by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/18/20

Committee on Public Information

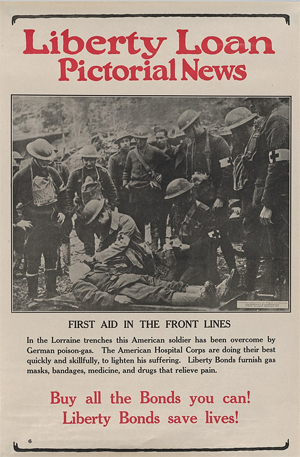

CPI pamphlet, 1917

Agency overview

Formed: April 13, 1917

Dissolved: August 21, 1919

Superseding agencies

liquidated to: Council of National Defense

similar later agencies: Office of War Information (WWII)

Jurisdiction: United States Government

Headquarters: Washington, D.C.

Employees: significant staff plus over 75,000 volunteers

Agency executives: George Creel, chairman; Robert Lansing, ex officio for State; Newton D. Baker, ex officio for War; Josephus Daniels, ex officio for Navy

Parent agency: Executive Office of the President

Child agencies: over twenty bureaus and divisions including: News Bureau; Film Bureau

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States created to influence public opinion to support US participation in World War I.

In just over 26 months, from April 14, 1917, to June 30, 1919, it used every medium available to create enthusiasm for the war effort and to enlist public support against the foreign and perceived domestic attempts to stop America's participation in the war. It used mainly propaganda to accomplish its goals.

Organizational history

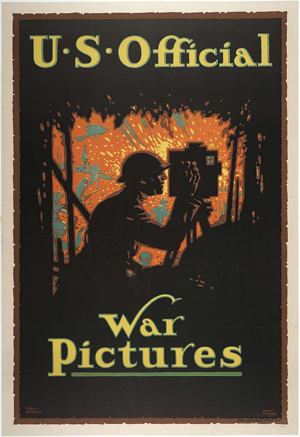

"U.S. Official War Pictures", CPI poster by Louis D. Fancher

Establishment

President Woodrow Wilson (the 28th president) established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) through Executive Order 2594 on April 13, 1917.[1] The committee consisted of George Creel (chairman) and as ex officio members the Secretaries of: State (Robert Lansing), War (Newton D. Baker), and the Navy (Josephus Daniels).[2] The CPI was the first state bureau covering propaganda in the history of the United States.[3]

Creel urged Wilson to create a government agency to coordinate "not propaganda as the Germans defined it, but propaganda in the true sense of the word, meaning the 'propagation of faith.'"[4] He was a journalist with years of experience on the Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News before accepting Wilson's appointment to the CPI. He had a contentious relationship with Secretary Lansing.[5]

Activities

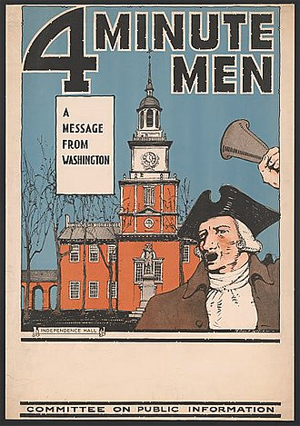

Wilson established the first modern propaganda office, the Committee on Public Information (CPI), headed by George Creel.[6][7] Creel set out to systematically reach every person in the United States multiple times with patriotic information about how the individual could contribute to the war effort. It also worked with the post office to censor seditious counter-propaganda. Creel set up divisions in his new agency to produce and distribute innumerable copies of pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men. CPI created colorful posters that appeared in every store window, catching the attention of the passersby for a few seconds.[8] Movie theaters were widely attended, and the CPI trained thousands of volunteer speakers to make patriotic appeals during the four-minute breaks needed to change reels. They also spoke at churches, lodges, fraternal organizations, labor unions, and even logging camps. Speeches were mostly in English, but ethnic groups were reached in their own languages. Creel boasted that in 18 months his 75,000 volunteers delivered over 7.5 million four minute orations to over 300 million listeners, in a nation of 103 million people. The speakers attended training sessions through local universities, and were given pamphlets and speaking tips on a wide variety of topics, such as buying Liberty Bonds, registering for the draft, rationing food, recruiting unskilled workers for munitions jobs, and supporting Red Cross programs.[9] Historians were assigned to write pamphlets and in-depth histories of the causes of the European war.[10][11]

4-Minute-Men 1917

The CPI used material that was based on fact, but spun it to present an upbeat picture of the American war effort. In his memoirs, Creel claimed that the CPI routinely denied false or undocumented atrocity reports, fighting the crude propaganda efforts of "patriotic organizations" like the National Security League and the American Defense Society that preferred "general thundering" and wanted the CPI to "preach a gospel of hate."[12]

The committee used newsprint, posters, radio, telegraph, and movies to broadcast its message. It recruited about 75,000 "Four Minute Men," volunteers who spoke about the war at social events for an ideal length of four minutes. They covered the draft, rationing, war bond drives, victory gardens and why America was fighting. They were advised to keep their message positive, always use their own words and avoid "hymns of hate."[13] For ten days in May 1917, the Four Minute Men were expected to promote "Universal Service by Selective Draft" in advance of national draft registration on June 5, 1917.[14]

The CPI staged events designed for many different ethnic groups, in their language. For instance, Irish-American tenor John McCormack sang at Mount Vernon before an audience representing Irish-American organizations.[15] The Committee also targeted the American worker and, endorsed by Samuel Gompers, filled factories and offices with posters designed to promote the critical role of American labor in the success of the war effort.[16]

The CPI's activities were so thorough that historians later stated, using the example of a typical midwestern American farm family, that[17]

Every item of war news they saw—in the country weekly, in magazines, or in the city daily picked up occasionally in the general store—was not merely officially approved information but precisely the same kind that millions of their fellow citizens were getting at the same moment. Every war story had been censored somewhere along the line— at the source, in transit, or in the newspaper offices in accordance with ‘voluntary’ rules established by the CPI.

Creel wrote about the Committee's rejection of the word propaganda, saying: "We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of facts."[18]

A report published in 1940 by the Council on Foreign Relations credits the Committee with creating "the most efficient engine of war propaganda which the world had ever seen", producing a "revolutionary change" in public attitude toward US participation in WWI:[19]

In November 1916, the slogan of Wilson's supporters, 'He Kept Us Out Of War,' played an important part in winning the election. At that time a large part of the country was apathetic.... Yet, within a very short period after America had joined the belligerents, the nation appeared to be enthusiastically and overwhelmingly convinced of the justice of the cause of the Allies, and unanimously determined to help them win. The revolutionary change is only partly explainable by a sudden explosion of latent anti-German sentiment detonated by the declaration of war. Far more significance is to be attributed to the work of the group of zealous amateur propagandists, organized under Mr. George Creel in the Committee on Public Information. With his associates he planned and carried out what was perhaps the most effective job of large-scale war propaganda which the world had ever witnessed.

Organizational structure

During its lifetime, the organization had over twenty bureaus and divisions, with commissioner's offices in nine foreign countries.[20]

Both a News Division and a Films Division were established to help get out the war message. The CPI's daily newspaper, called the Official Bulletin, began at eight pages and grew to 32. It was distributed to every newspaper, post office, government office, and military base.[21] Stories were designed to report positive news. For example, the CPI promoted an image of well-equipped US troops preparing to face the Germans that were belied by the conditions visiting Congressmen reported.[22] The CPI released three feature-length films: Pershing's Crusaders (May 1918), America's Answer (to the Hun) (August 1918), Under Four Flags (November 1918). They were unsophisticated attempts to impress the viewer with snippets of footage from the front, far less sensational than the "crudely fantastical" output of Hollywood in the same period.[23]

To reach those Americans who might not read newspapers, attend meetings or watch movies, Creel created the Division of Pictorial Publicity.[24] The Division produced 1438 designs for propaganda posters, cards buttons and cartoons in addition to 20000 lantern pictures (slides) to be used with the speeches.[25] Charles Dana Gibson was America's most popular illustrator – and an ardent supporter of the war. When Creel asked him to assemble a group of artists to help design posters for the government, Gibson was more than eager to help. Famous illustrators such as James Montgomery Flagg, Joseph Pennell, Louis D. Fancher, and N. C. Wyeth were brought together to produce some of World War I's most lasting images.

Media incidents

One early incident demonstrated the dangers of embroidering the truth. The CPI fed newspapers the story that ships escorting the First Division to Europe sank several German submarines, a story discredited when newsmen interviewed the ships' officers in England. Republican Senator Boies Penrose of Pennsylvania called for an investigation and The New York Times called the CPI "the Committee on Public Misinformation."[26] The incident turned the once compliant news publishing industry into skeptics.[27] There is some confusion as to whether or not the claims are correct based upon subsequent information published by the CPI.[28]

Early in 1918, the CPI made a premature announcement that "the first American built battle planes are today en route to the front in France," but newspapers learned that the accompanying pictures were fake, there was only one plane, and it was still being tested.[29] At other times, though the CPI could control in large measure what newspapers printed, its exaggerations were challenged and mocked in Congressional hearings.[30] The Committee's overall tone also changed with time, shifting from its original belief in the power of facts to mobilization based on hate, like the slogan "Stop the Hun!" on posters showing a US soldier taking hold of a German soldier in the act of terrorizing a mother and child, all in support of war bond sales.[31]

International efforts

The CPI extended its efforts overseas as well and found it had to tailor its work to its audience. In Latin America, its efforts were led where possible by American journalists with experience in the region, because, said one organizer, "it is essentially a newspaperman's job" with the principal aim of keeping the public "informed about war aims and activities." The Committee found the public bored with the battle pictures and stories of heroism supplied for years by the competing European powers. In Peru it found there was an audience for photos of shipyards and steel mills. In Chile it fielded requests for information about America's approach to public health, forest protection, and urban policing. In some countries it provided reading rooms and language education. Twenty Mexican journalists were taken on a tour of the United States.[32]

Political conflict

Creel used his overseas operations as a way to gain favor with congressmen who controlled the CPI's funding, sending friends of congressmen on brief assignments to Europe.[33] Some of his business arrangements drew congressional criticism as well, particularly his sale by competitive bidding of the sole right to distribute battlefield pictures.[34] Despite hearings to air grievances against the CPI, the investigating committee passed its appropriation unanimously.[35]

Creel also used the CPI's ties to the newspaper publishing industry to trace the source of negative stories about Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, a former newsman and a political ally. He tracked them to Louis Howe, assistant to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt and threatened to expose him to the President.[36] As a Wilson partisan, Creel showed little respect for his congressional critics, and Wilson enjoyed how Creel expressed sentiments the President could not express himself.[37][38]

Termination and disestablishment

Committee work was curtailed after July 1, 1918. Domestic activities stopped after the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. Foreign operations ended June 30, 1919. Wilson abolished the CPI by executive order 3154 on August 21, 1919.

The Committee on Public Information was formally disestablished by an act of Congress on June 30, 1919, although the organization's work had been formally completed months before.[39] On August 21, 1919, the disbanded organization's records were turned over to the Council of National Defense.[39]

Memoirs

Creel later published his memoirs of his service with the CPI, How We Advertised America, in which he wrote:[18]

In no degree was the Committee an agency of censorship, a machinery of concealment or repression. Its emphasis throughout was on the open and the positive. At no point did it seek or exercise authorities under those war laws that limited the freedom of speech and press. In all things, from first to last, without halt or change, it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world's greatest adventures in advertising.... We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts.

Criticism

Walter Lippmann, a Wilson adviser, journalist, and co-founder of The New Republic, was a sharp critic of Creel. He had once written an editorial criticizing Creel for violating civil liberties, as Police Commissioner of Denver. Without naming Creel, he wrote in a memo to Wilson that censorship should "never be entrusted to anyone who is not himself tolerant, nor to anyone who is unacquainted with the long record of folly which is the history of suppression." After the war, Lippmann criticized the CPI's work in Europe: "The general tone of it was one of unmitigated brag accompanied by unmitigated gullibility, giving shell-shocked Europe to understand that a rich bumpkin had come to town with his pockets bulging and no desire except to please."[40]

The Office of Censorship in World War II did not follow the CPI precedent. It used a system of voluntary co-operation with a code of conduct, and it did not disseminate government propaganda.[17]

Staff

Among those who participated in the CPI's work were:

• Edward Bernays, a pioneer in public relations and later theorist of the importance of propaganda to democratic governance.[41] He directed the CPI's Latin News Service. The CPI's poor reputation prevented Bernays from handling American publicity at the 1919 Peace Conference as he wanted.[42]

• Carl R. Byoir (1886 – 1957), like Bernays, a founding father of public relations in America.

• Maurice Lyons was the Secretary of the Committee. Lyons was a journalist who got involved in politics when he became secretary to William F. McCombs, who was Chairman of the Democratic National Committee during Woodrow Wilson's presidential campaign of 1912.

• Charles Edward Merriam, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago and an adviser to several US Presidents.

• Ernest Poole. Poole was the co Director of the Foreign Press Bureau division. Poole was awarded the very first Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his novel, His Family.

• Dennis J. Sullivan, Manager of Domestic Distribution for films made by the CPI.[43]

• Vira Boarman Whitehouse, director of the CPI's office in Switzerland. She repeatedly crossed into Germany to deliver propaganda materials. She later told of her experiences in A Year as a Government Agent (1920).[44]

See also

• American Alliance for Labor and Democracy

• Office of War Information

• United States Information Agency

• Writers' War Board

• World War I film propaganda

Notes

1. Gerhard Peters; University of California, Santa Barbara. "Executive Order 2594 - Creating Committee on Public Information". ucsb.edu.

2. United States Committee on Public Information; University of Michigan (1917). Official U. S. Bulletin, Volume 1. p. 4. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

3. Kazin, Michael (1995). The Populist Persuasion. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 69.

4. Creel, George (1947). Rebel at Large: Recollections of Fifty Crowded Years. NY: G.P. Putnam's Son's. p. 158. The quoted words refer to the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.

5. Creel, 158-60

6. George Creel, How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe.(1920)

7. Stephen Vaughn, Holding Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information (1980). online

8. Katherine H. Adams, Progressive Politics and the Training of America’s Persuaders (1999)

9. Lisa Mastrangelo, "World War I, public intellectuals, and the Four Minute Men: Convergent ideals of public speaking and civic participation." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 12#4 (2009): 607-633.

10. George T. Blakey, Historians on the Homefront: American Propagandists for the Great War (1970)

11. Committee on public information, Complete Report of the Committee on Public Information: 1917, 1918, 1919 (1920) online free

12. Creel, 195-6

13. Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I. New York: Basic Books, 2003; pg. 117.

14. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pp. 92-94.

15. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pp. 117-118.

16. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pg. 118.

17. Sweeney, Michael S. (2001). Secrets of Victory: The Office of Censorship and the American Press and Radio in World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-8078-2598-3.

18. George Creel, How We Advertised America. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920; pp. 4–5.

19. pp. 75-76, Harold J. Tobin and Percy W. Bidwell, Mobilizing Civilian America, New York: Council on Foreign Relations.

20. Jackall, Robert; Janice M Hirota (2003). Image Makers: Advertising, Public Relations, and the Ethos of Advocacy. University of Chicago Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-226-38917-2.

21. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pp. 118-119.

22. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pg. 173.

23. Thomas Doherty, Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II (NY: Columbia University Press, 1999), 89-91. Hollywood's films "served to discredit not only the portrayal of war on screen but the whole enterprise of cinematic propaganda." Hollywood titles included Escaping the Hun, To Hell with the Kaiser!, and The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin.

24. Library of Congress. "The Most Famous Poster". Retrieved 2007-01-02.

25. Creel, George. How we advertised America. New York & London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1920. p. 7.

26. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pp. 119-120.

27. Mary S. Mander, Pen and Sword: American War Correspondents, 1898-1975 (University of Illinois, 2010), 46. Creel believed his story was correct, but that opponents in the military who were jealous of his control of military information minimized what happened en route.

28. Creel, George (1920). How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information that Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe. Harper & Brothers.

29. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pg. 173. Creel blamed the Secretary of War for the false story.

30. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pg. 240.

31. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pg. 247.

32. James R. Mock, "The Creel Committee in Latin America," in Hispanic American Historical Review vol. 22 (1942), 262-79, esp. 266-7, 269-70, 272-4

33. Stone, Melville Elijah. Fifty Years a Journalist. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1921. p. 342-5.

34. Hearings Before the Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives, on the Proposed Revenue Act of 1918, Part II: Miscellaneous Taxes (Washington, DC: 1918), 967ff., available online, accessed January 19, 2011.

35. Stephens, Oren. Facts to a Candid World: America's Overseas Information Program. Stanford University Press, 1955. p. 33.

36. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory. p. 148-149.

37. Fleming, The Illusion of Victory. p. 315.

38. For Wilson's support of Creel to a group of senators, see Thomas C. Sorenson, "We Become Propagandists," in Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O'Donnell (eds.), Readings in Propaganda and Persuasion: New and Classic Essays (Sage Publications, 2006), p. 88. Asked if he thought all Congressmen were loyal, Creel answered: "I do not like slumming, so I won't explore into the hearts of Congress for you." Wilson later said: "Gentlemen, when I think of the manner in which Mr. Creel has been maligned and persecuted, I think it is a very human thing for him to have said."

39. Creel, How We Advertised America, pg. ix.

40. Ronald Steel, Walter Lippmann and the American Century.Boston: Little, Brown, 1980, pp. 125-126, 141-147; Fleming, The Illusion of Victory, pg. 335; John Luskin, Lippmann, Liberty, and the Press. University of Alabama Press, 1972, pg. 36

41. W. Lance Bennett, "Engineering Consent: The Persistence of a Problematic Communication Regime," in Peter F. Nardulli, ed., Domestic Perspectives on Contemporary Democracy (University of Illinois Press, 2008), 139

42. Martin J. Manning with Herbert Romerstein, Historical Dictionary of American Propaganda (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 24

43. "Dennis J. Sullivan collection: Veterans History Project (Library of Congress)". memory.loc.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-09.

44. Manning, 319-20

Further reading

• Benson, Krystina. "The Committee on Public Information: A transmedia war propaganda campaign." Cultural Science Journal 5.2 (2012): 62-86. online

• Benson, Krystina. "Archival Analysis of the Committee on Public Information: The Relationship Between Propaganda, Journalism and Popular Culture." International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society (2010) 6#4

• Blakey, George T. Historians on the Homefront: American Propagandists for the Great War Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1970. ISBN 0813112362 OCLC 132498

• Breen, William J. Uncle Sam at Home : Civilian Mobilization, Wartime Federalism, and the Council of National Defense, 1917-1919. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984. ISBN 0313241120 OCLC 9644952

• Brewer, Susan A. Why America Fights: Patriotism and War Propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq. (2009).

• Fasce, Ferdinando. "Advertising America, Constructing the Nation: Rituals of the Homefront during the Great War." European Contributions to American Studies 44 (2000): 161-174.

• Fischer, Nick, "The Committee on Public Information and the Birth of U.S. State Propaganda," Australasian Journal of American Studies 35 (July 2016), 51–78.

• Kotlowski, Dean J., "Selling America to the World: The Office of War Information's The Town (1945) and the American Scene Series," Australasian Journal of American Studies 35 (July 2016), 79–101.

• Mastrangelo, Lisa. "World War I, public intellectuals, and the Four Minute Men: Convergent ideals of public speaking and civic participation." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 12.4 (2009): 607-633.

• Mock, James R. and Cedric Larson, Words that Won the War: The Story of the Committee on Public Information, 1917-1919, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1939. OCLC 1135114

• Pinkleton, Bruce. "The campaign of the Committee on Public Information: Its contributions to the history and evolution of public relations." Journal of Public Relations Research 6.4 (1994): 229-240.

• Ponder, Stephen.. "Popular Propaganda: The Food Administration in World War I." Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly (1995) 72#3 pp. 539–50. it ran a separate propaganda campaign

• Schaffer, Ronald. America in the Great War: The Rise of the War-Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0195049039 OCLC 23145262

• Vaughn, Stephen. Holding Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information. (University of North Carolina Press, 1980). ISBN 0807813737 OCLC 4775452 online

• Vaughn, Stephen. "Arthur Bullard and the Creation of the Committee on Public Information," New Jersey History (1979) 97#1

• Vaughn, Stephen. "First Amendment Liberties and the Committee on Public Information." American Journal of Legal History 23.2 (1979): 95-119. online

• Merriam, Charles. American Publicity in Italy

• Smyth, Daniel. "Avoiding Bloodshed? US Journalists and Censorship in Wartime", War & Society, Volume 32, Issue 1, 2013. online

• Zeiger, Susan. "She didn't raise her boy to be a slacker: Motherhood, conscription, and the culture of the First World War." Feminist Studies 22.1 (1996): 7-39.

Primary sources

• Committee on public information, Complete Report of the Committee on Public Information: 1917, 1918, 1919 (1920) online free

• Creel, George. How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920.

• George Creel Sounds Call to Unselfish National Service to Newspaper Men Editor and Publisher, August 17, 1918.

• United States. Committee on Public Information. National service handbook (1917) online free

Archives

• "Records of the Committee on Public Information". 2016-08-15.

External links

• Guy Stanton Ford, "The Committee on Public Information," in The Historical Outlook, vol 11, 97-9, a brief history by a participant

• Committee on Public Information materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

• Open Library. Walter Lippmann; Public Opinion. 1922

• The Committee on Public Information

• Who's Who - George Creel

• WWI: The Home Front