by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/20/20

Of the Lodge of the Blue Star and the group around the enigmatic weaver, nothing further can be said. But the Viennese Theosophists who kept such vigilant watch over their younger brothers in mysticism and who directed them to their chosen guru merit closer attention. Their leading spirit was Friedrich Eckstein, a gray eminence of Viennese cultural life, who published almost none of his occult work but whose private lectures seem to have exercised considerable influence on those -- like Gustav Meyrink -- who heard them. [32]

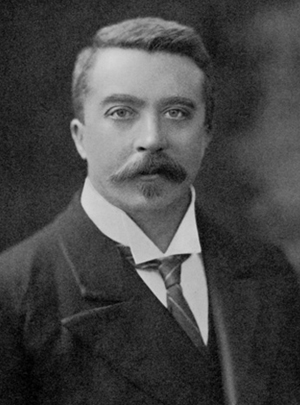

Friedrich Eckstein was born about 1860, the son of a paper manufacturer near Vienna. His interest in mysticism and the occult began almost as early as was possible for Central Europe. At the age of twenty he met Dr. Oscar Simony, a Dozent at Vienna University, whose speciality was number theory.

Simony was concerned with the possibility of further mathematical dimensions and, accordingly, followed with interest the experiments of Professor Zollner of Leipzig, who postulated a fourth dimension of space. Zollner became ensnared by spiritualism through his keenness to prove the existence of his fourth dimension and interpreted the feats performed by the Spiritualist medium Henry Slade on the basis of spirits operating in this hypothetical area. In 1879 Zollner published the third part of his Scientific Essays embodying his experiments with Slade. The consequent furor naturally concerned Simony, who persuaded his old friend Lazar, Baron Hellenbach (a speculative metaphysician and the leading Austrian spiritualist) to bring Slade to Vienna so that he could test Professor Zollner's conclusions for himself. Hellenbach's proteges were notoriously unsuccessful: the baron had once had to undergo the ignominy of seeing the Archduke Johann unmask the medium Harry Bastian. [33] Simony had no luck with Bastian and little with Slade, who broke control during the seance, although apparently he succeeded temporarily in making a table vanish.

The mathematician -- who was chiefly interested in refuting Zollner's theory of the fourth dimension -- concocted a theory that mediums possessed abnormal muscular development and that the electrical energy in their peculiar muscular contractions could produce the phenomena attributed to the spirits. [34] According to their original project, Slade was to have stayed with Friedrich Eckstein during the period of Simony's experiments, but he refused to come unaccompanied, and as the object of the plan had been to prevent any possibility of confederacy, the scheme was dropped. Eckstein's first encounter with the miraculous was unfortunate. Shortly afterwards he and Simony visited the distinguished British scientist Lord Rayleigh, who was at that time living in Vienna, and recounted their experiences. Rayleigh claimed to have seen Indian ascetics move objects from a distance, and Simony asked how he explained this. Rayleigh answered that it was obviously the work of the spirits, and to the astonished query of his visitors he replied that he believed in spirits because he saw them. [35]

Eckstein determined that he would discover whether there were grounds for such belief and decided to join the newly founded Theosophical Society. He corresponded with Theosophists everywhere and traveled to England, where he met H. P. Blavatsky, Colonel Olcott, A. P. Sinnett, and the retinue of Indian members who accompanied the leading Theosophists to Europe on their visit of 1884. He brought back with him a whole library of occult works. Meanwhile, it became clear to him and Simony that in order to test mediums satisfactorily they would have to become experts in sleight-of-hand rather than in esoteric philosophy. The mathematician's interest in the spirits waned after a substantial rebuff dealt his career when he had rashly expressed his misgivings about mediums at the dinner table of an influential Excellenz. Eckstein, on the other hand, although always circumspect in his occult dealings, progressed from primitive spiritualist phenomena to an abiding interest in occult philosophy. He visited H. P. Blavatsky at Ostend not long before her death, and in the early 1890s he went to live for a few months in London to carry out some business in connection with his profession as a chemist. He had a laboratory in the Victoria Docks, was appalled by the British habit of commuting -- he lived in South Kensington -- and was disgusted by bank holidays. At the same time he was closely in contact with Annie Besant and the "esoteric Christian" Edward Maitland; he became particularly friendly with Herbert Burrows and was able to soothe his disturbed nerves with a Theosophical vegetarian picnic near Maidenhead, at which Mohini M. Chaterji gave a talk on the Bhagavad Gita. It was largely through Eckstein's agency that the Vienna Theosophical Society came into existence and it was probably his directing hand that hovered over the Prague Lodge of the Blue Star. [36]

It is of great importance to understand the sort of circles in which Eckstein moved and in which his Theosophy found a ready welcome. With the alteration of time and place, these were very like the artistic coteries of Symbolist Paris, or the similar groups on the fringes of the English Decadence in which the occult revival found its earliest supporters. Instead of Baudelaire, however, the Grand Master of the idealistic Underground in the German-speaking countries was quite naturally Richard Wagner. The composer-playwright's handling of myth coincided with "esoteric" interpretations favored by the occultists. [37] His early setting of the occultist Bulwer Lytton's novel Rienzi gave an obvious clue to budding mystics. In 1880, just at the time when Eckstein became interested in spiritualism and belonged to the central clique of the Viennese idealists, the Bayreuth Master wrote an essay entitled Religion and Art which had the profoundest effect on the Progressive youth which sat at his feet, and particularly on Eckstein's immediate circle. [38]

Religion and Art is in many ways the synthesis of all the goals of the Progressive Underground in the period before the First World War. Wagner called for Art's return to its high vocation of symbolically expressing divine truth, and he announced his program to redeem the world from materialism by the practice of symbolically conceived music. He also praised the ecstatic rites of the American Shakers and gave expression to the underlying anxiety which afflicted many of his readers. "The deepest basis of every true religion we see now in the knowledge of the transitoriness of the world, and arising from this, the positive instruction to free oneself from it." The composer's vegetarianism and his opposition to vivisection place him directly in the category of the Progressive Underground, and his vision of the coming regeneration of man matched the apocalypses of the greatest enthusiasts. He castigated the hypocrisy rampant among his fellow vegetarians. There were those who "set the basic precondition of the problem of regenerating the human race firmly in view." But "from a few superior members is heard the complaint that their comrades have taken up abstaining from flesh merely from personal consideration of diet, and in no way coupled with it the great ideals of regeneration which they must approach if the organization wants to win power." [39] There was to be a league of noble spirits pledged to redeem mankind from its fall through the achievement of individual salvation. Of such spirits, Friedrich Eckstein was among the most possessed. For the first performance of Parsifal he made the journey to Bayreuth on foot; and there was a legend -- which was not in fact true -- that he had gone in sandals, like Tannhauser. [40]

At the end of the 1870s a favorite rendezvous of Eckstein's group of young Viennese idealists was a vegetarian restaurant on the corner of Wallnerstrasse and Fahnengasse. Here they met in a gas-lit cellar to talk of Pythagoras, the Essenes, the Neo-Platonists, therapeutics, and the evils of flesh eating. "Ever and again there swam before us the vision of Empedocles of a golden age in which the greatest sacrilege for men would be 'To take life and stuff onesself with noble elements.'" The group consisted of a typical collection of Bohemians. Eckstein's description of the scene gives substance to the rumors of his Wagnerian pilgrimage. "It was mostly young people who met there and took part in the collective exchange of views: students, teachers, artists and followers of the most diverse professions. While I myself, like several of my closest friends went summer and winter almost completely clad in linen, according to the theories of Pythagoras, others appeared clothed in hairy garments of natural coloring. And if you add to this that most of us had shoulder-length hair and full beards, our lunch-table might have reminded an unselfconscious spectator not a little of Leonardo's Last Supper." The spiritual descendants of this lunch-table are everywhere. To this circle belonged two later Staatsprasidenten as well as the young Hermann Bahr and the Polish poet Siegfried Lipiner, who was in correspondence with Nietzsche. Victor Adler, the founder of the Social Democratic Party, occasionally came. Gustav Mahler turned up, and Eckstein's future roommate, the composer Hugo Wolf, met the Pythagorean Theosophist at his vegetarian Stammtisch. For the first performance of Parsifal in the summer of 1882, the group met at Bayreuth. In Vienna, another rendezvous was the Cafe Griensteidl on the Michaelerplatz, known locally because of its clientele as Megalomania Cafe. The crowning success of these young irrationalists was their summer colony of the year 1888, when they took the Schloss Bellevue at Grinzing and filled it even fuller with eccentricity than the Cafe Griensteidl. [41]

To the Schloss came the feminist Marie Lang and her husband Edmund (both at the center of Theosophical gatherings and the protectors of Hugo Wolf). Friedrick Eckstein's friend from student days, Rosa Mayreder, who was to become another leading protagonist of women's rights, developed during the summer a friendship with Hugo Wolf that led to their collaboration on the opera Der Corregidor. Other visitors were Carl, Graf zu Leiningen-Billigheim, a young diplomat who had attached himself to Eckstein because of his acquaintance with H. P. Blavatsky, and the dubious Theosophist Franz Hartmann, who received unusual visitors from all parts of the world and had already presumed on Eckstein's hospitality for a whole year immediately after his return from India. Marie Lang cooked vegetarian meals. Wolf composed Lieder. Theosophy was the main topic of conversation. [42]

In Vienna, as in the rest of the world, the more occult aspects of Theosophy -- the elaborate cosmology, the miracles, the letters from Mahatmas -- went hand in hand with the "progressive" in social thought. Indeed, there was a necessary association between all idealistic forms of opposition to that which existed. As Leiningen-Billigheim saw it: "In the middle of the chaotic pattern of pleasure-seeking and covetousness, error, arrogance, self-deception, and cowardice, the idealistic point of view once more arises as a helpful and ultimately victorious force." [43] It is symptomatic of the climate in which he spoke that the title of the essay from which these general observations are taken is "What is Mysticism?" and that it was published in a Theosophical series. Against the common enemy all idealists united; and, some of those bent on restructuring the world would adopt some portion of Theosophy as a concession to their religious impulses. Theosophy was Progressively respectable; often Christianity was not.

It is worth examining some of these associates of Eckstein. Hugo Wolf was a composer of the Wagnerian school; Eckstein, who had private means and musical interests -- he was the continual companion and unofficial private secretary to the aging Bruckner -- offered to finance the publication of Wolf's Lieder. This proved not to be necessary; but the Theosophist and the composer lived together for a period. Wolf's biographer has described their friendship: "Eckstein's knowledge was encyclopaedic: his rooms were lined from floor to ceiling with books and scores. They discussed Parsifal together in relation to German and Spanish mysticism, Palestrina's masses, freemasonry, vegetarianism, and various oriental subjects." After the summer colony at Grinzing, Wolf and Eckstein left once more for Parsifal at Bayreuth on the Wagner-Verein's special train. Together they hunted all the way through Swedenborg's Arcana Coelestia for the sources of Berlioz's Hellish language in the Damnation of Faust.

With Hermann Bahr, the leading critical exponent of Expressionist theories, Eckstein maintained a relationship through discussions on metaphysics -- often in a three-handed commerce with Hugo von Hoffmansthal. Bahr had arrived in Vienna in 1887 direct from a Paris in which the mystical was rampant and Rosicrucian Orders revived. As he wrote, "every student made himself out a Paracelsus in front of his grisette; seriously or half in fun there was everywhere an anxious yearning vers les au-dela-mystiques." He found a home from home in the Cafe Griensteidl. Bahr gave thanks that he had gone to Paris when he did; for there, he thought, the spirit of the 18th century was finally being overturned. In the Socialist Victor Adler, whom he had known from Berlin, he saw something of the same process of "spiritualization" -- the Marxist was becoming an idealist. [44] Even the feminist Rosa Mayreder displayed what has seemed to at least one commentator her own sort of mysticism in which theories of the respective roles of the sexes can be compared to the alchemical fusion of opposites. [45]

This milieu will become of crucial importance when we come to consider the origins of psychoanalysis and the early work of Freud.

-- The Occult Establishment, by James Webb

Frederick Eckstein

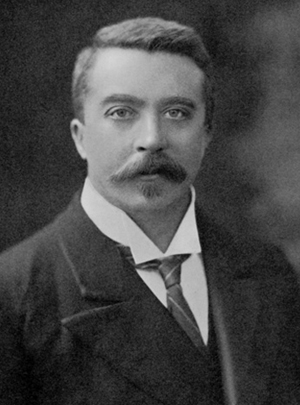

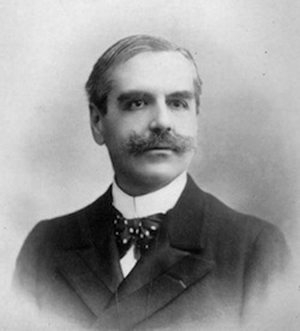

Frederick Eckstein (February 17, 1861 in Perchtoldsdorf, Lower Austria – November 10, 1939 in Vienna) was an Austrian polymath, [Industrialist], theosophist and a friend and temporary co-worker of Sigmund Freud. Emil Molt states: 'He was the benefactor of Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf, indeed the right arm of Bruckner, taking care that affairs went smoothly. He was a world traveller, had mastered Jui-jitsu and taught himself all sorts of difficult tricks. The story went around that he had trained himself to jump off a fast moving train without getting hurt. He too, was a highly gifted mathematician and a learned man in many respects.'

Also the husband of fellow theosophist and writer Bertha Diener, Eckstein's penchant for occultism first became evident as a member of a vegetarian group which discussed the doctrines of Pythagoras and the Neo-Platonists in Vienna at the end of the 1870s. His esoteric interests later extended to German and Spanish mysticism, the legends surrounding the Templars and the freemasons, Wagnerian mythology and oriental religions. In 1889, in the week after the tragedy at Mayerling, in which Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria, and his mistress were found dead in mysterious circumstances, he and his friend, the composer Anton Bruckner (for whom he also served as private secretary) traveled to the monastery of Stift Heiligenkreuz to ask the abbot there for details of what happened.[1]

Eckstein's book on Anton Bruckner was published in 1923.[2]

References

1. Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (1992). The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-3054-X.

2. Erinnerungen an Anton Bruckner by Friedrich Eckstein, 1923, republished by Severus, 2013 ISBN 3863474961

Emil Molt 'The life and times of Rudolf Steiner'

*************************

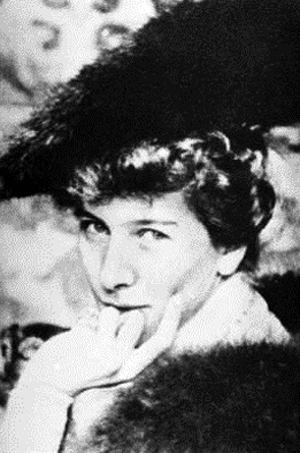

Bertha Eckstein-Diener [Helen Diner] [Ahasvera] [Sir Galahad]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/20/20

Bertha Eckstein in 1902

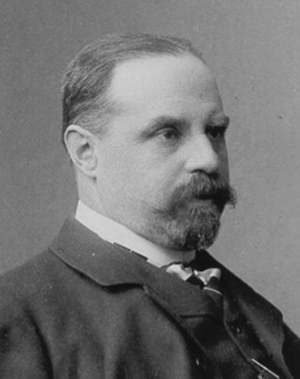

Bertha Eckstein-Diener (March 18, 1874, Vienna – February 20, 1948, Geneva), also known by her American pseudonym as Helen Diner, was an Austrian writer, travel journalist, feminist historian and intellectual. Her book Mothers and Amazons (1930), was the first to focus on women's cultural history. It is regarded as a classic study of Matriarchy.[1]

She was a member of the "Arthurians," a group of European intellectuals active in the 1930s, each of whom adopted a name from Arthur's Round Table (Diner was Sir Galahad). Each member undertook to research an area of knowledge hitherto little known to Western culture. Diner set out to document a feminist history of women, and infused her book Mothers and Amazons (Mütter und Amazonen) with lyrical and poetic language.[1]

Life

Bertha Diener came from a middle-class family and received a higher education. Against the will of her parents, she married the polymath Friedrich Eckstein, a Viennese scholar and industrialist, in 1898. Like her husband, she was a member of the Vienna Lodge of the Theosophical Society Adyar (Adyar-TG). The couple received in their home at this time such notables as Karl Kraus, Adolf Loos, and Peter Altenberg. In 1904 Bertha left her husband and her son Percy (born 1899) and began her travels which took her to Egypt, Greece, and England. The couple finally divorced in 1909 and Frederick Eckstein died in 1939 at the age of 78.

Her 2nd son, Roger (born 1910) was fathered by Theodore Beer, but was placed with a foster family and did not make contact again with his mother until 1936 by letter and in person only in 1938 in Berlin. From 1919 Diener lived in Lucerne, Switzerland. Diener initially wrote under the pseudonym Ahasvera (roughly translated as "Perpetual traveler").[2] Her best-known works were published under the name Sir Galahad, from the knights of King Arthur. Besides her books, she wrote a series of articles for newspapers and magazines and translated three works of American journalists and the esoteric writer Prentice Mulford.

Between 1914 and 1919 she wrote Kegelschnitte Gottes, about the situation of women during that period. From 1925 to 1931, she worked on Mütter und Amazonen, a women-focused cultural history, based on the work of Johann Jakob Bachofen.

She died aged 73 on 20 February 1948 in Geneva, five weeks after an operation. Her last work, a cultural history of England, remained unfinished.

Works

Unless otherwise indicated, the works first appeared under the pseudonym Sir Galahad.

• Im palast des Minos (In the Palace of Minos), Munich: Albert Langen, 1913. 118 pp. 2nd ed., 1924.

• (tr.) Der Unfug des Sterbens: ausgewählte Essays by Prentice Mulford. Munich: Langen, [1920].

• Die Kegelschnitte Gottes; Roman (The Conic Sections of God: Novel), Munich: Albert Langen, 1921. 546 pp. 2nd ed., 1926; 3rd ed., 1932.

• (tr.) Das Ende des Unfugs: ausgewählte Essays by Prentice Mulford. Munich: Albert Langen, 1922.

• Idiotenführer durch die russische Literatur (Idiot's Guide to Russian literature). Munich: Albert Langen, 1925. 163 pp.

• Mütter und Amazone: ein Umriss weiblicher Reiche (Mothers and Amazons: an outline of female empires), Munich: Albert Langen, 1932. 305 pp. Various later eds., from 1981 by Ullstein in paperback, with the subtitle Liebe und Macht im Frauenreich (love and power in the rule of women). ISBN 3-548-35594-3. Translated into English by John Philip Lundin as Mothers and Amazons: the first feminine history of culture, New York: Julian Press, 1965. Introduction by Joseph Campbell.

• Byzanz; von kaisern, engeln und eunuchen (Byzantium. Of emperors, angels and eunuchs), Leipzig and Vienna: Tal, 1936. 318 pp. Translated into English by Eden and Cedar Paul as Emperors, angels, and eunuchs: the thousand years of the Byzantine Empire, London: Chatto & Windus, 1938. US edition published as Imperial Byzantium, 1938.

• Bohemund: ein Kreuzfahrer-Roman (Bohemond: a Crusader novel), Leipzig: Goten-Verlag Herbert Eisentraut, 1938. 291 pp.

• (as Helen Diner) Seide : eine kleine Kulturgeschichte (Silk: a small cultural history), Leipzig: Goten-Verlag H. Eisentraut, 1940. 259 pp. 2nd ed., 1944; 3rd ed., 1949.

• Der glückliche Hügel; ein Richard-Wagner-Roman (The lucky hill: a Richard Wagner novel), Zürich: Atlantis, 1943. 366 pp.

Notes

1. Brooklyn Museum Dinner party database

2. Collection of essays published Munich,1924, by Albert Langen Verlag für Literatur und Kunst, as Der Unfug des Sterbens : ausgewählte Essays, von Prentice Mulford ; bearbeitet und aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Sir Galahad, authors: Mulford, Prentice, 1834-1891. ; Eckstein-Diener, Bertha Helene, (pseudonyms, "Ahasvera", "Sir Galahad", "Helen Diner"), 1874-1948.[1]

References

• Helen Diner Entry at the Brooklyn Museum Dinner Party database of notable women. Accessed March 2008

• Works at the German National Library Index[permanent dead link]

• Eckstein, Bertha at the Aeiou Encyclopedia, Austria. Accessed March 2008

• Sibylle Mulot-Déri: Sir Galahad. Porträt einer Verschollenen, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt 1987, 283 S. (vergriffen) ISBN 3-596-25663-1