by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/1/20

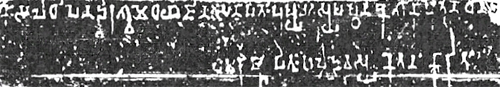

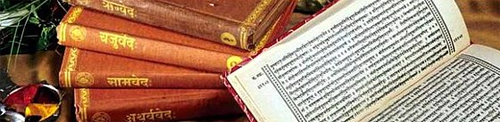

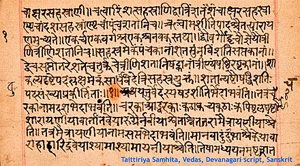

By this time, other manuscripts of the Vedas had been obtained in India. In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão. A doctor named Pedro da Silva Leitão had been present at the court of Jai Singh in 1728 and played a part in the negotiations with the Portuguese regarding the exchange of scientific knowledge, personnel, and equipment. He was long-lived, but Polier’s friend may rather have been one of his descendants. Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the saṃhitās of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century….

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, w.ch are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

--The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

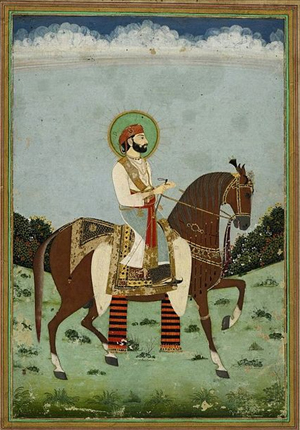

Jai Singh II, Maharajah Sawai

Reign: 1699–1743

Predecessor: Bishan Singh

Successor: Ishvari Singh

Born: Vijay Singh, 3 November 1688, Amer, India

Died: 21 September 1743 (aged 54)

Spouse: Ranawat; Surya Kumari; Gendi

Issue: Kunwar Shiv Singh (d. 1724); Kunwar Ishwari Singh; Kunwar Madho Singh

Father: Bishan Singh

Mother: Indar Kanwar of Kharwa[1]

Religion: Hinduism

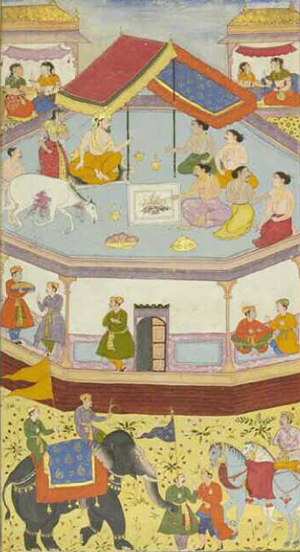

Jai Singh II (3 November 1688 – 21 September 1743) was the Hindu Rajput ruler of the kingdom of Amber, he later founded the fortified city of Jaipur and made it his capital. He was born at Amber, the capital of the Kachwahas. He became ruler of Amber at the age of 11 after his father Maharaja Bishan Singh died on 31 December 1699.[2]

Initially, Jai Singh served as a Mughal vassal. He was given title of Sawai by the Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb in the year 1699, who had summoned him to Delhi, impressed by his wit.[3] On 21 April 1721, the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah bestowed upon him the title of Saramad-i-Rajaha-i-Hind and on 2 June 1723, the emperor further bestowed him the titles of Raj Rajeshvar, Shri shantanu ji and Maharaja Sawai (which he personally sought from the Mughal emperor by means of various officials and gifts).[4] "Sawai" means one and a quarter times superior to his contemporaries.[5]

In the later part of his life, Jai Singh broke free from the Mughal hegemony, and to assert his sovereignty, performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, an ancient rite that had been abandoned for several centuries.[6][7] He moved his kingdom's capital from Amber to the newly-established city of Jaipur in 1727, and performed two Ashvamedha sacrifices, once in 1734, and again in 1741.[8]

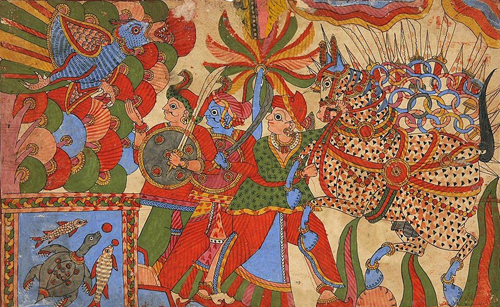

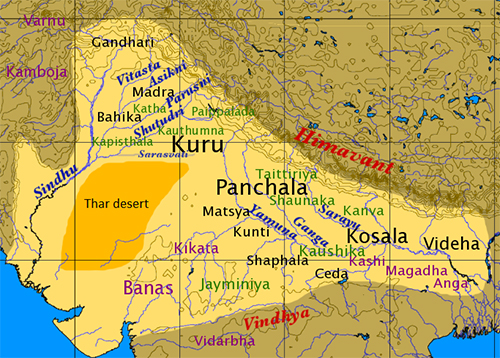

The Ashvamedha (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध aśvamedha) is a horse sacrifice ritual followed by the Śrauta tradition of Vedic religion. It was used by ancient Indian kings to prove their imperial sovereignty: a horse accompanied by the king's warriors would be released to wander for a period of one year. In the territory traversed by the horse, any rival could dispute the king's authority by challenging the warriors accompanying it. After one year, if no enemy had managed to kill or capture the horse, the animal would be guided back to the king's capital. It would be then sacrificed, and the king would be declared as an undisputed sovereign.

The best-known text describing the sacrifice is the Ashvamedhika Parva (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध पर्व), or the "Book of Horse Sacrifice," the fourteenth of eighteen books of the Indian epic poem Mahabharata. Krishna and Vyasa advise King Yudhishthira to perform the sacrifice, which is described at great length. The book traditionally comprises 2 sections and 96 chapters. The critical edition has one sub-book and 92 chapters.

The ritual is recorded as being held by many ancient rulers, but apparently only by two in the last thousand years. The most recent ritual was in 1741, the second one held by Maharajah Jai Singh II of Jaipur. The original Vedic religion had evidently included many animal sacrifices, as had the various folk religions of India. Brahminical Hinduism had evolved opposing animal sacrifices, which have not been the norm in most forms of Hinduism for many centuries. The great prestige and political role of the Ashvamedha perhaps kept it alive for longer.

The Ashvamedha could only be conducted by a powerful victorious king (rājā). Its object was the acquisition of power and glory, the sovereignty over neighbouring provinces, seeking progeny and general prosperity of the kingdom. It was enormously expensive, requiring the participation of hundreds of individuals, many with specialized skills, and hundreds of animals, and involving many precisely prescribed rituals at every stage.

The horse to be sacrificed must be a white stallion with black spots. The preparations included the construction of a special "sacrificial house" and a fire altar. Before the horse began its travels, at a moment chosen by astrologers, there was a ceremony and small sacrifice in the house, after which the king had to spend the night with the queen, but avoiding sex.

The next day the horse was consecrated with more rituals, tethered to a post, and addressed as a god. It was sprinkled with water, and the Adhvaryu, the priest and the sacrificer whispered mantras into its ear. A black dog was killed, then passed under the horse, and dragged to the river from which the water sprinkled on the horse had come. The horse was then set loose towards the north-east, to roam around wherever it chose, for the period of one year, or half a year, according to some commentators. The horse was associated with the Sun, and its yearly course. If the horse wandered into neighbouring provinces hostile to the sacrificer, they were to be subjugated. The wandering horse was attended by a herd of a hundred geldings [castrated horse, or donkey or mule], and one or four hundred young kshatriya men, sons of princes or high court officials, charged with guarding the horse from all dangers and inconvenience, but never impeding or driving it. During the absence of the horse, an uninterrupted series of ceremonies was performed in the sacrificer's home.

After the return of the horse, more ceremonies were performed for a month before the main sacrifice. The king was ritually purified, and the horse was yoked to a gilded chariot, together with three other horses, and Rigveda (RV) 1.6.1,2 (YajurVeda (YV) VSM 23.5,6) was recited. The horse was then driven into water and bathed. After this, it was anointed with ghee by the chief queen and two other royal consorts. The chief queen anointed the fore-quarters, and the others the barrel and the hind-quarters. They also embellished the horse's head, neck, and tail with golden ornaments. After this, the horse, a hornless he-goat, and a wild ox (go-mrga, Bos gaurus) were bound to sacrificial stakes near the fire, and seventeen other animals were attached to the horse. A great number of animals, both tame and wild, were tied to other stakes, according to one commentator, 609 in total. The sacrificer offered the horse the remains of the night's oblation of grain. The horse was then suffocated to death.

The chief queen ritually called on the king's fellow wives for pity. The queens walked around the dead horse reciting mantras. The chief queen then had to spend a night with the dead horse.

On the next morning, the priests raised the queen from the place. One priest cut the horse along the "knife-paths" while other priests started reciting the verses of Vedas, seeking healing and regeneration for the horse.

The Laws of Manu refer to the Ashvamedha (V.53): "The man who offers a horse-sacrifice every day for a hundred years, and the man who does not eat meat, the two of them reap the same fruit of good deeds."...

In the Arya Samaj reform movement of Dayananda Sarasvati, the Ashvamedha is considered an allegory or a ritual to get connected to the "inner Sun" (Prana) According to Dayananda, no horse was actually to be slaughtered in the ritual as per the Yajurveda. Following Dayananda, the Arya Samaj disputes the very existence of the pre-Vedantic ritual; thus Swami Satya Prakash Saraswati claims thatthe word in the sense of the Horse Sacrifice does not occur in the Samhitas [...] In the terms of cosmic analogy, ashva s the Sun. In respect to the adhyatma paksha, the Prajapati-Agni, or the Purusha, the Creator, is the Ashva; He is the same as the Varuna, the Most Supreme. The word medha stands for homage; it later on became synonymous with oblations in rituology, since oblations are offered, dedicated to the one whom we pay homage. The word deteriorated further when it came to mean 'slaughter' or 'sacrifice'.

He argues that the animals listed as sacrificial victims are just as symbolic as the list of human victims listed in the Purushamedha. (which is generally accepted as a purely symbolic sacrifice already in Rigvedic times).

All World Gayatri Pariwar since 1991 has organized performances of a "modern version" of the Ashvamedha where a statue is used in place of a real horse, according to Hinduism Today with a million participants in Chitrakoot, Madhya Pradesh on April 16 to 20, 1994. Such modern performances are sattvika Yajnas where the animal is worshipped without killing it, the religious motivation being prayer for overcoming enemies, the facilitation of child welfare and development, and clearance of debt, entirely within the allegorical interpretation of the ritual, and with no actual sacrifice of any animal.

The earliest recorded criticism of the ritual comes from the Cārvāka, an atheistic school of Indian philosophy that assumed various forms of philosophical skepticism and religious indifference. A quotation of the Cārvāka from Madhavacharya's Sarva-Darsana-Sangraha states: "The three authors of the Vedas were buffoons, knaves, and demons. All the well-known formulae of the pandits, jarphari, turphari, etc. and all the obscene rites for the queen commanded in Aswamedha, these were invented by buffoons, and so all the various kinds of presents to the priests, while the eating of flesh was similarly commanded by night-prowling demons."

According to some writers, ashvamedha is a forbidden rite for Kaliyuga, the current age.

This part of the ritual offended the Dalit reformer and framer of the Indian constitution B. R. Ambedkar and is frequently mentioned in his writings as an example of the perceived degradation of Brahmanical culture.

While others such has Manohar L. Varadpande, praised the ritual as "social occasions of great magnitude". Rick F. Talbott writes that "Mircea Eliade treated the Ashvamedha as a rite having a cosmogonic structure which both regenerated the entire cosmos and reestablished every social order during its performance."

-- Ashvamedha, by Wikipedia

Jai Singh had a great interest in mathematics, architecture and astronomy. He commissioned the Jantar Mantar observatories at multiple places in India, including his capital Jaipur.[9]

The situation on his accession

When Sawai Jai Singh acceded to the ancestral throne at Amber, he had barely enough resources to pay for the support of 1000 cavalry—this abysmal situation had arisen in the past 96 years, coinciding with the reign of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. The Jaipur kings had always preferred diplomacy to arms in their dealings with the Mughals, since their kingdom was located so close to the Mughal power centers of Delhi and Agra. Under Aurangzeb, successive Kachawaha Rajas from the time of Ramsingh I were actually deprived of their rank and pay despite years of close alliance with the Emperors of Delhi. Two of their chiefs, Jai Singh I and Kunwar Kishan Singh, died in mysterious circumstances while campaigning in the Deccan.

Six months after his accession, Jai was ordered by Aurangzeb to serve in his ruinous Deccan Wars. But there was a delay of about one year in his responding to the call. One of the reason for this was that he was ordered to recruit a large force, in excess of the contingent required by his mansab. He also had to conclude his marriage with the daughter of Udit Singh, the nephew of Raja Uttam Ram Gaur of Sheopur in March, 1701. Jai Singh reached Burhanpur on 3 August 1701 but he could not proceed further due to heavy rains. On 13 September 1701 an additional cut in his rank (by 500) and pay was made.[10] His feat of arms at the siege of Khelna (1702) was rewarded by the mere restoration of his earlier rank and the title of Sawai (Sawai-meaning one and a quarter, i.e. more capable than one man). When Aurangzeb's grandson Bidar Bakht deputed Sawai Jai Singh to govern the province of Malwa (1704), Aurangzeb angrily revoked this appointment as jaiz nist (invalid or opposed to Islam).

Dealings with the later Mughals

The death of Aurangzeb (1707) at first only increased Jai Singh's troubles. His patrons Bidar Bakht and his father Azam were on the losing side in the Mughal war of succession—the victorious Bahadur Shah continued Aurangzeb's hostile and bigoted policy towards the Rajputs by attempting to occupy their lands. Sawai Jai Singh formed an alliance with the Rajput states of Mewar (matrimonially) and Marwar, which were done to form an alliance against Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah I. Aurangzeb's rule of excluding Rajputs from the administration was now abandoned by the later–Mughals and Bahadur Shah appointed Jai Singh to govern the important provinces of Agra and Malwa. In Agra he came into conflict with the sturdy Jat peasantry.

Attack on Sardar Churaman

While Aurangzeb was sinking deeper into the morass of his Deccan Wars, the Jats overthrew the Mughal administration in Agra province. Sawai Raja Jai Singh received large funds from the Mughal courts and with the support of Bhim Singh Hada, of Kotah, Gaj Raj Singh of Narwar, and Budh Singh Hada of Bundi, besieged the fort of Thun in 1716. Churaman's nephew Thakur Badan Singh came over to Jai Singh and provided him with vital information on the weak points of Thun. After its conquest Jai Singh captured and demolished other smaller forts and dispersed the Jat confederacies for a short period.

Sawai Jai Singh and the Marathas

The Kachwaha ruler was appointed to govern Malwa three times between 1714 and 1737. In Jai Singh's first viceroyalty (subahdar) of Malwa (1714–1717), isolated Maratha war-bands that entered the province from the south (Deccan) were constantly defeated and repulsed by Jai Singh. In 1728, Peshwa Baji Rao defeated the Nizam of Hyderabad, part of the Mughal Deccan (treaty of Sheogaon, February 1728). With an agreement from Baji Rao to spare the Nizam's own domains, the Nizam allowed the Marathas a free passage through Berar and Khandesh, the gateway into Hindustan. The Marathas were then able to plant a permanent camp beyond the southern frontier of Malwa. Following the victory of the Peshwa’s brother, Chimaji Appa, over the governor of Malwa Girdhar Bahadur on 29 November 1728, the Marathas were able to convulse much of the country beyond the Southern borders of the Narmada.

Upon Sawai Jai Singh's second appointment to Malwa (1729–1730), as a far-sighted statesmen, Jai Singh was able to perceive a complete change in the political situation, during the twelve years which had passed since his first viceroyalty there. Imperial power had by then been crippled by the rebellion of the Nizam of Hyderabad as well as the ability of Peshwa Baji Rao to stabilize the internal situation of the Marathas, which resulted in their occupation of Gujarat and an immense increase of their forces. Nonetheless, in the name of the friendship between their royal ancestors, Sawai Jai Singh II, was able to appeal to Shahu to restore to the imperialist, the great fortress of Mandu which the Marathas had occupied a few weeks earlier (order date 19 March 1730). By May, Jai Singh was recalled back to Rajputana to attend more pressing matters, which thus resulted in his two years disassociation from Malwa.

In 1732, Jai Singh was for the last time, appointed Subahdar of Malwa (1732–1737), during which time he advocated Muhammad Shah, to compromise with the Marathas under Shahu, whom greatly remembered the kindness and relationship between the late Mirza Raja (Jai Singh I) and his own grandfather, Shivaji. For this sensible advice, coupled with anti-Jai Singh rhetoric at the Mughal court at Delhi, as well as Muhammad Shah's inability to assert his own will, Jai Singh was removed from his post while the Mughals decided on war. In this regard, Sawai Jai Singh II was practically the last subahdar of Malwa, as Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, who replaced him in 1737, met with most discomfiting failure at the hands of the Peshwa, resulting with the ceding of the whole of Malwa to the Marathas (Treaty of Duraha, Saturday 7 January 1738).

Exploiting the weakening of the Mughal state, the Persian raider Nadir Shah defeated the Mughals at Karnal (13 February 1739) and finally sacked Delhi (11 March, same year). Through this period of turmoil Jai Singh remained in his own state—but he was not idle. Foreseeing the troubled time ahead, Sawai Jai Singh II, initiated a program of extensive fortification within the thikanas under Jaipur, to this date, most of the later fortifications abound the former Jaipur state, are attributed to the reign of Sawai Jai Singh II.

Sawai Jai Singh’s armed forces and his ambitions in Rajputana

Jai Singh increased the size of his ancestral kingdom by annexing lands from the Mughals and rebel chieftains—sometimes by paying money and sometimes through war. The most substantial acquisition was of Shekhawati, which also gave Jai Singh the most able recruits for his fast expanding army.[11]

According to an estimate by Jadunath Sarkar; Jai Singh's regular army did not exceed 40,000 men, which would have cost about 60 lakhs a year, but his strength lay in the large number of artillery and copious supply of munitions which he was careful to maintain and his rule of arming his foot with matchlocks instead of the traditional Rajput sword and shield - He had the wisdom to recognize early the change which firearms had introduced in Indian warfare and to prepare for himself for the new war by raising the fire-power of his army to the maximum, he thus anticipated the success of later Indian rulers like Mirza Najaf Khan, Mahadji Sindhia and Tipu Sultan. Sawai Jai Singh's experimental weapon, the Jaivana which he created prior to the shift of his capital to Jaipur, remains the largest wheeled cannon in the world. In 1732, Sawai Jai Singh, as governor of Malwa undertook, to maintain 30,000 soldiers, in equal proportions of horsemen and foot-musketeers. These did not include his contingents in the Subahs of Agra and Ajmer and in his own dominions and fort garrisons.

The armed strength of Jai Singh had always made him, the most formidable ruler in Northern India and all the other Rajas looked up to him for protection and the promotion of their interests at the Imperial court. The fast-spreading Maratha dominion and their raids into the north had caused alarm among the Rajput chiefs—Jai Singh called a conference of Rajput rulers at Hurda (1734) to deal with this peril but nothing came of this meeting. In 1736 Peshwa Baji Rao imposed tribute on the Kingdom of Mewar. To thwart further Maratha domination Sawai Jai Singh planned a local hegemony, to form under the leadership of Jaipur, a political union in Rajputana. He first annexed Bundi and Rampura in the Malwa plateau, made a matrimonial alliance with Mewar, and intervened in the affairs of the Rathors of Bikaner and Jodhpur. These half-successful attempts only stiffened the backs of the other Rajput clans who turned to the very same Marathas for aid, and consequently hastened their domination over Rajasthan. Jai Singh's ambitions in Rajputana failed after the Battle of Gangwana, Gangwana was the last battle fought by Jai Singh as he could never recover from the shock and died two years later in 1743. Madho Singh later avenged his father by poisoning Bhakt Singh. (Jai Singh was cremated at the Royal Crematorium at Gaitore in the north of Jaipur) he was succeeded by his less capable son Ishwari Singh.[12]

Contributions to society, culture, and science

Sawai Jai Singh was the first Hindu ruler in centuries to perform the ancient Vedic ceremonies like the Ashwamedha (1716)[13] sacrifices — and the Vajapeya (1734) on both occasions vast amounts were distributed in charity. Being initiated in the Nimbarka Sampradaya of the Vaishnava religion, he also promoted Sanskrit learning and initiated reforms in Hindu society like the abolition of Sati and curbing the wasteful expenditures in Rajput weddings. It was at Jai Singh's insistence that the hated jaziya tax, imposed on the Hindu population by Aurangzeb (1679), was finally abolished by the Emperor Muhammad Shah in 1720. In 1728 Jai Singh prevailed on him to also withdraw the pilgrimage tax on Hindus at Gaya.

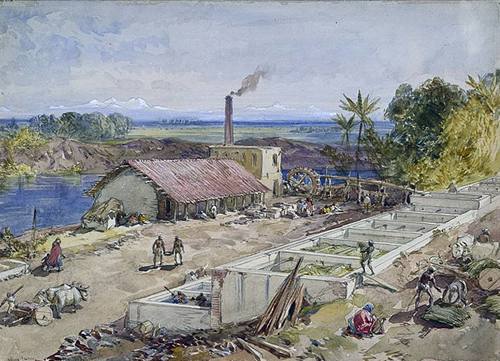

In 1719, he was witness to a noisy discussion in the court of Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah. The heated debate regarded how to make astronomical calculations to determine an auspicious date when the emperor could start a journey. This discussion led Jai Singh to think that the nation needed to be educated on the subject of astronomy. It is surprising that in the midst of local wars, foreign invasions, and consequent turmoil, Sawai Jai Singh found time and energy to build astronomical observatories.

The observatory built by Sawai Jai Singh in Delhi

Five observatories were built at Delhi, Mathura (in his Agra province), Benares, Ujjain (capital of his Malwa province), and his own capital of Jaipur. His astronomical observations were remarkably accurate. He drew up a set of tables, entitled Zij Muhammadshahi, to enable people to make astronomical observations. He had Euclid's "Elements of Geometry" translated into Sanskrit as also several works on trigonometry, and Napier's work on the construction and use of logarithms.[14] Relying primarily on Indian astronomy, these buildings were used to accurately predict eclipses and other astronomical events. The observational techniques and instruments used in his observatories were also superior to those used by the European Jesuit astronomers he invited to his observatories.[15][16] Termed as the Jantar Mantar they consisted of the Ram Yantra (a cylindrical building with an open top and a pillar in its center), the Jai Prakash (a concave hemisphere), the Samrat Yantra (a huge equinoctial dial), the Digamsha Yantra (a pillar surrounded by two circular walls), and the Narivalaya Yantra (a cylindrical dial).

Jantar Mantar in Varanasi

The Samrat Yantra is a huge sundial. It can be used to estimate the local time, to locate the Pole Star, and to measure the declination of celestial objects. The Rama Yantra can be used to measure the altitude and azimuth of celestial objects. The Shanku Yantra can be used to measure the latitude of the place.[14]

Jai Singh's greatest achievement was the construction of Jaipur city (known originally as Jainagara[citation needed] (in Sanskrit, as the 'city of victory' and later as the 'pink city' by the British by the early 20th century), the planned city, later became the capital as the Indian state of Rajasthan. Construction of the new capital began as early as 1725 although it was in 1727 that the foundation stone was ceremonially laid, and by 1733 Jaipur officially replaced Amber as the capital of the Kachawahas. Built on the ancient Hindu grid pattern, found in the archaeological ruins of 3000 BCE, it was designed by Vidyadhar Bhattacharya who was educated in the ancient Sanskrit manuals (silpa-sutras) on city-planning and architecture. Merchants from all over India settled down in the relative safety of this rich city, protected by thick walls, and a garrison of 17,000 supported by adequate artillery. A Sanskrit epic by the name 'Ishvar Vilas Mahakavya' written by Kavikalanidhi Devarshi Shrikrishna Bhatt gives a good historical description of various important events of that era, including the construction of Jaipur city.[17]

Jai Singh also translated works by people like John Napier. For these multiple achievements, Sawai Jai Singh II is remembered as the most enlightened king of 18th-century India even to this date. These days Jai Singh's observatories at Jaipur, Varanasi, and Ujjain are functional. Only the one at Delhi is not functional and the one at Mathura disappeared a long time ago. [18]

See also

• House of Kachwaha

• List of Rajputs

References

1. Harnath Singh, Jaipur and its Environs (1970), p.9

2. Andrew Topsfield (2000). Court Painting in Rajasthan. Marg. p. 50. ISBN 978-81-85026-47-3.

3. Sarkar, Jadunath (1984, reprint 1994) A History of Jaipur, New Delhi: Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-0333-9, p.171

4. Sarkar, Jadunath (1984, reprint 1994) A History of Jaipur, New Delhi: Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-0333-9, p.171

5. Prahlad Singh; Kalyan Dutt Sharma (1978). Stone observatories in India, erected by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh of Jaipur. Bharata Manisha. p. 57.

6. Ajay Verghese (2016). The Colonial Origins of Ethnic Violence in India. Stanford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8047-9817-4.

7. Yamini Narayanan (2014). Religion, Heritage and the Sustainable City: Hinduism and urbanisation in Jaipur. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-135-01269-4.

8. Catherine B Asher (2008). "Excavating Communalism: Kachhwaha Rajadharma and Mughal Sovereignty". In Rajat Datta (ed.). Rethinking a Millennium: Perspectives on Indian History from the Eighth to the Eighteenth Century : Essays for Harbans Mukhia. Aakar Books. p. 232. ISBN 978-81-89833-36-7.

9. Virendra Nath Sharma (1995). Sawai Jai Singh and His Astronomy. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 2, 98. ISBN 978-81-208-1256-7.

10. Sarkar, Jadunath (1984, reprint 1994) A History of Jaipur, New Delhi: Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-0333-9, p.157

11. "Military History & Fiction: Shekhawati". web.archive.org. 20 October 2006. Retrieved 20 August2020.

12. Vir Vinod, Rajasthan Through the Ages By R.K. Gupta, S.R. Bakshi pg.156

13. Bowker, John, The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, New York, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 103

14. Umasankar Mitra (1995). "Astronomical Observatories of Maharaja Jai Singh" (PDF). School Science. NCERT. 23 (4): 45–48.

15. Sharma, Virendra Nath (1995), Sawai Jai Singh and His Astronomy, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., pp. 8–9, ISBN 81-208-1256-5

16. Baber, Zaheer (1996), The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India, State University of New York Press, pp. 82–90, ISBN 0-7914-2919-9

17. ‘Īśvara Vilāsa Mahākāvya’, Ed. Bhatt Mathuranath Shastri, Jagdish Sanskrit Pustakalaya, Jaipur, 2006

18. Sharma, Virendra Nath (1995), Sawai Jai Singh and His Astronomy, Motilal Banarasidass, ISBN 81-208-1256-5

Bibliography

1. Bhatnagar, V. S. (1974) Life and Times of Sawai Jai Singh, 1688-1743, Delhi: Impex India

2. Sarkar, Jadunath (1984, reprint 1994) A History of Jaipur, New Delhi: Orient Longman, ISBN 81-250-0333-9

3. Jyoti J. (2001) Royal Jaipur, Roli Books, ISBN 81-7436-166-9

4. Tillotson G, (2006) Jaipur Nama, Penguin books

5. Schwarz, Michiel (1980) Observatoria : De astronomische instrumenten van Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II in New Delhi, Jaipur, Ujjain en Benares, Amsterdam: Westland/Utrecht Hypothekbank

6. Sharma, Virendra Nath (1995, revised edition 2016) Sawai Jai Singh and his Astronomy, Delhi: Motilal Barnasidass Publishers

External links

• Genealogy of the rulers of Jaipur