by Encyclopedia.com

Accessed: 8/21/20

T. W. Rhys Davids’s interest in Pāli began while he was serving in the Ceylon Civil Service (1864–72). His association with Buddhism at this time was incidental—to learn Pāli he had to study with a bhikkhu. His first translation, typical of the historical bias of his time, was in numismatics and epigraphy, an outcome of his posting to the archaeologically rich area of Anuradhapura, and led in 1877 to his Ancient Coins and Measures of Ceylon, which contained the first attempt to date the death of the Buddha.9 He did not write on Buddhism until after his return to Britain, and a modest comment on how little he knew about Buddhism at that time, which is quoted by Ananda Wickremaratne, suggests that he was invited to do so because of popular interest in Buddhism.10 His first book, the highly influential Buddhism: A Sketch of the Life and Teachings of Gautama, the Buddha (1878), was compiled from the material then available in translation.11 This book established his reputation as a Buddhist scholar. It was followed by his translations Buddhist Birth Stories and Buddhist Suttas, both published in 1880.12 During the influential Hibbert Lectures of 1881, he announced the founding of the Pāli Text Society, confidently predicting the publication of the whole of the texts of the Sutta and Abhidhamma Pitakas in “no very distant period.”13 The inaugural committee of management included, among others willing to undertake translation, the Pāli scholars Victor Fausboll, Hermann Oldenberg, and Emile Senart. There was clearly a growing interest and activity in Pāli translation by this time. The formation of the Pāli Text Society institutionalized the study of Buddhism and the interpretation of it, which had begun much earlier. It is necessary therefore to look briefly at the earlier period.

-- Defining Modern Buddhism: Mr. and Mrs. Rhys Davids and the Pali Text Society, by Judith Snodgrass

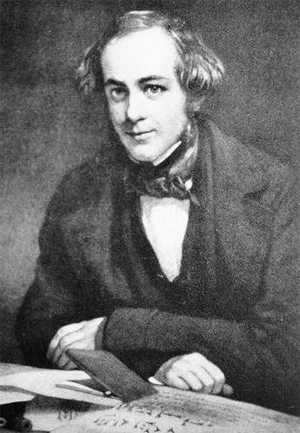

OLDENBERG, HERMANN (1854–1920), German Sanskritist, Buddhologist, and historian of religions. Born in Hamburg on October 31, 1854, the son of a Protestant clergyman, Hermann Oldenberg completed doctoral studies in classical and Indic philology in 1875 at the University of Berlin with a dissertation on the Arval Brothers, an ancient Roman cult fraternity.

Arval Brethren

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

Priesthoods of ancient Rome

Flamen (250–260 CE)

Major colleges: Pontifices · Augures · Septemviri epulonum

Quindecimviri sacris faciundis

Other colleges or sodalities: Fetiales · Fratres Arvales · Salii

Titii · Luperci · Sodales Augustales

Priests: Pontifex Maximus · Rex Sacrorum

Flamen Dialis · Flamen Martialis

Flamen Quirinalis · Rex Nemorensis

Curio maximus

Priestesses: Virgo Vestalis Maxima

Flaminica Dialis · Regina sacrorum

Related topics: Religion in ancient Rome · Imperial cult

Glossary of ancient Roman religion

Gallo-Roman religion

In ancient Roman religion, the Arval Brethren (Latin: Fratres Arvales, "Brothers of the Fields") or Arval Brothers were a body of priests who offered annual sacrifices to the Lares and gods to guarantee good harvests.[1] Inscriptions provide evidence of their oaths, rituals and sacrifices.

Origin

Roman legend held that the priestly college was originated by Romulus, first king of Rome, who took the place of a dead son of his nurse Acca Laurentia, and formed the priesthood with the remaining eleven sons. They were also connected originally with the Sabine priesthood of Sodales Titii who were probably originally their counterpart among the Sabines. Thus it can be inferred that they existed before the founding of the city.[2] There is further proof of the high antiquity of the college in the verbal forms of the song with which, down to late times, a part of the ceremonies was accompanied, and which is still preserved.[3] They persisted to the imperial period.

Structure and duties

Arval Brethren formed a college of twelve priests, although archaeologists have found only up to nine names at a time in the inscriptions. They were appointed for life and did not lose their status even in exile. According to Pliny the Elder, their sign was a white band with the chaplet of sheaves of grain (Naturalis Historia 18.2).

The Brethren assembled in the Regia. Their task was the worship of Dea Dia, an old fertility goddess, possibly an aspect of Maia or Ceres. On the three days of her May festival, they offered sacrifices and chanted secretly inside the temple of the goddess at her lucus the Carmen Arvale. The magister (master) of the college selected the exact three days of the celebration by an unknown method.

The celebration began in Rome on the first day, was transferred to a sacred grove outside the city wall on the second day and ended back in the city on the third day.[4] Their duties included ritual propitiations or thanksgivings as the Ambarvalia, the sacrifices done at the borders of Rome at the fifth mile of the Via Campana or Salaria (a place now on the hill Monte delle Piche at the Magliana Vecchia on the right bank of the Tiber). Before the sacrifice, the sacrificial victim was led three times around a grain field where a chorus of farmers and farm-servants danced and sang praises for Ceres and offered her libations of milk, honey and wine.

Archaic traits of the rituals included the prohibition of the use of iron, the use of the olla terrea (a jar made of unbaked earth) and of the sacrificial burner of Dea Dia made of silver and adorned with grassy clods.

Portrait of Lucius Verus as an Arval Brother (ca. 160 AD)

Restoration of the priesthood

The importance of Arval Brethren apparently dwindled during the Roman Republic, but emperor Augustus revived their practices to enforce his own authority. In his time the college consisted of a master (magister), a vice-master (promagister), a priest (flamen), and a praetor, with eight ordinary members, attended by various servants, and in particular by four chorus boys, sons of senators, having both parents alive. Each wore a wreath of corn, a white fillet and the toga praetexta. The election of members was by co-optation on the motion of the president, who, with a flamen, was himself elected for one year.[3]

After Augustus' time emperors and senators frequented the festivities. At least two emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Elagabalus, were formally accepted as members of the Brethren. The first full descriptions of their rituals also originate from this time.

It is clear that, while the members were themselves always persons of distinction, the duties of their office were held in high respect. And yet no mention of them occurs in the writings of Cicero or Livy, and that literary allusions to them are very scarce. On the other hand, we possess a long series of the acta or minutes of their proceedings, drawn up by themselves, and inscribed on stone. Excavations, commenced in the 16th century and continued to the 19th, in the grove of the Dea Dia, yielded 96 of these records from 14 to 241 AD.[3] The last inscriptions (Acta Arvalia) about the Arval Brethren date from about 325 AD. They were abolished along with Rome's other traditional priesthoods by 400 AD.

References

1. "Arval Brothers on Britannica". Retrieved August 20, 2012.

2. Aulus Gellius VII 7, 7; Pliny XVII 2, 6.

3. One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Arval Brothers". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 711.

4. Chisholm 1911.

Further reading

Piganiol, André. Observations sur le rituel le plus récent des frères Arvales. In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 90ᵉ année, N. 2, 1946. pp. 241-251. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/crai.1946.77986]; http://www.persee.fr/doc/crai_0065-0536 ... 90_2_77986

He submitted his habilitation thesis at Berlin in Sanskrit philology in 1878, going on to become professor at the University of Kiel in 1889, and then at Göttingen from 1908 until his death on March 18, 1920.

Publishing an edition and translation of the Śāṅkhayana Gṛhyasūtra in 1878, the young Oldenberg then turned his attention to the Pali Buddhist texts; and it is due to him as much as to any single scholar that serious inquiry into these materials was begun. Previous decades of nineteenth-century European Buddhist research had focused on Mahāyāna Sanskrit (and Tibetan) texts, through which the historical Buddha and the early history of Buddhism were only dimly apparent. Oldenberg edited and translated into English the important Pali chronicle, the Dīpavaṁsa, in 1879; he also edited the Vinaya Piṭaka ("discipline basket") of the Pali Tipiṭaka (1879–1883), then published English translations of these texts (1881–1885) with T. W. Rhys Davids, founder of the Pali Text Society. The signal publication of this period of intense research on Buddhism is his Buddha: Sein Leben, seine Lehre, seine Gemeinde (1881), written when he was only twenty-six, and "perhaps the most famous book ever written on Buddhism" (J. W. de Jong, Indo-Iranian Journal 12, 1970, p. 224).

While Oldenberg's active interest in Buddhist studies never flagged, Buddhism was for him one dimension of what was to be his Lebenswerk: nothing less than the systematic examination of India's earliest religious history. Indeed, his achievements in Vedic studies are—if this is possible—even more consequential than his contributions to Buddhist studies. Taken together, his Die Hymnen des Rigveda (1888), Die Religion des Veda (1894), and Ṛgveda: Textkritische and exegetische Noten (1909–1912) constitute a triptych of enormous and continuing importance for research on the form, meters, and textual history of the Ṛgveda Samhitā. Further, his translations of several Vedic Gṛhyasūtras (sutras on domestic religious ceremonies), his book-length studies on the Brāhmaṇas and the Upaniṣads, and his numerous articles on Vedic topics complete an imposing legacy of meticulous scholarship.

Through Hermann Oldenberg's efforts, the sustained historical and literary inquiry into Vedic and Buddhist religions attained maturity. His concern to penetrate to the historical foundations of Buddhism and Vedism, which was representative of contemporary trends of German historical scholarship in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, may seem somewhat naive to scholars today. Oldenberg died little more than a year before the first productive season of archaeological investigations in the Indus Valley, work destined to alter decisively many then-prevailing conceptions of the earliest stages of Indian civilization and religion. One can only conjecture how he would have responded to these discoveries.

The invention of an Aryan race in nineteenth century Europe was to have, as we all know, far-reaching consequences on world history. Its application to European societies culminated in the ideology of Nazi Germany. Another sequel was that it became foundational to the interpretation of early Indian history and there have been attempts at a literal application of the theory to Indian society. Some European scholars now describe it as a nineteenth century myth. [1] But some contemporary Indian political ideologies seem determined to renew its life. In this they are assisted by those who still carry the imprint of this nineteenth century theory and treat it as central to the question of Indian identity. With the widespread discussion on 'Aryan origins' in the print media and the controversy over its treatment in school textbooks, it has become the subject of a larger debate in terms of its ideological underpinnings rather than merely the differing readings among archaeologists and historians.

I intend to begin by briefly sketching the emergence of the theory in Europe, in which the search for the Indian past also played a role. I would like to continue with various Indian interpretations of the theory which have been significant to the creation of modern Indian identities and to nationalism. Finally, I would like to review the major archaeological and literary evidence which questions the historical interpretations of the theory and implicitly also its political role. [2]

It was initially both curiosity and the colonial requirement of knowledge about their subject peoples, that led the officers of the East India Company serving in India to explore the history and culture of the colony which they were governing. The time was the late eighteenth century. Not only had the awareness of new worlds entered the consciousness of Europe, but knowledge as an aspect of the Enlightenment was thought to provide access to power. Governing a colony involved familiarity with what had preceded the arrival of the colonial power on the Indian scene. The focus therefore was on languages, law and religion. The belief that history was essential to this knowledge was thwarted by the seeming absence of histories of early India. That the beginnings of Indian history would have to be rediscovered through European methods of historical scholarship, with an emphasis on chronology and sequential narrative, became the challenge.

These early explorations were dominated by the need to construct a chronology for the Indian past. Attempts were made to trace parallels with Biblical theories and chronology. But the exploration with the maximum potential lay in the study of languages and particularly Sanskrit. Similarities between Greek and Latin and Sanskrit, noticed even earlier, were clinched with William Jones' reading of Sandracottos as Candragupta. Two other developments took place. One was the suggestion of a monogenesis or single origin of all related languages, an idea which was extended to the speakers of the languages as well. [3] The second was the emergence of comparative philology, which aroused considerable interest, especially after the availability of Vedic texts in the early nineteenth century. Vedic studies were hospitably received in Europe where there was already both enthusiasm for or criticism of, Indian culture. German romanticism and the writings of Herder and Schlegel suggested that the roots of human history might go back to these early beginnings recorded in Sanskrit texts. [4] James Mill on the other hand, had a different view in his highly influential History of British India, where he described India as backward and stagnant and Hindu civilisation as inimical to progress. [5]

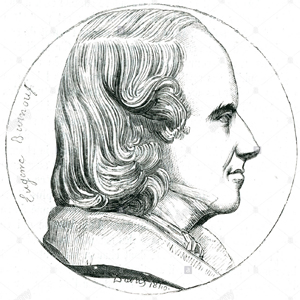

Comparative philologists, such as E. [Eugene] Burnouf and F. [Franz] Bopp were primarily interested in the technicalities of language. Vedic Sanskrit, as the earliest form of Sanskrit, had primacy. Monogenesis was strengthened with the notion of an ancestral language, Indo-Germanic or Indo-European as it came to be called, as also in the origins of some European languages and their speakers being traced back to Iran and India or still further, to a central Asian homeland. Europe was on the edge of an Oriental Renaissance for it was believed that yet another Renaissance might follow, this time from the 'discovery' of the Orient, and thus taking knowledge into yet other directions. [6] The scholars associated with these studies and therefore with interpreting the Indian past, were generally based in Europe and had no direct experience of India.

The latter part of the nineteenth century witnessed discussions on the inter-relatedness of language, culture and race, and the notion of biological race came to the forefront. [7] The experience of imperialism where the European 'races' were viewed as advanced, and those of the colonised, as 'lesser breeds', reinforced these identities, as did social Darwinism.

Prominent among these identities was Aryan, used both for the language and the race, as current in the mid-nineteenth century. [8] Aryan was derived from the Old Iranian arya used in the Zoroastrian text, the Avesta, and was a cognate of the Sanskrit arya. Gobineau, who attempted to identify the races of Europe as Aryan and non-Aryan with an intrusion of the Semitic, associated the Aryans with the sons of Noah but emphasised the superiority of the white race and was fearful about the bastardisation of this race. [9] The study of craniology which became important at this time began to question the wider identity of the Aryan. It was discovered that the speakers of Indo-European languages were represented by diverse skull types. This was in part responsible for a new turn to the theory in the suggestion that the European Aryans were distinct from the Asian Aryans. 10 The former were said to be indigenous to Europe while the latter had their homeland in Asia. If the European Aryans were indigenous to northern Europe then the Nordic blonde was the prototype Aryan. Such theories liberated the origins of European civilisation from being embedded in Biblical history. They also had the approval of rationalist groups opposed to the Church, and supportive of Enlightenment thinking.Our [Theosophical] Society is on the basis of a Brotherhood of Humanity. I might admit that it also is a league of religions against the common enemy -- Christianity.

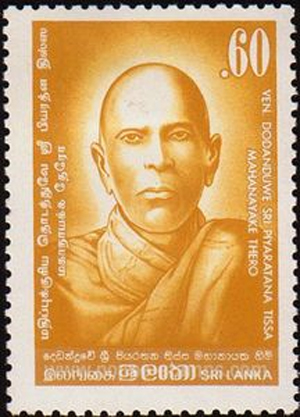

-- Letter to Dodanduwa Sri Piyaratana Tissa Mahanayake Thero, by Henry Steel Olcott, from Theosophists and Buddhists, Excerpt from White Sahibs, Brown Sahibs: Tracking Dharmapala, by Susantha Goonatilake

The application of these ideas to Indian origins was strengthened by Max Mueller's work on Sanskrit and Vedic studies and in particular his editing of the Rigveda during the years from 1849 to 1874. He ascribed the importance of this study to his belief that the Rigveda was the most ancient literature of the world, providing evidence of the roots of Indo-Aryan and the key to Hinduism. Together with the Avesta it formed the earliest stratum of Indo-European.

Max Mueller maintained that there was an original Aryan homeland in central Asia. He postulated a small Aryan clan on a high elevation in central Asia, speaking a language which was not yet Sanskrit or Greek, a kind of proto-language ancestral to later Indo-European languages. From here and over the course of some centuries, it branched off in two directions; one came towards Europe and the other migrated to Iran, eventually splitting again with one segment invading north-western India. [11] The common origin of the Aryans was for him unquestioned. The northern Aryans who are said to have migrated to Europe are described by Max Mueller as active and combative and they developed the idea of a nation, while the southern Aryans who migrated to Iran and to India were passive and meditative, concerned with religion and philosophy. This description is still quoted for the inhabitants of India and has even come to be a cliche in the minds of many.

The Aryans, according to Max Mueller were fair-complexioned Indo-European speakers who conquered the dark-skinned dasas of India. The arya-varna and the dasa-varna of the Rigveda were understood as two conflicting groups differentiated particularly by skin colour, but also by language and religious practice, which doubtless underlined the racial interpretation of the terms. The Aryas developed Vedic Sanskrit as their language. The Dasas were the indigenous people, of Scythian origin, whom he called Turanians. The Aryan and the non-Aryan were segregated through the instituting of caste. The upper castes and particularly the brahmanas of modern times were said to be of Aryan descent and the lower castes and untouchables and tribes were descended from the Dasas. Max Mueller popularised the use of the term Aryan in the Indian context, arguing that it was originally a national name and later came to mean a person of good family. As was common in the nineteenth century, he used a number of words interchangeably such as Hindu and Indian, or race / nation / people / blood / — words whose meanings would today be carefully differentiated. Having posited the idea of a common origin for the languages included as Indo-European and among which was Indo-Aryan, common origin was extended to the speakers of these languages. Aryan therefore, although specifically a label for a language, came to be used for a people and a race as well, the argument being that those who spoke the same language belonged to the same biological race. In a lecture delivered later at Strassburg in 1872, Max Mueller denied any link between language and race. In spite of this, he continued to confuse the two as is evident from his description of Raja Ram Mohan Roy in an Address delivered in 1883.Ram Mohan Roy was an Arya belonging to the south-eastern branch of the Aryan race and he spoke an Aryan language, the Bengali. . . We recognise in Ram Mohan Roy's visit to England the meeting again of the two great branches of the Aryan race, after they had been separated so long that they had lost all recollection of their common origin, common language and common faith. [12]

The sliding from language to race became general to contemporary thinking. An equally erroneous equation was the identification of Dravidian languages with a Dravidian race. [13]

This reconstruction of what was believed to be Aryan history, supercedes the initial Orientalist search for Biblical parallels or connections with early Indian history. There was now a focus on common origins with Europe, untouched by the intervention of the Semitic peoples and languages. As an Aryan text the Rigveda is said to be free from any taint of Semitic contact. Nor do the Puranas which were significant to Orientalist reconstructions of the past, enter Max Mueller's discourse for whom they were not only later but were in comparison, second order knowledge. The Puranas, in their descriptions of the past, do not endorse an arya-dasa separation in a manner which could be interpreted as different races. There was also an exclusion of anything Islamic in Max Mueller's definition of the Indian. He refers to the tyranny of Mohammedan rule in India without explaining why he thought it was so.

The theory of Aryan race became endemic to the reconstruction of Indian history and the reasons for this are varied. The pre-eminence given to the role of the brahmanas in the Orientalist construction of Indology was endorsed by the centrality of the Vedas. The Aryan theory also provided the colonised with status and self-esteem, arguing that they were linguistically and racially of the same stock as the colonisers. However, the separation of the European Aryans from the Asian Aryans was in effect a denial of this status. Such a denial was necessary in the view of those who proposed a radical structuring of colonial society through new legislation and administration, and in accordance with the conversion of the colony into a viable source of revenue. The complexities of caste were simplified in its being explained as racial segregation, demarcating the Aryans from the others.14 And finally, it made Indian origins relevant to the current perceptions dominating European thought and these perceptions were believed to be 'scientific' explanations...

These views coincided with the emergence of nationalism in the late nineteenth century in India, articulated mainly by the middle class, which was drawn from the upper caste and was seeking both legitimacy and an identity from the past. Origins therefore became crucial. To legitimise the status of this middle class, its superior Aryan origins and lineal descent was emphasised. It was assumed that only the upper caste Hindu could claim Aryan ancestry. This effectively excluded not only the lower castes but also the non-Hindus, even those of some social standing. Aryanism therefore became an exclusive status. In the dialogue between the early nationalists and the colonial power, a theory of common origins strengthening a possible link between the colonisers and the Indian elite came in very useful. For early nationalism, Aryan and non-Aryan differentiation was of an ethnic and racial kind, but was also beginning to touch implicitly on class differentiation.

Sympathetic to nationalism in India were the views of the Theosophical Society which changed the theory to suit its own premises. A prominent member of the Society, Col. Olcott [22] maintained that not only were the Aryans (equated with the Hindus) indigenous to India but that they were also the progenitors of European civilisation. Theosophical views emerged out of what was believed to be an aura of oriental religions and particularly Hinduism, as also the supposed dichotomy between the spiritualism of India and the materialism of Europe. The romanticising of India included viewing its civilisation as providing a counter-point to an industrialising Europe obsessed with rationalism, both of which were seen as eroding the European quality of life.

The theosophical reading of the Aryan theory was echoed in the interpretation of the theory by Hindu nationalist opinion. A group of people, close to and involved with the founding of the R.S.S. (Rashtriya Svayamsevaka Sangha) and writing in the early twentieth century, developed the concept of Hindutva or Hinduness and argued that this was essential to the identity of the Indian. [23] Since Hinduness in the past did not have a specific definition, the essentials of a Hindu identity had to be formulated. The argument ran that the original Hindus were the Aryans, a distinctive people indigenous to India. Caste Hindus or Hindu Aryas are their descendents. There was no Aryan invasion since the Aryans were indigenous to India and therefore no confrontation among the people of India. The Aryans spoke Sanskrit and were responsible for the spread of Aryan civilisation from India to the west. Confrontations came with the arrival of foreigners such as the Muslims, the Christians and more recently, the Communists. These groups are alien because India is neither the pitribhumi — the land of their birth — the assumption being that all Muslims and Christians are from outside India, nor the punyabhumi — their holy land. Hindu Aryas have had to constantly battle against these foreigners. Influenced by European theories of race of the 1920's and 1930's, parallels were drawn between the European differentiation of Aryans and Semites with the Indian differentiation of Hindus and Muslims. Justifying the treatment of the Jews in Germany, the threat of the same fate was held out to the Muslims in India.

-- The Theory of Aryan Race and India: History and Politics, by Romila Thapar

It seems altogether certain, however, that he would have dealt with them in that same clear-sighted, unsentimental, and critical fashion that characterized all his scholarly work. His persisting efforts to unveil the earliest stages of India's religious thought and history, his rigorous philological method, and the degree to which he integrated insights from other disciplines, stand as important monuments that will continue to inform and guide research.

Bibliography

Unhappily, the direct impact of Oldenberg's scholarship on investigations in the English-speaking world has been limited by the paucity of translations. English editions of Oldenberg's works include William Hoey's translation of Buddha: Sein Leben, seine Lehre, seine Gemeinde as The Buddha: His Life, His Doctrine, His Order (London, 1882), which should be consulted alongside the thirteenth German edition, annotated by Helmuth von Glasenapp, as well as the following books, each of which is accompanied by a valuable introduction: The Dīpavaṃsa (London, 1879); Vinaya Texts (Oxford, 1881–1885); The Gṛhyasūtras: Rules of Vedic Domestic Ceremonies, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1886–1892); and part 2 ("Hymns to Agni") of Vedic Hymns (Oxford, 1897). Also, three of his general essays have been published together as Ancient India (Chicago, 1898). Of inestimable value is Klaus Janert's careful two-volume edition of Oldenberg's Kleine Schriften (Wiesbaden, 1967), which includes not only full texts of more than one hundred articles but also an exhaustive bibliography.

************************************

Translator's Preface, Excerpt from Buddha: His Life, His Doctrine, His Order

by Dr. Hermann Oldenberg, Professor at the University of Berlin, Editor of the Vinaya Pitakam and the Dipavamsa in Pali

Translator's Preface

This book is a translation of a German work, Buddha, Sein Leben, seine Lehre, seine Gemeinde, by Professor Hermann Oldenberg, of Berlin, editor of the "Pali Texts of the Vinaya Pitakam and the Dipavamsa." The original has attracted the attention of European scholars, and the name of Dr. Oldenberg is a sufficient guarantee of the value of its contents. A review of the original doctrines of Buddhism, coming from the pen of the eminent German scholar, the coadjutor of Mr. Rhys Davids in the translation of the Pali scriptures for Professor Max Muller's "Sacred Books of the East," and the editor of many Pali texts, must be welcome as an addition to the aids which we possess to the study of Buddhism. Dr. Oldenberg has in the work now translated successfully demolished the sceptical theory of a solar Buddha, put forward by M. [Emile Charles Marie] Senart. He has sifted the legendary elements of Buddhist tradition, and has given the reliable residuum of facts concerning Buddha s life: he has examined the original teaching of Buddha, shown that the cardinal tenets of the pessimism which he preached are "the truth of suffering and the truth of the deliverance from suffering:" he has expounded the ontology of Buddhism and placed the Nirvana in a true light. To do this he has gone to the roots of Buddhism in pre-Buddhist Brahmanism: and he has given Orientalists the original authorities for his views of Buddhist dogmatics in Excursus at the end of his work.

To thoughtful men who evince an interest in the comparative study of religious beliefs, Buddhism, as the highest effort of pure intellect to solve the problem of being, is attractive. It is not less so to the metaphysician and sociologist who study the philosophy of the modern German pessimistic school and observe its social tendencies. To them Dr. Oldenberg s work will be as valuable as it is to the Orientalist.

My aim in this translation has been to reproduce the thought of the original in clear English. If I have done this, I have succeeded. Dr. Oldenberg has kindly perused my manuscript before going to press: and in a few passages of the English I have made slight alterations, additions, or omissions, as compared with the German original, at his request.1

I have to thank Dr. [Reinhold] Rost, the Librarian of the India Office, at whose suggestion I undertook this work, for his kindness and courtesy in facilitating some references which I found it necessary to make to the India Office Library.

Rhys Davids was home schooled by her father and then attended University College, London studying philosophy, psychology, and economics (PPE). She completed her BA in 1886 and an MA in philosophy in 1889. During her time at University College, she won both the John Stuart Mill Scholarship and the Joseph Hume Scholarship. It was her psychology tutor George Croom Robertson who "sent her to Professor Rhys Davids",[5] her future husband, to further her interest in Indian philosophy. She also studied Sanskrit and Indian Philosophy with Reinhold Rost.Reinhold Rost (1822–1896) was a German orientalist, who worked for most of his life at St Augustine's Missionary College, Canterbury in EnglandSt Augustine’s College in Canterbury, Kent, United Kingdom, was located within the precincts of St Augustine's Abbey about 0.2 miles (335 metres) ESE of Canterbury Cathedral. It served first as a missionary college of the Church of England (1848-1947) and later as the Central College of the Anglican Communion (1952-1967).

The mid-19th century witnessed a "mass-migration" from England to its colonies. In response, the Church of England sent clergy, but the demand for them to serve overseas exceeded supply. Colonial bishoprics were established, but the bishops were without clergy. The training of missionary clergy for the colonies was “notoriously difficult” because they were required to have not only “piety and desire”, they were required to have an education “equivalent to that of a university degree”. The founding of the missionary college of St Augustine’s provided a solution to this problem.

The Revd Edward Coleridge, a teacher at Eton College, envisioned establishing a college for the purpose of training clergy for service in the colonies: both as ministers for the colonists and as missionaries to the native populations...

-- St Augustine's College, Canterbury, by Wikipedia

and as head librarian at the India Office Library, London.

He was the son of Christian Friedrich Rost, a Lutheran minister, and his wife Eleonore Glasewald, born at Eisenberg in Saxen-Altenburg on 2 February 1822. He was educated at the Eisenberg gymnasium school, and, after studying under Johann Gustav Stickel and Johann Gildemeister, graduated Ph.D. at the University of Jena in 1847. In the same year he came to England, to act as a teacher in German at the King's School, Canterbury. After four years, on 7 February 1851, he was appointed oriental lecturer at St. Augustine's Missionary College, Canterbury, founded to educate young men for mission work. This post he held for the rest of his life.

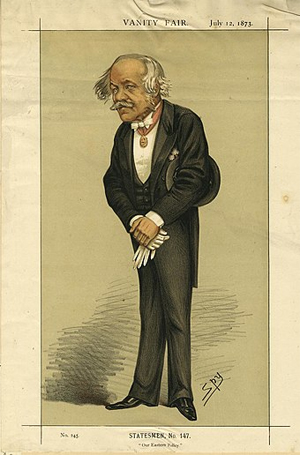

In London, Rost met Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, and was elected, in December 1863, secretary to the Royal Asiatic Society, a post he held for six years.Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, GCB FRS (5 April 1810 – 5 March 1895) was a British East India Company army officer, politician and Orientalist, sometimes described as the Father of Assyriology. His son, also Henry, was to become a senior commander in the British Army during World War I...

Rawlinson was appointed political agent at Kandahar in 1840. In that capacity he served for three years, his political labours being considered as meritorious as was his gallantry during various engagements in the course of the Afghan War; for these he was rewarded by the distinction of Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1844.

Serendipitously, he became known personally to the governor-general, which resulted in his appointment as political agent in Ottoman Arabia. Thus he settled in Baghdad, where he devoted himself to cuneiform studies. He was now able, with considerable difficulty and at no small personal risk, to make a complete transcript of the Behistun inscription, which he was also successful in deciphering and interpreting. Having collected a large amount of invaluable information on this and kindred topics, in addition to much geographical knowledge gained in the prosecution of various explorations (including visits with Sir Austen Henry Layard to the ruins of Nineveh), he returned to England on leave of absence in 1849.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in February 1850 on account of being "The Discoverer of the key to the Ancient Persian, Babylonian, and Assyrian Inscriptions in the Cuneiform character. The Author of various papers on the philology, antiquities, and Geography of Mesopotamia and Central Asia. Eminent as a Scholar".

Rawlinson remained at home for two years, published in 1851 his memoir on the Behistun inscription, and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He disposed of his valuable collection of Babylonian, Sabaean, and Sassanian antiquities to the trustees of the British Museum, who also made him a considerable grant to enable him to carry on the Assyrian and Babylonian excavations initiated by Layard. During 1851 he returned to Baghdad. The excavations were performed by his direction with valuable results, among the most important being the discovery of material that contributed greatly to the final decipherment and interpretation of the cuneiform character. Rawlinson's greatest contribution to the deciphering of the cuneiform scripts was the discovery that individual signs had multiple readings depending on their context. While at the British Museum, Rawlinson worked with the younger George Smith.

An equestrian accident in 1855 hastened his determination to return to England, and in that year he resigned his post in the East India Company. On his return to England the distinction of Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath was conferred upon him, and he was appointed a crown director of the East India Company.

The remaining forty years of his life were full of activity—political, diplomatic, and scientific—and were spent mainly in London. In 1858 he was appointed a member of the first India Council, but resigned during 1859 on being sent to Persia as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary. The latter post he held for only a year, owing to his dissatisfaction with circumstances concerning his official position there. Previously he had sat in Parliament as Member of Parliament (MP) for Reigate from February to September 1858; he was again MP for Frome, from 1865 to 1868. He was appointed to the Council of India again in 1868, and continued to serve upon it until his death. He was a strong advocate of the forward policy in Afghanistan, and counselled the retention of Kandahar.

Rawlinson was one of the most important figures arguing that Britain must check Russian ambitions in South Asia. He was a strong advocate of the forward policy in Afghanistan, and counselled the retention of Kandahar. He argued that Tsarist Russia would attack and absorb Khokand, Bokhara and Khiva (which they did – they are now parts of Uzbekistan) and warned they would invade Persia (present-day Iran) and Afghanistan as springboards to British India.

He was a trustee of the British Museum from 1876 till his death. He was created Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1889, and a Baronet in 1891; was president of the Royal Geographical Society from 1874 to 1875, and of the Royal Asiatic Society from 1869 to 1871 and 1878 to 1881; and received honorary degrees at Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh.

-- Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, by Wikipedia

Through Rawlinson he became on 1 July 1869 librarian at the India Office, on the retirement of FitzEdward Hall, and imposed order on its manuscripts.Fitzedward Hall (March 21, 1825 - February 1, 1901) was an American Orientalist, and philologist. He was the first American to edit a Sanskrit text, and was an early collaborator in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) project...

He graduated with the degree of civil engineer from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute at Troy in 1842, and entered Harvard in the class of 1846. His Harvard classmates included Charles Eliot Norton, who later visited him in India in 1849, and Francis James Child. Just before his class graduated but after completing the work for his degree he abruptly left college and took ship out of Boston to India, allegedly in search of a runaway brother. His ship foundered and was wrecked on its approach to the harbor of Calcutta, where he found himself stranded. Although it was not his intention, he was never to return to the United States. At this time, he began his study of Indian languages, and in January 1850 he was appointed tutor in the Government Sanskrit College at Benares. In 1852, he became the first American to edit a Sanskrit text, namely the Vedanta treatises Ātmabodha and Tattvabodha. In 1853, he became professor of Sanskrit and English at the Government Sanskrit College; and in 1855 was appointed to the post of Inspector of Public Instruction in Ajmere-Merwara and in 1856 in the Central Provinces.

In 1857, Hall was caught up in the Sepoy Mutiny. The Manchester Guardian later gave this account:[2] "When the Mutiny broke out he was Inspector of Public Instruction for Central India, and was beleaguered in the Saugor Fort. He had become an expert tiger shooter, and turned this proficiency to account during the siege of the fort, and afterwards as a volunteer in the struggle for the re-establishment of the British power in India."

In 1859, he published at Calcutta his discursive and informative A Contribution Towards an Index to the Bibliography of the Indian Philosophical Systems, based on the holdings of the Benares College and his own collection of Sanskrit manuscripts, as well as numerous other private collections he had examined. In the introduction, he regrets that this production was in press in Allahabad and would have been put before the public in 1857, "had it not been impressed to feed a rebel bonfire."

He settled in England and in 1862 received the appointment to the Chair of Sanskrit, Hindustani and Indian jurisprudence in King's College London, and to the librarianship of the India Office. An unsuccessful attempt was made by his friends to lure him back to Harvard by endowing a Chair of Sanskrit for him there, but this project came to nothing. His collection of a thousand Oriental manuscripts he gave to Harvard...

In 1869 Hall was dismissed by the India Office, which accused him (by his own account) of being a drunk and a foreign spy, and expelled from the Philological Society after a series of acrimonious exchanges in the letters columns of various journals.

-- Fitzedward Hall, by Wikipedia

He secured for students free admission to the library. He retired in 1893 after 24 years of service at the age of 70. His successor as head librarian of the India Office Library became the Orientalist and Sanskritist Charles Henry Tawney (1837-1922).

Rost gained many distinctions and awards. He was created Hon. LL.D. of Edinburgh in 1877, and a Companion of the Indian Empire in 1888. He died at Canterbury on 7 February 1896.[1]

-- Reinhold Rost, by Wikiedia

-- Caroline Rhys Davids, by Wikipedia

W. HOEY.

BELFAST, October 21, 1882.