The Tribune (Chandigarh)

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/10/20

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

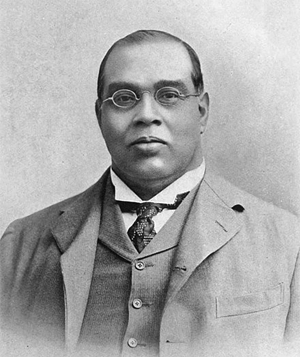

To eke out a living, both Freda and Bedi wrote school and college textbooks. Freda recalled that she wrote one about the art of precis writing. Bedi took on some more ambitious commissions, the most successful being his biography of the Sikh civil engineer, architect and philanthropist, Sir Ganga Ram. This remains the work for which he is best known in Punjab.17 There was another new publishing project, a new political paper, which engaged much of Bedi's energies and Freda's too -- and which added to their reputation in Lahore. Contemporary India had been highbrow; his new title Monday Morning was determinedly popular. As the name suggests, it was a weekly. They had spotted a gap in the market. The Lahore daily papers did not at that time work on Sundays and so did not publish a Monday edition. So a weekly hitting the newsstands first thing on Monday didn't have much in the way of direct competition.

No copies of Monday Morning have been located so it's difficult to judge its style and political agenda but for a while, at least, it sold well. 'Some English friends at the time called it laughingly a rag -- I suppose it was a bit of a rag,' Freda said, 'but it was a very outspoken, interesting weekly paper which came out on Monday morning and successfully deprived us of every bit of rest that we might have had on Saturday and Sunday as a result .... I learned a tremendous amount ... about how to bring out papers and press schedules and proof reading and a number of other things and we got a lot of fun out of it. And this helped the family finances somewhat because advertisements began to come in.'18

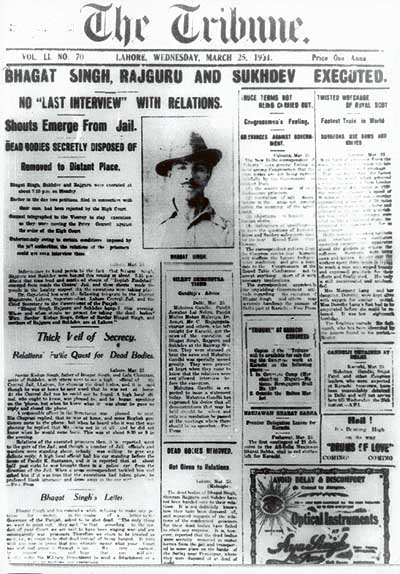

Monday Morning became a serious irritant to the authorities. 'This magazine had a very profound effect, because it was very militant,' Bedi recalled, 'totally anti-fascist in character, because anti-fascism was the wave of the times, and naturally it had to be anti-British, and it became one of the big exposure magazines. Any exposure which nobody would publish, we would publish.' Bedi claimed, with perhaps a measure of exaggeration, that the weekly achieved a circulation of 40,000 after six months, and so alarmed Lahore's main nationalist daily, the Tribune, that the paper tried to coerce newsagents into not selling their weekly rival. Bedi's main collaborator on the paper was Jag Parvesh Chandra, later a prominent Congress politician in Delhi. He recalled gathering with others at the Bedis' huts to work out how to start the paper, and the excitement of its early impact:

'the paper became a mouthpiece of the nationalist movement and was a success from the start.'19 Another of the Monday Morning team was the actor Balraj Sahni, then in his mid-twenties and something of a political innocent. Bedi insisted that he warned Sahni against getting involved in the messy world of political journalism. 'I said, "My Dear Balraj, look here. This is politics. If it were a literary magazine, I would say gladly come. Running a political weekly without any funds is a dog's job and we are dogs, we are out to be whipped by our own choice. You are an artist."'20 Balraj duly bailed out after three months. His younger brother, the novelist Bhisham Sahni, gave a somewhat jaundiced account of the hand-to-mouth launch of the paper:the editors had neither the resources nor the know-how of a weekly journal. Their enthusiasm and youthful energy were their only assets. It was planned that the paper would cover, besides news, cultural events and contain stories and poems, as also articles projecting socialist thought and ideology.

We waited eagerly for the first issue of the paper, but when at last it came, my heart sank. It was a two-sheet paper, full of printing mistakes .... The second issue, a week later, was even worse, so far as printing mistakes were concerned and we feared that such a paper was not destined to last long. ... Meanwhile we received a letter from a relative living in Lahore, saying that he had met Balraj inside a printing press, where he sat on the floor, unshaven, in high fever, correcting proofs and that Balraj looked tired and exhausted.21

The family was greatly relieved when they learned that Balraj had walked out on Monday Morning. 'The experience had left him sad, but a good deal wiser.'

As the international situation became more tense, and the prospect of war loomed, the left in Punjab organised against military recruitment. This deeply alarmed the Imperial authorities who were in any event finding the enlistment of new soldiers more difficult, in part because of the growth of nationalist sentiment. Recruits from Punjab constituted fully half of the soldiers in the British Indian army.22 They had proved their worth in France and Flanders in the First World War and were again to be conspicuous on battlefields far from India in the Second World War. In September 1938, Bedi's involvement in anti-recruitment activity prompted his most serious clash with the authorities -- as Freda explained in a letter to her old friend Olive Chandler:Bedi got arrested on a political charge ... Some hirelings of the Punjab Government broke up an Anti-Recruitment meeting at which Bedi was presiding (also breaking his head from behind, quite a nasty cut!). Later they had the audacity to arrest him, along with twenty-seven others, for rioting!! Just a ruse to prevent Anti-Recruitment propaganda, at a time when it was quite legal ... To cut a long story short, Bedi + the others were finally allowed bail + the case has been dribbling on (without coming to any conclusions) for the last nine months. It is what is known as a 'harassment case', trying to put everyone to the maximum amount of trouble. When it will end, + with what result we don't know -- they have only a very rocky concocted case again[st] them all, but the Government has got away with worse.23

The saga ended eighteen months later, when Bedi was convicted by a magistrate in Lahore of 'delivering an alleged anti-war speech in a public meeting outside the Railway Station' and was sentenced to two years rigorous imprisonment -- though by then he was already behind bars.24

By the time Freda wrote that letter to her old Oxford friend in the summer of 1939, Monday Morning had folded: 'after terrific hard work, sometimes from eight in the morning to eight in the evening, with scarcely a day's break, it has had to stop. Journalism in India is a tragic struggle against advertisers + newsagents who sit on bills + never pay up + it's practically impossible to carry on without strong financial backing which, as all over the world, a "left" newspaper can rarely get!'25 It had survived for about eighteen months.

***

Freda Bedi's wartime incarceration in Lahore Female Jail is the act of valour which forged her reputation as a nationalist icon. Thousands of Indian nationalists and leftists were detained for opposing India's participation in the Second Wodd War. Vanishingly few of these were English and white skinned and so identified in the public mind with the coloniser rather than the colonised. Freda was, of course, both undeniably English and unequivocally on India's side. She was jailed as a deliberate act of protest and renunciation -- offering herself up for arrest under an initiative launched and overseen by Mahatma Gandhi, who personally approved all those who were to be his satyagrahis, or disciples of truth. She was the first, and perhaps the only, European woman to be part of this phase of Gandhi's nonviolent protest against the Imperial power. For her, as for so many others, jail strengthened political resolve and extended the network of nationalist sympathisers. It also provided a window on the lives and tribulations of those so often beyond the view of middle-class India -- the women who shared the prison grounds with her not out of political commitment but because of the desperate acts they had been pushed to by a profoundly unequal and patriarchal society. That, as much as the informal political meetings and study classes, was a part of Freda's education in jail.

War was declared in September 1939. The tensions within the Congress Socialist Party between communists and others were by now acute. But all agreed, initially at least, on the need to oppose the war -- the Congress because Britain's Viceroy in New Delhi had declared that India was at war with Germany without the agreement (or indeed seeking the agreement) of India's political leaders, and the communists because Moscow, in the wake of the Nazi-Soviet pact, had declared that this was an imperialist war. By the end of October 1939 more than 150 Punjabi politicians were in jail, and by the end of the following year that number had swelled to many hundreds. Punjab led the rest of India in the number of communists and socialists detained -- generally on the grounds of their anti-war and anti-recruitment activities.1

B.P.L. Bedi was, by his own account, publishing anti-war literature and using his contacts in the rail unions to help get the leaflets circulated around the country. He was not among the early wave of arrests, but he knew that he was likely to be detained before long. That knock on the door came in early December 1940. 'I had just come from Lahore and the British Superintendent of police had arrived,' Bedi recalled. 'Soon after my servant told me that there seemed to be some peculiar movement of people round the bushes so I immediately sensed that the moment of my arrest had come. Within ten minutes of his announcing this, he arrived and in a very British way said, "I am afraid I have to arrest you.'''2 In an even more British manner, Bedi asked the police officer to sit down and have a cup of tea while he packed a blanket, some clothes and a few books. Bedi was at this time on the national executive of the Congress Socialist Party and his arrest under the Defence of India Act was front page news in the Tribune. It reported that as he was being driven away in the police car, 'Mrs Bedi raised loud shouts of "Inquilab Zindabad"' -- a communist slogan which best translates as 'Long Live the Revolution'.3

Bedi was held briefly in the jail in the town of Montgomery (now Sahiwal), still in Punjab but some distance from Lahore, and then was sent more than 400 miles away to Deoli, a remote spot on the edge of the Thar desert in what is now Rajasthan. A Victorianera military base there had been turned into a detention camp -- a concentration camp, the communists complained -- for political detainees from across India. It had a long history of being used to lock-up 'undesirables', and continued to fulfil that role in later years. From 1942, the camp housed prisoners of war -- and in 1962, it was used to intern Indians of Chinese origin during a brief India -China border conflict. As soon as he reached Deoli, Bedi began to protest against his detention -- refusing to carry his bags into the camp as a statement, in his own words, that the 'revolutionaries' had arrived. 'At Deoli were nearly four-hundred persons, who were all Leftists ... From the moment we arrived we started planning to create more trouble and a hunger strike was on the agenda.'4

Freda can hardly have been surprised by her husband's arrest, but she was certainly angered by it. 'On December 4th, 1940, the lights in the huts went out,' she recalled:Bedi was taken away for indefinite detention for being a Socialist, for hating Fascism, for hating the Imperialist exploitation of India. There was no oil in the lamps when the police came, and we groped around in the dark getting a few clothes together. Pug drooped his tail dejectedly when he said goodbye.5

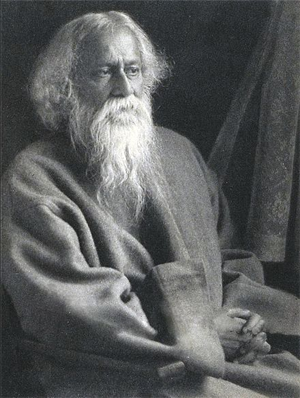

A couple of days later, she announced that she too intended to flout the wartime emergency regulations and was happy to take the consequences. The Tribune reported that she had sought Gandhi's permission to give herself up for arrest. 'Should Mahatma Gandhi's permission be secured, Mrs Bedi will be the first English lady to offer satyagraha in the civil disobedience campaign.'6 Freda regarded Gandhi's campaign as 'halting and incomplete' -- but it was at least action on a nationwide scale. 'There should have been a great, a magnificent up-surge of the nation. Gandhiji decreed otherwise, and chose his men with the greatest care. Only the few were to go to jail to protest for the many. It was to be a demonstration to the world of India's national right.'7

At the end of January, Freda heard that Gandhi had agreed to her request -- she believed she was the fifty-seventh volunteer to be chosen as a satyagrahi in this stage of the civil disobedience campaign. This was Freda's boldest political act -- she was putting herself forward for arrest and imprisonment to protest against her native country's treatment of her adopted country. 'She said that she was born in England but had adopted India as her mother country,' the Tribune reported, 'and would wish to be known as an Indian woman.'8 It was also an impetuous move. She had a six-year-old son whose father had just been detained indefinitely, and rather than be around to offer support and reassurance, she decided that the political imperative was what mattered most. She admitted being torn about what to do. 'It was a terrible blow to lose B.P.L. and his cheery daily support in life's problems. And his mother, my son, the adopted boy Binder and myself were left alone in the huts. I didn't want to make things worse on the domestic side but on the other hand I felt that I should back up the nationalist movement in whatever humble way I could, even if it meant suffering some months in prison. I felt I could trust my mother-in-law to look after the boy and my brother-in- law to see that the family did not lack support at that time.'9 So the family arranged to move from the huts to Bedi's home village where they would be able to live comfortably with many members of the extended family there to help. In the carefully choreographed way of these protests, Freda wrote to the district magistrate in the town of Gurdaspur to tell him exactly when and where she intended to stage her act of civil disobedience. 'Mrs Freda Bedi left for Dera Baba Nanak,' the Tribune announced on its front page, 'where she will offer satyagraha on 21st [February] at 11 a.m.'10

'So I packed up my little household, put that furniture with this friend, that with another, here my crockery and there my few loved possessions,' Freda wrote. 'I left Lahore station, in a welter of photographs and flower garlands. The women in the women's compartment were inquisitive ... "It is degrading that Indians should be treated like this," I said. "Somebody had to do something: we can't just all sit down and keep quiet about it." "But what does your husband say about it?" one matron asked. "He is in jail himself," I replied. "Ah ... " her eyes were turned in pity towards me, "now I understand." It was the wife following her husband. That was as it should be.'11 Freda was following in her husband's footsteps not out of blind loyalty; rather in a marriage which was based on intellectual and political camaraderie, she saw it as the natural course of action. Bedi of course did not offer himself for arrest; he was detained as an anti -war activist. It's not at all clear whether they had discussed what the family should do in his absence, but Freda never suggested that he had endorsed her intention to become a satyagrahi.

In writing about the eve of her arrest, Freda lapsed into a reflective mode which points to the complexity of her political commitment and the awareness that she was about to make an act that would come to define her. In the Bedi household in Dera Baba Nanak, she slept alongside Bhabooji, Ranga and Binder in a room lit by a spluttering oil lamp -- but she felt lonely and vulnerable:Little bodies and one big round body were lumped under the fluffy cotton-stuffed quilts. There was somebody still banging pots and pans in the kitchen. I could hear Pug and Snug barking somewhere in the garden. Suddenly, I felt alone, agonisingly alone. I could have wept for my sheer aloneness. I wanted to talk to Bedi, to have his cheery voice near me. What I wanted to say I could not say in my limited Punjabi. I doubt if I could have said it in English, or even mentally told myself what I felt. I suppose in all crises of our life we get that feeling of isolation as though we are treading a path into the future and are treading it, for all the love that surrounds us, quite alone. When we first leave home, when we marry. When we have a choice to make at some cross-roads of our life and endeavour .... And on the borders of that aloneness, of that feeling of smallness in the face of the immensity of the unknown, there comes another feeling, which is interwoven with it and part of it and yet not part of it, of being given the strength to carry on, of not being alone any more. Of being a part of something greater than the mere individual human body.12

This was written within a couple of years of Freda's imprisonment and a decade before she became interested in Buddhism, but there is a pronounced spiritual aspect to her account. Freda became comfortable with the feeling of isolation she describes -- it was another border she chose to cross -- and instinct, or faith, guided her at what she calls the crossroads of her life, which gave her a sense of comfort that she was on the right track.

We wrote a letter to the district magistrate,' Freda recalled, 'saying that we would break the law by asking the people not to support the military effort until India became democratic and that India must get her elected government first. But since we sent the letter, we effectively prevented ourselves from speaking because on the day we were supposed to speak we were naturally arrested before this happened.' Exactly what happened in the village that February morning is difficult to establish beyond doubt through the layers of valorous nationalist narrative and family folklore.13 Freda's own account is both the most straightforward and most credible. Her intention was to shout anti-war slogans in Punjabi in the village streets. She heard that the local inspector had summoned an English officer from Amritsar, thinking it best to have an Englishman to hand when an Englishwoman was placed under arrest. 'At eight-thirty they arrived. In the centre was the local Inspector with a beard. He came forward politely, "regretting that it is my duty but I must arrest you." The turbanned police-officer on his left had a half-smile. To the right was the European Inspector from Amritsar in an unwieldy topee [hat]. He was surprisingly small and had a walrus moustache. He looked like Old Bill: I wanted to laugh, and the corners of my mouth twitched. "Yes, I am quite ready. Take me along with you.'"The little procession started towards the Police Station winding its way back through narrow brick-paved gulleys of the village. The shopkeepers came to the door of their shops, with their hands folded in greeting. The women crowded on the flat roofs to see us go, and sighed in the doorways. A few young men and boys began to attach themselves to the little group and shouted wildly 'Freedom for India. Long live Gandhiji. Long live Jawaharlal Nehru. Long live Comrade Bedi. Release the detenues.' We reached the elegant grey Amritsar car parked under the peepul tree near the only pucca road. Garlands were thrown over the radiator of the car, through the windows. They were removed immediately: 'garlands not allowed'.14

At the village police station, Freda was questioned by the police officer she had nicknamed Old Bill, who she later discovered had 'Irish blood and a kind heart' -- though the interrogation was limited to questions along the lines of 'What colour would you call your hair?' Under the wartime regulations, trials under the Defence of India Act could be held straightaway and without any legal formality or indeed representation. Freda was taken from the police station to the dak bungalow, the guest house where visiting officials stayed, and that's where her trial took place that same morning:It was finished in fifteen minutes. The man on the other side of the table was quite young still, and looked as though he had been to Oxford. His face was red.

'I find this as unpleasant as you do,' he murmured.

'Don't worry. I don't find it unpleasant at all.'

'Do you want the privileges granted to an Englishwoman?'

'Treat me as an Indian woman and I shall be quite content.'

... The room was deserted but there was a noise, and two Congressmen walked in. They had been allowed at the last minute to attend the 'public trial'. They carried a round shining brass tray filled with flowers and sweetmeats.

Wait until you have heard my judgment, perhaps you will not want to give them then.'

Six months Rigorous Imprisonment.

'She cannot have the garlands. Give her one or two of the sweets.'15

Freda had expected the jail sentence, but not the specification of rigorous imprisonment. 'Hard labour was the point,' she said many years later, 'and none of the Indians arrested got hard labour in the Punjab except myself None of the women at least. Whether it was the ignorance of the young civil servant, Englishman, who gave the sentence, very regretfully and with many apologies .... Or whether it was that they wanted to make an example of me because I was the first, maybe, western woman to offer satyagraha at that time.' Once the sentence was pronounced, Freda was put back in the car which was mobbed by well-wishers, many of them members of the Bedi clan, as it set off to Lahore jail.

News of Freda Bedi's arrest and sentence once again made the front page of the Tribune, complete with a posed portrait photograph. The following day's paper offered a fuller account of her arrest and sentence- - which emphasised the level of local interest in and support for her action, reporting that she was 'profusely garlanded by the public' after sentence was passed in a trial in which she had refused to participate. The Reuters news agency eventually picked up the story -- and a few weeks after the event, the jailing of 'the first Englishwoman to join Mr Gandhi's passive resistance movement' made front page news back in Freda's home city [Derby Telegraph] with the headline: 'Derby Wife of Indian Sentenced'.16 Freda of course regarded herself as Indian but her act of protest gained attention and achieved impact precisely because she was not Indian. It's a paradox which didn't greatly perturb her. She seems to have managed to negotiate these conflicts of identity without a lot of soul-searching. However much she might seek to forsake the special status accorded in colonial India to those with white skins, it was an indelible aspect of her life there. Inspector Price, the moustachioed Irishman, had been sent from Amritsar to Dera Baba Nanak to be present at Freda's arrest because it felt inappropriate for a white woman to be detained simply by Indian policemen. It was another example of the awkwardness of the British authorities in India in the face of a British woman who had sided with India. They had dealt with British men who had allied with and supported Indian leftist and nationalist movements -- indeed there were three British communists among the defendants in the long-running Meerut conspiracy case which was widely discussed in both India and Britain in the early 1930s and for which Oxford's October Club had collected money -- but a white woman directly challenging Imperial rule was a much rarer phenomenon.

Freda wrote luminously about her time behind the mud walls of Lahore's female jail (after her release, she and a fellow prisoner persuaded the authorities to rename it, with greater verbal precision, as Lahore women's jail). Within days of her release, she began a short series 'From a Jail Diary' in the Tribune, concerned particularly with the 'criminal' prisoners -- she was a 'political' -- she met there. This developed into a much more ambitious account of her time behind bars -- a day-by-day jail diary which is the spine of her book Behind the Mud Walls, and is the most resonant and affecting of her writings. She weaves into her account of imprisonment the personal, the political, the observational, with reflections of the temper of Indian nationalism and more so about the inequity, the gender injustice, which consigned so many of the non-political inmates to long terms of confinement. It is one of the most remarkable and readable accounts of Indian nationalist endeavour at this time. The jail diary is a well-established literary form and as the struggle against colonialism led to the detention of intellectuals who would otherwise be unlikely to land in jail, there are many nationalist narratives of imprisonment. Few are quite as compelling, as simple and unadorned, as the account Freda Bedi published as 'Convict No. 3613'.17

'The mud road to the "Female Jail" was long and dusty,' Freda wrote. 'The gates looked like the Lion House at the Zoo.'The gates opened. We went in. They shut. It was cool like a cellar in the entrance room. Beyond was a second door: a sheet of solid iron like a safe. To the right the Deputy Superintendent's room. I was motioned towards the door. It was bare and depressing. A cold stare came from the aging woman in a drab frock on the other side of the table.

'What is her crime?'

'Political ... Six Months Rigorous Imprisonment,' said 'Old Bill'. After a few minutes, he turned and left.

The world beyond the barred gate seemed a long way away.

'Give over all your jewellery and money,' said the Deputy Superintendent.

'I haven't got any jewellery.'

She pointed to my left hand.

'That is my wedding ring.'

'It is also counted as jewellery,' she replied.

I looked at my wedding ring. It had never left my hand since that day in Oxford when Bedi put it on. Reluctantly, I used my last weapon.

'I am an A Class prisoner. Are you within your rights in taking it away?'

... There was a shuffling sound, a sort of subdued commotion, on the other side of the inner iron door. I could see an eye glittering through the peep-hole. Shouts of 'Gandhiji ki Jai' [Long live Gandhi] and lots of 'Zindabads'. It seems the 'politicals' had found out that I had arrived.18

The small group of political prisoners in the women's jail banded together: on Freda's first evening 'behind the mud walls', they spun together, 'our common badge and discipline as satyagrahis'. On one occasion they staged a twenty-hour spinning relay -- Freda declared herself 'not very thrilled at the idea, but doing something has got its moral exhilarations ... I took my turn at 4.30 a.m.' There was also collective reading of Hindu scriptures and talks, meetings and education sessions. The camaraderie among these women activists was intense and nourishing. They were responsible for their own cooking, and the jail regime was sufficiently relaxed to allow them to meet fairly freely, staging informal political gatherings and on one occasion having a picnic and dance in the prison grounds.

Freda practised yoga in the mornings. 'I am doing them with no "spiritual" intent, only to keep healthy in the roasting months ahead of me. Find they are simple, rhythmical, and invigorating.' She read alone from Hindu religious writings and from novels by Aldous Huxley and John Steinbeck -- 'feel the lack of political books,' she noted, 'we forget how dependent we are on them.' She described herself on entering the jail as a professor of English and college connections sometimes resurfaced in surprising ways. 'The new Deputy Superintendent came to-day,' Freda wrote in her diary. 'It seems she was one of my old B.A. pupils. She is touched that 1 am here. 1 feel amused.'

Alongside the fairly unexacting routine, for the political prisoners at least, was the hardship of the raging summer heat which turned the very basic sanitary facilities into a 'horrible' ordeal. 'I was trying to decide the other day what annoyed me most, physically, here, and I decided it was the dilemma of sitting in the latrine with (1) either my face in a dirty sacking curtain; or (2) throwing up the curtain and being frightened of somebody arriving quietly and catching me. The latrines are uncovered to sun and rain and we are exposed to the elements .... One can get used to anything, and one has to shut one's eyes and ears and brain to it, but if I give way to what I really felt, I could be sick every time I go near the place.'19

Freda made two strong political friendships -- with the peasant leader Bibi Raghbir Kaur, described by Freda as 'my political mother-in-law', and with the renowned Arona Asaf Ali, who was about Freda's age and had form as a political prisoner (after her release from Lahore jail she famously went underground as a pro-independence activist). Aruna was from Delhi, and housed in a different block, but they arranged to meet regularly. 'Aruna came for tea,' Freda wrote in her account of jail life a month into her imprisonment. 'She is a comfort, and I am happy with her. With her I can exchange thoughts -- she's the only one who can give me that satisfaction. Although I manage in Hindustani, I know so few words that it is a continual frustration to try and express myself. Besides which, quite apart from speaking to her, or any question of language, I am fond of her.' As a team they worked well, all were leftists as well as admirers of Gandhi, and they managed to hold a May Day meeting inside the prison:A few words from me on its significance. Attari Devi sang 'Inquilab Zindabad'; Raghbir Kaur spoke in Punjabi on the peasant and the worker; Aruna a little on Lenin and the significance of the Russian revolution. A funny rambling affair, but we did manage to celebrate it. Had a gnawing feeling inside me because of newspaper reports on Deoli, couldn't eat properly, felt like vomiting. The temperature has gone to 116. Mentally, it doesn't worry me.20

Concern about the plight of her husband was a constant preoccupation -- she was anxious about reports of a hunger strike at the much more spartan and remote Deoli camp and worried when she didn't hear from him for weeks on end. 'In his confinement, he must be thinking of me, and indeed I have felt him almost physically with me these last stirring days,' she wrote on the second day of her detention. The occasional telegram from Bedi gave her a big boost. One came on Ranga's seventh birthday -- 'Congrats for Bunny Heart'. 'Such a silly telegram and so nice to get it.' Freda missed her son too and was delighted when permission was given for him to spend a few days with her, sharing her bed. Ranga too -- who still has notes he sent as a child to his parents in their separate jails, one in Punjabi and the other in English -- was thrilled to spend time with his mother. But he wasn't allowed to accompany her during the day as she worked, and some children of the non-political detainees jeered and mocked him, so it was a short stay.

[Cont'd below]