Part 2 of 2

The true religion and the end of the OpticksOne of the strongest indications of this belief in an intimate connection between morality and correct religion was provided by Newton in the small addition he made to the final paragraph in the third English edition of the Opticks in 1721. He now introduced new final words to the book, adding after ‘they would have taught us to worship our true Author and Benefactor’, ‘as their Ancestors did under the Government of Noah and his Sons before they corrupted themselves’. Here, again, the addition is remarkable in its oddity. Newton does not take the opportunity to expatiate upon ‘our true Author and Benefactor’; he does not, for example, choose to add a comment about the ubiquity and omnipotence of God. Instead, he chooses to add another historical comment, about the ancestors of the heathens, including a suggestion that these ancestors ‘corrupted themselves’.

Newton scholars now know that this final, newly added, clause alludes to the reconstructed history of religion which Newton had been developing, largely in secret,35 since the 1680s in his ‘Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’ (Philosophical Origins of Gentile Theology; hereafter referred to as ‘Origines’), and subsequently in his ‘Original of Religions’, ‘History of the Church’ and various other associated manuscript papers.36 Essentially, Newton presented an account of the history of religion in which the true religion was repeatedly corrupted into idolatry. Noah and his sons were entrusted, after the Flood, to restore the true religion originally taught to Adam and Eve. But the Noachian (Newton uses the word ‘Noachide’) version of the true religion was in turn corrupted into idolatry and had to be restored subsequently by Moses. But, as Newton despairingly (or perhaps contemptuously?) pointed out, ‘the world loves to be deceived’,37 and the true religion was corrupted once again. Whereupon, Jesus Christ was sent to restore once more the true original religion. In a projected Chapter 11 of the ‘Origines’, Newton intended to show:

What the true religion of the Noachides was like before it began to be corrupted by the worship of false Gods. And that the Christian religion turned out to be no more true nor less corrupt.38

Effectively, Newton was saying that Christianity, as it had been taught since the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, was not the true religion, but was yet another corrupt idolatrous religion, which was now long overdue for reform.39

As a result of the comparatively new scholarly interest in Newton's religious papers, and their inclusion in the online Newton Project, Newton scholars can now immediately recognize that Newton was alluding at the end of the Opticks to his own ideas on the history of religion. This was definitely not the case, however, for Newton's contemporaries. Although there are clear signs that Newton at least considered preparing some of these researches for the press, in the end he never went public, and the only aspect of these efforts which did see publication was the associated reform of Biblical chronology, which appeared posthumously in his Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728).40 Newton's reference to the ancestors of Noah worshipping their true author and benefactor before they corrupted themselves could not have had any clear and certain meaning for Newton's contemporaries. All Newton's readers would have known straight away what he meant by the four cardinal virtues, say, but nobody could have known to what he was referring with this mention of Noah.

Having said that, it is also worth noting, of course, that this comment about the ancestors of Noah eventually becoming corrupt was not so unusual a reading of sacred history that it would leap off the page to the unengaged reader as an unorthodox peculiarity. It would have been perfectly possible to see this as a fairly anodyne comment about the fortunes of the Judaic religion before the advent of Jesus Christ and Christianity. Indeed, that is presumably how readers have taken it until very recently. It is only with the discovery of Newton's ‘Origines’ and related papers that we now know that Newton had something much more specific in mind in 1721 when he added this comment about the ancestors of Noah corrupting themselves.

So, what was Newton suggesting (albeit in a highly obscure and even opaque way) in his final paragraph of the Opticks? It seems pretty clear from a reading of the ‘Origines’, ‘History of the Church’ and other writings, that Newton believed that the true religion was intimately bound up with correct natural philosophy. Moreover, this intimate association was revealed even in the form of worship, and the places of worship, of the true religion. We can see this, for example, in the heading of Chapter I of the ‘Origines’:

That Pagan Theology was Philosophical, and primarily sought an astronomical and physical understanding of the world system; and that the twelve Gods of the major Nations are the seven Planets together with the four elements and the quintessence Earth.41

As Kenneth Knoespel wrote in 1999:

For Newton … the question was not accommodation between ancient wisdom and Christian revelation but the extent to which natural philosophy provided the fundamental structure for natural religion to such a degree that in the end all religious practice could be shown to be an expression of natural philosophy.42

Knoespel suggests that the ‘Origines’ may have given way to ‘The Original of Religions’ as the focus of Newton's scholarly efforts when he came to believe he could reconstruct the temples of the original religion, the prytanea, and see the altar fires and associated rituals as representations of the cosmos:

And lastly [Newton wrote] as the Tabernacle was contrived by Moses to be a symbol of ye Heavens (as St Paul and Josephus teach), so were ye Prytanea amongst the nations. And as the Tabernacle was a symbol of the heavens, so were the Prytanea amongs ye nations. The whole heavens they reconed to be ye true & real temple of God & therefore that a Prytaneum might deserve ye name of his Temple they framed it so in the fullest manner to represent the whole systeme of the heavens. A point of religion then wch nothing can be more rational.43

So, the architecture of the Temple at Jerusalem, for example, reflected the structure of the universe.44 And when adherents of the original religion worshipped, they did so in a prytaneum which was modelled on the structure of the cosmos.45

This in turn, of course, was related to Newton's scholarly endeavours of the early 1690s, in the so-called ‘Classical Scholia’, to show that the ancients knew the Copernican theory, and even the universal principle of gravitation. It was obviously crucial for Newton's claims that the prytanea should be modelled on the heliocentric cosmos, not on the corrupt and incorrect Aristotelian/Ptolemaic system.46

It would seem, therefore, that what Newton had in mind when he added this final paragraph to the Opticks, first of all in 1706, was to announce his belief that the perfection of natural philosophy would help us to discover and possibly restore the true religion that had been given to mankind in the earliest ages, but had been repeatedly corrupted and restored, and was at that time, in the early eighteenth century, once again corrupt. For Newton, then, moral philosophy depended upon true religion, and the true religion was intimately intertwined with true natural philosophy. It seems, therefore, that he saw himself as contributing to the revival of the true religion by virtue of his success in natural philosophy.

Why did Newton intrude this into the Opticks?The question remains, why did he choose to make an announcement about this (albeit a highly obscure one) in the Opticks? This question is all the more pertinent given that, on earlier occasions when he intended to allude in print to his religious conclusions, the intention was never carried through to publication.

We have already mentioned the Classical Scholia of the early 1690s: which were intended for a second edition of the Principia which never appeared at that time. But even earlier than that, Newton evidently intended to include a brief discussion of his on-going religious research in the first edition of the Principia (1687). Newton had already begun to write the ‘Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’ when Edmund Halley diverted him into writing the Principia. For a while, Newton planned to include as the Third Book of the Principia a more discursive account of its cosmological conclusions, intended to be more accessible to readers who were incapable of following the mathematics in the other books. This third book was to open with a discussion of the preliminary results of Newton's historical research. It appeared in English translation in 1728 as A Treatise of the System of the World.47 Right at the outset, in the second paragraph of the Treatise, Newton linked ancient knowledge of the solar system to ancient places of worship. After describing the heliocentric system, Newton wrote:

This was the philosophy taught of old by Philolaus, Aristarchus of Samos, Plato in his riper years, and the whole sect of the Pythagoreans. And this was the judgement of Anaximander, more ancient than any of them, and of that wise king of the Romans Numa Pompilius; who as a symbol of the figure of the World with the Sun in the center, erected a temple in honour of Vesta, of a round form, and ordained perpetual fire to be kept in the middle of it.48

This research was still in progress (though suspended while Newton worked on the Principia), but temples to Vesta were to figure prominently in subsequent writings. The beginning of ‘The Original of Religions’, written in the early 1690s, reads: ‘The religion most ancient and most generally received by the nations in the first ages was that of the Prytanea or Vestal Temples.’49

It looks as though Newton recognized straight away the links between his new natural philosophy and what he took to be the original religion, and yet he made no public announcement of this until the Optice of 1706, maintaining it in 1718 and finally reinforcing it slightly for the 1721 edition.50 So, what made him break his silence?

All we can do here is speculate. It seems to me that there are four possibilities—two of which I think we can dismiss fairly quickly. First, he may simply have included it as a clear signal to anyone who had pursued the same research and had come to the same conclusions. Newton is renowned for voyaging on strange seas of thought alone, but he would perhaps have been glad of company if a like-minded thinker responded to his signal. So, although he knew the final sentence would pass by the general reader as nothing more than an odd comment about religious history, he perhaps included it in the hope that somebody out there might have followed the same path and reached the same destination. Such a reader, if he or she existed, would perhaps recognize the reference to Noah and his sons as a hint that Newton had developed a reconstruction of the true religion, and would make contact with this fellow traveller.

Alternatively, he might simply have hoped that one of his readers, or better, a number of them, might have written to him to ask what he meant by saying the bounds of moral philosophy would be enlarged by pursuing the same method that Newton had used in natural philosophy. This would provide him with the opportunity to present his ideas in private correspondence and to sound out reactions.

These may have been considerations in Newton's mind, but they seem too casual to have been the real reason to make him add this seemingly incongruous paragraph to the end of his second major work of natural philosophy. Given what seems to modern readers to be such a strange unexpectedness about this ending, surely we need a much more serious reason for Newton to have chosen to end the Opticks this way?

There is one possibility, which although it may seem unpersuasive to modern readers, does seem to fit with what we know of Newton's idiosyncrasies. The clue to this can be seen in Cornelis Schilt's recent paper on Newton's working methods.51 Schilt shows how Newton fully embraced the approach, common among alchemists, that the discoveries of the art of alchemy should only be communicated to adepts. This approach went hand-in-hand with the view that the adept was capable of picking up clues which the non-expert could not possibly fathom.52 We can see this clearly in Newton's description of his ‘New Theory of Light and Colours’, which he had sent to the Royal Society in February 1671/72:

As to ye printng of that letter [the ‘New Theory’] I am satisfied in their [the Fellows'] judgment, or else I should have thought it too straight and narrow for publicke view. I designed it only to those that know how to improve upon hints of things.53

Bearing this in mind, we can turn for help also to Scott Mandelbrote's earlier paper, which like Schilt's, uses a revealing quotation from Newton in its title: ‘a duty of the greatest moment’.54 Mandelbrote points out that Newton's motivation for writing his religious papers may simply have been for his own benefit: ‘His was a voyage of personal discovery.’ And for Newton, whose relationship to God was characterized by a sense of duty, trying to recover the true religion was a matter of duty: ‘Thou seest therefore that this is no idle speculation, no matters of indifferency but a duty of the greatest moment.’55 It is possible, therefore, that Newton felt he at least owed a duty to God to point the way to others to recover the true religion. At one point in the same unpublished work, for example, he urges putative readers: ‘But search the scriptures thy self & that by frequent reading & constant meditation upon what thou readest, & earnest prayer to God to enlighten thine understanding if thou desirest to find the truth.’56

On this reading, Newton decided it was his duty to God to urge others to embark on their own search for the true religion, and correct moral philosophy, by pursuing the methods demonstrated in the Opticks. In doing so, however, he chose to aim his remarks only at ‘those that know how to improve upon hints of things’, and restricted himself to the strange and completely obscure comment at the end of the Opticks. Anything is possible, where Newton's peccadillos are concerned, but there is another reading which seems to me to be more persuasive. The declamation to ‘search the scriptures thyself’ might well have been written with a real readership in mind. After all, the manuscript in which this appears actually begins, just a couple of paragraphs before, with the words:

Having searched after knowledge in the prophetique scriptures, I have thought my self bound to communicate it for the benefit of others, remembring the judgment of him who hid his talent in a napkin.57

The ending of the Opticks might well be seen, therefore, to count as evidence that Newton fully intended, at least at the time that the Optice and the subsequent English editions of 1718 and 1721 appeared, to publish the fruits of his research on the original religion. This seems to follow from the cryptic nature of the passage. Newton might have been expected to say a bit more, to make his meaning more clear, but if he believed he would be in a position to publish his work on religious history fairly soon, he might well have preferred to leave readers of the Opticks wanting more. In fact, there is clear evidence that Newton intended to go into more detail at the end of the 1721 edition of the Opticks.

In a copy of the 1718 edition (which is now in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California) Newton added in manuscript after the closing printed words, ‘our true Author and Benefactor’:

as their ancestors did before they corrupted themselves. For the seven Precepts of the Noachides were originally the moral law of all nations; & the first of them was to have but one supreme Lord God & not to alienate his worship; the second was not to profane his name; & the rest were to abstain from blood or homicide & from fornication, (that is from incest adultery & all unlawful lusts,) & from theft & all injuries, & to be merciful even to bruit beasts, & to set up magistrates for putting these laws in execution. Whence came the moral Philosophy of the ancient Greeks.58

In the end, as we have seen, Newton simply added, ‘as their Ancestors did under the Government of Noah and his Sons before they corrupted themselves’. After all, the long addition he wrote into his copy of the 1718 edition did nothing to show the links between moral philosophy and natural philosophy. Given what had gone just before, the reader might expect an illustration of how correct natural philosophy, or the correct method of natural philosophy, could lead to correct moral philosophy, but Newton's proposed addition did not fulfil this reasonable expectation. Instead of continuing to show how natural philosophy might reveal moral precepts, ‘by the Light of Nature’, Newton simply slipped into a historical account of the original principles of morality. It seems plausible that Newton realized that what he had written did nothing to advance his claim in the earlier part of the paragraph and therefore did not include it in the 1721 edition.

Before thinking better about this, however, Newton had evidently sent a similar new ending to Pierre Coste to include in his French translation of the Opticks, which appeared in 1720:

… ils nous auroient appris à adorer notre suprême Bienfaiteur, le veritable Auteur de notre Etre, comme firent nos premiers Peres avant que d'avoir corrompu leur Esprit & leurs Mœurs: car la Loi Morale qui étoit observée par toutes les Nations, tandis qu'elles vivoient en Chaldée sous la direction de Noé & de ses Enfans, renfermoit le Culte d'un seul Dieu suprême; & la transgression de cet Article fut punissable, longtemps après, devant le Magistrat des Gentils, Job. xxxi. Moyse en ordonna aussi l'observation à tout Estranger qui habitoit parmi les Israëlites. Selon les Juifs, c'est une Loi qui est encore imposée à toutes les Nations de la Terre par les sept Préceptes des Enfants de Noé; & selon les Chrétiens, par les deux grands Commandemens, qui nous enjoignent d'aimer Dieu & notre Prochain: & sans cet Article, la Vertu n'est en effet qu'un vain nom.59

Google translate: … they would have taught us to adore our supreme Benefactor, the true Author of our Being, as our first Fathers did before having corrupted their Spirit and their Morals: for the Moral Law which was observed by all Nations, while they lived in Chaldea under the direction of Noah & his Children, contained the Worship of a single supreme God; & the transgression of this Article was punishable, long after, before the Magistrate of the Gentiles, Job. xxxi. Moses also ordered the observance of it to any foreigner who lived among the Israelites. According to the Jews, it is a Law which is still imposed on all the Nations of the Earth by the seven Precepts of the Children of Noah; & according to the Christians, by the two great Commandments, which enjoin us to love God & our Neighbour: & without this Article, Virtue is indeed only an empty name.

The same failure to show how the light of nature might lead to a better moral philosophy is also true, of course, of the brief comment that he actually did add to the 1721 English edition—it does not illustrate how correct natural philosophy leads to correct religion. It does, however, hint at Newton's beliefs as to where religion went wrong in the past, and thereby succinctly prepares the reader for a following work. The brief comment at the end of the Opticks can perhaps be seen, then, as a bridge linking the Opticks to ‘Of the Church’, which by about 1710, if Matt Goldish is correct, Newton may well have been preparing for publication.60 Rather than detain his readers at the end of the Opticks by giving a fuller account of his historical research, he chose to finish with a provocative and intriguing gesture—fully intending to expand on this in a following work—a work which in the end, as we know, he never did manage to see through the press.

If this is correct, it would seem that by 1706 Newton felt he was approaching the point where he would be ready to publish the results of research in which he had invested so much labour since the 1680s and that this conviction persisted until 1721, when he evidently still believed a publication on the ‘History of the Church’ might be possible. After a number of false starts, in the aborted accessible Book III of the first edition of the Principia, and in the Classical Scholia of the aborted second edition of the same work, Newton finally chose to allude, albeit cryptically, in the Optice and later editions of the Opticks to his unpublished attempts to reconstruct the true original religion and its subsequent fortunes in the history of religion.

ConclusionIt seems clear that by 1706 Newton had come to believe very firmly in what he discerned as the inextricable link between the true natural philosophy and the true religion. His work for the ‘Origines’ and its successors had reached a position by 1706 which convinced Newton of the intimate connection between the true natural philosophy and the true theology. Newton began to write the Opticks in the early 1690s and at that time he could proceed without having to think about anything other than his experimental results and how they should be interpreted. As he delved deeper into the early history of religion, however, he became increasingly convinced that original places of worship were modelled on the universe as God had created it, and that this was just one aspect of an original religion which was ‘Philosophical, and primarily sought an astronomical and physical understanding of the world system’.61 Having discovered (as he no doubt thought of it—discovery, not invention) the crucial importance of natural philosophy in the constitution of the original religion he could not forbear from mentioning this connection when the 1706 Optice went into print. Perhaps Newton, like Kepler, Robert Boyle and other devout natural philosophers, saw himself as a priest of the Book of Nature, and saw it as his duty to emulate the natural philosopher priests of the original religion.62 As he wrote in ‘The Original of Religions’: ‘And thence it was yt ye Priests anciently were above other men well skilled in ye knowledge of ye true frame of Nature & accounted it a great part of their Theology.’63 Be that as it may, I think the final paragraph of the Opticks is a clear and undeniable indicator of the unity of Newton's thought, and his belief in the intimate and inextricable connection between sound natural philosophy and the true religion.64

It is impossible to reach a clear and certain conclusion as to why Newton concluded the Opticks the way he did, but it seems fair to say that if he did not insert it as a pointer to the theme of his next published book, he must have seen it as a duty to God, and to other believers (of the right sort), to hint at what might be discovered about morality and religion by following the same method which was already beginning to perfect ‘natural Philosophy in all its Parts’. Speculative as this may be, one thing is abundantly clear: Newton really did believe that the true religion was intimately related to the true natural philosophy. Although this belief was sincerely believed (we must assume), there was clearly some element of self deception in it. It is hard to see how Newton could have believed that ‘the seven Precepts of the Noachides’, which he held to be ‘originally the moral law of all nations’, and which he obviously became aware of through scriptural and historical research, could have been derived from ‘the Light of Nature’, especially if the light of nature was exemplified by the methods Newton used in the main body of the Opticks, or those used in the Queries. It is one thing to suppose that the form of worship of a ‘philosophical religion’ would have taken place in temples modelled on the heliocentric world system, but it is quite another to claim to be able to infer, from natural principles, what might have been the moral teachings expounded in those temples. The disconnect between these two stages of thinking would have been made more apparent to English readers if Newton had included the extended passage that he wrote by hand at the end of his copy of the 1718 edition, and that was included in the French translation of 1720.

Newton thought better about mentioning the seven precepts of the Noachides and including specific moral teachings in his final paragraph, and so readers were not able to notice the flaw in Newton's thinking. But if he had included the more extended closing paragraph, at least his readers would have had a better idea of the way Newton was actually thinking about these matters (ultimately, in spite of what he tried to imply, a way which was based on a reading of the scriptures rather than on the experimental method). As it was, it is hardly surprising that the immediately succeeding generation should completely miss the significance of the reference to Noah and his sons and should assume instead that what Newton had in mind must have been a moral philosophy that could be established on grounds analogous to those developed in the new ‘experimental philosophy’. The Enlightenment development of moral Newtonianism, however, was a far cry from what Newton himself envisaged when he wrote that ‘the Bounds of Moral Philosophy will be also enlarged’.

AcknowledgementsAn earlier version of this paper was read at a conference on Newton at the Huntington Library, San Marino, in October 2014: ‘All in Pieces? New Insights into the Structure of Newton's Thought’. I am very grateful to the conference organizer, Rob Iliffe, for inviting me to take part. I also wish to thank Mordechai Feingold, Andrew Janiak, Alan Shapiro and especially Scott Mandelbrote and Stephen Snobelen for their helpful comments on my paper. I would like to thank the anonymous referees of the paper, and the Editor, for helping me to improve it.

Footnotes

Notes1 Isaac Newton, Opticks, or a Treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflections and colours of light. The second edition, with additions (W. and J. Innys, London, 1718), p. 382.

2 Newton, Opticks, or a Treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflections and colours of light (Sam Smith and Benjamin Watford, London, 1704), p. 137. Query 16 in this edition is the last of the queries and is shorter than in subsequent editions.

3 Newton, Optice: sive de reflexionibus, refractionibus, inflexionibus & coloribus lucis. Libri tres (Sam Smith and Benjamin Watford, London, 1706), Query 23, p. 348. This is now easily accessible online, thanks to Rob Iliffe and his team's wonderful Newton Project:

http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/.

4 The various drafts of the Queries are now available online at the Newton Project.

5 On the comparatively recent advent of secularization, see Steve Bruce and Tony Glendinning, ‘When was secularization? Dating the decline of the British churches and locating its cause’, Brit. J. Sociol.61, 107–126 (2010); and Callum G. Brown, The death of Christian Britain: understanding secularisation, 1800–2000 (Routledge, London and New York, 2009).

6 Theology and natural philosophy were regarded as distinct and separate disciplines, and their separation was institutionalized in the universities, notwithstanding what Andrew Cunningham argues in his ‘How the Principia got its name; or, taking natural philosophy seriously’, Hist. Sci.29, 377–392 (1991). For correctives to Cunningham's view, see Edward Grant, ‘God and natural philosophy: the late Middle Ages and Sir Isaac Newton’, Early Sci. Med.6, 279–298 (2000); and Peter Dear, ‘Religion, science and natural philosophy: thoughts on Cunningham's thesis’, Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci.32, 377–386 (2001).

7 On Newton's religious studies see, for example, Frank E. Manuel, Isaac Newton, historian (Cambridge University Press, 1963); Manuel, The religion of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 1974); R. S. Westfall, Never at rest: a biography of Isaac Newton (Cambridge University Press, 1980); James E. Force and Richard H. Popkin (eds), The books of nature and Scripture (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1994); Force and Popkin, Newton and religion: context, nature and influence (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1999); Rob Iliffe, Priest of nature: the religious worlds of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 2017). There are also a number of judicious and highly informative papers by Stephen Snobelen, including, for example, ‘To discourse of God: Isaac Newton's heterodox theology and his natural theology’, in Science and dissent in England, 1688–1945 (ed. Paul Wood), pp. 39–65 (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2004), and ‘“The true frame of Nature”: Isaac Newton, heresy and the reformation of natural philosophy’, in Heterodoxy in early modern science and religion (ed. J. H. Brooke and I. Maclean), pp. 223–262 (Oxford University Press, 2005).

8 Religious sentiments are expressed earlier on in Query 31, and in Query 28, but these are concerned with natural theology, or God's relationship to the Creation. These are more typical of the kind of religious comment routinely appearing in contemporary natural philosophical works. The closing words of the Opticks are not concerned with natural theology, and are significantly different in intention—as we shall see shortly.

9 This kind of lack of explanation has recently been exposed as a common practice in Newton's writings, and what is said here can be seen as further support for this analysis. See Cornelis J. (Kees-Jan) Schilt, ‘“To improve upon hints of things”: illustrating Isaac Newton’, Nuncius31, 50–77 (2016).

10 A. Rupert Hall, All was light: an introduction to Newton's Opticks (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1993). Hall does discuss the earlier, natural theological material (pp. 135–138, 150–152) but remains silent about Newton's suggestion that the bounds of moral philosophy may be enlarged. The same is true of R. S. Westfall, op. cit. (note 7).

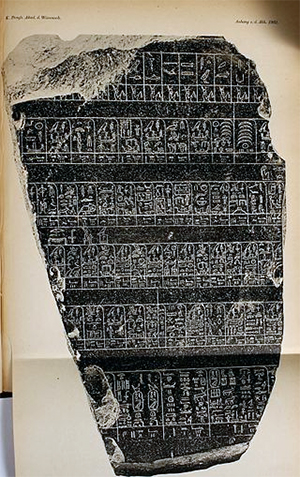

11 Scott Mandelbrote, ‘Newton and eighteenth-century Christianity’, The Cambridge companion to Newton (ed. I. B. Cohen and G. E. Smith), pp. 409–430 (Cambridge University Press, 2002), at p. 421. The significance of Mandelbrote's comment about the religion of Noah will emerge later in this paper. Stephen Snobelen, ‘The true frame of Nature’, op. cit. (note 7). Stephen Snobelen has written a comprehensive account and analysis of all the theological aspects of the different editions of the Opticks, including a detailed analysis of its closing words. But Snobelen discusses the closing words simply for the sake of completeness in his survey of theology in the Opticks. My concern here—why Newton chose to finish the book on just this religious note—is not discussed by Snobelen. Unfortunately, Snobelen's most extensive study remains unpublished: ‘“The Light of Nature”: God and Natural Philosophy in Isaac Newton's Opticks.’ I am very grateful to Dr Snobelen for sending me a copy of this paper, which has proved invaluable. Meanwhile, there are two earlier, shorter versions of the paper in print: Stephen Snobelen, ‘La Lumière de la Nature: Dieu et la philosophie naturelle dans l’Optique de Newton', Lumières4, 65–104 (2004); and ‘“La luz de la Naturaleza”: Dios y filosofia natural en la Óptica de Isaac Newton’, Estudios de Filsofia35, 15–53 (2007). Frank E. Manuel, Isaac Newton, historian, op. cit. (note 7), p. 284, note 23, and plate 10 facing page 117. We return to this manuscript addition to the closing words of the Opticks below.

12 We shall see as the paper proceeds that Newton continually changed the closing words, or thought about changing them, in successive editions. It is perhaps worth adding that A. Rupert Hall mentions that Newton, ‘starting with Optice in 1706’, begins ‘to inject into his scientific writings his system of natural theology’, but he makes no mention of the closing words (which, as we will see, are not concerned with natural theology). A. Rupert Hall, Isaac Newton, adventurer in thought (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 375.

13 Arnold Thackray, Atoms and powers: an essay on Newtonian matter-theory and the development of chemistry (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1970); Robert E. Schofield, Mechanism and materialism: British natural philosophy in an age of reason (Princeton University Press, 1970).

14 Basil Willey, The eighteenth-century background: studies on the idea of nature in the thought of the period (Chatto & Windus, London, 1962), pp. 135–137; Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: an interpretation. Volume II: the science of freedom (Knopf, New York, 1969); Roger L. Emerson, ‘Science and the origins and concerns of the Scottish Enlightenment’, Hist. Sci. 26, 333–366 (1988).

15 George Turnbull, Principles of moral philosophy: an enquiry into the wise and good government of the moral world, 2 vols, vol. I, p. iii (John Noon, London, 1740).

16 David Hume, Treatise of human nature: being an attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects (John Noon, London, 1739). On Hume's Newtonianism see Eric Schliesser, ‘Hume's Newtonianism and anti-Newtonianism’, The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2008 edn, ed. Edward N. Zalta),

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2 ... me-newton/ (accessed 14 May 2016).

17 Hume, Treatise, op. cit. (note 16), Book I, Part I, Section IV.

18 David Hartley, Observations on man, his frame, his duty, and his expectations (James Leake and William Frederick, London, 1749), p. 5.

19 Hartley, op. cit. (note 18), p. 6; and Isaac Newton, The Principia: mathematical principles of natural philosophy (ed. and trans. I. B. Cohen and A. Whitman) (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1999), p. 382.

20 Adam Smith, The wealth of nations, 2 vols (W. Strahan, and T. Cadell, London, 1776). Todd G. Buchholz, From here to economy: a shortcut to economic literacy (Plume, New York, 1996), p. 227; Jerry Evensky, Adam Smith's moral philosophy: a historical and contemporary perspective on markets, law, ethics, and culture (Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 5; Anonymous, ‘Political economy’, Irish Monthly Mag.2, 353 (1846).

21 Adam Smith, ‘The principles which lead and direct philosophical enquiries: illustrated by the history of astronomy’, in Essays on philosophical subjects (ed. W. P. D. Wightman and J. C. Bryce), The Glasgow edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 3, pp. 33–105 (Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 105.

22 Deborah A. Redman, The rise of political economy as a science: methodology and the classical economists (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1997), pp. 207–258. See also, Norriss S. Hetherington, ‘Isaac Newton's influence on Adam Smith's natural laws in economics’, J. Hist. Ideas44, 497–505 (1983); Leonidas Montes, ‘Newton's real influence on Adam Smith and its context’, Camb. J. Econ.32, 555–576 (2008); Eric Schliesser, ‘Some principles of Adam Smith's “Newtonian” methods in the Wealth of Nations’, Research in history of economic thought and methodology23, 35–77 (2005).

23 Paul Hazard, European thought in the eighteenth century (Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1965); Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment: philosophy and the making of modernity 1650–1750 (Oxford University Press, 2002). I say ‘with historical hindsight’—I do not reject claims that the Enlightenment in England was much less irreligious, or anti-religious, than in France, say; but this kind of rationally based morality did in the long run contribute to secularization.

24 John Gascoigne, ‘From Bentley to the Victorians: the rise and fall of British Newtonian natural theology’, Sci. context2, 219–256 (1988); Neal C. Gillespie, ‘Natural history, natural theology and social order: John Ray and the “Newtonian Ideology”’, J. Hist. Biol.20, 1–49 (1987); and Scott Mandelbrote, ‘Early modern natural theologies’, in The Oxford handbook of natural theology (ed. Russell Re Manning), pp. 75–99 (Oxford University Press, 2013).

25 Isaac Newton, Four letters from Sir Isaac Newton to Doctor Bentley containing some arguments in proof of a Deity (R. and J. Dodsley, London, 1756), p. 1. Also available in Isaac Newton, Papers and letters in natural philosophy (ed. I. Bernard Cohen), 2nd edn (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1978), p. 280; and, of course, in Newton, Correspondence (ed. H. W. Turnbull, A. Rupert Hall and Laura Tilling), 7 vols, vol. III (Cambridge University Press, 1959–1977), p. 233.

26 I am referring to the paragraphs in the latest English translation of the Principia, which has now established itself as the standard edition, Isaac Newton, The Principia, op. cit. (note 19), pp. 939–944.

27 Newton, Principia, op. cit. (note 19), p. 940.

28 Newton, Principia, op. cit. (note 19), p. 940.

29 Newton, Principia, op. cit. (note 19), pp. 942–943.

30 Newton, Principia, op. cit. (note 19), pp. 941, 942. The first of these notes, where Newton refers his readers to Edward Pococke (1604–1691) as well as Exodus, Psalms and John, was not added until the 1726 edition; the other note, present in 1713, refers to Cicero, On the nature of the gods; Vergil's Georgics and Aeneid; Philo, Allegorical interpretation; Aratus, Phenomena; and numerous Scriptural citations.

31 Newton, Principia, op. cit. (note 19), p. 943; ‘experimental’ was changed to ‘natural’ for the third (1726) and subsequent editions.

32 Isaac Newton, ‘De gravitatione et aequipondio fluidorum’, in A. Rupert and M. Boas Hall (eds), Unpublished scientific papers of Isaac Newton, pp. 89–156 (Cambridge University Press, 1962). J. A. Ruffner, ‘Newton's De gravitatione: a review and reassessment’, Arch. Hist. Exact Sci.66, 241–264 (2012).

33 Newton, Opticks, op. cit. (note 1), p. 382, emphasis added. In fact, I argue below that there is a flaw in Newton's reasoning here, since we cannot arrive at an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’, as Hume put it. More specifically, no matter what he thinks, Newton cannot legitimately expect moral precepts to emerge from even a complete and certain understanding of the natural world.

34 John Gascoigne, ‘From Bentley to the Victorians: the rise and fall of British Newtonian natural theology’, Sci. context2, 219–256 (1988); Matthew D. Eddy, ‘Nineteenth-century natural theology’, The Oxford handbook of natural theology (ed. Russell Re Manning), pp. 100–118 (Oxford University Press, 2013).

35 Largely, but not entirely; he is known to have discussed some of his ideas on religion with Richard Bentley, David Gregory, Nicholas Fatio de Duillier, John Locke and Samuel Clarke—a handful of people over several decades. A good sense of the uncertainty surrounding Newton's religious beliefs can be gleaned from Scott Mandelbrote, ‘Newton and eighteenth-century Christianity’, op. cit. (note 11).

36 Transcriptions of this and other associated manuscripts are now freely available online via the Newton Project (

http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/). This extraordinary work was first brought to scholarly attention by R. S. Westfall in ‘Newton's theological manuscripts’, in Contemporary Newtonian research (ed. Zev Bechler), pp. 129–144 (D. Reidel, Dordrecht, 1982); ‘Newton's Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’, in The secular mind: transformations of faith in modern Europe (ed. W. Warren Wagar), pp. 15–34 (Holmes & Meier, New York, 1982); and Never at rest, op. cit. (note 7), pp. 351–356. On the ‘History of the Church’, see Matt Goldish, ‘Newton's Of the Church: its contents and implications’, in Newton and religion (ed. Force and Popkin), op. cit. (note 7), pp. 145–164.

37 Newton, ‘Untitled treatise on Revelation’, Section 1.1; Yahuda Ms. 1.1, f. 4r: the Newton Project (note 36).

38 Newton, ‘Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’, Yahuda Ms. 16, f. 43Av. This seems to be the heading for an unwritten Chapter 11: ‘Qualis fuit vera Noachidarum religio antequam per cultum falsorum Deorum corrumpi cæpit. Et quod religio Christiana non magis vera nec minus corrupta evasit.’

39 For Newton, worship of Jesus as an aspect of the Godhead was itself idolatrous. He insisted the true religion was strictly monotheistic, and Trinitarianism was a gross and indefensible corruption. On Newton's anti-Trinitarianism, see Westfall, Never at rest, op. cit. (note 7), especially pp. 312–356; and Stephen Snobelen, ‘Isaac Newton, Socinianism and “The one supreme God”’, Socinianism and cultural exchange: the European dimension of Antitrinitarian and Arminian networks, 1650–1720 (ed. Martin Mulsow and Jan Rohls), pp. 241–298 (Brill, Leiden, 2005). On Newton's belief that a reform of religion was urgently required, see Snobelen, ‘The true frame of Nature’, op. cit. (note 7).

40 Isaac Newton, Chronology of ancient kingdoms amended (J. Tonson, London, 1728). For the background to these studies, see Frank E. Manuel, Isaac Newton, historian, op. cit. (note 7); Jed Z. Buchwald and Mordechai Feingold, Newton and the origin of civilization (Princeton University Press, 2011).

41 Newton, ‘Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’, Yahuda Ms. 16. 2, f. 1r. The original reads: ‘Quod Theologia Gentilis Philosophica erat, et ad scientiam Astronomicam & Physicam systematis mundani apprime spectabat: quodque Dij duodecim majorum Gentium sunt Planetæ septem cum quatuor elementis et quintessentia Terra.’

42 Kenneth Knoespel, ‘Interpretive strategies in Newton's Theologiae gentilis origines philosophiae’, in Newton and religion (ed. Force and Popkin), op. cit. (note 7), pp. 179–202, p. 190.

43 Newton, ‘The original of religions’, Yahuda Ms. 41, ff. 5r–6r.

44 On Newton's research on Solomon's Temple, see David Castillejo, The expanding force in Newton's cosmos as shown in his unpublished papers (Ediciones de Arte y Bibliofilia, Madrid, 1981); Matt Goldish, Judaism in the theology of Sir Isaac Newton (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1998); and Tessa Morrison, Isaac Newton's Temple of Solomon and his reconstruction of sacred architecture (Birkhaüser, Basel, 2011).

45 On prytanea and other aspects of Newton's research into the original religion, see Westfall, ‘Newton's Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’, op. cit. (note 36); and Snobelen, ‘The true frame of Nature’, op. cit. (note 7).

46 First brought to attention in J. E. McGuire and P. M. Rattansi, ‘Newton and the “Pipes of Pan”’, Notes Rec. R. Soc.21, 108–143 (1966). But see also Volkmar Schüller, ‘Newton's Scholia from David Gregory's Estate on the Propositions IV through IX Book III of his Principia’, Between Leibniz, Newton, and Kant: philosophy and science in the eighteenth century (ed. Wolfgang Lefèvre), pp. 213–265 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2001).

47 Isaac Newton, A treatise of the system of the world (F. Fayram, London, 1728), pp. 1–4. For a discussion of the writing and publication of this work, see the Introduction in Isaac Newton, A treatise of the system of the world, 1731 edition, ‘Introduction’ by I. B. Cohen (Dawson's, London, 1969).

48 Newton, 1728, op. cit. (note 47), pp. 1–2.

49 Newton, ‘The original of religions’, Yahuda Ms. 41, f. 1r.

50 I am agreeing here with the claims made by Stephen Snobelen in his ‘The true frame of Nature’, op. cit. (note 7). He argues that Newton saw the need for a dual reformation of natural philosophy and religion, and that the correct reformation of both had to reveal the links and synergies between them. Moreover, he argues that this is a feature of Newton's outlook from very early in his career.

51 Schilt, ‘To improve upon hints of things’, op. cit. (note 9).

52 Schilt, ‘To Improve upon hints of things’, op. cit. (note 9), p. 76.

53 Newton to Oldenburg, 10 February 1671/2; Isaac Newton, Correspondence, op. cit. (note 25), vol. II, p. 109. Quoted from Schilt, ‘To improve upon hints of things’, op. cit. (note 9), p. 77. Isaac Newton, ‘A letter of Mr Isaac Newton … containing his new theory of light and colours’, Phil. Trans. R. Soc.80, 3075–3087 (19 February 1671/72); also available in Newton, Papers and letters on natural philosophy, op. cit. (note 25), pp. 47–59; and of course through the Newton Project.

54 Scott Mandelbrote, ‘“A duty of the greatest moment”: Isaac Newton and the writing of Biblical criticism’, Brit. J. Hist. Sci.26, 281–302 (1993).

55 Mandelbrote, ‘A duty of the greatest moment’, op. cit. (note 54), pp. 20, 13, 21. Newton, Yahuda Ms. 1.1, f. 3r.

56 Newton, Yahuda Ms. 1.1, f. 2r.

57 Newton, Yahuda Ms. 1.1, f. 1r.

58 Newton, Opticks, op. cit. (note 1), Huntington Library, Rare Books, Babson Newton 700873. See also Manuel, Isaac Newton, historian, op. cit. (note 7), pp. 112, 284. Manuel even includes a photograph of the annotated page: Plate 10, facing p. 117. I am very grateful to Dr Stephen Snobelen for bringing this annotation, and Manuel's discussion, to my attention.

59 Isaac Newton, Traité d'Optique, translated by Pierre Coste, pp. 582–583 (Pierre Humbert, Amsterdam, 1720). Unfortunately, we have no details about how this final passage came into Coste's hands, but it must have been sent to him by Newton. I am grateful to my colleague, Sergio Orozco-Echeverri, for bringing the French edition to my attention.

60 Matt Goldish sees ‘Of the Church’ as ‘the culmination’ of Newton's researches on religious history, and ‘possibly earmarked by the author for eventual publication’. See his ‘Newton's Of the Church’, op. cit. (note 36), p. 146.

61 Newton, ‘Theologiae gentilis origines philosophicae’, Yahuda Ms. 16.2, f. 1r.

62 Consider, for example, the title of Rob Iliffe's forthcoming book on Newton's religion, Priest of nature, op. cit. (note 7). See also Harold Fisch, ‘The scientist as priest: A note on Robert Boyle's natural theology’, Isis44, 252–265 (1953).

63 Newton, ‘The Original of religions’, Yahuda Ms. 41, f. 7r.

64 On the unity of Newton's thought, see Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs, The Janus faces of genius: the role of alchemy in Newton's thought (Cambridge University Press, 1991); James E. Force, ‘Newton's God of dominion: the unity of Newton's theological, scientific and political thought’, in Essays on the context, nature and influence of Isaac Newton's theology (ed. J. E. Force and R. H. Popkin), pp. 75–102 (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1990); and Stephen Snobelen, ‘To discourse of God’, op. cit. (note 7). For an opposing view, see Rob Iliffe, ‘Abstract considerations: disciplines, audiences and the incoherence of Newton's natural philosophy’, Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci.35, 427–454 (2004).