by Paul Fuller

Myanmar Times

April 1, 2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

In 1880, Henry Olcott took it upon himself to restore true Sri Lankan Buddhism and "to counter the efforts of Christian missionaries on the island." In order to accomplish this aim, he adopted some of the methods of Protestant missionaries. An American scholar of religion Stephen Prothero stated that in Ceylon Olcott was performing "the part of the anti-Christian missionary." He wrote and distributed anti-Christian and pro-Buddhist tracts, "and secured support for his educational reforms from representatives of the island's three monastic sects." He used the Christian models for the Buddhist secondary schools and Sunday schools, "thus initiating what would become a long and successful campaign for Western-style Buddhist education in Ceylon."

-- Christianity and Theosophy, by Wikipedia

The modern Western understanding of Buddhism is sometimes in conflict with those forms of Buddhism practised in Asia. There is the expectation that all Buddhists -- monks and Iaypeople -- will regularly engage in meditation. For those who practise Buddhism in the West, meditation is an essential element. Buddhism will often be described as a spiritual path, more of a philosophy than a religion. This representation of Buddhism has become so entrenched in the modern Western imagination that it is not usually challenged.

Modern forms of Buddhism popularly practised in the West are not always concerned with important themes prominent in Asian Buddhism. Modern Buddhism lessens the focus on cosmology and the protective value of the Buddha and his teachings. Instead, it emphasises the rational and scientific aspects. The claim is often made that Buddhism is essentially scientific and rational, although the validity of this claim is far from clear. In a sense, our modern understanding of Buddhism is based on what Buddhists say they do, rather than on what they actually do.

The term used to describe this phenomenon is "Protestant Buddhism" because it resembles many of the key features of Protestant Christianity, following the bias of many original scholars of Buddhism. This romantic notion has influenced much of our understanding of Buddhism since the late 19th century.

The defining characteristic of Protestant Buddhism is the importance given to the laity and the subsequent lessening of the importance of the Sangha, the Buddhist monastics. The laity is given this enhanced importance, and this is arguably somewhat different from all previous forms of Buddhism. This movement is then lay in leadership.

Another feature of Protestant Buddhism is a suspicion of hierarchies. By this I mean that it focuses on a supposed egalitarian philosophy in Buddhism. Buddhism, in this understanding, has no religious elites in the Sangha who are closer to Nibbana than other members of Buddhist society. All are of an equal standing on the religious path. In Buddhist culture there is a structure in which the monastic is a field of merit and on the path to Nibbana, and the layperson aspires for a future rebirth in which the life of the monastic might be possible.

As I have said, Buddhism in this modern manifestation is all about meditation. Meditation is the essential practice of the modern Buddhist. However, traditionally lay Buddhists did not meditate. Those who wished to do so became monks, and even then relatively few monks devoted their lives to meditation. In Protestant Buddhism, as pioneers in its description like Richard Gombrich have explained, meditation is learned from a book, not from a teacher.

Protestant Buddhism tends toward a type of fundamentalism that is sometimes in conflict with traditional forms of Buddhism. It teaches that Nibbana is a goal that can be achieved in this life, rather than being a distant aspiration. The layperson can strive toward Nibbana and is not dependent on the monastic for either religious instruction or merit.

Also, Protestant Buddhism has the persistent mantra that the Buddha was an ordinary man who overcame all suffering. In conflict with this understanding is the traditional idea that a Buddha is not an ordinary human being. A Buddha lives for countless lives as an animal, a human or a god in order to generate enough merit to be born a person who can become a Buddha.

An interesting feature of Protestant Buddhism is its use of certain symbols that are relatively new in Buddhist history. Notable among these is the so-called Buddhist flag (sometimes called the sasana flag). This flag, well known throughout Buddhist Asia, was designed by a Sri Lankan JR de Silva, and an American, Henry S. Olcott, to mark the revival of Buddhism in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, in 1880. One could say it is an anti-colonial or even an American invention. It was accepted as the international Buddhist flag by the 1952 World Buddhist Congress. The flag itself is an uncomfortable creation, if I can use these terms, involving many historical, political and religious ideas.

The primary text of Protestant Buddhism is the Kalama-sutta with its supposed scientific and empirical advice to rely on "reason" and "logic" in the search for truth and salvation. The text is often described as containing the Buddha's advice on the superiority of reason and scientific enquiry. However, this is a highly selective reading of the text, which more correctly focuses on the nature of ethical and wholesome actions.

U Nu, the first prime minister of independent Burma, was a devout Buddhist, but his understanding of Buddhism shows many of the trademark themes of "Protestant Buddhism".

In interviews, U Nu described his understanding of his faith. He explained that many practices, such as making offerings, acquiring merit, and performing acts to counteract ill luck, are not important parts of what Buddhism is really about. For U Nu, the focus of Buddhism is meditation "which will deliver one from all suffering". U Nu stated that he became a "true Buddhist" only when he learned that "the truths of Buddhism can be tested" as in the selective reading of the Kalama-sutta. He stated that the Buddha said, "You must not believe anything that you cannot test yourself:

In this sense, Buddhism is not based on a set of true doctrines, but a set of theories comparable to scientific theories that can be empirically tested and accepted or rejected. One is a "genuine Buddhist" when one understands Buddhism in this way, and this is what attracted U Nu to Buddhism. Doctrines are tested in meditation. Further, meditation need not take place in a monastery but can be practised at home. One need not be a monk to meditate. However, in his private practice it is well known that U Nu practised more devotional forms of Buddhism.

U Nu also argued that anyone can become a Buddha -- a version of the "Buddha was an ordinary man" or "the scientific Buddha" idea explored most recently by the American scholar Donald Lopez. Buddhism is reduced to a set of key theories that are comparable to scientific ones, and the Buddha to an ordinary man, not a perfected ethical being.

In some ways, none of these tendencies that are prominent in Protestant Buddhism are surprising. However, one must stress that the rational, scientific, egalitarian version of Buddhism is a recent phenomenon emphasising themes either latent, or more likely unimportant, in traditional forms of Buddhism. At worst, they might be incredibly misleading and perplexing to those observing Buddhism as practised in Asia and lead us to ridicule elements in Asian Buddhism that are not scientific, rational and egalitarian.

In the current religious climate, such preconceived notions about the nature of Buddhism might lead observers to misunderstand the underlying reasons that explain why one can be involved in blasphemy against Buddhist sacred objects.

****************************

Protestant Buddhism

by Oxford Reference

Accessed: 8/11/20

Term introduced by the scholar Gananath Obeyesekere referring to a phenomenon in Sinhalese Buddhism having its roots in the latter half of the 19th century and caused by two sets of historical conditions: the activities of the Protestant missionaries and the close contact with the modern knowledge and technologies of the West. In 1815 the British become the first colonial power to win control over the whole of Sri Lanka and signed the Kandyan convention declaring the Buddhist religion practised by the locals to be inviolable. This article was attacked by Protestant evangelicals in England and the British government felt obliged to dissociate itself from Buddhism. The traditional bond between Buddhism and the government of the Sinhala people had effectively dissolved while official policy favoured the activities of Protestant missionaries and the conversion to Christianity had become almost essential for those who wished to join the ruling élite. Leader of the movement that started as a result of these conditions was Anagārika Dharmapāla. The movement can be seen both as a protest against the attacks on Buddhism by foreign missionaries and the adoption in the local Buddhism of features characteristic of Protestantism. In essence, Protestant Buddhism is a form of Buddhist revival which denies that only through the Sangha can one seek or find salvation. Religion, as a consequence, is internalized. The layman is supposed to permeate his life with his religion and strive to make Buddhism permeate his whole society. Through printing laymen had, for the first time, access to Buddhist texts and could teach themselves meditation. Accordingly, it was felt they could and should try to reach nirvāṇa. As a consequence lay Buddhists became critical both of the traditional norms and of the monastic role.

****************************

A Protestant Buddhism?

by Andrew Olendzki

Barre Center for Buddhist Studies

Spring 2011

‘Protestant Buddhism’ is a label that has been applied to certain progressive elements in the Theravāda tradition, first in Sri Lanka in the 19th century, and more recently to modernist Buddhism in this country and around the globe. It is sometimes used as a pejorative, to the extent the enterprise is regarded as tainted with orientalist and colonialist attitudes, along with the historical Euro-centrism that led the first western Buddhists to immediately begin the task of “improving upon” the traditional manifestations of Buddhism in Asia. Another point against it is its tendency to downplay or even marginalize the role of the ordained Sangha.

Yet there is also much to be said in favor of modernist trends in contemporary Buddhism, and I wonder if we might find a way of rehabilitating Protestant Buddhism to the satisfaction of its critics. A crucial first step in the process is to recognize that new forms of Buddhism, at their best, are based upon creative ways of synthesizing meaning rather than upon undermining the beliefs or practices of others. In other words, while it is not okay to say others have got it wrong and this is the right way of looking at things, it is entirely appropriate (even natural) to say “Here is an interesting new way of understanding things that I find particularly meaningful.”

Let’s look at some of the parallels. In ancient India the Brahmins held specialized sacred knowledge of the Vedic hymns, and were the only ones qualified to perform the rituals needed for the well being of the population. The entire Śramaņa movement was a rebellion against this privileged information, and the Buddha, like other wandering ascetics, taught that anyone can gain direct access to spiritual understanding by practicing meditation and understanding the Dhamma for themselves. This is much like the Protestants in Europe by-passing the Church and empowering people to study the Bible for themselves and forge their own meaning from it directly.

Over twenty-five centuries an orthodox Theravāda establishment grew and flourished in many Buddhist countries, built upon a preservation of the Pāli texts and their explication in commentaries such as those by Buddhaghosa. The monks (and nuns?) had direct access to the teachings through the study of Pāli and the practice of meditation, while the laity was cast in a supporting role of sustaining the monastics and practicing generosity and ethical behavior. In the twentieth century some Burmese teachers encouraged householders to practice meditation intensively on ten-day retreats, thus making the insights deriving from such practice directly available to them. This is one of the forms in which Theravāda Buddhism was imported to the West, where such regular meditation practice became popular among convert Buddhists.

Another development that gained momentum over the course of the twentieth century was the study of Buddhist texts and languages, including the complete translation of the Pāli canon. Good editions of these texts are now readily available to all in the English-speaking world, and even tools for learning Pāli are within easy reach. While we have not quite arrived at the point of finding a copy of the Dhammapada in one’s hotel room drawer, certainly almost every bookstore carries some selection of primary Buddhist texts, with many freely available on the internet. And people are reading them.

One of the more foundational insights of Buddhism, aligning it with the post-modern world view, is that a world of meaning is constructed anew each moment by each individual mind/body organism. The “world” is not “out there,” but is constructed in “this fathom-long body.” As information flows into the various sense doors, mediated by the structures of our sensory apparatus and the functions of our mental aggregates, views form about who we are and what sort of environment we inhabit. These views are often mistaken (distorted by delusion, clouded by defilements, and beset with ignorance) but we do the best we can each moment to gradually clarify and deepen our understanding. The process is aided by both hearing the Dhamma (or, nowadays, reading it) and investigating its meaning in personal meditative experience.

This being the case, having direct access to the teachings of the Buddha, and being encouraged and supported in the regular practice of meditation, can only be a good thing. Even if we get it wrong once in a while, better to be actively inquiring into the meaning of the Dhamma at every opportunity than to passively accept a tradition in a given form. How many times has the Buddha said “Listen carefully, and I will speak…,” and how many times do we find the phrase “Here are the roots of trees. Meditate!”

Care must be taken to avoid the pitfalls. We are not necessarily better at understanding these teachings than all the Buddhists before us just because we are moderns or westerners or humanists or typing on keyboards. We cannot assume that the troubling bits, about miracles, rebirth, and hell realms, for example, must not be “true” and that we, of course, know better. It is possible to hold the greatest respect for all those who think differently than ourselves, for all those who construct their own meaning of these teachings differently than we do, and simply say at some point that we are not capable of seeing it that way. There is a huge difference between thinking differently from another and considering the other to be mistaken.

So by all means let us keep reading the texts, very carefully, and see how creatively and meaningfully we can allow the teachings they contain to guide the way we live our lives and shape our world. Let’s also engage in the careful investigation of experience, moment by moment, and allow the insights so gained to inform and inspire our understanding. As part of this practice, let us be very watchful over our own attitudes to ensure that toxins such as pride, intolerance, or prejudice about other opinions do not spill out and reveal how much work has still to be done. And, let’s continue to honor and learn from the Elders.

****************************

Protestant Buddhism Explanation: What It Is; What It Isn't

by Barbara O'Brien

Learn Religions

Updated August 27, 2018

You may stumble into the term "Protestant Buddhism," especially on the Web. If you don't know what that means, don't feel left out. There are lots of people using the term today who don't know what it means, either.

In the context of a lot of current Buddhist criticism, "Protestant Buddhism" appears to refer to a tepid western approximation of Buddhism, practiced mostly by upper-income whites, and characterized by an emphasis on self-improvement and rigidly enforced niceness. But that's not what the term originally meant.

Origin of the Term

The original Protestant Buddhism grew out of a protest, and not in the West, but in Sri Lanka.

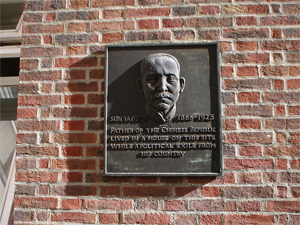

Sri Lanka, then called Ceylon, became a British territory in 1796. At first, Britain declared it would respect the people's dominant religion, Buddhism. But this declaration raised a furor among evangelical Christians in Britain, and the government quickly backtracked.

Instead, Britain's official policy became one of conversion, and Christian missionaries were encouraged to open schools all over Ceylon to give the children a Christian education. For Sinhalese Buddhists, conversion to Christianity became a prerequisite for business success.

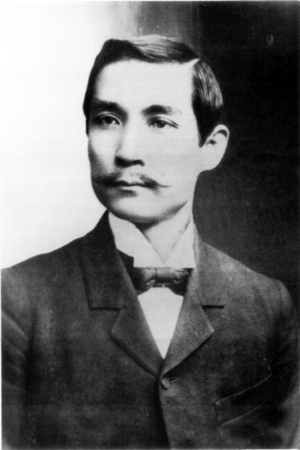

Late in the 19th century, Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933) became the leader of a Buddhist protest/revival movement. Dharmapala also was a modernist who promoted a vision of Buddhism as a religion compatible with science and western values, such as democracy. It is charged that Dharmapala's understanding of Buddhism bore traces of his Protestant Christian education in the missionary schools.

The scholar Gananath Obeyesekere, currently an emeritus professor of anthropology at Princeton University, is credited with coining the phrase "Protestant Buddhism." It describes this 19th-century movement, both as a protest and an approach to Buddhism that was influenced by Protestant Christianity.

The Protestant Influences

As we look at these so-called Protestant influences, it's important to remember that this applies mostly to the conservative Theravada tradition of Sri Lanka and not to Buddhism as a whole.

For example, one of these influences was a kind of spiritual egalitarianism. In Sri Lanka and many other Theravada countries, traditionally only monastics practiced the full Eightfold Path, including meditation; studied the sutras; and might possibly realize enlightenment. Laypeople were mostly just told to keep the Precepts and to make merit by giving alms to monks, and perhaps in a future life, they might be monastics themselves.

Mahayana Buddhism already had rejected the idea that only a select few could walk the path and realize enlightenment. For example, the Vimalakirti Sutra (ca. 1st century CE) centers on a layman whose enlightenment surpassed even the Buddha's disciples. A central theme of the Lotus Sutra (ca. 2nd century CE) is that all beings will realize enlightenment.

That said -- As explained by Obeyesekere and also by Richard Gombrich, currently president of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, the elements of Protestantism adopted by Dharmapala and his followers included the rejection of a clerical "link" between the individual and enlightenment and an emphasis on individual spiritual effort. If you are familiar with early Protestantism vis à vis Catholicism, you will see the resemblance.

However, this "reformation," so to speak, was not with Asian Buddhism as a whole but with Buddhist institutions in some parts of Asia as they existed a century ago. And it was led primarily by Asians.

One Protestant "influence" explained by Obeyesekere and Gombrich is that "religion is privatized and internalized: the truly significant is not what takes place at a public celebration or in ritual, but what happens inside one's own mind or soul." Notice that this is the same criticism leveled by the historical Buddha against the Brahmins of his day -- that direct insight was the key, not rituals.

Modern or Traditional and East Versus West

Today you can find the phrase "Buddhist Protestantism" being used to describe Buddhism in the West generally, particularly Buddhism practiced by converts. Often the term is juxtaposed with the "traditional" Buddhism of Asia. But the reality is not that simple.

First, Asian Buddhism is hardly monolithic. In many ways, including the roles and relationship of clergy and laypeople, there is a considerable difference from one school and nation to another.

Second, Buddhism in the West is hardly monolithic. Don't assume that the self-described Buddhists you met in a yoga class are representative of the whole.

Third, many cultural influences have impacted Buddhism as it has developed in the West. The first popular books about Buddhism was written by westerners were more infused with European Romanticism or American Transcendentalism than with traditional Protestantism, for example. It's also a mistake to make "Buddhist modernism" a synonym for western Buddhism. Many leading modernists have been Asians; some western practitioners are keen on being as "traditional" as possible.

A rich and complex cross-pollination has been going on for more than a century that has shaped Buddhism both East and West. Trying to shove all that into a concept of "Buddhist Protestantism" doesn't do it justice. The term needs to be retired.

****************************

Protestant Buddhism

by David Chapman

vividness.live

June 24, 2011

Many Western Buddhists would consider the following ideas obviously true, and perhaps as defining Buddhism:

1. Everyone can potentially attain enlightenment

2. Religious practice is your personal responsibility; no one can do it for you

3. You don’t necessarily have to have help from monks to practice Buddhism effectively

4. Non-monks can teach Buddhism; celibacy is not essential to religious leadership

5. Ordinary people can and should meditate; meditation is the main Buddhist practice

6. Careful observation of your own inner thoughts and feelings is the essence of meditation

7. Ordinary people can, and should, read and interpret Buddhist texts, which should be available in translation

8. Ritual is not necessary; it’s a late cultural accretion on the original, rational Buddhist teachings

9. Magic, used to accomplish practical goals, is not part of Buddhism

10. Buddhism doesn’t believe in gods or spirits or demons; or at any rate, they should be ignored as unimportant

11. Buddhism doesn’t believe in idols (statues inhabited by gods)

12. Buddhist institutions can be useful, but not necessary; they tend to become corrupt, and we should be suspicious of them

13. Everyday life is sacred

These ideas come mainly from Protestant Christianity, not traditional Buddhism. They are not entirely absent in traditional Buddhism. However, mostly, in traditional Buddhism:

1. Only monks can potentially attain enlightenment

2. Religious practice is mainly a public, ritual affair, led by monks; the lay role is passive attendance

3. There is no Buddhism without monks

4. Only monks can teach Buddhism, and celibacy is critical to being a monk

5. Only monks meditate, and very few of them; meditation is a marginal practice

6. Meditation is mainly on subjects other than one’s self

7. Only monks read Buddhist texts, their interpretation is fixed by tradition, and they are available only in ancient, dead languages

8. Essentially all Buddhist practice is public ritual

9. Much of Buddhist practice aims at practical, this-world goals, by magically influencing spirits

10. Gods and demons are the main subject of Buddhist ritual

11. Buddhists worship idols that are understood to be the dwelling-places of spirits

12. All reverence is due to the monastic, institutional Sangha, which is the sole holder of the Dharma

13. Everyday life is defiled, contaminating, and must be abandoned if you want to make spiritual progress

Buddhism is still understood and practiced this way in much of Asia.

So what?

I want to call some of the Protestant Buddhist ideas into question. Mostly, I think the “Protestant Reformation” of Buddhism has been a good thing. However, I find some aspects problematic.

My point is not that Protestant ideas should not be mixed with Buddhism, or that we should return to tradition. Rather, I will suggest that some of these ideas don’t work. Buddhists will need to find alternatives.

When Protestant ideas are misunderstood as essential to Buddhism, they cannot be challenged. Knowing they have only been added recently makes it possible to question them.

Most of the rest of this page discusses the history of the merging of Protestant ideas into Buddhism. Near the end, I begin to raise questions about whether it was good thing.

I’ll start by recounting a bit of the history of the Christian Protestant Reformation. Then I’ll look at Buddhism as it was in the mid-1800s, and the motivations for reform.

The Catholic Church before the Reformation

Before the Reformation, priests had a special, irreplaceable spiritual role. Only they could perform the public rituals that are the central religious practices: Mass, confession, extreme unction, and so forth. The Church functioned as intermediaries between lay (ordinary) people and God. Lay people had no direct access to the sacred.

Lay people attended rituals passively. The rituals were performed in Latin, which only priests knew. No one other than priests was authorized to teach the Gospel. The priesthood was (in theory) entirely and necessarily celibate.

The Bible was not available to ordinary people, and it was also written only in ancient dead languages. The interpretation of the Bible was fixed by institutional tradition; the ultimate source of religious authority was the Church itself.

“This world” (life on earth) was seen as defiled. The proper focus of religion was the “next world” (heaven or hell).

Despite that, religion provided this-wordly magical benefits to lay people. Particularly by praying to patron saints, one might receive practical benefits or protection. (There is a similarity between the role of Catholic saints and the many gods and spirits of Buddhism.)

The Church could also provide specific next-world benefits. It sold “indulgences,” which were widely understood as forgiving sins, and getting you out of purgatory, by transferring “merit” from the Church’s account to yours. (The theory of merit transfer is the main basis for lay donations to the Buddhist monastic Sangha. In Buddhism, too, its function is to improve your situation after death.)

The Protestant Reformation was a reaction to the wide-spread belief that the Church had become corrupt. It was immensely wealthy. It was seen as more concerned with pursuing money and power than proper religious matters. The selling of indulgences was seen particularly as abusive. The Church also licensed brothels, and instituted a tax specifically on priests who kept mistresses.

Moderate attempts at reform, from within the Church, failed.

The Protestant Christian Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a radical solution: it cut the Church out of the deal altogether. The central theoretical change was to give lay people direct access to God. That eliminated the special role of the Church.

According to Protestantism, each man can be his own priest. The Reformation rejected a separate priestly class, rejected monasticism, and closed monasteries where it could. (Similarly, Protestant Buddhism has extended the word “Sangha” to refer to lay believers as well as monks, and allows lay people to teach.) Protestantism rejected the theory of merit transfer.

According to Protestantism, lay people can access God in two ways: through scripture, and through prayer. It is the right, and the duty, of every layman to own a Bible written in his native language, and to read and understand it. The word of the Bible itself is the ultimate spiritual authority, not the Church’s interpretation of it.

Lay people also accomplish a direct, personal relationship with God, through private prayer. (This is analogous to the role of meditation in Protestant Buddhism. It supposedly gives you a direct connection with Ultimate Truth.) In silent contemplation, one should constantly examine one’s soul for impulses to sin. (This is analogous to the type of meditation in which one attends to ones’ own concrete thoughts and feelings, rather than contemplating often-abstract external matters—the more common practice in traditional Buddhism.)

Because you can have a direct relationship with God, you shouldn’t pray to saints. (Protestant Buddhism deemphasizes or eliminates celestial Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and so forth.)

Protestantism strips magical elements from the sacramental rituals (to varying degrees, according to sect). Ritual is often understood as providing a focus for community and an opportunity for personal experience, rather than being an irreplaceable sacred function.

Protestantism was iconoclastic, meaning that it encouraged the smashing of religious sculptures and paintings, because they were seen as false idols. It also opposed the wearing of priestly “vestments” (special clothes); this is mirrored in Protestant Buddhist contempt for Buddhist robes.

Some strains of Protestantism see everyday life as sacred. There should not be a special part of life set off for religious activity; the faithful should bring religious attention and intention to every part of the day. This is a major theme of Protestant Buddhism, too. It’s not usual in traditional lay Buddhist practice.

Protestant Buddhism

Here’s the Oxford Dictionary of Buddhism‘s take:

Protestant Buddhism… denies that only through the [monastic] Sangha can one seek or find salvation. Religion, as a consequence, is internalized. The layman is supposed to permeate his life with his religion and strive to make Buddhism permeate his whole society. Through printing laymen had, for the first time, access to Buddhist texts and could teach themselves meditation. Accordingly, it was felt they could and should try to reach nirvana. As a consequence lay Buddhists became critical both of the traditional norms and of the monastic role.

A classic definition is from Gombrich and Obeyesekere’s Buddhism Transformed:

The hallmark of Protestant Buddhism, then, is its view that the layman should permeate his life with his religion; that he should strive to make Buddhism permeate his whole society, and that he can and should try to reach nirvana. As a corollary, the lay Buddhist is critical of the traditional norms of the monastic role; he may not be positively anticlerical but his respect, if any, is for the particular monk, not for the yellow robe as such.

This kind of Buddhism is Protestant, then, in its devaluation of the role of the monk, and in its strong emphasis on the responsibility of each individual for her/ his ‘salvation’ or enlightenment, the arena for achieving which is not a monastery but the everyday world which, rather than being divided off from, should be infused with Buddhism.

Forces for Reformation

The Protestant-style reformation of Buddhism began in Asia, in the 1860s. Protestant missionaries were aggressively preaching Protestant ideas to Buddhists. Some Buddhists accepted key Protestant ideas, while rejecting Christianity overall, and used them to reform Buddhism.

The Buddhist Sangha, like the Catholic Church, was an immensely powerful, rich institution, which naturally opposed change. In both cases, Reformation was possible only due to an alliance among other classes, who were newly increasing in power. It was the same three groups in both cases:

• Reformation occurred when national rulers centralized state power and built effective bureaucracies. The Church/Sangha previously had secular power equal to, or surpassing, kings. Newly powerful rulers used the Reformation to break the power of the Church/Sangha, and to subordinate it to the state. Once they brought the Church/Sangha under control, they used it to impose a new, homogeneous national culture on the masses.

• The rise of a new, educated middle class was a key to Reformation. The middle class resented religious taxation, economic competition from the Church/Sangha, and its arbitrary, self-interested economic regulations. Intelligent, literate people also didn’t see why they should be excluded from direct religious practice; especially because much of the priesthood was neither intelligent nor literate nor had any interest in religion.

• Radicals within the Church/Sangha opposed its corruption, and wanted to return it to a purely religious function.

I’ll write more about this when I look at specific case histories (on Japan and Thailand).

The “Protestantization” of Buddhism has continued in the West in the past half-century. I’ll cover that as part of the recent history of “Consensus Buddhism.”

There are other important Protestant doctrines that have been partly imported into Buddhism. These include God and Christian ethics. I’ll write about God in Buddhism in my post on Japan, and about Christian influences on Buddhist ethics in a whole slew of posts later in this series. (Jeez, I’m issuing a lot of IOUs here!)

• I am skeptical about merit transfer, and I don’t believe lay people get their money’s worth when they pay for incomprehensible Buddhist rituals

• I don’t think monks have any intrinsic, exclusive powers; I don’t believe celibacy is dramatically valuable

• I do think lay people can benefit from personal practice, particularly meditation

• I think lay people can understand Buddhist scripture, and reading it can be spiritually helpful

• I don’t believe in magic or spirits (at least not in a straightforward, literal sense); and I think those beliefs can be counter-productive

• I am wary of religious institutions, which do often become corrupt

• I do think everything is sacred

Problems with Buddhist Protestantism

I also see some problems in the merger of Protestant ideas into Buddhism. I’ll write about those in my next several posts. A preview:

• Problems with scripture: who gets to decide what they mean?

• Problems with priests: “every man his own priest” doesn’t actually work

• Problems with meditation: what does it really do?

Further reading

There’s a large academic literature that discusses Protestant influences on Buddhism. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a single, comprehensive presentation. This post may be the first attempt to set out parallels between the Christian and Buddhist Protestant Reformations systematically.

This post was prompted by David L. McMahan’s The Making of Buddhist Modernism, in which Protestantism is a major theme.

The term “Protestant Buddhism” was introduced by Gananath Obeyesekere. His book with Richard Gombrich, Buddhism Transformed, has an extensive discussion. Unfortunately, the book considers only Sri Lanka, which is atypical in some ways. Also, they introduce some confusion by using “Protestant” to refer both to ideas imported from Protestant Christianity and to protest against colonialism.

If this post proves “controversial,” I would guess that it is more because of the parallels between traditional Buddhism and the pre-Reformation Catholic Church, than for the parallels between Protestant Christianity and contemporary Western Buddhism.

Protestant-style Buddhist reformers have found quotations from Buddhist scripture that suggest the Protestant ideas have always been Buddhist doctrine. It’s true that they are not entirely alien to Buddhism. However, in practice, they have almost always been marginal, almost everywhere. Buddhist scripture is vast, extremely diverse, and contradictory. You can find quotations in it to support almost anything, especially if you take short pieces out of context.

In any case, you can’t learn about traditional Buddhism, as practiced by lay people, from Buddhist texts. Scripture describes what ought to happen, rather than what does happen; and it is almost entirely about the Sangha, rather than lay people. And, the scriptures were written centuries ago, when things were often quite different.

To learn about traditional Buddhism, you either need to go to Asia and see for yourself, or read anthropology. If you have been to a Buddhist country, and observed lay practice (especially in rural areas where modern influences are least), you will probably recognize my description.

Otherwise, Melford Spiro’s Buddhism and Society is a classic study of Theravada Buddhist practice in Burma, and an excellent starting point. The Gombrich and Obeyesekere book is good for Sri Lanka. For Tibet, I recommend Geoffrey Samuel’s Civilized Shamans. All these books specifically address the nature of lay practice and the relationship between lay people and monks.

If anything in this post prompts incredulity, I will try to provide a citation to a reliable academic source.

Shock or horror I can’t help you with.