Librarian Study Notes on the Taxonomy of River and Mountain Names, as derived from "On the ancient Geography of India"

by Lieut. Col. F. Wilford

1822

Highlights of the Whole Essay as it Pertains to Palibothra/Pataliputra:

A FEW years after my arrival in India, I began to study the ancient history, and geography of that country; and of course, endeavoured to procure some regular works on the subject: the attempt proved vain, though I spared neither trouble, nor money, and I had given up every hope, when, most unexpectedly, and through mere chance, several geographical tracts in Sanscrit, fell into my hands....

In some of the Puranas, there is a section called the Bhuvana-cosa, a magazine, or Collection of mansions: but these are entirely mythological, and beneath our notice.

Besides those in the Puranas, there are other geographical tracts, to several of which is given the title of Cshetra-samasa, or collection of countries; one is entirely mythological, and is highly esteemed by the Jainas; another in my possession, is entirely geographical, and is a most valuable work.

There is also the Trai-locya-derpana, or mirror of the three worlds: but it is wholly mythological, and written in the spoken dialects of the countries about Muttra. St. Patrick is supposed to have written such a book, which is entitled de tribus Habitaculis, and this was also entirely mythological.

There are also lists of countries, rivers and mountains, in several Puranas, and other books; but they are of little or no use, being mere lists of names, without any explanation whatever. They are very incorrectly written, and the context can be of no service, in correcting the bad spelling of proper names. These in general are called Desamala, or garlands of countries; and are of great antiquity: they appear to have been known to Megasthenes, and afterwards to Pliny....

Real geographical treatises do exist: but they are very scarce, and the owners unwilling, either to part with them, or to allow any copy to be made, particularly for strangers.... Seven of them have come to my knowledge, three of which are in my possession. The two oldest are the Munja-prati-desa-vyavastha, or an account of various countries, written by Raja Munja, in the latter end of the ninth century: it was revised and improved by Raja Bhoja his nephew, in the beginning of the tenth, it is supposed; and this new edition was published under the name of Bhoja-prati-desa-vyavastha. These two treatises, which are voluminous, particularly the latter, are still to be found, in Gujarat, as I was repeatedly assured, by a most respectable Pandit, a native of that country, who died some years ago, in my service. I then applied to the late Mr. Duncan, Governor of Bombay, to procure those two geographical tracts, but in vain: his enquiries however confirmed their existence. These two are not mentioned in any Sanscrit book, that I ever saw. The next geographical treatise, is that written by order of the famous Buccaraya or Bucca-sinha, who ruled in the peninsula in the year of Vicramaditya, 1341, answering to the year 1285 of our era. It is mentioned in the commentary on the geography of the Maha-bharata, and it is said, that he wrote an account of the 310 Rajaships of India, and Palibothra is mentioned in it. I suspect that this is the geographical treatise called Bhuvana-sagara, or sea of mansions, in the Dekhin....

The fourth is a commentary on the geography of the Maha-bharat, written by order of the Raja of Paulastya in the peninsula, by a Pandit, who resided in Bengal, in the time of Hussein-shah, who began his reign in the year 1489[???]. It is a voluminous work, most curious, and interesting. It is in my possession, except a small portion towards the end, and which I hope to be able to procure. Palibothra is mentioned in it.

The fifth is the Vicrama-sagara: the author of it is unknown here: however it is often mentioned in the Cshetra-samasa, which, according to the author himself, is chiefly taken from the Vicrama-sagara. It is said to exist still in the peninsula, and it existed in Bengal, in the year 1648. It is considered as a very valuable work, and Palibothra is particularly mentioned in it, according to the author of the Cshetra-samasa. I have only seventeen leaves of this work, and they are certainly interesting. Some suppose that it is as old as the time of Bucca-raya [1356-1377 CE] , that it was written by his order, and that the author was a native of the Dekhin.

But the author could not be a native of that country, otherwise, he would have given a better description of it; for his account of the country about the Sahyadri mountains, of which an extract is to be found in the Cshetra-samasa, is quite unsatisfactory, and obviously erroneous even in the general outlines....

The sixth is called the Bhuvana-cosa, and is declared to be a section of the Bhavishya-purana. If so, it has been revised, and many additions have been made to it, and very properly, for in its original state, it was a most contemptible performance. As the author mentions the emperor Selim-Shah, who died in the year 1552, he is of course posterior to him. It is a valuable work. Additions are always incorporated into the context in India, most generally without reference to any authority; and it was formerly so with us; but this is no disparagement in a geographical treatise: for towns, and countries do not disappear, like historical facts, without leaving some vestiges behind. I have only the fourth part of it, which contains the Gangetick provinces. The first copy that I saw, contained only the half of what is now in my possession; but it is exactly the same with it, only that some Pandit, a native of Benares, has introduced a very inaccurate account of the rebellion of Chaityan-Sinha, commonly called Cheyt-Sing, in the year, I believe 1781: but the style is different.

The seventh is the Cshetra-samasa already mentioned, and which was written by order of Bijjala, the last Raja of Patna, who died in the year 1648. Though a modern work, yet it is nevertheless a valuable and interesting performance. It contains only the Gangetick provinces and some parts of the peninsula, such as Trichina-vali, &c. The death of the Raja prevented his Pandit Jagganmohun from finishing it, as it was intended, for the information of his children.

The last chapter, which was originally a detached work, is an account of Patali-putra, and of Pali-bhata as it is called there, and it consists of forty-seven leaves. This was written previously to the geographical treatise, and it gives an account, geographical, historical, and also mythological of these two cities, which were contiguous to each other. It gives also a short history of the Raja's family, and of his ancestors, and on that account only was this small tract originally undertaken. We may of course reasonably suppose that it was written at least 170 years ago.

The writer informs us that, long after the death of Raja Bijjala or Baijjala, he was earnestly requested by his friends, to complete the work, or at least to arrange the materials he had already collected in some order, and to publish it, even in that state. He complied with their request; but it must have been long after the death of the king, for he mentions Pondichery; saying, that it was inhabited by Firangs, and had three pretty temples dedicated to the God of the Firanga, Feringies or French, who did not, I believe, settle there before the year 1674. He takes notice also of Mandarajya, or Madras.

The author acts with the utmost candour, and modesty, saying, as I have written the Prabhoda-chandrica after the "Pracriya-caumudi (that is to say from, and after the manner of that book) so I have written this work after the Vicrama-sagara, and also from enquiries, from respectable well informed people, and from what, I may have seen myself."

In the Cshetra-samasa, two other geographical tracts are mentioned; the first is the Dacsha-chandaca, and the other is called Desa-vali, which, according to the author’s account, seem to be valuable works. There is also a small geographical treatise called Crita-dhara-vali, by Rameswara, about 200 years old, it is supposed. I have only eighty leaves of it, and it contains some very interesting particulars.... Two copies were possessed by Dr. Buchanan, and I have also procured a few others. All these are most contemptible lists of names, badly spelt, without any explanation whatever, and they differ materially the one from the other. However there is really a valuable copy of it, in the Tara-tantra, and published lately by the Rev. Mr. Ward [William Ward, b. 1769 Derby]. I have also another list of countries with proper remarks, from the Galava-tantra[???], in which there are several most valuable hints. However these two lists must be used cautiously, for there are also several mistakes.

This essay on the ancient geography of the Gangetick provinces, will consist of three sections.... Then occasionally, and collaterally will appear accounts, both historical and geographical of some of the principal towns, such as Palibothra and Patali-putra now Patna, for these two towns were close to each other, exactly like London and Westminister.

The former was once the metropolis of India; but at a very early period it was destroyed by the Ganges: an account of it is in great forwardness, and is nearly ready for the press. Its name in Sanscrit was Pali-bhatta, to be pronounced Pali-bhothra, or nearly so. Bali-gram near Bhagalpur, never was the metropolis of India; yet it was a very ancient city, and its history is very interesting. It was also destroyed by the Ganges....

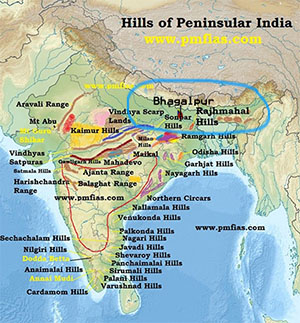

In the Cshetra-samasa the Carna-phulli [Karnaphuli/ Karnafuli/ Khawthlanguipui: Wiki] or Chatganh [Chittagong: Wiki] river, is said to come from the Jayadri or mountains of victory, and the Nabhi or Naf [Naf: Wiki] river from the Suvarda, or golden mountains...

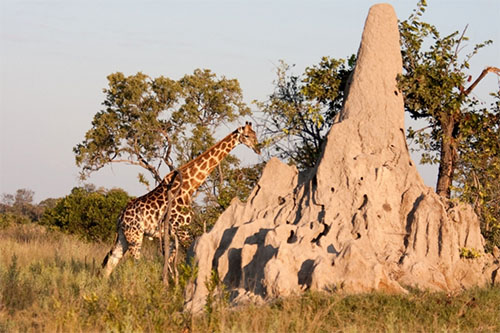

[T]he mountains and forests of Jhar-chand are called, in the Peutingerian tables, the Lymodus mountains, abounding with elephants, and placed there to the south of the Ganges. They really were in the country of Magadh or Magd, as generally pronounced, and which was also the name of Patna and of south Bahar....

The royal road from the Indus to Palibothra crossed this river [Calindi] at a place called Calini-pacsha [Kalinipaxa], according to Megasthenes, and now probably Khoda-gunge; Calini-pacsha in Sanscrit signifies a place near the Calini....

The next is the Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], or red river: in the Puranas it is constantly called Sona, and I believe never otherwise. In the Amara cosa, and other tracts, I am told, it is called Hiranya-bahu, implying the golden arm, or branch of a river, or the golden canal or channel. These expressions imply an arm or branch of the Sona, which really forms two branches before it falls into the Ganges....

The epithet of golden does by no means imply that gold was found in its sands. It was so called, probably, on account of the influx of gold and wealth arising from the extensive trade carried on through it; for it was certainly a place of shelter for all the large trading boats during the stormy weather and the rainy season.

In the extracts from Megasthenes by Pliny and Arrian, the Sonus and Erannoboas appear either as two distinct rivers, or as two arms of the same river. Be this as it may, Arrian says that the Erannoboas was the third river in India, which is not true. But I suppose that Megasthenes meant only the Gangetick provinces: for he says that the Ganges was the first and largest. He mentions next the Commenasis or Sarayu, from the country of Commanh, as a very large river. The third large river is then the Erannoboas or river Sona[???].

Ptolemy, finding himself peculiarly embarrassed with regard to this river, and the metropolis of India situated on its banks, thought proper to suppress it entirely. Others have done the same under similar distressful circumstances. It is however well known to this day, under the denomination of Hiranya-baha, even to every school boy, in the Gangetick provinces, and in them there is no other river of that name...

Let us now proceed to the Sulacshni, or Chandravati, according to the Cshetra-samasa. It is now called the river Chandan, because it flows through the Van or groves of Chandra, in the spoken dialects Chandwan, or Chandan. In the maps it is called Goga, which should be written Cauca, because according to the above tract, it falls into the Ganges, at a place called Cucu, and in a derivative form Caucava, Caucwa, or Cauca. It flows a little to the eastward of Bhagalpur: but the place, originally so called, has been long ago swallowed up by the Ganges, along with the town of Bali-gram. In the Jina-vilas[???], it is called Aranya-baha[!!!], or the torrent from the wilderness, being really nothing more....

Then comes the Suvarna-recha [Subarnarekha/Swarnarekha: Wiki], or Hiranya-recha, that is to say the golden streak [Subarnarekha, meaning "streak of gold" found in the riverbed: Wiki]. It is called also in the Puranas, in the list of rivers, Suctimati, flowing from the Ricsha, or bear mountains. Its name signifies abounding with shells, in Sanscrit Sucti, Sancha, or Cambu....

The Damiadee[???] was first noticed by the Sansons in France, but was omitted since by every geographer, I believe, such as the Sieur Robert, the famous D’Anville, &c; but it was revived by Major Rennell, under the name of Dummody. I think its real name was Dhumyati, from a thin mist like smoke, arising from its bed. Several rivers in India are so named: thus the Hiranya-baha, or eastern branch of the Sona, is called Cujjhati, or Cuhi from Cuha, a mist hovering occasionally over its bed. As this branch of the Sona has disappeared, or nearly so, this fog is no longer to be seen. I think, this has been also the fate of the Dhumyati, which is now absorbed by the sands....

Let us now pass to the Brahma-putra [Brahmaputra: Wiki], or Brahmi-tanaya, that is to say the son of Brahma, or rather his efflux.

Brahma, in the course of his travels, riding upon a goose, passed by the hermitage of the sage Santanu, who was gone into the adjacent groves, and his wife, the beautiful and virtuous Amogha, was alone. Struck with her beauty he made proposals, which were rejected with indignation, and Amogha threatened to curse him.

Brahma, who was disguised like a holy mendicant, began to tremble and went away: however, before he turned round, his efflux fell to the ground at the door of the hermitage. The efflux is describe, as Hataca, like gold, Cara-hataca, radiant and shining like gold, which is the colour of Brahma; it is always in motion like quicksilver. On Santanu’s return Amogha did not fail to acquaint him with Brahma’s behaviour: he gave due praise to her virtue and resolution, but observed at the same time that with regard to a person of such a high rank as Brahma, who is the first of beings in the world, she might have complied with his wishes without any impropriety. This is no new idea; however Amogha reprobated this doctrine with indignation. I shall pass over how this efflux was conveyed into her womb by her husband. The Nile was also the efflux of Osiris, and probably the legend about it was equally obscene and filthy. In due time she was delivered of a fine boy amidst a vast quantity of water, and who was really the son of Brahma, and exactly like him. Then Santanu made a Cunda, or hole like a cup, and put the child and waters into it. The waters soon worked their way below to the depth of five Yojans, or forty miles nearly, and as far as Patal, or the infernal regions. This Cunda, or small circular pond, or lake, is called Brahmacunda, and the river issuing from it Brahma-putra, the son of Brahma....

There is little doubt but that the Soma or Sami is the Isamus of Strabo, the boundary of Menander's kingdom....

There are in Asama [Assam: Wiki] two rivers called Lohita [mythological river, actually part of the Brahmaputra: IndiaZone.com], and both are mentioned in the Matsya-purana, in the list of rivers; the Chacra-Lohita or greater Lohita, and the Cshudra-Lohita, or the lesser one. This last falls into the Brahma-putra near Yogi-gopa, and is noticed in the Bengal Atlas. The original name of the greater Lohita is Sama or Sam, and this is conformable to a passage in the Varaha-mihira-sanhita. The Sama was afterward called the red river, from the following circumstance. The famous Rama, with the title of Parasu or Parsu, having been ordered by his father to cut off his own mother’s head, through fear of the paternal curse was obliged to obey. With his bloody Parasu, or Parsu, or cimetar in one hand, and the bleeding head of his mother in the other, he appeared before his father who was surrounded by holy men, who were petrified with horror at this abominable sight. He then went to the Brahma-cunda to be expiated, his cimetar sticking fast to his hand all the way; he then washed it in the waters of the Sama, which became red and bloody, or Lohita. The cimetar then fell to the ground, and with it he cleft the adjacent mountains, and opened a passage for himself to the Cunda, and also for the waters of the Brahma-putra; he then flung the fatal instrument into the Cunda. The cleft is called to this day Prabhu-Cuthara, because it was made with a mighty Cuthara, or cimetar. This is obviously the legend of Perseus, and the Gorgon’s head....

The Carma-phulli, as I observed before, is called in the upper part of its course Dumbura, Dumura, or Dumriya: on its passing through the hills it assumes the name of Carma-phulli: but its original name is Bayuli or Bayula.* [Cshetra-samasa and Bhuvana-cosa.] In the Bhuvana-cosa it is declared that it flows through the country of Ari-rajya, or kingdom of Ari, where it assumes the name of Nabhi, according to the Cshetra-samasa, and is commonly called the Naf, and Teke-naf. This river is called in the Bhuvana-cosa, Hema, or golden river, probably because it comes from the golden mountains, styled Hema, Canchana, Canaca &c., which signify gold. In general all the rivers of this country are considered as branches of the Carma-phulli, some are actually so, others are so only in a mystical sense....

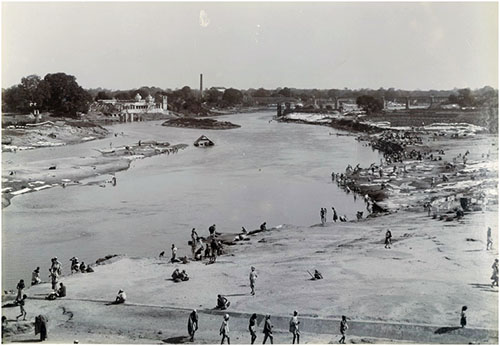

It is well known that the old site of Patali-putra, or Patna, has been entirely carried away by the Ganges, and in its room several sand banks were formed, and which are delineated in Major Rennell's map of the course of the Ganges with his usual accuracy. However Colonel Colebrooke [Robert Hyde Colebrooke], Surveyor General, having made a new survey of the river, found that these several sand banks were consolidated into an island about sixteen miles long, and which masks entirely the mouth of the Gandaci, nay it has forced it in an oblique direction about six miles below Patna, whilst in Major Rennell’s time it was due north from the N.W. corner of that town, and in sight of it.

The most ancient town of Bali-gur, or Balini-gur, close and opposite to Bhagal-pur, was entirely destroyed by the Ganges in the beginning of the thirteenth century, according to the Cshetra-samasa....

As the Caggar, or some river falling into it, is supposed by our ancient writers to have been also the boundary of the excursions of the gold making ants toward the east, I shall give an account of them...

The large ant of the size of a fox, or of a Hyrcanian dog, is the Yuz of the Persians, in Sanscrit Chittraca-Vyaghra, or spotted tyger in Hindi Chitta, which denomination has some affinity with Cheunta, or Chyonta, a large ant. This has been, in my opinion, the cause of this ridiculous and foolish mistake of some of our ancient writers. The Yuz is thus described in the Ayin Acberi.(3) "This animal, who is remarkable for his provident and circumspect conduct, is an inhabitant of the wilds, and has three different places of resort. They feed in one place, rest in another, and sport in another, which is their most frequent resort. This is generally under the shade of a tree, the circuit of which they keep very clean, and enclose it with their dung. Their dung, in the Hindovee language, is called Akhir.”

Abul-Fazil, it is true, does not say positively that their dung, mixing with sand, becomes gold, and probably he did not believe it. However, when he says that this dung was called Akhir in Hindi, it implies the transmutation of the mixture into gold. Akhir is for Chir in the spoken dialects, from the Sanscrit Cshira; from this are derived the Arabic words Acsir, and El-acsir-Elixir is water, milk also, and a liquid in general. To effect this transmutation of bodies the Hindus have two powerful agents, one liquid called emphatically Cshir, or the water. The other is solid, and is called Mani, or the jewel; and this is our philosopher’s stone, generally called Spars a-mani, the jewel of wealth; Hiranya-mani, the golden jewel. There are really lumps of gold dust, consolidated together by some unknown substance, which was probably supposed to be the indurated dung of large birds.

These are to be met with in the N.W. of India, where gold dust is to be found. They contain much gold, it is said, and are sold by the weight.

On the ancient Geography of India, by Lieut. Col. F. Wilford, 1822

Various Names of the Brahma-putra

Brahma-putra, or Brahmi-tanaya, that is to say the son of Brahma, or rather his efflux.... Brahma, in the course of his travels, riding upon a goose, passed by the hermitage of the sage Santanu, who was gone into the adjacent groves, and his wife, the beautiful and virtuous Amogha, was alone. Struck with her beauty he made proposals, which were rejected with indignation, and Amogha threatened to curse him.

Brahma, who was disguised like a holy mendicant, began to tremble and went away: however, before he turned round, his efflux fell to the ground at the door of the hermitage. The efflux is describe, as Hataca, like gold, Cara-hataca, radiant and shining like gold, which is the colour of Brahma; it is always in motion like quicksilver....

In due time she was delivered of a fine boy amidst a vast quantity of water, and who was really the son of Brahma, and exactly like him. Then Santanu made a Cunda, or hole like a cup, and put the child and waters into it. The waters soon worked their way below to the depth of five Yojans, or forty miles nearly, and as far as Patal, or the infernal regions. This Cunda, or small circular pond, or lake, is called Brahmacunda, and the river issuing from it Brahma-putra, the son of Brahma....

In the Ambica-chanda it is said that the sun performs there his ablutions before he appears above the horizon. It is called Sadya-hrada, or the deep pool where the sun gets rid of his weariness, Sad or Sadi, after his fatiguing task. For this reason the Brahma-putra, which comes out of this pool, is called Gabhasti, or the river of the sun....

The Brahma-putra, is also called Hradini, as I observed in a former Essay on the Geography of the Puranas. This word, sometimes pronounced Hladni, signifies in Sanscrit a deep and large river, from Hrida, to be pronounced Hrada or nearly so, and from which comes Hradana and Hradini. In the list of rivers in the Padma-purana, it is called Hradya or Hradyan, and its mouth is called by Ptolemy the Airradon Ostium, or the mouth of the river Hradan: and according to him, another name for it was Antiboli, from a town of that name, called also by Pliny Antomela, in Sanscrit, Hasti-malla, in the spoken dialects Hatti-malla, now Feringy-bazar to the S.E. of Dhacca....

The trident of the lord of the world is certainly Vara-sula, Pra-sula, and Sri-sula, which are denominations implying excellence and power. The rock on which it stood was of course Vara-sila, Para-sila, and Sri-sila, or the most excellent, and blessed rock, and the river in which it stood was once so called probably, at first by favourite poets who sang the praises of Maha-deva and of his linga, not forgetting the rock on which it stood, nor the river in which it was situated, for we find the Brahma-putra called by European writers of the seventeenth century Persilis, and Sersilis, in the easternmost parts of Hindustan, and it is connected by them with the river Lacsha, or Lakya....

In the long lists of rivers in the Maha-bharat and Padma-purana, the Brahma-putra is called Anta-sila, or the river of the rock of our latter end; alluding to the above rock....

Ctesias mentions wild men living in the waters of the river Gaita in India in some part of its course, and from the context this was in the easternmost parts of that country. Gaita is perhaps for Khatai, another name, for the Brahma-putra, because it was supposed to come from the immense country of Khatai. Palladius, in his account of the Brahmens says, that there were in the Ganges dragons seventy cubits long, besides an animal called Odonto who could swallow a whole elephant and was so much dreaded that no body durst cross that river, only at the time of the year when the Brahmens visited their wives who lived on the other side, for during that season the monster was never seen. Palladius supposes this river to be the Ganges, which seems to have been the limit of his geographical knowledge towards the east, but it was more probably the Brahma-putra. The denominations of Par-silis or Ser-silis are now unknown in India, as well as that of Khamdan mentioned by El Edrissi, who says that it is a large river which comes from China and falls into the Ganges. There is no doubt however that at an early period it was current in India, for it is the Cainas of Pliny, and the Doanas or Daonas of Ptolemy. These two words being joined together make Cain-Doanas. In Sanscrit Cayan-dhu, and in a derivative form Cayan-dhava, or Cayan-dhau, Cayan-dhauni, or dhauna and Cayan-dhuni, would signify the river of Caya or Brahma, and of course it is another name for the Brahma-putra, implying exactly the same thing....

This country of Cayan or Cayan-dhu is mentioned by M. Polo, with a river called Brius, which is the Brahma-putra....

To the west of Carayan and of the Corrun hills was the country called Cayndu by M. Polo, and which was bounded towards the west by the river Brius. This is the Brahma-putra, which is often styled, if not called, the river Biryya, because it is the efflux of Brahma, and this word is always pronounced in the east Birjja....

This Brahma-cunda, from which issues the Brahma-putra, is the same which is called Chiamay by De Barros, and other Portuguese writers. De Barros calls the Brahma-putra the Caor river, and says, that it comes from the lake Chiamay, and from thence it goes to the town of Caor after which it was denominated, thence to Sirote, to Camotay, and afterwards into the sea....

The Brahma, or Brahmi river, another name for the Brahma-putra, is called Caya, one of the names of Brahma; hence the river of Ava, supposed to spring from the above lake, is called Cay-pumo, or the Burman Brahmu-putra; for the Burman country is also called Pummay according to Dr. Buchanan, and Puma-hang by the four Chinese merchants mentioned by Du Halde....

The Pauranics, in their geographical diagrams, make the Hradini, or Brahma-putra, with the Pavani or Ava river, to flow toward the S.E. The source of the eastern branch of the Doanas, or Brahma-putra, is really at the Brahma-cunda...

Pliny calls the river of Ava, Pumas or Puman, in the objective case; and says that many nations in that part of the country were called in general Brachmanoe, it should be Barmanoe. One is particularly noticed by him, "the Maccocalingoe, with two rivers called Pumas, and Cainas; both navigable, but the Cainas alone, says he, fall into the Ganges." It is therefore the Cayana, or Brahma-putra....

Ptolemy says that the easternmost branch of the Ganges was called Antibole[???] at Airradon. This last is from the Sanscrit Hradana, and is the name of the Brahma-putra.

-- On the ancient Geography of India, by Lieut. Col. F. Wilford

[In the Cshetra-samasa, the "Carna-phulli/Chatganh" river is said to come from "Jayadri/mountains-of-victory", and the "Nabhi/Naf" river from the "Suvarda/golden-mountains."]

In the Cshetra-samasa the Carna-phulli [Karnaphuli/Karnafuli/Khawthlanguipui: Wiki] or Chatganh [Chittagong: Wiki] river, is said to come from the Jayadri or mountains of victory, and the Nabhi or Naf [Naf: Wiki] river from the Suvarda, or golden mountains...

[Called "Calindi" river because it comes from a hilly country named "Calinda".]

Blue Yamuna [Yamuna/Jamuna: Wiki] or Calindi [Kalindi/"Yamuna {Kalindi} is one of the ashtabharya {8 wives} Lord Krishna": Wiki], the daughter of the sun, the sister of the last Manu, and also of Yama or Samana, our Pluto or Summanus. Her relationship with the lesser Calindi, or Calini, is not noticed by the Pauranics, though otherwise well known. In the spoken dialects it is called Jamuna, Jumna, and Jubuna particularly in Bengal. It is called Diamuna by Ptolemy, Jomanes by Pliny, and Jobares by Arrian, probably for Jobanes or Jubuna. It is called Calindi because it has its source in the hilly country of Calinda, called Culinda in the Geographical Commentaries on the Maha-bharata.[???] It is the Culindrine of Ptolemy from Culindan, a derivative from Culinda....

[Called "Triveni" because three rivers meet there, except that there are really only two.]

The confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna at Prayaga [Allahabad/Prayagraj/Ilahabad: Wiki] is called Triveni by the Pauranics; because three rivers are supposed to meet there; but the third is by no means obvious to the sight....

[Called "Triveni" because, like braided hair, three rivers flow together, but don't mix.]

These three rivers flow then together, as far as the southern Triveni in Bengal, forming the Triveni, or the three plaited locks: for their waters do not mix, but keep distinct all the way. The waters of the Yamuna are blue, those of the Sarasvati white, and the Ganges is of a muddy yellowish colour....

[Called "Tamasa/Dark-river", because its surrounded by dense forests.]

The Tamasa, or dark river, from its being skirted, at least formerly, with gloomy forests, is called Tonsa or Tonso in the spoken dialects and by Ptolemy Touso or Tousoa....

[Called "Parnasa" because there is a fort at its confluence with the Ganges called "Parnasa"]

It is occasionally called Parnasa, as in the Vayu and* [Section of the earth.] Matsya-puranas; and at its confluence with the Ganges, there is a very ancient place, and fort called to this day Parnasa....

[Called "Carmmanasa" because contact with it causes one to lose good karma; called "Vindhya-maulica" because they are the original mountains of "Vindhya"; the country around it is called "dark" because the mountain insolently reared its head above the Himalaya; the ground it covers is called "Mauli" because the "Carmmanasa" comes from the country of "Mauli"; the "Omalis" of Megasthenes sounds like "Mauli," therefore it's declared to be the same; "Commenasis" of Megasthenes is declared to be "Sarayu", and called "Commenasis" because it comes from a country called "Comanh/Almora"; the "Cacuthis" of Megasthenes is declared to be "Puna-puna", called "Cacuthis" because it comes from a country called "Cicata;" called "Magadhi" by the Puranics because it comes from a country called "Cicata."]

The next river is the hateful Carmmanasa, so called, because, by the contact alone of its waters, we lose at once the fruit of all our good works. Its source is in that part of the Vindhya hills called in the Puranas Vindhya-maulica, which implies the heads, peaks or summits of the original mountains of Vindhya. This mountain presumed once to rear his head above that of Himalaya, and thus consigned it and the intermediate country to total darkness. One day Vindhya, perceiving the sage Agastya his spiritual guide, prostrated himself to the ground before him as usual, when the sage as a punishment for his insolence, ordered him to remain in that posture.... All the ground he covers with his huge frame is denominated Mauli, or the heads or peaks of Vindhya, and is declared to be the original Vindhya, which gives its name to the whole range, from sea to sea, and is supposed to extend from the Sona to the Tonsa. As the Carmmanasa comes from the country of Mauli, there is then a strong presumption, that it is the river Omalis of Megasthenes: thus the great river, which he calls Commenasis, is the Sarayu, and is so called, because it comes from the country of Comanh, or Almora. The river Cacuthis of the same author is the Puna-puna, and is so called because it flows through the country of Cicata. It is also called Magadhi by the Pauranics, for a similar reason. In this manner the Yamuna is also called Calindi, because it comes from the hilly country of Calinda...

[River "Mauli" called "Infected/Spoiled" because of Myth of Tri-Sancu; "Vindhya" mountains called "Rohita/Lohita/Red-and-Bloody" because of Myth of Tri-Sancu.]

The waters of the river Mauli were originally as pure, and beneficial to mankind, as those of any river in the country. However they were long after infected and spoiled through a most strange and unheard of circumstance, in consequence of which its present name was bestowed upon it.

Tri-sancu was a famous and powerful king, who lived at a very early period, and through religious austerities, and spells, presumed to ascend to heaven with his family. The gods, enraged at his insolence, opposed him, and he remains suspended half way with his head downwards. From his mouth issues a bloody saliva, of a most baneful nature. It falls on Vindhya, and gives to these mountains a reddish hue: hence they are called Rohita or Lohita, the red and bloody hills in the vicinity of Rotas....

[Called "Sona/red" in Puranas; called "Hiranyabahu/Golden arm" in Amara cosa.]

The Sona [Son/Sone: Wiki], or red river: in the Puranas it is constantly called Sona, and I believe never otherwise. In the Amara cosa, and other tracts, I am told, it is called Hiranya-bahu, implying the golden arm, or branch of a river, or the golden canal or channel. These expressions imply an arm or branch of the Sona, which really forms two branches before it falls into the Ganges....

[Called "golden" because it's a place of shelter for large trading boats carrying gold and wealth during the monsoon.]

The epithet of golden does by no means imply that gold was found in its sands. It was so called, probably, on account of the influx of gold and wealth arising from the extensive trade carried on through it; for it was certainly a place of shelter for all the large trading boats during the stormy weather and the rainy season.

In the extracts from Megasthenes by Pliny and Arrian, the Sonus and Erannoboas appear either as two distinct rivers, or as two arms of the same river. Be this as it may, Arrian says that the Erannoboas was the third river in India, which is not true. But I suppose that Megasthenes meant only the Gangetick provinces: for he says that the Ganges was the first and largest. He mentions next the Commenasis or Sarayu, from the country of Commanh, as a very large river. The third large river is then the Erannoboas or river Sona.

[The "Hiranaya-baha/Hiranya-bahu" is said to be "well known to this day to every school boy," but has "0" presence on Google minus Asiatick Researches.]

Ptolemy, finding himself peculiarly embarrassed with regard to this river, and the metropolis of India situated on its banks, thought proper to suppress it entirely. Others have done the same under similar distressful circumstances. It is however well known to this day, under the denomination of Hiranya-baha, even to every school boy, in the Gangetick provinces, and in them there is no other river of that name.[???!!!]...

[Called "Puna-Puna/Again-and-again" because "mystically" it removes sins "again and again"; called "Magadha/Cicati/Megasthenes Cacuthis" because it flows through the country of "Magadha/Cicata".]

The next river is the Puna-puna [Punpun: Wiki], which signifies again and again, in a mystical sense[???]; for it removes sins again and again. It is a most holy stream, and is called also Magadha, because it flows through the country of Magadha or Cicata. Hence this river might be called also Cicati, and it is the Cacuthis of Megasthenes....

[Called "Chandan" because it flows through the groves of Chandra; called "Goga," which should "rightly" be called "Cauca," because it falls into Ganges at a place called "Cucu"; called in the Jina-vilas "Aranya-baha," because it's "a torrent from the wilderness."]

Let us now proceed to the Sulacshni, or Chandravati, according to the Cshetra-samasa. It is now called the river Chandan, because it flows through the Van or groves of Chandra, in the spoken dialects Chandwan, or Chandan. In the maps it is called Goga, which should be written Cauca, because according to the above tract, it falls into the Ganges, at a place called Cucu, and in a derivative form Caucava, Caucwa, or Cauca. It flows a little to the eastward of Bhagalpur: but the place, originally so called, has been long ago swallowed up by the Ganges, along with the town of Bali-gram. In the Jina-vilas, it is called Aranya-baha[!!!], or the torrent from the wilderness, being really nothing more....

[Called "Rada" because it flows through the country of "Radha."]

The Rada, now the Bansli [Bansloi: Wiki], falls into the Ganges near Jungypur [Jangipur: Wiki]. I believe it should be written Radha, because it flows through the country of that name.

The Dwaraca [Dwarka: Wiki] is next:

[Called "Mayhuracshi/Peacock-eyes".]

Then, the Mayuracshi [Mayhurakshi: Wiki], or with the eyes of a Mayura, or peacock [Peacock Eyes: Wiki]; this is the river More....

[Called "Bacreswari" because it comes from the hot wells of "Bacreswara-mahadeva", now the "Bakreshwar Thermal Power Station".]

The next river is the Bacreswari [Bakreshwar: Wiki], which comes from the hot wells of Bacreswara-mahadeva, or with the crooked Linga....

[Called "Aji/full of resplendence"; Megasthenes' "Asmytis" should be "Amystis, the pronunciation of "Ajmati."]

The Aji, or resplendent river, is the next: its name at full length is Ajavati or Ajamati, full of resplendence. The Ajmati, as it is pronounced, is the Amystis of Megasthenes, instead of Asmytis....

[Called by the Cshetra-samasa "Damodara", a sacred name of Vishnu; Wikipedia says "Damodar" means "rope around the belly," which is another name of "Krishna", because his foster-mother, Yashoda, tied him to a large urn.]

The next river is the Damodara [Damodar: Wiki], one of the sacred names of Vishnu, and according to the Cshetra-samasa, it is the Vedasmriti, or Vedavati of the Puranas. Another name for it is Devanad, especially in the upper parts of its course....

[Called "Suvarna-recha/streak of gold," for the gold found in the riverbed according to Wikipedia; called "Suctimati" in the Puranas because it flows from the "Richsha" Bear mountains, meaning "abounding with shells."]

Then comes the Suvarna-recha [Subarnarekha/Swarnarekha: Wiki], or Hiranya-recha, that is to say the golden streak [Subarnarekha, meaning "streak of gold": Wiki]. It is called also in the Puranas, in the list of rivers, Suctimati, flowing from the Ricsha, or bear mountains. Its name signifies abounding with shells, in Sanscrit Sucti, Sancha, or Cambu....

The fourth river is the Maha-nada or Maha-nadi [Mahanadi/Hirakud Dam: Wiki], that is to say the great river. It is mentioned in the lists of rivers in the Puranas, but otherwise it is seldom noticed....

[Called "Dosaron" by Ptolemy; but Wikipedia says Ptolemy called it "Manada."]

Ptolemy considers the Cocila and Brahmani rivers as one, which he calls Adamas, or diamond river, and to the Maha-nadi he gives the name of Dosaron. He is however mistaken: the Maha-nadi is the diamond river, and his Dosaron consists of the united streams of the Brahmani and the Cocila, and is so called because they come from the Dasaranya, also Dasarna, or the ten forest-cantons. He might indeed have been led into this mistake very easily, for the Brahmani and Cocila come from a diamond country in Chuta-Nagpur, and in Major Rennell’s general map of India, these diamond mines towards the source of these two rivers are mentioned, and seem to extend over a large tract of ground....

Mouth of the Manada: —Ptolemy enumerates four rivers which enter the Gulf between Kannagara and the western mouth of the Ganges, the Manada, the Tyndis, the Dosaron and the Adamas. These would seem to be identical respectively with the four great rivers belonging to this part of the coast which succeed each other in the following order: -- The Mahanadi. the Brahmani, the Vaitarani and the Suvarnarekha, and this is the mode of identification which Lassen has adopted. With regard to the Manada there can be no doubt that it is the Mahanadi, the great river of Orissa at the bifurcation of which Katak the capital is situated. The name is a Sanskrit compound, meaning 'great river.' Yule differs from Lassen with regard to the other identifications, making the Tyndis one of the branches of the Mahanadi, the Dosaron,—the Brahmani, the Adamas,—the Vaitarani and the Kambyson (which is Ptolemy’s western mouth of the Ganges) -- the Suvarnarekha.

The Dosaron is the river of the region inhabited by the Dasarnas, a people mentioned in the Vishnu Purana as belonging to the south-east of Madhya-desa in juxtaposition to the Sabaras, or Suars. The word is supposed to be from dasan ‘ten' and rina 'a fort,' and so to mean 'the ten forts.'

Adamas is a Greek word meaning diamond. The true Adamas, Yule observes, was in all probability the Sank branch of the Brahmani, from which diamonds were got in the days of Mogul splendour.

Sippara:—The name is taken by Yule as representing the Sanskrit Sarparaka. Para in Sanskrit means 'the further shore or opposite bank of a river.'

Minagara: -- The same authority identifies this with Jajhpur. In Arrowsmith's map I find, however, a small place marked, having a name almost identical with the Greek, Mungrapur, situated at some distance from Jajhpur and nearer the sea.

Kosamba is placed by Yule at Balasor, but by Lassen at the mouth of the Subanreckha which, as we have seen, he identities with the Adamas. There was a famous city of the same name, Kansambi, in the north-went of India, on the River Jumna, which became the Pandu capital after Hastinapuru had been swept away by the Ganges, and which was noted as the shrine of the most sacred of all the statues of Buddha. It is mentioned in the Ramayana, the Mahavansa, and the Meghaduta of Kalidasa. It may thus be reasonably concluded that the Kosamba of Ptolemy was a seat of Buddhism established by propagandists of that faith who came from Kansambi.

-- Ancient India: as described by Ptolemy; being a translation of the chapters which describe India and Central and Eastern Asia in the treatise on geography written by Klaudios Ptolemaios, the celebrated astronomer, by J. W. McCrindle, M.A., M.R.A.S., Late Principal of the Government College, Patna, and Fellow of the University of Calcutta, 1885

[Called "Damiadee," but it's real name should be "Dhumyati," from the mist-like smoke arising from its bed; several rivers in India are so-called; "Hiranya-baha" is called "Cujjhati/Cuhi" from "Cuha," a mist arising from its bed, but since the "Hiranya-baha" has nearly disappeared, this fog is no longer seen, as is also the case with the "Dhumyati;" "Damiadee" is now called "Lohree/Rohree" from a town of that name near its confluence with the Indus; there are no search results for any of these names on Google.]

The Damiadee[???] was first noticed by the Sansons in France, but was omitted since by every geographer, I believe, such as the Sieur Robert, the famous D’Anville, &c; but it was revived by Major Rennell, under the name of Dummody. I think its real name was Dhumyati, from a thin mist like smoke, arising from its bed. Several rivers in India are so named: thus the Hiranya-baha, or eastern branch of the Sona, is called Cujjhati, or Cuhi† [Commentary on the Geog. of the M. Bh.] from Cuha, a mist hovering occasionally over its bed. As this branch of the Sona has disappeared, or nearly so, this fog is no longer to be seen. I think, this has been also the fate of the Dhumyati, which is now absorbed by the sands.... The Damiadee is now called by the natives, Lohree or Rohree, from a town of that name, near its confluence with the Indus....

[Wikipedia says "Charmanwati" is a river mentioned in the Mahabharata, believed to be the ancient name of "Chambal" river, meaning "river on whose banks leather is dried"; Mahabharata refers to "Chambal" as "Charmanyavati", originating in the blood of thousands of animals sacrificed by King Rantideva on the banks of Charmanwati.]

The next is the Charmmanwati [Charmanwati: Wiki], or abounding with hides. It is often mentioned in the Puranas, and is called also Charmmabala, and Sivanada, in the spoken dialects Chambal and Seonad. It is sometimes represented as reddened with the bloody hides put to steep in its water.* [In the Megha Data[???] this river is said to have originated in the blood shed by Ranti Deva at the Gomedhas, or offerings of kine.]...

There is a town called Sibnagara[???], or more generally Seonah[???], the town of Siva, after whom this river is denominated....

[Wikipedia says the Rigveda names a river "Sindhu," which is thought to be the "Indus"; there is another river called "Sindh", which is a tributary of the "Yamuna".]

The Sindhu[???] or Sind[???], is occasionally mentioned in the Puranas, as well as the little river Para, commonly called Parvati, which, after winding to the north of Narwar, falls into the Sindhu near Vijayagar. It is famous for its noisy falls, and romantic scenes on its banks, and the numerous flocks of cranes and wild geese to be seen there, particularly at Buraicha west of Narwar....

[Called "Vetrarati/abounding-with-withies".]

The Vetrarati [Betwa/Shuktimati, "In Sanskrit 'Betwa" is Vetravati": Wiki], or abounding with withies [a tough, flexible branch of an osier or other willow, used for tying, binding, or basketry.], is a most sacred river. Vetra or Betra is a withy, and so is Vithr in the old Saxon. In the spoken dialects and in English, the letter R is omitted; in Hindi they say Beit and in English With or withy. In the spoken dialects, it is called Betwa and Betwanti....

The Chambal or the Carmanvati rises from the Aravalli range northwest of Indore and flows north-east through eastern Rajputana into the Yamuna. The Kalisindh flows north from the Vindhya range to join the Chambal on the right a little north of Piparda. The Parvati is a local river of indore which flows north-west to join the Chambal on the right. According to Cunningham it is the Para of the Puranas. The Kunu is a right lower tributary of the Chambal, and the Mej is its first left tributary. The Berach, a tributary of the Chambal, rises from the Aravalli range. The point where the Berach receives the Dhund, becomes known as the Banas (Skt. Varnasa). The Gambhira is a tributary of the Yamuna above the Chambal flowing east from Gangapur. The Vetravati (modern Betwa) rises from the Paripatra mountains. In its course towards the Yamuna it is joined by many tributaries. The Ken (Cainas according to Arrian) is an important tributary of the Yamuna below the Vetravati ....

-- Historical Geography of Ancient India, by Bimala Churn Law, M.A., L.L.B., Ph.D., D.Litt, Membre d'Honneur de la Societe Asiatique of Paris, Hon. Fellow Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Hony. Member Royal Asiatic Society Ceylon; Fellow Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal; Author Tribes in Ancient India; History of Pali Literature; Geography of Early Buddhism; Geographical Essays; The Magadhas in Ancient India, etc., with a preface by Prof. Louis Renou

[Called "Saravati" because "Saravan/Saraban" is "a thicket of reeds" on its banks; called "Su-Vama" in the Mahabharata because it is "most beautiful"; called "Sushoma" in the Bhagavat because it is "most beautiful"; also called "Beautiful Shoma/Soma"; called "Sausami/Su-sami" in the Amara-cosa, which is declared to be the "Isamus" of Strabo, the boundary to Menander's kingdom.]