Part 6 of 6

It is clear that Ziegenbalg used the word ajnana (ignorance) for sin, heathendom, and idolatry. On the other hand, ajnana (knowledge or wisdom) stood for monotheism and the acceptance of Jesus as savior. For Ziegenbalg, ajnana involves the veneration of false devas and the worship of vikrakams (Skt. vigraha, forms or shapes) made of earth, wood, stone, and metal. By contrast, jnana signifies the exclusive worship of Baribarawastu (Skt. paraparavastu, divine substance). The point Aleppa kept making in his apologetic letters was exactly that his native religion was fundamentally a monotheistic jnana, rather than a heathen ajnana,

and it seems that he was highly motivated to help the missionaries find Tamil texts that proved exactly this point....

From the beginning, the antibrahmanical and antihierarchical tendency of Siddha writings was prominent, as in Tirumular's oft-quoted lines, "Caste is one and God is one" (p. 386). But the God referred to here is not exactly the one whom de Nobili and Ziegenbalg worshipped, and this saying does not signify "mankind is one and God is one." Rather, as Kailasapathy explains, Tirumular meant that "insofar as religious worship was concerned, all castes are equal and the only god is Shiva".-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

...

Indians who are not only naturally monotheist but even profess faith in the very same God that the German pastors evoked in their sermons: "a God who created everything, reigns over everything, punishes evil, rewards good deeds, and who must be feared, loved, worshipped, and prayed to"... Because they relied exclusively on reason that "since the Fall is entirely misguided and spoiled," they eventually "let themselves be seduced by Satan in various ways." Nevertheless, from time immemorial, they fundamentally accept and worship an invisible divine being and have texts to prove this:

Such truth gained from the light of nature is not a recent thing with them but a very ancient one; they have books that are said to be more than 2000 years old. These form the basis of their opinions in these matters, and they hold that their religion is the oldest of all; it may have originated not long after the deluge. They not only believe in one God but have by the light of nature come so far as to accept no more than one single divine being as the origin of all things. Even though they worship many gods, they hold that all such gods have sprung from a single divine being and will return therein; so that in all gods only that single divine being is worshipped. Those among them who are a bit learned will defend this very obstinately even though they cannot deliver any proof of it. (pp. 37-38)

-- Bibliotheca Malabarica: Bartholomaus Ziegenbalg's Tamil Library, by Will Sweetman with R. Ilakkuvan

... Relation des erreurs qui se trouvent dans la religion des gentils malabars de la Coste Coromandelle. This work...opens, much like Ziegenbalg’s Genealogia, with a discussion of Hindu conceptions of the divine. Unlike Ziegenbalg, however, the author makes only the most general of references to his textual sources: [x] [Google translate: “in one place of their doctrine…they say that God is a spiritual and immense substance, and a few lines later they assert that the air is God”]

A note on the format of the edition74

The text of this edition reproduces the German text of the Bibliotheca Malabarica published by Germann in 1880. Germann’s edition is not easily accessible and is printed in a blackletter typeface which is difficult to read.

Where Germann’s text differs significantly from that in the other manuscripts, this has been noted. In the translation which follows,

we attempt to stay closer to Ziegenbalg’s German than does Gaur in her translation, and we translate the full text. Ziegenbalg’s transliteration of Tamil words and the titles of the texts is retained in the reprinted German text; the translation provides a transliteration which follows the most widely used conventions. In cases where no manuscript or published edition of the work in question has been identified, and the transliteration is therefore to some degree speculative, this has been indicated by an asterisk preceding the title of the work.

75 The translation is augmented by annotations which attempt identification of the work in question, comment on Ziegenbalg’s characterisation of it, and summarise his use of the work and any further account he gives of the work in his other writings. Where two or more closely related works are listed together, the annotation follows the last work.

76 Where the work has been published, details of editions have been provided following the annotation. In identifying editions of works published many times we have tried to strike a balance between noting significant historical editions, accessibility, and quality of the published edition, but in many cases—particularly major works of Tamil literature—other editions could have been cited. Where translations into European languages exist, works which include full or substantial translations have been cited. Here the choice of works has been much more limited. Where translations into several languages exist, preference has been given to those into English. Where multiple translations into English exist, we have for the most part relied on the judgments of others in choosing to cite a particular translation. No systematic attempt has been made to cite other critical works on each of the texts in Ziegenbalg’s collection except where these have been relied on in the annotations. References to these works are thus confined to the footnotes, rather than following the editions and translations cited in the main text.

77 The marginal references (BM) indicate the numbering provided by Germann in his edition. Where Ziegenbalg’s entry is very short, only a single marginal reference is provided, but because in some cases his entry extends over more than one page, marginal references are typically provided for both the German text and the English translation.

___________________

Notes:1 Kamil V. Zvelebil, Tamil Literature, A History of Indian Literature X. 1 (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1974), 2.

2 Hans-Werner Gensichen, “B. Ziegenbalgs Rezeption der Tamil-Spruchweisheit”, Neue Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft 45, no. 2 (1989): 86.

3 Ziegenbalg to Christian von der Linde, Tranquebar, 5 September 1706, in Arno Lehmann, ed., Alte Briefe aus Indien: Unveröffentlichte Briefe von Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg 1706–1719 (Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 1957), 32–3. Both here and in an earlier letter (Ziegenbalg to friends in Germany, Cape of Good Hope, 30 April 1706, in ibid., 25), Ziegenbalg emphasizes his reluctance.

4 Ziegenbalg to Francke, Berlin, 7 October 1705, in ibid., 21.

5 Ziegenbalg to von der Linde, Tranquebar, 5 September 1706, in ibid., 33.

6 Ziegenbalg to Francke, Tranquebar, 1 October 1706, in ibid., 43. Cf. Ziegenbalg to friends in Germany, Cape of Good Hope, 30 April 1706, in ibid., 25.

7 Baldaeus’s work, first published in Dutch in 1672, was translated into German the same year. The third section, on the “Idolatry of the East-Indian Heathens” (edited by Albertus Johannes de Jong, Afgoderye der Oost-Indische Heydenen door Philippus Baldaeus opnieuw utgegeven en van inleiding en aantekeningen voorzien (’s-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1917)), is taken almost entirely from two earlier works, one by a Portuguese Jesuit, Jacobo Fenicio (Jarl Charpentier, The Livro da seita dos Indios orientais (Brit. mus. MS. Sloane 1820) of Father Jacobo Fenicio, S.J. (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells, 1933), lxxxiii–lxxxiv), and the other by a Dutch artist, Philips Angel (Siegfried Kratzsch, “Die Darstellung der zehn Avatāras Viṣṇus bei Philippus Baldaeus und ihre Quellen”, in Kulturhistorische Probleme Südasiens und Zentralasiens, ed. Burchard Brentjes and Hans-Joachim Peuke (Halle: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1984), 105–19). Ziegenbalg’s use of Baldaeus’s work is discussed further below (31, 44).

8 Ziegenbalg, Cape of Good Hope, 30 April 1706, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 25.

9 Willem Caland, ed., B. Ziegenbalg’s Kleinere Schriften, Verhandelingen der Kon. Akad. der Wetensch., Afd. Letterkunde. Nieuwe Reeks, XXIX/2 (Amsterdam: Uitgave van Koninklijke Akademie, 1930), 11.

10 Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 16 September 1706, in Joachim Lange, ed., Merckwürdige Nachricht aus Ost-Jndien Welche Zwey Evangelisch-Lutherische Prediger Nahmentlich Herr Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg… Und Herr Heinrich Plütscho… den 30. April 1706. aus Africa… Und bald darauf aus Trangebar von der Küste Coromandel, an einige Predige und gute Freunde in Berlin überschrieben.… Die andere Auflage (Leipzig and Franckfurt am Mayn: Joh. Christoph Papen, 1708), 14.

11 Ziegenbalg to Francke, Tranquebar, 1 October 1706, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 44.

12

Ziegenbalg’s servant Mutaliyāppaṉ, who knew Portuguese and Tamil and was learning German from Ziegenbalg, translated from Ziegenbalg’s rudimentary Portuguese in these early exchanges (Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 16 September 1706, in Lange, Merckwürdige Nachricht, 14). By 12 October 1706, Ziegenbalg and his colleague had the services of a former translator to the Danish East-India Company named Aḻakappaṉ who, in addition to Portuguese and Tamil, knew Danish, German, and Dutch (Kurt Liebau, ed., Die malabarische Korrespondenz: tamilische Briefe an deutsche Missionare; eine Auswahl, Fremde Kulturen in alten Berichten (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1998), 20).

13 Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 2 September 1706, in Christian Gustav Bergen, ed., Herrn Bartholomäi Ziegenbalgs und Herrn Heinrich Plütscho… Brieffe, Von ihrem Beruffund Reise nach Tranqvebar, wie auch Bißhero geführten Lehre und Leben unter den Heyden… An einige Prediger und gute Freunde… geschickt, Jetzund vermehret, mit etlichen Erinnerungen, und einem Anhange unschädlicher Gedancken von neuem herausgegeben von Christian Gustav Bergen. Die dritte Aufflage (Pirna: Georg Balthasar Ludewig, 1708), 21.

[Google translate: Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 2 September 1706, in Christian Gustav Bergen, ed., Mr. Bartholomäi Ziegenbalgs and Mr. Heinrich Plütscho... Letters, From their professional journey to Tranquebar, as well as Bishero, their teaching and life among the Heathen... To some preachers and good friends ... skillfully, now and increased, with a number of memoirs, and an appendix of innocuous thoughts re-edited by Christian Gustav Bergen. The third edition (Pirna: Georg Balthasar Ludewig, 1708), 21.]

14 Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 25 September 1706, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 40.

15 Caland, Ziegenbalg’s Kleinere Schriften, 11.

16 Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 2 September 1706, in Bergen, Ziegenbalgs… Brieffe, 19. Cf. Ziegenbalg’s comment in a letter written a fortnight later: “Ich muß bezeigen, daß mir mein 70. Jahriger Schulmeister offt, solche Philosophische Fragen fürleget, daraus ich abnehmen kan, daß in ihren Büchern schon solche Sachen würden angetroffen werden, daran die Gelehrten in Europa ihrer Curiosität ein Genügen thun könten. Ich suche mit Fleiß dahinter zu kommen, und lass sie mit grossen Unkosten abschreiben.” (Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 16 September 1706, in Lange, Merckwürdige Nachricht, 16).

[Google translate: Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 2 September 1706, in Bergen, Ziegenbalgs… Brieffe, 19. Cf. Ziegenbalg's comment in a letter written a fortnight later: “I have to show that

my 70-year-old schoolmaster often asks me such philosophical questions, from which I can conclude that such things would already be found in your books, as did the scholars in Europe could satisfy their curiosity. I am diligently trying to find out, and having them copied at great expense.” (Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 16 September 1706, in Lange, Strange Message, 16).]

17 Versions of the letter were published in both German and English. The following summary is taken from the full transcription in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 77.

18

This incident arose from Ziegenbalg’s intervention on behalf of the widow of a Tamil barber, over a debt between her late husband and a Catholic who was employed by the Company as a translator. Hassius regarded Ziegenbalg’s repeated intervention in the case, including his advice that she kneel before him in the Danish church, as inappropriate and sent for Ziegenbalg to appear before him. When Ziegenbalg demurred, requesting a written summons, he was arrested and, because he refused to answer questions, imprisoned. For more detailed accounts of the episode, see Anders Nørgaard, Mission und Obrigkeit: Die Dänisch-hallische Mission in Tranquebar, 1706–1845 (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus/Gerd Mohn, 1988), 41–48 and Ulla Sandgren, The Tamil New Testament and Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg: A Short Study of Some Tamil Translations of the New Testament. The Imprisonment of Ziegenbalg 19.11.1708–26.3.1709 (Uppsala: Swedish Institute of Missionary Research, 1991), 91–95.

19 See Daniel Jeyaraj, Erschliessung der Tamil-Palmblatt-Manuskripte (Halle: Archiv der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, 2001).

20

The first Tamil work to be printed, in 1713, was a tract on akkiyāṉam, “heathenism.” Cf. Will Sweetman, “Heathenism, Idolatry and Rational Monotheism among the Hindus: Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg’s Akkiyāṉam (1713) and Other Works Addressed to Tamil Hindus”, in Halle and the Beginning of Protestant Christianity in India, ed. Andreas Gross, Y. Vincent Kumaradoss and Heike Liebau (Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, 2006), 1249–75.

21 hb 6: 283. Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, Ziegenbalg’s Malabarisches Heidenthum, ed. Willem Caland, Verhandelingen der Kon. Akad. der Wetensch., Afd. Letterkunde. Nieuwe Reeks, XXV/3 (1711; Amsterdam: Uitgave van Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen te Amsterdam, 1926).

22 Ācārakōvai (bm 44) is often quoted in this regard, see also the works listed below, 129.

23 See below, 38–40.

24 On a number of occasions, Ziegenbalg cites the titles of sections of larger works. Jeyaraj’s higher estimate of eighty-seven Tamil works mentioned in the Genealogia results from his taking each of these as a separate work. Thus he lists separately Tiruvācakam and “Vāḻāppattu,” the twenty-eighth poem of Tiruvācakam. See Daniel Jeyaraj, Genealogy of the South Indian Deities: An English Translation of Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg’s Original German Manuscript with a Textual Analysis and Glossary (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2005), 202, 330.

25 Ziegenbalg to Lange, Tranquebar, 22 December 1710 in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 173.

26 hb 6: 315. Ziegenbalg spent six months (July 1711 to January 1712) in and around Madras.

27 Ziegenbalg and Gründler to Anton Wilhelm Böhme, Tranquebar, 16 September 1712, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 236. Pace Brijraj Singh, this was never printed, although it was sent to Europe (Brijraj Singh, The First Protestant Missionary to India: Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg (1683–1719) (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), 168).

28 Ziegenbalg, Gründler and Jordan to Francke, Tranquebar, 17 November 1712 in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 276.

29 Ziegenbalg, Gründler and Jordan to Böhme, Tranquebar, 5 January 1713 in ibid., 283–84.

30

A much later mission report stated that the letters were, “for the most part,” written by Ziegenbalg’s early translator, Aḻakappaṉ (hb 25: 149). This, however, is in the context of explaining why the missionaries at the time (Nikolaus Dal, Martin Bosse, Christian Friedrich Pressier, and Christoph Theodosius Walther) had been unable to engage any Tamils in correspondence and the source of their knowledge is unclear, as none had been in India during Ziegenbalg’s lifetime and Dal, the most senior of the four, had arrived only six months before the death of Gründler. On the evidence of the letters themselves, including the letters quoted in his Genealogia, and of Ziegenbalg’s broader correspondence, it is not implausible to think that a number of other authors were involved.31 Ziegenbalg to Michaelis, Bergen, 5 June 1715; Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 22 September 1707, in ibid., 421, 59. For identification of this work see

Will Sweetman, “Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, the Tranquebar Mission, and ‘the Roman Horror’”, in Halle and the Beginning of Protestant Christianity in India, ed. Andreas Gross, Y. Vincent Kumaradoss and Heike Liebau (Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, 2006), 802).

32 A facsimile reprint with brief introduction by Burchard Brentjes and Karl Gallus appeared in 1985: Grammatica Damulica von Bartolomaeus Ziegenbalg, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Wissenschaftl. Beiträge, 44 = I 32 (1716; Halle: Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1985).

33 Ziegenbalg and Gründler to the Mission Board in Copenhagen, Tranquebar, 20 November 1717, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 421, 59.

This scholar was Kaṇapati Vāttiyār, who took the name Friedrich Christian at his baptism. He had earlier been an important source of books for Ziegenbalg’s collection (see below, 32f.). There is no trace of his book, although an earlier manuscript by him survives (AFSt/M tam 87).34 Bibliotheca Malabarica, bestehende in unterschiedlichen malabarischen Büchern, so da handeln I. von der reinen Evangelischen Religion, II. von der unreinen Papistischen Religion, III. von der heynischen Religion der Malabaren, IV. von der Mahometanischen Religion der Mohren, gesammelt und zum Theil selbsten gescrieben von Bartholomeo Ziegenbalg von Seiner Königl. Majestät zu Dennemarck und Norwegen etc. verordneten Missionario unter den malabarischen Heyden auf der Küste Coromandel zu Tranquebar.

[Google translate:

Bibliotheca Malabarica, existing in different Malabar books, I. deal with the pure evangelical religion, II. with the impure papist religion, III. from the Heynian religion of the Malabars, IV. from the Mahometanic religion of the Moors, collected and partly written by Bartholomeo Ziegenbalg from his Königl. Majesty at Dennemarck and Norway, etc., decreed missionary among the Malabar heathen on the Coromandel coast at Tranquebar.]

35 The letter which accompanied the text of the Bibliotheca Malabarica, together with descriptions—taken from the first section of the Bibliotheca Malabarica—of Ziegenbalg’s sermons, and of the two dictionaries he compiled, was printed in Halle in 1710 in a work later incorporated in the Hallesche Berichte. The full text of the remainder was published by Wilhelm Germann in 1880 (“Ziegenbalgs Bibliotheca Malabarica”, Missionsnachrichten der Ostindischen Missionsanstalt zu Halle 22 (1880): 1–20, 61–94).

36 Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 22 September 1707, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 59.

37 As Ziegenbalg had reported just three days earlier, that “preaching and catechising in public” in Tamil was still “a little too hard” for him (Ziegenbalg to Frederik IV, Tranquebar, 19 September 1707, in ibid., 55) we can assume that he means within eight months of acquiring the Catholic works in Tamil, not within eight months of his arrival in Tranquebar.

38 Germann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica”, 9–10.

39 Stephen Neill, A History of Christianity in India, vol. I: The Beginnings to AD 1707 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 304.

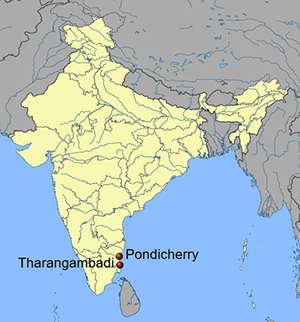

40 A brief account in the Lettres édifiantes et curieuses (Guy Tachard to Père de la Chaise, Pondicherry, 16 February 1702 in Charles le Gobien, ed., Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, écrit des missions étrangères par quelques missionaires de la Compagnie de Jésus, 34 vols., Paris (Chez Nicolas Le Clerc, 1702–76), 3: 212–16) reports that

many Christians were driven out of Tanjore, and two Jesuits were imprisoned. Although one of many, at the time of Shahji’s death in 1712 this event was recalled as particularly severe—and as resulting in the exclusion of missionaries from Tanjore until 1712 (Louis de Bourzes, Litterae Annuae Missionis Madurensis, 1712).

41 We are grateful to Torsten Tschacher for his comments on these works.

42 Ronit Ricci, Islam Translated: Literature, Conversion, and the Arabic Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 98–128.

43 See below (23–27) for details of two partial copies of this section (the Sloane and Mackenzie Collection manuscripts) and of Walther’s edition of Ziegenbalg’s catalogue.

44 Kathleen Iva Koppedrayer, “The Sacred Presence of the Guru: The Velala lineages of Tiruvavatuturai, Dharmapuram, and Tiruppanantal” (PhD diss., McMaster University, 1990), 163.

45 “Sámawédum, Urúkkuwédum, Edirwárnawédum und Adirwédum” (hb 7: 374).

46 The letters published in the seventh and eleventh instalments of the Hallesche Berichte as the “Malabarische Correspondenz” are often assumed to have been chosen, translated, and annotated by Ziegenbalg. In his edition of some of these letters, Kurt Liebau argues that in fact the translation and annotations are substantially the work of Gründler (Liebau, Malabarische Korrespondenz, 26–27). However, as Liebau acknowledges, Gründler used Ziegenbalg’s works on Hinduism for the annotations and they repeat many details which are to be found in the Malabarisches Heidenthum and Genealogia which were written just prior to and just following, respectively, the annotation of the first batch of letters. We can therefore assume that Ziegenbalg would have identified himself with the position of the annotations, although he might not have been responsible for the way in which that position was expressed. We therefore do not attach importance to the question of which of the missionaries was responsible for the annotations and refer to the author of the annotations only as “the missionary,” intending thereby to indicate their joint agency and to avoid the problem of distinguishing their precise contribution.

47 On the concept of the “branch story” (kiḷaikkatai) in Tamil literature see Paula Richman, Women, Branch Stories, and Religious Rhetoric in a Tamil Buddhist Text (Syracuse: Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, Syracuse University, 1988), 37–39.

48 mh 24–26, 29–33, 50, 52–56, 58–62, 68–69, 74, 78–79, 102, 144–48, 151–52, 161–63, 169–71, 204–5, 221–22, 249–51. The text of Ziegenbalg’s manuscript seems to have differed slightly from that found in most published editions of Parañcōti’s work. Although the order of episodes is mostly the same—and certainly follows the later, chronological, ordering of the episodes—from chapters 13 to 28 Ziegenbalg consistently numbers the episodes one lower, and from 30 to 38 one higher, than Parañcōti. The early episodes he cites (2–4) are also numbered higher, but from 48 to 64 his numbering is the same as that in published editions of the purāna.

49 See the section on Śaiva purāṇams in the Genealogia below (131).

50 See the discussion in Richard S. Weiss, Recipes for Immortality: Medicine, Religion, and Community in South India (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 47–50.

51 Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HIL), 193; V. Murugan, A Dictionary of Tamil Literary and Critical Terms (Chennai: Institute of Asian Studies, 1999), s.v. ciṟṟilakkiyam.

52 Kamil V. Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1992), 271.

53 Paula Richman, Extraordinary Child: Poems from a South Indian Devotional Genre (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997), 238.

54 Crispin Branfoot, Gods on the Move: Architecture and Ritual in the South Indian Temple (London: British Academy/Society for South Asian Studies, 2007), 128.

55

Maṭal refers to the jagged stem of a palmyra leaf on which a man vows to die by riding like a horse if his beloved will not accept him.56 “A poem in which the last syllable or foot of the last line of a stanza… is identical with the first syllable or foot of the following stanza” (Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HIL), 195).

57 Short, sophisticated poems in eight stanzas.

58 Poem of one hundred stanzas.

59 Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HIL), 216.

60 See also the reference above to folk works in Ziegenbalg’s collection which represent episodes from the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa.

61 Indira Viswanathan Peterson, “The Evolution of the Kuṟavañci Dance Drama in Tamil Nadu: Negotiating the ‘Folk’ and the ‘Classical’ in the Bhārata Nātyam Canon”, South Asia Research 18, no. 1 (1998): 48–49.

62 Ammāṉai is the name given to “a ballad-like narrative genre” of poems which “had in each verse ammāṉāy as refrain” (Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HIL), 195).

63 For details, see the entries for the works below.

64 Hephzibah Israel, “Protestant Translations of the Bible in Indian Languages”, Religion Compass 4, no. 2 (2010): 88.

65 Shu Hikosaka and G. John Samuel, A Descriptive Catalogue of Palm-Leaf Manuscripts in Tamil, 5 vols. (Madras: Institute of Asian Studies, 1990–97), 1: xvi.

66 Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HIL), 2.

67 The catalogues of manuscripts which the Jesuits sent to Paris in the 1720s and 1730s offer ample evidence for their knowledge of, and access to, Indian literature. See, for example, the catalogue of manuscripts sent in 1729–35 (Bibliothèque nationale NAF 5442), printed in Henri Auguste Omont, Missions archéologiques françaises en Orient aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Imprimerie nationale: Paris, 1902), 1179–92.

68 See, for example, the Relation des erreurs qui se trouvent dans la religion des gentils malabars de la Coste Coromandelle. This work—which has been variously attributed to Roberto de Nobili, João de Brito, and Jean Venant Bouchet—opens, much like Ziegenbalg’s Genealogia, with a discussion of Hindu conceptions of the divine. Unlike Ziegenbalg, however, the author makes only the most general of references to his textual sources: “dans un endroit de leur doctrine… ils disent que Dieu est une substance spirituelle et immense, et quelques lignes apres ils assurent que l’air est Dieu” [Google translate:

“in one place of their doctrine…they say that God is a spiritual and immense substance, and a few lines later they assert that the air is God”] (Willem Caland, ed., Twee oude Fransche verhandelingen over het hindoeïsme, Verhandelingen der Kon. Akad. der Wetensch., Afd. Letterkunde. Nieuwe Reeks, XXIII/3 (Amsterdam: Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen, 1923), 3).

69 For example, Apirāmi antāti (bm 25) or Ulakanīti (bm 100).

70 Ziegenbalg to Michael Weitzmann, Tranquebar, 7 October 1709, in Alte Briefe, 120.

71 Civārccaṉā pōtam, *Apiṣēkappalaṉ, Snāṉaviti, Tirumantiram, Cāmuttirikā laṭcaṇam, Kanta purāṇam, Viruttācala purāṇam, and Piramōttara kāṇṭam.

72 Christian Friedrich Pressier to Francke, Tranquebar, 10 January 1726:

H. Walther hat schon geschrieben, daß die von Sel. Pr. Ziegenbalg mit großer Mühe verfertigten Göttergenealogie uns hier fehlt. Ew. Hoch-Ehw. wollen doch Sorge tragen, daß uns dieselbe übersandt werde. Es muß nach dem Tode deßelben nicht recht nach den Büchern gesehen worden seyn. Er hatte viele kostbare Malabarische Bücher angeschafft, selbige sind meistens distrahiert, und haben diejenigen die was davon erhalten können, es zu sich genommen und verkaufft. Ein Schulmeister, der damals noch Schulknabe gewesen erzehlt; Als es mahl etwas kalt gewesen, so hätte da ein Kasten mit dergleichen Olesbüchern gestanden, den hätten sie in Gegenwart des Schulmeisters geöffnet, von den Büchern ein Feuer angezündet, und sich dabey gewärmet.… Solte der Sel. Zieg. vorher gewußt haben, daß sein Ende so nahe, so würde er ohne Zweifel den Successoribus zum besten noch alle dergleichen dingen in bessere disposition gebracht und davon Nachricht hinterlaßen haben.

Archiv der Franckeschen Stiftungen/Missionsarchiv (AFSt/M) 1 B 2: 41.

73 Christoph Theodosius Walther, Bibliotheca Tamulica, consistens in recensione librorum nostrorum, mscr-torum ad cognoscendam et linguam & res Tamulicas inseruientium, 1731, Royal Library, Copenhagen, Ny. Kgl. Saml. 589C, 3.

74 Zvelebil, Companion Studies, 43–91. On this trope see also Herman Tieken, “Blaming the Brahmins: Texts Lost and Found in Tamil Literary History”, Studies in History 26, no. 2 (2010): 227–43.

75 Norman Cutler, Songs of Experience: the Poetics of Tamil Devotion (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 55.

76 In 1857, William Taylor wrote “I was told some years ago that the ascetics (or Pandárams) of the Saiva class seek after copies of this poem with avidity, and uniformly destroy every copy they find. It is by consequence, rather scarce, and chiefly preserved by native Christians” (William Cooke Taylor, A Catalogue Raisonnée [sic] of Oriental Manuscripts in the Library of the (late) College, Fort Saint George, now in charge of the Board of Examiners, 3 vols. (Madras: Printed by H. Smith, 1857–62), 3: 26); cf. Zvelebil, Companion Studies, 47.

77 Zvelebil, Companion Studies, 44–46.

78 Rebecca Knuth, Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist Violence and Cultural Destruction (Westport: Praeger, 2006), 80–87.

Perhaps the closest analogy however is the fate of the manuscripts collected by Francis Whyte Ellis. Like Ziegenbalg, he died prematurely and, according to Walter Elliot, a cook is said to have used his manuscripts to light the kitchen fire (Thomas R. Trautmann, Languages and Nations: The Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 77, 107).

Evelyn Masilamani-Meyer notes that “professional singers use palm leaf manuscripts as fire wood to cook their meagre portions of rice” (“The Changing Face of Kāttavarāyan”, in Criminal Gods and Demon Devotees: Essays on the Guardians of Popular Hinduism, ed. Alf Hiltebeitel (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 98).

79

At a conference in 2006 marking the tercentenary of Ziegenbalg’s arrival in India, one scholar argued that the manuscripts, like the Elgin marbles or the Rosetta stone, represented a stolen patrimony that should be returned to Tamil Nadu.80 Jeyaraj, Tamil-Palmblatt-Manuskripte.

81 This catalogue, exists in a number of forms: in German under the title “Katalog der in Madras, Tranquebar, Kopenhagen und Halle vorhandenen Bücher in telugischer und tamilischer Sprache,” dated 17 December 1744 (AFSt/M 2 B 7: 13); in Latin under the title “Catalogus. Librorum et Tractatuum, quos partim in Tamulicam, Telugicam, Hindostanicam, Lusitanicam etc. linguas transtulit, partim ipse conscripsit. 1720-1748,” dated 17 December 1744 (AFSt/M 2 B 7: 14a); and in Tamil characters under the Tamil title “Tamiḻpottakaṅkaḷuṭaiya aṭṭavaṇai” and with a note in German “Verlangtes Verzeichniß unserer Malabarischen Bücher,” undated (AFSt/M 2 B 7: 14b). See also the earlier catalogue by Walther, discussed below (25).

82 Ziegenbalg to [J. J. Breithaupt, P. Antonius, A. H. Francke], Tranquebar, 15 October 1709, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 120.

83 Lütkens died in 1712, but although it is possible Rostgaard acquired the whole catalogue after his death, the fact that the other sections are missing, and the “thin ornate hand” in which it is written, suggests the Sloane manuscript is more likely to have been a copy made in Europe (Albertine Gaur, “Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg’s Verzeichnis der Malabarischen Bücher”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1967): 63).

84 Gaur, “Ziegenbalg’s Verzeichnis der Malabarischen Bücher”.

85 See the closing comments in Gaur’s earlier article describing the Sloane manuscript, which suggest she thought the Bibliotheca Malabarica to have been something other than the “Verzeichnis der Malabarischen Bücher” (Albertine Gaur, “A Catalogue of B. Ziegenbalg’s Tamil Library”, The British Museum Quarterly 30, nos. 3/4 (1966): 104).

86 Ibid., 88–95.

87 Ibid., 67.

88 Several of Gaur’s comments are helpful; others reveal a limited knowledge of Tamil literature, notably her identification of the sixteenth-century Ariccantira purāṇam as “a poem from the Saṅgham period” (Gaur, “Ziegenbalg’s Verzeichnis der Malabarischen Bücher”, 72).

89 Where the differences are significant, they have been noted in the translation below.

90 Arno Lehmann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica: eine wieder entdeckte Handschrift”, Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Gesellschafts- und Sprachwissenschaftliche Reihe 8 (1959): 905.

91 Christian Benedict Michaelis to Ziegenbalg, Gründler and Johannes Berlin, Halle, 1 December 1717 (AFSt/M: 1 C 10: 43).

92 “Recherches Historiques sur l’Etat ancien & moderne de la Religion Chrêtienne dans les Indes”, Tome premier, in Dissertations historiques sur divers sujets (Rotterdam: Chez Reinier Leers, 1707). Cf. Sylvia Murr, “Indianisme et militantisme protestant. Veyssière de La Croze et son Histoire du Christianisme des Indes”, Dix-huitième siècle 18 (1896): 303–23.

93 Mathurin Veyssière de La Croze, Histoire du christianisme des Indes (La Haye: les frères Vaillant et N. Prévost, 1724), 445.

94 Tolkāppiyam (bm 1), Tivākaram (bm 4), Kāraṇai viḻupparaiyaṉ vaḷamaṭal (bm 27), Civavākkiyam (bm 51–3); ibid., 494–96.

95 The story of the devadāsī Poṉṉaṇiyāḷ, ibid., 486–87.

96 Ibid., 470–73.

97 Ibid., 467–68, 473–75.

98 Friedrich Wiegand, “Mathurin Veyssière La Croze als Verfasser der ersten deutschen Missionsgeschichte”, Beiträge zur Förderung Christlicher Theologie 6, no. 3 (1902): 97; Georg Christian Bohnstedt, Herrn M. V. La Croze, Abbildung Des Indianischen Christen-Staats (Halle im Magdeburgischen: Spörl, Grunert, 1727).

99 Urs App argues that prior to the Voltaire’s discovery of the Ezour-Vedam, and the works of the English deists, J. Z. Holwell and Alexander Dow, it was the extracts from Ziegenbalg in La Croze which provided Voltaire’s primary evidence of an ancient Indian monotheism which served his attack on established Christianity (The Birth of Orientalism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010)).

100 The exception is a translation into Telugu by Schultze of a hundred rules on conduct.

101 Walther, Bibliotheca Tamulica, 68.

102 Ibid., 69.

103 Walther, Bibliotheca Tamulica, 3.

104 British Library, Asia, Pacific and Africa Collections, Mss Eur Mack Gen 21 ff.147–60.

105 These details of Cockburn’s life are taken from the account in Charles Lawson, Memories of Madras (London: Swan, 1905), 179–90.

106 NHB 42: 554. John translated Koṉṟai vēntaṉ (AFSt/M 1 C 29b: 106) and Ulakanīti (AFSt/M 2 B 7: 7), as well as Ātticūṭi and Mūturai (AFSt/M 2 B 7: 5–6) into German. His English translations of Koṉṟai vēntaṉ, Ātticūṭi and another work of Auvaiyār, now lost, entitled Kalviyoḻukkam were published in the Asiatick Researches.

107 Hanco Jürgens, “Forschungen zu Sprachen und Religion”, in Geliebtes Europa / Ostindische Welt: 300 Jahre interkultureller Dialog im Spiegel der Dänisch-Hallesche Mission, ed. Heike Liebau (Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen, 2006), 131.

108 Taylor, Catalogue Raisonnée 3: 298.

109 On the scholarly work of John and Rottler see Andreas Nehring, “Natur und Gnade: Zu Theologie und Kulturkritik in den Neuen Halleschen Berichten”, in Missionsberichte aus Indien in 18. Jahrhundert, ed. Michael Bergunder (Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, 1999), 220–245. Nehring rebuts the charge, levelled by several nineteenth-century mission historians that the “enlightened” temper of John and Rottler contributed to the decline of the mission, arguing that they ought instead to be seen as responding to intellectual developments by seeking a new model for mission among Tamils (242–44).

110 Abraham Roger, De Open-Deure tot het Verborgen Heydendom Ofte Waerachtigh vertoogh van het Leven ende Zeden; mitsgaders de Religie, ende Godsdienst der Bramines, op de Cust Chormandel, ende de Landen daar ontrent, ed. Willem Caland, Werken Uitgegeven door De Linschoten-Vereeniging (1651;’s-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1915), 20.

111 Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, A Code of Gentoo Laws, or Ordinations of the Pundits: From a Persian Translation Made from the Original, Written in the Shanscrit Language (London: n.p., 1776), xxxvi.

112 Nehru’s comments are cited by Cannon (Garland Cannon, The Life and Mind of Oriental Jones: Sir William Jones, the Father of Modern Linguistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 229), who notes that “no evidence for this account has been found” and suggests the reasons had more to do with the time of year that Jones sought a teacher, than any reluctance on the part of the Brahmins.

113 Jean-Marie Lafont, “The Quest for Indian Manuscripts by the French in the Eighteenth Century”, in Indika: Essays in Indo-French Relations, 1630–1976 (New Delhi: Manohar, 2000), 90–118.

114 Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 25 September 1706, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 40. Cf. Ziegenbalg to Michael Weitzmann, Tranquebar, 7 October 1709, in ibid., 120.

115 P. Dahmen, “Lettres de Père Calmette”, Revue d’Histoire des Missions (1934): 109–125.

116 “Wenn sie nicht eine so große Liebe zu mir hätten und von mir eine aufrichtige Gegenliebe verspürten, so würden mir sie diese nicht zukommen lassen, wenn ich ihnen gleich für ein jedes Blatt einen Dukaten geben wollte.” Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 25 September 1706, in ibid., 40.

117 Sascha Ebeling, “The College of Fort St George and the Transformation of Tamil Philology during the Nineteenth Century”, in The Madras School of Orientalism: Producing Knowledge in Colonial South India, ed. Thomas R. Trautmann (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009), 238.

118 Germann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica”, 63.

119 Of the letters printed in Lange and Bergen only one is extant in manuscript.

120 The first edition, which appeared already in 1706, contained only one letter, written from the Cape of Good Hope.

121 The second edition edited by Lange appeared in 1708. A further edition by Lange in 1709 was described as a third edition on the title page although Bergen’s edition, also described as the third on the title page, had already appeared in 1708.

122 “Ich war vor einigen Tagen bey einem alten Schul-Lehrer, und hat, daß er mir die drey letzten für gute Bezahlung in ihrer Sprache abschreiben möchte: Aber er konte sich dazu nicht resolviren, indem es wieder ihr Gesätze wäre, einem Christen dergleichen zukommen zu lassen.” (Lange, Merckwürdige Nachricht, 11); cf. “Dergleichen ungereimte Erzehlungen haben die Malabaren in ihren Versen treflich annehmlich zu lesen gemacht, wollen sie aber keinen Christen zukommen lassen, wenn man ihnen gleich viel Geld anbiethet” (ibid., 12).

123 “Die drey letzten lasse ich mir anitzo mit grossen Unkosten in Malabarischer Sprache abschreiben, damit ich von deren Inhalt eine rechte Gewißheit bekommen möge. Wiewohl sie solches noch keinem Christen gethan haben, und würden es auch mir nicht thun, wenn ich mich nicht, als die Apostel, in die durch Freundlichkeit wohl zu schicken wüste, und täglich mit ihnen familiarissime umgienge” (Bergen, Ziegenbalgs… Brieffe, 19). Cf. the comments in Ziegenbalg, Tranquebar, 25 September 1706, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 40, cited above, n. 116.

124 The loss of one of the four Vedas, due to Śiva having cut off one of Brahmā’s four heads, is found in Baldaeus, Wahrhaftige ausführliche Beschreibung, 556.

125 “Das erste handle von der Göttlichkeit und den primis principiis omnium rerum, welches aber mit dem einen Haupte, als er einmahls mit Ispara um die Ober-Stelle gezancket, wäre verloren wordern. Das andre Buch handle von den Gewaltigen, welchen die Herrschaft und Metamorphosi omnium rerum zugeschrieben wird. Das dritte soll lauter gute Moralia in sich begreiffen. Das vierdte handle von den schuldigen Pflichten ihres Götzen= Dienstes” (Bergen, Ziegenbalgs… Brieffe, 19).

126 The idea of a “Tamil Veda,” that is, a work or works in some sense equivalent to the Sanskrit Veda but not a direct translation from it, is widespread and found among both Śaivas (Indira Viswanathan Peterson, Poems to Śiva: The Hymns of the Tamil Saints (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 57) and Vaiṣṇavas (John Braisted Carman and Vasudha Narayanan, The Tamil Veda: Piḷḷāṉ’s Interpretation of the Tiruvāymoḻi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 4). Cf. on the development of this idea Cutler, Songs of Experience, 7–10.

127 For a nineteenth-century account of the tiṇṇai or pyal schools see Charles E. Gover, “Pyal Schools in Madras”, The Indian Antiquary 2, no. 14 (1873): 52–56. See also D. Senthil Babu, “Memory and Mathematics in the Tamil Tiṇṇai Schools of South India in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries”, International Journal for the History of Mathematics Education 2, no. 1 (2007): 15–37, Bhavani Raman, “Disciplining the Senses, Schooling the Mind: Inhabiting Virtue in the Tamil Tiṇṇai School”, in Ethical life in South Asia, ed. Anand Pandian and Daud Ali (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 43–60, Sascha Ebeling, Colonizing the Realm of Words: The Transformation of Tamil Literature in Nineteenth-Century South India (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010), 37–39.

128 John Murdoch, Classified Catalogue of Tamil Printed Books with Introductory Notices (Madras: The Christian Vernacular Education Society, 1865), 215–17.

129 Ātticūṭi, Ulakanīti, Koṉṟai vēntaṉ and Mūturai are among those mentioned explicitly by Murdoch. To these we can probably add Nalvaḻi and Nīti veṇpā, which are listed together with Āṭṭicūṭi, Ulakanīti, Koṉṟai vēntaṉ and Mūturai in the Bibliotheca Malabarica (BM 100–105).

130 Murdoch mentions two catakam texts, the Aṟappaḷḷīcura catakam of Ampalacāṇa Kavirāyar and the Nārāyaṇa catakam of Maṇavāḷa. The former may be later than Ziegenbalg (cf. Kamil V. Zvelebil, Lexicon of Tamil Literature, Handbuch der Orientalistik. Abteilung 2: Indien, 9 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995), 34); the latter is in his collection.

131 Murdoch does not name any particular works, but among those in Ziegenbalg’s collection, Tivākaram and Cūṭāmaṇi nikaṇṭu, would fit the description. Gover mentions “the Nighantu” among the works forming “the grammatical portion of study” (Gover, “Pyal Schools in Madras”, 54).

132 Gover mentions explicitly the Kiruṣṇaṉ tūtu carukkam (an episode from the Uṭṭiyōka paruvam of Villiputtūr āḻvār’s Pāratam) and Kampaṉ’s Irāmāvatāram. Ziegenbalg had the former, and three chapters of the Yutta kāṇṭam of the latter.

133 Ebeling (Colonizing the Realm of Words, 38) notes that Gover’s “Kada Chintamani” (Katacintāmaṇi) could refer to any one of a number of such collections assembled in the nineteenth century. These anthologies postdate Ziegenbalg but he had perhaps a dozen works of the sort they contained, including the Pañcatantira katai (BM 30) which he notes is “much used in schools.”

134 Ziegenbalg to Lütkens, Tranquebar, 22 August 1708, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 79.

135 Germann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica”, 71.

136 Ziegenbalg to Lütkens, Tranquebar, 22 August 1708, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 80.

137 Germann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica”, 84. The sentence reads in full:

“Dieses kleine Büchlein hat mein alter Schulmeister gemacht, den ich anfänglich in Erlernung der malabarischen Sprache gebrauchte, dessen Sohn ein guter Poet ist, und mir sehr viele Bücher verschaffet hat, und oftmals mit mir von erbaulichen Sachen zu disputiren pfleget.” See also Ziegenbalg [to Anton Wilhelm Böhme], Tranquebar, 19 October 1709, in Propagation of the Gospel in the East: Being a Further Account of the Progress made by Some Missionaries to Tranquebar… together with Some Observations relating to the Malabarian Philosophy and Divinity: and concerning their Bramans, Pantares, and Poets, Part II., 2nd ed., trans. [Anton Wilhelm Böhme] (London: J. Downing, 1711), 30.

138 Germann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica”, 87.

139 Ziegenbalg to Michael Weitzmann, Tranquebar, 7 October 1709, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 120.

140 Ziegenbalg to Joachim Lange, Tranquebar, 23 October 1709, in ibid., 143.

141 Germann, “Bibliotheca Malabarica”, 83. cf.

Ziegenbalg’s description of Kaṇapati’s father-in-law as a “headman over twenty villages” (Ziegenbalg to Lange, Tranquebar, 23 October 1709, in Lehmann, Alte Briefe, 143).

142 Varukka kōvai is a genre of poems in which a town is celebrated in a series of verses each of which begins with a successive letter of the Tamil alphabet (Zvelebil, Lexicon, s.v. varukka-k kōvai).

143 The others are Kāraṇai viḻupparaiyaṉ vaḷamaṭal (bm 27), Kāyārōṇar ulā (bm 45), Kīḻvēḷūr kalampakam (bm 46), and Varuṇakulātittaṉ maṭal (bm 89).

144 Glenn Yocum, “A Non-Brahman Tamil Saiva Mutt: A Field Study of the Thiruvavaduthurai Adheenam”, in Monastic Life in the Christian and Hindu Traditions: A Comparative Study, ed. Austin B. Creel and Vasudha Narayanan (Lampeter: Edwin Mellon Press, 1990), 268.

145 Zvelebil’s discussion of the literary tradition associated with the maṭams is contained in chapter 10, “Late medieval period (A. D. 1200–1750)” (Kamil V. Zvelebil, Tamil Literature, Handbuch der Orientalistik, Zweite Abteilung, Indien; 2. Bd., 1. Abschnitt (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1975), 198–232.

146 Ebeling (Colonizing the Realm of Words, 57–62) notes the maṭams’connections with Mīṉāṭcicuntaram Piḷḷai, U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar, and Āṟumuka Nāvalar, and their role in educating many other Tamil scholars of the nineteenth century.

147 By far the most detailed study of the two older maṭams and the Tiruppaṉantāḷ maṭam, established in the early eighteenth century, is Koppedrayer’s doctoral thesis (cited above, 13). Parts of this work have been published in a series of articles (“Are Śūdras Entitled to Ride in the Palanquin?”, Contributions to Indian Sociology 25, no. 2 (1991): 191–210; “The Varṇāśramacandrika and the Śūdra’s Right to Preceptorhood: The Social Background of a Philosophical Debate in Late Medieval South India”, Journal of Indian Philosophy 19, no. 3 (1991): 297–314; “Remembering Tirumālikaittēvar: The Relationship between an Early Śaiva Mystic and a South Indian Matam”, East and West 43, nos. 1–4 (1993): 169–83; “Putting the Picture Together: Ati Amāvācai at Dharmapuram”, East and West 49, nos. 1–4 (1999): 195–216; “The Interweave of Place, Space, and Biographical Discourse at a South Indian Religious Centre”, in Pilgrims, Patrons, and Place: localizing sanctity in Asian religions, ed. Phyllis Granoffand Koichi Shinohara (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2003), 279–96). In addition there is a helpful study of the contemporary Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai maṭam by Glenn Yocum (“Non-Brahman Tamil Saiva Mutt”). Geoffrey Oddie provides information, drawn from revenue records, about the temples controlled by the maṭams in the nineteenth-century and other information from legal records of disputes between the Tarumapuram and Tiruppaṉantāḷ maṭams (“The Character, Role and Significance of Non-Brahmin Saivite Maths in Tanjore District in the Nineteenth Century”, in Changing South Asia: Religion and Society, ed. Kenneth Ballhatchet and David D. Taylor, vol. 1 (Hong Kong: Published for the Centre of South Asian Studies in the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London, by Asian Research Service, 1984), 37–50, reprinted with some revisions in Hindu and Christian in South-East India (Richmond: Curzon Press, 1991), 98–118). K Nambi Arooran provides brief details about the history of the maṭams in two short articles (“The Origin of Three Saiva Mathas in Tanjavur District”, in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference-Seminar of Tamil Studies, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India, January 1981, ed. M. Arunachalam, vol. 2 (Madras: International Association of Tamil Research, 1981), 12–77–87; “The Changing Role of Three Saiva Maths in Tanjore District from the Beginning of the 20th Century”, in Changing South Asia: Religion and Society, ed. Kenneth Ballhatchet and David D. Taylor, vol. 1 (Hong Kong: Published for the Centre of South Asian Studies in the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London, by Asian Research Service, 1984), 51–58). Ebeling (Colonizing the Realm of Words, 307) cites a recent short history in Tamil of the Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai maṭam (Ci. Makāliṅkam, Tirukkayilāya paramparait Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai ātīṉam varālaṟṟuc curukkam. Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai: Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai ātīṉam Caracuvati Makāl Nūlnilaiya Āyvu Maiyam, 2002).

148 R. Champakalakshmi, “The Maṭha: Monachism as the Base of a Parallel Authority Structure”, in Religion, Tradition, and Ideology: Pre-colonial South India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011), 286–318.

149 Koppedrayer, “Sacred Presence”. Ebeling states that the Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai maṭam “traces its history back to the fourteenth century” (Colonizing the Realm of Words, 61), but this refers only to the lineage of teachers in which the first head of the maṭam, the sixteenth-century Mūvalūr Namacivāyamūrtti, located himself (cf. Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HdO), 206).

150 R. Champakalakshmi provides evidence of the wide range of institutions referred to as maṭam (Champakalakshmi, “The Maṭha”). The institutions at Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai and Tarumapuram may also be referred to using the term ātīṉam, to indicate that they are autonomous. The Tiruppaṉantāḷ maṭam, being subordinate to Tarumapuram, cannot be referred to as an ātīṉam. The use of ātīṉam can be traced only from the eighteenth century, more than a century after their foundation (Koppedrayer, “Sacred Presence”, 11–13).

151 Koppedrayer, “Sacred Presence”, 42–51.

152 Ziegenbalg first uses the term as early as 1707, see below (36).

153 “Asketen und nichbrahmanische [sic] Priester der niedrigen Kasten, oft im Dienst der Śiva-Tempel” (Liebau, Malabarische Korrespondenz, 298). Cf. Gita Dharampal-Frick, “Malabarisches Heidenthum: Bartolomäus Ziegenbalg über Religion und Gesellschaft der Tamilen”, in Missionsberichte aus Indien in 18. Jahrhundert, ed. Michael Bergunder (Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, 1999), 137.

154 Koppedrayer, “Sacred Presence”, 74–75.

155 Ibid., 76–77.

156 See, e.g., Daniel Jeyaraj, Bartholomäus Ziegenbalgs “Genealogie der malabarischen Götter”: Edition der Originalfassung von 1713 mit Einleitung, Analyse und Glossar, Neue Hallesche Berichte: Quelle und Studien zur Geschichte und Gegenwart Südindiens (Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle, 2003), 427, following the Tamil Lexicon and Hobson-Jobson, and Liebau, Malabarische Korrespondenz, 298, cited above, n. 153.

157 Jean Venant Bouchet—a Jesuit contemporary of Ziegenbalg—indicates a further referent of the term when describing the severe austerities undertaken by a Brahmin who “prit la résolution de parcourir le pais en habit de Pandaron [pénitent des Indes], & de s’attirer par l’austérité de sa vie des aumônes abondantes” (Gobien, Lettres édifiantes et curieuses XI, 21).

158 bm 107. Similarly, when commenting on a text he names as Uṭalkuṟṟu tattuvam (bm 99), Ziegenbalg notes that it is “little known and can be understood neither by Brahmins nor by Paṇṭārams”.

159 HB 8: 531.

“Sie antwortet: Hättet ihr unsere Bücher durchlesen, so würdet ihr gantz anders von uns Malabaren und Mohren urtheilen. Ich sprach: Gut, wolt ihr mich als denn besser hören, so will ich gerne die Mühe auf mich nehmen und eure Bücher durchlesen. Lasset mir nur die Besten zu kommen. Sie antwortet: ja, gantz gerne. Darauf ließ ich gleich einen Malabarischen Schreiber ein Verzeichniß von einer ziemlicher Anzahl Bücher aufschreiben, und legte ihnen selbiges vor. Sie sprachen: Wir haben die wenigsten von diesen Büchern; jedoch wollen wir unsern Pantaren, Bramanen, und Schulmeistern Befehl geben, daß sie umher suchen sollen, ob dergleichen ausgeforschet werden können: Unterdessen würde man diejenigen Autores, die solche geschrieben, wieder vom Tode auferwecken müssen, wenn man dergleichen Bücher recht verstehen solte. Ich sagte: Es hat mir dieser Schwierigkeit nichts zu bedeuten. Vielleicht ist anjetzo die Zeit, da sie sollen aufgelöset werden: schaft ihr mir nur fein viele, ich will sie entweder bezahlen, oder mir abschreiben lassen. Sie versprachen mir solches, und nahmen ihren Abschied.”160 Tērūrnta vācakam (BM 77), Tiyākarāca paḷḷu (BM 90). Only the latter is known to be ascribed to Ñānappirakācar in other sources, but Ñānappirakācar is associated with Tiruvārūr, where the former is set. Tarumapuram also administered the “rājan kaṭṭaḷai” endowment at the Tiruvārūr temple (Rajeshwari Ghose, The Lord of Ārūr. The Tyāgarāja Cult in Tamiḻnāḍu: A Study in Conflict and Accommodation (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1996), 255).

161 The temple is also linked with the Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai maṭam, in that the liṅkam worshipped by Namaccivāyamūrtti was named Vaidyanātha, Śiva at Vaitīcuvaraṉkōyil (Yocum, “Non-Brahman Tamil Saiva Mutt”, 255).

162 The Amṛtaghaṭeśvara temple in Tirukkaṭavūr, very close to Tranquebar, from which Ziegenbalg had the Apirāmi antāti (BM 25), was also managed by the Tarumapuram maṭam.

163 Thus, e.g., Uḷḷamuṭaiyāṉ (BM 75), which Ziegenbalg links to the paṇṭārams, is ascribed by him to Taṉvantiri, a cittar who is said to dwell at Vaitīcuvaraṉkōyil. More indirectly still, Vīrai Kavirācapaṇṭitar’s Tamil version of the Saundaryalaharī (bm 84), is linked by Zvelebil to the maṭams as “centres of Sanskritization” (Zvelebil, Tamil Literature (HdO), 251).

164 David Dean Shulman, Tamil Temple Myths: Sacrifice and Divine Marriage in the South Indian Śaiva Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 32.

165 Ebeling, Colonizing the Realm of Words, 60. Cutler notes that Mīṉāṭcicuntaram Piḷḷai “conducted classes on the Vaiṣṇava Kamparāmāyaṇam at Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai at the request of Cāminātaiyar and other senior pupils” (Norman Cutler, “Three Moments in the Genealogy of Tamil Literary Culture”, in Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, ed. Sheldon Pollock (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 279).

166 The Institute of Asian Studies has published a catalogue of 1266 manuscripts kept at the Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai maṭam (Shu Hikosaka and G. John Samuel, A Descriptive Catalogue of Palm-Leaf Manuscripts in Tamil, vol. 3 (ed. A. Thasarathan) (Madras: Institute of Asian Studies, 1993)), and has also indexed 481 mss. at the Tarumapuram maṭam, but not yet published the catalogue.

167 Jeyaraj mentions Ziegenbalg’s use of the work, but states that “This book is yet to be identified” (Jeyaraj, Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 330). His account of Ziegenbalg’s use of it is discussed further below (43–44).

168 There are a number of other cases where Ziegenbalg includes parts of larger works under separate headings in his catalogue, and in fact the relationship between these two works had already been noticed in an edition of Ziegenbalg’s catalogue prepared in 1731 by a later missionary Christoph Theodosius Walther. In this edition of the catalogue, there is an annotation, in a smaller hand, to the entry for the Tirikāla cakkaram which reads: “This book is inserted into the following one,” i.e., the Puvaṉa cakkaram (Walther, Bibliotheca Tamulica, 53).

169 Richard H. Davis, Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshiping Śiva in Medieval India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 95.

170 See, e.g., Isabelle Nabokov, Religion Against the Self: An Ethnography of Tamil Rituals (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 72.

171 David Gordon White, The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 61.

172 There is still less reason to think that this work is as early as Tirumantiram; many later works were attributed to Tirumūlar.

173 Zvelebil, Lexicon, s.v. Tirumūlatēvar.

174 E.g., Pañcākkara taricaṉam, Pañcākkara paḵṟoṭai, Pañcākkara paṟṟiya viḷakkam, Pañcākkara mālai.

175 Ziegenbalg uses the form Nantikēcuran, but the form Nantitēvar is also attested in a manuscript of the Puvaṉa cakkaram in the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library (GOML) in Chennai (tr– 4231).

176 Koppedrayer, “Sacred Presence”, 233.

177 Koppedrayer, “Sacred Presence”, 144.

178 Syed Muhammad Fazlullah Sahib Bahadur and T. Chandrasekharan, A Triennial Catalogue of Tamil Manuscripts Collected during the Trienniums 1934–35 to 1936–37, 1937–38 to 1939–40 and 1940–41 to 1942–43 for the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, Madras, vol. 8. Part 2, Tamil. (Madras: Government of Madras, 1949), 2238–52.

179 Jeyaraj, Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 17, citing hb 2: 82 and J. Ferd. [Johannes Ferdinand] Fenger, Geschichte der Trankebarschen Mission nach den Quellen bearbeitet (Grimma: Verlag von J.M. Gebhardt, 1845), 27f.

180 Jeyaraj, Ziegenbalgs “Genealogie”, 286; Jeyaraj, Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 255.

181 Jeyaraj begins his analysis of the Copenhagen ms. of the Genealogia with “Frühe europäische Werke über Indien” (Ziegenbalgs “Genealogie”, 270–76) and only later turns to “Ziegenbalgs Tamilstudium” (Ibid., 280–90).

182 Jeyaraj, Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 199.

183 Catalogo dos livros que se achaõ na bibliotheca da ingreja chamada Jerusalem em Tranquebar (Tranquebar: Na estampa dos Missionarios Reaes de Dennemarck, 1714). Dharampal-Frick writes: “Gewiß war Ziegenbalg bereits als Neuankömmling mit einem Teil der vorliegenden Literatur über Indien vertraut… An Literatur mit thematischem Bezug auf Indien sind dort [in the 1714 catalogue] u.a. Werke von Roger, Baldaeus, Nerreter, Boemus und Langhanß (1705) aufgefürt” (Indien im Spiegel deutscher Quellen der frühen Neuzeit (1500–1750): Studien zu einer interkulturellen Konstellation, Frühe Neuzeit 18 (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1994), 101–2).

184 Abraham Roger, Breviario de religiāo christāo em maniera de dialogo pera ensino dos que tem contadide commungar com a ingreja de Deos. E justamenta passos de Sagrada Escritura que servem pera monstrar que a doutrina n’este breviario contenida esta conforme a Sancta Verdade pello R. P. Abrahao Rogerio (Amsterdam: dos erdeiros de P. Matthysz, 1689). The Biographical Dictionary of the History of Dutch Protestantism identifies this work as a translation, but not the author (Doede Nauta, ed., Biografisch lexicon voor de geschiedenis van het Nederlandse protestantisme, vol. 5 (Kampen: Kok, 2001), 433). The Catalogo dos livros identifies an edition published in Middelburg in 1662, but the earliest edition we have found (in the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek) is an edition published in Amsterdam in 1668.

185 Ziegenbalgs “Genealogie”, 275; Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 199.

186 Ziegenbalgs “Genealogie”, 232; Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 200.

187 Ziegenbalgs “Genealogie”, 278–79; Genealogy of the South Indian Deities, 201–2.

188 For discussion of other texts important for Ziegenbalg’s account of Hinduism, notably those of the cittar, see Will Sweetman, “The Prehistory of Orientalism: Colonialism and the Textual Basis for Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg’s Account of Hinduism”, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 6, no. 2 (2004): 12–38.