Part 2 of 4

In the Cshetra-samasa the Carna-phulli [Karnaphuli/ Karnafuli/ Khawthlanguipui: Wiki] or Chatganh [Chittagong: Wiki] river, is said to come from the Jayadri or mountains of victory, and the Nabhi or Naf [Naf: Wiki] river from the Suvarda, or golden mountains; but these are portions only of the above range.

The mountains, as well as the country to the eastward of Trai-pura, are often called Reang by the natives. When we read in Major Dow’s history of Hindoostan that Sultan Sujah fled from Dhacca to Aracan through the almost impervious forests and mountains of Rangamati, it is a mistake, and it should be the forests and mountains of Reang. It is not likely that that unfortunate prince should fly from Dhacca to Rangamati on the borders of Asama, a great way towards the north; but it is more natural to suppose that he darted at once into the wilds of Trai-pura and Reang.

Ptolemy has bestowed the name of Maiandrus on this range, but which is now unknown.

It is probably derived from Mayun, a tribe between Chatganh, and Aracan* [Asiatick Researches, Vol. 6th, p. 228.]

according to Dr. Buchanan. In this case Mayunadri signifies the Mayun mountains, and the Peguers are also called Moan.† [Asiatick Researches, Vol. 5th, p. 225.]

By a strange fatality, the northern extremity of mount Maiandrus in Ptolemy's maps is brought close to the town of Alosanga, now Ellasing on the Lojung river, to the N.W. of Dhacca. This mistake is entirely owing to his tables of longitude and latitude, which were originally erroneous, and probably have been made worse and worse by transcribers: but this may be easily rectified, by adverting to the interesting particulars, which he mentions concerning mount Maiandrus. In the upper parts of it, says he, are the Tilaidai, or the inhabitants of the Tiladri or Tila mountains mentioned before; these are also called Basadoe.

In the Vamana-purana, section of the earth, the Bhasada tribes are mentioned, as living in the easternmost parts of India.

Ptolemy says that the Basadoes had a short nose as if clipped, and were very hairy, with a broad chest, and a broad forehead. They were of a white colour, and I suppose like that of the Peguers, called by Persian writers, a wheat colour, and in Sanscrit Capisa.

On one side of mount Maiandrus,

according to our author[???}, are the Nanga-logoe, which, he says, signifies naked people, and this is to this day the true meaning of Nanga-loga in Hindi: their country is repeatedly called Nagna-desa, or

country of the naked in the Puranas, and they call themselves Nanctas or the naked, but this word they generally pronounce Lancta.* [Asiatick Researches, Vol. 7th, p. 183.] They are called also Cuci, and

in the Cshetra-samasa it is said, that the original name is Cemu, and Cemuca, which are pronounced in the dialect of that country Ceu, Ceuca or Ceuci; and Portuguese writers mention the country of Cu, to the eastward of Bengal.

The Vindhyan mountains are in general covered with forests

called in Sanscrit Aranya, or Atavi, and this last implies an impervious wood, or nearly so.

The Vindhyatavis are often mentioned in the Puranas, and poetical works. They are divided into forest-cantons, mentioned in the lists of countries

in the Puranas; and in geographical works among these forest-cantons, ten are of more renown than the others: these are to the east of the river Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], and are

called in the above lists Dasarna, and in geographical tracts Dasaranya, or the ten forests, and in every one of them is a stronghold, or fort Rina, and Dasarna signifies the ten forts. Another name for these forts is Uttamarna, which implies their pre-eminence, and superiority of power above the others.

These ten strongholds are probably the Dasapur, or decapolis of the last section but one of the Padma-purana, and of Cosas[???] also. There resided ten chiefs, who availing themselves of the supineness of their neighbours below, became hill robbers, and obtained at various periods much might and honor.

They were like the savage tribes of Rajamehat, only they acted upon a larger, and of course upon a more honorable scale.[???!!!]These forests are in general called Jhati-chanda, always pronounced Jhari-chand in the spoken dialects, which signifies a country abounding with Jhari, or places overgrown with thickets and underwood. However there are many extensive forests of large and tall trees of various sorts, but under these there is no grass, and very seldom any underwood: therefore the copses are most valuable, being fit for the grazing of cattle.

These ten cantons included all the woods, hills and wilds of south Bahar, with the two districts of Surugunja, and Gangapur in the south. We have also the Dwadasaranya, or twelve forest-cantons, including the ten before mentioned with the addition of Bandela-chand and Baghela-chand. Another name for such woods and thickets is Jhanci and Jhancar; which the natives of these forests generally pronounce Dangi and Dangar,

according to the Cshetra-samasa, and to the natives also, who call themselves Dangayas from Bandela-chand, all the way to the bay of Bengal, and their country Dangaya. The other Hindus however call the whole Jhar-chand, and

it is noticed in Dow's history of India, and in that of Bengal by Major Stewart,* [History of Bengal, p. 123, 265. 371.] and also either by Tavernier or Bernier, but supposed by them to be a town in the vicinity of Berhampur, instead of an extensive forest. They call it Geharcunda, and suppose it to mean a cold place. In Bengal they call it often Jangal-teri and

in the Cshetra-samasa, Jangal-cshetra and Jar-chandi, all implying the woody country.

In the Company’s Registers, they are called the Junglemehals or forest-cantons.

According to Major Dow’s history, when the emperor Firose III, in the year 1358, was returning from Bengal, he passed through

the Padmavati forest, which is one of the old names of Patna, once the metropolis of that country. These forests abounded with elephants, and the emperor caught many.

For a similar reason, the mountains and forests of Jhar-chand are

called, in the Peutingerian tables, the Lymodus mountains, abounding with elephants, and placed there to the south of the Ganges.

Tabula Peutingeriana (Latin for "The Peutinger Map"), also referred to as Peutinger's Tabula or Peutinger Table, is an illustrated itinerarium (ancient Roman road map) showing the layout of the cursus publicus, the road network of the Roman Empire.

The map is a 13th-century parchment copy of a possible Roman original. It covers Europe (without the Iberian Peninsula and the British Isles), North Africa, and parts of Asia, including the Middle East, Persia, and India. According to one hypothesis, the existing map is based on a document of the 4th or 5th century that contained a copy of the world map originally prepared by Agrippa during the reign of the emperor Augustus (27 BC – AD 14). However, Emily Albu has suggested that the existing map could instead be based on an original from the Carolingian period.

Named after the 16th-century German antiquarian Konrad Peutinger, the map is now conserved at the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

-- Tabula Peutingeriana, by Wikipedia

They really were in the country of

Magadh or Magd, as generally pronounced, and which was also the name of Patna and of south Bahar. 4. He claims the capital is Palimbothra or Palibothra, and that the city exists near the confluence of the Ganga and the Eranaboas (Hiranyabahu).

But the Puranas are clear that all the 8 dynasties after the Mahabharata war had their capital at Girivraja (Rajagriha), located in the foothills of the Himalayas. There is no mention of Pataliputra in the Puranas. So, the assumption made by Sir William that Palimbothra is Pataliputra has no basis in fact and is not attested by any piece of evidence. If the Greeks could pronounce the first P in (Patali) they could certainly have pronounced the second p in Putra, instead of bastardising it as Palimbothra. Granted the Greeks were incapable of pronouncing any Indian names, but there is no reason why they should not be consistent in their phonetics.

-- Historical Dates From Puranic Sources, by Prof. Narayan Rao

Much information concerning India was derived from Arabian merchants and sailors, by whom the Greek and Roman fleets were chiefly manned. These to the names of countries prefixed the Arabic article Al, as in Al-tibet, Al-sin, &c.: thus they said Al-mogd for Magadh, Al-murica and Al-aryyaca, for Mura or Murica and Aryyaca, from which the Greeks made Limyrica and Lariaca. El-maied or Patna is placed, in the above tables, 250 Roman miles to the eastward of the confluence of the Jumna with the Ganges, and its name is written there Elymaide. These forests are called Ricshavan, or bear forests, and the inhabitants Bhallata or Bhallatha, bear hunters or bear killers.* [

Maha-bharat, Bhishma, section and commentary.] These are the Phyllitoe of Ptolemy, and the Bulloits of Captain Robert Covert. There were also the Dryllo-phyllitoe, probably from some place called Derowly: the Condali now the Gonds (as Bengala, from Banga) were part of the Phyllitoe. This shews that these bear hunters were spread over a most extensive region.

As these extensive forests abound with snakes, the country is called in Sanscrit, Ahi-cshetra, or snake country, and Ahi-chhatra, from the snakes spreading there their umbrellas or hoods. In the spoken dialects, they say Aic-het and Aic-shet. The country and mountains of Aic-shet are well known all over the peninsula,

according to Pr. F. Buchanan in his account of Mysore, Ptolemy gives to the mountains of south Bahar and in the western parts of Bengal the name of Uxentus, obviously from Aic-shet. In the southern parts, or in Burra-nagpur, and adjacent countries, he calls them Adisathrus from Ahichhatra. The country about the Vindhyan hills, from Rajamehal to Chunar, is divided into Antara-giri, or within the hills, and Bahira-giri, or without the hills, and this last is applied to the country to the south of Patna along the Ganges.

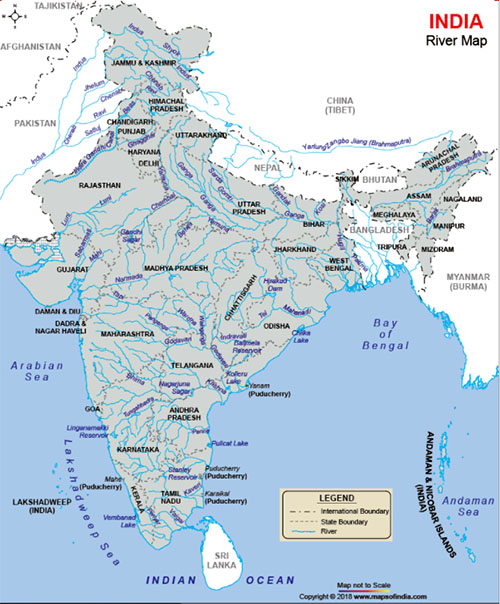

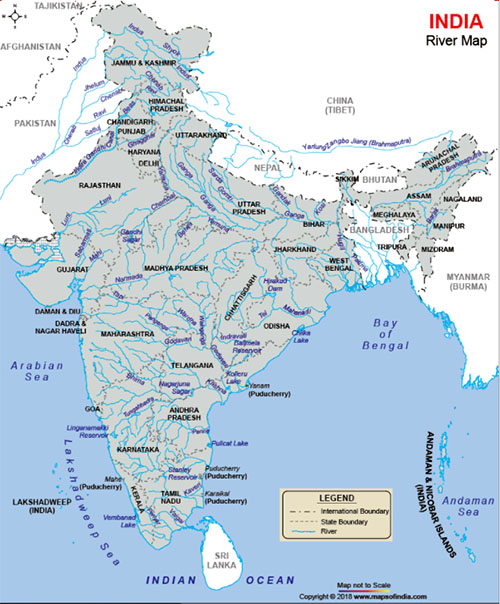

India River Map

India River Map

Now let us pass to the rivers, and l shall describe first, those on the right of the Ganges, then the rivers on the left of it; and I shall conclude this section with an account of the Ganges itself. This I believe is the best way, as it will obviate many repetitions.

The first river of note below Hurdwar, and on the right side of the Ganges, is the Calindi, or Calini, for both are used indifferently by the natives, and which falls into the Ganges near Canoge. She is considered as the younger sister of the Yamuna: hence it is called the lesser Yamuna, or Calindi.

This accounts for Ptolemy mistaking it for the elder or greater Yamuna, and making but one river of the two; Don Joan de Barros did the same when he says that Canoge was at the confluence of the Jamuna with the Ganges. Mr. D'Anville, better informed, removed the greater Jumna to its proper place; but carried along with it Canoge, which accordingly he placed near Allahabad, at least in his first maps. The royal road from the Indus[???] to Palibothra crossed this river at a place called Calini-pacsha [Kalinipaxa], according to Megasthenes, and now probably Khoda-gunge; Calini-pacsha in Sanscrit signifies a place near the Calini.

The next is the blue Yamuna [Yamuna/Jamuna: Wiki] or Calindi [Kalindi/"Yamuna {Kalindi} is one of the ashtabharya {8 wives} Lord Krishna": Wiki], the daughter of the sun, the sister of the last Manu, and also of Yama or Samana, our Pluto or Summanus.

Her relationship with the lesser Calindi, or Calini, is not noticed by the Pauranics, though otherwise well known. In the spoken dialects it is called Jamuna, Jumna, and Jubuna particularly in Bengal.

It is called Diamuna by Ptolemy, Jomanes by Pliny, and Jobares by Arrian, probably for Jobanes or Jubuna. It is called Calindi because it has its source in the hilly country of Calinda,

called Culinda in the Geographical Commentaries on the Maha-bharata.[???] It is the Culindrine of Ptolemy from Culindan, a derivative from Culinda.

The confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna at Prayaga is called Triveni by the Pauranics; because three rivers are supposed to meet there; but the third is by no means obvious to the sight. It is the famous Sarasvati, which comes out of the hills to the west of the Yamuna, passes close to Thaneser, loses itself in the great sandy desert, and re-appears at Prayag, humbly oozing from under one of the towers of the fort, as if ashamed of herself. Indeed she may blush at her own imprudence: for she is the goddess of learning and knowledge, and was then coming down the country with a book in her hand, when she entered the sandy desart, and unexpectedly was assailed by numerous demons, with frightful countenances, making a dreadful noise. Ashamed of her own want of foresight she sank into the ground, and re-appeared at Prayaga or Allahabad, for as justly observed, learning alone is insufficient. Formerly she was in the region of the height, in the thirteenth æon.... It came to pass, when Pistis Sophia was in the thirteenth æon, in the region of all her brethren the invisibles, that is the four-and-twenty emanations of the great Invisible, -- it came to pass then by command of the First Mystery that Pistis Sophia gazed into the height. She saw the light of the veil of the Treasury of the Light, and she longed to reach to that region, and she could not reach to that region. But she ceased to perform the mystery of the thirteenth æon, and sang praises to the light of the height, which she had seen in the light of the veil of the Treasury of the Light.

It came to pass then, when she sang praises to the region of the height, that all the rulers in the twelve æons, who are below, hated her, because she had ceased from their mysteries, and because she had desired to go into the height and be above them all. For this cause then they were enraged against her and hated her, [as did] the great triple-powered Self-willed, that is the third triple-power, who is in the thirteenth æon, he who had become disobedient, in as much as he had not emanated the whole purification of his power in him, and had not given the purification of his light at the time when the rulers gave their purification, in that he desired to rule over the whole thirteenth æon and those who are below it.... [the great triple-powered Self-willed] emanated out of himself a great lion-faced power, and out of his matter in him he emanated a host of other very violent material emanations, and sent them into the regions below, to the parts of the chaos, in order that they might there lie in wait for Pistis Sophia and take away her power out of her.

-- Pistis Sophia: A Gnostic Miscellany, Translated by G.R.S. Mead, 1921

These three rivers flow then together, as far as the southern Triveni in Bengal, forming the Triveni, or the three plaited locks: for their waters do not mix, but keep distinct all the way. The waters of the Yamuna are blue, those of the Sarasvati white, and the Ganges is of a muddy yellowish colour. These appearances are owing partly to the nature of the soil below, and above to the reflexion of light from the clouds.

The Tamasa, or dark river, from its being skirted, at least formerly, with gloomy forests, is called Tonsa or Tonso in the spoken dialects and by Ptolemy Touso or Tousoa. It is not to be confounded with the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki]; for

the Touso, according to him falls into the Ganges, above Cindia now Canti or Mirzapur. It is occasionally

called Parnasa, as in the Vayu and* [Section of the earth.] Matsya-puranas; and at its confluence with the Ganges, there is a very ancient place, and fort called to this day Parnasa.

The next river is the hateful Carmmanasa, so called, because, by the contact alone of its waters, we lose at once the fruit of all our good works. Its source is in that part of the Vindhya hills

called in the Puranas Vindhya-maulica,

which implies the heads, peaks or summits of the original mountains of Vindhya.

This mountain presumed once to rear his head above that of Himalaya, and thus consigned it and the intermediate country to total darkness. One day Vindhya, perceiving the sage Agastya his spiritual guide, prostrated himself to the ground before him as usual, when the sage as a punishment for his insolence, ordered him to remain in that posture. We had such mountains formerly in the west, which kept the greatest part of Europe in constant darkness, and which must have met with a similar fate, though not recorded.

All the ground he covers with his huge frame is denominated Mauli, or the heads or peaks of Vindhya, and is declared to be the original Vindhya, which gives its name to the whole range, from sea to sea,

and is supposed to extend from the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki] to the Tonsa. As the Carmmanasa comes from the country of Mauli, there is then a strong presumption, that it is the river Omalis of Megasthenes: thus the great river, which he calls Commenasis, is the Sarayu, and is so called, because it comes from the country of Comanh, or Almora. The river Cacuthis of the same author is the Puna-puna, [Punpun: Wiki], and is so called because it flows through the country of Cicata. It is also called Magadhi by the Pauranics, for a similar reason. In this manner the Yamuna is also called Calindi, because it comes from the hilly country of Calinda, as I observed before.The waters of the river Mauli were originally as pure, and beneficial to mankind, as those of any river in the country. However they were long after infected and spoiled through a most strange and unheard of circumstance, in consequence of which its present name was bestowed upon it.

Tri-sancu was a famous and powerful king, who lived at a very early period, and through religious austerities, and spells, presumed to ascend to heaven with his family. The gods, enraged at his insolence, opposed him, and he remains suspended half way with his head downwards. From his mouth issues a bloody saliva, of a most baneful nature. It falls on Vindhya, and gives to these mountains a reddish hue: hence they are called Rohita or Lohita, the red and bloody hills in the vicinity of Rotas. It is unnecessary to remark, that this infectious saliva, mixing with the waters of the river Mauli, would naturally infect, and render them most inimical to religious purposes. This legend is well known; but the best account I ever saw is in the Maha-Ramayana, in a dialogue between Agastya and Hanuman.

The next is

the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], or red river:

in the Puranas it is constantly called Sona, and I believe never otherwise.

In the Amara cosa, and other tracts, I am told, it is called Hiranya-bahu, implying the golden arm, or branch of a river, or the golden canal or channel. These expressions imply an arm or branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], which really forms two branches before it falls into the Ganges. The easternmost, through the accumulation of sand, is now nearly filled up, and probably will soon disappear.

The epithet of golden does by no means imply that gold was found in its sands. It was so called, probably, on account of the influx of gold and wealth arising from the extensive trade carried on through it; for it was certainly a place of shelter for all the large trading boats during the stormy weather and the rainy season.

In the extracts from Megasthenes by Pliny and Arrian, the Sonus and Erannoboas appear either as two distinct rivers, or as two arms of the same river. Be this as it may, Arrian says that the Erannoboas was the third river in India, which is not true. But I suppose that Megasthenes meant only the Gangetick provinces: for he says that the Ganges was the first and largest. He mentions next the Commenasis or Sarayu, from the country of Commanh, as a very large river. The third large river is then the Erannoboas or river Sona[???].

Ptolemy, finding himself peculiarly embarrassed with regard to this river, and the metropolis of India situated on its banks, thought proper to suppress it entirely. Others have done the same under similar distressful circumstances. It is however well known to this day, under the denomination of Hiranya-baha, even to every school boy, in the Gangetick provinces, and in them there is no other river of that name.[???!!!] The origin of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], and of the Narmada, is thus described by F. Tieffenthatler, on the authority of an English officer, who surveyed it about the year 1771* [Beschreibung von Hindoostan, &c. p. 298. Some account of it is given also, from native authorities by Captain Blunt, Asiatick Researches, Vol. 7th p. 100.]

according to an English Engineer, who went from Allahabad to the source of the Narmada, there are three rivers, which have their origin from a pool eight yards long and six broad, and surrounded by a border of brick. This pool is in the middle of the village of Amarcantaca. Above it is a rising ground about fifty yards high, on which Brahmens have built houses. The Narmada flows from the said pool, a mile and half towards the east, then falls with violence down a declivity of about twenty-six yards, and then runs with velocity towards a village called Capildara, and from this place through an extensive forest, and then turning towards the west it goes to Garamandel, and thence into the sea. In coming out of the above pool it is one yard broad.

The Sone makes its first appearance about half a mile from the pool, and then runs through a very narrow bed, down a declivity of about twenty-five yards. Five miles thence it is lost in the sands; then collecting itself again into one body, it becomes a considerable stream, and goes to Rhotas. The Juhala (Johila) is first seen about three miles from the pool, and is but an insignificant stream.

Tieffenthaler has omitted the name of the officer, but it was William Bruce, a Major in the Company’s service, and mentioned by Major Rennel.† [See Memoir of a map, &c. p. 234.]

The next river is the Puna-puna, [Punpun: Wiki], which signifies again and again, in a mystical sense[???]; for it removes sins again and again. It is a most holy stream, and is called also Magadha, because it flows through the country of Magadha or Cicata. Hence this river might be called also Cicati, and it is the Cacuthis of Megasthenes. Then comes the Phalgu, the Fulgo of the maps. I thought formerly, that it was the anonymous river of

Ptolemy, which he derives from the mountainous regions of Uxentos, in Hindi, Aicshet, from the Sanscrit Ahicshetra.

Our author has pretty well pointed out its confluence with the Ganges near Mudgir, where it receives another river from the south, called the Kewle in the maps, and

which is really the anonymous stream of that author, as it appears from several towns on its banks:

but Ptolemy has lengthened its course beyond measure; as I shall show hereafter.

Let us now proceed to the Sulacshni, or Chandravati,

according to the Cshetra-samasa. It is now called the river Chandan, because it flows through the Van or groves of Chandra, in the spoken dialects Chandwan, or Chandan.

In the maps it is called Goga,

which should be written Cauca, because according to the above tract, it falls into the Ganges, at a place called Cucu, and in a derivative form Caucava, Caucwa, or Cauca. It flows a little to the eastward of Bhagalpur:

but the place, originally so called, has been long ago swallowed up by the Ganges, along with the town of Bali-gram. In the Jina-vilas[???], it is called Aranya-baha[!!!], or the torrent from the wilderness, being really nothing more.

The next is the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], or red river: in the Puranas it is constantly called Sona, and I believe never otherwise. In the Amara cosa, and other tracts, I am told, it is called Hiranya-bahu, implying the golden arm, or branch of a river, or the golden canal or channel. These expressions imply an arm or branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], which really forms two branches before it falls into the Ganges.

The other rivers, as far as Tamlook, are from the Cshetra-samasa. The Rada, now the Bansli [Bansloi: Wiki], falls into the Ganges near Jungypur [Jangipur: Wiki].

I believe it should be written Radha, because it flows through the country of that name.

The Dwaraca [Dwarka: Wiki] is next: then, the Mayuracshi [Mayurakshi: Wiki], or with

the eyes of a Mayura, or peacock [Peacock eyes: Wiki]; this is the river More. To the N.E. of Jemuyacandi are the following small rivers, the Gocarni, and beyond this the Chila, and the Grivamotica,

in the spoken dialects Garmora. Their path towards the Ganges is winding and intricate.

The next river is the Bacreswari [Bakreshwar: Wiki], which comes from the hot wells of Bacreswara-mahadeva, or

with the crooked Linga.

These hot wells are of course a most famous and holy place of worship. It falls into the Ganges above Catwa, and it is

called in the maps Babla.

The Aji, or resplendent river, is the next: its name at full length is Ajavati or Ajamati, full of resplendence.

The Ajmati, as it is pronounced, is the Amystis of Megasthenes, instead of Asmytis. It fell into the Ganges, according to Arrian, near a town called Catadupa,

the present, and real name of which is Cata-dwipa; but it is more generally called Catwa. The Aji is called also Ajaya, Ajayi and Ajasa, in the Galava-Tantra.[???] As Ajaya may be supposed to signify invincible, it is declared, that whatever man bathes in its waters, thereby becomes unconquerable.

The next river is the Damodara [Damodar: Wiki], one of the sacred names of Vishnu, and

according to the Cshetra-samasa, it is the Vedasmriti, or Vedavati of the Puranas. Another name for it is Devanad, especially in the upper parts of its course.

In the spoken dialects it is called Damoda or Damodi.

It is the Andomatis of Arrian, who says that it comes, as well as the Cacuthis, now the Puna-puna [Punpun: Wiki], from the country of the Mandiadini, in Sanscrit Manda-bhagya or Manda-dhanya.

The Dariceswari, or Daricesi, is called Dwaracesi

in the Gatava-Tantra.[???] It is the Dalkisor of the maps, near Bishenpur.

It is so called from Dariceswara-mahadeva.[???] Then comes the Silavati, Sailavati, or Sailamati* [In Sanscrit the words va, vati, or mati, man, and mant originally signify, in composition, likeness; but in many instances they imply fullness, abundance. In Latin we knew Farcimen, farcimentum likewise, &c.]

called simply Sailaya by the natives, and Selai in the maps. It is the subject of several pretty legends, and a damsel born on its banks, and called also Sailamati from that circumstance, makes a most conspicuous figure in the Vrihatcatha.

It is the Solomatis of Megasthenes. The next river is the Cansavati,

called Cansaya by the natives, and Cassai in the maps. The three last rivers joining together form the Rupa-Narayana, or with the countenance of him, whose abode is in the waters, and who is Vishnu.

Then comes the Suvarna-recha [Subarnarekha/Swarnarekha: Wiki], or Hiranya-recha, that is to say the golden streak [Subarnarekha, meaning "streak of gold" found in the riverbed: Wiki]. It is called also in the Puranas, in the list of rivers, Suctimati, flowing from the Ricsha, or bear mountains. Its name signifies abounding with shells, in Sanscrit Sucti, Sancha, or Cambu.

From Cambu, or Cambuja, in a derivative form, comes

the Cambuson mouth of Ptolemy and which, he thought, as well as many others till lately, communicated with the Ganges, of even was a branch of it.

The Suvarna-recha, it is true, does not fall into the Ganges any more than the four rivers, which I am going to mention; but they are so situated, that it is necessary to give some account of them, for the better understanding of this Geographical Essay. Of these four rivers the first is

the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], which flows by Balasore, and is not noticed, as far as I know, in the Puranas. The next is the Vaitarani, which runs by Yajapur,

the Jaugepoor of the maps. In the upper part of its course it is called Cocila, and

in the spoken dialects Coil.

There are two rivers of that name, the greater and the lesser;

this last is I believe the Salundy of the maps. The greater Vaitarani is

generally called Chittrotpala in the Puranas. The third is the Brahmani, called Sancha in the upper part of its course. This and the Vaitarani come from the district of Chuta-Nagpur.

The fourth river is the Maha-nada or Maha-nadi [Mahanadi/Hirakud Dam: Wiki], that is to say the great river.

It is mentioned in the lists of rivers in the Puranas, but otherwise it is seldom noticed. It passes by Cataca.

Ptolemy considers the Cocila and Brahmani rivers as one, which he calls Adamas, or diamond river, and

to the Maha-nadi he gives the name of Dosaron. He is however mistaken: the Maha-nadi is the diamond river, and his Dosaron consists of the united streams of the Brahmani and the Cocila, and is so called because they come from the Dasaranya, also Dasarna, or the ten forest-cantons.

He might indeed have been led into this mistake very easily, for the Brahmani and Cocila come from a diamond country in Chuta-Nagpur, and in Major Rennell’s general map of India, these diamond mines towards the source of these two rivers are mentioned, and seem to extend over a large tract of ground.

Before we pass over to the other side of the Ganges, let us consider the rivers which fall into the Yamuna. The first river is the Goghas, to be pronounced Goghus, which passes close to Amara, or Amere near Jaypur. It comes from the east, and is first noticed at a place called Ichrowle, as it passes to the north of it, at some distance. It winds then towards the S.W. and goes towards Amere and Jaypur, thence close to Bagroo, when it turns to the south, and soon after to the S.E. The village of Ichrowle, being near the Goghus, is also

called Goghus after it, or Cookus, as it is written in Arrowsmith's map: but it is considered by that famous geographer, as a different place from Ichrowle.[!!!] This river is

called Damiadee[???], by some of our writers of the seventeenth century, and is supposed by them to come from the mountainous district of Hindoon, and then to flow close to that city towards the west, and to fall into the Indus at Bacar,

according to Captain R. Covert, who was there I believe in the year 1609 or 1610. This is by no means a new idea, for

this is the river without a name mentioned by Ptolemy, who places, near its source, a town called Gagasmira, in which the names of the Goghas, and of the town of Amere, are sufficiently obvious. Some respectable travellers, who have occasionally visited that country, are of the same opinion, being deceived by seeing that river flowing towards the west a considerable way.

The town of Hindoon still exists, and the inhabitants of the adjacent country who were formerly great robbers, trusting to their fastnesses among the hills, are still so, whenever they can plunder with safety. It is

most erroneously called Hindour in Arrowsmith’s map, and I am sorry to observe that otherwise admirable work disfigured by bad orthography, the result of too much hurry and carelessness, and the errors are equally gross and numerous, and sometimes truly ludicrous. As to the Damiadee[???],* [See Andrew Brice's Dictionary ad vocem and others.] this appellation is now absolutely unknown. The first notice I had of the Goghas was from a native surveyor, whom I sent to survey the Panjab, and who accidentally passed through Jaypur, but remained there several days.

The Damiadee[???] was first noticed by the Sansons in France, but was omitted since by every geographer, I believe, such as the Sieur Robert, the famous D’Anville, &c; but

it was revived by Major Rennell, under the name of Dummody. I think its real name was Dhumyati, from a thin mist like smoke, arising from its bed. Several rivers in India are so named:

thus the Hiranya-baha, or eastern branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], is called Cujjhati, or Cuhi† [Commentary on the Geog. of the M. Bh.] from Cuha, a mist hovering occasionally over its bed. As this branch of the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki] has disappeared, or nearly so, this fog is no longer to be seen. I think, this has been also the fate of the Dhumyati, which is now absorbed by the sands. This Dhumyati, seen at Baccar by Capt. Covert, did not come from Hendown, but from some place in the desert, still unknown, but

I suspect that it is the river, without name, placed, in Arrowsmith's map, to the E. N. E. of Jaysulmere. It passes near a village called Lauty or Latyanh, which village is said to be twenty Cos to the east of Jaysulmere, by the late Major D. Falvey, who travelled twice that way, in the years 1787 and 1780: according to him there is no river, nor branch of the Indus between Jaysulmere, and Baccar. He was a well informed man, who understood the country languages, and in his route he always took particular notice of the rivers which he crossed.

The Damiadee is now called by the natives, Lohree[???] or Rohree[???], from a town of that name, near its confluence with the Indus.

I am assured that, during the rains, the backwater from the Indus runs up the dry bed of a river for a space of three days. This dry bed is supposed to have been formerly the bed of a river formed by the united streams of the rivers Caggar, and Chitangh from the plains of Curu-cshetra,

but this I think highly improbable. The next is the Charmmanwati [Charmanwati: Wiki], or abounding with hides.

It is often mentioned in the Puranas, and is called also Charmmabala, and Sivanada, in the spoken dialects Chambal and Seonad. It is sometimes represented as reddened with the bloody hides put to steep in its water.* [

In the Megha Data[???] this river is said to have originated in the blood shed by Ranti Deva at the Gomedhas, or offerings of kine.]

The hides, under the name of Chembelis, were formerly an article of trade.* [See Dictionnaire de Commerce.] The country about its source is called Charmma-dwipa, which is certainly between waters or rivers, which abound in that country.

There is a town called Sibnagara, or more generally Seonah, the town of Siva, after whom this river is denominated. The Sipra, Sipra, Cshipra, called also the Avanti river, falls into the Chambal.

The Sindhu[???] or Sind[???], is occasionally mentioned in the Puranas, as well as the little river Para, commonly called Parvati, which, after winding to the north of Narwar, falls into the Sindhu near Vijayagar. It is famous for its noisy falls, and romantic scenes on its banks, and the numerous flocks of cranes and wild geese to be seen there, particularly at Buraicha west of Narwar. The next is the little river Pauja, which falls into the Yamuna, and is

called in the spoken dialects Pauja, and in the maps Puhuj. The Vetrarati [Betwa/Shuktimati, "In Sanskrit 'Betwa" is Vetravati": Wiki], or abounding with withies [a tough, flexible branch of an osier or other willow, used for tying, binding, or basketry.], is a most sacred river. Vetra or Betra is a withy, and so is Vithr in the old Saxon. In the spoken dialects and in English, the letter R is omitted; in Hindi they say Beit and in English With or withy.

In the spoken dialects, it is called Betwa and Betwanti.

The river Dussaun, which falls into the Vetravati

is probably the Dasarna of the Pauranics. The next river is that which we call the Cane: but

its true name is Ceyan, and the author of the Cshetra-samasa says that it is the Criya, or Criyana of the Puranas, and called Ceyan in the spoken dialects. Another name for it is Crishna-ganga, which,

according to the Varaha-purana flows by Calanjara.

Let us now pass to the rivers to the north of the Ganges, or on the left of it. The first is the Saravati, or full of reeds [mythical river: D.C. Sircar, 1971]:

another name of the same import is Bana-ganga, this is used by natives: in the Maha-bharata, it is called Su-Vama, or most beautiful: its present name,

and of the same import is Rama-ganga, or Ramya-ganga.

In the Saravan, or Saraban, that is to say the thickets of reeds on its banks, Carticeya was born. This name is sometimes applied to the river itself, though improperly, and

from Saraban, Ptolemy made Sarabon and Sarabos. It is called

Sushoma, in the Bhagavat, or the most beautiful. It may be also translated the beautiful Shoma or Soma.

In the Amara-cosa, and commentary, it is called Sausami in a derivative form from Su-sami.

It is declared there to be in the famous and extensive country of Usinara. The reason for its being introduced into that work is because there is in it a city called Cantha and Sau-sami-cant'ha. This word is of the neuter gender, provided the compound term be the name of a town in Usinara, else it is feminine. Example: Sau-sami-cantha, and Dacshina-cantha, names of towns; the first in Usinara, the other out of that country.* [Amara-cosa, and translation by Mr. Colebrooke, p. 385.] These two towns still exist: the first, in the late surveys made by order of Government, is placed on the western bank of the Rama-ganga, in 29° 7" of latitude: the other, or south Cantha, is in the district of Budayoon, and is the head place of the Purgunah of Kant according to the Ayin Acberi.* [Ayin Acberi, Vol. 2d Tucseem Jumma, p. 84.]

There is little doubt but that the Soma or Sami is the Isamus of Strabo, the boundary of Menander's kingdom.† [Strabo Lib. 11, p. 516.]

The beautiful Vama was mentioned by Megasthenes, as a river falling into the Ganges,

according to Pliny. This river consists of two branches, the Western is called Gangan,

according to the late surveys made by order of Government; the eastern branch is the Ram-ganga, and they unite about twenty miles to the south of Rampoor.

On the banks of the former lived the Gangani of Ptolemy[???] called Tangani in some copies. The next river is the

Gaura[???], Gauri[???], or Gaurani[???]. There are many rivers so called, but it is

doubtful whether this was meant by the Pauranics. The

inhabitants of the country call it so, this is sufficient authority, and it

is probably the Agoranis of Megasthenes. But I am unable to give with assurance of being accurate any information regarding the regions beyond the Hyphasis, since the progress of Alexander was arrested by that river. But to recur to the two greatest rivers, the Ganges and the Indus, Megasthenes states that of the two the Ganges is much the larger, and other writers who mention the Ganges agree with him; for, besides being of ample volume even where it issues from its springs, it receives as tributaries the river Kainas, and the Erannoboas, and the Kossoanos, which are all navigable. It receives, besides, the river Sonos and the Sittokatis, and the Solomatis, which are also navigable, and also the Kondochates, and the Sambos, and the Magon, and the Agoranis, and the Omalis.

Moreover there fall into it the Kommenases, a great river, and the Kakouthis, and the Andomatis, which flows from the dominions of the Madyandinoi, an Indian tribe. In addition to all these, the Amystis, which flows past the city Katadupa, and the Oxymagis from the dominions of a tribe called the Pinzalai, and the Errenysis from the Mathai, an Indian tribe, unite with the Ganges.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., 1877

The Gomati [Gumti/Gomti/Gumati/Gomati in Gangladesh: Wiki], or Vasishti[???] river, is called

in the spoken dialects Gumti. About fifty miles above Lucknow it divides into two branches, which unite again below Jounpoor.

The eastern branch retains the name of Gumti; the western branch is called Sambu and Sucti, and in the spoken dialects Sye, because it abounds with small shells. This is really the case, as I have repeatedly observed, whilst surveying, or travelling along its banks. They are all fossile, small and imbedded in its banks, and appear here and there when laid bare by the encroachments of the river. They consist chiefly of small cockles and periwinkles. Many of them look fresh, the rest are more or less decayed, and they are all empty.

I know several other rivers so called, and for the same reason. In the spoken dialects, their name is pronounced

Sye as here, Soy and Sui, at other places, from the Sanscrit Sucti. This river is not mentioned in any Sanscrit book that I ever saw, but

I take it to be the Sambus of Megasthenes.

The next river is

the Sarayu, called also Devica and Gharghara; in the spoken dialects Sarju, Deva, Deha and Ghaghra. The Pauranics consider these three denominations as belonging to the same river. The natives here are of a different opinion; they say that Dewa and Ghaghra are the names of the main stream, and the Sarju a different river as represented in Major Rennell’s maps. The Sarju comes from the mountains to the eastward of the Dewa, passes by Baraich, and joins the Dewa above Ayodhya or Oude, and then separating from it below that town it crosses over to the other side, that is to say to the westward of it, and falls into the Ganges at

Bhrigurasrama, in the spoken dialects Bagrasan. In the Cshetra-samasa it is declared that the Gharghara is the true and real Sarayu, and that it is called Maha-sarayu or great Sarayu, and the other is the little Sarayu. According to the above Geographical Treatise[???], the

Sarayu is also called Prema-bahini, or the friendly stream. Towards the west it sends

a branch called in the Puranas Tamasi, and in the spoken dialectics and in the maps Tonsa: it is a most holy stream, and joins the lesser Saraya in the lower parts of its course.

It is omitted by Ptolemy, but it is the large river called by Megasthenes Commenases, or the Comaunish river, because it comes from the country of Comaunh, called also Almorah. It is called Ocdanes by Artemidorus as cited by Strabo, because it flows by the town and through the country of Oude, called Oeta by the poet Nonnus. The

Gharghara is called Gorgoris by the Anonymous of Ravenna: for thus I read, instead of Torgoris, as the original documents were in the Greek language, in which there is very little difference between the letters T and Greek [x].

The Ravenna Cosmography (Latin: Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia, lit. "The Cosmography of the Unknown Ravennese") is a list of place-names covering the world from India to Ireland, compiled by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna around 700 AD. Textual evidence indicates that the author frequently used maps as his source.

There are three known copies of the Cosmography in existence. The Vatican Library holds a 14th-century copy, there is a 13th-century copy in Paris at the Bibliothèque Nationale, and the library at Basle University has another 14th-century copy. The Vatican copy was used as the source for the first publication of the manuscript in 1688 by Porcheron...

The naming of places in Roman Britain has traditionally relied on Ptolemy’s Geography, the Antonine Itinerary and the Peutinger Table [The layout of the road network of the Roman Empire. The map is a 13th-century parchment copy of a possible Roman original. It covers Europe (without the Iberian Peninsula and the British Isles), North Africa, and parts of Asia, including the Middle East, Persia, and India.], as the Cosmography was seen as full of corruptions, with the ordering of the lists of placenames being haphazard. However, there are more entries in the Cosmography than in the other documents, and so it has been studied more recently...

Part of the difficulty with the text is its corruption, which probably results from the author failing to understand his sources, or not appreciating the purpose for which they were written. His original sources may have been of poor quality, resulting in many curious-looking names appearing in the lists. Equally, there are some obvious omissions, although the author was not attempting to produce a complete list of places, as his introduction states: "In that Britain we read that there were many civitates and forts, of which we wish to name a few." The suggestion that he was using maps is bolstered by phrases such as "next to" which occur frequently, and at one point he states: "where that same Britain is seen to be narrowest from Ocean to Ocean." Richmond and Crawford were the first to argue that rather than being random, the named places are often clustered around a central point, or spread out along a single road. For most of England, the order seems to follow a series of zig-zags, but this arrangement is less obvious for the south-west and for Scotland.

-- Ravenna Cosmography, by Wikipedia

The Rava, or noisy river, is mentioned in the lists of countries in the Puranas, otherwise it is but little known. In a derivative form it becomes Ravati, and in the spoken dialects Rabti and Rapti. The Gandaci, or Gandacavati, is called

Gandac in the spoken dialects, and it is the Condochates of Megasthenes. This river is left out by Ptolemy; but it is obvious, at least to me, that he had documents about it and the Sarayu, which either he did not well understand, or were very defective. B.C. 325... B.C. 315... At this period the capital of India was Pataliputra or Palibrotha, which was situated on the Ganges, at the junction of the Erranaboas or Alaos river. The former name has been identified with the Sanskrit Hiranyabahu, an epithet which has been applied both to the Gandak [Gandaki] and to the Sone. The latter name can only refer to the Hi-le-an of the Chinese travellers, which was to the north of the Ganges, and was there undoubtedly the Gandak [Gandaki].-- The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, by Surgeon General Edward Balfour, 1885

All rivers to the north of the Ganges flow in general towards the south, declining more or less toward the east.

Here Ptolemy has a river, which, according to him, flows directly towards the south-west, and he has very properly bestowed no name upon it. What is remarkable is that the source of this imaginary river is really that of the Gandaci, and its confluence [junction] with the Ganges is that of the Dewa.

On its banks he has a town called Cassida, the Sanscrit name of which is Cushadha, or Cusadya, the same with Oude; and, as it were to complete the sum of blunders, he has placed Canogiza, or

Canoge on its banks. According to Ptolemy, the source of this river is in the northern hills, at a place which he calls Selampura, (as it is written and accentuated in the Greek original), at the foot of mount

Bepyrrhus, so called from numerous passes through it and called to this day Bhimpheri, synonymous with Bhay-pheri or the tremendous passes, as we have seen before.

Selampoor is really a Sanscrit name of a place, Sailapura, or Sailampur, for both are grammatical, and are synonymous with Sailagram, and the obvious meaning, and we may say the only one of both, is the town of Saila, which signifies

a rocky hill.

Enthusiasts, have endeavoured to frame etymologies suitable to the rank, and dignity of this stone, which is a deity, and is god in its own right, for it is Vishnu: but they are rejected by sober and dispassionate Pandits, as too far fetched, and sometimes ridiculous. The name of this stone is written Salagram, Sailagram, Saila-chacra, and Gandaci-Sila. People who go in search of the Salagram, travel as far as a place called Thacca-cote, at the entrance nearly of the snowy mountains. To the south of it is a village where they stop and procure provisions.

This village was probably called Sailapur or Sailagram from its situation near a Saila or rocky hill, and from it this famous stone was denominated Sailagram, as well as the river. Thacca is mentioned in Arrowsmith’s map.

The origin of this rocky hill is connected with a most strange legend, which I shall give in the abstract. Vishnu, unwilling to subject himself to the dreaded power and influence of the ruler of the planet Saturn, and having no time to lose, was obliged to have recourse to his Maya, or illusive powers, which are very great, and he suddenly became a rocky mountain. This is called Saila-maya, of a rocky mountain the illusive form: but Saturn soon found him out, and in the shape of a worm forced himself through, gnawing every part of this illusive body. For one year of Saturn was Vishnu thus tormented, and through pain and vexation he sweated most profusely, as may be supposed, particularly about the temples, from which issued two copious streams, the Crishna or black, and the Sweta-Gandaci, or white Gandaci; the one to the east, and the other to the west. After one revolution of Saturn, Vishnu resumed his own shape, and ordered this stone to be worshipped, which of course derives its divine right from itself, without any previous consecration, as usual in all countries in which images are worshipped.

There are four stones, which are styled Saila-maya, and are accordingly worshipped whenever they are found. The first is the Saila, or stone just mentioned; the second, which is found abundantly in the river Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], is

a figured stone, of a reddish colour, with a supposed figure of Ganesa in the shape of an elephant, and commonly called Ganesa-ca-pathar: the third is found in the Narmmada; and

the fourth is a single stone or rock which is the Saila-maya, of the third part of the bow of Parasu-Rama, after it had been broken by Rama-chandra. It is still to be seen, about seven Cos to the N.E. of Janaca-pura in Taira-bhucta, at a place called Dhanuca-grama, or the village of the bow, occasionally called Saila-maya-pur, or grama, according to the Bhuvana-cosa.

The river Gandaca is so called because it proceeds from a mountain of that name. The people of Naypala call it Cundaci because it proceeds from the Cunda-sthala, or the two cavities, or depressions of the temples of Vishnu, in the shape of a mountain as I observed before.

It is also called Sala-grama, because of the stone of that name round in its bed. Another name for it is Narayani, because Vishnu or Narayana abides in its waters, in the shape of the above stone. There is a place, near Janaca-pura, which as I observed before, it called Saila-maya-pura or Saila-maya-grama, and which becomes Saila-pura, or Saila-grama, in the spoken dialects.* [In the original MS. these words are written Sala-maya, Sati-pura and Sali-grama, that is to say, they have adopted the pronunciation of these words such as it is in the spoken dialects. This is occasionally the case in geographical books in the Sanscrit language.]

Some believe the Saila-gram to be the eagle stone: if so it is not a new idea; for Matthiolus, who lived I believe towards the latter end of the fifteenth century, says that eagles do keep most carefully such a stone by them, and that for this purpose they travel to India in order to procure it. For without it the eggs in their nests would infallibly rot and be spoiled.

The next river is the

Bagmati [Bagmati/Kareh: Wiki] or Bangmati, that is to say, full of noises and sounds. According to the Himavat-chanda, a section of the Scanda-purana, it comes from two

springs in the skirts of the peak of Siva. The eastern spring is the Bagmati, and

the western is called after Harineswara or Harinesa, or the lord in the shape of an antelope. We read in the above section that

Siva once thought proper to withdraw from the busy scenes of the world, and to live incognito in the shape of an ugly and deformed male antelope, that he might not be recognised by his wife, and by the gods, who he knew would immediately go in search of him, as he was one of the three grand agents of the world. He was not mistaken; for 10,000 years of the gods they searched for him all over the world but in vain. His lubricity at last led to the discovery, for some of the gods took particular notice of the behaviour of an ugly male antelope, and they wisely concluded that it was Siva himself in that shape. Since that time Siva is worshipped along the banks of the Bagmati under the title of Harineswara, or Harinesa. The peak we mentioned before is called to this day, according to Colonel Kirkpatrick, Sheopoory, the place or abode of Siva, or Seo. The pool, where he and his female friends used to allay their thirst, is called in the above Purana Mrigasringodaca, or Harinasringodaca, or the water of the peak of the antelope, meaning Siva in that shape. The western branch again flows into the Bagmati, and

I believe that it once communicated its name Harinesi to that river; and similar instances occur occasionally in India. Hence

I suppose that it is the Erineses of Megasthenes who besides says that it ran into the Ganges through the country of the Mathae. This country is that of Tirhut, called also in Sanscrit Maitha, and Maithila from a Raja whose father was called Mitha, and from him the son was called, in a derivative form, Maitha and Maithila.