Defining Modern Buddhism: Mr. and Mrs. Rhys Davids and the Pali Text Society

by Judith Snodgrass

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East

Vol. 27, No. 1, 2007

© 2007 by Duke University Press

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Early Western Buddhist scholarship was archetypically “orientalist” both in the various senses implied by Edward Said’s work on the West’s colonization of knowledge of the Orient and in the proud lineage of the dedicated and immaculate translation and interpretation of Asian-language primary sources. In this article I examine the work of Thomas William Rhys Davids (1843–1922) and Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids (1857–1942), his wife and colleague in scholarship. T. W. Rhys Davids founded the Pāli Text Society in 1881 and served as its chairman until his death in 1922. Caroline, whom he married in 1894, then continued in the position. Together they dominated Pāli studies for sixty years. Their contribution includes the almost complete publication of the Pāli canon, a Pāli dictionary, numerous expository works, and the training of a large number of colleagues and students to perpetuate their influence. More than just pioneers in the field, they have provided the standard interpretation of Pāli Buddhism. They are, to extend Charles Hallisey’s observation, the “inaugural heroes” of academic studies of Buddhism.1 While unquestionably an orientalist construct, the features of Buddhism they documented and validated through their meticulous and dedicated study of Pāli texts remain the basis not only of Western understanding of Buddhism but of many modern Buddhist movements in Asia. They established the parameters of the rational humanist schools of Buddhism that are characteristic of what Donald Lopez has usefully referred to as modern Buddhism.2

Contents

• Helena Petrovna Blavatsky 1

• Sir Edwin Arnold 6

• Henry Steel Olcott 15

• Paul Carus 24

• Shaku Soen 35

• Dwight Goddard 49

• Anagarika Dharmapala 54

• Alexandra David-Neel 59

• D. T. Suzuki 68

• W. Y. Evans-Wentz 78

• T'ai Hsu 85

• B. R. Ambedkar 91We must now turn to the evaluation of means. We must ask whose means are superior and lasting in the long run. There are, however some misunderstandings on both sides. It is necessary to clear them up. Take violence. As to violence, there are many people who seem to shiver at the very thought of it. But this is only a sentiment. Violence cannot be altogether dispensed with. Even in non-communist countries a murderer is hanged. Does not hanging amount to violence? Non-communist countries go to war with non-communist countries. Millions of people are killed. Is this no violence? If a murderer can be killed, because he has killed a citizen, if a soldier can be killed in war because he belongs to a hostile nation, why cannot a property owner be killed if his ownership leads to misery for the rest of humanity? There is no reason to make an exception in favour of the property owner, why one should regard private property as sacrosanct.

The Buddha was against violence. But he was also in favour of justice, and where justice required, he permitted the use of force...

"Does the Tathagata prohibit all war, even when it is in the interest of Truth and Justice?"

Buddha replied. You have wrongly understood what I have been preaching. An offender must be punished, and an innocent man must be freed. It is not a fault of the Magistrate if he punishes an offender. The cause of punishment is the fault of the offender. The Magistrate who inflicts the punishment is only carrying out the law. He does not become stained with Ahimsa. A man who fights for justice and safety cannot be accused of Ahimsa. If all the means of maintaining peace have failed, then the responsibility for Himsa falls on him who starts war. One must never surrender to evil powers. War there may be. But it must not be for selfish ends...."

There are of course other grounds against violence such as those urged by Prof. John Dewey. In dealing with those who contend that the end justifies the means is [a] morally perverted doctrine, Dewey has rightly asked what can justify the means if not the end? It is only the end that can justify the means.

Buddha would have probably admitted that it is only the end which would justify the means. What else could? And he would have said that if the end justified violence, violence was a legitimate means for the end in view. He certainly would not have exempted property owners from force if force were the only means for that end. As we shall see, his means for the end were different. As Prof. Dewey has pointed out that violence is only another name for the use of force and although force must be used for creative purposes a distinction between use of force as energy and use of force as violence needs to be made. The achievement of an end involves the destruction of many other ends, which are integral with the one that is sought to be destroyed. Use of force must be so regulated that it should save as many ends as possible in destroying the evil one. Buddha's Ahimsa was not as absolute as the Ahimsa preached by Mahavira the founder of Jainism. He would have allowed force only as energy. The communists preach Ahimsa as an absolute principle. To this the Buddha was deadly opposed...

As to Dictatorship, the Buddha would have none of it. He was born a democrat, and he died a democrat...

The Bhikshu Sangh had the most democratic constitution. He was only one of the Bhikkus. At the most he was like a Prime Minister among members of the Cabinet. He was never a dictator...

The Communists themselves admit that their theory of the State as a permanent dictatorship is a weakness in their political philosophy. They take shelter under the plea that the State will ultimately wither away. There are two questions, which they have to answer. When will it wither away? What will take the place of the State when it withers away? To the first question they can give no definite time. Dictatorship for a short period may be good, and a welcome thing even for making Democracy safe. Why should not Dictatorship liquidate itself after it has done its work, after it has removed all the obstacles and boulders in the way of democracy and has made the path of Democracy safe. Did not Asoka set an example? He practised violence against the Kalingas. But thereafter he renounced violence completely. If our victor’s to-day not only disarm their victims, but also disarm themselves, there would be peace all over the world...

The Communists have given no answer. At any rate no satisfactory answer to the question what would take the place of the State when it withers away, though this question is more important than the question when the State will wither away. Will it be succeeded by Anarchy? If so, the building up of the Communist State is an useless effort. If it cannot be sustained except by force, and if it results in anarchy when the force holding it together is withdrawn, what good is the Communist State? The only thing which could sustain it after force is withdrawn is Religion. But to the Communists Religion is anathema. Their hatred to Religion is so deep seated that they will not even discriminate between religions which are helpful to Communism and religions which are not. The Communists have carried their hatred of Christianity to Buddhism without waiting to examine the difference between the two. The charge against Christianity levelled by the Communists was two fold. Their first charge against Christianity was that they made people other worldliness and made them suffer poverty in this world. As can be seen from quotations from Buddhism in the earlier part of this tract, such a charge cannot be levelled against Buddhism.

The second charge levelled by the Communists against Christianity cannot be levelled against Buddhism. This charge is summed up in the statement that Religion is the opium of the people. This charge is based upon the Sermon on the Mount which is to be found in the Bible. The Sermon on the Mount sublimates poverty and weakness. It promises heaven to the poor and the weak. There is no Sermon on the Mount to be found in the Buddha's teachings. His teaching is to acquire wealth. I give below his Sermon on the subject to Anathapindika one of his disciples.

Once Anathapindika came to where the Exalted One was staying. Having come, he made obeisance to the Exalted One, and took a seat at one side, and asked, "Will the Enlightened One tell what things are welcome, pleasant, agreeable, to the householder but which are hard to gain."

The Enlightened One having heard the question put to him said "Of such things the first is to acquire wealth lawfully."

"The second is to see that your relations also get their wealth lawfully."

"The third is to live long and reach great age."...

"Thus to acquire wealth legitimately and justly, earn by great industry, amassed by strength of the arm and gained by sweat of the brow is a great blessing. The householder makes himself happy and cheerful and preserves himself full of happiness; also makes his parents, wife, and children, servants, and labourers, friends and companions happy and cheerful, and preserves them full of happiness."...

The Russians are proud of their Communism. But they forget that the wonder of all wonders is that the Buddha established Communism so far as the Sangh was concerned without dictatorship. It may be that it was a communism on a very small scale, but it was communism without dictatorship, a miracle which Lenin failed to do...

It has been claimed that the Communist Dictatorship in Russia has wonderful achievements to its credit. There can be no denial of it. That is why I say that a Russian Dictatorship would be good for all backward countries. But this is no argument for permanent Dictatorship. Humanity does not only want economic values, it also wants spiritual values to be retained. Permanent Dictatorship has paid no attention to spiritual values, and does not seem to intend to. Carlyle called Political Economy a Pig Philosophy. Carlyle was of course wrong. For man needs material comforts. But the Communist Philosophy seems to be equally wrong, for the aim of their philosophy seems to be fatten pigs as though men are no better than pigs. Man must grow materially as well as spiritually. Society has been aiming to lay a new foundation was summarised by the French Revolution in three words: Fraternity, Liberty and Equality. The French Revolution was welcomed because of this slogan. It failed to produce equality. We welcome the Russian Revolution because it aims to produce equality. But it cannot be too much emphasised that in producing equality, society cannot afford to sacrifice fraternity or liberty. Equality will be of no value without fraternity or liberty. It seems that the three can coexist only if one follows the way of the Buddha. Communism can give one but not all.

-- B. R. Ambedkar, Excerpt from "A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West", by Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

• Lama Govinda 98

• R. H. Blyth 106

• Mahasi Sayadaw 116

• Shunryu Suzuki 127

• Buddhadasa 138Buddhadasa (1906-93) was born in southern Thailand, the son of a merchant, and was educated at Buddhist temple schools. It was customary for males in Thailand to be ordained as a Buddhist monk for three months at the age of twenty and then return to lay life. Buddhadasa decided to remain a monk and quickly gained a reputation as a brilliant thinker, meditator and teacher. However, rather than moving through the monastic hierarchy in the capital, he returned home in 1932, after several years of study in Bangkok, to establish a meditation and study centre, which he called Wat Suan Mokkhabalarama (the 'Garden of the Power of Liberation'). Buddhadasa spent most of his life at this forest monastery overlooking the sea. Here the resident monks devoted more time to meditation practice and less time to merit-making activities than did many Thai monks. The centre attracted thousands of guests and visitors each year, with more than a thousand receiving meditation instruction annually.

In addition to his activities as a meditation teacher, Buddhadasa was to become the most prolific author in the history of the Theravada Buddhist tradition, his writing in many cases being transcriptions of lectures given at his monastery. Just as Buddhadasa showed little interest in the administrative programmes of the Thai Buddhist sangha, in his writings he eschewed the more formal style of traditional scholastic commentary in favour of a more informal, and in many ways controversial, approach in which he called many of the more popular practices of Thai Buddhism into question. For example, he spoke out strongly against the practice of merit-making in which laypeople offer gifts to monks in the belief that they will receive material reward in the next life. Although this has traditionally been the dominant form of lay practice, Buddhadasa argued that it only keeps the participants in the cycle of rebirth because it is based on attachment, whereas the true form of giving is the giving up of the self. This is not a solitary pursuit, however. Because of dependent origination, people live in a shared environment connected by social and natural relations. This state is originally one of harmony that has fallen out of balance because of attachment to 'me' and 'mine'.Again we find that the various forms of existing governments are explained as debased copies of the true model or Form of the state, of the perfect state, the standard of all imitations, which is said to have existed in the ancient times of Cronos, father of Zeus.

-- The Open Society and Its Enemies, by Karl R. Popper

By diminishing attachment and craving, both personal and social well-being are achieved in a society in which leaders promote both the physical and spiritual well-being of the people. Buddhadasa calls such a form of government 'dhammic socialism'. In the passage that follows, Buddhadasa argued that the best form of government for small countries such as Thailand is a 'dictatorial socialism' based on classical Buddhist principles, with leadership provided by a king who embodies ten royal virtues.

***

The Buddha developed a socialist system with a 'dictatorial' method. Unlike liberal democracy's inability to act in an expeditious and timely manner, this dhammic dictatorial socialism is able to act immediately to accomplish what needs to be done. This approach is illustrated by the many rules in the vinaya against procrastination, postponement and evasion. Similarly, the ancient legal system was socialistic. There was no way that someone could take advantage of another, and its method was 'dictatorial' in the sense that it cut through confusion and got things done.

Now we need to look more closely at the system of kingship based on the Ten Royal Precepts or Virtues. This is also a form of dictatorial socialism. The best example is King Asoka. Many books about Asoka have been published, in particular concerning the Asokan inscriptions found on rock pillars throughout his kingdom. These were edicts about Asoka's work which reveal a socialist system of government of an exclusively dictatorial type. He purified the sangha by wiping out the heretics, and he insisted on right behavior on the part of all classes of people. Asoka was not a tyrant, however. He was a gentle person who acted for the good of the whole society. He constructed wells and assembly halls, and had various kinds of fruit trees planted for the benefit of all. He was 'dictatorial' in the sense that if his subjects did not do these public works as commanded, they were punished.

After King Asoka gave his orders, one of his officials, the Dhammajo or Dhammamataya, determined if they had been faithfully followed out through all the districts of the kingdom. If he found a transgressor a 'dictatorial' method was used to punish him. The punishment was socialistic in the sense that it was useful for society and not for personal or selfish reasons.

The final piece of evidence supporting King Asoka's method occurred at the end of his life, when all that remained of his wealth was a half of a tamarind seed. Before he died he gave even this away to a monk. What kind of person does such an act -- a tyrant or a socialist? That King Asoka also preserved the ideals of a Buddhist dictatorial socialism is also supported by an examination of his famous rock and pillar edicts.

Socialism in Buddhism, furthermore, is illustrated by the behavior of more ordinary laymen and laywomen. They live moderately, contributing their excess for the benefit of society. For example, take the case of the Buddhist entrepreneur or sresthi. In Buddhism, sresthi are those who have alms houses (Thai: rong than). If they have no alms houses they cannot be called sresthi. The more wealth they have the more alms houses they possess. Do capitalists today have alms houses? If not, they are not sresthi as we think of them during the Buddhist era which was socialistic in the fullest sense. The capitalists during the Buddhist era were respected by the proletariat rather than attacked by them. If being a capitalist means simply accumulating power and wealth for oneself, that differs radically from the meaning of sresthi as one who uses his or her wealth to provide for the well-being of the world.

Even such terms as slave, servant, and menial had a socialistic meaning during the Buddhist era. Slaves did not want to leave the sresthi. Today, however, 'slaves' hate capitalists. Sresthi during the Buddhist era treated their slaves like their own children. All worked together for a common good. They observed the moral precepts together on Buddhist sabbath days. The products of their common labor were for use in alms houses. If the sresthi accumulated wealth, that would be put in reserve for use later in the alms houses. Today things are very different. In those days slavery was socialistic and did not need to be abolished. Slave and master worked for the common good. The kind of slavery which should be abolished exists under a capitalist system in which a master treats slaves or servants like animals. Slaves under such a system always desire freedom, but slaves under a socialist system want to remain with their masters because they feel at ease. In my own case, for example, it would be easier to be a common monk than to bear the responsibilities of being an abbot. Similarly, a servant in a socialist system has an easier life than a master (Thai: nai), and is treated as a younger family member.

In the Buddhist view, sresthi are those who have alms houses, and a great sresthi has many of them. They have enough for their own use and share from their excess. Buddhists have espoused socialism since antiquity, whether at the level of king, wealthy merchant or slave. Most slaves were content with their status even though they could not, for instance, be ordained as monks. They could be released from their obligations, or continue them, as they chose. Slaves were recipients of love, compassion, and care. Thus, one can see that the essence of socialism in those days was pure and totally different from the socialism of today.

Let us look again at the Ten Royal Precepts or Virtues (dasarajadhamma) as a useful form of Buddhist socialism. Most students at secondary and college level have studied the canonical meaning of the dasarajadhamma, and did not find it of much interest. In Buddhism this is called the ten dhamma of kingship: dana (generosity), sila (morality), pariccaga (liberality), ajjava (uprightness), maddava (gentleness), tapo (self-restraint), akkodha (non-anger), avihimsa (non-hurtfulness), khanti (forbearance), avirodhana (non-opposition).

Dana is giving or the will to give; sila is morality, those who possess morality (sila-dhamma) in the sense of being the way things are (prakati) freed from the forces of defilement (kilesa); pariccaga means to give up completely all inner evils such as selfishness; ajjava is truthfulness; maddava is to be meek and gentle toward all citizens; tapo or self-control refers to the fact that a king should always control himself; akkodha means to be free from anger; avihimsa is the dhamma which restrains one from causing trouble to others, even unintentionally; khanti is being tolerant or assuming the burden of tolerance; avirodhana is freedom from guilt. A king who embodies these ten virtues radiates the spirit of socialism. Why need we abolish this kind of kingship? If such a king was a dictator, he would be like Asoka whose 'dictatorial' rule was to promote the common good and to abolish the evil of private, selfish interest.

Let us now look at the way in which the Samuhanimit monastery (wat) in Phumriang District was built as an example of Buddhist dictatorial socialism. An inscription in the monastery tells us that the wat was built during the third reign under the sponsorship of the Bunnag family, and that it was built in four months. To finish the wat in four months called for 'dictatorial' methods. Thousands of people from the city were ordered to help complete the work and occasionally physical punishment was used. The labor force made bricks, brought stones, animals, trees - everything they could. After the work was finished, the head of the monastery in the city who had resided at one of the city wats was forced to be the abbot at Wat Samuhanimit. To be sure, dictatorial methods were used in the establishment of this monastery, but the end result benefited everyone.

The character of the ruler is the crucial factor in the nature of Buddhist dictatorial socialism. If a good person is the ruler, the dictatorial socialism will be good, but a bad person will produce an unacceptable type of socialism. A ruler who embodies the ten royal virtues will be the best kind of socialistic dictator. This way of thinking will be totally foreign to most Westerners who are unfamiliar with this kind of Buddhist kingly rule. A good king is not an absolute monarch in the ordinary sense of that word. Because we misunderstand the meaning of kingship we consider all monarchial systems wrong. The king who embodies the ten royal virtues, however, is a socialist ruler in the most profound or dhammic sense, such as the King Mahasammata, the first universal ruler, King Asoka, and the kings of Sukhodaya and Ayudhaya. Kingship based on the ten royal virtues is a pure form of socialism. Such a system should not be abolished, but it must be kept in mind that this is not an absolute monarchy. In some cases this form of Buddhist dictatorial socialism can solve the world's problems better than any other form of government.

People today follow the Western notion that everyone is equal. Educated people think that everyone should have the right to govern, and that this is a democratic system. However, today, the meaning of democracy is very ambiguous. Let us ask ourselves what the kind of democracy we have had for at least one hundred years has contributed to us as citizens. Questioning this kind of worldly democracy may make us suspect. I, myself, am not afraid to be killed because of rejecting this kind of democracy. I favor a Buddhist socialist democracy which is composed of dhamma and managed by a 'dictator' whose character exemplifies the ten royal virtues (dasarajadhamma). Do not blindly follow the political theories of someone who does not embody the dasarajadhamma system, the true socialist system which can save humankind. Indeed, revolution has a place in deposing a ruler who does not embody the dasarajadhamma, but not a place within a revolutionary political philosophy which espouses violence and bloodshed.

The dasarajadhammic system is absolute in that it depends essentially on one person. It was developed to the point where an absolute monarch could rule a country or, for that matter, the entire world as in the case of the King (raja) Mahasammata. The notion of a ruler (raja) needs to be better understood. The title, raja, was given to the first ruler thousands of years ago when people first became interested in establishing a socialist society. We also need to rethink the notion of caste or class (varna). The ruling class (ksatriya) has come to be despised and people advocate its abolition. Such an attitude ignores the fact that a ruling class of some kind is absolutely necessary; however, it should be defined by its function rather than by birth. For example, there must be magistrates who constitute a part of a special class of respected people.In the representative system, the reason for everything must publicly appear. Every man is a proprietor in government, and considers it a necessary part of his business to understand. It concerns his interest, because it affects his property. He examines the cost, and compares it with the advantages; and above all, he does not adopt the slavish custom of following what in other governments are called Leaders.

-- Rights of Man, by Thomas Paine

Caste or class (varna) should be based on function and duty rather than on birth. Varna determined by inherited class should be abolished. The Buddha, after all, abolished his own varna by becoming a monk and prescribing the abolition of others' inherited class statuses. But class by function and responsibility should not be abolished. It is the result of kamma. For instance, kamma dictates that a king should rule, and that a Brahman should teach or should be a magistrate in order to maintain order (dhamma) in the world. Class in this sense should not be abolished. The ruling class (ksatriya-varna) should be maintained, but as part of the dasarajadhammika system to govern the world.

There was another system of government typical of small countries during the time of the Buddha, e.g. the Sakya and Licchavi, worthy of examination. The Licchavis, for example, were governed by an assembly composed of 220 people of the ksatriya class. The elected head of the assembly acted as a king, having been chosen to rule for a designated period of time, e.g. seven months. The best of those born into the ksatriya class were chosen as members of the assembly. One may imagine how progressive their kingdom was. Such was the Sakya kingdom of the Buddha. Large kingdoms like Kosala could not conquer these small states because they were rooted in dhammic socialism. When they gave up this system of government social harmony was undermined which resulted in their destruction. The Buddha used the Licchavis as an example of a people who followed a socialist style of life careful in personal habits, attentive to the defense of the nation, and respectful of women -- but who departed from this way and were eventually destroyed. Western scholars have not written very much about this ancient type of government in which the king and his assembly ruled by the dasarajadhamma. But this type of government, an enlightened ruling class (ksatriyavarna) based in the dasarajadhamma is, in fact, the kind of socialism which can save the world.

The sort of socialism I have been discussing is misunderstood because of the term, raja. But a ruler who embodies the ten royal virtues represents socialism in the most complete sense -- absolute, thorough, effective -- like King Asoka and other rulers like him in our Thai history. For example, upon careful study we can see that Rama Khamhaeng ruled socialistically, looking after his people the way a father and mother look after their children. Such a system should be revived today. We should not blindly follow a liberal democratic form of government essentially based on selfish greed.

The last point I want to make and one especially important for the future is that small countries like our own should adhere to a system of 'dictatorial dhammic socialism' or otherwise it will be difficult to survive. An illusory democracy cannot survive. Liberal democracy has too many flaws. Socialism is preferable, but it must be a socialism based on dhamma. Such dhammic socialism is by its very nature 'dictatorial' in the sense I have discussed today. In particular, small countries like Thailand should have democracy in the form of a dictatorial dhammic socialism.

An ancient proverb which is rarely heard goes, 'You must ignite the house fire in order to receive the forest fire.' Elders taught their children that they should burn an area around their huts in order to prevent forest fires from burning down their dwellings. If small countries like our own have a dictatorial dhammic socialist form of government, it will be like burning the area around the house in order to protect us from the forest fire. The forest fire can be compared to violent forms of socialism or to capitalism, both of which encompass the world today. A dictatorial dhammic socialism will protect us from being victimized by either capitalism or violent forms of proletarian revolution.

-- Bhikkhu Buddhadasa, 'Dictatorial Dhammic Socialism' in Dhammic Socialism (Bangkok: Thai Inter-religious Commission for Development, 1986), pp. 189-93.

• Philip Kapleau 146

• William Burroughs 154

• Alan Watts 159

• Jack Kerouac 172

• Ayya Khema 182

• Sangharakshita 186

• Allen Ginsberg 194

• Thich Nhat Hanh 201

• Gary Snyder 207

• Sulak Sivaraksa 211

• The Dalai Lama 217

• Cheng Yen 227

• Fritjof Capra 236

• Chogyam Trungpa 244

-- Introduction, Excerpt from "A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West", by Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Lopez’s premise is that there are forms of Buddhism found around the contemporary world—in the West and in Asia—that share sufficient key beliefs and practices to be seen as a new school, a Buddhist sect of the global era. While it is in no way monolithic, its various manifestations have arisen over the past century as a result of Western imperialism and its scholarship, of encounters of traditional Buddhist societies with modernity, and, more recently, of political upheavals that have caused migrations of Buddhist populations to the West. Lopez offers a lineage for the new “sect,” tracing it from Ceylonese Buddhist resistance to missionaries in 1876, through writings of early Theosophists, a selection of familiar Western and Asian practitioners and popularizers, culminating in the culturally hybrid teachings of Chogyam Trungpa, founder of the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado.3 D. T. Suzuki and other major figures in Western writing are awarded a place in the lineage. Oddly, however, the Rhys Davids are not.4 Their absence is underlined by Lopez’s description of modern Buddhism, which encapsulates the interpretation they propagated precisely: “It is ancient Buddhism, and especially the enlightenment of the Buddha 2,500 years ago, that is seen as most modern, as most compatible with the ideals of the European enlightenment that occurred so many centuries later. . . . Indeed, for modern Buddhists, the Buddha knew long ago what Europe would only discover much later.”5 Modern Buddhism is thoroughly humanist. The Buddha is a historical hero who taught “a complete philosophical and psychological system, based on reason and restraint, as opposed to ritual, superstition and sacerdotalism, demonstrating how the individual could live a moral life without the trappings of institutional religion.” 6 Its practice is egalitarian, lay centered, and socially committed, imbued with modernity’s ideals of reason, empiricism, science, universalism, tolerance, and the rejection of religious orthodoxy. It is an understanding of Buddhism that depends on a human founder as a model of the path to personal development.

While no Buddhist questions the historical existence of the Buddha Sakyamuni, until the emergence of modern Buddhism in the mid-nineteenth century he was not seen as the founder of the religion, or as the only Buddha, but as one of a series of Buddhas born into the world to teach the eternal dharma. This is made abundantly clear in the archaeology of Indian Buddhism—the bas-reliefs of Bharhut and ornate gateways of the Sanchi stupas represent previous Buddhas—in its earliest texts and in any number of schools of Buddhism persisting through to the present. T. W. Rhys Davids himself speaks of the tedious repetition of the lives of previous Buddhas that differ only in the details of names and places and the type of tree under which the Buddha attained awakening.7 As he explained, of each parallel incident mentioned the text repeats, “This, in such a case, is the rule.” His explanation of the meaning of “Tathāgata,” one of the most commonly used titles of the Buddha, also makes this point: “Tathāgata is an epithet of the Buddha. It is interpreted by Buddhaghosa . . . to mean that he came to earth for the same purposes, after having passed through the same training in former births, as all the supposed former Buddhas; and that, when he had so come, all his actions corresponded with theirs.”8 The shift in focus to the humanity of the Buddha as Founder of the religion is a defining feature of modern Buddhism, a mark of modernity, the necessary rupture with the past that marks the modern, but it is not one that was necessarily supported by the evidence on which the nineteenth-century scholars in this study based their conclusions.

In this article I revisit the work of T. W. and C. A. F. Rhys Davids to elucidate the social and historical contingencies and discursive practices that gave shape to this humanist Buddhism, to demonstrate the function of the technologies of knowledge and the dynamics of discourse in its formation and dissemination. Their work is useful in this endeavor precisely because their unquestionable dedication, impeccable scholarship, and immense contribution to Buddhist studies and the ongoing esteem in which they are held directs one away from simplistic notions of orientalism as error or colonial denigration of subject cultures. Extending the focus to the Pāli Text Society enables a consideration of Asian agency and participation in the process. It also offers an alternative lineage for modern Buddhism, one equally enmeshed in the East-West encounters of colonialism and modernity but that recognizes the complicity of academic philology and the institutional practices of scholarship in the process.

An alternative lineage for modern Buddhism, one equally enmeshed in the East-West encounters of colonialism and modernity, that recognizes the complicity of political forces in the process.

-- Freda Bedi, by Altruistic World Online Library

Colonial Beginnings

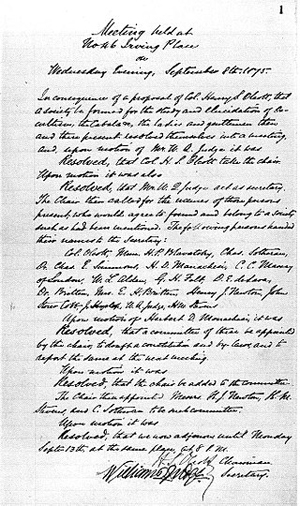

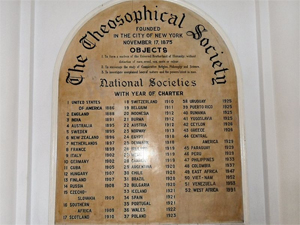

T. W. Rhys Davids’s interest in Pāli began while he was serving in the Ceylon Civil Service (1864–72). His association with Buddhism at this time was incidental—to learn Pāli he had to study with a bhikkhu. His first translation, typical of the historical bias of his time, was in numismatics and epigraphy, an outcome of his posting to the archaeologically rich area of Anuradhapura, and led in 1877 to his Ancient Coins and Measures of Ceylon, which contained the first attempt to date the death of the Buddha.9 He did not write on Buddhism until after his return to Britain, and a modest comment on how little he knew about Buddhism at that time, which is quoted by Ananda Wickremaratne, suggests that he was invited to do so because of popular interest in Buddhism.10 His first book, the highly influential Buddhism: A Sketch of the Life and Teachings of Gautama, the Buddha (1878), was compiled from the material then available in translation.11 This book established his reputation as a Buddhist scholar. It was followed by his translations Buddhist Birth Stories and Buddhist Suttas, both published in 1880.12 During the influential Hibbert Lectures of 1881, he announced the founding of the Pāli Text Society, confidently predicting the publication of the whole of the texts of the Sutta and Abhidhamma Pitakas in “no very distant period.”13 The inaugural committee of management included, among others willing to undertake translation, the Pāli scholars Victor Fausboll, Hermann Oldenberg, and Emile Senart. There was clearly a growing interest and activity in Pāli translation by this time. The formation of the Pāli Text Society institutionalized the study of Buddhism and the interpretation of it, which had begun much earlier. It is necessary therefore to look briefly at the earlier period.

Gotama: The Buddha of Robert Spence Hardy

Beginnings are always problematic, but a key date in this narrative is 1854, the year in which eminent Sanskrit scholar H. H. Wilson, then director of the Royal Asiatic Society, declared the start of Buddhist studies. There was now, he believed, sufficient material from diverse sources to provide “the means of forming correct opinions of Buddhism, as to its doctrines and practices.” 14 The occasion was the publication of three books, two books by the Reverend Robert Spence Hardy, Eastern Monachism (1850) and Manual of Budhism (1853), and the posthumous publication of Eugene Burnouf’s Le lotus de la bonne loi, which appeared about the same time.15 Hardy’s work offered the first systematic account of Theravada Buddhist beliefs and practices and so provided a framework to structure the fragmentary knowledge collected to that date, the work of Alexander Csoma, Brian Houghton Hodgson, George Turnour, and others who were pioneers in the field. Though Hardy’s book was compiled from Singhalese sources rather than from the older and therefore more authoritative Pāli texts, in the absence of these, they were the uncontested authority on the “Buddhism of the South,” and when juxtaposed with Burnouf’s translations of the Sanskrit texts of Northern Buddhism they provided the basis for the cross-cultural comparisons that would reveal the essence of Buddhism, the “reality” concealed under the various local elaborations.16 Buddhist studies, as distinct from Sanskrit and Pāli translations or the missionary study of local practices, could now begin.

A most important feature of Hardy’s work was that it offered the first thorough narrative of the life of the Buddha, a “biography” pieced together by Hardy from various sources, covering his previous births through to his death, cremation, and the distribution of his relics.17 As the designation “Buddhism” suggests, Westerners had assumed, ordering the world through a Christian gaze, that the Buddha, whose image was so prevalent in Buddhist cultures, was the founder of the religion. The search for a life of the Buddha was therefore central to early studies, the logical prerequisite of the scholarly paradigms of the time—the pattern of contemporary Biblical scholarship—that sought to retrieve the very words of the Founder from the sacred texts.18 The search had been frustrated by the fact that the Buddhist texts had been composed for a different purpose. While they recount numerous episodes in the Buddha’s life, they nowhere offered the kind of life narrative Westerners sought in a biography.19

Hardy’s books now seem an unlikely basis for a field of study. He was a Wesleyan missionary to Ceylon from 1825 to 1847 and had studied Singhalese to more efficiently know the religion he aimed to supplant. He was quite explicit about his antipathy to his subject. In 1839 he had published the pamphlet The British Government and Idolatry in Ceylon, a savage attack on Buddhism aimed at undermining the British government’s patronage of “the religion of the country” stipulated in the Kandyan Convention of 1815 that had ceded control of the country to Britain.20 In the preface to Eastern Monachism he wrote: “I ask no higher reward than to be an humble instrument in assisting the ministers of the cross in their combats with this master error of the world, and in preventing the spread of the same delusion, under another guise, in regions nearer home.”21 The “master error” as he saw it was atheism; its “other guise” was materialist philosophy, which in a climate of crisis in the clash between traditional Christian teaching and new developments in science was gathering interest in Europe. This Western crisis would also inform the work of T. W. and C. A. F. Rhys Davids and was a key factor in creating a public interest, an audience for knowledge of Buddhism in the West.

Eastern Monachism opened with an unequivocal statement of the historical humanity of Gautama. “About two thousand years before the thunders of Wycliffe were rolled against the mendicant orders of the west, Gotama Budha [sic] commenced his career as a mendicant in the east, and established a religious system that has exercised a mightier influence upon the world than the doctrines of any other uninspired teacher.”22 By opening with a reference to the fourteenth-century reformer John Wycliffe, Hardy immediately introduced two now familiar features of Western interpretation: the origin of Buddhism as a reaction against the priestcraft and ritual of institutionalized religion, and the role of the Buddha as a social reformer. The body of the work, as the title suggested, compared the Ceylonese sangha (clerical community) to the Roman Catholic clergy and implied that the modern Buddhist teachings are as far removed from the teachings of the Founder, as in his Wesleyan view, the Church of Rome is from the teachings of Jesus. Buddhism, as it is practiced in Ceylon, he wrote, is a degeneration from and ritual elaboration of the Buddha’s original teaching.

Hardy wrote on Buddhism to show its errors, and the greatest error from his perspective was that the Buddha was just a man, a great man, as was Wycliffe, but nothing more than a man. Buddhism, his teaching, was therefore “uninspired,” and left man “unaided.” “Without the . . . lightening of the Divine Eye, the thunder of the Divine Voice . . . the principle of good in man will soon be overwhelmed. . . . With these radical defects”, he concluded, “it is unnecessary to dwell on the lesser.”23

Despite Hardy’s conviction, the humanity of the Buddha was far from decided in the mid-nineteenth century. Wilson, working with the same materials, concluded that even “laying aside the miraculous portions” of the sacred texts, it was, “very problematical whether any such person as Sakya Muni ever lived.” 24 He lists numerous problems such as the discrepancies in dating his life and the lack, at that time, of any archaeological evidence of Kapilavāstu, the site of the Buddha’s early life. What concerned him most was that the names of people and places in the narrative strongly suggested allegorical signification. It was for him “all very much in the style of Pilgrim’s Progress” (247–48). “It seems possible, after all,” he concluded, “that Sakya Muni is an unreal being, and that all that is related of him is as much fiction as is that of his preceding migration, and the miracles that attended his birth, his life, and his departure” (247–48). Wilson was content to leave the question open, concluding that “although we may discredit the actuality of the teacher, we cannot dispute the introduction of the doctrine” (248). In 1854 the historical existence of the Buddha might have been generally assumed but was by no means academically established. This would be the work of the Rhys Davids.

T. W. Rhys Davids: Gautama and the Texts of Buddhism

T. W. Rhys Davids began his Pāli studies almost thirty years later with an unquestioning assumption of the historical reality of the Buddha. His sources were numismatics and epigraphy; gleanings from Turnour’s translation of the chronicle of the transmission of Buddhism to Ceylon, the Mahavamsa; and, significantly, the works of Hardy.25 Basic to Rhys Davids’s analytical approach to the Pāli texts was the knowledge that, even at the most generous estimate, they had been written at least a century or more after the passing of the Buddha. They were the work of his followers from a much later date, shaped by their desire to express their reverence for him.26 They were necessarily of a much later invention, since it was, in his opinion “difficult to believe that even his immediate disciples would have spoken of him in the exaggerated forms in which occasionally he is described.”27 Starting from a conviction of the Founder’s historical reality, he simply dismissed the various names of the Buddha that caused Wilson’s doubt as “honorifi c epithets” inspired by hero worship. The particular problem for him was that “their constant use among the Buddhists tended . . . to veil the personality of Gautama.”28 The Buddha was necessarily external to texts, and the texts were necessarily elaborated.

Rhys Davids’s concern here articulates the difference between traditional Theravada Buddhist focus on the Buddha as teacher of the eternal dharma and model of the path to awakening and the assumptions of the modern humanist scholarship he represents. Like Hardy, he chose to refer to the Buddha as “Gautama.” He rejected the personal name Siddhartha (literally “He who has accomplished his aim”), said to have been given to the Buddha as a child, and the commonly used Sakyamuni, “Sage of the Sakyas,” as obviously later marks of respect. Gautama, by contrast, was a simple family name, and as he explained in a footnote, one that had historical credibility. It was still used in a region that the archaeologist Alexander Cunningham had, by this time, identified with Kapilavāstu.29

This historical displacement between the life of the Buddha and the texts of Buddhism was crucial for T. W. Rhys Davids. The great value of Buddhism to him was that the vast collection of its extant sacred texts preserved a record of the evolution of its religious thought from its development out of Brahmanism in the fifth century BCE right through to the present. He first presented this theme, one that would inform his life’s work, in a public lecture in 1877 titled “What Has Buddhism Derived from Christianity?” which Mrs. Rhys Davids chose to publish in the memorial volume of the Journal of the Pāli Text Society following her husband’s death in 1922.30

After explaining in detail the extraordinary similarities between the two great religions, he established that, not only did Buddhism derive nothing from Christianity, there could have been very little influence in either direction. The similarities therefore were the result of the working out of a universal principle, “the same laws acting under similar conditions” (53). His lesson was that the transformation of Gautama into the Buddha that could be so clearly traced through the texts allowed Christians to see more clearly how Jesus had been transformed into the Christ (52–53). In particular, the Buddhist texts showed how a charismatic human being, a great humanist philosopher who had risen up against the ritual, priestcraft, and institutional religion of his time, had over time been deified by his followers. The extraordinary similarities in their lives, the parallel events, strengthened his case. Buddhism was a “religion whose development runs entirely parallel with that of Christianity, every episode, every line of whose history seems almost as if it might have been created for the very purpose of throwing the clearest light on the most difficult and disputed questions of the origins of the European faith” (52).

This was not only the theme of the first lecture, Mrs. Rhys Davids relays, but a passion he retained throughout his life. She recalls that only weeks before his death he encouraged three Japanese students who visited him to follow the path: “Can you trace in the history of your Buddhism,” he asked, “at what time its votaries began to ascribe divine attributes and status to the Buddha? This is worth your investigating.”31 It was the basis of the Hibbert Lectures and recurs throughout his work. Both Rhys Davids use the name Gautama (alternately Gotama) very pointedly to emphasize that the hero was a man. The title “Buddha” was for them evidence of precisely the deification process they worked to expose, the process whereby “Jesus, who recalled man from formalism to the worship of God, His Father and Their Father, became the Christ, the only begotten son of God Most High, while Gotama, the Apostle of Self-Control and Wisdom and Love, became the Buddha, the Perfectly Enlightened, Omniscient one, the Saviour of the World.”32 Buddhism was, to use T. W. Rhys Davids’s expression, “a mirror which allowed Christians to see themselves more clearly.”33 As a foreign religion its very “otherness” provided the emotional distance, the unfamiliarity, and the lack of attachment necessary for people to be able to see how the process of the deification of a great man and the manufacture of sacred texts operated. The principle could then be applied to reveal how the words of Jesus, his humanist morality, had similarly become obscured and sacralized through the well-intentioned, and thoroughly natural, elaborations of his disciples.

It was a call for reform within his own society and offered a solution to the question of the time: what does Christianity mean in an age of science that calls into question “its divine origin and supernatural growth”?34 His consistent refrain was that Christianity, like any other religion, should be able to stand scientific scrutiny. 35 In the Hibbert Lectures delivered in the series Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion in 1881, he specifically compared the Buddha to the philosophers of the European Enlightenment.36 In the preface to his translation of the Dhamma Kakka Ppavattana Sutta (1880), he wrote:

When after many centuries of thought a pantheistic or monotheistic unity has been evolved out of the chaos of polytheism . . . there has always arisen at last a school to whom theological discussions have lost their interest, and who have sought a new solution to the questions to which the theologies have given inconsistent answers, in a new system in which man was to work out here, on earth, his own salvation. It is their place in the progress of thought that helps us to understand how it is that there is so much in common between the Agnostic philosopher of India, the Stoics of Greece and Rome, and some of the newest schools in France and Germany and among ourselves.37

This same quotation is reproduced in the memorial volume forty-two years later. In this scheme the Buddha plays various roles. First he is equated with Jesus as a humanist teacher and founder of a religion, rising up against Brahmanism just as Jesus rejected Judaism. The Buddha, Jesus, and the Enlightenment thinkers all reacted against the ritual and institutional trappings of religion. Developing this scheme, Rhys Davids likens Mahayana Buddhism, a later development, to the Church of Rome. The quotation above associates the Buddha and Jesus with the philosophies and Stoics as agnostics, people “for whom theological discussions have lost their interest,” at a time when “theologies have given inconsistent answers”—such as Rhys Davids believed they were in nineteenth-century Christendom— people who “seek a solution in [a] secular system of self-reliance.”38 They were examples of people seeking a solution in a secular system of self-reliance. T. W. Rhys Davids used the history of Buddhism to establish the idea of a universal pattern of evolution, something that must inevitably unfold. By presenting original Buddhism, Gautama’s humanist philosophy, as the pinnacle of religious thought in India and demonstrating its affinity with nineteenth-century speculation, Rhys Davids proposed that post-Enlightenment secularized Protestant Christianity was the culmination of religious evolution in the West. That is, the new developments in European philosophy, far from being a threat to orthodox religion, the “master error” as Hardy and his colleagues saw them, were the pinnacle of its evolution.

Hardy humanized Gautama to demonstrate the inadequacy of an ethical system that did not depend on God, and though his books fell into obscurity after those of Rhys Davids appeared, his position continued to be argued by fellow Christian defenders such as Barthelemy Saint-Hilaire. As the first line of his book The Buddha and His Religion declared, “In publishing this book I have but one purpose in view: that of bringing out in striking contrast the beneficial truths and greatness of our spiritualistic beliefs.”39 He, like Hardy, was alarmed by the growing interest in atheistic and agnostic ideas and used Buddhism to demonstrate the inadequacies of a Godless system. However, the positions of the advocates of free thought and of its enemies both insisted on and depended on the Buddha’s being nothing more than a man. “In the whole of Buddhism there is not a race of God. Man, completely isolated, is thrown upon his own resources,” wrote Saint-Hilaire.40 “Agnostic atheism was the characteristic of the [Buddha’s] system of philosophy,” wrote Rhys Davids.41 The difference was that Saint-Hilaire’s statement was a condemnation; Rhys Davids’s was one of approval. Their contest over the future of Christianity in an age of science reinforced the humanity of Gautama. Though their aims are diametrically opposed, their contest confirmed, contrary to Asian traditions and the evidence of the texts, that the Buddha was nothing more than a man.42