Prince Peter’s Seven Years in Kalimpong: Collecting in a Contact Zone

by Trine Brox and Miriam Koktvedgaard Zeitzen

January, 2017

Kalimpong Main Road, RCM Road 1950

Abstract

The main protagonist of this paper is H.R.H. Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark (1908–1980), an old-world ethnographer and explorer who went to Kalimpong in the 1950s, first as a member and later as the leader of the Third Danish Expedition to Central Asia. The expedition’s aims were to explore and document empty spots on the map and to rescue the remnants of local cultures in Upper Asia. With the developing crisis in Tibet, however, Prince Peter was stranded in Kalimpong, waiting in vain for permission to enter Tibet. Yet unfavourable political circumstances turned into great opportunities for the expedition as the advance of the People’s Liberation Army into Tibet led to a stream of refugees into Kalimpong: “We had been denied entry into Tibet, but Tibet had come to us.” In this article, we explore Prince Peter’s seven years in Kalimpong and how he navigated this particularly intense contact zone, negotiating difficult political, personal, and professional circumstances.

Introducing Prince Peter in Kalimpong

H.R.H. Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark was an old-world ethnographer and explorer who embodied the intellectual aristocrat who travelled in style to exotic places to study the local flora, fauna, and folk.1 His mother’s vast fortune supported Prince Peter and enabled him to dedicate his life to his travels and the pursuit of adventure on his own professional— and personal—terms. Yet this description fails to do justice to the thirst for knowledge and the quest to make scientific discoveries that drove him to travel to the far reaches of the world. In 1950, his travels took him to the north-east Indian Himalayan town of Kalimpong—“the little frontier town at the very gate of central Tibet” (Prince Peter 1963, 581). He arrived there in 1950 as part of, and later as the leader of the Third Danish Expedition to Central Asia. He was aiming for Tibet, but ended up staying in Kalimpong for seven years.2 During those years, based in Kalimpong, Prince Peter not only became entangled in intense and sometimes conflictual political and personal relations with society there, but he also faced tremendous professional challenges because the expedition was stranded in this Himalayan town and unable to follow its intended trajectory into Upper Asia.

Prince Peter’s unanticipated Kalimpong adventure nonetheless stands out from other ethnographic work done amongst Tibetans because of the variety and amount of material that he was able to collect during his stay there from January 1950 to February 1957. He acquired a rich collection of artefacts and books, photographs and moving images, sound recordings, and ethnographic information, as well as an astoundingly large body of physical anthropology data. He published several articles based on the data from the expedition, covering topics ranging from fraternal polyandry to anthropometrical studies, as well as investigations of Tibetan oracles, aristocrats, Muslims, and many others. Our preliminary inquiry reveals that between 1935 and 1980, Prince Peter published six books and over sixty articles, many of them for the general public. He also produced sixteen anthropological films. Almost half of his work was published in the 1950s, professionally his most productive decade.3

Prince Peter’s Kalimpong years were not only his most productive professionally, but also his most intense, personally and politically. For Prince Peter, and the many other explorers, ethnographers, and adventurers who lived in or travelled through the town, Kalimpong came to constitute a complex contact zone—one of those “social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of dominance and subordination” (Pratt 1992, 4). Contact zones are, from Marie Louise Pratt’s perspective, fluid places and spaces of exchange and connectivity, spaces shaped by European expeditions into non-European worlds (Pratt 1992). Therefore, the concept of a contact zone is a useful tool for framing and understanding the many encounters and exchanges between the local and the global, the national and the transnational, and between identity and diversity, that took place during Prince Peter’s sojourn in Kalimpong—a sojourn which in many and varied ways embodies the West’s encounter with “the rest.”

Thus, Prince Peter’s stationary expedition work obtaining permits, collecting artefacts, and interacting with interlocutors in Kalimpong could be understood as activities that took place within a complex contact zone. This paper represents a first attempt at exploring the ways in which Prince Peter’s scientific pursuits became entangled with political and personal dramas in this multi-layered contact zone, where people from a variety of socio-cultural and ethnic-linguistic backgrounds moved in and out, oscillating between placement and displacement. We will investigate Kalimpong as a fluid and dynamic place containing various spaces of exchange and connectivity in which Prince Peter interacted with interlocutors, and will explore the transcultural knowledge spaces that emerge from their encounters. For analytical purposes, and to do justice to Prince Peter’s many entanglements, we have conceptually subdivided Kalimpong into a geopolitical, an interpersonal, and an ethnographic contact zone. How Prince Peter navigated these multiple and complex contact zones, constantly negotiating difficult political, personal, and professional circumstances in a stream of social and cultural encounters and scientific challenges is one of the focal points of this paper.

Our second focal point is Prince Peter’s initially reluctant abandonment of the expedition mode in favour of a more contemporary way of doing ethnographic fieldwork, that is, intense study in particular spaces. Operating within the old fashioned expedition mode, Prince Peter had been determined to travel to far-off places to penetrate new and unexplored worlds in order to document the many facets of the exotic and unknown civilizations he expected to encounter. He was part of a team composed of anthropologists, archaeologists, geographers, botanists, meteorologists, and religious studies scholars—scholars whose expertise, the result of their different scientific methods, was considered necessary to map out in their entirety the various constituents of a civilization. The team of Danish explorers was supposed to pass through Kalimpong, yet rather than being the intended gateway to Tibet, the town came to constitute a particular space in which Prince Peter conducted intense studies of Tibetans and their culture. As time passed and the expedition continued to be denied entry to Tibet, the other members of the expedition left one by one, and Prince Peter came to represent the expedition single-handedly, carrying the flag of the Explorers’ Club, both metaphorically and literally, as the expedition’s sole remaining participant.

In Kalimpong, Prince Peter attempted to salvage both tangible Tibetan cultural heritage, on commission from the Danish National Museum, and intangible cultural heritage, documenting particular Tibetan lifeways such as polyandry for posterity (Koktvedgaard Zeitzen 2008; Prince Peter 1963). Prince Peter’s stay in Kalimpong foreshadowed contemporary anthropological fieldwork, where ethnographers work with people where they are when the fieldwork is being done, rather than where they are considered to have originated from. In 1950s Kalimpong, where both Prince Peter and his Tibetan interlocutors were embroiled in personal struggles of various kinds, the narrative identity they created was dynamic—and displaced. However, Prince Peter’s goal was not to understand contemporary Tibetan lifeways in Kalimpong but rather, to collect and document Tibetan heritage as it was practiced where, in his view, it had originally belonged, that is, in Tibet proper. He filters his Tibetan interlocutors’ accounts and artefacts through his own acquired anthropological narratives about Tibet, and, using this filter, extracted those elements he thought embodied authentic Tibetan cultural lifeways. By exploring Prince Peter’s work in Kalimpong as taking place within a complex and contested contact zone, this paper attempts to take some initial steps in exploring his production of ethnographic knowledge and its entanglement with his Tibetan interlocutors and their own bodies of knowledge.

H.R.H. Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark

H.R.H. Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark was born in Paris in 1908. He was the son of Prince Georg of Greece and Denmark, brother to the Greek king. His mother was the famous psychiatrist Marie Bonaparte, who came from the immensely wealthy Blanc family of France, whose fortune derived from the Monte Carlo Casino. She became a psychiatrist after becoming a patient and later a close friend of Sigmund Freud; she is well-known for paying the ransom that enabled him to leave German-occupied Austria in 1938. Prince Peter’s maternal grandfather was Prince Roland Napoléon Bonaparte, grandson of Emperor Napoleon’s brother Lucien, and a famous botanist and explorer in his own right. He was a member of the 1886 French scientific expedition to northern Norway, where he photographed and took anthropometric measurements of indigenous Sami people (Bonaparte 1886).

Anthropometry was used extensively by anthropologists studying human and racial origins: some attempted racial differentiation and classification, often seeking ways in which certain races were inferior to others. Nott translated Arthur de Gobineau's An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853–1855), a founding work of racial segregationism that made three main divisions between races, based not on colour but on climatic conditions and geographic location, and privileged the "Aryan" race. Science has tested many theories aligning race and personality, which have been current since Boulainvilliers (1658–1722) contrasted the Français (French people), alleged descendants of the Nordic Franks, and members of the aristocracy, to the Third Estate, considered to be indigenous Gallo-Roman people subordinated by right of conquest.

François Bernier, Carl Linnaeus and Blumenbach had examined multiple observable human characteristics in search of a typology. Bernier based his racial classification on physical type which included hair shape, nose shape and skin color. Linnaeus based a similar racial classification scheme. As anthropologists gained access to methods of skull measure they developed racial classification based on skull shape.

Theories of scientific racism became popular, one prominent figure being Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), who in L'Aryen et son rôle social (1899 - "The Aryan and his social role") divided humanity into various, hierarchized, different "races", spanning from the "Aryan white race, dolichocephalic" to the "brachycephalic" (short and broad-headed) race. Between these Vacher de Lapouge identified the "Homo europaeus (Teutonic, Protestant, etc.), the "Homo alpinus" (Auvergnat, Turkish, etc.) and the "Homo mediterraneus" (Napolitano, Andalus, etc.). "Homo africanus" (Congo, Florida) was excluded from discussion. His racial classification ("Teutonic", "Alpine" and "Mediterranean") was also used by William Z. Ripley (1867–1941) who, in The Races of Europe (1899), made a map of Europe according to the cephalic index of its inhabitants.

Vacher de Lapouge became one of the leading inspirations of Nazi anti-semitism and Nazi ideology. Nazi Germany relied on anthropometric measurements to distinguish Aryans from Jews and many forms of anthropometry were used for the advocacy of eugenics. During the 1920s and 1930s, though, members of the school of cultural anthropology of Franz Boas began to use anthropometric approaches to discredit the concept of fixed biological race. Boas used the cephalic index to show the influence of environmental factors...

Several studies have demonstrated correlations between race and brain size, with varying results. In some studies, Caucasians were reported to have larger brains than other racial groups, whereas in recent studies and reanalysis of previous studies, East Asians were reported as having larger brains and skulls. More common among the studies was the report that Africans had smaller skulls than either Caucasians or East Asians. Criticisms have been raised against a number of these studies regarding questionable methods.

In Crania Americana Morton claimed that Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Indians were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches. In 1873 Paul Broca (1824–1880) found the same pattern described by Samuel Morton's Crania Americana by weighing brains at autopsy. Other historical studies alleging a Black-White difference in brain size include Bean (1906), Mall, (1909), Pearl, (1934) and Vint (1934). But in Germany Rudolf Virchow's study led him to denounce "Nordic mysticism" in the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe. Josef Kollmann, a collaborator of Virchow, stated in the same congress that the people of Europe, be them German, Italian, English or French, belonged to a "mixture of various races," furthermore declaring that the "results of craniology" led to "struggle against any theory concerning the superiority of this or that European race". Virchow later rejected measure of skulls as legitimate means of taxonomy. Paul Kretschmer quoted an 1892 discussion with him concerning these criticisms, also citing Aurel von Törok's 1895 work, who basically proclaimed the failure of craniometry.

-- History of anthropometry, by Wikipedia

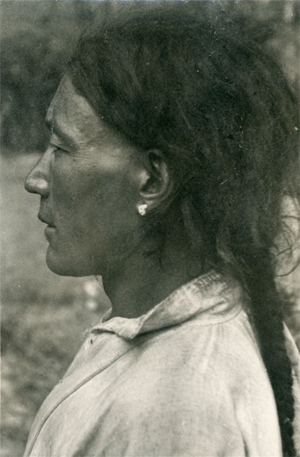

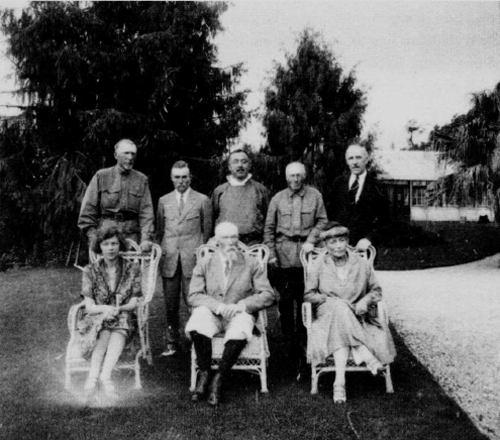

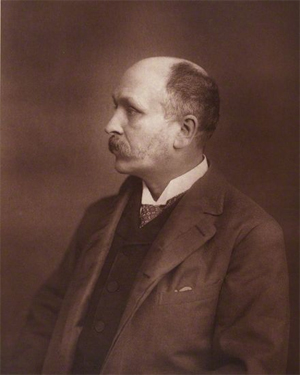

Figure 1: Irina taking a rest on her way to Ladakh with Prince Peter in 1938; their pre-war Himalayan journey is described in Prince Peter’s book Chevauchée tibétaines, Fernand Nathan, Paris 1958.

Prince Peter led a life of luxury and enjoyed the high social status befitting his royal birth, yet when he married the twice-divorced Russian socialite Irina Alexandrovna Ovtchinnikova (b. 1904 in Saint Petersburg, d. 1990 in Paris) in Madras in 1939, his fortunes took an abrupt turn. His family did not approve of the marriage, and he was banished from the royal inner circles in Greece and Denmark. Distant places might have seemed even more attractive to the prince after his familial déroute, and his wife remained his loyal and intrepid companion during all his subsequent travels. Prince Peter’s mother also remained devoted to her son, albeit at a distance, and continued to pay his personal expenses and finance his professional endeavours even after his rift with the royal families.

In 1937–39, Prince Peter undertook his first anthropological expedition to South Asia (figure 1). Together with his wife, Prince Peter carried out fieldwork among polyandrous groups in Ladakh, the Himalayas, and on the Malabar Coast. He had been broadly educated, studying first in Paris at the Sorbonne, where he became Docteur en Droit in 1934 with a thesis on Danish cooperatives. In 1935, he began post-graduate studies in anthropology at the London School of Economics under the supervision of Bronislaw Malinowski. One of the founding fathers of modern anthropology, Malinowski pioneered ethnographic fieldwork as the hallmark of anthropological methodology. Malinowski may thus have inspired and encouraged Prince Peter to do intense, long-term fieldwork.

Prince Peter’s travels were interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War, during which he was stationed in Egypt as a captain in the Greek Army. He resumed his anthropological explorations in 1946 with an expedition to Afghanistan, and moved on to join the Third Danish Expedition to Central Asia in 1948. It was part of Denmark’s participation in the race between nations to explore what Prince Peter called “little-known parts of the world” (Prince Peter 1954, 229). The overarching goal of the expedition was to explore terra incognita in Upper Asia. It had two objectives: firstly to explore and document Upper Asia, which was considered a blank spot on the map, and secondly to rescue the remnants of local cultures, which were assumed to be soon lost to the world. The expedition team under the prince’s leadership was to head for Sikkim in the south, work its way to Lhasa and over the Tibetan Plateau to Alaša in Inner Mongolia, and from there into the territory of the “Yellow Uigurs” (Prince Peter 1954, 229).

Prince Peter arrived in Kalimpong in January 1950, intent on documenting Tibet, its people, and its culture, all of which were considered under threat from the encroaching modern world, which gave the expedition a sense of urgency.4 Tibet was perceived as an inaccessible, empty space on the map between India and China, yet to be discovered and documented by cartographers and ethnographers, a forbidden and isolated place that had to be forced open to reveal its secrets (Bishop 1989). In his book Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Race for Lhasa, Peter Hopkirk articulates such a vision of Tibet, circulating at the time of Prince Peter’s expedition: “Until the Chinese invasion, their spartan way of life had hardly changed since the Middle Ages. […] Like Shangri La, the ‘lost’ valley of James Hilton’s Lost Horizons, Tibet was a land where time stood still and people had not yet lost their innocence. It was this, perhaps above all else, which made it so alluring to trespassers from the West” (Hopkirk 1982, 7).5 Prince Peter summed up the Western—and masculine—ethos of their expedition: “The people of Tibet are still practically unknown. From an anthropological and ethnological point of view, the country is virgin ground” (Prince Peter 1952, 281).

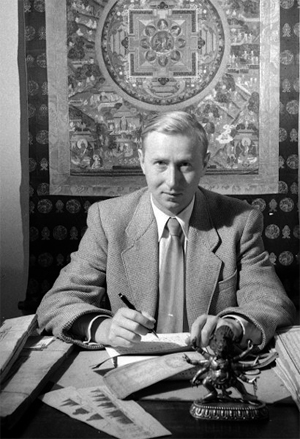

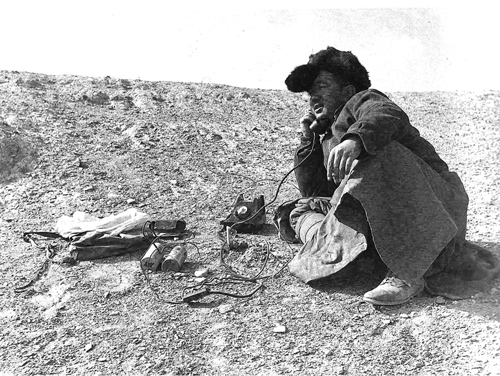

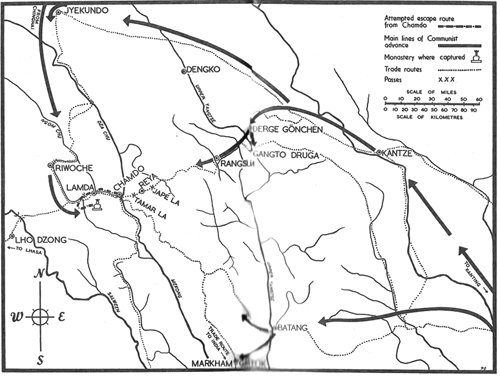

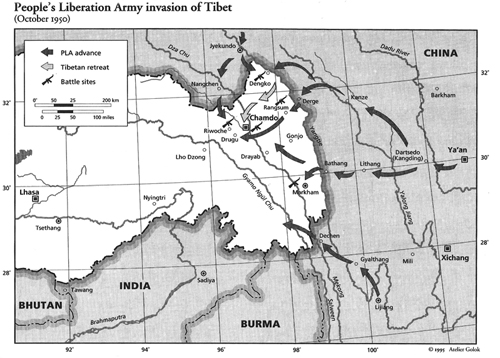

Prince Peter was unable to enter Tibet because of the tense political situation, and the advancement of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into Tibet in November 1950 left him stranded in Kalimpong. Yet the fruitless, seven-year wait for permission to enter Tibet nevertheless turned out to be Prince Peter’s most productive phase professionally, as the PLA’s presence in Tibet triggered a stream of Tibetan refugees into Kalimpong, creating a supply of potential interlocutors for his anthropological research (figure 2). He was, however, facing political, personal, and scientific challenges in this complex contact zone. From his exchange of letters with the Indian government and West Bengali authorities it is clear that they had little understanding of the scientific work he was doing. The Indian authorities grew increasingly concerned about him and his activities, in part because they suspected that his Russian wife was a spy. Eventually, Prince Peter and Irina were evicted from their house, and in February 1957 they left Kalimpong.

Spending seven years in Kalimpong and gaining first hand experience of Cold War politics and Communist China’s advance into Tibet, which pushed Tibetans into exile, Prince Peter became deeply engaged in the Tibetan cause. As President of the Nordic Council for Tibetan Assistance, he was instrumental in helping Tibetans go to Scandinavia in the 1960s.

The Nordic Council is the official body for formal inter-parliamentary Nordic cooperation among the Nordic countries. Formed in 1952, it has 87 representatives from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden as well as from the autonomous areas of the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and the Åland Islands. The representatives are members of parliament in their respective countries or areas and are elected by those parliaments. The Council holds ordinary sessions each year in October/November and usually one extra session per year with a specific theme...

In 1971, the Nordic Council of Ministers, an intergovernmental forum, was established to complement the Council. The Council and the Council of Ministers are involved in various forms of cooperation with neighbouring areas, amongst them being the Baltic Assembly and the Benelux,[4] as well as Russia[5] and Schleswig-Holstein.

During World War II, Denmark and Norway were occupied by Germany; Finland was under assault by the Soviet Union; while Sweden, though neutral, still felt the war's effects. Following the war, the Nordic countries pursued the idea of a Scandinavian defence union to ensure their mutual defence. However, Finland, due to its Paasikivi-Kekkonen policy of neutrality and FCMA treaty with the USSR, could not participate.

It was proposed that the Nordic countries would unify their foreign policy and defence, remain neutral in the event of a conflict and not ally with NATO, which some were planning at the time. The United States, keen on getting access to bases in Scandinavia and believing the Nordic countries incapable of defending themselves, stated it would not ensure military support for Scandinavia if they did not join NATO. As Denmark and Norway sought US aid for their post-war reconstruction, the project collapsed, with Denmark, Norway and Iceland joining NATO.

Further Nordic co-operation, such as an economic customs union, also failed. This led Danish Prime Minister Hans Hedtoft to propose, in 1951, a consultative inter-parliamentary body. This proposal was agreed by Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden in 1952. The Council's first session was held in the Danish Parliament on 13 February 1953 and it elected Hans Hedtoft as its president. When Finnish-Soviet relations thawed following the death of Joseph Stalin, Finland joined the council in 1955.

On 2 July 1954, the Nordic labour market was created and in 1958, building upon a 1952 passport-free travel area, the Nordic Passport Union was created. These two measures helped ensure Nordic citizens' free movement around the area. A Nordic Convention on Social Security was implemented in 1955. There were also plans for a single market but they were abandoned in 1959 shortly before Denmark, Norway, and Sweden joined the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). Finland became an associated member of EFTA in 1961 and Denmark and Norway applied to join the European Economic Community (EEC).

This move towards the EEC led to desire for a formal Nordic treaty. The Helsinki Treaty outlined the workings of the Council and came into force on 24 March 1962. Further advancements on Nordic cooperation were made in the following years: a Nordic School of Public Health, a Nordic Cultural Fund, and Nordic House in Reykjavík were created.

-- Nordic Council, by Wikipedia

In 1960, he helped arrange for twenty Tibetans aged eleven to sixteen to be educated in Denmark (Brox and Koktvedgaard Zeitzen 2016). His time in Kalimpong also fundamentally influenced his future academic trajectory. After returning to Europe, Prince Peter submitted his PhD dissertation on polyandry, based on his fieldwork in the Himalayas and southern India, to the London School of Economics. He received his PhD in 1959, and his seminal work on polyandry was published in 1963. He received an honorary doctorate from the University of Copenhagen in 1960, yet he never held an appointment at a university in Denmark or elsewhere. Nevertheless, he continued to travel and lecture at universities, explorers’ clubs, and various venues, and to publish on Tibetan matters for both an academic audience and the general readership. Prince Peter was finally allowed to enter Tibet in 1979—in post-Mao China, when Deng Xiaoping’s reforms opened the Tibetan plateau for Chinese business, immigration and tourism, and socio-economic reforms were intended to raise Tibet from the ruins of the Cultural Revolution. Prince Peter died a year later in London.

Kalimpong as a geopolitical contact zone

Figure 2: The photo bears the inscription “With compliments from Lakhmishand Kaluram. Kalimpong. 14/8/54” on the back; someone else has added that Prince Peter is standing next to the wife of a Tibetan Official.

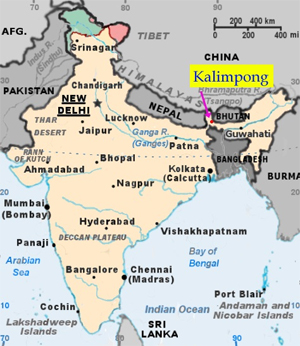

Kalimpong extends along a mountain ridge at a height of 1,300 meters in the Himalayan foothills of northern West Bengal, at the endpoint of a land corridor leading to Tibet. As the southern terminus of a commodity pathway starting at the Tibetan capital Lhasa and crossing over the Jelep mountain pass into India, it was the most important hill station in the region when Prince Peter stayed there. It had become the new economic capital of the region after the British Younghusband military expedition in 1903–4 forced entry into Tibet and opened a trade route between Lhasa and Calcutta. Goods coming from Tibet through Kalimpong could thus be transported to the commercial port of Calcutta, and shipped onward to Europe and America (Hackett ND; Harris 2008, 2013). As a globally connected centre of Indo-Tibetan trade, Kalimpong attracted people from all over, making the town a classic example of a contact zone fuelled by a complex web of cultural, ethnic, caste, religious, and linguistic encounters. It was, in the words of Prince Peter’s fellow scholar and friend René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz (figure 3), the “city of the seven new years,” because here “practically all peoples living in the Himalayas and adjacent territories” congregated and each group celebrated its new year according to its own calendar (Nebesky-Wojkowitz 1956b, 55, 66). The multitude of festivals testified to the cultural diversity of Kalimpong. Here, Tibetan, Marwari, Newari, and Kashmiri traders as well as Chinese merchants joined the many indigenous ethnic peoples and non-native groups coming and going to and from Kalimpong. Among them were Buddhist masters and their entourages, elite Tibetan politicians and nobility, royalty in exile, indigenous Lepchas, spies of the great powers, colonial holiday-goers, Scottish missionaries, European Tibetologists and ethnographers, and, following the PLA’s advancement into Tibet in 1950, an increasing number of Chinese and Tibetan refugees.

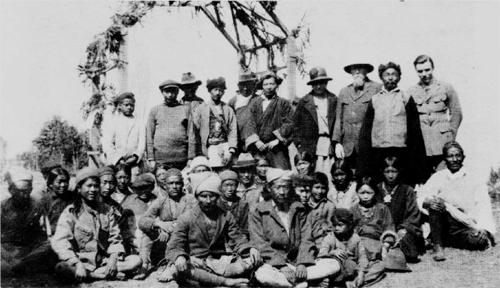

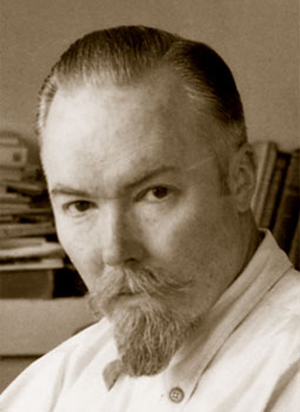

Figure 3: On their way to Gangtok. The three men are photographed outside the Himalayan Hotel in Kalimpong May 2, 1951. Next to Prince Peter is his friend and colleague René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz.

Kalimpong thus not only constituted a cultural juncture, it was also a frontier, a borderland, and a political edge. Wedged between Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Tibet, regional and national interests often converged and at times clashed in Kalimpong. In effect, it represented a Tibet in absentia, a player as well as a pawn in “the Great Game,” in which China, Russia, and Great Britain fought to gain a foothold in High Asia (Hopkirk 1990). Prince Peter stayed there at the height of the Cold War, when the agents of a newly independent India and competing empires congregated in Kalimpong, transforming it into a political gossip factory, and, in the words of Chinese President Mao Zedong, “a centre of espionage, primarily American and British” (quoted in Shakya 1999, 158). Indian President Nehru was indeed concerned about the number of potential spies, and he was under increasing pressure internally and externally as a result of the tense political situation. At a parliament hearing in the Lower House, Lok Sabha, he said about Kalimpong:

Kalimpong, Sir, has been often described as a nest of spies, spies of innumerable nationalities, not one, spies, spies from Asia, spies from Europe, spies from America, spies of Communists, spies of anti-Communists, red spies, white spies, blue spies, pink spies and so on. […] This has been going on for the last few years so there is no doubt that so far as Kalimpong is concerned there has been a deal of espionage and counter-espionage and a complicated game of chess by various nationalities and various members of spies and counter-spies there. No doubt a person with the ability to write fiction of this kind will find Kalimpong an interesting place for some novel of that type (Nehru 1959, 18–19).

Kalimpong, Sir, has been often described as a nest of spies, spies of innumerable nationalities, not one, spies from Asia, spies from Europe, spies from America, spies of Communists, spies of anti-Communists, red spies, white spies, blue spies, pink spies and so on. Once a knowledgeable person who knew something about this matter and was in Kalimpong actually said to me, though no doubt it was a figure of speech, that there were probably more spies in Kalimpong than the rest of the inhabitants put together. That is an exaggeration. But it has become that in the last few years, especially in the last seven or eight years. As Kalimpong is more or less perched near the borders of India, and since the developments in Tibet some years ago since a change took place there, it became of great interest to all kinds of people outside India, and many people have come here in various guises, sometimes as technical people, sometimes as bird watchers, sometimes as geologists, sometimes as journalists and sometimes with some other purpose, just to admire the natural scenery, and so they all seem to find an interest; the main object of their interest, whether it is bird watching or something else, was round about Kalimpong.

Naturally we have taken interest in this. We have to. While I cannot say that we know exactly everything that took place there, broadly we do know and we have repeatedly taken objection to those persons concerned or to their Embassies we have pointed this out and we have in the past even hinted that some people had better remove themselves from there, and they have removed themselves. This has been going on for the last few years so that there is no doubt that so far as Kalimpong is concerned there has been a deal of espionage and counter-espionage and a complicated game of chess by various nationalities and various numbers of spies and counter-spies there. No doubt a person with the ability to write fiction of this kind will find Kalimpong an interesting place for some novel of that type (Nehru 1959, 18-19, Parliament hearing in the Lower House, Lok Sabha)

Political intrigues, gossip, and accusations about espionage circulated in Kalimpong, and were related in books written by Western visitors to Kalimpong— some of whom did indeed report back to foreign agencies about their neighbours and friends (Nebesky-Wojkowitz 1956b; Patterson 1990; Sangharakshita 1997). It became infamous as a “nest of spies” (Patterson 1960, 71), a place with a highly volatile atmosphere in which suspicion and mistrust were widespread and had concrete consequences. Newly arrived residents and visitors were often seen as potential threats because of their possible ulterior motives for being in town. This atmosphere of suspicion engulfed Prince Peter as well as his wife Irina and his close friend Georg Nikolaivitch Roerich who, as Russian nationals, were both suspected of being Communist stooges. Another friend, Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai Lama’s elder brother, was suspected of being an agent of the Chinese Nationalists (Patterson 1990, 137). He later helped the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) work with a Tibetan émigré group gathering in Kalimpong to spearhead the Tibetan resistance and an anti-China campaign, creating a resistance network and planning a long-term guerrilla war (Shakya 1999; Knaus 1999; 2012).6 Kalimpong had become an important gathering place for Tibetan resistance directed towards Communist China, as well as a place of refuge for Tibetans fleeing Chinese expansion in Tibet as the PLA further advanced into Tibet and threatened India at its borders.

Kalimpong grew to be so important that for many Tibetans it became synonymous with all of India. For others, it was a Tibetan place (figure 4). According to Prince Peter, the town had a large ex-pat community of 3,500 Tibetan residents, including nobility, traders, and Tibetan Christians (Prince Peter 1963, 582). It also housed the famous Tibetan-language newspaper, the Tibet Mirror (yul phyogs so so’i gsar ’gyur gyi me long), which Dorje Tharchin had been publishing since 1925, and which circulated among the elite in Tibet for almost forty years (Hackett ND; McGranahan 2010, 69ff).

British-Indian intelligence reported that Kalimpong had an “extensive spy-network” by 1946 (SAWB, IB 1946, 4). We will probably never know about all the spies who operated in Kalimpong, but arguably the two most famous who appeared in Kalimpong were Gergan Dorje Tharchin, the editor of the Tibet Mirror, and Hisao Kimura, the “Japanese agent who disguised himself as a Mongolian pilgrim [… and] was recruited by the British Intelligence to gather information on the Chinese in Eastern Tibet” (Kimura 1990, book jacket). Tharchin had settled in Kalimpong and started his newspaper; with that he became of interest to the British, and also the Chinese, who tried to buy him.

-- Kalimpong: The China Connection, by Prem Poddar and Lisa Lindkvist Zhang

Being a Tibetan place also meant that European and American Tibetologists, anthropologists, political officers, trade officers, and explorers stayed in Kalimpong, either as a necessary stopover before proceeding to Tibet or as a replacement for a stay in Tibet. Famous Tibetophiles like Alexandra David-Néel, Georg Nikolaivitch Roerich, and René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz went there. Some rented or bought homes and settled in Kalimpong. Others stayed at the Himalayan Hotel, from which important information, gossip, and misinformation about Tibet was circulated (Nebesky-Wojkowitz 1956b; Sangharakshita 1997).

What is now the ‘Mayfair Himalayan Spa Resort' was previously the iconic ‘Himalayan Hotel’. It was established by David MacDonald, an ‘Anglo-Himalayan’ born to a Sikkimese mother and a Scottish father. During his long service as an interpreter and then a trade agent Mr MacDonald came in close contact with the 13th Dalai Lama. When His Holiness decided to escape Tibet to India it was David MacDonald who helped him.

Later impressed with his service, Mr MacDonald was given by the British Government a choice of either a title or European land parcel. David MacDonald asked for a particular plot of land in Kalimpong itself, next to his family home. Here, encouraged by his son-in-law Frank Perry, he established the ‘Himalayan Hotel’, the first hotel in the Darjeeling region. It was 1905, and the town of Kalimpong was a vibrant and flourishing town, because of the trade between Tibet and India. For years to come Mr MacDonald managed the hotel with his 3 daughters who were lovingly called ‘The three fat ladies of Kalimpong’.

Meanwhile there was another development: Nepal was declared a Hindu state and they closed it’s borders to all who aspired to climb Mt Everest, as they considered it sacrilegious; thus Kalimpong was the only way to the ‘south column’; thus the Himalayan Hotel became the favourite rendezvous for mountaineers. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay made their final plans of scaling the summit while staying in the ‘Himalayan Hotel’!!

In 1953 during the political unrest and with tensions brewing in the Indo- Chinese border, Pandit Jawarlal Nehru visited Kalimpong and stayed in the iconic hotel.

Over the years many Hollywood stars had also stayed in the iconic hotel. The Hollywood diva Shirley MacLaine stayed at the ‘Himalayan’ before leaving for Bhutan. When asked to sum up her stay she quoted the famous lines of George Bernard Shaw ‘The great advantage of a hotel is that it’s a refuge from home life’. These words somehow the essence of ‘Himalayan’. In 1991 Hollywood heartthrob Richard Gere and supermodel Cindy Crawford stayed in the ‘Himalayan’.

Even the glitz and glamour of Bollywood was not far from patronising the ‘Himalayan’. In 1965, Sunil Dutt, Nargis Dutt, along with Sanjay Dutt (then just 6 years old) stayed at the ‘Himalayan’. In 1974, Dev Anand and Zeenat Aman stayed in the hotel along with Shabana Azmi.

Now after 117 years and a rich legacy, the MacDonald family has decided to hand over the hotel to ‘Mayfair’ group. Now the ‘Himalayan Hotel’ is the ‘Mayfair Himalayan Spa Resort’. According to Mr Dilip Ray, the Chairman and Managing Director of Mayfair group, the essence of the hotel is still the same.

-- Of Royalty, Opulence , Luxury….A Stay at MAYFAIR, Kalimpong (The History), by madlyfoodlover.wordpress.com

Figure 4: Gopal Studio in Kalimpong published many photographs from the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s Kalimpong reception in 1956, and Prince Peter collected several of these. This picture captures contact zone encounters within a single frame.

Thus, at the height of the Cold War, an increasing number of visitors came to Kalimpong because it was the second-best thing to being in Tibet proper. Scottish missionary George Patterson remarked that numerous unidentifiable, questionable individuals came to Kalimpong at the height of the tension, when Kalimpong was “the most strategic town on the Chinese Communist route to Calcutta, and became a Communist constituency at this most critical period of Indo-Tibetan crisis” (Patterson 1990, 132). He observed how newspaper fantasies were fabricated because reporters, barred by obstructive Tibetan officials, were unable to enter Tibet. Instead they sought their information among Tibetan travelers in Kalimpong’s bazaars and among the foreigners who gathered at the Himalayan Hotel. They wired home reports about Tibet, which were partly from people’s imaginations and partly products of the Kalimpong rumor mill. Patterson called it “imaginative reporting.” Patterson himself reported to a foreign power, not in order to support any anti-Communist movement, but out of his “pro-God and pro-Tibet” convictions (Patterson 1960; 1990, 124).

The tense political situation produced severe obstacles, forcing Prince Peter to give up his original research design. He had arrived in Kalimpong in January 1950 and met the remnants of the first team of the Third Danish Expedition to Central Asia; the prince was a member of the second team. He intended to stay in Kalimpong primarily to arrange a permit for the expedition to enter Tibet. However, his repeated requests for a travel permit were looked upon with suspicion, since he and his expedition members were seen “as intruders with possibly suspicious ulterior motives” (Prince Peter 1963, 581). He abandoned the original goal of traversing the Tibetan plateau to reach Alaša in Inner Mongolia and the territory of the “Yellow Uigurs” (Prince Peter 1954, 229),...

A Yugur family in Lanzhou, Gansu, 1944

The Yugurs, Yughurs, Yugu or Yellow Uyghurs, as they are traditionally known, are a Turkic and Mongolic group ... The Yugur live primarily in Sunan Yugur Autonomous County in Gansu, China. They are Tibetan Buddhists...

The Turkic-speaking Yugurs are considered to be the descendants of a group of Uyghurs who fled from Mongolia southwards to Gansu after the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840, where they established the prosperous Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom (870-1036) with capital near present Zhangye at the base of the Qilian Mountains in the valley of the Ruo Shui. The population of this kingdom, estimated at 300,000 in Song chronicles, practised Manichaeism and Buddhism in numerous temples throughout the country.

In 1037 the Yugur came under Tangut domination. The Gansu Uyghur Kingdom was forcibly incorporated into the Western Xia after a bloody war that raged from 1028–1036.

The Mongolic-speaking Yugurs are probably the descendants of one of the Mongolic-speaking groups that invaded North China during the Mongol conquests of the thirteenth century. The Yugurs were eventually incorporated into Qing China in 1696 during the reign of the second Qing ruler, the Kangxi Emperor (1662–1723).

In 1893, Russian explorer Grigory Potanin, the first Western scientist to study the Yugur, published a small glossary of Yugur words, along with notes on their administration and geographical situation. Then, in 1907, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim visited the Western Yugur village of Lianhua (Mazhuangzi) and the Kangle Temple of the Eastern Yugur. Mannerheim was the first to conduct a detailed ethnographic investigation of the Yugur. In 1911, he published his findings in an article for the Finno-Ugrian Society.

About 4,600 of the Yugurs speak Western Yugur (a Turkic language) and about 2,800 Eastern Yugur (a Mongolic language). Western Yugur has preserved many archaisms of Old Uyghur. The remaining Yugurs of the Autonomous County lost their respective Yugur language and speak Chinese. A very small number of the Yugur reportedly speak Tibetan...

The Yugur people are predominantly employed in animal husbandry...

The traditional religion of the Yugur is Tibetan Buddhism, which used to be practised alongside shamanism.

-- Yugur [Yughurs] [Yugu] [Yellow Uyghurs], by Wikipedia

and instead found what he believed to be a more pragmatic solution, namely crossing the Indo-Tibetan border and following the traditional trade route to its northern terminus in Gyantse. According to Prince Peter’s account, neither the Political Officer in Sikkim nor “the Tibetans” wanted to take responsibility for Prince Peter’s scientific expedition, each of them responding to his request by referring him to the other (Prince Peter 1953b, 8–9).7 Prince Peter lamented that “in truly Oriental manner, they abstained from being either affirmative or negative” (Prince Peter 1963, 582) until August, when he was told to “kindly postpone my voyage” (Prince Peter 1954, 231).

When the PLA invaded eastern Tibet in October 1950, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, faced with the threat that the PLA would proceed to Lhasa, moved in December to Dromo, a small town near the Indo-Tibetan border (Shakya 1999, 51). In a last effort to obtain permission to enter Tibet, Prince Peter flexed his royal connections and got his cousin, King Paul of Greece, to provide him with a greeting that he could present to the Dalai Lama (Prince Peter 1953b, 10; 1954, 232). Prince Peter was not allowed, however, to present the introductory letter and the Greek king’s photograph to the Dalai Lama. These had the opposite effect on the Tibetans who—perhaps fearing a potential Chinese reaction—sealed Prince Peter’s fate, for he now found himself permanently stranded in Kalimpong, unable to enter Tibet: “We thus lost a last opportunity to visit the land before the Chinese military occupation in December of the same year” (Prince Peter 1952, 283). The final incorporation of Tibet into the People’s Republic of China (PRC) the following year, and the Chinese military presence all along the Indian border from Kashmir to Assam heightened tensions in the region: “it makes everyone on the border feel jittery, and, as usual, scientists are suspected of having deeper motives for being in those regions than is in fact the case” (Prince Peter 1953b, 10). Prince Peter’s expedition was thus forced to come to an end in Kalimpong, and he summed up his experience of the situation succinctly:

I have come to learn that international politics are the real obstacle to scientific research in these areas. The height of the Himalayan Barrier, the barrenness of the Tibetan high plateau, and the difficulties of supply and transport pale into insignificance when compared with this, the main impediment (Prince Peter 1954, 232).

Kalimpong as an interpersonal contact zone

Kalimpong was a cosmopolitan borderland en route to Tibet, Prince Peter’s ultimate destination which had been rendered unachievable by the PLA’s progression into Tibet. Instead, Kalimpong became a figurative route into Tibet for him: The many Tibetans pouring into town, along with the already existing community of Tibetan residents, became a huge potential pool of interlocutors. In addition, Kalimpong was a favourite seasonal refuge for Tibetans fleeing the cold Tibetan winters—a “Riviera for Tibet” (Prince Peter 1953a, 6). According to Prince Peter, the annual Tibetan traffic to or through Kalimpong amounted to as many as 15,000 Tibetans (Prince Peter 1953b, 9). He was thus able to get direct access to many Tibetans who otherwise would be unapproachable or difficult to meet during travels in Tibet proper. Moreover, the Dalai Lama and his government’s relocation to Dromo in December 1950 caused panic among Tibetan elites and prompted many of them to flee Tibet and move to Kalimpong (Harrer 1954; Shakya 1999, 51). This multiplied Prince Peter’s pool of potential interlocutors greatly: “a wave of Tibetan temporary refugees to Kalimpong, people generally of means, who decided to weather the storm on the Indian side of the frontier and see which way events would develop” (Prince Peter 1963, 582). It also increased Prince Peter’s pool of potential artefacts because the ruling elite who sent their families and their valuables across the border into safety were later willing to sell their belongings to him (Prince Peter 1953a, 10–11).

Tibetans arrived in large numbers in Kalimpong, where they bought or rented property to such an extent that the Development Area in Kalimpong “looked like a suburb of Lhasa” (Patterson 1990, 104). Tibetan officials and their families, Tibetan traders and pilgrims, as well as the few European residents of Tibet all fled to Kalimpong (figure 5). The Dalai Lama’s mother arrived there with his six siblings, and Prince Peter befriended the elder brother of the Dalai Lama, Gyalo Thondup (Knaus 2012, 309 n.18). The famous Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer came to Kalimpong after seven years in Tibet (Harrer 1954), as did the White Russian engineer Niedbylov, the English radio operator Reginald Fox, a Torgut Mongol prince with his family and retinue, twenty-three Russian Old Believers, and a steady “stream of refugees” (Prince Peter 1954, 232). They came to a cosmopolitan Kalimpong that included residents like the exiled prince and princess of the fallen Burmese royal family and the sister of the Sikkimese king, Chuni Wangmo, who was married to a Bhutanese prince (Shah 2012).

Prince Peter dealt with both destitute travellers and representatives of the Tibetan upper class, who met the prince as fellow aristocrats. His close friend Georg Nikolaivitch Roerich, a Tibet scholar and son of the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich, was instrumental in arranging meetings with prominent Tibetans, found good language teachers for Prince Peter so he could learn Tibetan, and helped him obtain ethnographical artefacts and books for his collection. Tibet scholar René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz was likewise Prince Peter’s close ally in the field, dedicating his monumental work Oracles and Demons of Tibet (1956a) to Prince Peter. Another traveller visiting Kalimpong at the time, James Cameron, wrote in his autobiography that the odd and endearing Kalimpong “had become a rendezvous for what was probably the most impressive collection of human eccentrics in Asia.” The people whom he met at the Himalayan Hotel were almost surrealistic: “wizards and sorcerers, Tibetan aristocrats, angry exiles from China, remote sprigs from the forgotten European nobility, Indian yogi, Bhutani politicians, professional anthropologists, linguists, students, pilgrims, miracle-workers and innocent bystanders, all milling around with curious axes to grind and trying either to get into Tibet, or to get out” (Cameron 1967, 204–205).

Around the time Seven Years in Tibet fell off the Best Seller List, the New York Times reported that the Dalai and Panchen Lamas were about to leave Tibet for Beijing at the PRC’s invitation192. The Dalai Lama left Lhasa in July 1954 and arrived in Beijing in September. In Beijing, the Dalai Lama attended the Chinese National People’s Congress, which produced the PRC’s first constitution, met Mao, attended numerous banquets and meetings, and greeted Nehru as the first head of a major non-Communist state to visit the PRC. The PRC also made sure the Dalai Lama and members of his delegation saw the PRC’s industrial achievements, which suitably impressed the Tibetans193.

The amount of coverage of the Dalai Lama’s trip to Beijing and tour of various locations throughout China was not great. In fact, the New York Times waited to publish a feature story or any photograph of the two incarnation’s tour until the PRC announced the formation of the Preparatory Committee for establishing the Tibet Autonomous Region (PCTAR) in March 1955194. In contrast to such prior coverage of the Dalai Lama as his flight to Yadong, what Americans read about the Dalai Lama’s journey to Beijing was quicker, more to the point, and sparser on details. Although the New York Times initially only reported that Tibetans urged him not to leave, tens of thousands turned out to watch the Dalai Lama’s five hundred man delegation depart while some cried and nearly threw themselves in the Kyichu River as the nineteen-year-old incarnation crossed in his special coracle195. Just as in coverage of the Dalai Lama’s flight to Yadong, there were physical and political limitations on what American reporters could see of events in Tibet, but American interest had clearly waned by this time. Americans were apparently eager for Harrer’s depiction of Tibet that struck a Lost Horizon tone, filled with excitement and adventure, but not for the reality of Tibet and the Dalai Lama’s ostensible cooperation with Communism.

Unlike coverage of the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet or the Dalai Lama’s flirtation with exile, there was a Western journalist in Beijing on hand to report his observations: James Cameron from the News Chronicle of London. The New York Times published several of Cameron’s dispatches, including one about how he accidentally managed to obtain the Dalai and Panchen Lamas’ autographs, with the Dalai Lama’s signature purposefully written first196. [196 James Cameron, “Red Delegations Flock to Peiping,” NYT, Nov. 1, 1954, 1.] Even though Americans could see events transpiring in Beijing through a Western journalist’s eyes, the American press put emphasis on other events occurring in Beijing over the Dalai Lama. Cameron’s journalism provided an extraordinary opportunity for Americans to receive eyewitness testimony on the two most important Tibetans behind the Bamboo Curtain, but Cameron’s own experience meeting the Dalai Lama was buried by his reporting on how much the PRC loved foreign delegations. Incidentally, Cameron also provided a means of historical corroboration when he sent his dispatch to the New York Times reporting Nehru’s unexpected encounter with the Dalai Lama. While Nehru was in Beijing for Sino-Indian talks, he unexpectedly ran into the Dalai Lama in a situation Cameron described as “piquant,” stating, “Mr. Nehru appeared to do a swift double-take, then embarked on a most animated conversation, to which the Dalai Lama replied with bemused nods.” To the Dalai Lama’s recollection, it was Nehru who was bemused and spoke only superficially197. Even though the PRC press made sure to waste no photo opportunity of Mao and the Dalai Lama together at the Tibetan New Year’s banquet in Beijing, the New York Times only published a 132 word blurb on the event, without a photograph198. The American press had at its disposal an unprecedented view of the boy god-king, but made little use of it.

[url]-- American Journalism and the Tibet Question, 1950-1959, by James August Duncan

Iowa State University[/url]

Time reported on December 4, 1950:

Tibet is only 30 miles away. For that reason, Kalimpong has collected over the years a number of mystical characters who arrived via Jelep-la pass from Tibet, and another bunch who would give their last rupee to travel the other way. Foreign cultists, scholars, artists, adventurers and missionaries plod Kalimpong’s streets, panting to explore Tibet and its particular brand of Buddhism, but lacking permission to get in. […] Last year anthropologist Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark breezed into Kalimpong with his wife to study a unique form of Tibetan polyandry called za-sum-pa, the sharing of wives between fathers and sons, and (occasionally) between uncles and nephews. Tibet would not admit the prince and princess (Time 1950).

Figure 5: Picture given to Prince Peter by Heinrich Harrer in Kalimpong, showing Tibetan official with child.

Despite his failure to enter Tibet, Prince Peter was nonetheless thrilled about the opportunities that Kalimpong offered. In 1954, he reported to the Royal Asiatic Society:

All this made the place we had perforce settled in a most interesting and lively one. […] Apart from the excitement of meeting all these strange and fascinating people, there were enormous possibilities of work. Very soon we had got down to interviewing them, purchasing clothes and valuables from them which we dispatched to the National Museum in Copenhagen and, after the Indian Government has made registration of all Tibetans with the police compulsory, measuring and describing them in order the better to find out what their physical racial characteristics were. We had been denied entry into Tibet, but Tibet had come to us, and under circumstances of stress which made it perhaps easier for us to obtain the results we wanted than if we had been working in the country under settled conditions (Prince Peter 1954, 231–2).

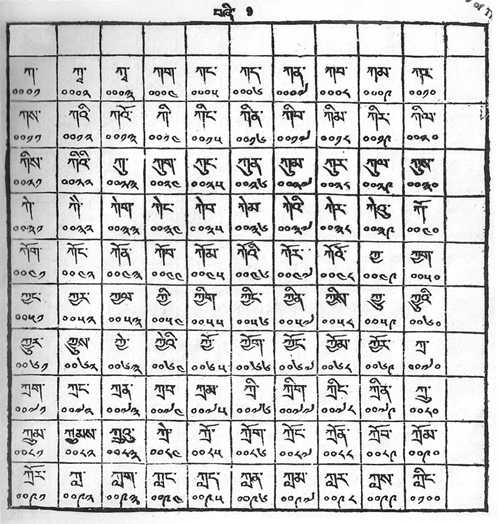

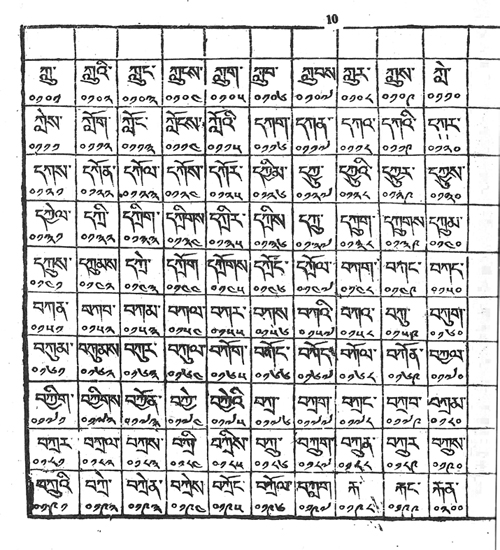

In terms of doing research, what had initially seemed like a disaster because of the expedition’s failure to enter Tibet, soon proved to grant unparalleled access to Tibetans from all walks of life and all regions of the country. This diversity is illustrated by the datasheets of the 5,000 individuals who came to Kalimpong from Tibet who Prince Peter measured anthropometrically. Of the 5,000 surveyed, 4,924 were Tibetans—4,411 males and 513 females, perhaps reflecting the gender composition of the general Tibetan refugee and trader population in Kalimpong, as opposed to that of the more settled Tibetan population. The people he measured came from all three Tibetan regions (Tib.: chol kha gsum), Utsang, Kham, and Amdo (figure 6). Prince Peter categorized his material according to these three indigenous categories, which in his view constituted Tibet, that is: taken together the three cohorts represented Tibet.8