by Anna Dorotea Teofilo

From Defining Authorship, Debating Authenticity: Problems of Authority from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

Edited by Roberta Berardi, Martina Filosa, and Davide Massimo

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Si non molestum est, hospes, consiste et lege.

Nauibus ueliuolis magnum mare saepe cucurri,

accessi terras conplures, terminus hicc est

quem mihi nascenti quondam Parcae cecinere.

Hic meas deposui curas omnesque labores,

sidera non timea hic nec nimbos nec: mare saeuom.

nec metuo sumptus ni quaestum uincere possit.

Alma Fides, tibi ago grates, sanctissuma diua,

fortuna infracta ter me fessum recreasti,

tu digna es quam mortales optent sibi cuncti.

Hospes uiue uale, in sumptum superet tibi semper,

qua non spreuisti hunc lapidem dignumq(ue) dicasti.

CIL IX 60= CLE 1533

If it is no bother, wayfarer, stop and read. On sail-flying ships did I roam the great sea and reach many lands; this is the end of which the Parcae sang at my birth. Here I have laid down my troubles and all my toils; neither do I dread the stars here nor the storms nor ruthless sea, and I do not fear that expense might exceed advantage. I thank you, kindly Fides, most holy goddess, who three times restored me from a broken fortune, and who is worthy of devotion from all mortals. Wayfarer, live and fare well, may you always have money to spend, for you did not overlook this gravestone, but proclaimed it worthy.1

The epitaph presents, from a first reading, conspicuous elements of interest: length and metric form, content and references, undefined details. It was published several times (either individually or in collections, cf. Henzen [1872], at IX 60 and CLE 1533, De Ruggiero/Vaglieri [1904] 3186, Alessandri [1997)) and has often been quoted by scholars, in various contexts and to different ends. On the one hand, it has been studied in relation to social and economic history, due to its allusion to commerce and trade routes in Roman Apulia and in the Mediterranean through the port of Brindisi (cf. Silvestrini [1987), Giardina [1989], Silvestrini [1998], Grelle et al. [2017)). Other points of comparison are with literary history and epigraphic tradition, with its originality of composition and the unusually high number of allusions to canonical authors, as it has been widely recognized (cf. La Penna [1979], Massaro [1983], Caviglia [1964], Cugusi [1985], Cugusi [20(4)). Nevertheless, after Plessis (1905) n. 17, the epitaph has seldom been analyzed in a systematic way incorporating these different points of interest. This has only been done by Tise (2001), which paid special concern to the social and economic implications of both its material and literary aspects; Franzoi (2004) has provided instead more of a stylistic and linguistic analysis. With this in mind, the present work intends to contribute further reflections and thoughts.

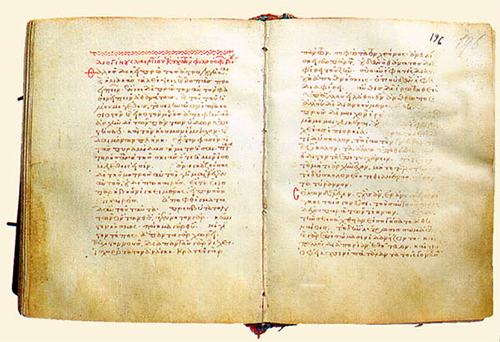

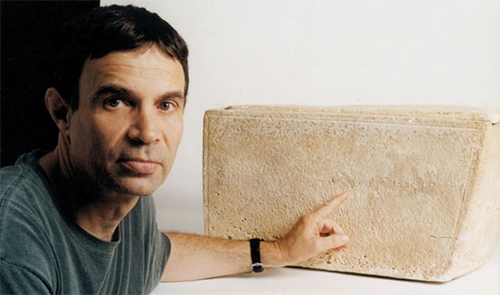

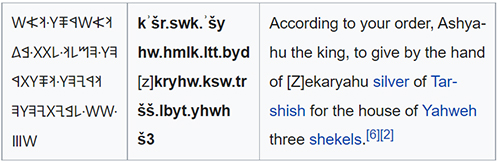

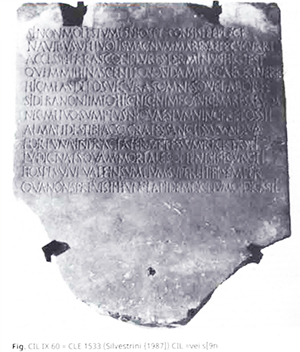

The inscription was uncovered in Brindisi during the dredging of the port, and exists across two matching fragments of a marble slab, found in 1869 and 1871 respectively (the former containing the last four lines). It was first published by Henzen (1872), who had received a record of the inscription, an account of its material features and a paper squeeze by the priest and archaeologist Giovanni Tarantini, long-time chief librarian in Brindisi. The inscription was later included in CIL and CLE. It is now housed in the Museo Archeologico Provinciale 'F. Ribezzo' in Brindisi (inv. 813), and measures 65,5 x 52,3 x 4,7 cm.

The letters are thinly cut, with clear serifs (but no shading), and some featuring curved horizontal strokes; there are some ornamental tall letters, as well as tall long I's and apices to mark long vowels. Words are divided by a consistent usage of interpuncta, with the only exception at I. 11 between in and sumptum, where the stonecutter must have regarded the collocation, perhaps unconsciously, as a single word. There is also an interpunctum at the end of I. 1 separating the first verse from those following it, marking out its distinctiveness as a conceptual and metric unit.2

All the palaeographic elements suggest a date between the second half of the 1st century AD and the early 2nd century AD.3 Bucheler was led to date the stone 'propius ab Augusto', back to the Julio-Claudian age, from the text of the inscription only. Judging from the closing dignumq(ue) dicasti he was also uncertain about its completeness. Actually, since the name and age of the deceased are missing, as well as any information about the dedicator, the gravestone must relate to a more elaborate monument.4

The text consists of a verse per line, the first one in slightly reduced module compared to the others, without any indent, protrusion, or similar devices.5 The 12 verses of the inscription are metrically consistent.6 The opening iambic senarius, addressing the wayfarer, is followed by hexameters: the first nine illustrate the deceased's life, with a succession of three verse sentences, each made up of three coordinated main clauses and a complement clause; the two closing hexameters appeal again to the wayfarer with friendly greetings.

It Is a remarkable first-person narration of a merchant who, after a life of travels and adventures, had met with the destiny foretold by the Parcae (II. 2- 4), and is now resting in peace with no further fear of shipwreck and financial distress (II. 5-7). He praises Fides for having managed to recover from three bankruptcies, presumably due to the faithfulness of his debtors (II. 8-10), and finally wishes health and affluence to the wayfarer who had stopped to read his epitaph (II. 11-12).

A peculiarity in spelling is to be noticed at I. 3 in the demonstrative form 'hicc',7 which grammarians found alongside 'hocc' in the most ancient manuscripts of Virgil.8 Grammarians actually preferred this alternative spelling to the more common one, as this syntactic doubling better explained the lengthening of the vowel (and consequent change in accent).9 The pronoun consists of the root ho-, with the thematic vowel inflexion, and the deictic particle -ce: the full forms 'hicce' and hocce', due to the economy of the spoken language, tended to drop the final vowel before a word starting in a vowel, thereby reducing the value of the double consonant.10 However, in this case the full form does not seem to have been chosen in order to fulfil scholarly tradition, but rather to distinguish the adjective 'hic' from the adverb 'hic' in a position where a long syllable is required. This was a specific semantic choice. The spelling 'saeuom' at I. 6, Instead, is probably preferred in order to avoid the double letter /V/ on the stone.

As concerns prosody, one must read 'meas' at I. 5 as a monosyllable due to synizesis.11 It is also to be noticed that the first four feet of II. 3, 9, and 10 are all spondees, whose rhythm emphasizes the merchant's adventures and hardships, and his final destiny and the intervention of Fides.

1. The address of the wayfarer follows the epigraphic tradition, which usually conveys in iambic metre, rather than dactylic, the conventional familiar appeal to stop and read. The most commonly attested collocation is 'hospes resiste' at the beginning of an iambic senarius,12 whereas 'consiste uiator' fits likewise at the end of a hexameter;13 here 'hospes consiste' is a suitable option for the middle of the verse-line.14

Other verbs or phrases may also replace, or combine with, 'lege' (or 'perlege') in such addresses. Together with 'resiste', one tends to find verba videndi, taking the grave as a concrete object or motion towards: e.g. 'perspice monumentum' in CIL 1 [2] 3146 (from Stabiae); 'tumulum aspic[e]' in CLE 63 (= CIL V 6808 and CIL I [2] 2161, from Eporedia); 'tumulum contempla' in CLE 83 (= CIL IX 2128, from near Beneuentum); 'hoc ad grumum ... aspice / ubei continentur ossa' in CLE 74 (= CIL VI 9545 and CIL I [2] 1212, from Rome). Together with 'consiste', on the other hand, one rather finds verba sentiendi, taking abstract objects or governing a complement clause, suggesting a more subtly emotive rather than straightforwardly tactile act: e.g. 'mea fata ... percipe' in AE 1996, 453 (from Luceria); 'uide quam indigne raptus' in CLE 1007 (= CIL XIII 7070, from Mainz); 'uide quam ua[nu]m' in AE 1985, 330 (from Peltuinum, in Samnium); 'casus hominum cogita' in AE 1972, 74 (from Aquino).

Therefore, as well as the spoken familiarity conveyed by the iambic metre, one recognizes a loftier aim in using 'consiste'. It is nevertheless striking that the stylistic choice has been made in the first verse to defer the actual appeal to the reader-viewer by opening the composition with a fine polite formula.

'Si non molestum est'15 is well documented, both in this analytic form, and even more so in the synthetic form 'nisi molestum est'. In the first case the negation relates to the adjective or verb, depending on its position, whereas in the second case the whole hypothetical clause is negated by the conjunction; the contracted spelling 'molestumst', which reflects the oral pronunciation, is sometimes attested as well.

In literature, the phrase occurs frequently in comedy,16 once in Lucil. 987 Marx (= 1081 Krenkel)17 'Si noenu molestum est', once in Catull. 55.1 'Si forte non molestum est', and often in Cicero's works;18 in the early imperial age the usage is limited to a couple of indirect speeches in Livius,19 Mart. 1.96.1 'Si non molestum est teque non piget' and 5.6.1 'Si non est grave nec nimis molestum'.20 All these contexts pertain to the spoken language, from which the phrase must come, or to meta-literature. It is further possible that the usage had acquired an old-fashioned feel by the time of our inscription.21

In epigraphy, there are two near-identical attestations from the Republican age, also in iambic metre: CLE 118, 1 (= CIL X 5371, from Interamna Lirenos, in Campania) 'Hospes resiste et nisi molestust perlege' and CIL I [2] 3146, 1 (from Stabiae) 'Hospes resiste et nisi mole(s)tus[t] perspice'; two further examples, in dactylic metre, come from the early empire: AE 1986, 166b, 1 (from Pompeii, middle of the 1st century AD) 'Hospes paullisper morare si non est molestum' and CLE 1125, 2-3 (= CIL IX 3358, from Pinna Vestina, in Samnium, between the 1st and the 2nd century AD) 'Hospes, si non es[t] lasso tibi forte molestum, / oramus lecto nomine pauca legas'. Even though such formulas were not unexpected as forms of address to the passer-by,22 their placement at the very opening of a composition suggests special politeness: the only comparison seems to be CLE 1013, 1 (= CIL VI 26020) 'Si graue non, hosp[es, fuerit] remorare uiator'.

2-4. The first biographical sequence provides the reader-viewer with an overall sense, intentionally suspended and undefined, of the deceased's identity. The dignified tone of the opening and closing words aim at grabbing attention, with two literary references in alliterative collocation; except for these, the language is appropriate to the pragmatic ends of the inscription.

2. A great contrast is perceptible at the beginning of the first hexameter, not only due to the switch in metre but also to the solemnity of 'nauibus ueliuolis', a quotation from Enn. Ann. 387-8 Vahlen2 (= 378-9 Skutsch)23 'Quom procul aspiciunt hostes accedere uentis / nauibus ueliuolis'. The position in the verse is identical too, and the echo is even more emphasized by 'accessi' at I. 3.

The rare Ennian adjective, although more common than the even rarer participial compound 'ueliuolans',24 refers to 'mare' in Laev. Carm. fr. 14 Blansdorf25 'Tu qui permensus ponti maria alta / ueliuola', in Verg. Aen. 1.223-4 'Iuppiter ... / despiciens mare ueliuolum' and in Ov. Pont. 4.16.21 'Veliuolique maris uates'; in Lucr. 5.1442 'mare ueliuolis florebat' it is substantivized and has instrumental function, as in our inscription. One might suspect Virgilian influence on our passage, with the prayer of Venus to Jupiter to end Aeneas' hardships presenting a relevant analogy to our merchant's story.26

The following alliterative collocation 'magnum mare' occurs in Lucr. 2.553 'Disiactare solet magnum mare transtra cauernas', where it occupies the same position in the verse, even though the adjective precedes the noun in Lucretius. Both authors, Lucretius and the composer of our epitaph, must have perceived the metric euphony created by the hephthemimeral caesura and bucolic diaeresis, although we need not assume any direct literary borrowing here: the collocation is highly attested, in different orders and positions in the verse, in didactic poetry. Such a phonic combination is likely to have originated in the spoken vernacular.27

'Mare magnum' too is found elsewhere, variously inflected,28 in prose and poetry, the earliest being Liv. Andr. Trag. 33 Ribbeck3 (= 25 Schauer) 'Aruaque putria et mare magnum': for the same reasons pointed out above, it is unlikely we are dealing either with an allusion to the beginning of Andronicus' Odyssey,29 or to the sepulchral remake by Catull. 101;30 equally, the merchant's story is not intended to be an erudite development on the widespread epigraphic theme of travel.31

The verb 'currere' meaning 'to sail' is only documented in poetry; especially distinctive is its transitive construction in taking 'mare' or synonyms as a direct object.32 The scene evoked can be compared to Horatian passages about the dangers of sailing, and restless merchants escaping poverty: Sat. 1.1.29-30 'Nautaeque',33 'per omne / audaces mare qui currunt' and Epist. 1.1.45-46 'Impiger extremos curris mercator ad Indos / per mare pauperiem fugiens'. 5uch a realistic picture affects Ulysses' character too, yearning no more for home, but rather mercantile profit: Sat. 2.5 parodies a common anti-heroic vision, not so distant from our epitaph's values.34 Furthermore, Hor. Epist. 1.11.27 'Caelum, non animum mutant, qui trans mare currunt' reflects the popular wisdom, in the longing for reconciliation with one's destiny, by which our deceased merchant was inspired.

3. The adjective 'complures', which here refers to 'terrae', is rarely documented in poetry: mostly in comedy, once in Hor. Sat. 1.10.87, and twice in the pseudo-Vergilian Ciris, II. 54 and 391. On the other hand, it is well documented in prose, especially in reference to places; this usage must therefore derive from the vernacular, very likely that spoken by the merchant himself, rather than from literature.

Juxtaposed in contrast to 'terrae complures', and denoted by the demonstrative 'hic', 'terminus' here is used metonymically: it simultaneously signifies the end of the merchant's life, the abstract object of the Parcae's song, and the physical place of his tomb. This metonymy reflects the conceptual identification of monuments to spatial limitation, like boundary stones, with temporal limits, so that the tomb comes to represent the 'end' of life. This explains the usage of such a phrase as 'constituere terminum' in two different inscriptions, CIL VI 5215 and CIL X 1336 (= CLE 1894 from Nola), both brief and partially metrical. The phrase must have been drawn from a lost model of high stylistic quality, whether epigraphic or literary in character, which our inscription might also have shared.35

The contrastive juxtaposition of 'terminus' with 'terrae complures', brought to our attention by deictic 'hic', associates death with travel in a foreign country, a connection which sometimes features in funerary inscriptions. The only significance of the place of death lies then in the fact it differs from the place of birth.36 The name and origin of our deceased merchant is unknown, however,37 while the mention at I. 4 of the moment of birth gives no indication of a specific place.

4. The presence of the Parcae reflects a broader epigraphic theme. They usually appear in relation to their role in determining lifespan, and are typically the object of blame, as the cause of an untimely death. Negative attributes therefore predominate, and the image of the Parcae spinning the threads of life is more common by far than that of their role as prophetesses.

Very few inscriptions mention prophecy, yet not without a reproachful or judgemental tone: CLE 1141, 14-16 (= CIL III 2609 from Salona) 'Infelix mater ... / incusat denique Parcas / quae uitam pensant quaeque futura canunt'; CLE 1160, 3 (= CIL III 3146 from Opsorus, Dalmatian island) 'Legem fatis Parcae dixere cruentam'; CLE 55, 12-13 (= CIL VI 10096 and CIL I [2] 1214) 'En hoc in tumulo cinerem nostri corporis / infistae Parcae deposierunt carmine', where one is presented with the extraordinary image of the Parcae burying the deceased with their song. In comparison to these examples, our epitaph differs in its acquiescent acceptance of destiny and focus on the moment of birth rather than of death, suggesting an archaizing deference for the Parcae which surely derives from literary models.38

Although the phrasing is similar, one should reject the influence of Tib. 3.11.3-4 'Te nascente nouum Parcae cecinere puellis / seruitium', since genre and content are quite unrelevant,39 or of Ov. Trist 5.3, 25-26 'Hanc legem nentes fatalia Parcae / stamina bis genito bis cecinere tibi', where the prophecy is about life, not death. One might rather recall Catull. 64.383 'Carmina diuino cecinere e pectore Parcae' and Tib. 1.7.1-2 'Hunc cecinere diem Parcae fatalia nentes / stamina'.

Far more interesting is to observe in our inscription the desinence in 'cecinere' -ere, rather than -erunt, at the end of the verse with no metric convenience. Limitations of space may have posed problems, as I. 4 actually reaches the right edge of the stone. As 'cecinere' replaces 'cecinerunt' in nearly every poetic passage about prophecy until the late antiquity, however, it must have been carefully chosen here in order to evoke the literary tradition.

5-7. The second biographical sequence adds more colour and subjectivity to the narration. Apart from a slightly elevated emotional tone, it recalls polite conversation, featuring commonplaces and the everyday language of the mercantile profession.

5. The adverb 'hic' at the beginning of verse, referring to the tomb, emphasizes the contrast between the conditions of the living and those of the dead.

The phrase 'deponere curas / labores' is recorded in TLL V 1, 578, 72 and 579, 13. The verb means 'to let go', 'to give up', when used in relation to abstract objects. In poetry 'depone la[borem]' occurs in CLE 513, 1 (= CIL XI 627 from Forli) in an address to the wayfarer, while 'deponere curas / - am' is found in Verg. Georg. 4.531 'Nate, licet tristis animo deponere curas', Aen. 12.48-49 'Quam pro me curam geris ... / deponas' and in Ov. Rem. 259 'Nulla recantatas deponent pectora curas', Trist. 4.7.19-20 'Credam / mutatum curam deposuisse mei'. Since all these belong to contexts involving familial emotionality,40 the phrase is likely to come from spoken language. Actually, 'deponere' often occurs in prose in Cicero's and Seneca's letters and dialogues, taking any kind of feeling and disposition as object; in particular, one could compare Cic. Rep. 1.15 'Socratem ... qui omnem eius modi curam deposuerit', Fam. 4.6.2 'Omnes curas doloresque deponerem' and Ad Q. fr. 3.8.1 'Militiae labores ceteraque ... depones'.

On the other hand, the funerary context and the adverb 'hic' pointing out the tomb seem to recall the specific meaning of 'deponere', 'to bury', as if hinting at a variation on the epigraphic formula 'deponere corpus / ossa' or, metonymlcally, 'animam'.

6. 'Mare saeuom' can be traced back to Liv. Andr. Carm. fr. 18.1-2 Blansdorf2 'Nullum peius macerat humanum / quamde mare saeuom'. However, the collocation is attested in a few later authors too, and since the place of this fragment is uncertain, it is not likely that it alludes here to the Odyssey.41 There is indeed an echo of 'magnum mare' at I. 2, which is reproduced here with an elevated tone of menace.

The adjective 'saeuus' usually refers to the natural elements in the elegiac poets, especially Ovid: throughout his works, one might compare 'saeui ... ponti' in Met. 14.439, 'saeuo / ... pelago' in Met. 14.559-60, 'freta saeua' in Trist 5.9.18 and 'saeuo ... mari' in Pont. 4.16.14. Actually, the whole of I. 6 evokes the climactic power of the savage sea typical of epic-tragic imagery, found in Lucretius, Virgil, and in some archaic scenic fragments.42

It is also worth noting the heightened emotionality implied by anaphoric 'hic', emphasized by its position in the middle of the verse, and 'nec', which compounds the metaphorical pressure of its atmospheric imagery.

7. The poem comes at last to address the merchant's financial anxieties. 'Sumptus' and 'quaestus', costs and profit, are intrinsic to commercial life whose appearance in poetry is confined to comedy, satire, and didactic poetry.

In TLL VIII 902, 'metuo' is compared to 'timeo', generally meaning 'to expect damage'. There, the two are virtually synonyms.43 Even though there is no semantic difference, in the case of our epitaph there is indeed a syntactic choice: 'timeo' takes as direct object 'sidera', 'nimbos' and 'mare', which stand for the weather conditions, while 'metuo' governs a subordinate optative clause describing the event of a bad outcome, perfectly fitting the definition in Cic. Tusc. 3.25 'Metus opinio magni mali impendentis'.44

The theme of death bringing an end to the to-and-fro of costs and profit is found in a few other funerary inscriptions. All date to the imperial period, feature comparably similar phrasing, and come mostly from the Transpadane region. The archetype must be the couplet 'Quaerere cessaui numquam, nec perdere desi; / mors interuenit, nunc ab utroque uaco', which is metrically regular and occurs in identical wording in CLE 1091 and 1092 (= CIL V 4656 and 7047, respectively from Brescia and Turin).45 It is difficult, however, to associate this specific phrase with that found in our epitaph.

The subordinative conjunction 'ni', instead of 'ne', is especially attested, but not exclusively so,46 in the most ancient authors: as well as 'hicc' at I. 3, it should be considered an alternative form, rather than an archaism.

8-10. The third biographical sequence conveys in a solemn prayer to Fides the merchant's personal experience with contracts and agreements, ending with general advice to humanity; the language combines dignified ritual formulas with popular wisdom and emotional emphasis. According to ancient tradition, the worship of Fides was instituted by Numa Pompilius; after a period of decadence, it was reinstated in the Augustan age.47

8. 'Alma Fides' at the beginning of the verse is not likely to be a specifically Ennian echo48 (Scaen. 403 Vahlen2 = Trag. 350 Jocelyn 'O Fides alma apta pinnis, et ius iurandum Iouis'): 'almus' is a common adjective in addresses to gods and is, moreover, placed after the noun in this fragment. On the contrary, 'alma' typically precedes the noun elsewhere in later periods, especially in late antiquity; seen alongside our epitaph, Stat. Theb. 11.98 'Licet alma Fides Pietasque repugnent' and Sil. Pun. 6.132 'Alma Fides mentem ... amplexa tenebat' may suggest another lost epic model.

The periphrasis 'ago grates' and the suffix of the superlative -issuma are archaisms deriving from liturgical contexts; in particular 'grates', an alternative form of 'gratias', originally defined specific praises to gods.49 The whole verse has the rhythm of a litany, created by the trithemimeral and hephthemimeral caesuras, and the effect is emphasized by the serial alliteration of fricative, dental, sibilant and vibrant sounds, extending up to I. 10.

9. The collocation 'fortuna infracta'50 occurs in Val. Max. 4.7 pr. 'Infractae fortunae homines magis amicorum studia desiderant uel praesidiis uel solaciis gratia', whereas the same noun and verb are combined differently in Publil. Sent. fr. 24 'Fortuna uitrea est: tum cum splendet frangitur' and CLE 1336, 9 (= ICVR VII 18446, 4th century AD) 'Frangitur explicitis tristis fortuna querellis'. These have the feel of proverbial wisdom, which is the likely source of the phrase in our epitaph as well.

The adjective 'fessus' attached to the first-person singular pronoun has a particularly emotive feel in poetry, referring to various kinds of weariness. In Verg. Aen. 3.710-1 'Hic me, pater optime, fessum / deseris' Aeneas mourns his father; in Hor. Sat. 1.6.125-6 'Ast ubi me fessum sol acrior ire lauatum / admonuit' the poet contrasts a lazy morning start with the business of a public life; in Prop. 4.9.42 (= 66)51 'Fesso uix mihi terra patet' the suppliant Cacus cries for a little water.

A sign of emotional emphasis is also to be noticed in the second-person singular pronoun at the beginning of I. 10, as well as in the spondaic rhythm of both verses.

10. The plural adjective 'mortales' is here substantivized as a lofty synonym of 'homines'. For 'opto', one should compare CLE 2 (= CIL XI 3078 and CIL 1 [2] 364, from Civita Castellana, in the Fallscan territory), which is largely regarded as partially metrical,52 and dating to no later than the second half of the 2nd century BC. It is a votive lamina recording a college of cooks seeking to gain favour with the divine triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. 'Vtei sesed lubent[es be]ne iouent optantis' (I. 6, the last). It features linguistic phenomena from the Republican age as well as dialectal forms, commercial vocabulary and references to Plautus, alongside a taste for tautology; in the awkward attempt to create a lofty style, colloquialisms and archaisms are combined and often hard to distinguish from one another. The closing formula, in the metre of a regular Saturnian verse, must have been common in dedications.53 In both our inscription and in CLE 2, even if not recorded in TLL IX 2, 833, 5, the usage of 'opto' seems to pertain to the specific meaning 'to pray', rather than the more common 'to want, wish': in effect, it denotes the desire to want or wish a divinity for oneself, and thus to pray to them, in order to gain their favour.

11-12. We come to the final appeal to the wayfarer with thanks and greetings. A contrast may be drawn between the opening vocative 'hospes', and the earlier invocation of 'alma Fides': the tone shifts to that of conventional familiarity, but this is couched in original phrasing, and a hint of sanctity in its closure. Assonance and alliteration convey a sympathetic feel.

11. As a wish for good health, the alliterative collocation in asyndeton 'uiue uale' Is in fact little attested in epigraphy: it only occurs in CLE 1299, 1 (= CIL VI 24800), CLE 1431, 13 (= ICVR VII 19255) and in ZPE 201, p. 74, I. 11 (from Cartagena in Spain, of the Augustan age) where the whole hemistich is identical. Both verbs are far more frequently found in inscriptions either alone or conjoined, in different inflections, rather than simply juxtaposed.54 On the other hand, the collocation seems to be a literary usage. and is especially found in comedy.55 Additionally, it is found in Lucr. 5.961 'Quisque ualere et uiuere doctus'; in Catull. 11.17 'Cum suis uiuat ualeatque moechis'; in Hor. Sat. 2.5.110 'Imperiosa trahit Proserpina: uiue ualeque' and Epist. 1.6.67 'Viue, uale'; the phrase never appears, however, in Cicero's or Seneca's letters. As in the case of 'magnum mare' at I. 2, the assonance probably derives from the spoken language.

Moreover, 'in sumptum superet tibi semper' is not only an unusual impersonal construction, but is also unprecedented as a practical wish for affluence. It is nonetheless particularly appropriate to our epitaph's values, which it emphasizes by the serial alliteration of sibilant, labial and dental sounds. The closest comparison would be with 'bene rem geras': it is attested in Plaut. Cas. 87 'Tantum est. Valete, bene rem gerite' and Mil. 936 'Bene ambula, bene rem geras'; in Hor. Epist. 1.8.1 'Celso gaudere et bene rem gerere Albinouano'; in CLE 11, 5 (= CIL VI 13696 and CIL I [2] 1202). The last two contexts suggest special politeness.56

12. Paying respect to the grave is an ordinary theme in funerary inscriptions; the closure 'dignum dicasti' seems however to add some ambiguity. Our passage is recorded in TLL IV 965, 39-40 under the specific meaning of 'dico', 'to designate, sanction', which gives it a sacral, ritual feel. One should also consider the broader sense of 'proclaim, announce' as well, since its etymology has relevance: in some verbs distinguished by prosodic vowel gradation, as indeed dico-dico or Iabor-Iabo, the form with long vowel likely stands for an ancient root of aorist, while the other form with the suffix -a of the first conjugation features an intensive-durative aspect.57 The wayfarer's dedication is therefore not intended as a mere momentary act, in which the grave is sanctified; rather, in the very accumulation of speech-acts by multiple other wayfarers stopping to read the epitaph, the deceased's memory lives on in perpetuity, thereby enhancing its quality as a monument.58

In conclusion, our epitaph is remarkable at a literary level, in both structure and content; it displays competence in versification, awareness of the epigraphic tradition, and creativity. The presence of quotations, or at least the ones we can recognize, shows that the composer had mastered older texts central to Latin cultural identity and its idealization of the past.59 But one can also find references to more recent classics: Horace in particular, but also Lucretius, Virgil, and Ovid. In style and language, elevated and commonplace phrases are skilfully intertwined alongside liturgical and commercial vocabulary.

The epitaph is also remarkable when compared to other inscriptions of Roman Apulia.60 This observation sharpens the mystery around the identities of both the deceased, whose name and age are missing, and dedicator; even though this information must have been included in some other part of the funeral monument, the complete absence of family members or social relations in such a long and structured composition is striking. It is not unlikely that the merchant himself had commissioned the work for some 'mercenary poet', a figure which became increasingly popular with the decline of patronage; one is surprised to find the poetic composer empathizing with the client's experiences and values. It is unclear whether local teachers were able to provide an education of the sort, or whether this was rather to be sought at the capital. It is further uncertain where the inscription was actually erected; a location at Brindisi is more dubious if we remember that the stone was recovered from the port, and thus possibly in the context of a shipwreck: If so, the problem remains insoluble.

Fig. CIL IX 60 = 1533 (Silvestrini [1987]) CIL = vei s[9n

_______________

Notes:

1 Unless otherwise stated, translations are to be considered mine.

2 For these usages of interpuncta, cf. Massaro (2018) 51 and Massaro (2013a) 391-3.

3 As reported in CIL IX 60 and stated in Henzen (1872) 31. Cugusi (2004) 133-4, in a brief reference to the inscription, restricts the date to the beginning of the 2nd century AD, claiming that palaeographic aspects suggest so; giving the same reason, though, Silvestrini (chapter IV in Grelle [2017] 194) reports the date as in CIL IX 60, and so she does in Epigrpahic Database Rome (EDR167254, record written in May 2018).

4 For other details surrounding the inscription's materiality and lettering, cf. Tise (2001).

5 See above, though, about the interpunctum at the end of I. 1.

6. The only exception is v.5, where meas must be considered monosyllabic; see below.

7 CF. TLL VI, 2965, 49-84).

8 Priscian says so about Aen. 2.664 'Hocc erat alma parens' (2.952, 22 Keil); this is reported too in Ribbeck (1866) 214 and 425.

9 Especially Velius Longus 7.54.6-14 Keil.

10 Cf. Leumann (1977) 468 and Tronskij (1953) 167. 11 Cf. TLL VIII 915, 48. Metrical convenience and the influence of oral pronunciation seem to be the reasons for this phenomenon; cf. also Timpanaro (1988) 878-9; Ceccarelli (1997) 388-94; Questa (2007) 173-80.

12 It is also the most ancient, being attested in several inscriptions from the Republican period: e.g. CLE 73, 1 (= CIL IX 1527, from near Beneuentum) 'Hospes resiste et quae sum in monumento lege'; CLE 74, 1 (= CIL VI 9545 and CIL I [2] 1212) 'Hospes resiste et hoc ad grumum ad laevam aspice'; CLE 118, 1 (= CIL X 5371, from Interamna Lirenas, in Campanie) 'Hospes resiste et nisi molestust perlege'. Cf. Morelli (2018) 115.

13 E.G. CLE 1007, 1 (= CIL XIII 7070, from Mainz) 'Praeteriens quicumque legis, consiste uiator'; AE 1996, 453, 1 (from Luceria) 'Sic iter hoc felix tibi sit, consiste (u(i)ator'; CLEPann 44, 1 (from Gorsium) 'Tu qui festinas pedibus, consiste uiator'.

14 The collocation is not unusual: 'hospes' and 'consiste' occur together elsewhere, both in iambic and dactylic rhythm, either juxtaposed or with the verb at some distance; e.g. CLE 980, 1 (= CIL I [2] 3449d, from Carthago Nova) 'Hospes consiste et Thoracis periege nomen'; AE 2008, 403, 3-4 (from Venafrum, in prose or metric cola) 'Hospes qui legis hoc mo[n]/umentum consiste et perieg[3]'. Cf. Massara (2019), 50-51.

15. Cf. Hofmann (2003) 290, 380.

16 Plaut Epid. 461 'Si tibi molestum non est', anywhere else (Most. 856, Persa 599, Poen. 50, Rud. 120, Trin. 932) 'Nisi molestumst'; Ter. Ad. 806 'Nisi molestumst'; Afran. Com. 95 Ribbeck3 (= 80 Daviault) 'Nisi molestum est'.

17 Indirect tradition in Non. p. 143, 33, where the passage is mentioned about 'noenu[m] pro non'.

18 Mostly (Acad. 1.4, Cato 6, Cluent. 150 and 168, Fin. 1.28 and 2.5, Nat. D. 1.17, Planc. 5, Rep. 1.46, Tusc. 1.26) 'Nisi molestum est', elsewhere (Fam. 5.12, 10, Fat. 4, Nat.D. 1.99) 'Si tibi non est molestum'.

19 30.17.11 'Nisi molestum esset' and 45.13.17 'Nisi molestum sit'.

20 Later it only occurs in Flor. Verg. 1.2 'Nisi molestum est' and Hist. Apoll. rec. A et B 15 'Si (tibi A, uero B) molestum non est'. Cf. TLL VIII 1354, 15-25.

21 Cf. Morelli (2018) 116 n. 27.

22 Cf. also CLE 1537a, 2 (= CIL VI 25703) 'Si graue non animost, fata... acerba leges' (also integrated in CLE 2083, 2, from Lanuuium) and CLEAfr II 233, 2 (from Cesarea) 'Si non forte grav(e) est, d[isce]'.

23 Indirection tradition in Macr. Sat. 6.5.10, where the passage is mentioned as the model for Verg. Aen 1.224.

24 Only attested in Ennius, in the ablative plural 'ueliuolantibus / nauibus' (Scaen. 67-68 Vahlen2 = Trag. 45-46 Jocelyn).

25 This passage too is mentioned by Macrobius in the context referred to above; Muller adds 'carina' after 'maria alta', Ribbeck turns 'Laueius' into 'Liuius'.

26 Cf. Massaro (1983) 201-2 n. 19.

27 Cf. Ronconi (1971) 11-86.

28 In Enn. Ann. 445 Vahlen2 (= 434 Skutsch) and Scaen. 65 Vahlen2 (= Trag. 50 Ribbeck3); in Lucr. 2.1, 3.1029, 6.144, and 6.505; in Verg. Aen. 5.628.

29 Cf. Caviglia (1984) 11; such a connection seems unlikely at both a linguistic and a conceptual level.

30 Cf. Franzoi (2004) 258.

31 Cf. Cugusi (1985) 214-6.

32 Cf. TLL IV 1512, 72.

33 These are the merchants themselves, as one gathers from the context.

34 Cf. Caviglia (1984) 11.

35 Cf. Massaro (2006) 24-26.

36 Cf. Cugusi (1985) 200-1, 221.

37 Cf. Silvestrini (1998) 230.

38 Cf. Colafrancesco (2004) 139-76, 180-1; Massaro (1992) 171-2

39 Cf. Popova (1967) 161 and (1976) 41: a few years after proposing a Tibullian model for our passage, the scholar herself seems rather to recognize a Horatian model. As she writes in (1967) 171, it is impossible to decide who influence whom when different authors share themes or loci communes, but in this case the assumption of primarily lexical similarity does not seem tenable.

40 In Verg. Georg. 4.531 Cyrene comforts her son Aristaeus; in Aen. 12.48-49 Turnus bids farewell to his father-in-law, the king of the Latins, before going to die in battle; in Ov. Rem. 259 the subject is love; in Trist. 4.7.20 the object of affection is the poet's pen friend, whom he calls 'carissime'.

41 Cf. above, commentary on I. 2.

42 Cf. Caviglia (1984) 11 n.18.

43 Cf. TLL VIII 901, 59.

44 Cf. TLLVIII 907, 21-22.

45 Cf. Polverini (1976).

46 E.g. Lucr. 2.734 (niue); Catull. 61.153; Prop. 2.7.3; Verg. Aen. 3.686 and CLE 2068, 7 (= CIL XI 7856, from Carsulae, mid-1st century AD).

47 Cf. Freyburger (1986) and Otto (1909).

48 Cf. Caviglia (1984) 11 n. 18; Franzoi (2004) 259; even Bucheler takes it as such.

49 Cf. TLL VI 2, 2204, 11-12 and 16; Ernout/Meillet 19594, s.v. 'gratus', 281-2.

50 Cf. TLL VII 1, 1494, 3 and 70.

51 Editors place II. 65-66 between II. 42-43, while the authenticity of I. 42 is suspect.

52 Although once seen as a composition in highly irregular 5aturnian verses, it should rather be recognized as a lofty prose work with generic metric tendencies; cf. Massaro (2007) 128-9 and Kruschwitz (2002) 127-38.

53 Cf. Peruzzi (1966) and Stolz et al. (1973[3]) 43-45.

54 Cf. CLE 973, 10 (= CIL VI 21200) 'ulue hospes dum licet atque uale', AE 1969/70, 568, 8-9 'ualeat uiator / uibat q ui leget ', AE 2006, 475, 8 'ualete ad superos uiuite uita(m) optima(m)'.

55 E.g. Plaut. Mil. 1340 'Conserui conseruaeque omnes, bene ualete et uiuite', Stich. 31 'Quom ipsi interea uiuant, ualeant ', Trin. 996 'Male uiue et uale!' and Ter. Andr. 890 'Immo habeat, ualeat, uiuat'.

56 Cf. Massaro (1992) 75-76.

57 Cf. Vendryes (1910) 303 and Ernout/Meillet (1959 [4]) s.v. 'dico', 173.

58 Cf. Franzoi (2004) 260-2.

59 Cf. Gianotti (1989) and Pugliarello (2011).

60 Metric inscriptions of Apulia and Calabria are collected in Silvestrini (1996) 451; no other finds are recorded in the following issues of AE.