Transactions of The Literary Society of Bombay [Excerpt]

With Engravings

1819

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

ADVERTISEMENT.

THE objects for which the Literary Society of Bombay was instituted, are explained in the Discourse of the President, and it is unnecessary to add any thing to what is there stated.

The first meeting of the Society was held on the 26th November 1804, at Parell-house, where Sir James Mackintosh then resided; -- the Discourse which he read on that occasion is prefixed to the present volume. At this meeting the following persons were present:

The Honourable Jonathan Duncan, governor of Bombay.

The Honourable Sir James Mackintosh, knight, recorder of Bombay.

The Right Honourable Viscount Valentia.

General Oliver Nicolls, commander-in-chief at Bombay.

Stuart Moncrieff Threiplond, esq. advocate-general.

Helenus Scott, M.D. first member of the medical board.

William Dowdeswell. esq. barrister-at-law.

Henry Salt, esq. (now consul-general in Egypt).

Lieutenant-colonel Brooks (now military accountant-general at Bombay).

Lieutenant-colonel Joseph Boden, quarter-master-general at Bombay.

Lieutenant-colonel Thomas Charlton Harris, deputy quarter-master general at Bombay.

Charles Forbes, esq.

Robert Drummond, M.D.

Colonel Jasper Nicolls (now quarter-master-general in Bengal).

Major Edward Moor.

George Keir, M.D.

William Erskine, esq.

Sir James Mackintosh was elected President; Charles Forbes, esq. Treasurer; and William Erskine, esq. Secretary of the Society.

One of the earliest objects that engaged the attention of the Society was the foundation of a public library. On the 25th February 1805, a bargain was concluded for the purchase of a pretty extensive library, which had been collected by several medical gentlemen of the Bombay establishment. This collection has since been much enlarged, and is yearly receiving very considerable additions: -- being thrown open with great readiness to all persons, whether members of the Society or not, it has already become of considerable public utility.

The idea of employing several members of the Society in collecting materials for a statistical account of Bombay having occurred to the President, he communicated to the Society a set of “Queries, the answers to which would be contributions towards a statistical account of Bombay,” and offered himself to superintend the whole of the undertaking: it is perhaps to be regretted, that various circumstances prevented the execution of this plan. As these queries may be of service in forwarding any similar projects, they are subjoined in this volume in Appendix A.

Early in the year 1806 it was resolved, on the motion of the President, “That a proposition should be made to the Asiatick Society, to undertake a subscription to create a fund for defraying the necessary expenses of publishing and translating such Sanscrit works as should most seem to deserve an English version; and for affording a reasonable recompense to the translators, where their situation might make it proper.” The letter that was in consequence addressed to the president of that Society, will be found in Appendix B. The Asiatick Society having referred the consideration of the proposed plan to a committee, came to a resolution, in consequence of their report, to publish from time to time, in volumes distinct from the Asiatick Researches, translations of short works in the Sanscrit and other Oriental languages, with extracts and descriptive accounts of books of greater length. The plan of establishing by subscription a particular fund for translation, was regarded as one that could not be successfully proposed.

In the close of the year 1811, the Society suffered a severe loss by the departure of the president, Sir James Mackintosh, for Europe. Robert Steuart, esq. was on the 25th November elected president in his place; and at the same meeting moved “That, as a mark of respect, the late president Sir James Mackintosh should be elected honorary president of the Society,” – a proposition which was unanimously agreed to.

On the 13th February 1812, Brigadier-general Sir John Malcolm was induced, by the universal feelings of regard entertained by the members of the Society towards the honorary president, to move, “That Sir James Mackintosh be requested to sit for a bust to be placed in the Library of the Literary Society of Bombay, as a token of the respect and regard in which he is held by that body.” And the motion being seconded by John Wedderburn, esq. was unanimously agreed to; general Sir John Malcolm having been requested to furnish a copy of his address, for the purpose of its being inserted in the records of the Society. – It is subjoined in Appendix C.

A communication having been made to the Society of an extract of a letter from William Bruce, esq. The East India Company’s resident at Bushire, regarding a disease known among the wandering tribes of Persia, contracted by such as milk the cattle and sheep, and said to be a preventive of the small-pox; -- in order to give as much publicity as possible to the facts which it contains, for the purpose of encouraging further and more minute inquiry by professional men on a subject of so much importance, the extract is subjoined in Appendix D.

On the 31st January 1815, it was agreed, on the motion of Captain Basil Hall of the royal navy, “That the Society should open a museum for receiving antiquities, specimens in natural history, the arts and mythology of the East.” To this museum Captain Hall made a valuable present of specimens in mineralogy from various parts of the East Indies; and reasonable hopes may be indulged that it will speedily be much enriched, and tend in some degree to remove one of the obstacles at present opposed to the study of natural history and mineralogy in this country.

The Society have also to acknowledge repeated valuable presents, chiefly of Oriental books, from the Government of Bombay.

The liberality of Mr. Money, in presenting the Society with a valuable transit instrument, affords some hopes of seeing at no very distant time the foundation of an observatory, the want of which at so considerable a naval and commercial station as Bombay, has long been regretted. The right honourable the Governor in council has shown his willingness to forward a plan, which has the improvement of scientific and nautical knowledge for its object, by recommending to the Court of Directors a communication made on the subject by the Literary Society of Bombay.

On the 27th June 1815, a translation made by Dr. John Taylor from the original Sanscrit of the Lilawati (a treatise on Hindu arithmetic and geometry) was read to the Society. The Lilawati being a work which has frequently been called for by men of science in Europe, and it being desirable, for the sake of accuracy, that it should be printed under the eye of the learned translator, it was resolved that the work should be immediately printed at the expense of the Society, under Dr. Taylor's superintendence; and it has already made considerable progress in its way through the press.

Of the different papers in the following volume it is not necessary that any thing should be said; the author of each, as is understood in such miscellaneous publications, must be answerable for his separate work.

Bombay,

23d September 1815.

Contents:

Discourse at the Opening of the Society. By Sir James Mackintosh, President

I. An account of the Festival of Mamangom, as celebrated on the Coast of Malabar. By Francis Wrede, Esq. (afterwards Baron Wrede.) Communicated by the Honourable Jonathan Duncan.

II. Remarks upon the Temperature of the Island of Bombay during the Years 1803 and 1804. By Major (now Lieutenant Colonel) Jasper Nicholls.

III. Translations from the Chinese of two Edicts: the one relating to the Condemnation of certain Persons convicted of Christianity; and the other concerning the Condemnation of certain Magistrates in the Province of Canton. By Sir George Staunton. With introductory Remarks by the President Sir James Mackintosh.

IV. Account of the Akhlauk-e-Nasiree, or Morals of Nasir, a celebrated Persian System of Ethics. By Lieutenant Edward Frissell of the Bombay Establishment.

V. Account of the Caves in Salsette, illustrated with Drawings of the principal Figures and Caves. By Henry Salt, Esq. (now Consul General in Egypt.)

VI. On the Similitude between the Gipsy and Hindostanee Languages. By Lieutenant Francis Irvine, of the Bengal Native Infantry.

VII. Translations from the Persian, illustrative of the Opinions of the Sunni and Shia Sects of Mahomedans. By Brigadier General Sir John Malcolm, K.C.B.

VIII. A Treatise on Sufism, or Mahomedan Mysticism. By Lieutenant James William Graham, Linguist to the 1st Battalion of the 6th Regiment of Bombay Native Infantry.

IX. Account of the Hill-Fort of Chapaneer in Guzerat. By Captain William Miles, of the Bombay Establishment.

XI. The fifth Sermon of Sadi, translated from the Persian. By James Ross, Esq. of the Bengal Medical Establishment.

XII. Account of the Origin, History, and Manners of the Race of Men called Bunjaras. By Captain John Briggs, Persian Interpreter to the Hyderabad Subsidiary Force.

XIII. An Account of the Parisnath-Gowricha worshipped in the Desert of Parkur; to which are added, a few Remarks upon the present Mode of Worship of that Idol. By Lieutenant James Mackmurdo.

XIV. Observations on two sepulchral Urns found at Bushire in Persia. By William Erskine, Esq.

XV. Account of the Cave-Temple of Elephanta, with a Plan and Drawings of the principal Figures. By William Erskin, Esq.

XVI. Remarks on the Substance called Gez, or Manna, found in Persia and Armenia. By Captain Edward Frederick, of the Bombay Establishment.

XVII. Remarks on the Province of Kattiwar; its Inhabitants, their Manners and Customs. By Lieutenant James Mackmurdo of the Bombay Establishment.

XVIII. Account of the Cornelian Mines in the Neighborhood of Baroach, in a Letter to the Secretary from John Copland, Esq. of the Bombay Medical Establishment.

XIX. Some Account of the Famine in Guzerat in the Years 1812 and 1813, in a Letter to William Erskine, Esq. By Captain James Rivett Carnac, Political Resident at the Court of the Guicawar.

XX. Plan of a Comparative Vocabulary of Indian Languages. By Sir James Mackintosh, President of the Society.

Appendix A. Queries; to which the Answers will be Contributions towards a statistical Account of Bombay.

Appendix B. Letter of the President of the Literary Society of Bombay to the President of the Asiatick Society.

Appendix C. General Malcolm's Speech on moving that Sir James Mackintosh be requested to sit for his Bust.

Appendix D. Extract of a Letter from William Bruce, Esq. Resident at Bushire, to William Erskine, Esq. of Bombay, communicating the Discovery of a Disease in Persia, contracted by such as milk the Cattle and Sheep, and which is a Preventive of the Small Pox.

List of the Members of the Bombay Literary Society.

A Discourse At The Opening of The Literary Society of Bombay

by Sir James Mackintosh, President of the Society.

Read at Parell, 26th November 1804.

From 1818 to 1824 [James Mackintosh] was professor of law and general politics in the East India Company's College at Haileybury.

-- James Mackintosh, by Wikipedia

Gentlemen,

The smallest society, brought together by the love of knowledge, is respectable in the eye of reason; and the feeble efforts of infant literature in barren and inhospitable regions are in some respects more interesting than the most elaborate works and the most successful exertions of the human mind. They prove the diffusion at least, if not the advancement of science; and they afford some sanction to the hope that knowledge is destined one day to visit the whole earth, and in her beneficent progress to illuminate and humanize the whole race of man.

It is therefore with singular pleasure that I see a small but respectable body of men assembled here by such a principle. I hope that we agree in considering all Europeans who visit remote countries, whatever their separate pursuits may be, as detachments from the main body of civilized men, sent out to levy contributions of knowledge as well as to gain victories over barbarism.

When a large portion of a country so interesting as India fell into the hands of one of the most intelligent and inquisitive nations of the world, it was natural to expect that its ancient and present state should at last be fully disclosed. These expectations were indeed for a time disappointed: during the tumult of revolution and war it would have been unreasonable to have entertained them; and when tranquility was established in that country which continues to be the centre of the British power in Asia, it ought not to have been forgotten that every Englishman was fully occupied by commerce, by military service, or by administration; that we had among us no idle public of readers, and consequently no separate profession of writers; and that every hour bestowed on study was to be stolen from the leisure of men often harassed by business, enervated by the climate, and more disposed to seek amusement than new occupation in the intervals of their appointed toils. It is, besides, a part of our national character, that we are seldom eager to display, and not always read to communicate, what we have acquired. In this respect we differ considerably from other lettered nations: our ingenious and polite neighbours on the continent of Europe, -- to whose enjoyment the applause of others seems more indispensable, whose faculties are more nimble and restless, if not more vigorous, than ours, -- are neither so patient of repose nor so likely to be contented with a secret hoard of knowledge. They carry even into their literature a spirit of bustle and parade, -- a bustle indeed which springs from activity, and a parade which animates enterprise, but which are incompatible with our sluggish and sullen dignity. Pride disdains ostentation, scorns false pretensions, despises even petty merit, refuses to obtain the objects of pursujit by flattery or importunity, and scarcely values any praise but that which she has the right to command. Pride, with which foreigners charge us, and which under the name of a sense of dignity we claim for ourselves, is a lazy and unsocial quality; and in these respects, as in most others, the very reverse of the sociable and good-humoured vice of vanity. It is not therefore to be wondered at, if in India our national character, cooperating with local circumstances, should have produced some real and perhaps more apparent inactivity in working the mine of knowledge of which we had become the masters. Yet some of the earliest exertions of private Englishmen are too important to be passed over in silence. The compilation of laws by Mr. Halhed, and the Ayeen Akbaree, translated by Mr. Gladwin, deserve honourable mention. Mr. Wilkins gained the memorable distinction of having opened the treasures of a new learned language to Europe.

But, notwithstanding the merit of these individual exertions, it cannot be denied that the aera of a general direction of the minds of Englishmen in this country towards learned inquiry, was the foundation of the Asiatic Society by Sir William Jones. To give such an impulse to the public understanding is one of the greatest benefits that a man can confer on his fellow men. On such an occasion as the present, it is impossible to pronounce the name of Sir William Jones without feelings of gratitude and reverence. He was among the distinguished persons who adorned one of the brightest periods of English literature. It was no mean distinction to be conspicuous in the age of Burke and Johnson, of Hume and Smith, of Gray and Goldsmith, of Gibbon and Robertson, of Reynolds and Garrick. It was the fortune of Sir William Jones to have been the friend of the greater part of these illustrious men. Without him, the age in which he lived would have been inferior to past times in one kind of literary glory. He surpassed all his contemporaries, and perhaps even the most laborious scholars of the two former centuries, in extent and variety of attainment. His facility in acquiring was almost prodigious, and he possessed that faculty of arranging and communicating his knowledge, which these laborious scholars very generally wanted. Erudition, which in them was often disorderly and rugged, and had something of an illiberal and almost barbarous air, was by him presented to the world with all the elegance and amenity of polite literature. Though he seldom directed his mind to those subjects of which the successful investigation confers the name of a philosopher, yet he possessed in a very eminent degree that habit of disposing his knowledge in regular and analytical order, which is one of the properties of a philosophical understanding. His talents as an elegant writer in verse were among his instruments for attaining knowledge, and a new example of the variety of his accomplishments. In his easy and flowing prose we justly admire that order of exposition and transparency of language which are the most indispensable qualities of style, and the chief excellencies of which it is capable when it is employed solely to instruct. His writings everywhere breathe pure taste in morals as well as in literature; and it may be said with truth, that not a single sentiment has escaped him which does not indicate the real elegance and dignity which pervaded the most secret recesses of his mind. He had lived perhaps too exclusively in the world of learning for the cultivation of his practical understanding. Other men have meditated more deeply on the constitution of society, and have taken more comprehensive views of its complicated relations and infinitely varied interests. Others have therefore often taught sounder principles of political science; but no man more warmly felt, and no author is better calculated to inspire, those generous sentiments of liberty without which the most just principles are useless and lifeless, and which will, I trust, continue to flow through the channels of eloquence and poetry into the minds of British youth.

It has indeed been sometimes lamented that Sir William Jones should have exclusively directed inquiry towards antiquities. But every man must be allowed to recommend most strongly his own favourite pursuits; and the chief difficulty as well as the chief merit is his who first raises the minds of men to the love of any part of knowledge. When mental activity is once roused its direction is easily changed, and the excesses of one writer, if they are not checked by public reason, are corrected by the opposite excesses of his successor. “Whatever withdraws us from the dominion of the senses, whatever makes the past, the distant, and the future, predominate over the present, advances us in the dignity of thinking beings.”

It is not for me to attempt an estimate of those exertions for the advancement of knowledge which have arisen from the example and exhortations of Sir William Jones. In all judgements pronounced on our contemporaries it is so certain that we shall be accused, and so probable that we may be justly accused, of either partially bestowing or invidiously withholding praise, that it is in general better to attempt no encroachment on the jurisdiction of Time, which alone impartially and justly estimates the works of men.

The Myth of Origin and Destiny

Chapter 1: Historicism and the Myth of Destiny

It is widely believed that a truly scientific or philosophical attitude towards politics, and a deeper understanding of social life in general, must be based upon a contemplation and interpretation of human history. While the ordinary man takes the setting of his life and the importance of his personal experiences and petty struggles for granted, it is said that the social scientist or philosopher has to survey things from a higher plane. He sees the individual as a pawn, as a somewhat insignificant instrument in the general development of mankind. And he finds that the really important actors on the Stage of History are either the Great Nations and their Great Leaders, or perhaps the Great Classes, or the Great Ideas. However this may be, he will try to understand the meaning of the play which is performed on the Historical Stage; he will try to understand the laws of historical development. If he succeeds in this, he will, of course, be able to predict future developments. He might then put politics upon a solid basis, and give us practical advice by telling us which political actions are likely to succeed or likely to fail.

This is a brief description of an attitude which I call historicism. It is an old idea, or rather, a loosely connected set of ideas which have become, unfortunately, so much a part of our spiritual atmosphere that they are usually taken for granted, and hardly ever questioned.

I have tried elsewhere to show that the historicist approach to the social sciences gives poor results. I have also tried to outline a method which, I believe, would yield better results.

But if historicism is a faulty method that produces worthless results, then it may be useful to see how it originated, and how it succeeded in entrenching itself so successfully. An historical sketch undertaken with this aim can, at the same time, serve to analyse the variety of ideas which have gradually accumulated around the central historicist doctrine — the doctrine that history is controlled by specific historical or evolutionary laws whose discovery would enable us to prophesy the destiny of man.

Historicism, which I have so far characterized only in a rather abstract way, can be well illustrated by one of the simplest and oldest of its forms, the doctrine of the chosen people. This doctrine is one of the attempts to make history understandable by a theistic interpretation, i.e. by recognizing God as the author of the play performed on the Historical Stage. The theory of the chosen people, more specifically, assumes that God has chosen one people to function as the selected instrument of His will, and that this people will inherit the earth.

In this doctrine, the law of historical development is laid down by the Will of God. This is the specific difference which distinguishes the theistic form from other forms of historicism. A naturalistic historicism, for instance, might treat the developmental law as a law of nature; a spiritual historicism would treat it as a law of spiritual development; an economic historicism, again, as a law of economic development. Theistic historicism shares with these other forms the doctrine that there are specific historical laws which can be discovered, and upon which predictions regarding the future of mankind can be based.

There is no doubt that the doctrine of the chosen people grew out of the tribal form of social life. Tribalism, i.e. the emphasis on the supreme importance of the tribe without which the individual is nothing at all, is an element which we shall find in many forms of historicist theories. Other forms which are no longer tribalist may still retain an element of collectivism [1]; they may still emphasize the significance of some group or collective — for example, a class — without which the individual is nothing at all. Another aspect of the doctrine of the chosen people is the remoteness of what it proffers as the end of history. For although it may describe this end with some degree of definiteness, we have to go a long way before we reach it. And the way is not only long, but winding, leading up and down, right and left. Accordingly, it will be possible to bring every conceivable historical event well within the scheme of the interpretation. No conceivable experience can refute it. [2] But to those who believe in it, it gives certainty regarding the ultimate outcome of human history.

A criticism of the theistic interpretation of history will be attempted in the last chapter of this book, where it will also be shown that some of the greatest Christian thinkers have repudiated this theory as idolatry. An attack upon this form of historicism should therefore not be interpreted as an attack upon religion. In the present chapter, the doctrine of the chosen people serves only as an illustration. Its value as such can be seen from the fact that its chief characteristics [3] are shared by the two most important modern versions of historicism, whose analysis will form the major part of this book — the historical philosophy of racialism or fascism on the one (the right) hand and the Marxian historical philosophy on the other (the left). For the chosen people racialism substitutes the chosen race (of Gobineau's choice), selected as the instrument of destiny, ultimately to inherit the earth. Marx's historical philosophy substitutes for it the chosen class, the instrument for the creation of the classless society, and at the same time, the class destined to inherit the earth. Both theories base their historical forecasts on an interpretation of history which leads to the discovery of a law of its development. In the case of racialism, this is thought of as a kind of natural law; the biological superiority of the blood of the chosen race explains the course of history, past, present, and future; it is nothing but the struggle of races for mastery. In the case of Marx's philosophy of history, the law is economic; all history has to be interpreted as a struggle of classes for economic supremacy. The historicist character of these two movements makes our investigation topical. We shall return to them in later parts of this book. Each of them goes back directly to the philosophy of Hegel. We must, therefore, deal with that philosophy as well. And since Hegel [4] in the main follows certain ancient philosophers, it will be necessary to discuss the theories of Heraclitus, Plato and Aristotle, before returning to the more modern forms of historicism.

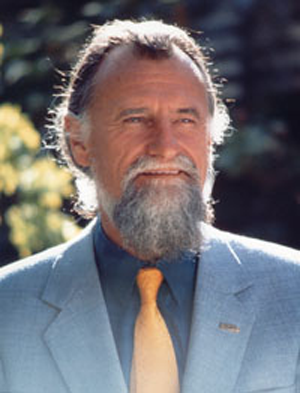

-- The Open Society and Its Enemies, by Karl R. Popper

But it would be unpardonable not to speak of the College at Calcutta, of which the original plan was doubtless the most magnificent attempt ever made for the promotion of learning in the East. I am not conscious that I am biased either by personal feelings or literary prejudices, when I say that I consider that original plan as a wise and noble proposition, of which the adoption in its full extent would have had the happiest tendency to secure the good government of India, as well as to promote the interest of science. Even in its present mutilated state we have seen, at the last public exhibition, Sanscrit declamations by English youth; a circumstance so extraordinary*, [*It must be remembered that this Discourse was read in 1804. In the present year, 1818, this circumstance could no longer be called extraordinary. From the learned care of Mr. Hamilton, late Professor of Indian Languages at the East India College, a proficiency in Sanscrit is become not uncommon in an European Institution.] that, if it be followed by suitable advances, it will mark an epoch in the history of learning.

Appendix II: The College of Fort William in Its Connexion with the East India College, Haileybury.

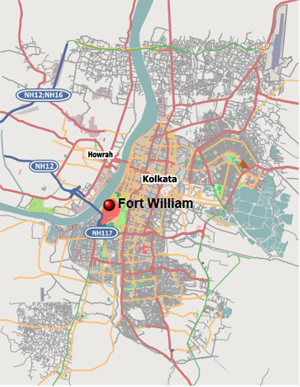

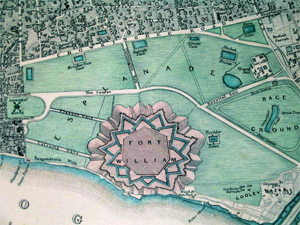

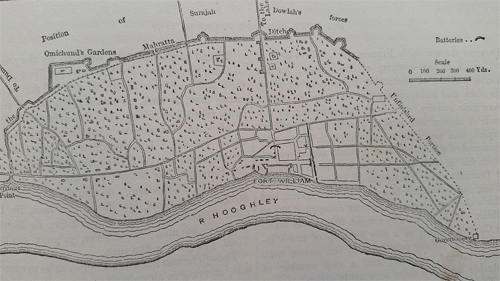

On the 18th of August, 1800, the Marquis Wellesley, Governor-General of India, wrote a minute in Council containing his reasons for establishing a College at Fort William, Calcutta.

It was a long document which, when printed, occupied nearly 43 pages 4to. I subjoin a brief summary: --The age at which writers usually arrive in India [N.B., this was written in 1800] is from sixteen to eighteen. Some of them have been educated with a view to the Indian Civil Service, but on utterly erroneous principles; their education being confined to commercial knowledge and in no degree extended to liberal studies. On arrival in India they are either stationed in the interior, where they ought to be conversant with the languages, laws, and customs of the natives, or they are employed in Government offices where they are chiefly occupied in transcribing papers. Once landed in India their studies, morals, manners, expenses and conduct are no longer subject to any regulation, restraint, or guidance. Hence they often acquire habits destructive to their health and fortunes.

Under these circumstances the General has determined to found a College at Fort William in Bengal for the instruction of the junior Civil Servants in such branches of literature, science, and knowledge as may be deemed necessary to qualify them for the discharge of their duties; and, considering that such a College would be a becoming public monument to commemorate the Conquest of Mysore, he has dated the law for the foundation of the College on the 4th of May, 1800, the first anniversary of the reduction of Seringapatam.

A suitable building is to be erected at Garden Reach. There will be a Provost, Vice-Provost, and a complete staff of Professors both of European and Oriental subjects.1 [1. A list of these was printed. I select the following: -- Provost, Rev. David Brown; Vice-Provost, Rev. C. Buchanan (both of these were Chaplains of the H.E.I.C.S.); Sanskrit and Hindu Law, H.T. Colebrooke; British Law, Sir George Barlow, Bart.; Greek and Latin Classics, Rev. C. Buchanan; Persian, Francis Gladwin; Assistant in Persian and Arabic, Mathew Lumsden; second Assistant in Persian, Capt. Charles Stewart; Sanskrit and Bengali, Rev. William Carey; Hindustani, John Gilchrist.] Statutes are to be drawn up, and all Indian civilians on first arriving in India, even those destined for Bombay and Madras are to be educated at this College, which will be called the College of Fort William.

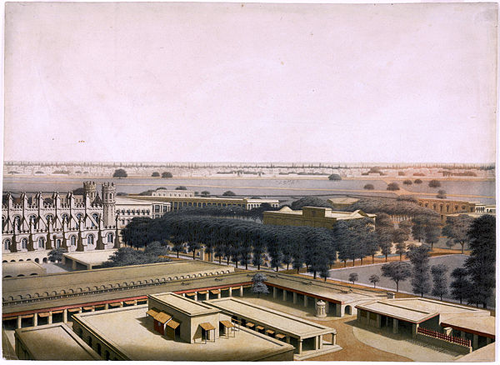

The statutes were promulgated by the first Provost (the Rev. David Brown), on April 10, 1801, and when printed occupied 12 pages 4to. The students were then located in provisional buildings, and the first Disputation in Oriental languages was held on the 6th of February, 1802; a speech being delivered on the occasion by Sir George Barlow, the acting Visitor. All this was done without the knowledge of the Court of Directors in London, who, when they heard of the foundation of the College, passed a resolution against it, on the ground of the enormous and indefinite expenditure which it might involve. They complimented the Marquis on his able minute, and acknowledged the necessity for obtaining a higher class of civil servants by raising the standard of their education and giving them an improved special training, but they only expressed their approbation of part of his plan. In fact a compromise was arranged (see note to line 6 of page 27 of this volume), and it was decided that although the proposed collegiate Building at Garden Reach was not to be erected, an Institution to be called “The East-India College” should be founded in Hertfordshire, which was to give a good general education, combined with instruction in the rudiments of the Oriental languages, while Lord Wellesley’s Institution was to be allowed to continue at Calcutta in a less comprehensive form under the name of Fort William College, with a local habitation in “Writers’ Buildings,” the name given to a long house with good verandahs looking south at the north end of Tank Square (now Dalhousie Square).

It was thus brought about that Fort William College became a kind of continuation of Haileybury, and that its work was restricted to the imparting of fuller instruction in Oriental subjects, the groundwork of which had been laid at Haileybury. And no doubt it was originally intended that all junior civilians who had passed through the Haileybury course should repair to the College in Calcutta for such instruction. Moreover, the process of sifting, which began at Haileybury, was continued at the Forst William Institution. At any rate, it occasionally happened that the worst of those “bad bargains,” which Haileybury, in its too great leniency, had spared, were eliminated from the service at Calcutta.

-- Memorials of Old Haileybury College, by Frederick Charles Danvers, Sir Monier Monier-Williams, Sir Steuart Colvin Bayley, Percy Wigram, Brand Sapte

Among the humblest fruits of this spirit I take the liberty to mention the project of forming this Society, which occurred to me before I left England, but which never could have advanced even to its present state without your hearty concurrence, and which must depend on your active cooperation for all hopes of future success. You will not suspect me of presuming to dictate the nature and object of our common exertions. To be valuable they must be spontaneous; and no literary society can subsist on any other principle than that of equality. In the observations which I shall make on the plan and subject of our inquiries, I shall offer myself to you only as the representative of the curiosity of Europe. I am ambitious of no higher office than that of faithfully conveying to India the desires and wants of the learned at home, and of stating the subjects on which they wish and expect satisfaction, from inquiries which can be pursued only in India. In fulfilling the duties of this mission, I shall not be expected to exhaust so vast a subject, nor is it necessary that I should attempt an exact distribution of science. A very general sketch is all that I can promise; in which I shall pass over many subjects rapidly, and dwell only on those parts on which from my own habits of study I may think myself least disqualified to offer useful suggestions.

The objects of these inquiries, as of all human knowledge, are reducible to two classes, which, for want of more significant and precise terms, we must be content to call Physical and Moral; aware of the laxity and ambiguity of these words, but not affecting a greater degree of exactness than is necessary for our immediate purpose.

The physical sciences afford so easy and pleasing an amusement; they are so directly subservient to the useful arts; and in their higher forms they so much delight our imagination and flatter our pride, by the display of the authority of man over nature, that there can be no need of arguments to prove their utility, and no want of powerful and obvious motives to dispose men to their cultivation. The whole extensive and beautiful science of natural history, which is the foundation of all physical knowledge, has many additional charms in a country where so many treasures must still be unexplored. The science of mineralogy, which has been of late years cultivated with great activity in Europe, has such a palpable connexion with the useful arts of life, that it cannot be necessary to recommend it to the attention of the intelligent and curious. India is a country which I believe no mineralogist has yet examined, and which would doubtless amply repay the labour of the first scientific adventurers who explore it. The discovery of new sources of wealth would probably be the result of such an investigation; and something might perhaps be contributed towards the accomplishment of the ambitious projects of those philosophers, who from the arrangement of earths and minerals have been bold enough to form conjectures respecting the general laws which have governed the past revolutions of our planet, and which preserve its parts in their present order.

The botany of India has been less neglected, but it cannot be exhausted. The higher parts of the science, -- the structure, the functions, the habits of vegetables, -- all subjects intimately connected with the first of physical sciences, though unfortunately the most dark and difficult, the philosophy of life, -- have in general been too much sacrificed to objects of value indeed, but of a value far inferior: and professed botanists have usually contented themselves with observing enough of plants to give them a name in their scientific language and a place in their artificial arrangement. Much information also remains to be gleaned on that part of natural history which regards animals. The manners of many tropical races must have been imperfectly observed in a few individuals separated from their fellows and imprisoned in the unfriendly climate of Europe.

The variations of temperature, the state of the atmosphere, all the appearances that are comprehended under the words weather and climate, are the conceivable subject of a science of which no rudiments yet exist. It will probably require the observations of centuries to lay the foundations of theory on this subject. There can scarce be any region of the world more favourably circumstanced for observation than India; for there is none in which the operation of these causes is more regular, more powerful, or more immediately discoverable in their effect on vegetable and animal nature. Those philosophers who have denied the influence of climate on the human character were not inhabitants of a tropical country.

To the members of the learned profession of medicine, who are necessarily spread over every part of India, all the above inquiries peculiarly though not exclusively belong. Some of them are eminent for science, many must be well informed, and their professional education must have given to all some tincture of physical knowledge. With even moderate preliminary acquirements that may be very useful, if they will but consider themselves as philosophical collectors, whose duty it is never to neglect a favourable opportunity for observations on weather and climate; to keep exact journals of whatever they observe, and to transmit through their immediate superiors to the scientific depositories of Great Britain specimens of every mineral, vegetable, or animal production which they conceive to be singular, or with respect to which they suppose themselves to have observed any new and important facts. If their previous studies have been imperfect, they will no doubt be sometimes mistaken. But these mistakes are perfectly harmless. It is better that ten useless specimens should be sent to London, than that one curious specimen should be neglected.

But it is on another and a still more important subject that we expect the most valuable assistance from our medical associates: this is the science of medicine itself. It must be allowed not to be quite so certain as it is important. But though every man ventures to scoff at its uncertainty as long as he is in vigorous health, yet the hardiest sceptic becomes credulous as soon as his head is fixed to the pillow. Those who examine the history of medicine without either skepticism or blind admiration will find that every civilized age, after all the fluctuations of systems, opinions, and modes of practice, has at length left some balance, however small, of new truth to the succeeding generation, and that the stock of human knowledge in this as well as in other departments is constantly, though it must be owned very slowly, increasing. Since my arrival here I have had sufficient reason to believe that the practitioners of medicine in India are not unworthy of their enlightened and benevolent profession. From them therefore I hope the public may derive, through the medium of this society, information of the highest value. Diseases and modes of cure unknown to European physicians may be disclosed to them; and if the causes of disease are more active in this country than in England, remedies are employed and diseases subdued, at least in some cases, with a certainty which might excite the wonder of the most successful practitioners in Europe. By full and faithful narratives of their modes of treatment they will conquer that distrust of new plans of cure, and that incredulity respecting whatever is uncommon, which sometimes prevail among our English physicians; which are the natural result of much experience and many disappointments; and which, though individuals have often just reason to complain of their indiscriminate application, are not ultimately injurious to the progress of the medical art. They never finally prevent the adoption of just theory or of useful practice. They retard it no longer than is necessary for such a severe trial as precludes all future doubt. Even in their excess they are wholesome correctives of the opposite excess of credulity and dogmatism. They are safeguards against exaggeration and quackery; they are tests of utility and truth. A philosophical physician who is a real lover of his art ought not, therefore, to desire the extinction of these dispositions, though he may suffer temporary injustice from their influence.

Those objects of our inquiries which I have called moral (employing that term in the sense in which it is contradistinguished from physical) will chiefly comprehend the past and present condition of the inhabitants of the vast country which surrounds us.

To begin with their present condition. I take the liberty of very earnestly recommend a kind of research, which has hitherto been either neglected or only carried on for the information of Government. I mean the investigation of those facts which are the subjects of political arithmetic and statistics, and which are a part of the foundation of the science of political economy. The numbers of the people; the number of births, marriages, and deaths; the proportion of children who are reared to maturity; the distribution of the people according to their occupations and casts, and especially according to the great division of agricultural and manufacturing; and the relative state of these circumstances at different periods, which can only be ascertained by permanent tables, -- are the basis of this important part of knowledge. No tables of political arithmetic have yet been made public from any tropical country. I need not expatiate on the importance of the information which such tables would be likely to afford. I shall mention only as an example of their value, that they must lead to a decisive solution of the problems with respect to the influence of polygamy on population, and the supposed origin of that practice in the disproportioned numbers of the sexes*. [See Appendix A. at the end of the Volume.] But in a country where every part of the system of manners and institutions differs from those of Europe, it is impossible to foresee the extent and variety of the new results which an accurate survey might present to us.

These inquiries are naturally followed by those which regard the subsistence of the people; the origin and distribution of public wealth: the wages of every kind of labour, from the rudest to the most refined; the price of commodities, and especially of provisions, which necessarily regulates that of all others; the modes of the tenure and occupation of land; the profits of trade; the usual and extraordinary rates of interest, which are the price paid for the hire of money; the nature and extent of domestic commerce, every where the greatest and most profitable, though the most difficult to be ascertained; those of foreign traffic, more easy to be determined by the accounts of exports and imports: the contributions by which the expenses of Government, of charitable, learned, and religious foundations are defrayed; the laws and customs which regulate all these great objects, and the fluctuation which has been observed in all or any of them at different times and under different circumstances. These are some of the points towards which I should very earnestly wish to direct the curiosity of our intelligent countrymen in India.

These inquiries have the advantage of being easy and open to all men of good sense. They do not, like antiquarian and philological researches, require great previous erudition and constant reference to extensive libraries. They require nothing but a resolution to observe facts attentively, and to relate them accurately. And whoever feels a disposition to ascend from facts to principles, will in general find sufficient aid to his understanding in the great work of Dr. Smith, the most permanent monument of philosophical genius which our nation has produced in the present age.

They have the further advantage of being closely and intimately connected with the professional pursuits and public duties of every Englishman who fills a civil office in this country – they form the very science of administration. One of the first requisites to the right administration of a district is the knowledge of its population, industry, and wealth. A magistrate ought to know the condition of the country which he superintends; a collector ought to understand its revenue; a commercial resident ought to be thoroughly acquainted with its commerce. We only desire that part of the knowledge which they ought to possess should be communicated to the world.

I will not pretend to affirm that no part of this knowledge ought to be confined to Government. I am not so intoxicated by philosophical prejudice as to maintain that the safety of a state is to be endangered for the gratification of scientific curiosity.