by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

In Two Volumes, Volume II

1899

-- The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett, 1851-1904

-- London Missionary Society, by Wikipedia

-- Chapter I: India in 1795, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter II: Nathaniel Forsyth and Robert May, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter III: Pioneer Work in South India: 1804-1820, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter IV: Pioneer Work in North India, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter V: South Indian Missions: 1820-1895, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

CHAPTER III: PIONEER WORK IN SOUTH INDIA: 1804-1820

From 1798 to 1803 the needs of India were before the minds of the Directors, and occupied a large share of their attention; but it was not until 1804 that they were able to send out the first company of missionaries. The conditions under which they were sent and the quality of the workers are quaintly set forth in the Report for 1804: —

'The Rev. Mr. Vos superintends the mission designed for Ceylon. His long standing in the Christian ministry, his faithful and successful labours therein, both at Holland and the Cape of Good Hope, added to the experience which he has acquired by his previous intercourse with the ignorant and uncivilized part of mankind, point him out as a person remarkably qualified to fill this station. He is accompanied by the Brethren Ehrhardt and Palm, natives of Germany, who received their education for missionary services at the seminary at Berlin, which was instituted chiefly, if not solely, for this object, and is under the care, as before mentioned, of that valuable instructor, the Rev. Mr. Jaenicke. They have also passed a considerable time in Holland, with a view of acquiring a more perfect acquaintance with the Dutch language, which is used in Ceylon. Mrs. Vos and Mrs. Palm have also an important service to occupy their zeal, in the instruction of the female natives, and in assisting in the education of children.

'Those who are designed to labour on the continent of India are the Rev. Messrs. Ringeltaube, Des Granges, and Cran. The first is a native of Prussia, who has already passed a short time in India, and has since held his principal intercourse with the Society of the United Brethren. The other missionaries have been about two years in the seminary at Gosport; and the whole have been ordained to the office of the Christian ministry, and recommended to the grace of God in the discharge of the arduous and important service to which they are called.

'It has been observed that some of our brethren are intended for the island of Ceylon, this being the station on which the attention of the Society, and of the Directors, is more especially fixed, and where, we trust, they will actually labour: yet, in the first instance, they are to accompany their brethren to Tranquebar, where they will obtain such accurate and comprehensive information as will greatly assist them in forming their future plans; and where they will find some Christian friends, who will promote their introduction, were not this rendered almost unnecessary by the kindness of one of his Majesty's principal secretaries of state, who has furnished them with a letter to his excellency Frederick North, the governor of the colony. The Directors have also fixed in their own minds a particular station for the labours of the brethren who are to remain on the Continent, and in which a very extensive field appears ripe for the harvest; this they have more particularly pointed out in their instructions, leaving, however, the ultimate decision to themselves, under the intimations of Divine providence, and the advice of those pious and well-informed friends with whom they will communicate on their arrival.'

No vessel of the East India Company was permitted to grant this company of missionaries a passage, as they went out in face of the open hostility of the Government, so the little band went to Copenhagen. Five of them sailed for India in a Danish vessel, bound for Tranquebar, on April 20, 1804, and were followed by Palm, who left Copenhagen on October 18. The five reached Tranquebar on December 5, and Palm arrived there June 4, 1805.

The Directors had further decided to establish a mission at Surat, and had appointed W. C. Loveless and John Taylor, M.D., to labour there. They sailed from London December 15, 1804, and reached Madras June 24, 1805. By this handful of workers the foundations were laid of the great work in Southern India which has been so successfully carried on throughout the century. From Tranquebar as a base these men, soon supplemented and strengthened by others, originated missionary work in the important fields of Ceylon, Travancore, Madras, Vizagapatam, Surat, and Bellary.

1. Ceylon. From 1805 to 1819 the work of the Society in Ceylon was carried on by four men. Unfortunately all the original records of this work also seem to have disappeared from the Society's archives, and all we know about it has to be gleaned from the somewhat scanty printed reports of the period. The four missionaries were M. C. Vos, J. P. Ehrhardt, J. D. Palm, and W. Read. The last had been for a short time at Tahiti, and was met by Mr. Vos at the Cape, and by him engaged for service in Ceylon. Vos settled in 1805 at Point de Galle, but was soon called to Colombo to take charge of a Dutch church there. Ehrhardt settled at Matura; Palm at Jaffnapatam, and Read at Point de Galle. Obstacles and difficulties similar to those which obtained in other parts of India were soon experienced. The missionaries were at first cordially welcomed by the governor, Mr. North, by whose influence the stations they occupied were assigned to them. The description of their work reads curiously in the light of to-day. 'The liberality of the government provides in part for the support of each of these missionaries, by which the funds of the Society will be relieved. They are actively engaged in acquiring the Cingalese language, in preaching to those who understand Dutch, and in instructing their children.' In Ceylon at this period there were large numbers of nominal Christians, but their condition may be gauged from one of Mr. Vos's letters: 'One hundred thousand of those who are called Christians, because they are baptized, need not go back to heathenism, for they never have been anything but worshippers of Buddha.'

Troubles soon arose. Mr. Vos's ministrations offended the Dutch consistory, and they demanded his expulsion from the island. He left in 1807, and soon after returned to the Cape of Good Hope. In 1812 Ehrhardt became minister of a Dutch church at Matura, and Palm of a Dutch church at Colombo. They both then ceased to depend upon the Society, and to be subject to its control. For two or three years they seem to have been active in educational work under government direction, and the last mention of Ceylon as a sphere of service occurs in the Report for 1817 and 1818. In the former we read: 'Mr. Ehrhardt and Mr. Read continue in Ceylon; the former has been removed by the government to Cultura, where he preaches alternately in Dutch and Cingalese. He has also established a school in which children are instructed in English, Dutch, and Cingalese, and on the Lord's day in the meaning of the chapter which they read. Mr. Read preaches twice a week in Dutch and keeps a day school.'

A few lines in the 1818 Report are the last reference in the Society's official records to this mission. After 1818 Ceylon disappears from the list of stations. That the men did good work is certain; but it is equally certain that as the agents were supported by Government, other considerations than missionary necessities became dominant. The mission became an early example of the unsatisfactory result, during the first twenty-five years of the Society's history, of attempting too soon to make missions locally self-supporting.

2. Travancore. The most remarkable man among the first group of South Indian missionaries was Ringeltaube. He was a Prussian, and was born in 1770. He studied at Halle, and while there was so powerfully impressed by the life of John Newton, that he was led, like Newton, to seek the Lord with all his heart, and to be ready for any sacrifice at the Lord's call. He was ordained in 1796, and in the same year accepted an offer to go to Calcutta as an agent of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. His stay there was brief, because 'he found he was to preach neither in Bengali nor in English, but in Portuguese to a mixed congregation of Portuguese, Malays, Jews, and Chinese.' In 1799 he returned to Europe. In 1803 he was accepted by the Society, and accompanied the others to Tranquebar1 [For much valuable information about Ringeltaube see an article by the Rev. W. Robinson in the Chronicle for January, 1889.]. There he took up with great energy the study of Tamil, and gradually was attracted towards Travancore as his field for service. One reason for this choice he gives in a letter to a friend, dated September 11, 1806: 'Long experience has taught me that in large towns, especially where many Europeans are, the Gospel makes but little progress. Superstition is there too powerfully established, and the example of the Europeans too baneful.' In February, 1806, Ringeltaube journeyed by way of Tuticorin to Palamcottah, and there obtained from the British Resident in Travancore a passport to enter that province. In April he visited Trevandrum, and finally obtained permission to establish a mission at Mayiladi, near Cape Comorin.

Travancore is remarkable for the beauty of its situation, for the character and customs of the people, and for the success which during the century has attended the work of the mission. Before describing the work of Ringeltaube, who can fairly claim the title of pioneer for Travancore — the scene of by far the greatest successes in the way of converts hitherto achieved by the Society in India— we will sketch the country and people in the words of Travancore's literary missionary, the Rev. Samuel Mateer2 [The Land of Charity, pp. 2, 3, et seq.].

'Travancore is a long, narrow strip of territory, measuring 174 miles in extreme length, and from 30 to 75 miles in breadth, lying between the Malabar Coast and the great chain of the Western Ghauts, a noble range of mountains, which, for hundreds of miles, runs almost parallel with the Western Coast of India, and which divides Travancore from the British provinces of Tinnevelly and Dindigul. It will be observed that Travancore thus occupies a very secluded position. The high mountain barrier on the East is almost impassable; the sea forms a protection on the West; it is therefore only from the North and the extreme South that the country is easily accessible.

'From its physical conformation Travancore is literally " a land of brooks of water, of fountains and depths, that spring out of valleys and hills." Fourteen principal rivers take their rise in the mountains, and before falling into the sea spread out, more or less, over the low grounds near the coast, forming inland lakes or estuaries of irregular forms, locally called "backwaters." These "backwaters" have been united by canals running parallel with the coast, and they are thus of immense value as a means of communication between the Northern and Southern districts. Travellers may in this way pass by water from Ponany, near Calicut, to Kolachel, a distance of not much under 200 miles. The mode of conveyance consists either of canoes hollowed out of the trunks of large trees, pushed along by two men with bamboo poles, or of "cabin boats," built somewhat like English boats, with a neat and comfortable cabin at the stern, which are propelled by from eight to fourteen rowers, according to their size. The principal road in Travancore also runs nearly parallel with the coast at a few miles' distance.

'The distinct castes and subdivisions found in various parts of Travancore are reckoned to be no less than eighty-two in number. All these vary in rank, in the nicely graduated scale, from the highest of the Brahmans to the lowest of the slaves. Occasional diversities, arising from local circumstances, are observable in the relative position of some of these castes. But speaking generally, all, from the Brahman priests down to the guilds of carpenters and goldsmiths, are regarded as of high or good caste; and from the Shanar tree-climbers and washermen down to the various classes of slaves, as of inferior or low caste.

'To give some definite idea of these component parts of the population, four principal castes may be selected as typical or illustrative of the whole. These are Brahmans, Sudras, Shanars, and Pulayars. The Brahmans in Travancore are divided into two principal classes — Namburis or Malayalim Brahmans, indigenous to the country, and foreign Brahmans, originally from the Canara, Mahratta, Tulu, and Tamil countries, but who are now settled in Travancore. The Namburi Brahmans, numbering about 10,000, are regarded as peculiarly sacred, and as exalted far beyond the foreign Brahmans. They claim to be the aboriginal proprietors of the soil, to whom the ancestors of the present rajahs and chiefs were indebted for all that they possessed. In consequence of their seclusion, caste prejudices, and strict attention to ceremonial purity, these Brahmans are almost inaccessible to the European missionary.

'The Brahmans in Travancore have secured for themselves a high and unfair superiority over all other classes. They are the only class that are free from all social and religious disabilities, and enjoy perfect liberty of action. The whole framework of Hinduism has been adapted to the comfort and exaltation of the Brahman. His word is law; his smile confers happiness and salvation; his power with heaven is unlimited; the very dust of his feet is purifying in its nature and efficacy. Each is an infallible pope in his own sphere. The Brahman is the exclusive and Pharisaic Jew of India.

'Even Europeans would be brought by Brahmans under the influence of these intolerable arrangements, did they only possess the power to compel the former to observe them. During the early intercourse of Europeans with Travancore, they were forbidden to use the main road, and required to pass by a path along the coast where Brahmans rarely travel; access to the capital was also refused as long as possible.

'The Sudras were originally the lowest of the four true castes, and are still a degraded caste in North India. But in the South there are so many divisions below the Sudras, and they are so numerous, active, and influential, that they are regarded as quite high-caste people. The Sudras are the middle classes of Travancore. The greater portion of the land is in their hands, and until recently they were also the principal owners of slaves. They are the dominant and ruling class. They form the magistracy and holders of most of the Government offices — the military and police — the wealthy farmers, the merchants, and skilled artisans of the country. The Royal Family are members of this caste. The ordinary appellation of the Sudras of Malabar is Nair (pronounced like the English word "nigher"), meaning lord, chief, or master; a marvellous change from their original position, according to Hindu tradition. By the primitive laws of caste they are forbidden to read the sacred books, or perform religious ceremonies, and are regarded as created for the service of the Brahmans.

'In consequence of their peculiar marriage customs the law of inheritance amongst the Sudras is equally strange. The children of a Sudra woman inherit the property and heritable honours, not of their father, but of their mother's brother. They are their uncle's nearest heirs, and he is their legal guardian. So it is, for example, in the succession to the throne.

'The Ilavars, Shanars, and others form a third great subdivision of the population. These constitute the highest division of the low castes. . . . The Ilavars and Shanars differ but little from one another in employments and character, and are, no doubt, identical in origin. The Shanars are found only in the southern districts of Travancore, between the Cape and Trevandrum; from which northwards the Ilavars occupy their place. These are the palm-tree cultivators, the toddy drawers, sugar manufacturers, and distillers of Travancore. Their social position somewhat corresponds to that of small farmers and agricultural labourers amongst ourselves....

'The Sudra custom of a man and woman living together as husband and wife, with liberty to separate after certain settlements and formalities, has been adopted by most of the Ilavars, and by a few of the Shanars in their vicinity; and amongst these castes also the inheritance usually descends to nephews by the female line. A few divide their property, half to the nephews and half to the sons. The rule is that all property which has been inherited shall fall to nephews, but wealth which has been accumulated by the testator himself may be equally divided between nephews and sons.

'These strange customs have sometimes occasioned considerable difficulty to missionaries in dealing with them, in the case of converts to Christianity. Persons who have been living together after the observance of the trivial form of "giving a cloth" are of course required to marry in Christian form. The necessary inquiries are therefore made into their history, and into the circumstances of each case of concubinage; deeds of separation, drawn up according to heathen law, are read and examined, and all outstanding claims are legally settled.

'The Shanars of South Travancore are of the same class as those of Tinnevelly, and in both provinces they have in large numbers embraced the profession of Christianity. Their employment is the cultivation of the Palmyra palm, which they climb daily in order to extract the sap from the flower-stem at the top. This is manufactured into a coarse dark sugar, which they sell or use for food and other purposes. The general circumstances of the Shanar and Ilavar population in Travancore, especially of the former, have long been most humiliating and degrading. Their social condition is by no means so deplorable as that of the slave castes, and has materially improved under the benign influence of Christianity, concurrently with the general advancement of the country.

'The slave castes — the lowest of the low — comprehend the Pallars, the Pariahs, and the Pnlayars. Of these the Pariahs, a Tamil caste, are found, like the Shanars, only in the southern districts and in Shencotta, east of the Ghauts; but they appear to be in many respects inferior to those of the eastern coast. Their habits generally are most filthy and disgusting. The Pulayars, the lowest of the slave castes, reside in miserable huts on mounds in the centre of the rice swamps, or on the raised embankments in their vicinity. They are engaged in agriculture as the servants of the Sudra and other landowners. Wages are usually paid to them in kind, and at the lowest possible rates. These poor people are steeped in the densest ignorance and stupidity. Drunkenness, lying, and evil passions prevail amongst them, except where of late years the Gospel has been the means of their reclamation from vice, and of their social elevation.'

The languages spoken in Travancore are Tamil and Malayalim. Tamil is spoken for about forty miles north of Cape Comorin; Malayalim north of the Neyattinkara River. That is, about one-fourth of the inhabitants of Travancore speak Tamil, and three-fourths Malayalim.

It was to this earthly Paradise, but rendered loathsome by the ignorance, cruelty, superstition, and pride of man, that the steps of Ringeltaube were providentially directed. His journal for 1806-7 describes how at Tuticorin the call to enter it came to him: —

'When in the evening, sitting in the verandah of the old fort (formerly the abode of power and luxury, now the refuge of a houseless traveller, and thousands of bats suspended from the ceiling), enjoying the extensive prospect, and communing with my own heart, and the God to whom mercies and forgivenesses belong, something frightened me by falling suddenly at my feet, and croaking, Paraubren Istotiram, i.e. God be praised; the usual words our Christians pronounce when greeting: I rejoiced to see an individual of that tribe among whom I had been so anxious to labour. Entered into conversation with him, as well as I could, to ascertain his ideas about religion, but was soon nonplussed by his stupidity. I could not force a word from him in answer to my plain questions, which he contented himself literally to give back to me. With a sigh, I was forced to dismiss him.'

This interview, unsatisfactory as it was, with a degraded and ignorant Shanar, strengthened the desire which already possessed Ringeltaube to reach Travancore. On April 25, 1806, his desire was gratified. Here is his own picture of the scene:—

'Set out at dawn, and made that passage through the hills, which is called the Arambuly gaut, about noon. Grand prospects of precipices, mountains, hills adorned with temples and other picturesque objects, presented themselves. My timid companions, however, trembled at every step, being now on ground altogether in the power of the Brahmans, the sworn enemy of the Christian name: and indeed a little occurrence soon convinced us that we were no more on British territory. I laid down to rest in a caravansary, appropriated for Brahmans only, when the magistrate immediately sent word for me to remove, otherwise their god would no more eat! I reluctantly obeyed, and proceeded round the southern hills to a village called Mayilady, from whence formerly two men came to Tranquebar to request me to come and see them, representing that two hundred heathens at this place were desirous to embrace our religion. I lodged two days at their house, where I preached and prayed; some of them knew the catechism. They begged hard for a native teacher, but declared they could not build a church, as all this country had been given by the king of Travancore to the Brahmans, in consequence of which, the magistrates would not give them permission. I spent here the Lord's day, for the first time, very uncomfortably, in an Indian hut, in the midst of a noisy gaping crowd, which filled the house. Perhaps my disappointment contributed to my unpleasant feelings; I had expected to find hundreds eager to listen to the Word, instead of which, I had a difficulty to make a few families attend for an hour.

'Travelling pleasantly under the shade of trees across hill and dale, with the ever-varying prospect of the gauts on my right, I reached Tiruvandirem, the capital of Travancore, on April 30. On the road I stopped, as travellers in general do, at Roman Catholic churches. Finding the dialect spoken here differing from the pure Tamil as much as the Yorkshire dialect does from pure English, I was much at a loss to understand them and make myself understood.'

Ringeltaube visited Anjengo, and on May 3 reached Quilon, and then by boat over the backwater travelled to Cochin. Here he met Colonel Macauly, the British Resident in Travancore, with whom he had been in correspondence, and who exerted his influence to get Ringeltaube permission from the rajah to build a church and reside in the country. Ringeltaube, on his return to Palamcottah, thus outlines his plan for the mission, and it is interesting to note that he here sketches the main lines which have been followed in the later development of the mission: —

'1. A small congregation to be begun near the confines of Travancore: £100 to be devoted to buying ground and erecting necessary buildings.

'2. A seminary of twelve youths, drawn from the existing congregations, to be formed: a pagoda and a half to be allowed for every youth per month, viz. 12s.

'3. When prepared, these youths to be sent out two and two, as itinerants, and two pagodas per month allowed as their stipend.

'4. If some of these prove very successful, and are truly gracious subjects, they should be ordained; but previous to this they should take a solemn oath not to exercise their ministry but in such a way as shall be approved by the Church.

'5. These to form an annual synod, under the presidency of an European missionary. Thus they will be gradually taught to govern a Church with prudence and wisdom, which catechists never learn at present.

'6. If any congregation wishes for a stationary preacher, one of these ministers to be given them, and they to stipulate to maintain him.

'7. A printing press to be united with this institution.

'8. Baptism to be administered wherever a true conviction of sin, and a belief in God our Saviour, appears; a promise to be exacted that such persons will be ready to suffer persecution for Christ, if necessary.

'9. A closer communion to be established among real converts, by means of a frequent enjoyment of the Lord's Supper, granted only to such.'

From 1806 to 1810 Ringeltaube carried on an active evangelistic work in Tinnevelly, with Palamcottah as his centre, paying also frequent visits to Travancore. Tinnevelly at this time contained about 5,000 Christians, under the care of native agents supported by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Ringeltaube worked much at first among these people. His method here and at Travancore was rapid itineration. In 1810 Oodiagherry became his centre of work, and in 1812 Mayiladi. In 1812 Ringeltaube's health began to fail. In 1816 he retired from the mission and went to Ceylon, and sailed thence intending to go to the Cape of Good Hope. Then he suddenly disappears, and is never more heard of. As a letter is extant, written from Colombo, stating that his liver was severely attacked, and as he is known to have sailed from Malacca, the most probable explanation is that he died and was buried at sea between Malacca and Batavia1 [See the Chronicle, 1889, p. 16.]. Of how or where his life closed no exact record appears to exist. He vanishes from the Society's story and work in a way which both arouses the desire to know more of him, and also fits in well with the unusual character of his previous career. The foundation of the Travancore Mission is inseparably linked with his name.

'This founder of our Travancore Mission was an able but eccentric man. He laboured devotedly, assiduously, and wisely for the conversion of the heathen and the edification of the Christian converts. Those whose motives appeared worldly and selfish were rejected by him, and all professing Christians were warned and instructed as to the spiritual character of the religion of Christ, and the permanent obligation of all relative and social duties. He was most generous and unselfish in regard to money, and is said to have distributed the whole of his quarter's salary almost as soon as it reached his hands. His labours were abundantly blessed, and his memory is precious and greatly honoured in connection with the foundation of this now flourishing native Christian Church1 [The Land of Charity, p. 265.].'

Prior to Ringeltaube's departure a successor. Mr. Charles Mead, had been appointed. He reached Madras, in company with Richard Knill, in August, 1816, but, owing to illness and to the death of his wife, did not arrive at Nagercoil until 1818. In September of the same year Knill rejoined Mead, having determined to find in Travancore his sphere of service. For two years the mission had been in sole charge of a catechist appointed by Ringeltaube, and he had done much good and useful work. There were when Ringeltaube departed about seven chief centres of work with chapels, five or six schools, and about 900 converts and candidates for baptism. This was no mean record for less than thirteen years of labour.

The Travancore British Resident in 1818 was Colonel Munro, an active friend of the missionary enterprise. Mead and Knill established their headquarters at Nagercoil, four miles from Mayiladi. Munro procured from the Ranee2 [The Queen Consort.] a bungalow for the missionaries, and a sum of 5,000 rupees, with which rice-fields were purchased, as an endowment for education. From this source, ever since 1819, the income of the English seminary has been derived. Munro, also probably in the effort to aid the funds of the mission, secured the appointment of Mr. Mead at Nagercoil as civil judge. Ten years earlier the Directors would have seen little or nothing anomalous in this. Now, although Mr. Mead held the appointment for a year, and discharged the duties so as to win the gratitude of the natives on the one hand, and to secure the external success of the mission on the other, the Board constrained him to resign the post.

'These early missionaries entered upon the work with great spirit and enterprise. A printing press was soon established. The seminary for the training of native youths was opened, and plans prayerfully laid and diligently carried out for the periodical visitation of the congregations and villages. The congregation at Nagercoil alone numbered now about 300, and a large chapel for occasional united meetings at the head station being urgently required, the foundation was laid by Mr. Knill on New Year's Day, 1819. Striking evidence of the strong faith and hope of these early labourers is seen in the noble dimensions of the chapel, the erection of which they then commenced. It is, perhaps, the largest church in South India, measuring inside 127 feet in length by 60 feet wide, and affording accommodation for nearly 2,000 persons, seated, according to Hindu custom, on the floor. Had this fine building not been erected, we should have in later years grievously felt the lack of accommodation for the great aggregate missionary and other special meetings of Christian people, which we are now privileged to hold within its walls1 [The Land of Charity, p. 269.].'

'During the two years after Mead and Knill's arrival, about 3,000 persons, chiefly of the Shanar caste, placed themselves under Christian instruction, casting away their images and emblems of idolatry, and each presenting a written promise declarative of his renunciation of idolatry and determination to serve the living and true God. Some of these doubtless returned to heathenism when they understood the spiritual character and comprehensive claims of the Christian religion, but most remained faithful and increasingly attached to their new faith. There were now about ten village stations, most of which had churches, congregations, and schools, all of them rapidly increasing. Native catechists were employed to preach and teach, and these teachers met the missionaries periodically for instruction and improvement in divine things.

'And now the tide of popular favour flowed in upon the missionaries. Not only did their message commend itself to the consciences of the hearers, but there was doubtless in many instances a mixture of low and inferior motives in embracing the profession of Christianity. The missionaries were the friends of the Resident, and connected with the great and just British nation. Hopes were perhaps indulged that they might be willing to render aid to their converts in times of distress and oppression, or advice in circumstances of difficulty. Moreover, the temporal blessings which Christianity everywhere of necessity confers, in the spread of education and enlightenment, liberty, civilization, and social improvement, were exemplified to all in the case of the converts already made. The kindness of the missionaries, too, attracted multitudes who were accustomed to little but contempt and violence from the higher classes, and who could not but feel that the Christian teachers were their best and real friends. What were these to do with those who thus flocked to the profession of Christianity? Receive them to baptism and membership with the Christian Church, or recognize them as true believers, they could not and did not; but gladly did they welcome them as hearers and learners of God's word. The missionaries rejoiced to think that the influence for good which they were permitted to exert, and the prestige attached to the British nation in India, were providentially given them to be used for the highest and holiest purposes. They did not hesitate, therefore, to receive to Christian instruction even those who came from mixed motives, unless they were evidently hypocrites or impostors. And from time to time, as these nominal Christians, or catechumens, appeared to come under the influence of the power of godliness, and as the instructions afforded them appeared to issue in their true conversion and renewed character, such were, after due examination and probation, received into full communion with the Christian Church. Their children, too, came under instruction at the same time in the mission schools, and became the Christian professors and teachers of the next generation1 [The Land of Charity, pp. 267-268.].'

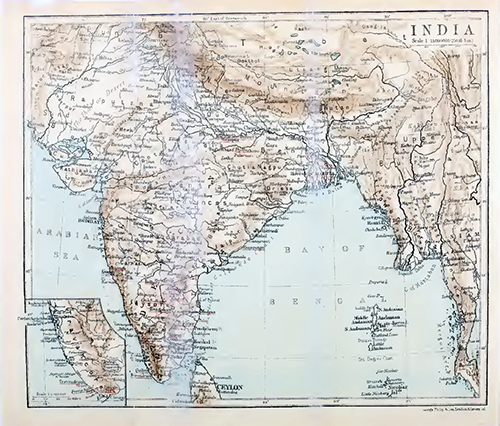

India

3. VIZAGAPATAM. This important city, with a population of about 30,000, the chief town of a district of the same name, is on the eastern coast of India, 400 miles north of Madras, in the district known as the 'Northern Circars.' Telugu is spoken, the tongue of from fifteen to twenty millions. Work here began in 1805. George Cran and Augustus Des Granges, the only members of the first company of workers for South India left in Madras after the commencement of the Ceylon and Travancore Missions, decided not to stay in Madras, but to take up work at Vizagapatam. The statement is made that Vizagapatam was chosen because of advice to that effect given by Carey to Mr. Hardcastle, with whom he kept up a regular correspondence1 [Life and Letters of Carey, Marshman, and Ward, vol. i. p. 395.]. There is also evidence that the first missionaries realized what very difficult mission-fields the large cities of India are, and that their call was to work among the natives. However this may be, Cran and Des Granges were welcomed by many of the European residents at Vizagapatam, and were invited to conduct English services in the Fort, for which they received a monthly salary from the governor. They also conducted services during the week for both Europeans and natives; and they opened a school for native children, the first three scholars being the sons of a Brahman. By November, 1806, a mission house had been completed, which cost, together with the site, 3,000 rupees. They then opened a 'Charity' School for Eurasian children, taking some of them as boarders. Towards this they received 1,300 rupees from residents and subscriptions for the support of the children. The two missionaries gave themselves with great diligence to the study of the language, and by constantly meeting and conversing with the natives, notwithstanding many disadvantages, made rapid progress in its attainment. They also began the task of translating the Bible into Telugu, and prepared two or three tracts. In these manifold and arduous labours they were greatly aided by a converted Brahman, Anandarayer by name, one of the most remarkable of the early Indian converts. The experience of this man is of exceptional interest, as he was the first Brahman converted in India by a member of the London Missionary Society. Cran and Des Granges sent home the following account of this remarkable and encouraging event: —

'A Mahratean, or Bandida Brahman, about thirty years of age, was an accountant in a regiment of Tippoo's troops; and, after his death, in a similar employment under an English officer. Having an earnest desire to obtain eternal happiness, he was advised by an elder Brahman to repeat a certain prayer four hundred thousand times! This severe task he undertook, and performed it in a pagoda, together with many fatiguing ceremonies, taking care to exceed the number prescribed. After six months, deriving no comfort at all from these laborious exercises, he resolved to return to his family at Nosom, and live as before. On his way home, he met with a Roman Catholic Christian, who conversed with him on religious subjects, and gave him two books on the Christian religion, in the Telinga1 [Now called Telugu.] language, to read. These he perused with much attention, admired their contents, and resolved to make further inquiries into the religion of Christ; and, if satisfied, to accept of it. He was then recommended to a Roman priest, who, not choosing to trust him too much, required him to go home to his relations, and to return again to his wife. He obeyed this direction; but found all his friends exceedingly surprised and alarmed by his intention of becoming a Christian, and thus bringing reproach upon his caste. To prevent this, they offered him a large sum of money, and the sole management of the family estate. These temptations, however, made no impression on him. He declared that he preferred the salvation of his soul to all worldly considerations; and even left his wife behind him, who was neither inclined nor permitted to accompany him. He returned to the priest, who still hesitating to receive him as a convert, he offered to deliver up his Brahman thread, and to cut off his hair — after which no Brahman can return to his caste. The priest perceiving his constancy, and satisfied with his sincerity, instructed, and afterwards baptized him: upon which, his heathen name, Subbarayer, was changed to his present Christian name, Anandarayer.

'A few months after this, the priest was called away to Goa; and having just received a letter from a Padree, at Pondicherry, to send him a Telinga Brahman, he advised Anandarayer to go thither; informing him, that there he would find a larger congregation, and more learned Padrees; by whom he would be further instructed, and his thirst for knowledge be much gratified. When he arrived at Pondicherry, he felt disappointed, in many respects; yet there he had the pleasure of meeting his wife, who had suffered much among her relations, and at last formed the resolution of joining him. He then proceeded to Tranquebar, having heard that there was another large congregation, ministers, schools, the Bible translated, with many other books, and no images in their churches, which he always much disliked, and had even disputed with the Roman priests on their impropriety. The worthy ministers at Tranquebar were at first suspicious of him; but, by repeated conversations with him, during several months that he resided among them, they were well satisfied with him, and admitted him to the Lord's Table. He was diligent in attending their religious exercises, and particularly in the study of the Bible, which he had never seen before. He began to make translations from the Tamil into the Telinga language, which he writes elegantly, as well as the Mahratta. His friends would readily have recommended him to some secular employment at Madras or Tanjore, but he declined their offers, being earnestly desirous of employment only in the service of the Church.

'Having heard of the missionaries at Vizagapatam, he expressed a strong desire to visit them, hoping that he might be useful among the Telinga nation, either in church or school. This his desire is likely to be gratified, the missionaries having every reason to be satisfied with his character; and, upon their representation, the Directors of the Missionary Society have authorized them to employ him, and to allow him a competent salary.

'A gentleman, who knew him well, says: "Whatever our Lord Jesus requires of His followers, he has readily performed. He has left wife, mother, brother, sister, his estate, and other advantages which were offered to him, and has taken upon himself all the reproaches of the Brahman caste; and has been beaten by some of the heathen, to whom he spake on Christianity; and still bears the marks of their violence on his forehead. He declined complaining of it, and bore it patiently."'

The assistance of so intelligent a convert as Anandarayer was a great help to the missionaries in translation work, and by January 20, 1809, Des Granges could write home, 'The Gospels of Matthew and Luke are complete in manuscript, and have gone through the first correction. The Gospels of Mark and John are begun. I have now four Brahmans engaged in this service. Anandarayer takes the lead; the others are all transcribers.' On April 15, 1809, an entry in Des Granges' journal runs: 'The translation of Matthew may now be pronounced complete; it has gone through many corrections. This evening delivered two copies, one for the Rev. D. Brown, of Calcutta, and one for the brethren at Serampore. Wrote also to them.' On May 16, 1810, he writes: 'The Gospel of Luke in the Telinga language was completed this day, and sent off to the Corresponding Committee of the British and Foreign Bible Society in Calcutta.' The four Gospels in Telugu were printed at Serampore, whither Anandarayer had gone to superintend their passing through the press, in 1811. Through the Auxiliary which had been formed in Calcutta, the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1810 granted a sum of £2,000 to be devoted to Indian Bible translation work during the years 1811, 1812, and 1813, half to go to the Serampore Mission, and half to the other agencies in India engaged in this work. Out of this grant the cost of printing the first edition of the Gospels in Telugu was met.

Neither of these pioneers in the Vizagapatam Mission was long spared to this field of labour. Cran died January 6, 1809, at Chicacole, whither he had gone in search of health. Des Granges died July 12, 1810. The Directors in 1805 and 1806 made strenuous efforts to reinforce the South Indian Missions. In January, 1807, John Gordon and William Lee had sailed for India via New York. There they were detained for a long time, and finally landed at Calcutta in September, 1809. Lee reached Vizagapatam in December, 1809, and Gordon in March, 1810. The deaths of Cran and Des Granges were a great loss to the mission, and very depressing to the new-comer. Both seem to have been men far above the average, both were devoted evangelists, and the latter had in him the making of a first-rate Biblical scholar. Lee and Gordon carried on the work jointly until the close of 1812, when Lee went to Ganjam to open up new work there. After about five years' labour, owing to ill-health, Mr. and Mrs. Lee returned to Madras, the mission at Ganjam was closed, and at the end of 1817 they returned to England and retired from service. Gordon at Vizagapatam had been encouraged by the arrival of a colleague, Mr. Edward Pritchett. He, in company with Mr. J. C. Brain, had been sent to Rangoon, in 1810, to found a mission in Burmah. But war had broken out there, and Mr. Brain died a few months after landing. Pritchett returned to Madras, and settled at Vizagapatam in November, 1811. Anandarayer had rendered Mr. Gordon most valuable services in translation work and in the mastery of Telugu, services similar to those which he had previously rendered to Des Granges. Gordon devoted himself to the completion of the New Testament. The services in the town were maintained, and a school for girls was established under the care of Mrs. Gordon and Mrs. Des Granges. Gordon and Pritchett also itinerated 'thrice a week' among the neighbouring villages. But sickness was frequent, and greatly hindered the work of the mission. In November, 1814, Mrs. Gordon died. She was described as 'truly pious, amiable, and useful.' In 1815 James Dawson joined the mission, and continued there in active service until his death in 1832. In 1818 the first complete Telugu New Testament was printed at Madras. The labour of revision and the completion of the version was the work of Mr. Pritchett. It was printed through the Calcutta Auxiliary of the Bible Society, who submitted the translation to experts in Madras, and upon their favourable report granted paper for 2,000 copies. These were printed in Madras under Mr. Pritchett's supervision during the latter half of 1818.

The conditions of mission-work during these early years are briefly put in a letter from Gordon and Pritchett written in 1813: 'We wish it were in our power to send you tidings of conversion among these heathen, but it is our lot to labour in a stubborn soil. But let none despair of success in the end, nor yet suppose that nothing has been done; for at least the minds of multitudes are dissatisfied in the vicinity of Vizagapatam; many have acknowledged themselves convinced of the evil and folly of their ways; and some that they are Christians at heart but afraid to confess it openly. Were it not for the unequalled timidity of this people, by which they are terrified at the thought of losing caste, and at its consequent inconveniences, we have no doubt we should have many converts. No converts can be gained, not even to a tolerable profession of Christianity, but such as have courage to forsake father and mother, and everything dear to them in this world, and fortitude and humility enough to live despised by all whose good opinion nature itself would lead them to value.'

4. Madras. No one of the original party of five who landed at Tranquebar in December, 1804, remained in the chief city of South-Eastern India. Dr. Taylor and W. Loveless had been sent out to found a mission at Surat. Dr. Taylor went on to Bengal, and on his return to Madras both were to go to Surat. Taylor never reached Surat, and Loveless by an unexpected series of events was led to settle in Madras.

In Madras, as early as 1726, a mission under the care of Schultze had been originated, chiefly by the aid afforded from the funds of the Christian Knowledge Society. But by the close of the eighteenth century the mission, under injudicious management, had fallen into disrepute. The English community was characterized by an almost utter neglect of both religion and morality. Hough, in his History of Christianity in India1 [Vol. iv. p. 136.], states: 'The Lord's Day was so disregarded that few persons ever thought of attending church. The only exceptions were Christmas and Easter, when it was customary for most persons to go to church. The natives looked upon these festivals as the gentlemen's pujahs, somewhat like their own idolatrous feasts. Every other Sabbath in the year was set apart as the great day of amusement and dissipation.' Dr. Kerr, a chaplain of great spirituality and earnestness, also wrote of this period: 'If ten sincere Christians would save the whole country from fire and brimstone, I do not know where they could be found in the Company's civil and military service in the Madras establishment.'

At this time there were great difficulties in Madras in the way of Christian work among the natives. Loveless was in India only on sufferance, the Government influence was entirely hostile to the evangelization of the natives, and Ringeltaube's opinion, that great cities were most unsatisfactory missionary fields of labour, applied then with special force to Madras. Hence Loveless was practically compelled to devote himself largely to the needs of European residents. He was, however, instrumental in founding two large schools, and in originating the Madras Bible and Tract Societies.

Early in his residence in Madras, and while Cran and Des Granges were still there, by the advice of Mr. Toriano, and through the influence of Dr. Kerr, the chaplain at Fort St. George, Loveless assumed the oversight of the Male Orphan Asylum. In this way he became self-supporting. "A few years later he purchased a piece of land in Black Town, and built Davidson Street Church, which was opened for worship in 1810. This building has ever since been a centre of spiritual life and inspiration. A writer in the Indian missionary paper Forward. for 1893, says:—

'If the old walls of Davidson Street could repeat what they have heard, what "notes of holier days" we now might hear. Hall and Nott, the first American missionaries to Bombay, held service here. Ringeltaube, in 1815, in a "very ordinary costume" — for he had no coat to his back, and wore a nondescript straw hat of country make — preached here his last sermon in India. After which he went on his mysterious mission to the eastward, and is supposed to have been murdered in Malayan jungles. John Hands, ill from overwork in Bellary, came to Madras to recruit himself by change of work. His fervid preaching attracted the multitude, and caused such a ferment in the place, that three young men went to the chapel one night with the avowed purpose of stoning him. The word, however, arrested them, and they departed ashamed, humbled and penitent; one of the three became a missionary in after years. Richard Knill helped on the good work begun by Mr. Loveless, but his service came to a sudden end by illness. It was always a great day when new arrivals from home came to the chapel. They had to preach as a matter of course, and in these occasional services occur the names of Henry Townley, Charles Mead, William Reeve, James Keith, and others whose record of noble service is "written in heaven."'

In 1816 Richard Knill reached Madras, but failure of health sent him to Travancore. A manuscript in Knill's handwriting exists, giving a history of these early Madras days. In it he says: 'For many years Loveless received no pecuniary aid from the Society. Providence so favoured him that he now liberally supports it. This is as it ought to be. This is what every real minister will do, if he can, but every missionary has not the opportunity. His boarding school, which is very respectable, and in which his excellent wife takes a very active and labouring part, affords him a sufficiency to support his own family, and to do good to others. It enables him also to give an affectionate and hearty welcome to the servants of Christ on their arrival in India, many of whom have found his house as the shadow of a great rock in a weary land. No missionary on his arrival in Madras should go to an inn for accommodation while Loveless is alive.'

A simple-minded, humble, devoted pastor, teacher and administrator, was the man who, contrary to his own anticipations, thus became a pioneer of the Madras Mission. Mr. Loveless, on the failure of his health in 1824, returned to England and shortly afterwards severed his connection with the Society. Under his care the mission, in which as preacher, evangelist to the natives, superintendent of education, and active agent in the preparation and spread of Christian literature, he had spent nearly twenty years, had been established upon a sound and serviceable basis.

5. Bellary. The foundations deep and lasting of the Bellary Mission were laid by a man whose name must ever stand very high upon the roll of South Indian missionary workers — the Rev. John Hands. He was born at Roade in Northamptonshire in 1780, studied at Gosport under Bogue, and sailed for India in 1809. He reached Madras in February, 1810. He had been destined for Seringapatam, but all efforts to get a footing there proved fruitless. Finally, with great difficulty, and only by the personal efforts of one of the chaplains, permission was obtained from the Government for Mr. Hands to settle at Bellary. This town, also the centre of a great district of the same name, lies north-west of Madras in the centre of the peninsula, about midway between Madras and Goa. Here the missionaries came into touch with people speaking a third great language — Canarese. Telugu and Tamil are also spoken in parts. Recognizing it as the missionary's prime duty to acquire as perfectly as possible the tongue of the people he comes to benefit, Hands gave his days and nights to the study of Canarese. There were no dictionaries or grammars, nor was any Anandarayer available. He therefore set about making for himself the necessary helps. In 1812 a grammar and vocabulary were commenced, and a version of the first three Gospels completed. In the same year a church, consisting of twenty-seven European and East Indian residents, was formed. A native school and also a 'charity' school for 'the education, and when necessary the support, of European and East Indian children were established.'

In 1812 Mr. J. Thompson, intended as the colleague of Mr. Hands, landed at Madras, but as he did not hold the permit of the East India Company — and this, it is needless to state, at that juncture would not have been given — he was ordered to leave the country. While preparing to obey he was seized with illness, and died. In 1813 Mr. Hands decided to make the instruction in the school more distinctly Christian. To this at first the native opposition was very strong, and many children were taken away. But he persevered, the children returned, and soon a second school was required. In 1815 he visited the annual festival held at Humpi, at which about 200,000 natives used to assemble. On this occasion the practice on the part of the missionary and his native helpers of preaching at the festival was begun, a practice which has been followed ever since. Long itinerating journeys for preaching and distributing tracts were undertaken. In 1815 a Tract Society was formed. In 1816 Mr. W. Reeve arrived as the colleague of Mr. Hands. In 1819 the first native convert was received into the Church.

6. SURAT. Although this spot figured in the first paper on desirable missions presented to the Society in 1795, it was 1815 before work was actually begun. Surat is in the Bombay Presidency, some distance north of Bombay itself. In 1804 Loveless and Taylor, who had been appointed to commence the mission, reached Madras; but the former, as we have seen, spent all his missionary life in that city, and the latter — the first medical missionary sent to India by the Society — wasted some years over real or fancied illness, and finally forsook the Society for a Government appointment. The mission was ultimately commenced by the Rev. J. Skinner and the Rev. W. Fyvie.

This sketch of pioneer work in South India may be not inappropriately closed by an extract from the Report of the Society for 1819: 'From the history of Protestant missions in India, particularly during the last few years, it is evident that a spirit of inquiry has pervaded no inconsiderable portion of its inhabitants; that the most obstinate and inveterate prejudices are dissolving; that the craft of the Brahminical system is beginning to be detected and its terrors despised, even by the Hindoos themselves; that the chains of caste, by which they have been so long bound, are gradually loosening; and that considerable numbers have absolutely renounced their cruel and degrading superstitions, and, at least externally, embraced the profession of Christianity. The renunciation of heathenism by numbers of the natives of Travancore, their professed reception of Christianity, the sanction and assistance given to the labours of Christian missionaries by the local authorities, and the translation of the Scriptures into the vernacular language of the country are circumstances which appear to justify the hope that the Almighty, in His designs of mercy towards India, is about to communicate the blessings of pure religion to the inhabitants of this most southern portion of the peninsula.

'To these highly important facts we add the countenance afforded to Christian missions by the British authorities. Not only are the labours of missionaries aided by many of the Company's chaplains, but even by many pious officers in the army, and also by numerous European residents who contribute liberally, and who aid the work by personal counsel and exertion. So great has been the change in India within a few years, that a judge lately returned from that country declares that "individuals who left it some years since, and brought home the prevalent notions of that day, can form no just estimate of the state of things now existing in India."'

This estimate must, of course, be understood as applying only to that section of the population which came under the influence of the missionaries, and which formed only a microscopical proportion of the people of the country.

[AUTHORITIES. — Letters and Official Reports; Transactions of the Society, vols, ii-iv.]