs from the Two Arms, she opens her two arms in order to gather them into her embrace, and so her two arms encompass them and the whole is called "lamp". "The Torah is a light" which kindles that lamp from the side of primordial light, which is of the Right Hand, because the Torah was given from the Right Hand (Deut. XXXIII, 2), although the Left was included in it to attain perfect harmony. This light is included in the two hundred and seven worlds which are concealed in the region of that light, and is spread throughout all of them. These worlds are under the hidden supernal Throne. There are three hundred and ten of them: two hundred and seven belong to the Right Hand and one hundred and three to the Left Hand. These are the worlds which are always prepared by the Holy One for the righteous, and from them spread treasures of precious things, which are stored away for the delight of the righteous in the world to come. Concerning them it is written: "That I may cause those that love me to inherit substance, and I will fill their treasures" (Prov. VIII, 21). "Eye hath not seen ... what he shall do to those that wait for him" (Isa. LXIV, 3). Yesh, substance, indicates the three hundred and ten worlds (numerical value of Yesh) which are stored away under the world to come. The two hundred and seven (numerical value of 'or, light), which are of the Right Hand, are called "the primordial light", as the Left is also called "light", but not "primordial". The primordial light is destined to produce issue for the world to come. And not only in the world to come, but even now every day; for this world would not be able to exist at all if it were not for this light, as it is written, "For I have said, Mercy shall be built up for ever" (Ps. LXXXIX, 3). It was this light that the Holy One sowed in the Garden of Eden, and through the agency of the Righteous, who is the Gardener of the Garden, He set it in rows; and He took it and sowed it as the seed of truth in rows in the Garden, where it grew, multiplied, and brought forth fruit which has nourished the world, as it is written: "A light sown to the righteous" (Ps. XCVII, 11)....

THE HOOKS OF THE PILLARS AND THEIR FILLETS SHALL BE OF SILVER. Said R. Isaac: 'I presume that the "hooks of the pillars" symbolize all those who are attached to the supernal unifying pillars, [58] and that all those who are below depend on them. What is the significance of the word vavim (hooks; also the letter vau, the numerical value of which is six)? Six within six (vv), all united and nourished by the Spine which is set over them. And we have learnt in the Book of the Hidden Mystery (Sifra di-zeniutha) this dictum: "Hooks above, hooks below (six above, six below), all comprehended in one meaning and one name, having one and the same significance."...

'AND HE MADE IT A MOLTEN CALF. We are told that it weighed one hundred and twenty-five hundredweight (this figure being the numerical equivalent of the word massekah, "molten"); how, then, could he have taken them all from "their hands"? Could such a heavy weight possibly be lifted and held by human hands? The fact is, however, that they held in their hands only so much as filled them, and this portion represented the whole. It is written: "And when Aaron saw it, he built an altar before it"....

Now the injunction "to fear the Name" is accomplished by means of the hymns and songs that King David chanted, and of the sacrifices ordained by the Torah. For it behoves man to be filled thereby with fear of his Master, for those hymns belong to a region called "Fear" (yir'ah), and all the Hallelujahs are emblematic of the fear of the Holy One, [Because the word Hallelujah has the same numerical value as Elohim, signifying the attribute of Justice.] blessed be He; it thus behoves man to attune his mind to a spirit of awe in the recital of those hymns....

R. Eleazar then continued: 'It is written, "And he brought me thither, and behold, there was a man, whose appearance was like the appearance of brass, with a line of flax in his hand, and a measuring reed; and he stood in the gate" (Ezek. XL, 3). Ezekiel saw in this prophetical vision a "man", but not "a man clothed in linen" (Dan. X, 5). For it is only when the angel is on an errand of severity that he is called "a man clothed in linen". Otherwise, he assumes various guises, appears in various attire conformably to the message he bears at the time being. Now, in the present vision "his appearance was like the appearance of brass", that is, he was clothed in the raiment formed of the "mountains of brass", and the "measuring reed" that he had in his hand was not the "Obscure Lamp" of the hidden and treasured-up light, but it was formed out of a solidified part, as it were, of the residue of light left by the "Obscure Lamp", what time that light mounted up to the heights and became engraven within the scintillating and undisclosed brightness. The "measuring reed", therefore, is used for measuring the dimensions of the lower sphere. Now, there is a "measuring reed" and a "measuring line". All the measurements of Ezekiel were by the measuring reed, whereas in the work of the Tabernacle all was measured by the measuring line. This is also used for the measuring of the dimensions of this world after the pattern of the "cord" (employed in Ezekiel's Temple), inasmuch as in the process of its extension a knot was formed at every cubit length, which length became the standard measure for the purpose, called ammah (cubit). That "measuring line" thus bears the name of "cubit"; and that explains the wording, "The length of each curtain was eight and twenty by the cubit (ba-amah), and the breadth of each curtain four by the cubit" (Ex. XXXVI, 9), the singular, " cubit", pointing to the fact that it was the cubit which measured on every side. Now this was a projection from the Supernal Lamp, the lower measurement being the counterpart of the higher. The miniature lower measurement embraces a thousand and five hundred facets, each facet expanding into twelve thousand cubits. Thus one cubit moved along, growing into a "measuring line", each cubit in its turn being newly revealed; and so it resulted in a length of eight-and-twenty "by the cubit" and a breadth of four "by the cubit". Hence the one cubit covered thirty-two spaces, symbolic of the thirty-two "Paths of Wisdom" that emanate from the supernal regions. Now the length (of the curtains) was formed into four sections of seven cubits each, the number seven expressing here the central mystical idea; similarly the thirty-two Paths are embraced within the seven, in their mystical symbolism of the Divine Name. So far in regard to this measurement, which was of a higher degree of holiness; for, indeed, there was another measured substance that was designed to be a covering to this, the external comprising the number thirty-four; whilst the internal was of the number thirty-two, and, moreover, being of a higher degree of holiness, it contained the sacred colours enumerated in the passage, "of fine twined linen, and blue, and purple, and scarlet". The same lesson is indicated in the words. "I went down into the garden of nuts" (8.S. VI, 11). For, as the nut has a shell surrounding and protecting the kernel inside, so it is with everything sacred: the sacred principle occupies the interior, whilst the "other side" encircles it on the exterior. This is the inward meaning of "the wicked doth surround the righteous" (Habakkuk I, 4). The same is indicated in the very name EGVZ (nut). [The numerical value of EGVZ. (1+3+6+7)=17. Similarly, HT (sin) (9+8=17; and TVB (the good) (9+6+2)=17.] Observe that the exterior, the more it is enlarged the more worthless it becomes. As a mnemonic we have the sacrifices of the Feast of Tabernacles, the number of which goes on diminishing with the increase of days. We thus find the same here. Of the inner curtain it is written: "And thou shalt make the tabernacle with ten curtains" (Ex. XXVI, I); whereas for the outer ones the number was "eleven curtains" (Ibid. 7). Furthermore, of the outer curtains it says, "The length of each curtain shall be thirty cubits, and the breadth of each curtain four cubits" (Ibid. 8), the two numbers amounting together to thirty-four, a number symbolic of the lowest depth of poverty; [Since 34 is the numerical value of DaL (D=4, L=30), signifying the lowest extreme of poverty.] whereas the corresponding number in the ten curtains was thirty-two, a smaller number, but symbolizing the sublime mystery of the Faith, or the Divine Name. The lower is thus the higher, and the higher the lower. The former constitutes the interior, the latter the exterior. Now the same "measuring-line" went on expanding and thus measured the boards, concerning which it is written: "And he made the boards for the tabernacle of acacia-wood, standing up" (Ibid. XXXVI, 20). These symbolized the Seraphim, as indicated by the description "standing up", which is paralleled in "Seraphim were standing up" (Isa. VI, 2). Now, here it is written, "Ten cubits shall be the length of a board" (Ex. XXVI, 16), and not "ten by the cubit". This is because the boards represented the three triads with a single one hovering high above them. The number eleven and a half has its recondite significance in that the boards symbolized a striving upwards, but not yet reaching to the degree of the Ophanim, [33] the half being expressive of incompleteness. This concerns the mystery of the Holy Chariot, for the twenty boards divide themselves into ten on this side and ten on the other, denoting a reaching out to the height of the sublime Seraphim. Then there is a further ascent in the holy region, denoted by the "middle bar" (Ibid. XXVI, 28). There is also an inward significance in the twenty boards in that they embrace the number 230. [i.e. Twenty times the length of each plus twenty times the breadth of each: (20 x 10) + (20x 1-1/2) = 230. The number 230 is the numerical value of certain sacred names.] The value of each prescribed measure has here its proper meaning. The curtains of the Tabernacle mentioned before stand for sublime mysteries, namely, the mystery of heaven, regarding which Scripture says: "Who stretchest out the heavens like a curtain" (Ps. CIV, 2). Now, of the two sets of curtains, the one expresses one aspect of the mystery whilst the other expresses another aspect of the same mystery. The whole is designed to teach us Wisdom in all its aspects and all its manifestations; and so that man may discern between good and evil, between what Wisdom teaches and what it rejects. The mystery of the basic measurement, as elsewhere laid down, embraces various objects. The Ark in its dimensions falls within the same recondite principle, in respect of what it received and what it possesses of its own. We thus read: "two cubits and a half was the length of it" (Ex. XXXVII, 1). The one cubit on either side tells us about the Ark being the recipient from this side and from that side; whilst the half cubit in the centre represents what it had possessed of its own; and the same is indicated by the cubit and a half of its breadth and a cubit and a half of its height: each cubit speaks of what accrued to it, and each half of what is possessed already. For there must needs be something for something else to rest on, and hence the existing half in every account. There is a further recondite significance in that the Ark was inlaid with gold inside and outside so as to have its dimensions formed after the archetypal plan. The table was similarly measured by this archetypal scale. The dimensions of the Ark, however, were not used elsewhere, for reasons revealed to the wise. Similarly, all the other works of the Tabernacle were measured by the same cubit, with the exception of the breastplate, which was measured by the span. Now observe this. The tunic embraced the mystery of the "six" (shesh) in that it symbolized the vesture designed for the setting right and investiture of all that comes within the "six" (directions of the world). So far the recondite significance of the "measuring-line". In the vision of Ezekiel, however, we find instead the "measuring-reed", for the reason that the House which he beheld was destined to remain forever in its place with the same walls, the same lines, the same entrances, the same doors, every part in accordance with prescribed measure. But in regard to the time to come, Scripture says: "And the side-chambers were broader as they wound higher and higher" (Ezek. XLI, 7). For immediately the building will be begun that "measuring-reed" will mount higher and higher in the length and in the breadth, so that the House will be extended on all sides, and no malign influence shall ever light on it. For at that time Severity will no more be found in the world; hence everything will remain firmly and immovably established, as Scripture says, "and [they will] be disquieted no more; neither shall the children of wickedness afflict them any more", etc. (2 Sam. VII, 10). And observe that all these measurements prescribed for this world had for their object the establishment of this world after the pattern of the upper world, so that the two should be knit together into one mystery. At the destined time, when the Holy One, blessed be He, will bestir Himself to renew the world, all the world will be found to express one mystery, and the glory of the Almighty will then be over all, in fulfilment of the verse, "In that day shall the Lord be one, and his name one" (Zech. XIV, 9).'...

It is for this reason that in the command it says simply "saying" (amor), instead of the definite form "say" (imru), this being a reference to the hidden letters within the words of blessing. Again, the word AMoR has in its letters the numerical value of two hundred and forty-eight less one, equal to the number of the bodily members of man, excepting the one member on which all the rest depend. All these members thus receive the priestly blessing as expressed in the three verses.'...

He who constantly occupies himself with the Torah is compared by the Psalmist to "a tree planted by streams of water" (Ps. I, 3). Just as a tree has roots, bark, sap, branches, leaves, flowers and fruit, seven kinds in all, so the Torah has the literal meaning, the homiletical meaning, the mystery of wisdom, numerical values, hidden mysteries, still deeper mysteries, and the laws of fit and unfit, forbidden and permitted, and clean and unclean. From this point branches spread out in all directions, and to one who knows it in this way it is indeed like a tree, and if not he is not truly wise.

-- The Zohar, translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon