Chapter 3: An Ecumenical Vision for Global Mission [Taixu/Tai Hsu] [Bodhi Society] [Right Faith Buddhist Society of Hankou]

Excerpt from Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu's Reforms

by Don Alvin Pittman

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

CHAPTER 3: AN ECUMENICAL VISION FOR GLOBAL MISSION

During the last thirty years of his life, in addition to his efforts in the field of monastic education, Taixu devoted considerable energy to the establishment of regional and world Buddhist organizations. Xuming asserts that the reformer's growing interest in the 1920s in the global organization of Buddhists reflected a definite strategic decision on his part. At first, Taixu believed that the reorganization and reform of the monastic and lay communities within the Chinese Buddhist household would lead, rather naturally and directly, to the spiritual transformation of the nation and, eventually, of the entire world. However, given the failures and obstacles related to this internal Chinese reformation, Taixu began to think more expansively about organizing an ecumenical Buddhist movement on a global scale. Thus, while continuing efforts at institutional reform within the Chinese sangha, he hoped to find a way to bring together progressive-minded monks and laypeople from many nations who were prepared to commit themselves to a Buddhist mission to the world. It would be the conversion of the Christian West that would facilitate the thorough revitalization of Buddhism in East Asia and the shaping of a global Buddhist culture in which the enlightenment of every living being would be possible.1

Yet except for his brief visits to Taiwan and Japan in 1917, it was not until after 1923 that the Chinese master had any concrete opportunities to ...

[PAGES 106, 107 AND 108 MISSING]

national chapter of the World Buddhist Federation. Through these offices, permission was eventually obtained from the Ministry of the Interior for official Chinese delegates to be sent to the forthcoming Tokyo gathering of the world organization. Taixu continued to ponder how to organize effectively both monastic and lay Buddhists in a single national association with local chapters. 15

The East Asian Buddhist Conference convened in Tokyo, November 1-3, 1925, as planned the previous year.16 The Chinese delegation of twenty, led by Daojie and Taixu, included Chisong, Hongson, Wang Yiting, Hu Ruilin, and others.17 Buddhist representatives also attended from Korea and Taiwan. The only non-Asian Buddhist in attendance was the Mahayana scholar Bruno Petzold. Taixu began his major address with an assessment of global tensions and divisions. Asserting that only the compassionate spirit of Buddhism could save the modern world from continuing warfare and strife, he observed that some people simplistically associated these evils with capitalism and imperialism, which they sought to resist. However, he claimed, these calamities were more profoundly related to the blatantly materialistic desires that provided the foundation for all contemporary technological and consumer societies. Only Buddhism, with its teachings of no-self. the ten basic precepts, and perfect enlightenment, can constitute an effective antidote to the spiritual poison of modern materialism, Taixu concluded.

Commenting on the significance of Taixu's participation in the conference, the Japanese editors of the international journal The Eastern Buddhist later quoted the Chinese reformer as declaring:

The world today stands in urgent need for some means of salvation and I think only Buddhism can save the world, because various kinds of remedies have been tried and found wanting. Socialism has been proposed as a means to cure the evils of capitalism, and anarchism as an antidote to Imperialism. Thus far they have, however, failed to effect any cure of the social and international troubles from which the present world is suffering. In order to understand the reason for this failure, one must remember that these "isms" have been worked out by minds which have not been perfectly free from the three basic evils: Avarice, Hate, and Lust. These evils, if unchecked, will always manifest themselves in such crimes as robbery, murder, and adultery. Any remedy or means of cure for the present troubled world worked out by minds which are not yet perfectly free from such evils will tend only to increase the troubles instead of checking or preventing them.

To use the teachings of the ancient sages like Confucius or the precepts of the Prophets like Jesus Christ or Muhammad as a means of cure for the troubles of the present world is also inadequate, because the teachings of these ancient worthies have lost their hold on man's mind in the present materialistic world; for the religious beliefs of the Christians or Moslems have been shaken and the doctrines of these prophets about the Creator, the God, etc., have been disproved in the light of modern scientific discoveries, For the present skeptical world, only Buddhism with its teachings about the ten virtues as the starting point and Nirvana and "Perfect Enlightenment" as the ultimate object can be an effective remedy for the evils of the present world.18

Taixu grounded his appeal for ecumenical cooperation in East Asia in a frank evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of both Chinese and Japanese Buddhists. His principal argument was that each partner needed the other, and that what virtues Chinese Buddhists lacked might be prevalent among Japanese Buddhists, while certain virtues found wanting among Japanese Buddhists might be evident among the Chinese. Thus he declared that "as the Chinese and Japanese Buddhists now come in close touch with each other, they should learn each other's good points and work together for the propagation of the Buddhist religion." 19

With regard to the major weaknesses of Chinese Buddhist monks, Taixu charged that historically they had had lime interest in social service or educational ministries; that they had been so divided among different lineages and schools that they had failed to accomplish many important common goals; that they had generally been recluses without interest or involvement in community or national affairs; and that because they had not valued a modern, scientific education and an awareness of current events, they had not been able to contextualize their preaching to appeal to contemporary minds. Paradoxically, Taixu averred, the primary virtues of Chinese Buddhist monks represented the other side of the same coin. The community's most respected monks, he stated with appreciation, had always led lives of devotion and austerity, giving themselves to Study and contemplation. Although the community had divided into different traditions, Chinese Buddhists at their best had maintained a tolerant and liberal perspective. Like the Buddha, they had displayed a universal outlook, viewing all persons as members of the same family. Finally, they had retained the principal features of primitive Buddhism, despite transformations since the religion's introduction into China.

With regard to the good points and shortcomings of the Buddhist monks in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, Taixu asserted in a parallel fashion:

Of their good points there are four: (1) They organize themselves into bodies, which by cooperation are capable of doing charity work or carrying out large scale education campaigns for the benefit of the public; (2) Japanese monks are better trained for the work of propagating the Buddhist religion; (3) they are patriotic and often render useful, though worldly, services to the country and the community; and (4) their minds being more susceptible to Western thoughts and ideals, they are capable of making the Buddhist teachings acceptable to the modern mind. Regarding their shortcomings: (1) they are less devout in their religious life and unable to undergo the austerities of a religious recluse. as can their brethren in China and Tibet; (2) they are more sectarian and have no unity among the different sects; (3) they are too patriotic and nationalistic to pay much attention to the Buddha's teachings of universal brotherhood; and (4) they learn too much of modern scientific studies as to tinge the Buddhist teachings they preach with a touch of Modernism. 20

In conclusion, cognizant of heightening concerns throughout East Asia about Japanese expansionism -- and perhaps aware that some in his own delegation remained suspicious of their hosts' motives -- Taixu implored members of the Buddhist assembly not to permit nationalism to divide them or governments to co-opt their religious tradition and institutions for their own purposes.21 Indeed, he called for new measures of ecumenical cooperation to explore together appropriate means for preaching the Dharma and increasing popular devotion and morality. He advocated the establishment of an international Buddhist university and also encouraged the organization of compassionate social services for the general public. These included programs for famine and disaster relief work, aid to the aged and disadvantaged, promotion of new industries, and construction and maintenance of roads, bridges, and utilities. If all these new programs could be established, Taixu asserted, the Buddhists' critically important global mission might be advanced throughout the world. The immediate task of Asian Buddhists, he argued, was to modernize their own tradition, to bring the "Supreme Light" to the present world of darkness, and "to propagate the Buddhist religion among the Europeans and Americans whose civilization has been responsible for bringing about a world in which sensual desires and animal passions were reigning supreme."22

Taixu considered the trip to Japan a successful one for the Chinese delegation. [t also presented him with the opportunity to travel around the country for several weeks after the conference to meet with prominent Japanese scholars such as Nanjio Bunyiu, Takakusu Junjire, and D. T. Suzuki. The editors of The Eastern Buddhist subsequently remarked, "The visit of Chinese Buddhists in such a number and under such a management never took place in the history of both countries, Japan and China, and this was surely a great event to be recorded in big red letters in the annals of Eastern Buddhism."23 Taixu's leadership even prompted Mizuno Baigye, who had worked closely with the Japanese Foreign Ministry in arranging the conference, to proclaim:

For Taixu the Buddhists of Japan are new colleagues and good partners for future efforts to spread East Asian culture throughout the world. Let us hope that Buddhists of both countries will take Taixu as their central paradigm and mutually hold on to their strong points and rectify their shortcomings in order that we might look forward to the propagation of Buddhism in all the world."

Declaring a third international Buddhist conference "a desideratum for world peace for humanity," a standing committee for future international conferences was appointed. Selected to represent China were Ma Jinxun, director-general of the China Buddhist Federation, Beijing, and Hu Ruilin, former governor of Fujian and the new director of the Chinese Buddhist Federation, Beijing. Appointed for Japan were Kubokawa Kyokiyo, director-general of the Japan Buddhist Federation, Tokyo, and Mizuno Baigye, president of the Shina Jiho (China Times). A small committee for cooperation in promoting Buddhist social welfare work was also appointed, consisting of Wang Yiting, manager of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, Shanghai, and Watanabe Kaikyoku, member of the Board of Directors of the journal The Young East.25

Then thirty-five years old, Taixu was pleased with the accomplishments that these events represented in relation to his goal of increased international Buddhist cooperation. At the same time, according to Xuming, he was well aware that his enthusiasm for Buddhist ecumenism was not shared by all and that a new strategy was needed for promoting his Buddhist reform movement. Accordingly, after 1925, while continuing to promote Buddhist ecumenism in preparation for a more unified global mission, the Chinese master thought it increasingly important to address directly intellectual and religious leaden in the West. Xuming states that this new approach was reflected in the reformer's assertion that "if we want to constitute a new society based on right faith in the Buddhist Dharma, we should spread Buddhism as an international culture. And the preliminary step we have to take is to change the thinking of western intellectuals."26 What seemed a rather distant possibility for a Chinese Buddhist master who spoke no European languages became distinctly more real when, after the 1925 Tokyo conference, Dr. W H. von Solf, a German scholar serving at the time as ambassador to Japan, invited Taixu to visit Germany -- an invitation that, within a few years, the reformer was actually able to accept.

As significant as these mid-1920s international conferences were for Taixu's dream of an ecumenical Buddhist reform movement and a reenergized global mission, Welch's caution against an overly generous evaluation of the actual accomplishments of the World Buddhist Federation is well taken. As a viable organization, both the national and world federations functioned for only two years. A subsequent international conference, initially planned for Beijing, was never convened. Welch observes that, from the very beginning, the Federation was always greater on paper than in reality:

Elected to the council of the World Buddhist Federation in 1924 was Reginald Johnston, who had once published a book: about Chinese Buddhism, but was hardly a Buddhist himself. In fact, he had refused to attend the conference in 1923, as had Liang Qichao, who was also listed as a council member -- an honor of which he was perhaps unaware at the time. It seems almost certain that three other council members (Dixian,Yinguang, and Ouyang Jingwu) had not authorized the use of their names, since they were not on good terms with Taixu.

In brief, the World Buddhist Federation fell somewhat short of representing either Buddhism or the world. It was essentially a meeting between the Japanese and Taixu. Yet it was a significant step ahead in his career, for it showed that he had learned how to create organizations on paper and how to think: on a global scale.27

THE "PORTABILITY" OF CHINESE BUDDHISM

In the years immediately following the 1925 Tokyo conference, Taixu became increasingly discouraged by the ongoing bloody civil war in China. In fact, the warfare temporarily forced both his Wuchang Buddhist Institute and the Right Faith Buddhist Society of Hankou to cease functioning in October 1926, when the Nationalist army took Wuhan.28 Taixu was further disheartened by the aggressive, insensitive pursuit of economic and political interests in China both by Japan and by western nations. In reaction to foreign domination of Chinese interests, rising winds of Chinese nationalism swept the country in the mid-1920s. Growing popular resentment toward all forms of imperialism contributed to nationwide protests and occasional strikes, as in the May Thirtieth Incident of 1925, complicating cooperative ventures with the Japanese.29

Taixu was troubled, of course, by the failure of the World Buddhist Federation to maintain its promising ecumenical work. He was disappointed as well by the poor response to his efforts with the World Buddhist New Youth Society and its proposed World Propaganda Team (Shijie xuanchuan dui), neither of which was successful.30 His cooperative work with Zhang Taiyan, Wang Yiting, and others to establish an All-Asia Buddhist Education Association (Quanya fohua jiaoyu she), later renamed with the less ambitious title of the Chinese Buddhist Education Association (Zhonghua fohua jiaoyu she), also came to nothing.3I These ecumenical failures contributed to Taixu' s conviction that he needed to direct some of his energies toward finding ways to engage western intellectuals directly in considering the religio-philosophical heritage of Mahayana Buddhism.

As noted earlier, to Taixu the West represented a form of human civilization that was simultaneously fascinating and open to severe criticism. He wanted very much to visit Europe and the United States, not only to experience firsthand the vitality and ethos of western technological societies, but also, through his presentations in the West, to counter preconceptions about Chinese Buddhism that were prevalent there. Prejudicial views of the religion, he argued, were the result of Christian triumphalism, oversimplifications, and simple misunderstandings. Their attitudinal and relational consequences were quite hurtful to Chinese Buddhists and harmful to chances for world peace. Indeed, Reichelt once observed that, when discussing such misconceptions, "the voice and burning eyes of Taixu were witness to a very real pain and grief."32 Therefore, an important aim for the reformer became spreading the news throughout Europe and the United States about Chinese Buddhism's modern revival -- and about the possibility of a new global Buddhist movement that could ultimately transform not only East Asia but the entire world.

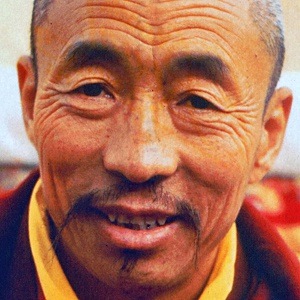

In a remarkable 1927 interview with Clarence H. Hamilton, Taixu shared his dream of a modern Buddhist mission to the West. During the discussion, the monk asked Hamilton to state his own perspective on an issue that Lewis Lancaster has in recent years referred to as the " portability" of Chinese Buddhism.33 Taixu had been contemplating the difficulties of cross-cultural mission and how to distinguish Chinese Buddhism's cultural "Chineseness" from its Buddhist essence. After describing Taixu's appearance -- his full mustache and horn-rimmed spectacles, round cheeks and boyish countenance, medium height, robust build, and "dark, thoughtful eyes" -- Hamilton recounts a quite interesting dialogue:

"Do you think," he [Taixu] said, "that Buddhism will penetrate and spread in the West?"

The question came as a surprise. I did not know that Taixu included the West in his purposes, though I had long known of the universal claims of Buddhism itself. But after all, it was natural, considering that he is an ardent propagandist as well as reformer. I essayed an answer.

"If the truth that is in Buddhism," I said, "can be put in a form that the Western mind can understand it has a chance of spreading, as does all truth eventually." Then I thought of the images and elaborate ceremonies I had witnessed in the temples and added: "But I do not believe that the forms and rites of the religion as these have been developed in the Orient can ever be taken over by the West any more than it is likely that purely Western forms of Christianity will survive in the East."

"Forms and ceremonies," the monk replied, "are but incidental. It is the truth that matters." ...

Then he told us that at the present time in Beijing National University where he had given a series of lectures there are seven or eight young men who are carefully studying Western knowledge and languages with the dominant purpose of fitting themselves to lecture on Buddhism before the people of the West. When' said in reply that Buddhism as a philosophy is already studied in Western university centers, that even as a religion it has some temples in California, and that Japanese monks have already been known to lecture there he replied eagerly, "Yes, that is well known to me. But Buddhism in California is for the Asian peoples residing there. Our purpose is not to spread the doctrine of the Buddha before those who already know it, but to carry it far and wide among the people of the West who yet are ignorant, particularly of the Northern Buddhism such as we have in China and Japan."

"But you say," he went on, his thought still busy with his first question, "that the truth of Buddhism must be made comfortable to the Western mind. Let me ask if you think that the Western mind is by nature favorable or unfavorable to Buddhist truth." ...

"I do not think," I said to Taixu, "that the dominant values cherished by the Western mind are very favorable to Buddhism as I understand it. The West values striving, achievement, reformation in the concrete outer world of nature and human affairs. But Buddhism seems to me to exalt contemplation, meditation, the quest for inward peace and poise -- a type of achievement indeed, hut one which is subjective and mystic, which tends to still the restlessness of endeavor in the external world. That Buddhism could appeal to a majority in the West is most doubtful. There are those, however, in the West who find its dominant tendencies too much for them. Such find the thought of ceaseless striving a burden and long for peace and rest. Such are likely to have the mystic taste most sensitive to the values of Buddhism."

A graver look deepened on the thoughtful countenance of the monk when my words were interpreted to him, as though some oft-recurring but not very happy reflection were stirred. "But has not Western striving," he said, "resulted in a European War? It would seem to me that after such an experience a larger proportion of the Western people must feel the need for something like Buddhism. Surely after such a catastrophe they will the more willingly listen to us. Mere striving cannot be the final word." 14

While Taixu considered these matters and contemplated how to present the Dharma to western intellectuals, he was able to arrange a meeting with Chiang Kai-shek in Nanjing on June 23, 1928, seeking his support for a national organization of Buddhist monks and laymen. Chiang had just returned from a confrontation with Japanese forces at Ji'nan in Shandong province as the Northern Expedition advanced on Beijing against the last remaining warlord, Zhang Zuolin (1873-1928). By the time of their meeting, the Nationalist forces had captured Beijing, and Zhang had been killed trying to escape. Chiang believed that he was finally in a position to consolidate his power, unite China, and progressively establish his country as a world power. The general, who would soon marry Soong Meiling in a Christian ceremony, and who became a Christian convert himself in 1930, listened attentively to Taixu's assertions that a modernized, reformed Buddhism had a major role to play in China and the world. The Mahayana Buddhist master stated:

Buddhism is an expression of the highest ideals of the people of the world. In particular its devotion to saving the world has no equal among other forms of learning or religion. [Yet] it must adapt to the ideas of our time and to the contemporary life of our country. Then and only then can the religion be promoted without any obstacles. This time of beginning political tutelage is a time of reform. The best idea is to establish a single Buddhist organization able to unify both monastic and lay followers so that it may benefit the citizens' prosperity, the country's strength, the government's orderly rule. and common goodness.35

Chiang commended Taixu for his remarks and introduced him to other government officials, who at that point were not at all encouraging about a specifically "religious" association (zongjiao hui). According to Yinshun, they suggested instead a more "timely" consideration of a Buddhist "study" organization (foxue hui). As a result, on July 28. 1928. Taixu established the Chinese Buddhist Study Association (Zhongguo foxue hoi), hoping that it might develop into a truly representative national body. Although this did not happen,16 soon after his meeting with Chiang Kai-shek and other Guomindang officials, Taixu was able to use these contacts, as well as his ambassadorial invitation co visit Germany, to obtain official support for a major tour of Europe, the United States, and Japan. He departed in August 1928 and did not return until late April 1929.

A MISSION TO THE WEST

As Dongchu points out, the tour did give the reformer an opportunity to tell interested westerners about the Buddhist revival in China and to discuss his proposal for a World Buddhist University (Shijie fohua daxue). later renamed the World Buddhist Institute (Shijie foxue yuan), an idea that Taixu had first put forth in 1925. Similar proposals had been made by others about the same time, including Bruno Petzold, who at the 1925 East Asian Buddhist Conference in Tokyo had also urged the creation of an "Institute of Mahayana Buddhism" designed "to investigate Mahayana Buddhism and explain it to the Western world."37 Similarly, the German diplomat-scholar W H. von Solf, acknowledging the need for westerners to learn more about eastern Buddhism and its potential contribution to human community, proposed "a comprehensive Mahayana institute in Tokyo or Kyoto."38 The structure of Taixu's proposed educational institution was first outlined as shown in Table 2. Xuming notes that the idea was later refined, and the hoped-for institute restructured, as indicated in Table 3.

The editors of LiJixu dashi huanyou ji (A Record of the Venerable Master Taixu's World Travel) have documented how Taixu was warmly greeted as an important dignitary by diplomats of the Chinese legations in Europe and the United States. He was photographed with government and civic leaders and provided with funds for donations to host organizations. On September 15, 1928, he was first welcomed to Paris, where he was to spend more than thirty days. On September 27 he addressed a group of scholars who had invited him to speak on the relationship of Buddhism to science, philosophy, and religion. He took the opportunity to begin his assault on the many misconceptions of Buddhism that he judged to be prevalent in the West. During his speech, Taixu remarked:

Common people consider Buddhism to be concerned with a negative emptiness. However, this is really not so. Buddhism is concerned with developing our perspectives on human life until they become perfect. Thus, it concerns the never ending development and progress of our cosmological nature. Therefore, Buddhism is most complete, while the final result of the theories of all non-Buddhist schools will, on the contrary, come to nothing.

If we are able to understand the truth concerning the whole universe -- that there is neither birth nor death, beginning nor end -- then we will recognize that if the Absolute is a divine spirit (shen), then we are also divine spirits; if a god (shangdi), then we are also gods; if a Buddha (fo), then we are also buddhas.39

During the final days of September and the early days of October, Taixu focused on his forthcoming lectures but also accepted several invitations to meet with diplomats, with local Buddhist leaders concerned with how better to organize themselves in France, and even with the Roman Catholic archbishop, who wanted to discuss the developing anti-religion movement in China and issues related to religious freedom. On October 14, he delivered an important lecture at the Musee Guimet, sponsored jointly by the Association Franco-Chinoise and Association Francaise des Amis de l'Orient [Franco-Chinese and French Association of Friends of the Orient], entitled "Le Bouddhisme dans l'histoire: Ses nouvelles tendances" (A History of Buddhism and Its New Movements; Ch. Foxue yuanliu ji qi xin yundong), at which he was introduced as "Son Eminence Taixu, President de l'Union Bouddhiste Chinoise." ["His Eminence Taixu, President of the Chinese Buddhist Union."]40

Table 2. The World Buddhist University

World Buddhist University (Shijie fohua daxue)

Secular Studies / Religious Studies

Western Studies / East Asian Studies / Doctrinal Studies / Ethical Studies

Science Department / Religious Studies Department / Nikaya Studies Department / Vinaya Studies Department

Philosophy Department / Political Science Department / Wisdom Studies Department / Meditation Studies Department

Arts and Literature Department / Arts and Literature Department / Yogacara Studies Department / Mantrayana Studies Department

Source: Dongchu, Zhongguo fojiao jindai shi (A History of Modern Chinese Buddhism). 1:302.

Table 3. The World Buddhist Institute

World Buddhist Institute (Shijie foxue yuan)

Religious Research / Doctrinal Research / Practical studies / Attainment studies

The collection and study of religious implements used in Buddhist practice in various countries / Nikaya Buddhist studies, based primarily on Indian and Southeast Asian sources / Vinaya studies, focusing on the bodhisattva precepts / Studies of faith

The editing and study of historical materials on Buddhism from various countries / Mahayana Buddhist studies, based primarily on Indian and Tibetan source4s / Meditational studies, focus on the Chan tradition / Studies of morality

The examination and editing of Buddhist texts from various countries / Chinese Buddhist studies, based on the synthetic schools of China and Japan / Esoteric studies, with extensive research into mantras / Studies of concentration (samadhi)

The preparation of Buddhist literature from various countries for publication / Studies of new European and American forms of Buddhism / Pure Land studies on various heavens and pure lands / Studies of wisdom

Source: Xuming, Taixu dashi shengping shiji (A Record of the Life of the Venerable Master Taixu), 27, and Manzhi and Mochan, eds., Taixu dashi huanyou ji (A Record of the Venerable Master Taixu's World Travel). 141-142.