Dayananda Saraswati

by New World Encyclopedia

Accessed: 3/1/21

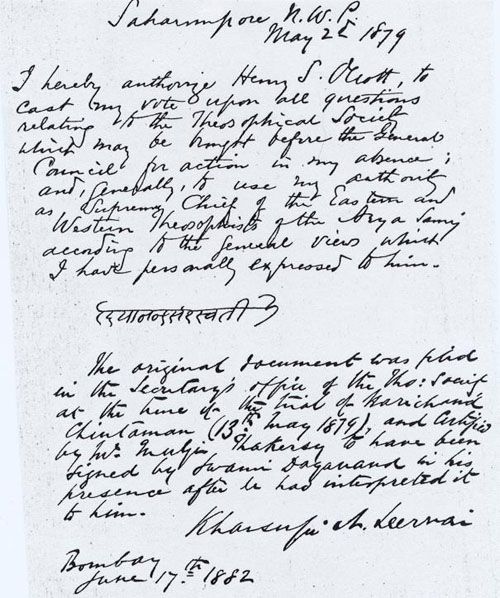

1879, Excerpt from Masters and Men: The Human Story in the Mahatma Letters (a fictionalized account)

by Virginia Hanson

The Theosophical Publishing House

Madras, India

c 1980 The Theosophical Publishing House

Most of the Letters are over the signature of the Mahatma Koot Hoomi, usually signed simply "K.H." A Kashmiri Brahmin by birth, at the time of the correspondence he was a Buddhist. Koot Hoomi is a mystical name which he instructed H.P.B. to use in connection with his correspondence with Mr. Sinnett. It is possible that his real name was Nisi Kanta Chattopadhyaya, as that seems to have been the name by which he was known when he was attending at least one European University. He was fluent in both English and French and was sometimes affectionally spoken of by the Mahatma Morya as "my Frenchified K.H."

At one time, under special circumstances, the Mahatma Morya took over the correspondence temporarily. He too used only his initial as a signature. "He was a Rajput by birth," said H.P.B., "One of the warrior race of the Indian desert, the finest and handsomest nation in the world." He was "a giant, six feet eight, and splendidly built; a superb type of manly beauty." The Mahatma K.H. referred to him humorously as "my bulky brother." He was not proficient in English and spoke of himself as using words and phrases "lying idle in my friend's brain" -- meaning, of course, the brain of the Mahatma K.H.In 1870, the same year that Keshub visited England, two other Indians took ship from England to America. They were a Bombay textile magnate called Moolji Thackersey (Seth Damodar Thackersey Mulji, died 1880) and Mr. Tulsidas. Josephine Ransom, an early historian of the Theosophical Society, writes that they were “on a mission to the West to see what could be done to introduce Eastern spiritual and philosophic ideas.” Traveling on the same boat was Henry Olcott, fresh from his experiences in London’s spiritualist circles. Olcott was sufficiently impressed by this shipboard meeting to keep a framed photograph of the two Indians on the wall of the apartment he was sharing with Blavatsky in 1877. It was one evening in that year that a visitor who had traveled in India (sometimes identified as James Peebles) remarked on the photograph. Olcott writes in his memoirs of the consequences of this extraordinary series of coincidences:I took it down, showed it to him, and asked if he knew either of the two. He did know Moolji Thackersey and had quite recently met him in Bombay. I got the address, and by the next mail wrote to Moolji about our Society, our love for India and what caused it. In due course he replied in quite enthusiastic terms, accepted the offered diploma of membership, and told me about a great Hindu pandit and reformer, who had begun a powerful movement for the resuscitation of pure Vedic religion.

This reformer was Swami Dayananda Saraswati (1824-1882). In 1870 he was still an eccentric traveling preacher with no aspirations to international influence: something that grew on him precisely after meeting the Brahmo Samajists. He met Devandranath [Debendranath] Tagore in 1870; in 1873 Keshub Chunder Sen gave him the advice (which he took) to stop wearing only a loincloth and speaking only Sanskrit. Indefatigably stumping round the subcontinent, Dayananda founded his “powerful movement,” the Arya Samaj, in 1875. This chronology suggests that in 1870 Thackersey was probably coming to America as a representative of the Brahmo Samaj, but that by the time Olcott got in touch with him again, he had transferred his allegiance to the Arya Samaj.

The Arya Samaj was more radical than any wing of the Brahmo Samaj, on which it was partially modeled. Dayananda was a monotheist who believed in the Vedas as the sole revealed scripture and the basis for a universal religion. The various gods addressed in the Vedic hymns (Agni, Indra, etc.), he explained as aspects of the One, and he was prepared to demonstrate how these ancient texts contained all possible knowledge of man, nature, and the means of salvation and happiness. Of the quarrels between the various religions, he wrote: “My purpose and aim is to help in putting an end to this mutual wrangling, to preach universal truth, to bring all men under one religion so that they may, by ceasing to hate each other and firmly loving each other, life in peace and work for their common welfare.” He had no respect whatever for Brahmanism: for their scriptures, rituals, polytheism, caste system, and discrimination against women. Unfortunately for his opponents, he was immensely learned and articulate, could out-argue most pundits, and had, in the last resort (which often seems to have occurred) the advantage of being 6’9” tall and broad to match.

From Dayananda’s point of view, the Brahmo Samajists had erred both in their failure to recognize the supremacy of the Vedas, and in their too-ready embrace of the errors of other religions. They were moreover too addicted to Brahmanic customs and privileges. Here is a contemporary summary of his social principles:He says that no inhabitant of India should be called a Hindu, that an ignorant Brahmin should be made a Shudra, and a Shudra, who is learned, well-behaved and religious should be made a Brahmin. Both men and women should be taught Language, Grammar, Dharmashastras, Vedas, Science and Philosophy. Women should receive special education in Chemistry, Music and Medical Science; they should know what foods promote health, strength and vigour. He condemns child marriage as the root of the most of the evils. A girl should be educated and married at the age of twenty. If a widow wants to remarry, she should be allowed to do so. According to his opinion, there is no particular difference between the householder and the sannyasi.

It is not surprising that the Theosophists in New York took kindly to the Arya Samaj, at first through correspondence with Thackersey, then through the Bombay branch head, Hurrychund Chintamon, and lastly through Dayananda himself. The two societies were united for a time, though the Theosophists were disillusioned as soon as they discovered the strength of Dayananda's Vedic fundamentalism and his hostility to all other religions. On Dayananda's unexpected death, Blavatsky wrote a generous obituary in The Theosophist for December 1883. She appreciated him for defending what he saw as the best of his native heritage against the priestcraft of Brahmins and Christians alike, and for his leadership in an enlightened social policy of which she could only have approved.

As the Arya Samaj continued to flourish after Dayananda's death, it became a rallying point for that movement of Hindu nationalism that wanted neither to turn back the clock to Brahmanic theocracy, nor to embrace Western materialism along with the benefits of science and technology. What Rammohun Roy had set in motion, the Arya Samaj carried forward into the era of the Indian National Congressand the independence movement of the twentieth century. Dayananda himself died -- some said poisoned -- at the time when his mission was beginning to have real success among the North Indian rulers, but he had done enough to be celebrated as a father-figure by leaders of Indian independence such as [url]Jawaharlal Nehru[/url], Mahatma Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, and Aurobindo Ghose.

-- The Theosophical Enlightenment, by Joscelyn Godwin

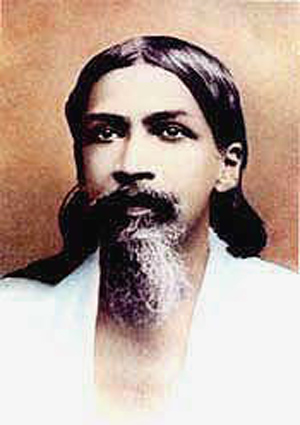

A representation of Swami Dayananda Saraswati

Swami Dayananda Saraswati (स्वामी दयानन्द सरस्वती) (1824 - 1883) was an important Hindu religious scholar born in Gujarat, India. He is best known as the founder of the Arya Samaj "Society of Nobles," a great Hindu reform movement, founded in 1875. He was a sanyasi (one who has renounced all worldly possessions and relations) from his boyhood. He was an original scholar, who believed in the infallible authority of the Vedas. Dayananda advocated the doctrine of karma, skepticism in dogma, and emphasized the ideals of brahmacharya (celibacy and devotion to God). The Theosophical Society and the Arya Samaj were united for a certain time under the name Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj.

Dayananda was an important Hindu reformist whose views did much to promote gender-equality, democracy, education, as well as a new confidence in India's cultural past and future capabilities. In some respects, he qualifies as an architect of modern India as am emerging scientific and technological power. Aspects of his views impacted negatively on inter-religious relations, however, and contributed to extreme forms of Hindu nationalism which denies non-Hindus their complete civil rights. Yet, in his own day, when he spoke of the superiority of Hindu culture and religion, he was doing so in defense of what Europeans in India had insulted and denigrated. A consequence of assuming racial, cultural, or religious superiority over others is that they retaliate, and reverse what is said about them. The Arya Samaj is now a worldwide movement.

Upbringing

Born in Kathiawi, Gujerat, Dayananda's parents were wealthy members of the priestly class, the Brahmins (or Brahmans). Although raised as an observant Hindu, in his late teens Dayananda turned to a detailed study of the Vedas, convinced that some contemporary practices, such as the veneration of images (murtis) was a corruption of pure, original Hinduism. His inquiries were prompted by a family visit to a temple for overnight worship, when he stayed up waiting for God to appear to accept the offerings made to image of the God Shiva. While everyone else slept, Dayananda saw mice eating the offerings kept for the God. Utterly surprised, he wondered how a God, who cannot even protect his own "offerings," would protect humanity. He later argued with his father that they should not worship such a helpless God. He then started pondering the meaning of life and death, and asking questions that worried his parents.

Quest for liberation

In 1845, he declared that he was starting a quest for enlightenment, or for liberation (moksha), left home and started to denounce image-veneration. His parents had decided to marry him off in his early teens (common in nineteenth century India), so instead Dayananda chose to become a wandering monk. He learned Panini's Grammar to understand Sanskrit texts. After wandering in search of guidance for over two decades, he found Swami Virjananda (1779-1868) near Mathura who became his guru. The guru told him to throw away all his books in the river and focus only on the Vedas. Dayananda stayed under Swami Virjananda's tutelage for two and a half years. After finishing his education, Virjananda asked him to spread the concepts of the Vedas in society as his gurudakshina ("tuition-dues"), predicting that he would revive Hinduism.

Reforming Hinduism

Dayananda set about this difficult task with dedication, despite attempts on his life. He traveled the country challenging religious scholars and priests of the day to discussions and won repeatedly on the strength of his arguments. He believed that Hinduism had been corrupted by divergence from the founding principles of the Vedas and misled by the priesthood for the priests' self-aggrandizement. Hindu priests discouraged common folk from reading Vedic scriptures and encouraged rituals (such as bathing in the Ganges and feeding of priests on anniversaries) which Dayananda pronounced as superstitions or self-serving.

He also considered certain aspects of European civilization to be positive, such as democracy and its emphasis on commerce, although he did not find Christianity at all attractive, or European cultural arrogance, which he disliked intensely. In some respects, his ideas were a reaction to Western criticism of Hinduism as superstitious idolatry. He may also have been influenced by Ram Mohan Roy, whose version of Hinduism also repudiated image-veneration. He knew Roy's leading disciple, Debendranath Tagore and for a while had contemplated joining the Brahmo Samaj but for him the Vedas were too central

In 1869, Dayananda set up his first Vedic School, dedicated to teaching Vedic values to the fifty students who registered during the first year. Two other schools followed by 1873. In 1875, he founded the Arya Samaj in 1875, which spearheaded what later became known as a nationalist movement within Hinduism. The term "fundamentalist" has also been used with reference to this strand of the Hindu religion.

The Arya Samaj

ओ३म् O3m (Aum), considered by the Arya Samaj to be the highest and most proper name of God.

The Arya Samaj unequivocally condemns idol-veneration, animal sacrifices, ancestor worship, pilgrimages, priestcraft, offerings made in temples, the caste system, untouchability, child marriages, and discrimination against women on the grounds that all these lacked Vedic sanction. The Arya Samaj discourages dogma and symbolism and encourages skepticism in beliefs that run contrary to common sense and logic. To many people, the Arya Samaj aims to be a "universal church" based on the authority of the Vedas. Dayananda taught that the Vedas are rational and contain universal principles. Fellow reformer Vivekananda also stressed the universal nature of the principles contained in Hindu thought, but for him the Ultimate was trans-personal, while Dayananda believed in a personal deity.

Among Swami Dayananda's immense contributions is his championing of the equal rights of women—such as their right to education and reading of Indian scriptures—and his translation of the Vedas from Sanskrit to Hindi so that the common person may be able to read the Vedas. The Arya Samaj is rare in Hinduism in its acceptance of women as leaders in prayer meetings and preaching. Dayananda promoted the idea of marriage by choice, strongly supported education, pride in India's past, in her culture as well as in her future capabilities. Indeed, he taught that Hinduism is the most rational religion and that the ancient Vedas are the source not only of spiritual truth but also of scientific knowledge. This stimulated a new interest in India's history and ancient disciples of medicine and science. Dayananda saw Indian civilization as superior, which some later developed into a type of nationalism that looked on non-Hindus as disloyal.

For several years (1879-1881), Dayananda was courted by the Theosophist, Helena Blavatsky, and Henry Steel Olcott, who were interested in a merger which was temporarily in place. However, their idea of the Ultimate Reality as impersonal did not find favor with Dayananda, for whom God is a person, and the organizations parted.

Dayananda's views on other religions

Far from borrowing concepts from other religions, as Raja Ram Mohan Roy had done, Swami Dayananda was quite critical of Islam and Christianity as may be seen in his book, Satyartha Prakash. He was against what he considered to be the corruption of the pure faith in his own country. Unlike many other reform movements within Hinduism, the Arya Samaj's appeal was addressed not only to the educated few in India, but to the world as a whole, as evidenced in the sixth of ten principle of the Arya Samaj.[1]

Arya Samaj, like a number of other modern Hindu movements, allows and encourages converts to Hinduism, since Dayananda held Hinduism to be based on "universal and all-embracing principles" and therefore to be "true." "I hold that the four Vedas," he wrote, "the repository of Knowledge and Religious Truths- are the Word of God …They are absolutely free from error and are an authority unto themselves."[2] In contrast, the Gospels are silly, and "no educated man" could believe in their content, which contradicted nature and reason.

Christians go about saying "Come, embrace my religion, get your sins forgiven and be saved" but "All this is untrue, since had Christ possessed the power of having sins remitted, instilling faith in others and purifying them, why would he not have freed his disciples from sin, made them faithful and pure," citing Matthew 17:17.[3] The claim that Jesus is the only way to God is fraudulent, since "God does not stand in need of any mediator," citing John 14: 6-7. In fact, one of the aims of the Arya Samaj was to re-convert Sikhs, Muslims and Christians. Sikhs were regarded as Hindus with a distinct way of worship. Some Gurdwaras actually fell under the control of the Arya Samaj, which led to the creation of a new Sikh organization to regain control of Sikh institutions. As the political influence of the movement grew, this attitude towards non-Hindu Indian's had a negative impact on their treatment, inciting such an event as the 1992 destruction of the Mosque at Ayodhia. There and elsewhere, Muslims were accused of violating sacred Hindu sites by bulding Mosques where Temples had previously stood. The Samaj has been criticized for aggressive intolerance against other religions.<see>Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Arya Samaj. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

However, given the hostility expressed by many Christian missionaries and colonial officials in India towards the Hindu religion, which they often held in open contempt, what Dayananda did was to reverse their attitude and give such people a taste of their own medicine.

Support for democracy

He was the among the first great Indian stalwarts who popularized the concept of Swaraj—right to self-determination vested in an individual, when India was ruled by the British. His philosophy inspired nationalists in the mutiny of 1857 (a fact that is less known), as well as champions such as Lala Lajpat Rai and Bhagat Singh. Dayananda's Vedic message was to emphasize respect and reverence for other human beings, supported by the Vedic notion of the divine nature of the individual—divine because the body was the temple where the human essence(soul or "Atma") could possibly interface with the creator ("ParamAtma"). In the 10 principles of the Arya Samaj, he enshrined the idea that "All actions should be performed with the prime objective of benefiting mankind" as opposed to following dogmatic rituals or revering idols and symbols. In his own life, he interpreted Moksha to be a lower calling (due to its benefit to one individual) than the calling to emancipate others. The Arya Samaj is itself democratically organized. Local societies send delegates to regional societies, which in turn send them to the all India Samaj.

Death

Dayananda's ideas cost him his life. He was poisoned in 1883, while a guest of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. On his deathbed, he forgave his poisoner, the Maharaja's cook, and actually gave him money to flee the king's anger.

Dayananda Sarasvati, original name Mula Sankara, (born 1824, Tankara, Gujarat, India—died October 30, 1883, Ajmer, Rajputana), Hindu ascetic and social reformer who was the founder (1875) of the Arya Samaj (Society of Aryans [Nobles]), a Hindu reform movement advocating a return to the temporal and spiritual authority of the Vedas, the earliest scriptures of India.

-- Dayananda Sarasvati, by Britannica.com

Legacy

The Arya Samaj remains a vigorous movement in India, where it has links with several other organizations including some political parties. Dayananda and the Arya Samaj provide the ideological underpinnings of the Hindutva movement of the twentieth century. Ruthven regards his "elevation of the Vedas to the sum of human knowledge, along with his myth of the Aryavartic kings" as religious fundamentalism, but considers its consequences as nationalistic, since "Hindutva secularizes Hinduism by sacralizing the nation." Dayananda's back-to-the-Vedas message influenced many thinkers.[4] The Hindutva concept considers that only Hindus can properly be considered India. Organizatuions such as the RSS (the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party]] were influenced by the Arya Samaj.

Sri Aurobindo

Dayananda also influenced Sri Aurobindo, who decided to look for hidden psychological meanings in the Vedas.[5] Dayananda's legacy may have had a negative influence in encouraging Hindu nationalism that denies the full rights of non-Hindus. On the other hand, he was a strong democrat and an advocate of women's rights. His championship of Indian culture, and his confidence in India's future ability to contribute to science, did much to stimulate India's post-colonial development as a leading nation in the area of technology especially.

Works

Dayananda Saraswati wrote more than 60 works in all, including a 14 volume explanation of the six Vedangas, an incomplete commentary on the Ashtadhyayi (Panini's grammar), several small tracts on ethics and morality, Vedic rituals and sacraments and on criticism of rival doctrines (such as Advaita Vedanta). The Paropakarini Sabha located in the Indian city of Ajmer was founded by the Swami himself to publish his works and Vedic texts.

• Satyartha Prakash/Light of Truth. Translated to English, published in 1908; New Delhi: Sarvadeshik Arya Pratinidhi Sabha, 1975.

• An Introduction to the Commentary on the Vedas. Ed. B. Ghasi Ram, Meerut, 1925; New Delhi : Meharchand lachhmandas Publications, 1981.

• Glorious Thoughts of Swami Dayananda. Ed. Sen, N.B. New Delhi: New Book Society of India.

• Autobiography. Ed. Kripal Chandra Yadav, New Delhi: Manohar, 1978.

• The philosophy of religion in India. Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, 2005. ISBN 8180900797

Notes

1. New Zealand Arya Samaj, Ten Principles of the Arya Samaj. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

2. Griffiths, p. 202-3.

3. Griffiths, p. 200.

4. Ruthven, 108.

5. Sri Aurobindo, The Secret of the Veda (Volume 10). Retrieved September 13, 2007

References

• Griffiths, Paul J. Christianity Through Non-Christian Eyes. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1990. ISBN 0883446618

• Lata, Prem. Swami Dayananda Sarasvati. New Delhi: Sumit Publications, 1990. ISBN 978-8170001140

• Ruthven, Malise. Fundamentalism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0199212705

• Salmond, N.A. Hindu Iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and Nineteenth Century Polemics Against Idolatry. Waterloo, Ont: Published for the Canadian Corp. for Studies in Religion by Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0889204195

• Sarasvati, Dayananda. Autobiography of Swami Dayanand Saraswati. New Delhi: Manohar Book Service, 1976.

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2017.

• Satyarth Prakash - THE "LIGHT OF TRUTH" by Swami Dayanand Online book.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats. The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

• Dayananda Saraswati history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

• History of "Dayananda Saraswati"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

***********************************

Dayananda Sarasvati

Hindu leader

by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Accessed: 3/21/21

Dayananda Sarasvati, original name Mula Sankara, (born 1824, Tankara, Gujarat, India—died October 30, 1883, Ajmer, Rajputana), Hindu ascetic and social reformer who was the founder (1875) of the Arya Samaj (Society of Aryans [Nobles]), a Hindu reform movement advocating a return to the temporal and spiritual authority of the Vedas, the earliest scriptures of India.

Dayananda received the early education appropriate to a young Brahman of a well-to-do family. At the age of 14 he accompanied his father on an all-night vigil at a Shiva temple. While his father and some others fell asleep, mice, attracted by the offerings placed before the image of the deity, ran over the image, polluting it. The experience set off a profound revulsion in the young boy against what he considered to be senseless idol worship. His religious doubts were further intensified five years later by the death of a beloved uncle. In a search for a way to overcome the limits of mortality, he was directed first toward Yoga (a system of mental and physical disciplines). Faced with the prospect of a marriage being arranged for him, he left home and joined the Sarasvati order of ascetics.

For the next 15 years (1845–60) he traveled throughout India in search of a religious truth and finally became a disciple of Swami Virajananda. His guru, in lieu of the usual teacher’s fees, extracted a promise from Dayananda (the name taken by him at the time of his initiation as an ascetic) to spend his life working toward a reinstatement of the Vedic Hinduism that had existed in pre-Buddhist India.

Dayananda first attracted wide public attention for his views when he engaged in a public debate with orthodox Hindu scholars in Benares (Varanasi) presided over by the maharaja of Benares. The first meeting establishing the Arya Samaj was held in Bombay (now Mumbai) on April 10, 1875. Although some of Dayananda’s claims to the unassailable authority of the Vedas seem extravagant (for example, modern technological achievements such as the use of electricity he claimed to have found described in the Vedas), he furthered many important social reforms. He opposed child marriage, advocated the remarriage of widows, opened Vedic study to members of all castes, and founded many educational and charitable institutions. The Arya Samaj also contributed greatly to the reawakening of a spirit of Indian nationalism in pre-Independence days.

Dayananda died after vigorous public criticism of a princely ruler, under circumstances suggesting that he might have been poisoned by one of the maharaja’s supporters, but the accusation was never proved in court.

***********************************

The Saint who Declared Swaraj

by Rajendra Chaddha

Voice of the Nation Organiser

November 27, 2019

Swami Dayanand Saraswati,(Feb 12, 1824–Oct 30, 1883

The personality and teachings of Swami Dayanand Saraswati influenced most of the revolutionaries during the freedom movement. He was the pioneer of neo-nationalism in politics

Today, it will surprise many to know that under British rule, a saint had demanded Swaraj in the year 1876, much before Bal Gangadhar Tilak. He was Swami Dayanand. He was the father of India’s Independence movement. If we study the history of India’s independence movement, we could know that most of the leaders, patriots and revolutionaries of that period who sacrificed their lives for freedom, were influenced by the personality and teachings of Swami Dayanand. Among the Indian revolutionaries, Shyamji Krishna Verma, Swami Shraddhanand and Lala Lajpat Rai were his disciples and ardent devotees. Even revolutionary patriots like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, Gendalal Dixit, Swami Bhavani Dayal, Bhai Parmanand, Bhagat Singh, Ramprasad Bismil, Yashpal and Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi had imbibed patriotism from the Arya Samaj. Not only this, even Mahatma Gandhi was substantially influenced by Dayanand’s teachings and vision. The remarkable thing is that Mahatma Gandhi’s Guru Gopalakrishna Gokhale and Gokhale’s Guru Justice Govind Ranade were not only the ultimate disciples of Dayanand but also the distinguished office bearers of the Paropakarini Sabha founded by Dayanand.

According to Indravidya Vachaspati, after the revolution of 1857, the first name in the list of great men whom we can call the mental, social and cultural successors of that revolution is of Swami Dayanand Saraswati. It would not be an exaggeration to call Swami Dayanand the pioneer of neo-nationalism in politics. Even Anne Besant said that Dayanand was the first person who wrote that ‘India is for Indians’.

According to Lala Lajpat Rai, “Swami Dayanand donated my soul to me. I am indebted to him for being his ‘manasputra’. On reading the touching and heartfelt description of the plight of the country in Maharishi’s ‘Satyarth Prakash’ and experiencing Dayanand’s patriotic spirit, patriot and ardent follower of the Sanatan Dharma Madanmohan Malaviya’s eyes used to get filled with tears”. In light of all the above statements, it can be said that Dayanand has given inspiration and strength to the Indian freedom movement and revolutionaries through his nationalist ideology. His emergence as a champion of the Hindu’s and Indian Nation was at a time when Indian culture was beset by foreign influences. The educated class was forgetting its self-respect and ancient dignity due to the glare of Western civilisation. He dissolved this folly of Indians and taught them a beautiful lesson in nationalism.

Swami Dayanand was born on February 12, 1824 in Tankara in Morvi state of Kathiawar, Gujarat. Born in the Moola constellation Sagittarius, he was named Mool Shankar. Moolshankar left the normal household life in search of truth in the year 1846. Then, under Guru Virjanand, Mool Shankar studied Panini’s grammar, Patanjali-Yogasutra and Veda-Vedang. The Guru asked him to eradicate the ignorance of dissent and spread the light of Vedic religion with the light of Vedic Dharma as Dakshina to him. The result was that he made it his goal to rejuvenate the Hindu society of Aryavarta, regardless of the opposition and condemnation of anyone. Swami Dayanand’s biggest contribution was to empower and activate the Hindu people. He sent a message of regenerative power to the people who had remained weak from centuries of invasion. “Our existence is going to be erased from the land in the absence of strength,” he said. No one else had done empowerment of the society in India as that of Dayanand and Vivekananda.

Swami Dayanand was a strong supporter of education and wanted to spread it widely. He favoured proper education to women in the country. He considered women to be revered. Presenting the description of Atharvaveda, he said the girls should also follow the Brahmacharya and achieve education. He wanted the boys and girls to observe unbroken Brahmacharya in thought, words and action while performing a restrained life during their period of education. He wanted to impress English educated youth with the dignity of Indian languages. The use of Hindi language in his book ‘Satyarth Prakash’ suggests that he was the leader of public awakening and it was his programme to make the ancient ideals the wall of public life. He believed that one would automatically achieve social and political prosperity by having moral ideals. Thus, he was a strong supporter of temporal, moral and social emergence.

According to Maharishi Dayanand, the best goal of education is character-building. To achieve this objective, Gurukul Kangadi was established in the year 1902 on the banks of the Ganga near Haridwar. The character of the man is the sum of his various actions and desires, the sum of all the inclinations of his values. The way happiness and sorrow flow on his soul leave their imprint and their culture on him. The character of man is the fruit of the collection of these various impressions. We are the same as our thoughts are. Therefore, the character of the students is developed mainly in childhood and adolescence. The parents, guardians and teachers need to be fully alert in this regard. Swamiji asked to adopt the principle of simplicity in food, ethics, costumes and everywhere. He was of the opinion that there should be uniform food, clothes and accommodation for every student. This will be possible only when our standard of living is simple and pure. He has addressed the teachers and asked them to hold the above and said the Guru has to keep in his mind that knowledge of real religion is not possible without being alienated from wealth and worldly pleasures.

Paropakarini Sabha, formed in Meerut in 1880, was mainly tasked to print and publish the Vedas and Vedangas with proper interpretation. Aryma Samaj focussed on the protection of orphans, carrying out welfare activities and Vedic research

It is worth mentioning that famous German philosopher and educationist Herbert also considered the main goal of education as ‘ideal character building’. He has written in clear words that ‘the aim of education is to endow human beings with moral qualities. Morality is different from religiousness. Morality is the richness of human qualities. According to him, the essence of the sole and whole of education lies in morality. Herbert considers education as the basis for the development and refinement of qualities. His morality consists of the realisation of Satya, Shiva, Sundaram and Dharma.

Deputy Collector of Kashi, Raja Jayakrishnadas, met Swamiji (when Swamiji came to Kashi) in May 1874. In June 1874, Swami Dayanand started writing ‘Satyarth-Prakash’ to the Pandits. Shri Harvilas Sharda wrote life sketch of Rishi Dayanand in English, which he did in Allahabad. Swami Dayanand, who founded the Arya Samaj on April 7, 1875 in Mumbai, gave the slogan to return to the Vedas. He formed the basis of his philosophy of karma theory, rebirth, celibacy and renunciation while writing commentary on the Vedas. He considered untouchability against the Vedas and he has a major contribution in freeing the Hindu caste from the curse of untouchability. The first edition of ‘Satyarth-Prakash’ was printed in Kashi in the year 1875. By the time of Swamiji's lifetime till Deepavali 1883 October 30 (Samvat 1940), only 11 Samullas of it were printed in the Vedic Press at Prayag. For this reason, the second edition came to light in December 1884. Among all his writings ‘Satyarth Prakash’ is the principal one. Reference of a total of 377 texts can be seen in this, in which evidence of 210 books are given. Examples of 1542 Veda Mantras or Shlokas are given in this book.

If a research scholar of today wants to write a text with such references from an up-to-date library of Sanskrit of a university where all the texts are available, it would take years, which was written by Rishi Dayanand in three months. This book gave birth to a new social outlook. Inspiration to study foreign languages as much as possible is there in the ‘Satyarth Prakash’, but it urges to give first place to his own language Sanskrit and Hindi.

Maharishi Dayananda accepted the Vedas and Upanishads, adopting only the ancient and his interpretation of the Upanishads. He followed his own method of interpretation. He formed the Arya Samaj and his primary purpose behind it was to define and organise the entire Indian society as a cultural unit. The Arya Samaj contributed much in increasing the nationalist thought stream as seen today. It mainly affected the states of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Paropakarini Sabha was primarily founded in Meerut in 1880. Its original purpose was printing and publication of the Vedas and Vedangas by interpreting them. Propagation of religion, protection of orphans, and doing other public welfare activities have been taken as activities of Arya Samaj, along with the publication of books, doing of Vedic research and studies. Maharishi Dayanand started purification movement by inspiring people who had converted to other religions to return back to Hinduism. Under this movement, by purifying millions of Muslims and Christians, they made a comeback to the true Sanatan Vedic religion. It was started by Swami Shraddhanand on February 11, 1923 by establishing the Bharatiya Shuddhi Sabha.

(The writer is a member of the central team, Prajna Pravah)

**********************************

Krishna Varma admired Swami Dayananda Saraswati's cultural nationalism and believed in Herbert Spencer's dictum that "Resistance to aggression is not simply justified, but imperative". A graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, he returned to India in the 1880s and served as divan (administrator) of a number of princely states, including Ratlam and Junagadh. He preferred this position to working under what he considered the alien rule of Britain. However, a supposed conspiracy of local British officials at Junagadh, compounded by differences between Crown authority and British Political Residents regarding the states, led to Varma's dismissal. He returned to England, where he found freedom of expression more favourable. Varma's views were staunchly anti-colonial, extending even to support for the Boers during the Second Boer War in 1899.

Krishna Varma co-founded the IHRS [Indian Home Rule Society] in February 1905, with Bhikaji Cama, S.R. Rana, Lala Lajpat Rai and others, as a rival organisation to the British Committee of the Congress. Subsequently, Krishna Varma used his considerable financial resources to offer scholarships to Indian students in memory of leaders of the 1857 uprising, on the condition that the recipients would not accept any paid post or honorary office from the British Raj upon their return home. These scholarships were complemented by three endowments of 2000 Rupees courtesy S.R. Rana, in memory of Rana Pratap Singh. Open to "Indians only", the IHRS garnered significant support from Indians – especially students – living in Britain. Funds received by Indian students as scholarships and bursaries from universities also found their way to the organisation. Following the model of Victorian public institutions, the IHRS adopted a constitution. The aim of the IHRS, clearly articulated in this constitution, was to "secure Home Rule for India, and to carry on a genuine Indian propaganda in this country by all practicable means". It recruited young Indian activists, raised funds, and possibly collected arms and maintained contact with revolutionary movements in India. The group professed support for causes in sympathy with its own, such as Turkish, Egyptian and Irish republican nationalism.

The Paris Indian Society, a branch of the IHRS, was launched in 1905 under the patronage of Bhikaji Cama, Sardar Singh Rana and B.H. Godrej. A number of India House members who later rose to prominence – including V.N. Chatterjee, Har Dayal and Acharya and others – first encountered the IHRS through this Paris Indian Society. Cama herself was at this time deeply involved with the Indian revolutionary cause, and she nurtured close links with both French and exiled Russian socialists. Lenin's views are thought to have influenced Cama's works at this time, and Lenin is believed to have visited India House during one of his stays in London. In 1907, Cama, along with V.N. Chatterjee and S.R. Rana, attended the Socialist Congress of the Second International in Stuttgart. There, supported by Henry Hyndman, she demanded recognition of self-rule for India and in a famous gesture unfurled one of the first Flags of India.

-- India House, by Wikipedia

Shyamji Krishna Varma (4 October 1857 – 30 March 1930) was an Indian revolutionary fighter, an Indian patriot, lawyer and journalist who founded the Indian Home Rule Society, India House and The Indian Sociologist in London. A graduate of Balliol College, Krishna Varma was a noted scholar in Sanskrit and other Indian languages. He pursued a brief legal career in India and served as the Divan of a number of Indian princely states in India. He had, however, differences with Crown authority, was dismissed following a supposed conspiracy of local British officials at Junagadh and chose to return to England. An admirer of Dayanand Saraswati's approach of cultural nationalism, and of Herbert Spencer, Krishna Varma believed in Spencer's dictum: "Resistance to aggression is not simply justified, but imperative".

In 1905 he founded the India House and The Indian Sociologist, which rapidly developed as an organised meeting point for radical nationalists among Indian students in Britain at the time and one of the most prominent centres for revolutionary Indian nationalism outside India. Krishna Varma moved to Paris in 1907, avoiding prosecution...

In 1875, Shyamji married Bhanumati, a daughter of a wealthy businessman of the Bhatia community and sister of his school friend Ramdas. Then he got in touch with the nationalist Swami Dayananda Saraswati, a radical reformer and an exponent of the Vedas, who had founded the Arya Samaj. He became his disciple and was soon conducting lectures on Vedic philosophy and religion. In 1877, a public speaking tour secured him a great public recognition. He became the first non-Brahmin to receive the prestigious title of Pandit by the Pandits of Kashi in 1877. He came to the attention of Monier Williams, an Oxford professor of Sanskrit who offered Shyamji a job as his assistant.

Oxford

Shyamji arrived in England and joined Balliol College, Oxford on 25 April 1879 with the recommendation of Professor Monier Williams. Passing his B.A. in 1883, he presented a lecture on "the origin of writing in India" to the Royal Asiatic Society. The speech was very well received and he was elected a non-resident member of the society. In 1881 he represented India at the Berlin Congress of Orientalists.

Legal career

He returned to India in 1885 and started practice as a lawyer. Then he was appointed as Diwan (chief minister) by the King of Ratlam State; but ill health forced him to retire from this post with a lump sum gratuity of RS 32052 for his service. After a short stay in Mumbai, he settled in Ajmer, headquarters of his Guru Swami Dayananda Saraswati, and continued his practice at the British Court in Ajmer. He invested his income in three cotton presses and secured sufficient permanent income to be independent for the rest of his life. He served for the Maharaja of Udaipur as a council member from 1893 to 1895, followed by the position of Diwan of Junagadh State. He resigned in 1897 after a bitter experience with a British agent that shook his faith in British Rule.

-- Shyamji Krishna Varma, by Wikipedia