by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

T. W. Rhys Davids’s interest in Pāli began while he was serving in the Ceylon Civil Service (1864–72). His association with Buddhism at this time was incidental—to learn Pāli he had to study with a bhikkhu. His first translation, typical of the historical bias of his time, was in numismatics and epigraphy, an outcome of his posting to the archaeologically rich area of Anuradhapura, and led in 1877 to his Ancient Coins and Measures of Ceylon, which contained the first attempt to date the death of the Buddha.9 He did not write on Buddhism until after his return to Britain, and a modest comment on how little he knew about Buddhism at that time, which is quoted by Ananda Wickremaratne, suggests that he was invited to do so because of popular interest in Buddhism.10 His first book, the highly influential Buddhism: A Sketch of the Life and Teachings of Gautama, the Buddha (1878), was compiled from the material then available in translation.11 This book established his reputation as a Buddhist scholar. It was followed by his translations Buddhist Birth Stories and Buddhist Suttas, both published in 1880.12 During the influential Hibbert Lectures of 1881, he announced the founding of the Pāli Text Society, confidently predicting the publication of the whole of the texts of the Sutta and Abhidhamma Pitakas in “no very distant period.”13 The inaugural committee of management included, among others willing to undertake translation, the Pāli scholars Victor Fausboll, Hermann Oldenberg, and Emile Senart. There was clearly a growing interest and activity in Pāli translation by this time. The formation of the Pāli Text Society institutionalized the study of Buddhism and the interpretation of it, which had begun much earlier. It is necessary therefore to look briefly at the earlier period.

-- Defining Modern Buddhism: Mr. and Mrs. Rhys Davids and the Pali Text Society, by Judith Snodgrass

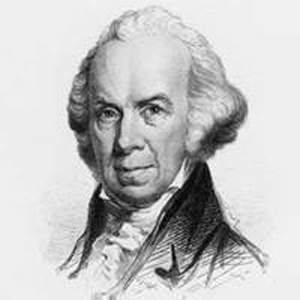

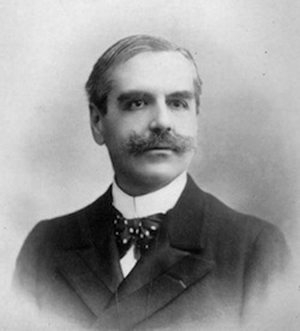

Émile Senart

Born: Émile Charles Marie Senart, 26 March 1847, Reims

Died: 21 February 1928 (aged 80), Paris

Occupation: Indologist

Émile Charles Marie Senart (26 March 1847 – 21 February 1928) was a French Indologist.

Besides numerous epigraphic works, we owe him several translations in French of Buddhist and Hindu texts, including several Upaniṣad.

He was Paul Pelliot's professor at the Collège de France.

He was elected a member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres in 1882, president of the Société asiatique [Asiatic Society] from 1908 to 1928 ...

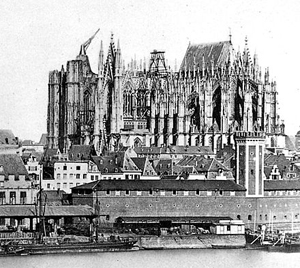

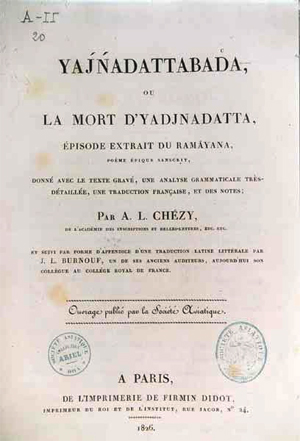

The Société Asiatique (Asiatic Society) is a French learned society dedicated to the study of Asia. It was founded in 1822 with the mission of developing and diffusing knowledge of Asia. Its boundaries of geographic interest are broad, ranging from the Maghreb to the Far East. The society publishes the Journal asiatique [1822-1936]. At present the society has about 700 members in France and abroad; its library contains over 90,000 volumes.

The establishment of the society was confirmed by royal ordinance on April 15, 1829. Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy was the first president.

Notable people

• Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat

• Jacques Bacot

• Jean Berlie

• Eugène Burnouf

• Jean-François Champollion

• Henri Cordier

• Jean-Baptiste Benoît Eyriès

• Julius Klaproth

• Louis Finot

• Jean Leclant

• Sylvain Lévi

• Abdallah Marrash

• Gaston Maspero

• Paul Pelliot

• Joseph Toussaint Reinaud

• Ernest Renan

• Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin

• Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy

• İbrahim Şinasi

• Charles Virolleaud

List of the presidents of the Société

• 1822–1829: Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy

• 1829–1832: Jean-Pierre Abel Rémusat

• 1832–1834: Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy

• 1834–1847: Amédée Jaubert

• 1847–1867: Joseph Toussaint Reinaud

• 1867–1876: Julius von Mohl

• 1876–1878: Joseph Héliodore Garcin de Tassy

• 1878–1884: Adolphe Régnier

• 1884–1892: Ernest Renan

• 1892–1908: Barbier de Meynard

• 1908–1928: Émile Senart

• 1928–1935: Sylvain Lévi

• 1935–1945: Paul Pelliot

• 1946–1951: Jacques Bacot

• 1952–1964: Charles Virolleaud

• 1964–1969: George Coedès

• 1969–1974: René Labat

• 1974–1986: Claude Cahen

• 1987–1996: André Caquot

• 1996–2002: Daniel Gimaret

• 2002–present: Jean-Pierre Mahé

-- Société Asiatique [Asiatic Society], by Wikipedia

and founder of the "Association française des amis de l'Orient" in 1920.

Selected works

• 1875: Essai sur la légende du Bouddha - Paris.

• Les Inscriptions de Piyadasi - Paris

• 1881: Les Inscriptions de Piyadasi / 1 / Les quatorze édits.

• 1886: Les Inscriptions de Piyadasi / 2 / L.édits détachés. L'auteur et la langue des édits.

• 1882–1897: Le Mahāvastu: Sanskrit text. Published for the first time and accompanied by introductions and commentary by E. Sénart. - Paris : Imprimerie Nationale, 1882-1897, Volume 1/ 1882, Volume 2/ 1890, Volume 3/ 1897

• 1889: Gustave Garrez

• 1896: Les Castes dans l'Inde, les faits et le système - Paris (Caste in India. Translated by E. Denison Ross. London 1930)

• 1901: Text of Inscriptions discovered at the Niya Site, 1901 / Transcr. and edited by A. M. Boyer, E. J. Rapson and E. Senart. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1920 (Kharosthi Inscriptions discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in Chinese Turkestan ; 1)

• 1907: Origines Bouddhiques

• 1927: Text of Inscriptions discovered at the Niya, Endere, and Lou-lan Sites, 1906-7 / Auguste M. Boyer; Edward James Rapson; Émile Charles Marie Senart. - Oxford.

• 1930: Chāndogya Upaniṣad Translated and annotated by Émile Sénart, Société d'édition: Les Belles Lettres, Paris.

Sources

• This article contains text from a document on the La vie rémoise site.

External links

• Émile Sénard on Wikisource

• SENART Émile, Charles, Marie on Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

• Obituary on Persée

********************************

Obituary Notices: Emile Charles Marie Senart

by F.W. Thomas

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

No. 3, pp. 751-760

July 1928

The greatest part of M. Senart’s productivity as a scholar was concerned with Buddhism. In 1871, at the age of 24, he made his debut, in the Journal Asiatique (vi. xvii., pp. 193-540), by a publication of Kaccayana’s Pali Grammar, sutras and commentary, a work of great difficulty; the translation and notes betrayed no signs of immaturity and manifested a familiarity with the Sanskrit grammarians, whose model Kaccayana had followed. Next, published likewise as a series of articles in the Journal Asiatique, 1873-5, and issued as a volume in 1875, came the celebrated Essai sur la legend du Buddha, a book which has always been provocative to the more literal Buddhologists. No one can doubt that the story of Buddha, largely miraculous, is also in part mythological. The speciality of M. Senart’s theory was that the person of Buddha had absorbed not merely isolated mythological factors, but a fairly compact body of conceptions, originally solar. The case would be parallel to a well-known illustration accompanying one of Thackeray’s essays and showing three designs: (1) Rex (an imposing royal costume, standing by itself), (2) Ludovicus (a mere man), and (3) Ludovicus Rex, the combined awe-inspiring figure. It seems rather clear that the idea of the cakravartin was pre-Buddhistic and ultimately solar: the events preceding the abandonment of home are at least highly poetical, the detailed incidents of the illumination and the defeat of Mara are surely mythology, and, even if the Bodhi-tree was an actuality, it was a conventional adjunct of ascetics, and, as such, symbolical too – though the symbolism need not have been solar. M. Senart may not have gone too far in suggesting a doubt whether Maya is a fictitious name for Buddha’s mother or even that of Suddhodana for his father; but clearly it was imprudent to doubt the existence of Kapilavastu. How much can be retained of the theory of the Visnuite or Krsnaite character of the legend it would not be easy to say. But, in fact, the legendary part of the Buddha story would hardly now be seriously considered by scholars, who are more concerned to discover what views were propounded by the person who figures in the Pali dialogues and why both he and Mahavira founded not schools, but sects.

In 1877, M. Senart published a short article, entitled Sur quelques termes buddhiques, wherein he took note of certain forms of words occurring in the Buddhist texts, such as upadisesa, which seemed to point to an earlier canonic dialect more developed (plus altere, plus prakritisant) than appears in their surroundings. His preoccupation with the dialects was also evidenced by a long and suggestive review of Cunningham, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, 1877. The articles containing his own edition of the Inscriptions de Piyadasi began to appear in 1880.1 The completed work (1881) was translated by Sir George Grierson in the Indian Antiquary (xviii, 1889-xxi, 1892). M. Senart was able in some instances to make use of new facsimiles furnished by Dr. Burgess. But the great advance in the interpretation was due mainly to his own insight and his familiarity with the Pali language and literature. The concluding chapters are devoted to a study of the date and chronology of the inscriptions and the general questions of Buddhist chronology so far as connected therewith; the author of the inscriptions, his faith and his measures; the language and the several dialects, whereof full grammatical sketches are given; the linguistic chronology of India and the interrelations between Sanskrit, Mixed Sanskrit, the Prakrits, and Pali. Almost all the conclusions at which M. Senart arrived (including his acceptance of the date A.D. 319 for the commencement of the Gupta era) still hold good. But there is one great matter which seems in his argument to retain some of its previous obscurity. He holds that the alphabets show by their inadequacy that they could not have been used for writing Sanskrit (or, we may add, Pali). The first Sanskrit to be written was the Mixed Sanskrit of certain inscriptions, which had been known as the Gatha dialect and for which M. Senart had himself previously proposed the name Buddhist Sanskrit. This ceased to exist at the moment when the philological exactitude of the old Brahman schools extended its influence. The Prakrits and the Pali also assumed a definite form when controlled by a similar influence. The process may have begun about A.D. 100 and have been completed before the Gupta period. The matter is certainly puzzling, and it is clear that the Asokan alphabets must have been developed in certain points before they could be fitted for the writing of Sanskrit. But the inference that at the time there was no written Sanskrit, and in fact no worldly Sanskrit at all, seems inadequately grounded. The influence of the learned language upon the popular speech did not commence with Panini: it must have begun from the moment when the vernacular began to diverge from the language of the texts (Brahmanas, Upanisads, and so forth). What Panini discriminated was the correct language of the sistas, the scholars. We know from the early references in the Chandogya-Upanisad and elsewhere that there were whole classes of writings of a worldly character, and these must have been composed in fairly popular speech. Thus in principle the Mixed Sanskrit must go back many centuries B.C., and we cannot doubt that stages of it existed at the time of Buddha and in that of Asoka. The character of the Buddhist Sanskrit was, of course, fully recognized by M. Senart, and his divergence from the view of Burnouf that it was a language of persons who, with inadequate competence, were trying to write the literary language is a little hard to seize. The Mixed Sanskrit is Sanskrit with faults, a variety of that “bad Sanskrit” which we find in Vedic Parisistas, manuals of crafts, arts, etc. Its only excuse for existence was its actual currency, and it was no doubt the spread of grammatical training that ultimately expelled it from all higher literature. To this extent we cannot but subscribe to M. Senart’s view. But, then, for the Mixed Sanskrit the Asokan alphabets are no less inadequate than for the scholarly form; so that we should have to deny that the Mixed Sanskrit itself was written prior to the use of double consonants, differentiation of the sibilants, the nasals and so forth. We must, it seems, stop short of this and hold (1) that writing was first employed in connection with popular speech, for business purposes, and so forth, (2) that the Sanskrit, like the Mixed Sanskrit, may at first have made shift with the imperfect alphabets as used in the Asoka inscriptions (possibly writing double consonants with viramas and so forth), (3) that the inscriptions themselves, being written in merely popular and official dialects, may have been content with alphabetic practice less developed than that which at the time was in actual use for literary purposes – this last proposition is in fact maintained by Buhler. M. Senart’s discrimination of the different dialects represented in the Edicts, his recognition of the Magadhi as official over an area wider than its currency and of its particular intrusions in the texts of the other dialects have been generally confirmed; and his detailed accounts of the features of the several dialects have been merely amplified in later works.

M. Senart’s study of the early inscriptions in the Brahmi and Kharosthi alphabets continued throughout his life as a scholar. New materials and new discoveries were regularly referred to him, and they gave occasion to a long series of articles, for the most part published under the running title Notes de’Epigraphie Indienne,2 always characterized by the most scrupulous examination of the copies and the most penetrating explanation of the texts. His editions of the Karle and Nasik inscriptions (Epigraphia Indica, vol. vii., pp. 47-74; viii, pp. 59-96) brought those texts up to the level of modern scholarship. When the time came for a republication of volume I of the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, his preoccupations did not allow him to undertake the task, which was discharged in a thorough manner by that very sound, careful and fair-minded scholar, Professor Ernst Hultzsch. The last articles by M. Senart on these subjects were his discussion (1916) of the new Asoka edict found at Maski in Hyderabad and – in collaboration with the Abbe Boyer and Professor Rapson – an examination (1918) of a poem inscribed on a Kharosthi tablet from Chinese Turkestan.

We have still, however, to take account of an analogous task of great difficulty, wherein M. Senart collaborated with the same two scholars. The materials consisted of documents, chilefly wooden tablets, discovered by Sir A. Stein in the course of his three expeditions to Chinese Turkestan. The general features of the script and language, as well as some tentative transliterations and translations, were the subject of a communication by Professor Rapson to the Algiers Congress of 1905. But the developed form of the Kharosthi alphabet, including unprecedented combinations of signs, and the mixed character of the vocabulary, which comprises a large number of local proper names and titular designations, entailed a long period of joint manipulation: two fascicule, containing the bulk of the material, were published, under the title Kharosthi Inscriptions, in 1920 and 1927.

The Mahavastu is a Sanskrit Buddhist text, which with its apparatus criticus fills in M. Senart’s edition more than 1300 pages octavo. It is a work of great importance, belonging to the Vinaya of one of the old Buddhist sects, that of the Mahasanghikas. It is a mine of old Buddhist story, observation, reflections, and wit in unlaboured prose and flowing verse: a book which in another literature might be made a life’s study. Unfortunately, it is but a drop in the ocean of Buddhist literature, which we must somehow encompass as a whole if we are not to be engulfed in it. Still more unfortunately, perhaps, it is written in the Mixed Sanskrit, a text presenting at every step irregularities, and even regularities, which may have been imported into it at any stage in its long history. The MSS., of modern date and all from Nepal, have by their discrepancy involved the editor in an enormous labour of collation. If we had copies of older date or of different provenance (say from Central Asia), we should be confronted (as many analogies show) with divergences far more numerous and in many cases on a much larger scale. A definitive text is hardly to be hoped for. The difficulty, however, is in the main a matter only of grammar or language. M. Senart has given us an important canonical text of one of the most influential early sects. Its further study cannot fail to yield continual fruit, and M. Senart’s closely printed commentary of about 400 pages is itself a mine of new and valuable observations upon textual and linguistic matters and upon Buddhist thought and terminology. Still a different dialect appears in the MS. Dutreuil du Rhins, the Kharosthi Dhammapada, concerning which M. Senart read a paper before the Paris Congress of 1897, and which he edited in the Journal Asiatique.3 Among the papers of the ill-fated traveler some birch-bark fragments were noted by M. Sylvain Levi as inscribed in Kharosthi characters. The fragments were for the most part small, in many cases minute; but M. Senart had no difficulty in recognizing a version of the celebrated collection of moral and religious verses known in Pali under the title Dhammapada. The formidable task of decipherment was thus lightened, and M. Senart was able to find Pali equivalents for most of the verses and fragments. It was unfortunate that another part of the same MS. (the Ptrovsky fragments), which had found its way to St. Petersburg, was not fully available for incorporation. The MS. did not originate in Chinese Turkestan: it had been brought from noth-western India, and it furnished a new early Prakrit dialect, which has yet to be fully explored.

There remains for commemoration only one extensive work by M. Senart. This is his monograph on caste (Les Castes dans l’Inde, 1895, reprinted without change in 1927), a subject in regard to which the examination of prior views is almost more onerous than the direct study of the facts. M. Senart’s three chapters are devoted respectively to the present, the past, and the origins, including a criticism of the traditional Brahmanic theory and the conclusions of Nesfield, Ibbetson, and Risley. The main originalities of his own view are (1) the distinction between the original classes, varna, of Brahman, Ksatriya, Vaisya and Sudra, at first two “colours”, varna, namely Aryan and Sudra, and the specific endo-exogamic groups properly denoted by the word jati “caste”, (2) the tracing of the latter organizations to an Aryan source in a gentile constitution of society such as existed in early Greece and Rome. It must be admitted that for gentes in the required sense we do not find much evidence in early India (that is by no means conclusive) and that among the castes mentioned by Manu and other ancient writers (we need not take into account the castes of modern times, after a development of about 2,500 years) we find designations professional, genealogical, tribal, and local, but hardly any of a gentilician import. Also we ought to be able to point to Brahman and Ksatriya gentes: can this be done? Yet M. Senart’s view does account for two main features of caste, namely the endogamic principles and the rules as to common meals. It remains possible that a gentilician constitution of society did leave these features as a legacy to new divisions of very various origins, developing in the complex Indian people.

Besides the works which we have cited we owe to M. Senart a number of studies of less extent. Such are his striking little work on Buddhism and Yoga, his papers on the Abhisambuddha-gathas of the Pali Jataka, on the Vajrapani in early Buddhist art, on Rajas and the theory of the three Gunas in the Samkhya philosophy. In 1922 he published an elegant translation of the Bhagavad-gita. All his writings are distinguished by a refined linguistic sense and a clear unbiased judgment. There is also nothing second-hand or compilatory in his work; on the contrary, his tendency was always towards new and vital conceptions. Considering the combined brilliance and solidity of his work, it cannot be said that in the qualities of a scholar he was surpassed by an Indianist of the latter half of the nineteenth century.

It is well known that M. Senart possessed advantages of fortune which might have proved an obstacle to a strictly scholarly career. Fortunately science and letters can point to not a few instances of men of means who were not merely thinkers or amateurs, but specialist investigators whose work would not have been modified by being professional. M. Senart was always counted among the Indianist circle of the University of Paris, and not only of the Societe Asiatique (Asia Society), in which he was successively member of Council (1872), Vice-President (1890), and President (1908). After the death of M. Barth, to whom in 1914[4] he paid a touching tribute, he was, so to speak, the father of the Paris Indianists. In the Academie des Inscriptions he was the outstanding representative of oriental studies. In such matters as the foundation of the Ecole Francaise d’Extreme-Orient, the Pelliot mission to Central Asia, the Commission Archeologique of the Academy his was usually the directing influence. When the time came for celebrating the centenary of the Societe Asiatique (Asia Society) the full burden of organization and leadership in the splendid succession of ceremonies and festivities recorded in the published record was unflinchingly borne by him. Nor could anything surpass the patience, the courtesy, and the distinguished eloquence and dignity with which at the age of 75 he carried out the whole programme.

From the time of the Paris Congress of 1897, M. Senart was regarded outside France as the leading French orientalist. He was a prominent figure in the gatherings at Rome (1899) and Algiers (1905). He was a member of the permanent international committee, and he also represented the Institute at the international conferences of Academies. In 1917, in order to meet the situation created by the war, and also in view of certain features of the pre-war Congresses, he made formal proposals, on behalf of the Societe Asiatique (Asia Society), providing for mutual privileges, annual gatherings, and joint enterprises. The agreement, to which also the American Oriental Society, the Senola Orientale of the University of Rome, and the Asiatic Society of Japan became parties, is fully recorded in this Journal (1918, pp. 186-97). The first Joint Session was held in London on September 3-6, 1919, and the proceedings are reported in the Journal for 1920, pp. 123-62. There were further meetings at Paris in 1920 and at Brussels in 1921. From the gathering in 1919 four new Orientalist societies directly or indirectly originated, namely in Belgium, Holland, Norway, and Sweden, of which the second, the Oostersch Genootschap in Nederland, has since held annual assemblies of a partly international character. In 1923 the centenary of the Royal Asiatic Society was honoured by M. Senart’s presence as a representative of France. When in 1926 the question of resuming the old series of international gatherings assumed a practicable aspect, M. Senart and his colleagues of the Societe Asiatique (Asia Society) were consenting parties in the negociations and approved the outcome. Shortly afterwards, in march, 1927, M. Senart’s eightieth birthday was made an occasion for messages of congratulation from friends and colleagues both in France and abroad. A critical illness prevented any formal presentation; but the messages did not fail to receive an individual and gracious acknowledgment. Ever scrupulous in the minor offices of social life, a punctual correspondent, a delightful host, and a loyal friend, he realized an ideal of urbane unselfishness, in which only the winning exterior disguised a renunciatory quality. His increasing frailty was naturally as perceptible to himself as to others; but he anticipated its denouement, which took place on February 21 of the present year, without either satisfaction or refret.

He was born at Rheims on March 26, 1847. His relations with the Societe Asiatique (Asia Society] have already been particularized. In 1882 he was elected a member of the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. He was also at various times chosen as a member of the Academies of Belgium, Great Britain, Holland, Italy, and Russia, of Berlin, Gottingen, and Munich, and an Honorary Member of numerous societies. In this country the Royal Asiatic Society paid him that tribute in 1892, and the India Society in 1922 elected him a Vice-President; in 1923 he received the Honorary Doctorate of the University of Oxford. The death of his wife evoked many expressions of sympathy from orientalists who had enjoyed her hospitality at Paris in 1897; it left M. Senart without descendants.’

_______________

Notes

1. Journal Asiatique, VII, XV, pp. 287-347-VIII, viii, pp. 384-478.

2. Journal Asiatique, VIII, ix (1888), pp. 498-504; xi (1888), pp. 504-33; xii (1888), pp. 311-30; xiii (1889), pp. 364-75; xv (1890), pp. 113-63; xix (1892), pp. 472-98; ix, iv (1894), pp. 332053, 504-78; vii (1906), pp. 132-6; xiii (1899), pp. 526-37; xv (1900), pp. 343-60; x, vii, pp. 132-6; xi, iv (1914), pp. 569-85; vii (1916), pp. 425-42; JRAS, 1900, pp. 335-41.

3. IX, xii (1898), pp. 192-308.

4. On the occasion of the presentation recorded in the then collected edition of M. Barth’s writings, pp. vii-xii.