by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/22/22

The Mudra Rakshasa is a drama of a very different description from either of the preceding, being wholly of a political character, and representing a series of Machiavelian stratagems, influencing public events of considerable importance. Those events relate to the history of Chandragupta, who is very probably identifiable with the Sandrocottus of the Greeks, and the drama therefore, both as a picture of manners and as a historical record, possesses no ordinary claims upon our attention....

The author of the play is called in the prelude Visakhadatta, the son of Prithu, entitled Maharaja, and grandson of the Samanta or chief Vateswara Datta. We are not much the wiser for this information...

The late Major Wilford has called the author of the Mudra Rakshasa, Ananta, and quotes him as declaring that he lived on the banks of the Godaveri (As. Res. vol. v. p. 280.) This however must be an error, as three copies, one of them a Dekhini manuscript in the Telugu character, have been consulted on the present occasion, and they all agree in the statement above given.

There is a commentary on the drama by Vateswara Misra, a Maithila Brahman, the son of Gauripati Misra, who has laboured with more pains than success to give a double interpretation to the composition, and to present it as a system of policy as well as a play.

Another commentary by Guhasena is said to exist, but it has not been met with; and the one referred to, owing to the commentator’s mystification of obvious meanings, and the exceedingly incorrect state of the manuscript, has proved of no advantage.

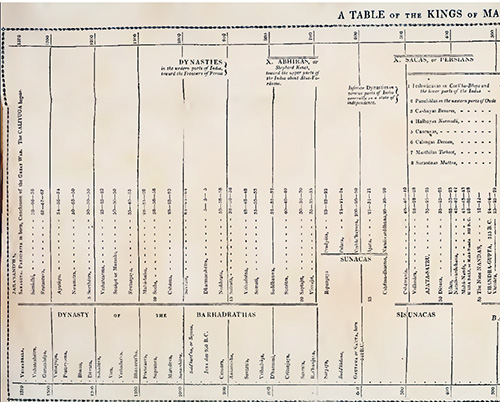

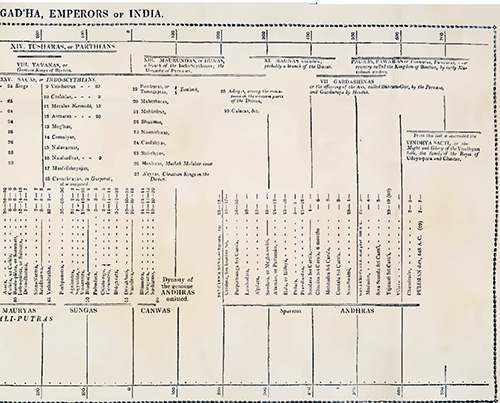

It may not here be out of place to offer a few observations on the identification of Chandragupta and Sandrocottus. It is the only point on which we can rest with any thing like confidence in the history of the Hindus, and is therefore of vital importance in all our attempts to reduce the reigns of their kings to a rational and consistent chronology. It is well worthy therefore of careful examination, and it is the more deserving of scrutiny, as it has been discredited by rather hasty verification and very erroneous details.

In the fifth volume of the Researches the subject was resumed by the late Colonel Wilford, and the story of Chandragupta is there told at considerable length, and with some accessions which can scarcely be considered authentic. He states also that the Mudra-Rakshasa consists of two parts, of which one may be called the coronation of Chandragupta, and the second his reconciliation with Rakshasa, the minister of his father. The latter is accurately enough described, but it may be doubted whether the former exists.

Colonel Wilford was right also in observing that the story is briefly related in the Vishnu-Purana and Bhagavata, and in the Vrihat-Katha; but when he adds, that it is told also in a lexicon called the Kamandaki he has been led into error. The Kamandaki is a work on Niti, or Polity, and does not contain the story of Nanda and Chandragupta. The author merely alludes to it in an honorific verse, which he addresses to Chanakya as the founder of political science, the Machiavel of India.

The birth of Nanda and of Chandragupta, and the circumstances of Nanda’s death, as given in Colonel Wilford’s account, are not alluded to in the play, the Mudra-Rakshasa, from which the whole is professedly taken, but they agree generally with the Vrihat-Katha and with popular versions of the story. From some of these, perhaps, the king of Vikatpalli, Chandra-Dasa, may have been derived, but he looks very like an amplification of Justin's account of the youthful adventures of Sandrocottus. The proceedings of Chandragupta and Chanakya upon Nanda's death correspond tolerably well with what we learn from the drama, but the manner in which the catastrophe is brought about (p. 268), is strangely misrepresented. The account was no doubt compiled for the translator by his pandit, and it is, therefore, but indifferent authority.

It does not appear that Colonel Wilford had investigated the drama himself, even when he published his second account of the story of Chandragupta (As. Res. vol. ix. p. 93 [p. 94-100]), for he continues to quote the Mudra-Rakshasa for various matters which it does not contain. Of these, the adventures of the king of Vikatpalli, and the employment of the Greek troops, are alone of any consequence, as they would mislead us into a supposition, that a much greater resemblance exists between the Grecian and Hindu histories than is actually the case.

Discarding, therefore, these accounts, and laying aside the marvellous part of the story, I shall endeavour, from the Vishnu and Bhagavata-Puranas, from a popular version of the narrative as it runs in the south of India, from the Vrihat-Katha, [For the gratification of those who may wish to see the story as it occurs in these original sources, translations are subjoined; and it is rather important to add, that in no other Purana has the story been found, although most of the principal works of this class have been carefully examined.] and from the play, to give what appear to be the genuine circumstances of Chandragupta's elevation to the throne of Palibothra.

Sir William Jones first discovered the resemblance of the names, and concluded Chandragupta to be one with Sandrocottus (As. Res. vol. iv. p. 11). He was, however, imperfectly acquainted with his authorities, as he cites "a beautiful poem” by Somadeva, and a tragedy called the coronation of Chandra, for the history of this prince. By the first is no doubt intended the large collection of tales by Somabhatta, the Vrihat-Katha [Kathasaritsagara], in which the story of Nanda's murder occurs: the second is, in all probability, the play that follows, and which begins after Chandragupta’s elevation to the throne.

-- The Mudra Rakshasa, or The Signet of the Minister. A Drama, Translated from the Original Sanscrit. Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, Translated from Original Sanskrit, in Two Volumes, Vol. II, by Horace Hayman Wilson, 1835

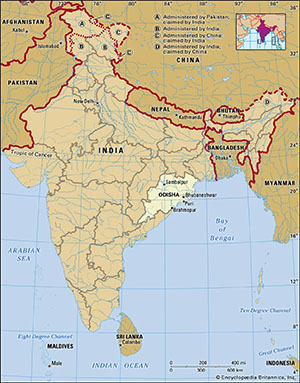

Patali-putra was certainly the capital, and the residence of the kings of Magadha or south Behar. In the Mudra Racshasa, of which I have related the argument, the capital city of Chandra-Gupta is called Cusumapoor throughout the piece, except in one passage, where it seems to be confounded with Patali-putra, as if they were different names for the same place. In the passage alluded to, Racshasa asks one of his messengers, “If he had been at Cusumapoor?” the man replies, “Yes, I have been at Patali-putra.” But Sumapon, or Phulwaree, to call it by its modern name, was, as the word imports, a pleasure or flower garden, belonging to the kings of Patna, and situate, indeed, about ten miles W.S.W, from that city, but, certainly, never surrounded with fortifications, which Annanta, the author of the Mudra Racshasa says, the abode of Chandra-Gupta was. It may be offered in excuse, for such blunders as these, that the authors of this, and the other poems and plays I have mentioned, written on the subject of Chandra-Gupta, which are certainly modern productions, were foreigners; inhabitants, if not natives, of the Deccan; at least Annanta was, for he declares that he lived on the banks of the Godaveri.

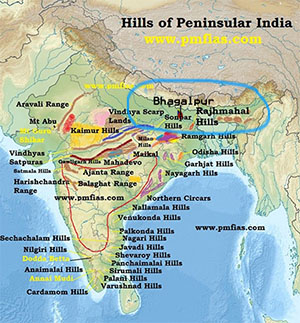

But though the foregoing considerations must place the authority of these writers far below the ancients, whom I have cited for the purpose of determining the situation of Palibothra; yet, if we consider the scene of action, in connexion with the incidents of the story, in the Mudra Racshasa, it will afford us clear evidence, that the city of Chandra-Gupta could not have stood on the site of Patna; and, a pretty strong presumption also, that its real situation was where I have placed it, that is to say, at no great distance from where Raje-mehal now stands. For, first, the city was in the neighbourhood of some hills which lay to the southward of it. Their situation is expressly mentioned; and for their contiguity, it may be inferred, though the precise distance be not set down from hence, that king Nanda's going out to hunt, his retiring to the reservoir, among the hills near Patalcandara, to quench his thirst, his murder there, and the subsequent return of the assassin to the city with his master's horse, are all occurrences related, as having happened on the same day. The messengers also who were sent by the young king after the discovery of the murder to fetch the body, executed their commission and returned to the city the same day. These events are natural and probable, if the city of Chandra-gupta was on the site of Raje-mehal, or in the neighbourhood of that place, but are utterly incredible, if applied to the situation of Patna, from which the hills recede at least thirty miles in any direction.

Again, Patalcandara in Sanscrit, signifies the crater of a volcano; and in fact, the hills that form the glen, in which is situated the place now called Mootijarna, or the pearl dropping spring, agreeing perfectly in the circumstances of distance and direction from Raje-mehal with the reservoir of Patalcandara, as described in the poem, have very much the appearance of a crater of an old volcano. I cannot say I have ever been on the very spot, but I have observed in the neighbourhood, substances that bore undoubted marks of their being volcanic productions; no such appearances are to be seen at Patna, nor any trace of there having ever been a volcano there, or near it. Mr. Davis has given a curious description of Mootijarna, illustrated with elegant drawings. He informs us there is a tradition, that the reservoir was built by Sultan Suja: perhaps he only repaired it.

The confusion Ananta and the other authors above alluded to, have made in the names of Patali-putra and Bali-putra, appears to me not difficult to be accounted for. While the sovereignty of the kings of Maghadha, or south Bahar, was exercised within the limits of their hereditary dominions, the seat of their government was Patali-putra, or Patya: but Janasandha, one of the ancestors of Chandra-Gupta, having subdued the whole of Prachi, as we read in the puranas, fixed his residence at Bali-putra, and there he suffered a most cruel death from Crishna and Bala Rama, who caused him to be split asunder. Bala restored the son, Sahadeva, to his hereditary dominions; and from that time the kings of Maghadha, for twenty-four generations, reigned peaceably at Patna, until Nanda ascended the throne, who, proving an active and enterprising prince, subdued the whole of Prachi; and having thus recovered the conquests, that had been wrested from his ancestor, probably re-established the seat of empire at Bali-putra; the historians of Alexander positively assert, that he did.[???]

Thus while the kings of Palibothra, as Diodorus tells us, sunk into oblivion, through their sloth and inactivity, (a reproach which seems warranted by the utter absence observed of the posterity of Bala Rama in the puranas, not even their names being mentioned;) the princes of Patali-putra, by a contrary conduct, acquired a reputation that spread over all India: it was, therefore, natural for foreign authors, (for such, at lead, Ananta was,) especially in competitions of the dramatic kind, where the effect is oftentimes best produced by a neglect of historical precision, of two titles, to which their hero had an equal right to distinguish him by the most illustrious. The author of Sacontala has committed as great a mistake, in making Hastinapoor the residence of Dushmanta, which was not then in existence, having been built by Hasti, the fifth in descent from Dushmanta; before his time there was, indeed, a place of worship on the same spot, but no town. The same author has fallen into another error, in assigning a situation of this city not far from the river Malini, (he should rather have said the rivulet that takes its name from a village now called Malyani, to the westward of Lahore: it is joined by a new channel to the Ravy;) but this is a mistake; Hastinapoor lies on the banks of the old channel of the Ganges. The descendants of Peru resided at Sangala, whose extensive ruins are to be seen about fifty miles to the westward of Lahore, in a part of the country uninhabited. I will take occasion to observe here, that Arrian has confounded Sangala with Salgada, or Salgana, or the mistake has been made by his copyists. Frontinus and Polyaenus have preserved the true name of this place, now called Calanore; and close to it is a deserted village, to this day called Salgheda; its situation answers exactly to the description given of it by Alexander's historians. The kings of Sangala are known in the Persian history by the name of Schangal, one of them assisted Asrasiab against the famous Caicosru; but to return from this digression to Patali-putra.

The true name of this famous place is, Patali-pura, which means the town of Patali, a form of Devi worshipped there. It was the residence of an adopted son of the goddess Patali, hence called Patali-putra, or the son of Patali. Patali-putra and Bali-putra are absolutely inadmissable, as Sanscrit names of towns and places; they are used in that sense, only in the spoken dialects; and this, of itself, is a proof, that the poems in question are modern productions. Patali-pura, or the town of Patali, was called simply Patali, or corruptly Pattiali, on the invasion of the Musulmans: it is mentioned under that name in Mr. Dow's translation of Ferishta's history.

-- XVIII. On the Chronology of the Hindus, by Captain Francis Wilford

Highlights:

[Diodor. Sic. lib. XVII. c. 91. Arrian also, &c.] In 328 B.C., Porus's No Name nephew fled to Nanda, the king of the Gangaridae.

[Mudra-rachasa] Chandra-dasa, a petty king of Vicatpalli, disguised himself as a monk, took the name Suvidha, and fled to the country of Nanda. Is he supposed to be the same as Chandragupta? We hear nothing more of him.

[Mudra-rachasa] Nanda's body is taken over by "an unfortunate dethroned king" with No Name, whose practically lifeless body is tracked down and killed by unknown persons [Nanda's Minister?].

[Mudra-rachasa] Nanda's No Name Minister assassinated Nanda's body that had been taken over by the "unfortunate dethroned king" who is now "dead" for the second time, and places one of Nanda's sons on the throne. But when Nanda's No Name son finds out that the Minister killed his father, whose body had been taken over by the "unfortunate dethroned king", he had the Minister killed. The No Name Son of Nanda ruled the kingdom with seven brothers, but excluded his brother Chandragupta because he was born of a base woman from a tribe called "Mura". Chandragupta was also called "Mura/Maurya", because his mother. Chandragupta was at the same time the son of Nanda, and also the son of a barber. His brothers offered him an allowance instead of joint-kingship, and when he refused, they decided to kill him, or not. Chandragupta fled, then returned, and was in or near the palace when Porus's No Name nephew fled to Palibothra in 328 B.C., the year that Nanda was assassinated. In 327 B.C. Alexander camped on the Hyphasis, and it was then that Chandragupta visited his camp and said something that made Alexander want to kill him, after which Chandragupta fled home again. The eight Nanda brothers ruled for 12 years, until 315 B.C., when Chanacya put the brothers to death and made Chandragupta king. But Arabian writers, "according to the Nubian geographer," say that Chandragupta was defeated and killed by Alexander after Alexander crossed the Ganges.

[The Cumarica-chanda] Chanacya was disturbed after he killed the eight Nanda brothers, andwent to the Sucla-Thirta on the bank of the Narmada to be purified. There he was told to sail on a river in a boat with white sails, which if they turned black, would relieve him of his sins. This happened, so he set the boat adrift along with his sins into the sea. This happened 3,310 years after the Cali-yuga which is 210 A.D. "After three thousand and one hundred years of the Cali-yuga are elapsed (or in 3101) will appear king Saca (or Salivahana) to remove wretchedness from the world. The first year of Christ answers to 3101 of the Cali-yuga, and we may thus correct the above passage: Of the Caliyuga, 3100 save 300 and 10 years being elapsed (or 2790), then will Chanacya go to the Suclatirtha."

[The Agni-Purana] The Agni-Purana tells the same story a little differently. At an assembly of gods Indra said a Crashagni was the only thing that would get rid of Chanacya's sins. A Carshagni is when you cover the body with cowdung and set it on fire. A friendly crow overhead the gods talking, and flew to Chanacya to tell him. Chanacya then performed the ceremony, and "went to heaven." The gods then punished the crow for her "indiscretion." The Agni-Purana confirmed that this happened 312 years before the first year of the reign of Saca or Salivahana, which is 310 or 312 years before Christ, either 3 or 5 years after the murders of the Nanda brothers.

[Source Unknown] Soon after, Chandragupta made himself master of India and drove the Greeks out of the Punjab. "Tradition" says he built a city in the Deccan called "Chandragupta". Major Mackenzie "found" this city below Sri-Salam, or Purwutum, on the bank of the Crishna, even though there's nothing there but ruins. Why is why the inhabitants of the Deccan are so acquainted with the history of Chandragupta, because there's nothing left there to tell them anything. The author of the Mudra-Rakshasa was from the Deccan. Seleucus entered India at the head of an army, but found Chandragupta there, and being worried about the power of Antigonus, he made peace with Chandragupta, who gave him 50 elephants, and "a marriage took place to cement their relationship." Chandragupta is said to have been "very young" when he visited Alexander, and thus could have no marriageable daughter at the time of his treaty with Seleucus. This treaty happened in 302 B.C., which is 25 years after he visited Alexander; therefore the daughter must have been Seleucus's own daughter. It is supposed that Chandragupta had a large body of Greek troops in his service after that.

The accession of Chandragupta to the throne, and more particularly the famous expiation of Chanacya, after the massacre of the Sumalyas, is a famous era in the Chronology of the Hindus; and both may be easily ascertained from the Puranas, and also from the historians of Alexander. In the year 328 B.C. that conqueror defeated Porus; and as he advanced* [Diodor. Sic. lib. XVII. c. 91. Arrian also, &c.] the son of the brother of that prince, a petty king in the eastern parts of the Panjab, fled at his approach, and went to the king of the Gangaridae, who was at that time king Nanda of the Puranas. In the Mudra-rachasa, a dramatic poem, and by no means a rare book, notice is taken of this circumstance. There was, says the author, a petty king of Vicatpalli, beyond the Vindhyan mountains, called Chandra-dasa, who, having been deprived of his kingdom by the Yavanas, or Greeks, left his native country, and assuming the garb of a penitent, with the name of Suvidha, came to the metropolis of the emperor Nanda, who had been dangerously ill for some time. He seemingly recovered; but his mind and intellects were strangely affected. It was supposed that he was really dead, but that his body was re-animated by the soul of some enchanter, who had left his own body in the charge of a trusty friend. Search was made immediately, and they found the body of the unfortunate dethroned king, lying as if dead, and watched by two disciples, on the banks of the Ganges. They concluded that he was the enchanter, burned his body, and flung his two guardians into the Ganges. Perhaps the unfortunate man was sick, and in a state of lethargy, or otherwise intoxicated. Then the prince's minister assassinated the old king soon after, and placed one of his sons upon the throne, but retained the whole power in his own hands. This, however, did not last long; for the young king, disliking his own situation, and having been informed that the minister was the murderer of his royal father, had him apprehended, and put to a most cruel death. After this, the young king shared the imperial power with seven of his brothers; but Chandragupta was excluded, being born of a base woman. They agreed, however, to give him a handsome allowance, which he refused with indignation; and from that moment his eight brothers resolved upon his destruction. Chandragupta fled to distant countries, but was at last seemingly reconciled to them and lived in the metropolis; at least it appears that he did so, for he is represented as being in, or near, the imperial palace at the time of the revolution, which took place twelve years after Porus's relation made his escape to Palibothra in the year 328 B.C. and in the latter end of it. Nanda was then assassinated in that year; and in the following, or 327 B.C., Alexander encamped on the banks of the Hyphasis. It was then that Chandragupta visited that conqueror's camp; and, by his loquacity and freedom of speech, so much offended him, that he would have put Chandragupta to death if he had not made a precipitate retreat, according to Justin* [Lib. xv. c, 4.]. The eight brothers ruled conjointly twelve years, or till 315 years B.C., when Chandragupta was raised to the throne by the intrigues of a wicked and revengeful priest called Chanacya. It was Chandragupta and Chanacy, who put the imperial family to death; and it was Chandragupta who was said to be the spurious offspring of a barber, because his mother, who was certainly of a low tribe, was called Mura, and her son, of course, Maurya in a derivative from, which last signifies also the offspring of a barber; and it seems that Chandragupta went by that name, particularly in the west; for he is known to Arabian writers by the name of Mur, according to the Nubian geographer, who says that he was defeated and killed by Alexander; for these authors supposed that this conqueror crossed the Ganges; and it is also the opinion of some ancient historians in the west.

In the Cumarica-chanda, it is said, that it was the wicked Chanacya who caused the eight royal brothers to be murdered; and it is added, that Chanacya, after his paroxism of revengeful rage was over, was exceedingly troubled in his mind, and so much stung with remorse for his crime, and the effusion of human blood, which took place in consequence of it, that he withdrew to the Sucla-Tirtha, a famous place of worship near the sea on the bank of the Narmada, and seven coss to the west of Baroche, to get himself purified. There, having gone through a most severe course of religious austerities and expiatory ceremonies, he was directed to sail upon the river in a boat with white sails, which, if they turned black, would be to him a sure sign of the remission of his sins; the blackness of which would attach itself to the sails. It happened so, and he joyfully sent the boat adrift, with his sins, into the sea.

This ceremony, or another very similar to it, (for the expense of a boat would be too great), is performed to this day at the Sucla-Tirtha; but, instead of a boat, they use a common earthen pot, in which they light a lamp, and send it adrift with the accumulated load of their sins.

In the 63d section of the Agni-purana, this expiation is represented in a different manner. One day, says the author, as the gods, with holy men, were assembled in the presence of Indra, the sovereign lord of heaven, and as they were conversing on various subjects, some took notice of the abominable conduct of Chanacya, of the atrocity and heinousness of his crimes. Great was the concern and affliction of the celestial court on the occasion; and the heavenly monarch observed, that it was hardly possible that they should ever be expiated.

One of the assembly took the liberty to ask him, as it was still possible, what mode of expiation was requisite in the present case? and Indra answered, the Carshagni. There was present a crow, who, from her friendly disposition, was surnamed Mitra Caca: she flew immediately to Chanacya, and imparted the welcome news to him. He had applied in vain to the most learned divines; but they uniformly answered him, that his crime was of such a nature, that no mode of expiation for it could be found in the ritual. Chanacya immediately performed the Carshagni, and went to heaven. But the friendly crow was punished for her indiscretion: she was thenceforth, with all her tribe, forbidden to ascend to heaven; and they were doomed on earth to live upon carrion.

The Carshagni consists in covering the whole body with a thick coat of cow-dung, which, when dry, is set on fire. This mode of expiation, in desperate cases, was unknown before; but was occasionally performed afterwards, and particularly by the famous Sancaracharya. It seems that Chandragupta, after he was firmly seated on the imperial throne, accompanied Chanacya to the Suclatirtha, in order to get himself purified also.

This happened, according to the Cumarica-chanda, after 300 and 10 and 3000 years of the Cali-yuga were elapsed, which would place this event 210 years after Christ. The fondness of the Hindus for quaint and obscure expressions, is the cause of many mistakes. But the ruling epocha of this paragraph is the following: "After three thousand and one hundred years of the Cali-yuga are elapsed (or in 3101) will appear king Saca (or Salivahana) to remove wretchedness from the world. The first year of Christ answers to 3101 of the Cali-yuga, and we may thus correct the above passage: "Of the Caliyuga, 3100 save 300 and 10 years being elapsed (or 2790), then will Chanacya go to the Suclatirtha."

This is also confirmed in the 63d and last section of the Agni-purana, in which the expiation of Chanacya is placed 312 years before the first year of the reign of Saca or Salivahana, but not of his era. This places this famous expiation 310, or 312 years before Christ, either three or five years after the massacre of the imperial family.

My Pandit, who is a native of that country, informs me, that Chanacya's crimes, repentance, and atonement, are the subject of many pretty legendary tales, in verse, current in the country; part of some he repeated to me.

Soon after, Chandragupta made himself master of the greatest part of India, and drove the Greeks out of the Punjab. Tradition says, that he built a city in the Deccan, which he called after his own name. It was lately found by the industrious and active Major Mackenzie, who says that it was situated a little below Sri-Salam, or Purwutum, on the bank of the Crishna; but nothing of it remains, except the ruins. This accounts for the inhabitants of the Deccan being so well acquainted with the history of Chandragupta. The authors of the Mudra- Rakshasa, and its commentary, were natives of that country.

In the mean time, Seleucus, ill brooking the loss of his possessions in India, resolved to wage war, in order to recover them, and accordingly entered India at the head of an army; but finding Chandragupta ready to receive him, and being at the same time uneasy at the increasing power of Antigonus and his son, he made peace with the emperor of India, relinquished his conquests, and renounced every claim to them. Chandragupta made him a present of 50 elephants; and, in order to cement their friendship more strongly, an alliance by marriage took place between them, according to Strabo, who does not say in what manner it was effected. It is not likely, however, that Seleucus should marry an Indian princess; besides, Chandragupta, who was very young when he visited Alexander's camp, could have no marriageable daughter at that time. It is more probable, that Seleucus gave him his natural daughter, born in Persia. From that time, I suppose, Chandragupta had constantly a large body of Grecian troops in his service, as mentioned in the Mudra-Racshasa.

It appears, that this affinity between Seleucus and Chandragupta took place in the year 302 B.C. at least the treaty of peace was concluded in that year. Chandragupta reigned four-and-twenty years; and of course died 292 years before our era.

-- Essay III. Of the Kings of Magadha; their Chronology, by Captain Wilford, Asiatic Researches, Volume 9, 1809. pgs. 94-100.

Somadeva was an 11th century CE writer from Kashmir. He was the author of a famous compendium of Indian legends, fairy tales and folk tales -- the Kathasaritsagara.The Kathasaritsagara ("Ocean of the Streams of Stories") is a famous 11th-century collection of Indian legends, fairy tales and folk tales as retold in Sanskrit by the Shaivite Somadeva.

Kathasaritsagara contains multiple layers of story within a story and is said to have been adopted from Gunadhya's Brhatkatha, which was written in a poorly-understood language known as Paisaci.

The work is no longer extant but several later adaptations still exist — the Kathasaritsagara, Bṛhatkathamanjari and Brhatkathaslokasamgraha. However, none of these recensions necessarily derives directly from Gunadhya, and each may have intermediate versions. Scholars compare Gunadhya with Vyasa and Valmiki even though he did not write the now long-lost Bṛhatkatha in Sanskrit. Presently available are its two Sanskrit recensions, the Brhatkathamanjari by Ksemendra and the Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva.

-- Kathasaritsagara, by Wikipedia

Not much is known about him except that his father's name was Rama and he composed his work (probably during the years 1063-81 CE) for the entertainment of the queen Suryamati, a princess of Jalandhara and wife of King Ananta of Kashmir. The queen was quite distraught as it was a time when the political situation in Kashmir was 'one of discontent, intrigue, bloodshed and despair'.

-- Somadeva, by Wikipedia

Our knowledge of Civil Asiatic History (I always except that of the Hebrews) exhibits a short evening twilight in the venerable introduction to the first book of Moses, followed by a gloomy night, in which different watches are faintly discernible, and at length we see a dawn succeeded by a sunrise more or less early, according to the diversity of regions. That no Hindu nation but the Cashmirians, have left us regular histories in their ancient language, we must ever lament; but from the Sanscrit [Sanskrit] literature, which our country has the honour of having unveiled, we may still collect some rays of historical truth, though time and a series of revolutions have obscured that light which we might reasonably have expected from so diligent and ingenious a people. The numerous Puranas and Itihasas, or poems mythological and heroic, are completely in our powers and from them we may recover some disfigured but valuable pictures of ancient manners and governments; while the popular tales of the Hindus, in prose and in verse, contain fragments of history; and even in their dramas we may find as many real characters and events as a future age might find in our own plays, if all histories of England were, like those of India, to be irrecoverably lost. For example: A most beautiful poem by Somadeva, comprising a very long chain of instinctive and agreeable stories, begins with the famed revolution at Pataliputra, by the murder of king Nanda with his eight sons, and the usurpation of Chandragupta; and the same revolution is the subject of a tragedy in Sanscrit [Sanskrit], entitled, the Coronation of Chandra, the abbreviated name of that able and adventurous usurper.

From these once concealed, but now accessible, compositions, we are enabled to exhibit a more accurate sketch of old Indian history than the world has yet seen, especially with the aid of well attested observations on the places of the colures....

I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for though it could not have been Prayaga, where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja, which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks; nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erannoboas, which the accurate M. D'Anville had pronounced to be the Yamuna; but this only difficulty was removed, when I found in a classical Sanscrit book, near 2000 years old, that Hiranyabahu, or golden armed, which the Greeks changed into Erannoboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona itself; though Megasthenes, from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately. This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandracottus the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes; and was no other than that very Sandracottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator...

-- Discourse X. Delivered February 28, 1793, P. 192, Excerpt from "Discourses Delivered Before the Asiatic Society: And Miscellaneous Papers, on The Religion, Poetry, Literature, Etc. of the Nations of India", by Sir William Jones

Written by: Vishakhadatta

Characters: Chandragupta Maurya; Chanakya; Rakshasa; Malayketu, son of Parvataka; Parvatak; Vaidhorak; Seleucus I Nicator; Durdhara; Ambhi Kumar; Helena; Bhadraketu; Chandandasa; Jeevsidhhi

Original language: Sanskrit

Genre: Indian classical drama

Setting: Pataliputra, 3rd century BCE

Vishakhadatta was an Indian Sanskrit poet and playwright. Although Vishakhadatta furnishes the names of his father and grandfather as Maharaja Bhaskaradatta and Maharaja Vateshvaradatta in his political drama Mudraraksasa, we know little else about him. Only two of his plays, the Mudraraksasa and the Devichandraguptam are known to us. His period is not certain...

Mudraraksasa ("Rakshasa's Ring") is Vishakhadatta’s only surviving play, although there exist fragments of another work ascribed to him. Vishakhadatta has stressed upon historical facts in the Mudrarakshasa, a play dealing with the time of the Maurya Dynasty....

Stylistically he stands a little apart from other dramatists. A proper literary education is clearly no way lacking, and in formal terms, he operates within the normal conventions of Sanskrit literature, but one does not feel that he cultivates these conventions very enthusiastically for their own sake.... Vishakhadatta’s prose passages in particular often have a certain stiffness compared to the supple idiom of both Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti ... his style includes towards the principle of “more matter and less art.”... [He was a man] of action ...

The name Vishakhadatta is also given as Vishakhadeva from which Ranajit Pal concludes that his name may have been Devadatta which, according to him, was a name of both Ashoka and Chandragupta.

-- Vishakhadatta, by Wikipedia

Also in the twelfth century, Visakha Datta, son of King Prithou Rai, published the important drama Mudra Rakchasa or the Minister's Ring, in seven acts, one of the best plays in the Indian repertoire; it was commented on by Vateswara Misra, priest of Mithila, and by Govhasena. We see the Brahman Tchanakya, after having assassinated Nanda, tyrant of Pataliputra, give the throne, following a host of complicated incidents, to Prince Tchandragoupta.

-- Critical Essay on Indian Literature and Sanskrit Studies, with bibliographical notes, by Alfred Philibert Soupé

The Mudrarakshasa (मुद्राराक्षस, IAST: Mudrārākṣasa, transl. 'The Signet of the Minister') is a Sanskrit-language play by Vishakhadatta that narrates the ascent of the king Chandragupta Maurya (r. c. 324 – c. 297 BCE) to power in India. The play is an example of creative writing, but not entirely fictional.[1] It is dated variously from the late 4th century[2] to the 8th century CE.[3]

Characters

• Chandragupta Maurya, one of the protagonists

• Chanakya, one of the protagonists

• Rakshasa, the main antagonist

• Malayketu, the son of Parvataka and one of the henchmen

• Parvatak, a greedy king who firstly supported Chandragupta but later changed his preference to Dhana Nanda

• Vaidhorak

• Durdhara, wife of Chandragupta Maurya

• Bhadraketu

• Chandandasa

• Jeevsidhhi

Adaptations

There is a Tamil version based on the Sanskrit play[4] and Keshavlal Dhruv translated the original into Gujarati as Mel ni Mudrika (1889).

The later episodes of the TV series Chanakya were based mostly on the Mudrarakshasa.

Feature film

A film in Sanskrit was made in 2006 by Dr Manish Mokshagundam, using the same plot as the play but in a modern setting.[5]

Editions

• Antonio Marazzi (1871), Teatro scelto indiano tr. dal sanscrito (Italian translation), D. Salvi e c.

• Kashinath Trimbak Telang (1884), Mudrarakshasa With the Commentary of Dhundiraja (written in 1713 CE) edited with Sanskrit text, critical and explanatory notes, introduction and various readings, Tukârâm Javajī. Second edition 1893, Fifth edition 1915. Sixth edition 1918, reprinted 1976 and by Motilal Banarsidass, 2000.

• Ludwig Fritze (1886), Mudrarakschasa: oder, Des kanzlers siegelring (German translation), P. Reclam jun.

• Victor Henry (1888), Le sceau de Râkchasa: (Moudrârâkchasa) drame sanscrit en sept actes et un prologue (French translation), Maisonneuve & C. Leclerc

• Moreshvar Ramchandra Kāle (1900), The Mudrárákshasa: with the commentary of Dhundirája, son of Lakshmana (and a complete English translation)

• Hillebrandt, Alfred (1912). Mudrarakshasa Part-i.

• K. H. Dhruva (1923), Mudrārākshasa or the signet ring: a Sanskrit drama in seven acts by Viśākhadatta (with complete English translation) (2 ed.), Poona Oriental Series (Volume 25), archived from the original on 23 June 2010, retrieved 21 May 2010. Reprint 2004, ISBN 81-8220-009-1 First edition 1900

• Vasudeva Abhyankar Shastri; Kashinath Vasudeva Abhyanker (1916), Mudraraksasam: a complete text; with exhaustive, critical grammatical and explanatory notes, complete translation, and introduction, Ahmedabad

• Ananta Paṇḍita (1945), Dasharatha Sharma (critical introduction) (ed.), Mudrarakshasapurvasamkathanaka of Anantasarman (with an anonymous prose narrative), Bikaner: Anup Sanskrit Library

• P. Lal (1964), Great Sanskrit Plays, in Modern Translation, New Directions Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8112-0079-0

• J. A. B. van Buitenen (1968), Two plays of ancient India: The little clay cart, The minister's seal, Columbia University Press Review

• Sri Nelaturi Ramadasayyangaar (1972), Mudra Rakshasam, Andhra Pradesh Sahitya Academy (In Telugu script, with Telugu introduction and commentary) Another version

• Michael Coulson (2005), Rākṣasa's ring (translation), NYU Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-1661-8. Originally published as part of Three Sanskrit plays (1981, Penguin Classics).

References

Citations

1. Romila Thapar (2013). The Past Before Us. Harvard University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-674-72652-9.

2. Manohar Laxman Varadpande (1 September 2005). History Of Indian Theatre. Abhinav Publications. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-81-7017-430-1. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

3. Upinder Singh (1 September 2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

4. Viśākhadatta; S. M. Natesa Sastri (1885), Mudrarakshasam: A tale in Tamil founded on the Sanskrit drama, Madras School Book and Vernacular Literature Society

5. Film promo

Sources

• Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3