by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/20/21

In 1953, shortly after arriving in Delhi, Nehru sent Freda to Burma as the Indian representative of a UNESCO mission. For the first time in her life Freda found herself in a rich and exclusively Buddhist country. The impact was immediate and galvanic. Surrounded by hundreds of pagodas and thousands of monks roaming the streets in saffron robes, she instantly felt she had come home.

“When I set foot on that soil, the Golden Temple, the monks with their begging bowls, suddenly it was déjà vu. Without understanding anything much about Buddhism, I knew. This is The Way, this is what I have been looking for. I saw the whole thing,” she said. Freda was forty-two years old. Her long, diligent quest to find her true spiritual path was finally over. It had taken thirty-eight years, since her first days of sitting in her local church in Derby before school trying to meditate. Curiously, in spite of her remarkable effort and conscientiousness in searching and trying out the world’s great religious traditions, she had never come across Buddhism before, even though the Buddha had been born, taught, and attained enlightenment in India. His message had thrived there for over seven hundred years, until the Mughals invaded in the thirteenth century. They had swept in from the Middle East, destroying the renowned Nalanda University, hailed as the greatest center of learning in Asia, and setting fire to the largest Buddhist library in the ancient world, which allegedly burned for three months. Thousands of Buddhist monks and scholars fled into obscurity in the Himalayan kingdoms, from where Buddhism spread to the Far East and Southeast Asia. From then on, the Buddha was incorporated into the pantheon of Hindu gods and was regarded as a mythological figure.

Burma now boasted some of the most accomplished Buddhist meditation masters on the planet. Freda wasted no time seeking them out. As usual she went straight to the top.

Sayadaw U Thittila Aggamahapandita was vice president of the World Fellowship of Buddhists and spoke excellent English. He agreed to teach Freda personally for eight weeks. The regime was tough and exceptionally rigorous, demanding she be aware of each detail involved in every activity – walking, eating, brushing teeth, putting on shoes, blinking. Every breath was accompanied by awareness. And then awareness itself was watched by awareness….

“I remember Sayadaw U Pandita telling me, ‘If you get a realization, or a flash, it may not be sitting on your meditation cushion in front of an image of the Buddha. It will probably be somewhere you least expect it.”

That’s precisely what happened. Freda had what she called her enlightenment experience “while I was walking with the Commission through the streets of Kyaukme, in northern Burma. Suddenly I saw the flow of things, the meaning and the connection. It was the first real flash of understanding. I can’t explain exactly what it was because it was beyond words. But it opened so many gates and showed me things I’d been trying to find for a very long time,” she explained. She revealed to a few close friends that her Damascene experience had lasted for hours and was accompanied by great bliss.

A window had been opened, a transcendental window giving a glimpse into another reality. The afterschock was dramatic. “We got a phone call back in Delhi that Mummy had collapsed and we had to bring her home from Burma immediately,” says Ranga. “Of course we had no money, so we went around to Nehru and Indira’s house and they provided the plane fare to fetch her home and an ambulance to meet her at the airport.” Continuing her tour was now out of the question.

“When she arrived, it was shocking. Mummy didn’t recognize anyone. For weeks she stayed in her bed, getting up just to go to the bathroom. That’s as far as she would go. She wouldn’t talk or register anything in the outside world. She’d eat the food put in front of her like an automaton. If you looked at her, it was like looking into a stone wall. She never saw you. It was as though she were catatonic. It was terrifying for all of us – except Papa. He didn’t seem concerned at all. He said it was all happening as it should and that it would work out all right. He was correct. After about six weeks she began to show signs of improvement. Her face became more expressive and she began to interact with us. But it took about three months before she was back to normal.”

Gradually she resumed her work and tried to get back to her old life, but she had irrevocably changed. After Burma she was going in a different direction, and nothing was going to be the same. The first to feel the impact was BPL. Their marriage of twenty years had been founded on love, intellectual compatibility, and their shared vision of an independent India. That last job had been completed. Freda knew with certainty that that phase of her life was over. Her heart and her path now belonged to the Buddha.

She calmly sat her husband down and announced, “I’ve been searching all my life, but it’s the Buddhist monks who have been able to show me what it is that I have been looking for. I am a Buddhist from now on – and I have taken a personal vow of a brahmacharya,” she said, referring to the vow of celibacy said to induce spiritual purity and enhance one’s capacity for divine happiness.

BPL took the news remarkably well....

Another reason that BPL took Freda’s news with such equanimity was that his inner life was running along parallel lines. For some time he had been following his own spiritual quest and was undergoing his own enlightenment experience. It bore all the hallmarks of his originality. “He would sit still for hours without moving. He would babble in voices we didn’t understand. He’d go up onto the roof and stand for hours with his arms outstretched toward a shrine of a Sufi saint,” said Kabir. “We called the doctor, but Papa just smiled at him. ‘What I’m going through is beyond you,’ he told him. The doctor nevertheless insisted on examining him. ‘You won’t find a pulse,’ said Papa. He was right. The astonished doctor left.

“Father started going on walks, discovering the graves of Sufi saints in the area, telling us where they were, both marked and unmarked. He started to do automatic writing. Word got out and people started coming to the house with their problems. Papa would listen, then begin writing, and eventually hand them sheets of paper with answers to their troubles on them. In time he became quite a healer and was known as Baba Bedi, the name given to a holy man.”Having lost touch with its glorious heritage of classical scholarship, the Muslim world today is divided in squabbles between two opposing camps, who despite their respective deviations, are both attempting to usurp the right to represent orthodox Islam. The Wahhabis and Salafis are the product of a British strategy to undermine Islamic tradition and create fundamentalism. While the Sufis are their most vocal and articulate critics, rightly pointing out their corruptions, they themselves are part of a similar conspiracy, again with close ties to Western intelligence and the occult.

The New Age movement, following the teachings of a leading disciple of H. P. Blavatsky, believes that the coming of the Age of Aquarius will herald the beginning of world peace and one-world government, headed by the Maitreya, who is said to be awaited also by Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims, though he is known by these believers respectively as Christ, Messiah, the fifth Buddha, Krishna or Imam Mahdi. The New Age’s expectation of the Mahdi awaited by the Muslims has been nurtured through its relationship with Sufism.

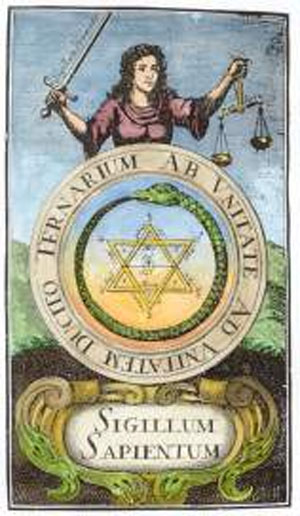

Essentially, the pretext of the occult is that in the future the world will be united in peace by eliminating all sectarianism, when the world will be brought together under a single belief system. The basis of that belief will be the occult tradition, which it is claimed has been the underlying source of all exoteric religions. As such, since at least the middle of the eighteenth century, occultists have marketed Sufism as being the origin of Freemasonry.

According to Idries Shah, the twelfth century Qadiriyya Sufi order was the origin of the Rosicrucians, the most important occult movement after the Renaissance, who later evolved into the Freemasons. As detailed in Black Terror White Soldiers, the Rosicrucians were responsible for orchestrating the advent of Sabbatai Zevi, who took the Jewish world by storm in 1666 when he declared himself their expected messiah. However, Zevi disappointed the vast majority of his followers when he subsequently converted to Islam. Nevertheless, an important segment followed him into Islam as well, and to this day consist of a powerful community of secret Jews known as Dönmeh.

The Dönmeh of Turkey maintained associations with a number of Sufi orders, like Whirling Dervishes founded by Jalal ad-Din Rumi, and the Bektashis. Strongly heretical, the Bektashi venerated Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammed, repudiated many of the legal rulings of Islam, and combined Kabbalistic ideas with elements of ancient Central Asian shamanism.

Through the influence of Bektashi Sufism, the Dönmeh developed the belief of Pan-Turkism, later adopted by the Young Turks, a Dönmeh and Masonic organization responsible for overthrowing the Ottoman Caliphate in 1908. Pan-Turkism begins with Alexander Csoma de Körös (1784 – 1842), the first in the West to mention mysterious Buddhist realm known as Shambhala, which he regarded as the origin of the Turkish people, and which he situated in the Altai mountains and Xinjiang.

Csoma de Körös’s mention of Shambhala became the basis of the mystical speculations offered by H. P. Blavatsky, which she regarded as the homeland of the Aryan race. Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society, and came to be regarded as an oracle of Freemasonry and the godmother of the occult. Blavatsky became largely responsible for initiating the popularity of Buddhism as a font of the Ancient Wisdom. However, contrary to popular perceptions, Tibetan Buddhism is a strange amalgam of Buddhist ideas, along with Hindu Tantra and Central Asian shamanism, it was for this reason that Blavatsky regarded it as the true preservation of the traditions of magic.

-- The Sufi Conspiracy, by David Livingstone

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the first of the hippies and the Beat Generation were arriving in India, and many found their way to BPL’s door. “Then the house got full of really strange people. Papa always made it quite clear to all of them, however, that he was not a saint, nor was he going to behave like one. ‘I’ll smoke my cigarettes and drink my whiskey as normal – and not be bound by anyone,’ Papa said. Gradually he stopped writing automatic messages and started speaking words that he begun coming through him. At first his voice and way of talking were strange, but then the style evolved and he talked like himself,” said Kabir.....

The next event to send shock waves through the family was when Freda, for reasons of her own, sent Guli to boarding school miles away in North India. Her daughter was just five years old. It seemed not only cruel but a terrible dereliction of maternal duty, and out of character with her essentially kind, caring nature. In addition, she performed the deed in what appeared a particularly brutal way.

Guli, now a tall, sociable woman who has dedicated her life to teaching children with special needs, lives in Nashua, New Hampshire, outside Boston, Massachusetts. She recalls every detail of the traumatic event. "When Mummy told me her idea, I told her outright, 'I am not going to boarding school!' We children were all strong characters, who had been taught to speak up. She arranged everything extremely well. We often went touring, and this year Mummy took me to visit an old family friend, Auntie Mera (who had adopted thirteen children) in Naina Tal, in the foothills of Uttar Pradesh. When we got there, she asked if I wanted to see All Saints School, which was nearby and run by Christian nuns. I said yes. I remember the oak tree in the garden, which was huge, and I got very animated and chatty with the nuns. I turned around to tell Mummy something and she was gone. I was absolutely devastated. I cried for three days. The nuns, British Anglican missionaries, were so kind. They really cared for me."

Guli grew to love her school. "It turned out to be the best experience. I studied the scriptures and I know everything about the bible. I loved the hymns and the feeling of the chapel, not that I ever felt the need to become a Christian. There was never any talk about conversion!"....

Whenever she could, she traveled to Burma to continue her meditation training under his strict, watchful eye. Sometimes she took Kabir, her "special child" with her, encouraging him to shave his head and don Buddhist robes as a child monk. Secretly she hoped that one day he would be ordained. That destiny was not to be his, however.

-- The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi, by Vicki Mackenzie

Sarmad Kashani

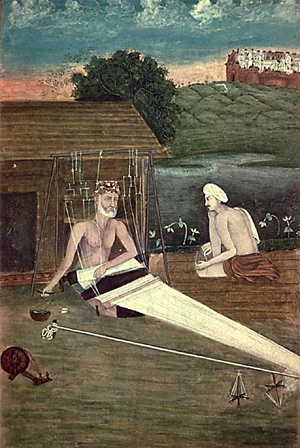

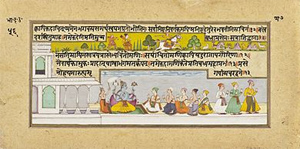

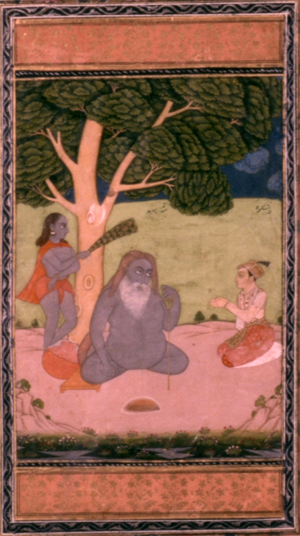

Single Leaf of Shah Sarmad (centre) seated with Shahzada Dara Shikoh

Born: c. 1590, Armenia, Safavid Armenia

Died: 1661, Mughal Empire

School: Sufi

Main interests: Mysticism atheism syncretism poetry Sufi metaphysics

Influences: Mulla Sadra, Mir Findiriski

Influenced: Dara Shukoh, Abul Kalam Azad

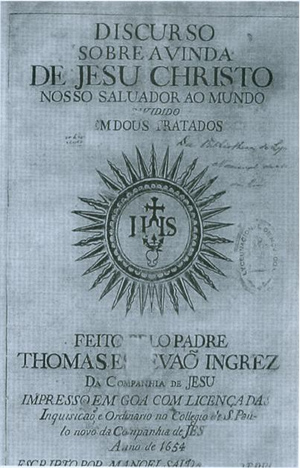

Sarmad Kashani or simply as Sarmad (ca 1590–1661) was a Persian speaking Armenian mystic and poet who travelled to and made the Indian subcontinent his permanent home during the 17th century. Originally Jewish, he may have renounced his religion to adopt Islam.[1] Sarmad, in his poetry, states that he is neither Jewish, nor Muslim, nor Hindu.[2]

Early life

Sarmad was born in Armenia around 1590, to a family of Jewish Persian-speaking Armenian merchants.[3] Sarmad had an excellent command of Persian, essential for his work as a merchant, and composed most of his works in this language.[2] He produced a translation of the Torah in Persian.[4] He studied under Mulla Sadra ...

Mulla Sadra

Ṣadr ad-Dīn Muḥammad Shīrāzī, also called Mullā Ṣadrā (Persian: ملا صدرا; Arabic: صدر المتألهین) (c. 1571/2 – c. 1635/40 CE / 980 - 1050 AH), was a Persian Twelver Shi'i Islamic mystic, philosopher, theologian, and ‘Ālim who led the Iranian cultural renaissance in the 17th century. According to Oliver Leaman, Mulla Sadra is arguably the single most important and influential philosopher in the Muslim world in the last four hundred years.

Though not its founder, he is considered the master of the Illuminationist (or, Ishraghi or Ishraqi) school of Philosophy, a seminal figure who synthesized the many tracts of the Islamic Golden Age philosophies into what he called the Transcendent Theosophy or al-hikmah al-muta’āliyah.Transcendent theosophy or al-hikmat al-muta’āliyah (حكمت متعاليه), the doctrine and philosophy developed by Persian philosopher Mulla Sadra (d.1635 CE), is one of two main disciplines of Islamic philosophy that are currently live and active.

The expression al-hikmat al-muta’āliyah comprises two terms: al-hikmat (meaning literally, wisdom; and technically, philosophy, and by contextual extension theosophy) and muta’āliyah (meaning exalted or transcendent). This school of Mulla Sadra in Islamic philosophy is usually called al-hikmat al-muta’āliyah. It is a most appropriate name for his school, not only for historical reasons, but also because the doctrines of Mulla Sadra are both hikmah or theosophy in its original sense and an intellectual vision of the transcendent which leads to the Transcendent Itself. So Mulla Sadra’s school is transcendent for both historical and metaphysical reasons.

When Mulla Sadra talked about hikmah or theosophy in his words, he usually meant the transcendent philosophy. He gave many definitions to the term hikmah, the most famous one defining hikmah as a vehicle through which “man becomes an intelligible world resembling the objective world and similar to the order of universal existence”.

Mulla Sadra's philosophy and ontology is considered to be just as important to Islamic philosophy as Martin Heidegger's philosophylater was to Western philosophy in the 20th century. Mulla Sadra brought "a new philosophical insight in dealing with the nature of reality" and created "a major transition from essentialism to existentialism" in Islamic philosophy.

A concept that lies at the heart of Mulla Sadra's philosophy is the idea of "existence precedes essence", a key foundational concept of existentialism. This was the opposite of the idea of "essence precedes existence" previously supported by Avicenna and his school of Avicennism as well as Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi and his school of Illuminationism. Sayyid Jalal Ashtiyani later summarized Mulla Sadra's concept as follows: "The existent being that has an essence must then be caused and existence that is pure existence ... is therefore a Necessary Being."

For Mulla Sadra, "existence precedes the essence and is thus principle since something has to exist first and then have an essence." This is primarily the argument that lies at the heart of Mulla Sadra's philosophy. Mulla Sadra substituted a metaphysics of existence for the traditional metaphysics of essences, and giving priority Ab initio to existence over quiddity.

Mulla Sadra effected a revolution in the metaphysics of being by his thesis that there are no immutable essences, but that each essence is determined and variable according to the degree of intensity of its act of existence.

In his view reality is existence, in a variety of ways, and these different ways look to us like essences. What first affects us are things that exist and we form ideas of essences afterward, so existence precedes essence. This position referred to as primacy of existence (Arabic: Isalat al-Wujud).

Mulla Sadra's existentialism is therefore fundamentally different from Western, i.e. existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre said that human beings have no essence before their existence because, there is no Creator, no God. This is the meaning of "existence precedes essence" in Sartre's existentialism.

Another central concept of Mulla Sadra's philosophy is the theory of "substantial motion" (al-harakat al-jawhariyyah), which is "based on the premise that everything in the order of nature, including celestial spheres, undergoes substantial change and transformation as a result of the self-flow (fayd) and penetration of being (sarayan al-wujud) which gives every concrete individual entity its share of being. In contrast to Aristotle and Ibn Sina who had accepted change only in four categories, i.e., quantity (kamm), quality (kayf), position (wad’) and place (‘ayn), Sadra defines change as an all-pervasive reality running through the entire cosmos including the category of substance (jawhar)." Heraclitus described a similar concept centuries earlier (Πάντα ῥεῖ - panta rhei - "everything is in a state of flux"), while Gottfried Leibniz described a similar concept a century after Mulla Sadra's work.

-- Transcendent theosophy, by Wikipedia

Mulla Sadra brought "a new philosophical insight in dealing with the nature of reality" and created "a major transition from essentialism to existentialism" in Islamic philosophy, although his existentialism should not be too readily compared to Western existentialism. His was a question of existentialist cosmology as it pertained to God, and thus differs considerably from the individual, moral, and/or social, questions at the heart of Russian, French, German, or American Existentialism.

Mulla Sadra's philosophy ambitiously synthesized Avicennism, Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi's Illuminationist philosophy, Ibn Arabi's Sufi metaphysics, and the theology of the Sunni Ash'ari school and Shi'a Twelvers.

His main work is The Transcendent Philosophy of the Four Journeys of the Intellect, or simply Four Journeys.

Mulla Sadra was born in Shiraz, in what is now Iran, to a notable family of court officials in 1571 or 1572, In Mulla Sadra's time, the Safavid dynasty governed over Iran. Safavid kings granted independence to Fars Province, which was ruled by the king's brother, Mulla Sadra's father, Khwajah Ibrahim Qavami, who was a knowledgeable and extremely faithful politician. As the ruler of the vast region of Fars Province, Khwajah was rich and held a high position....Sadra was Khwajah's only child. In that time it was customary that the children of aristocrats were educated by private teachers in their own palace. Sadra was a very intelligent, strict, energetic, studious, and curious boy and mastered all the lessons related to Persian and Arabic literature, as well as the art of calligraphy, during a very short time. Following old traditions of his time, and before the age of puberty, he also learned horse riding, hunting and fighting techniques, mathematics, astronomy, some medicine, jurisprudence, and Islamic law. However, he was mainly attracted to philosophy and particularly to mystical philosophy and gnosis.

In 1591, Mulla Sadra moved to Qazvin and then, in 1597, to Isfahan to pursue a traditional and institutional education in philosophy, theology, Hadith, and hermeneutics. At that time, each city was a successive capital of the Safavid dynasty and center of Twelver Shi'ite seminaries. Sadra's teachers included Mir Damad and Baha' ad-Din al-`Amili.

Mulla Sadra became a master of the science of his time. In his own view, the most important of these was philosophy. In Qazvin, Sadra acquired most of his scholarly knowledge from two prominent teachers, namely Baha' ad-Din al-`Amili ...

Shaykh bahaey (right) and Mirfendereski

Bahāʾ al‐Dīn Muḥammad ibn Ḥusayn al‐ʿĀmilī (also known as Sheikh Baha'i, Persian: شیخ بهایی) (18 February 1547 – 1 September 1621) was an Arab Iranian Shia Islamic scholar, philosopher, architect, mathematician, astronomer and poet who lived in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in Safavid Iran. He was born in Baalbek, Ottoman Syria (present-day Lebanon) but immigrated in his childhood to Safavid Iran with the rest of his family. He was one of the earliest astronomers in the Islamic world to suggest the possibility of the Earth's movement prior to the spread of the Copernican theory. He is considered one of the main co-founders of Isfahan School of Islamic Philosophy. In later years he became one of the teachers of Mulla Sadra.

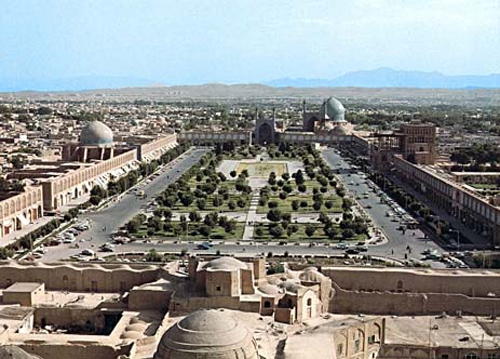

He wrote over 100 treatises and books in different topics, in Arabic and Persian. A number of architectural and engineering designs are attributed to him, but none can be substantiated with sources. These may have included the Naqsh-e Jahan Square and Charbagh Avenue in Isfahan. He is buried in Imam Reza's shrine in Mashad in Iran....

Shaykh Bahāʾī completed his studies in Isfahan. Having intended to travel to Mecca in 1570, he visited many Islamic countries including Iraq, Syria and Egypt and after spending four years there, he returned to Iran...

According to Baháʼí Faith scholar ‘Abdu’l-Hamíd Ishráq-Khávari, Shaykh Baha' al-Din adopted the pen name (takhallus) 'Baha' after being inspired by words of Shi'a Imam Muhammad al-Baqir (the fifth Imam) and Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq (the sixth Imam), who had stated that the Greatest Name of God was included in either Du'ay-i-Sahar or Du'ay-i-Umm-i-Davud. In the first verse of the Du'ay-i-Sahar, a dawn prayer for the Ramadan, the name "Bahá" appears four times: "Allahumma inni as 'aluka min Bahá' ika bi Abháh va kulla Bahá' ika Bahí"...

The following are some his works in astronomy: (1) Risālah dar ḥall‐i ishkāl‐i ʿuṭārid wa qamar (Treatise on the problems of the Moon and Mercury), on attempting to solve inconsistencies of the Ptolemaic system within the context of Islamic astronomy. (2) Tashrīḥ al‐aflāk (Anatomy of the celestial spheres), a summary of theoretical astronomy where he affirms the view that supports the positional rotation of the Earth. He was one of Islamic astronomers to advocate the feasibility of the Earth's rotation in the 16th century, independent of Western influences. (3) Kholasat al-Hesab (The summa of arithmetic) was translated into German by G. H. F. Nesselmann and was published as early as 1843.

Shaykh Baha' al-Din's fame was due to his excellent command of mathematics, architecture and geometry. A number or architectural and engineering designs are attributed to him, but none can be substantiated with sources.

Shaykh Baha' al-Din is also attributed with architectural planning of the city of Isfahan during the Safavid era. He was the architect of Isfahan's Imam Square...

Imam Square

Imam Mosque...

Royal Mosque (Imam Mosque), general view from Naqsh-i Jahan Square — Isfahan.

and Hessar Najaf. He also made a sun clock to the west of the Imam Mosque. There is also no doubt about his mastery of topography. The best instance of this is the directing of the water of the Zayandeh River to different areas of Isfahan. He designed a canal called Zarrin Kamar in Isfahan which is one of Iran's greatest canals. He also determined the direction of Qiblah (prayer direction) from the Naghsh-e-Jahan Square...

Shaykh Baha' al-Din was also an adept of mysticism. He had a distinct Sufi leaning for which he was criticized by Mohammad Baqer Majlesi. During his travels he dressed like a Dervish and frequented Sufi circles. He also appears in the chain of both the Nurbakhshi and Ni'matullāhī Sufi orders. In the work called "Resāla fi’l-waḥda al-wojūdīya" (Exposition of the concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (Unity of Existences), he states that the Sufis are the true believers, calls for an unbiased assessment of their utterances, and refers to his own mystical experiences. His Persian poetry is also replete with mystical allusions and symbols. At the same time, Shaykh Baha' al-Din calls for strict adherence to the Sharia as a prerequisite for embarking on the Tariqah and did not hold a high view of antinomian mysticism.

-- Baha' al-din al-'Amili, by Wikipedia

and Mir Damad, whom he accompanied when the Safavid capital was transferred from Qazvin to Isfahan in 1006 A.H./1596 C.E.Mir Damad (Persian: ميرداماد) (d. 1631 or 1632), known also as Mir Mohammad Baqer Esterabadi, or Asterabadi, was a Twelver Shia Iranian philosopher in the Neoplatonizing Islamic Peripatetic traditions of Avicenna. He also was a Suhrawardi, a scholar of the traditional Islamic sciences, and foremost figure (together with his student Mulla Sadra) of the cultural renaissance of Iran undertaken under the Safavid dynasty. He was also the central founder of the School of Isfahan, noted by his students and admirers as the Third Teacher (mu'alim al-thalith) after Aristotle and al-Farabi.

His major contribution to Islamic philosophy was his novel formulation regarding gradations of time and the emanations of the separate categories of time as descending divine hypostases. He resolved the controversy of the createdness or uncreatedness of the world in time by proposing the notion of huduth-e-dahri (atemporal origination) as an explanation grounded in Avicennan and Suhrawardian categories, whilst transcending them. In brief, excepting God, he argued all things, including the earth and all heavenly bodies, share in both eternal and temporal origination. He influenced the revival of al-falsafa al-yamani (Philosophy of Yemen), a philosophy based on revelation and sayings of prophets rather than the rationalism of the Greeks, and he is widely recognized as the founder of the School of Isfahan, which embraced a theosophical outlook known as hikmat-i ilahi (divine wisdom).

Mir Damad’s many treatises on Islamic philosophy include Taqwim al-Iman (Calendars of Faith, a treasure on creation and divine knowledge), the Kitab Qabasat al-Ilahiyah (Book of the Divine Embers of Fiery Kindling), wherein he lays out his concept of atemporal origination, Kitab al-Jadhawat and Sirat al-Mustaqim. He also wrote poetry under the pseudonym of Ishraq (Illumination). He also wrote a couple of books on mathematics, but with secondary importance.

Among his many other students besides Mulla Sadra were Seyyed Ahmad-ibn-Reyn-al-A’bedin Alavi, Mohammad ibn Alireza ibn Agajanii, Qutb-al-Din Mohammad Ashkevari and Mulla Shams Gilani.

Mir Damad's philosophical prose is often accounted as being among the most dense and obstrusely difficult of styles to understand, deliberately employing as well as coining convoluted philosophical terminology and neologisms that require systematic unpacking and detailed commentary. He was called Mir Damad (Groom of the King) because he married Shah Abbas's daughter and hence his fame was based on that event.

Abbas the Great. Portrait by an unknown Italian painter.

Abbas the Great or Abbas I of Persia (Persian: شاه عباس بزرگ; 27 January 1571 – 19 January 1629) was the 5th Safavid Shah (king) of Iran, and is generally considered as one of the greatest rulers of Persian history and the Safavid dynasty. He was the third son of Shah Mohammad Khodabanda.

Although Abbas would preside over the apex of Iran's military, political and economic power, he came to the throne during a troubled time for the Safavid Empire. Under his weak-willed father, the country was riven with discord between the different factions of the Qizilbash army, who killed Abbas' mother and elder brother. Meanwhile, Iran's enemies, the Ottoman Empire (its archrival) and the Uzbeks, exploited this political chaos to seize territory for themselves. In 1588, one of the Qizilbash leaders, Murshid Qoli Khan, overthrew Shah Mohammed in a coup and placed the 16-year-old Abbas on the throne. However, Abbas soon seized power for himself.

Under his leadership, Iran developed the ghilman system where thousands of Circassian, Georgian, and Armenian slave-soldiers joined the civil administration and the military. With the help of these newly created layers in Iranian society (initiated by his predecessors but significantly expanded during his rule), Abbas managed to eclipse the power of the Qizilbash in the civil administration, the royal house, and the military. These actions, as well as his reforms of the Iranian army, enabled him to fight the Ottomans and Uzbeks and reconquer Iran's lost provinces, including Kakheti whose people he subjected to widescale massacres and deportations. By the end of the 1603–1618 Ottoman War, Abbas had regained possession over Transcaucasia and Dagestan, as well as swaths of Eastern Anatolia and Mesopotamia. He also took back land from the Portuguese and the Mughals and expanded Iranian rule and influence in the North Caucasus, beyond the traditional territories of Dagestan.

Abbas was a great builder and moved his kingdom's capital from Qazvin to Isfahan, making the city the pinnacle of Safavid architecture. In his later years, following a court intrigue involving several leading Circassians, Abbas became suspicious of his own sons and had them killed or blinded.

-- Abbas the Great, by Wikipedia

Mir Damad was also the architect of the Masjide Shah (Shah Mosque) in Isfahan which employed highly advance mathematical calculations which required the knowledge of the speed of sound at that time. The geometry of the dome is as such that all sound dissipated from the base will echo in hundreds of carefully calculated and masterly executed interior corners of the dome which will ultimately collide in the center of the dome. The geometrical analysis of the dome is of absolute sophistication and the design of the dome is a magnificent piece of art and furthermore the construction of such dome in the 17th century to a precision where all sound waves must travel and collide in an imaginary point above.

Royal Mosque (Imam Mosque), general view from Naqsh-i Jahan Square — Isfahan.

-- Mir Damad, by Wikipedia

Shaykh Baha was an expert in Islamic sciences but also a master of astronomy, theoretical mathematics, engineering, architecture, medicine, and some fields of secret knowledge. Mir Damad also knew the science of his time but limited his domain to jurisprudence, hadith, and mainly philosophy. Mir Damad was a master of both the Peripatetic (Aristotelian) and Illuminationist schools of Islamic philosophy. Mulla Sadra obtained most of his knowledge of philosophy and gnosis from Damad and always introduced Damad as his true teacher and spiritual guide.

After he had finished his studies, Sadra began to explore unorthodox doctrines and as a result was both condemned and excommunicated by some Shi'i ʿulamāʾ. He then retired for a lengthy period of time to a village named Kahak, near Qom, where he engaged in contemplative exercises. While in Kahak, he wrote a number of minor works, including the Risāla fi 'l-ḥashr and the Risāla fī ḥudūth al-ʿālam .

In 1612, Ali Quli Khan, son of Allāhwirdī Ḵhān and the powerful governor of Fārs, asked Mulla Sadra to abandon his exile and to come back to Shiraz to teach and run a new madrasa devoted to the intellectual sciences. He died in Basra after the Hajj and was buried in the present-day city of Najaf, Iraq...

Although Existentialism as defined nowadays is not identical to Mulla Sadra's definition, he was the first to introduce the concept. According to Mulla Sadra, "existence precedes the essence and is thus principal since something has to exist first and then have an essence." It is notable that for Mulla Sadra this was an issue that applied specifically to God and God's position in the universe, especially in the context of reconciling God's position in the Qur'an with the Greek-influenced cosmological philosophies of Islam's Golden Era.

Mulla Sadra's metaphysics gives priority to existence over essence (i.e., quiddity). That is to say, essences are variable and are determined according to existential "intensity" (to use Henry Corbin's definition). Thus, essences are not immutable. The advantage to this schema is that it is acceptable to the fundamental statements of the Qur'an, even as it does not necessarily undermine any previous Islamic philosopher's Aristotelian or Platonic foundations.

Indeed, Mulla Sadra provides immutability only to God, while intrinsically linking essence and existence to each other, and to God's power over existence. In so doing, he provided for God's authority over all things while also solving the problem of God's knowledge of particulars, including those that are evil, without being inherently responsible for them — even as God's authority over the existence of things that provide the framework for evil to exist. This clever solution provides for freedom of will, God's supremacy, the infiniteness of God's knowledge, the existence of evil, and definitions of existence and essence that leave the two inextricably linked insofar as humans are concerned, but fundamentally separate insofar as God is concerned.

Perhaps most importantly, the primacy of existence provides the capacity for God's judgement without God being directly, or indirectly, affected by the evil being judged. God does not need to possess sin to know sin: God is able to judge the intensity of sin as God perceives existence.

One result of Sadra's existentialism is "The unity of the intellect and the intelligible" (Arabic: Ittihad al-Aaqil wa l-Maqul. As Henry Corbin describes: "All the levels of the modes of being and perception are governed by the same law of unity, which at the level of the intelligible world is the unity of intellection, of the intelligizing subject, and of the Form intelligized — the same unity as that of love, lover and beloved. Within this perspective we can perceive what Sadra meant by the unitive union of the human soul, in the supreme awareness of its acts of knowledge, with the active Intelligence which is the Holy Spirit. It is never a question of an arithmetical unity, but of an intelligible unity permitting the reciprocity which allows us to understand that, in the soul which it metamorphoses, the Form—or Idea—intelligized by the active Intelligence is a Form which intelligizes itself, and that as a result the active Intelligence or Holy Spirit intelligizes itself in the soul's act of intellection. Reciprocally, the soul, as a Form intelligizing itself, intelligizes itself as a Form intelligized by the active Intelligence...

Mulla Sadra held the view that Reality is Existence. He believed that an essence was by itself a general notion, and therefore and does not, in reality, exist.

To paraphrase Fazlur Rahman on Mulla Sadra's Existential Cosmology: Existence is the one and only reality. Existence and reality are therefore identical. Existence is the all-comprehensive reality and there is nothing outside of it. Essences which are negative require some sort of reality and therefore exist. Existence therefore cannot be denied. Therefore, existence cannot be negated. As Existence cannot be negated, it is self-evident that it Existence is God. God should not be searched for in the realm of existence but is the basis of all existence. Reality in Arabic is "Al-Haq", and is stated in the Qur'an as one of the Names of God.

To paraphrase Mulla Sadra's Logical Proof for God:

1. There is a being

2. This being is a perfection beyond all perfection

3. God is Perfect and Perfection in existence

4. Existence is a singular and simple reality

5. That singular reality is graded in intensity in a scale of perfection

6. That scale must have a limit point, a point of greatest intensity and of greatest existence

7. Therefore, God exists

Sadra argued that all contingent beings require a cause which puts their balance between existence and non-existence in favor of the former; nothing can come into existence without a cause. Since the world is therefore contingent upon this First Act, not only must God exist, but God must also be responsible for this First Act of creation.

Sadra also believed that a causal regress was impossible because the causal chain could only work in the matter that had a beginning, middle, and end:

1) a pure cause at the beginning 2) a pure effect at the end 3) a nexus of cause and effect

The Causal Nexus of Mulla Sadra was a form of Existential Ontology within a Cosmological Framework that Islam supported. For Mulla Sadra the Causal "End" is as pure as its corresponding "Beginning", which instructively places God at both the beginning and the end of the creative act. God's capacity to measure the intensity of Existential Reality by measuring Causal Dynamics' and their Relationship to their Origin, as opposed to knowing their effects, provided the Islamically-acceptable framework for God's Judgement of Reality without being tainted by its Particulars. This was an ingenious solution to a question that had haunted Islamic philosophy for almost one thousand years: How is God able to judge sin without knowing sin?

-- Mulla Sadra, by Wikipedia

and Mir Findiriski before migrating to the Mughal Empire as a merchant.[5]

Mir Fendereski or Mir Findiriski (Persian: میرفِنْدِرِسْکی) (1562–1640) was a Persian philosopher, poet and mystic of the Safavid era. His full name is given as Sayyed Mir Abulqasim Astarabadi (Persian: سید ابولقاسم استرآبادی), and he is famously known as Fendereski. He lived for a while in Isfahan at the same time as Mir Damad, spent a great part of his life in India among yogis and Zoroastrians, and learnt from them. He was patronized by both the Safavid and Mughal courts. The famous Persian philosopher Mulla Sadra also studied under him.

Mir Fendereski remains a mysterious and enigmatic figure about whom we know very little. He was probably born around 1562-1563 and died age of eighty.

Mir Fendereski was trained in the works of Avicenna as he taught the Avicennian medical and philosophical compendiums of al-Qanun (The Canon) and Al-Shifa (The Cure) in Isfahan.

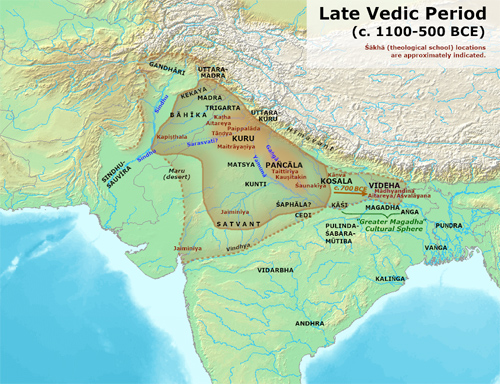

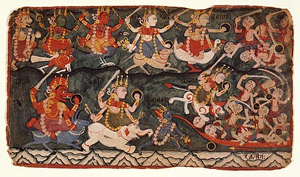

A number of works are attributed to him, although these have not been studied in detail. In his extensive commentary on the Persian translation of the Mahabharata (Razm-Nama in Persian) ...The Mahābhārata (Sanskrit: महाभारतम्, Mahābhāratam, pronounced [mɐɦaːˈbʱaːrɐtɐm]) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kurukshetra War and the fates of the Kaurava and the Pāṇḍava princes and their successors.

It also contains philosophical and devotional material, such as a discussion of the four "goals of life" or puruṣārtha (12.161). Among the principal works and stories in the Mahābhārata are the Bhagavad Gita, the story of Damayanti, the story of Savitri and Satyavan, the story of Kacha and Devyani, the story of Ṛṣyasringa and an abbreviated version of the Rāmāyaṇa, often considered as works in their own right.

Traditionally, the authorship of the Mahābhārata is attributed to Vyāsa. There have been many attempts to unravel its historical growth and compositional layers. The bulk of the Mahābhārata was probably compiled between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century CE, with the oldest preserved parts not much older than around 400 BCE. The original events related by the epic probably fall between the 9th and 8th centuries BCE. The text probably reached its final form by the early Gupta period (c. 4th century CE).

The Mahābhārata is the longest epic poem known and has been described as "the longest poem ever written". Its longest version consists of over 100,000 śloka or over 200,000 individual verse lines (each shloka is a couplet), and long prose passages. At about 1.8 million words in total, the Mahābhārata is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, or about four times the length of the Rāmāyaṇa. W. J. Johnson has compared the importance of the Mahābhārata in the context of world civilization to that of the Bible, the Quran, the works of Homer, Greek drama, or the works of William Shakespeare. Within the Indian tradition it is sometimes called the fifth Veda.

-- Mahabharata, by Wikipedia

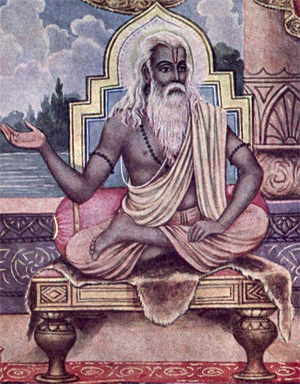

and the philosophical text of the Yoga Vasistha ...Yoga Vasistha (Sanskrit: योग-वासिष्ठ, IAST: Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha) is a philosophical text attributed to Valmiki, although the real author is Vasistha. The complete text contains over 29,000 verses. The short version of the text is called Laghu Yogavasistha and contains 6,000 verses. The text is structured as a discourse of sage Vasistha to Prince Rama. The text consists of six books. The first book presents Rama's frustration with the nature of life, human suffering and disdain for the world. The second describes, through the character of Rama, the desire for liberation and the nature of those who seek such liberation. The third and fourth books assert that liberation comes through a spiritual life, one that requires self-effort, and present cosmology and metaphysical theories of existence embedded in stories.[3] These two books are known for emphasizing free will and human creative power. The fifth book discusses meditation and its powers in liberating the individual, while the last book describes the state of an enlightened and blissful Rama.

Yoga Vasistha teachings are structured as stories and fables, with a philosophical foundation similar to those found in Advaita Vedanta, is particularly associated with drsti-srsti subschool of Advaita which holds that the "whole world of things is the object of mind". The text is notable for expounding the principles of Maya and Brahman, as well as the principles of non-duality, and its discussion of Yoga. The short form of the text was translated into Persian by the 15th-century.

Yoga Vasistha is famous as one of the historically popular and influential texts of Hinduism. Other names of this text are Maha-Ramayana, Arsha Ramayana, Vasiṣṭha Ramayana, Yogavasistha-Ramayana and Jnanavasistha.

-- Yoga Vasistha, by Wikipedia

he complains about the quality of the translation, which implies that he was familiar with Sanskrit. He was among a group of Persians at the Mughal court to engage with Indian thought.

Some of his most famous works are "Resâle Sanaie", "Resâleh dar kimiyâ" and "Šahre ketabe mahârat", in Persian language. He was also a poet and composed a long philosophical ode (qaṣida ḥekmiya) in imitation of and response to the Persian Ismaʿili thinker Nasir Khusraw. His best-known work is titled al-Resāla al-ṣenāʿiya, an examination of the arts and professions within an ideal society. The importance of this treatise is that it combines a number of genres and subject areas: political and ethical thought, mirrors for princes, metaphysics, and the critical subject of the classifications of the sciences.

-- Mir Fendereski, by Wikipedia

Travels in the Mughal Empire

Hearing that precious items and works of art were being purchased in India at high prices, Sarmad gathered together his wares and traveled to the Mughal Empire where he intended to sell them. In Thatta, in present day Sindh, Pakistan, one of his close disciples was a Hindu called Abhay Chand. Although there is debate on the nature of their relationship[6][7] very little is known about the life of Abhay Chand and no historical records to confirm the details of their encounter, except Sarmad's own poetry. Some scholars have argued that, while Sarmad employed Abhay Chand to translate the Torah as well as Old Testament and New Testament, it is possible that Abhay Chand converted to Islam or Judaism.[8] It is important to note that, in later years, Sarmad grew critical of all religions and took a more spiritual position, which is closer to the Sufi tradition.[9]

At some stage, he abandoned his wealth, let his hair grow, stopped clipping his nails and began to wander the city streets.[10] Although it is widely speculated that Sarmad and Abhay Chand moved to Lahore, then to Hyderabad, settling finally in Delhi, however there are no credible sources to confirm the events.

Life in Delhi

The reputation as a poet and mystic he had acquired during the time the two travelled together, caused the Mughal crown prince Dara Shikoh to invite Sarmad at his father's court. On this occasion, Sarmad so deeply impressed the royal heir that he vowed to become his disciple.

Sarmad has been witnessed by the French physician and traveler, François Bernier, who reported Sarmad as a naked faqir.[11]

Death

After the War of Succession with his brother Dara Shikoh, Aurangzeb (1658-1707) emerged victorious, killed his former adversary and ascended the imperial throne. He had Sarmad arrested and tried for heresy. Sarmad was put to death by beheading in 1661.[12][13] His grave is located near the Jama Masjid in Delhi, India.

Sarmad was accused and convicted of atheism and unorthodox religious practice.[14]

Aurangzeb ordered his Ulema to ask Sarmad why he repeated only "There is no God", and ordered him to recite the second part,"but God".[15] To that he replied that "I am still absorbed with the negative part. Why should I tell a lie?" Thus he sealed his death sentence. Ali Khan-Razi, Aurangzeb's court chronicler, was present at the execution. He relates some of the mystic's verses uttered at the execution stand: "The Mullahs say Ahmed went to heaven, Sarmad says that heaven came down to Ahmed." ... "There was an uproar and we opened our eyes from the eternal sleep. Saw that the night of wickedness endured, so we slept again."

Abul Kalam Azad on Sarmad

Abul Kalam Azad, one of the leading political personalities involved in the Indian independence movement, compared himself to Sarmad, for his freedom of thought and expression.[16]

See also

• Dabestan-e Mazaheb

References

1. Prigarina, Natalia. "SARMAD: LIFE AND DEATH OF A SUFI" (PDF). Institute of Oriental Studies, Russia. Retrieved 24 May2016.

2. For some examples of his poetry, see: Poetry Chaikhana Sarmad: Poems and Biography.

3. See mainly: Katz (2000) 148-151. But also: Sarmad the Armenian and Dara Shikoh; Khaleej Times Online - The Armenian Diaspora: History as horror and survival.

4. Fishel, Walter. "Jews and Judaism at the Court of the Mugal Emperors in Medieval India," Islamic Culture, 25:105-31.

5. Puri, Rakshat; Akhtar, Kuldip (1993). "Sarmad, The Naked Faqir". India International Centre Quarterly. 20: 65–78 – via JSTOR.

6. Sikand, Yoginder (2003). Sacred Spaces: Exploring Traditions of Shared Faith in India. Penguin Books India. ISBN 9780143029311.

7. V. N. Datta (27 November 2012), Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Sarman, ISBN 9788129126627, Walderman Hansen doubts whether sensual passions played any part in their love [sic]; puri doubts about their homosexual relationship

8. Goshen-Gottstein, Alon (1 August 2017). The Jewish Encounter with Hinduism: History, Spirituality, Identity. Springer. ISBN 9781137455291.

9. Ridgeon, Lloyd V. J. (2008). Sufism: Hermeneutics and doctrines. Routledge. ISBN 9780415426244.

10. See the account here Archived 2009-04-18 at the Wayback Machine.

11. Bernier, Francois (1996). Travels in the Mogul Empire, AD 1656-1668. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120611696.

12. For the motivations behind his trial as well as a detailed explanation of proceedings, see: Katz (2000) 151-153.

13. Cook 2007.

14. "Votary of freedom: Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Sarmad". Tribune India. 7 October 2007.

15. Najmuddin, Shahzad Z. (2005). Armenia: a Resumé: with Notes on Seth's Armenians in India. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-4039-6.

16. Votary of freedom - Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Sarmad by V. N. Datta, Tribune India, 7 October 2007

Bibliography

• Cook, D. (2007) Martyrdom in Islam (Cambridge) ISBN 9780521850407.

• Tr. by Syeda Sayidain Hameed (1991). "The Rubaiyat of Sarmad" (PDF). Indian Council for Cultural Relations.

• Ezekial, I.A. (1966) Sarmad: Jewish Saint of India (Beas) ASIN B0006EXYM6.

• Gupta, M.G. (2000) Sarmad the Saint: Life and Works (Agra) ISBN 81-85532-32-X.

• Katz, N. (2000) The Identity of a Mystic: The Case of Sa'id Sarmad, a Jewish-Yogi-Sufi Courtier of the Mughals in: Numen 47: 142-160.

• Schimmel, A. And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration Of the Prophet In Islamic Piety (Chapel Hill & London).

External resources

• Sarmad, Mohammed Sa'id

• Majid Sheikh, Sarmad the Armenian and Dara Shikoh

• Sarmad, a mystic poet beheaded in 1661