by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/9/20

So far as I could make out the trouble had started, as trouble so often does, with gossip, in this case gossip about my relationship with Terry. Dr Edward Conze, who had his own sources of information, later told me that the gossip had originated with 'the old ladies of Kensington', and I had no reason to dispute this. The ladies in question, as I well knew, were a group of some four or five middle-aged women, all of them staunch Theravãdins, who lived in West London and were connected either with the Chiswick Vihara or with the Pali Text Society. Some of them regularly attended the Buddhist Society's annual Summer School, and the gossip seems to have started at the Summer School of 1966, which Terry and I had both attended, and to have reached Walshe not long after our departure for India.

By what means the gossip of the old ladies had reached Walshe, and whether they had gone so far as actually to slander Terry and me, was not clear. What was clear was that Walshe had panicked, as he tended to do in a crisis, that he had called a meeting of the Trust, and that he had proposed that I be dismissed as incumbent of the Hampstead Vihara. Alf Vial and Mike Hookham had, of course, objected to this high-handed and unjust proceeding, and on being out-voted by Walshe, Goulstone, and Marcus, had resigned in protest. Walshe was thus able to assure Humphreys that the trustees had voted for my dismissal unanimously and that, in any case, their action was justified by my behaviour. In these circumstances it was not surprising, perhaps, that Toby [Christmas Humphreys] had agreed, albeit with genuine regret, that it would be better if I did not return to England. Both he and the three remaining trustees evidently assumed that in the absence of any support from either the Sangha Trust or the Buddhist Society, it would be impossible for me to continue my work in England and that I would have no alternative, therefore, but to accept the face-saving formula that Goulstone's letter was shortly to offer me. They assumed, in other words, that I would agree to go quietly, thus enabling the Trust to announce that I had resigned as incumbent of the Hampstead Vihara, and would be staying in the East, without anyone knowing what had really happened.

These tactics having failed, and opposition to my dismissal having steadily grown among members of the Sangha Association, Walshe had dug in his heels, insisting on the Trust's legal right to dismiss me, which was incontestable, and covertly assuring people that I had been dismissed for reasons much more serious than those that had been made public. By the end of the year, however, he had become quite isolated, support for him probably being limited to a few former disciples of Ananda Bodhi. He also seems to have been apprehensive of what might happen once Terry and I were back in England, as we had originally planned. Be that as it may, in January he had agreed to publish in The Buddhist, of which he was now editor, a statement in which the trustees appeared to retract the charges levelled against me in Goulstone's letter. The idea of the statement had originated with Toby, who by this time was ready to dissociate himself from Walshe, and the exact wording had been hammered out in discussions between him and John Hipkin. As published in the February 1967 issue of The Buddhist, shortly before my return to the scene, the statement read as follows:The Directors of the English Sangha Trust Ltd. wish it to be known that in deciding to replace the Ven. Sthavira Sangharakshita in the office of Chief Incumbent at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara they are not making any charge of impropriety or misconduct against him. The Directors hope that whatever may have been said to the detriment of his character in the course of recent speculation and gossip may now be withdrawn, and that all concerned may turn their energies to the study and practice of the Dhamma....

Whatever Walshe's reasons may have been for wanting the trustees' statement published, its appearance in the February Buddhist put him and his fellow trustees in a curious position. On the one hand, they denied that in deciding to replace me they were making any charge of impropriety or misconduct against me; on the other, they continued to resist the Sangha Association's demand for my reinstatement. Indeed, within a month of the statement's publication, Walshe was not only insisting, at the EGM, on the Trust's right to dismiss me, but also repeating the old allegations. Why was he so against me? Was it because I was in favour of closer cooperation between the Sangha Association and the Buddhist Society and he was not? Or was it because I had serious reservations about the insight meditation with which, according to Ruth, his whole emotional security was bound up? Then there was my article 'The Meaning of Orthodoxy in Buddhism: A Protest', serialized in the January, February, and March issues of The Buddhist, in which I ventured to criticize an assertion by Miss I.B. [Isaline Blew] Horner, the President of the Pali Text Society, that the Theravãda was 'certainly the most orthodox form of Buddhism.' Were these the reasons why Walshe was so against me, I asked myself, and so opposed to my reinstatement as incumbent of the Hampstead Vihara? And how big a part had they played in my dismissal? Though Walshe had panicked when the gossip of the old ladies reached him, the gossip and the fact that I was out of the country may well have given him and Goulstone the opportunity to do what they had been wanting to do even before my departure. Had there, then, been a conspiracy to replace me with a Thai monk, and had Vichitr, whom Walshe saw regularly, perhaps been a party to that conspiracy? It was not easy to tell. Events had moved rapidly, a number of people had been involved, and men's real motives were in any case difficult to fathom. Perhaps instead of enquiring too closely into motives I should ask, as the lawyers sometimes did when seeking an explanation for a crime, cui bono? To whose benefit was the crime?

Clues were to be found in the January, February, March, and April issues of The Buddhist, especially in Walshe's editorials. His January editorial was entitled New Beginnings. In Hampstead they had started the New Year with a new incumbent, he announced, after a few generalities, and they would be making a new beginning by going back to the fundamentals of Buddhism, in other words, by going back to the Theravãda. Evidently he believed that during the period of my Incumbency there had been a distinct move in the direction of the Mahãyãna and, to that extent, a move away from the Theravãda. In this there was an element of truth. Though I had regularly lectured on the principal Theravãdin teachings, teachings that were in fact common to all forms of Buddhism, I had not lectured on the Theravãda exclusively. I had also spoken on, or referred to, the teachings of some of the Mahãyãna schools, besides once presenting the Buddhist spiritual path in evolutionary terms. In my meditation classes I had confined myself to teaching respiration-mindfulness (ãnãpãna-sati), and the development of loving-kindness (mettã-bhãvanã), both of which were regarded as Theravãdin methods. Only to the Three Musketeers had I taught any distinctively Mahãyãna (Vajrayãna) practices, and Alf, Mike, and even quiet and unobtrusive Jack may well have been among those whom The Buddhist's new editor described as seeking to run before they can walk, or even to fly before they can run. In his February editorial, entitled 'What is the Sangha?', Walshe was concerned to emphasize two things: that apart from the community of 'Noble Ones' the Sangha consisted exclusively of fully-ordained monks (there was no such thing as a 'lay sangha'), and that, basically, the monks were the preceptors of the lay people and the lay people the supporters of the monks. This was, of course, the traditional Theravãdin position, the rigidity of which I had sought to moderate in my February 1965 editorial entitled 'Sangha and Laity,' and Walshe may have had it in mind when writing his own editorial exactly two years later. In any case, he took occasion to remind the reader that according to one of the rules of the Sangha Association, members should honour their obligations to support the Sangha, by which he meant support it financially on a regular basis, which not all those attending my lectures and classes at the Vihara had been doing.

An announcement elsewhere in the March issue drew the readers attention to other rules. The meetings of the Association were to be concerned solely with the Buddhadhamma; speakers had to have the prior authority of the Sangha; meetings and classes, with the exception of those specifically stated to be public meetings, were to be open only to members of the Association, and members had to produce their membership cards when asked to do so. These rules had fallen into abeyance long before my arrival in Hampstead, and it was obvious why Walshe had decided to reinstate them. He wanted to make it clear that members of the Association should regard themselves as being lay people in the traditional Theravãdin sense, that they should be subordinate to the monks, and that the Association itself should be under the control of the Sangha Trust. An article in the April Buddhist suggested that it was 'back to the Theravãda' at the Biddulph meditation centre too. The article was by John Garrie, a Mancunian 'insight meditation' evangelist whom I had met once or twice, and who was now in charge of activities at Old Hall. In recent months, a programme of decoration and alteration had been completed, he declared towards the end of his article, and in fact Biddulph could well have a sign outside its door saying under new management. As Garrie was a former disciple of Ananda Bodhi, like other members of his team of 'Biddulph enthusiasts,' new management naturally meant Theravãdin management. The team, he moreover went on to say, was the management board of a completely new organization which had no connection with any other society or association and was only responsible to the English Sangha Trust. Thus the Sangha Association was now a Theravãda-type lay body, as was Garrie's team at Biddulph.

To whose benefit, then, was my dismissal as incumbent of the Hampstead Vihara? Evidently it was to the benefit of the Theravãda, or rather, to the benefit of the Theravãdins as represented by Walshe, Goulstone, Vichitr, a minority within the Sangha Association and, no doubt, the old ladies of Kensington.

-- Moving Against the Stream: The Birth of a new Buddhist Movement, by Sangharakshita [Dennis Lingwood]

Isaline Blew Horner, OBE

Born: 30 March 1896, Walthamstow, England

Died: 25 April 1981 (aged 85)

Relatives: Ajahn Amaro [Jeremy Charles Horner] (cousin)

Academic background

Alma mater: Newnham College, Cambridge

Academic work

Discipline: Indologist

Main interests: Pali literature

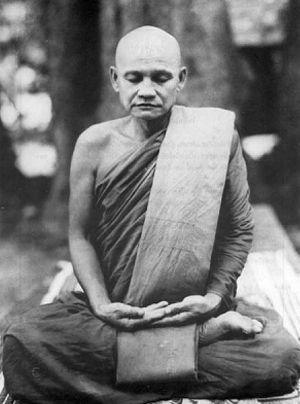

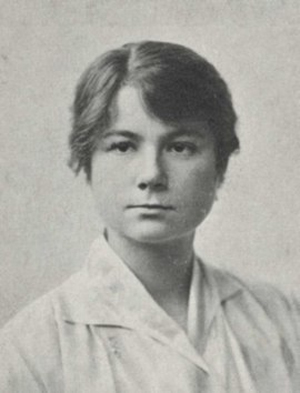

Isaline Blew Horner OBE (30 March 1896 – 25 April 1981), usually cited as I. B. Horner, was an English Indologist, a leading scholar of Pali literature and late president of the Pali Text Society (1959–1981).[1]

Life

On 30 March 1896 Horner was born in Walthamstow in Essex, England. Horner was a first cousin once removed of the British Theravada monk Ajahn Amaro [Jeremy Charles Horner].[2]

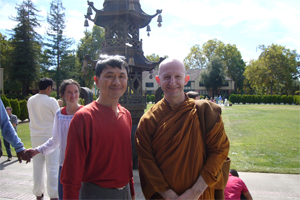

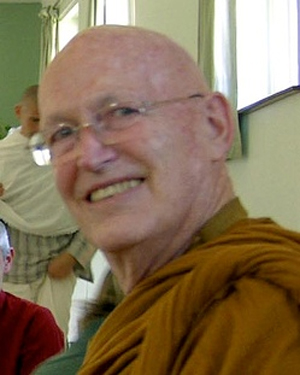

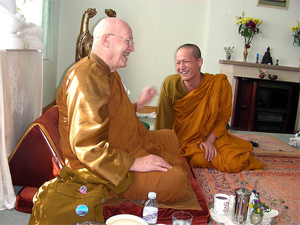

Her Majesty the Queen meeting with Ajahn Amaro, abbot of fAmaravati Monastery, the venerable Bogoda Seelawimala, Head of the London Buddhist Vihara and Dr. Desmond Biddulph, President of the Buddhist Society.

-- The 90th Anniversary of The Buddhist Society 1924–2014, by The Buddhist Society

Cambridge years

In 1917, at the University of Cambridge's women's college Newnham College, Horner was awarded the title of a B.A. in moral sciences.[3][4]

After her undergraduate studies, Horner remained at Newnham College, becoming in 1918 an assistant librarian and then, in 1920, acting librarian. In 1921, Horner traveled to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India and Burma where she was first introduced to Buddhism, its literature and related languages.[5] In 1923, Horner returned to England where she accepted a Fellowship at Newnham College and became its librarian. In 1928, she became the first Sarah Smithson Research Fellow in Pali Studies. In 1930, she published her first book, Women Under Primitive Buddhism. In 1933, she edited her first volume of Pali text, the third volume of the Papancasudani (Majjhima Nikaya commentary). In 1934, Horner was awarded the title of an M.A. from Cambridge. From 1939 to 1949, she served on Cambridge's Governing Body.

From 1926 to 1959, Horner lived and traveled with her companion "Elsie," Dr. Eliza Marian Butler (1885–1959).[6][7][8][9]

Eliza Marian Butler (29 December 1885 – 13 November 1959),who published as E. M. Butler and Elizabeth M. Butler, was an English scholar of German, Schröder Professor of German at the University of Cambridge from 1945. Her most influential book was The Tyranny of Greece over Germany (1935), in which she wrote that Germany has had "too much exposure to Ancient Greek literature and art. The result was that the German mind had succumbed to 'the tyranny of an ideal'. The German worship of Ancient Greece had emboldened the Nazis to remake Europe in their image." It was controversial in Britain and its translation was banned in Germany.

Eliza Butler, known as "Elsie", was born in Bardsea, Lancashire in a family of Irish ancestry. She was educated by a Norwegian governess (from whom she learned German) and subsequently in Hannover from age 11, Paris from age 15, the school of domestic science at Reifenstein Abbey from age 18, and Newnham College, Cambridge from 21. As a teenager, she watched Kaiser Wilhelm II inspect his troops. In the First World War she worked as an interpreter and nurse in Scottish units on the Russian and Macedonian fronts (she had learned Russian from Jane Harrison) and treated the victims of the German assault.Jane Ellen Harrison (9 September 1850 – 15 April 1928) was a British classical scholar and linguist. Harrison is one of the founders, with Karl Kerenyi and Walter Burkert, of modern studies in Ancient Greek religion and mythology. She applied 19th-century archaeological discoveries to the interpretation of ancient Greek religion in ways that have become standard. She has also been credited with being the first woman to obtain a post in England as a ‘career academic’. Harrison argued for women's suffrage but thought she would never want to vote herself. Ellen Wordsworth Crofts, later second wife of Sir Francis Darwin, was Jane Harrison's best friend from her student days at Newnham, and during the period from 1898 to her death in 1903.

Harrison was born in Cottingham, Yorkshire on 9 September 1850 to Charles and Elizabeth Harrison. Her mother died of puerperal fever shortly after she was born and she was educated by a series of governesses. Her governesses taught her German, Latin, Ancient Greek and Hebrew, but she later expanded her knowledge to about sixteen languages, including Russian.

Harrison spent most of her professional life at Newnham College, the progressive, recently established college for women at Cambridge. At Newnham, one of her students was Eugenie Sellers, the writer and poet, with whom she lived in England and later in Paris and possibly even had a relationship with in the late 1880s. Mary Beard described Harrison as '... the first woman in England to become an academic, in the fully professional sense – an ambitious, full-time, salaried, university researcher and lecturer'.

Between 1880 and 1897 Harrison studied Greek art and archaeology at the British Museum under Sir Charles Newton. Harrison then supported herself lecturing at the museum and at schools (mostly private boy's schools). Her lectures became widely popular and 1,600 people ended up attending her Glasgow lecture on Athenian gravestones. She travelled to Italy and Germany, where she met the scholar from Prague, Wilhelm Klein. Klein introduced her to Wilhelm Dörpfeld who invited her to participate in his archaeological tours in Greece. Her early book The Odyssey in Art and Literature then appeared in 1882. Harrison met the scholar D. S. MacColl, who supposedly asked her to marry him and she declined. Harrison then suffered a severe depression and started to study the more primitive areas of Greek art in an attempt to cure herself.

In 1888 Harrison began to publish in the periodical that Oscar Wilde was editing called The Woman's World on "The Pictures of Sappho." Harrison also ended up translating Mythologie figurée de la Grèce (1883) by Maxime Collignon as well as providing personal commentary to selections of Pausanias, Mythology & Monuments of Ancient Athens by Margaret Verrall in the same year. These two major works caused Harrison to be awarded honorary degrees from the universities of Durham (1897) and Aberdeen (1895)...

She became the central figure of the group known as the Cambridge Ritualists. In 1903 her book Prolegomena on the Study of Greek Religion appeared... She then made a new friendship with Hope Mirrlees, whom she referred to as her "spiritual daughter".

Harrison retired from Newnham in 1922 and then moved to Paris to live with Mirrlees. She and Mirrlees returned to London in 1925 where she was able to publish her memoirs through Leonard and Virginia Woolf's press, The Hogarth Press...

Harrison was an atheist...

Harrison's first monograph, in 1882, drew on the thesis that both Homer's Odyssey and motifs of the Greek vase-painters were drawing upon similar deep sources for mythology, the opinion that had not been common in earlier classical archaeology, that the repertory of vase-painters offered some unusual commentaries on myth and ritual.

Her approach in her great work, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1903), was to proceed from the ritual to the myth it inspired: "In theology facts are harder to seek, truth more difficult to formulate than in ritual." Thus she began her book with analyses of the best-known of the Athenian festivals: Anthesteria, harvest festivals Thargelia, Kallynteria [de], Plynteria, and the women's festivals, in which she detected many primitive survivals, Arrophoria, Skirophoria, Stenia and Haloa...

After a socially Darwinian analysis of the origins of religion, Harrison argues that religiosity is anti-intellectual and dogmatic, yet she defended the cultural necessity of religion and mysticism. In her essay The Influence of Darwinism on the Study of Religion (1909), Harrison concluded:

Every dogma religion has hitherto produced is probably false, but for all that the religious or mystical spirit may be the only way of apprehending some things, and these of enormous importance. It may also be that the contents of this mystical apprehension cannot be put into language without being falsified and misstated, that they have rather to be felt and lived than uttered and intellectually analyzed; yet they are somehow true and necessary to life. (176, Alpha and Omega)

-- Jane Ellen Harrison, by Wikipedia

From 1926 to her death Butler lived and travelled with her companion Isaline Blew Horner. After working in hospitals, she taught at Cambridge and in 1936 became a professor at the University of Manchester. Her works include a trilogy on ritual magic and the occult, especially in the Faust legend (1948–1952).

-- Eliza Marian Butler, by Wikipedia

PTS years

In 1936, due to Butler's accepting a position at Manchester University,[8][9] Horner left Newnham to live in Manchester. There, Horner completed the fourth volume of the Papancasudani (published 1937). In 1938, she published the first volume of a translation of the Vinaya Pitaka. (She was to publish a translation of the last Vinaya Pitaka volume in 1966.)

In 1942, Horner became the Honorary Secretary of the Pali Text Society (PTS). In 1943, in response to her parents' needs and greater PTS involvement, Horner moved to London where she lived until her death.[8] In 1959, she became the Society's President[10] and Honorary Treasurer.

Honors

In 1964, in recognition of her contributions to Pali literature, Horner was awarded an honorary Ph.D by Ceylon University.[3][8]

In 1977, Horner received a second honorary Ph.D from Nava Nalanda Mahavihara.[8]

In 1980, Queen Elizabeth II made Horner an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for her lifelong contribution to Buddhist literature.[6][8]

Books

Horner's books (ordered by first identified publication date) include:

• Women under primitive Buddhism : laywomen and almswomen (1930/1975)

• Papañcasūdanī: Majjhimanikāyaṭṭhakathā of Buddhaghosâcariya (1933)

• Early Buddhist theory of man perfected: a study of the Arahan concept and of the implications of the aim to perfection in religious life, traced in early canonical and post-canonical Pali literature (1936/1975)

• Book of the discipline (Vinaya-pitaka) (1938), translated by I. B. Horner

• Alice M. Cooke, a memoir (1940)[11]

• Madhuratthavilāsinī nāma Buddhavaṃsaṭṭhakathā of Bhadantâcariya Buddhadatta Mahāthera (1946/1978), ed. by I.B. Horner.

• Living thoughts of Gotama the Buddha (1948/2001), by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and I.B. Horner

• Collection of the Middle Length Sayings (1954)

• Ten Jātaka stories (1957)

• Early Buddhist poetry (1963)

• Milinda's questions (1963), translated by I. B. Horner

• Buddhist texts through the ages (1964/1990), translated and edited by Edward Conze in collaboration with I.B. Horner, David Snellgrove, Arthur Waley

• Minor anthologies of the Pali Canon (vol. 4): Vimanavatthu and Petavatthu (1974), translated by I. B. Horner

• Minor anthologies of the Pali Canon (vol. 3): Buddhavamsa and Cariyapitaka (1975), translated by I. B. Horner

• Apocryphal birth-stories (Paññāsa Jātaka) (1985), translated by I.B. Horner and Padmanabh S. Jaini

See also

• Pali Text Society

References

1. Olivia, Nona (2014). "Editorial" (PDF). Sati Journal. Sati Center for Buddhist Studies. 2 (1): 3. ISBN 978-1495260049. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

2. Amaro, Ajahn (2014). "I B Horner – Some Biographical Notes" (PDF). Sati Journal. Sati Center for Buddhist Studies. 2 (1): 33–38. ISBN 978-1495260049. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

3. Jayetilleke (2007).

4. At the time, Newnham was one of two women's colleges at Cambridge, the other being Girton College. At Cambridge women were awarded "titles" but not degrees until 1947.

5. Burford 2014, pp. 75-76

6. University of Cambridge (2007).

7. Boucher (2007), p. 121.

8. Burford (2005).

9. Watts (2006).

10. Norman (1982), p. 145

11. Alice M. Cooke. Manchester University Press. 1940.

Sources

• Boucher, Sandy (2007). "Appreciating the Lineage of Buddhist Feminist Scholars", in Rosemary Radford Ruether (ed.) Feminist Theologies (2007). Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-3894-8. Retrieved 2008-08-21 from

• Burford, Grace (2005). "Newnham Biographies: Isaline B. Horner (1896-1981)." Retrieved 2008-08-21 from "Newnham College" at

• Burford, Grace G. (2014). Isaline B. Horner and the Twentieth Century Development of Buddhism in the West. In Todd Lewis (ed), Buddhists: Understanding Buddhism Through the Lives of Practitioners. Wiley. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-1-118-32208-6.

• Jayetilleke, Rohan L. (2007). "The pioneer Pali scholar of the West." Retrieved 2008-08-20 from "Associated Newspapers of Ceylon".

• Norman, K.R. (1982). Isaline Blew Horner (1896-1981) (Obituary), Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 5 (2), 145-149

• University of Cambridge (2007). "Isaline Blew Horner (1896-1981), Pali scholar." Retrieved 2008-08-20.

• Watts, Sheila (2006). "Newnham Biographies: Eliza Marian (Elsie) Butler (1885 – 1959)". Retrieved 2008-08-21