by Wikipedia France

Accessed: 9/11/20

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Jean Calmette

Birth: April 5, 1692, Rodez France

Death: February 1740 (at 47), Chikballadur India

Nationality: French

Country of residence: India

Profession: Jesuit priest

Primary activity: Missionary, Indianist, writer

Training: Sanskrit, philosophy and theology

Complements: Calmette is the first westerner to have access to the sacred texts of the Hindu Vedas.

Jean Calmette, born on April 5, 1692[1] in Rodez, Aveyron (France) and died in February 1740 at Chikballadur, Karnataka(India), was a priest Jesuit French, missionary in South India and Indianist.

Summary

First years in India

Entered at 17, October 4, 1709, at the Jesuit novitiate in Toulouse, Jean Calmette taught for a time in France and received priestly ordination before leaving for India in 1725. He arrived in Pondicherry on August 21, 1726. For a few years he was a missionary in the Tamil-speaking region around Vellore.

Initiation to Brahminism

From 1730 to his death he will be in the Telugu speaking region, (now Andhra Pradesh). In Ballapuram, Calmette attended Brahminic schools where Sanskrit and other Hindu disciplines (including astronomy and natural sciences) are taught. There he reached such a level of knowledge of the language that the Brahmins agreed to initiate him into the science of the sacred texts, the Vedas. This favor can be considered as a true religious initiation into Hinduism. Max Müller wrote that Father Calmette is the first to obtain the full text of the four Vedas. In these Vedas, according to Calmette himself, there are treasures of literature, treatises on grammar, philosophy and astronomy.

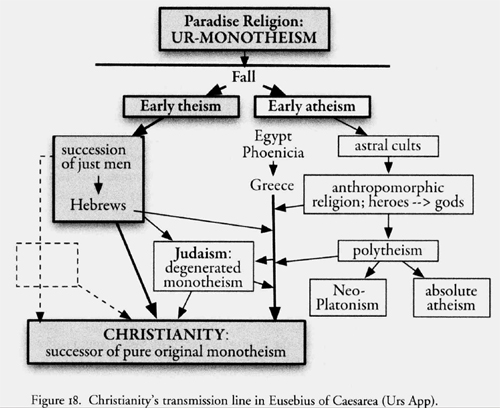

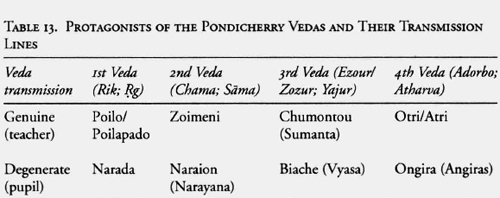

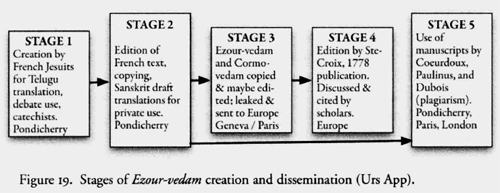

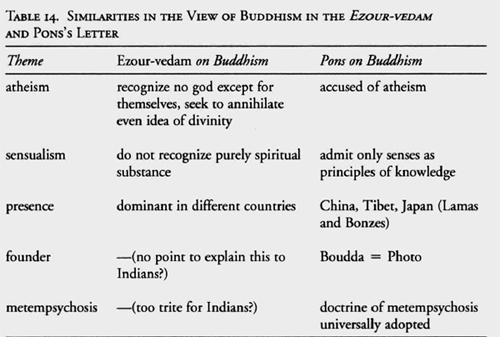

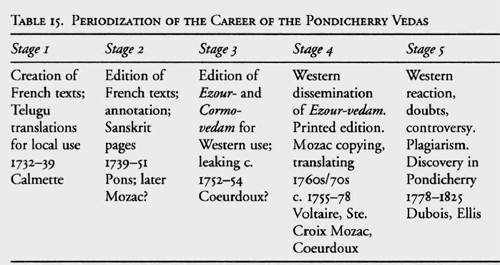

Ludo Rocher's detailed study on the “false Veda” Ezur vedam mentions Jean Calmette among the potential authors of this famous text [2]. New evidence presented by Urs App in 2010 indicates that the author of the Ezour vedam was in fact Jean Calmette; this text, published in 1778 by Guillaume de Sainte-Croix, was an important source of nascent Orientalism as well as the beginning of European studies on the Vedas and the religious and philosophical literature of ancient India [3]. He played an important role in the thought of Voltaire from 1760.

[cont'd from Roberto de Nobili, by Wikipedia]

Jean Calmette

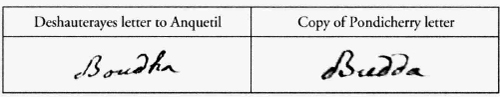

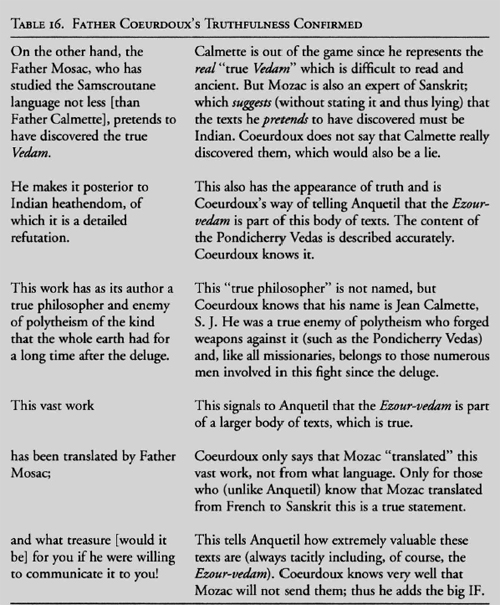

In the meantime a second Jesuit was credited with the authorship of the EzV: Father Jean Calmette (1693-1740). The source of this attribution seems to be a number of statements by Calmette himself, which might easily be interpreted as coming from a person most likely to have composed the EzV. In 1733 he writes 46 about his involvement in collecting Oriental books for the library in Paris, and adds: "We already derive much benefit from it for the advancement of religion. For, having thus acquired the most essential books which are like the arsenal of paganism, we forge weapons out of them to combat the doctors of idolatry, and it is these weapons that hurt them most deeply. They are: their philosophy, their theology, and above all the four Vedams which contain the law of the brames, and which India has from time immemorial regarded as the sacred book, the book with unquestionable authority, and derived from God himself." Two years later he writes47 to Father Delmas: "Since the time that the Vedam, which contains their sacred books, came into our hands, we have extracted from it those texts which are most apt to convince them of the fundamental truths that destroy idolatry. For the uniqueness of God, the characteristics of the true God, benediction and reprobation, they are all in the Vedam. But the truths which are contained in that book are spread across it like gold dust across heaps of dirt; for the rest, one finds in it the basis of all Indian sects and, probably, the details of all the errors that make up the body of their doctrines. The method we adopt with the brames is as follows. We first make them agree on certain principles which simple reason has introduced in their philosophy; and through the consequences we draw from these we show them without difficulty the erroneous character of the opinions which are current among them. Especially in a public discussion they cannot close their eyes to arguments drawn from the sciences themselves, and even less to the demonstration that follows, in which one shows them by means of the very texts of the Vedam that the errors which they earlier rejected are part of their law. Another method of controversy is to establish the true and unique nature of God by means of definitions and propositions drawn from the Vedam. Since this book has among them the highest authority, they cannot help admitting them. After that the plurality of gods is easily refuted. If they reply that this plurality is in the Vedam -- which is correct -- one points to the fact that their law is contradictory and that it is inconsistent with itself." In a third letter Calmette refers48 to his ability to write verses in Sanskrit: "I have not missed the opportunity to compose a few verses in this language for the sake of controversy, to oppose them to those composed by the Indians." And Father Coeurdoux, writing in 1771, thirty one years after Calmette's death, reports (Anquetil 1808a:687) that there are, in the possession of the Jesuits at Pondicherry, "a few samskroutam verses by Father Calmette."

The principal champion of Calmette's authorship was Julien Bach, S.J. He notes (1848:60) that Calmette studied Sanskrit and sent the Veda to Europe. "But this was not all; being above all desirous, as a missionary, to convert the idolaters to whom he had been sent; knowing from experience how impossible it is to eradicate Indian prejudices without going back to their source; noticing on the other hand that the origin of most brahman superstitions was the way in which the Vedas abused primitive tradition -- he applied himself first of all to extract a number of texts from these Vedas to combat the Brahmans with their own weapons." Twenty years later Bach (1868:12) repeats that Calmette composed the EzV, and he adds: "The form adopted by Father Calmette is the dialogue, similar to the form of the brahmanic Vedas. In it a missionary and a brahman speak alternately, both under ancient names, the brahman to expose his ideas according to the Vedas and Pouranas, and the missionary to refute them. Thus, if we accept with the missionary that Indian superstitions derive from primitive traditions altered by ignorance or their taste for fables, and if we give the term Veda its real meaning revelation, we have the entire work of the missionary in a nutshell: there was a Veda, a primitive revelation, and its tradition spread as far as India; but you, brahmans, have corrupted the Veda by mistakes of all kinds. I shall destroy these mistakes." Bach (1868:23) also relates an interview with the abbe Jean Antoine Dubois on the authorship of the EzV; Dubois introduced a minor variant: "It is by Father Calmette, he also told me. But, he added, many Missionaries have contributed to it."

Bach's hypothesis has not met with much success. Yet, Sommervogel, whose main purpose was to deny de Nobili's authorship (see p. 41), adds (1891:566) without comment "Father Bach has shown that the original is by Father Calmette." Hull advances two arguments in favor of Calmette. First, he quotes (1904:1232) "a correspondent from Trichinopoly," saying, not without a few inaccuracies: "The Ezur-Vedam was written by Father Calmette. This Jesuit was a very clever linguist; and he wrote the Ezur-Veda in Sanskrit as a kind of pastime -- not with a view of imposing it on the public. It it he taught the principles of natural religion as paving the way to Christianity. It was never used as a means of converting Brahmins; in fact the MS. remained unpublished till after the suppression of the Jesuits in France, when some one, having found it in Pondicherry, sent it to a society of savants in Paris. The work was deciphered and admired as showing the purity of the Hindu religion; but when the mistake was discovered they began to accuse the Jesuits of dishonesty for writing it so skillfully." Hull's second argument (1232-3) is that Sommervogel lists it as one of Calmette's works in his Bibliotheque. Heras, who finds (1927:389n) that "there cannot be more historical errors in a few lines" than in d'Orsey's statements on the EzV, and who is of the opinion that Japp's "unfounded accusation" of de Nobill has been "thoroughly refuted" by Hull, undoubtedly also follows the latter when he says that "there cannot be any doubt about the authorship of the Ezur-Veda, A French Jesuit, named Calmette, wrote it one century later," Calmette's name has also found its way into Streit's Bibliotheca Missionum (1931:82-3): "Among his linguistic works became famous: his Ezour-Vedam," followed by the erroneous statement that "Voltaire found a copy of it in the National Library in Paris."

For a reason which is difficult to ascertain the British Library catalogue has the following note under Sainte-Croix' edition: "A fictitious work, written in French by J. Calmette." The Library of Congress call numbers, of Sainte-Croix' edition and of both editions of Ith's German translation, also seem to indicate that the cataloguer attributed the EzV to Calmette. The most extravagant statement on Calmette, which reminds us of Japp's information on Nobili, is Dahlmann's (1891:19): Calmette acquired an extraordinary skill in handling the Sanskrit language, "and his famous poem, the Ezour Veda, which was so much talked about in his time, became instrumental in numerous conversions in brahmanic circles."

The earliest author who explicitly expressed doubts about Bach's hypothesis is Vinson. He (1902:293) cannot accept Calmette for the same reasons for which he rejects de Nobili (see p. 40): the Vedas from Pondicherry, besides exhibiting Bengali transliteration, are too voluminous to have been the work of one man. Besides, Maudave's "revelation" came only in 1760, twenty years after Calmette's death. Castets (1935:40) advances similar arguments: nothing in Calmette's correspondence reminds us in any way of the EzV which, moreover, cannot have been written by a missionary who never worked anywhere else than in the Telugu country. Della Casa (1955:54-5) does credit Calmette with the discovery of the Vedas copies of which, in Telugu script, were sent to Paris; but "everyone now agrees that Calmette should not be charged with the ungainly medley of brahmanic wisdom and Christian doctrine, called Ezour Vedam."

[cont'd with Antoine Mosac]

_______________

Notes:

46. Letter dated Vencatiguiry, 24 January 1733, to Mr. de Cartigny, Intendant general des armees navales en France. See Lettres Edifiantes et Curieuses (ed. Aime Martin, Paris: Auguste Desrez) 2, 1840, 611. For references to other editions, see Streit (1931:86, No. 321).

47. Letter dated Ballapouram, 17 September 1735. See ibid., pp. 621-2. References in Streit (1931:89, No. 337).

48. Dated 25 December 1737. Quoted by Vinson (1902:278), without indicating his source. Not listed by Streit (1931). Referred to by Hosten (1923:149) as from Darmavaram.

-- Ezourvedam, edited by Ludo Rocher

Writer in Sanskrit language

Calmette is passionate about Sanskrit and Orientalism. With the help of Brahmin friends he draws from the Vedas fundamental religious truths common to all religions such as the oneness of God, divine attributes, etc. He composes 'slokas' (texts versified in Sanskrit) containing the truths of the Christian faith (his work Satyaveda sara Sangraham contains 172) and translates the works of Roberto de Nobili into Sanskrit: The great catechism of the faith and the Refutation of the transmigration of souls. He also encourages his Christians to write in the sacred language. The Royal Library of Paris was enriched with many Telugu and Sanskrit manuscripts that he sent. Unfortunately the collection that he and his companions (Jean-François Pons, Nicolas Possevin, Gaston-Laurent Cœurdoux) had gathered in Pondicherry was lost during the suppression of the Company of Jesus (1773). Some claim that he was the real author of Ezour Veidam, a fake inspired by epic Sanskrit poetry collections, in an attempt to ridicule popular Hindu beliefs at the French court. On the other hand, the work could well be produced by other Jesuit missionaries.

This promising work was interrupted by the premature death of Jean Calmette in 1740; he was barely 48 years old.

Works

• (in Sanskrit) Satyaveda sara Sangraham

Bibliography

• J. Bach, Father Calmette and the Indianist missionaries, Paris, 1868

• Joseph Dahlmann, "Missionary pioneers and Indian languages." Trichinopoly: Catholic Truth Society of India, 1940 (cf. Rays Supplement, November 1941).

• G. Dharampal, La religion des Malabars:: Tessier de Quéralay and the contribution of European missionaries to the birth of Indianism, Immensee: Nouvelle Revue de science missionionnaire, 1982.

• Inès G. Zupanov, Marie Fourcade, François Pouillon (ed.), Dictionary of French-speaking orientalists, Paris, IISMM / Karthala,2008, 1007 p. ( ISBN 978-2-84586-802-1 , read online ) IISMM-Karthala editions, 2008 (see the biographical sheet)

External links

• Authority records :

• Virtual international authority file

• International Standard Name Identifier

• National Library of France ( data )

• University documentation system

• Gemeinsame Normdatei

• University Library of Poland

References

1. If this date is traditionally given, it will be noted that no baptism in the name of Jean Calmette can be noted in the parish registers of Rodez (Notre-Dame or Saint-Amans). On the other hand, a Jean Calmette was baptized on May 4, 1693. Only one family seemed to have this surname at that time, in this city, one can imagine that it is the same person. If this is the case, Jean Calmette was the son of François Calmette, doctor of medicine, author of a Summary of therapeutic medicine published in 1690 in Lyon, and of Marie-Jeanne de Jouery. ( Genealogies of Aveyron, by Bernard Aldebert)

2. Ludo Rocher (1984). Ezourvedam: a French Veda of the eighteenth century [1]. University of Pennsylvania Studies on South Asia 1. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, 1984. (ISBN 978-0-915027-06-4)

3. (in) Urs App (2010). The Birth of Orientalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 372-407. ( ISBN 978-0-8122-4261-4)

******************************

The Father Calmette and the Indianist Missionaries

by Father Julien Bach

of the Society of Jesus [Compagnie de Jesus]

1868

[Rough from French Edition of Le Père Calmette Et Les Missionnaires Indianistes (Litterature) (French Edition) on Google Books]

If there is an interesting point of view in the history of the Society of Jesus, it is undoubtedly that of the Indian missions. Saint Francis Xavier, their wonderful founder, has had successors worthy of him, who continued his work, whose conquests on the paganism are recorded in a justly famous collection. One of our most distinguished Indianists, professor of Sanskrit at the College of France, M. Eugène Burnouf, once gave them a testimony which I am happy to be able to invoke at the beginning of this article. As I was talking to him about the missions in India, he suddenly got up with animation and showed me in his library the collection of Edifying & Curious Letters [Jesuit Accounts of the Americas, 1565-1896], saying: "There are men! They understood their mission."

This opinion of the Orientalist scholar is consistent with the impressions these letters left in the scholarly world. The conversion of idolaters, the establishment of the Catholic Church in the midst of an enemy civilization, such was the work with which the missionaries were charged, a difficult and thankless work that was necessary to undertake and accomplish by men of devotion and the sacrifice of heroes, such as the Catholic Church has given birth to thousands in all ages, and we can say that missionaries of India have not been below their task.

The deep roots that Christianity has grown in these climates, are known to us by the collection I mentioned just now, and if you judge they have produced fruit, and yet produce every day, read the letters of the new mission of Madurai recently published by the P. Jos. Bertrand, who, after having been superior of this mission, had the happy idea of revealing to Europe some of the works of which he was the witness or the actor. This work, added to the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith, showed once again how powerful the charity of missionaries had been for the transformation of India.

But these big-hearted men did not stop at working for the establishment of the Christian religion in India. They have again made, and, so to speak, playing with each other, numerous conquests for the advancement of human knowledge. It is through them that literary history, philology, and ethnography emerged from the swaddling clothes where routine held them tight. There were those who knew how to wrest from the Brahmins the secret of their language and their philosophy, and who dared to engage in a hand-to-hand struggle against them, as admirable from the literary point of view as from the religious point of view. Such was the P. Jean Calmette, prime Indianist, as will the view. A study of his work is not without importance: it is connected with the history of Brahminism and Eastern philology, and in this respect it deserves the attention of scholars. so rich a mine of Sanskrit literature, and if it finds there unexpected treasures, is it not interesting to research who was the Christopher Columbus of this new world? The account of his first investigations is certainly worthy of exciting our curiosity.

The Carnate was a French mission formed around 1703 on the model of the Portuguese mission of Maduré; the Jesuits had adopted there, since the initiative of Father de Nobili, the way of life of the Brahmins, in order to be in more intimate relation with the populations, without having to fear national antipathies. In Pondicherry was the central establishment. Advancing towards the north and inland, the missionaries had found a population that differed from that of Madurai as much as Indians can differ between them. The same idolatry, the same uses based on the distinction of castes, the same horror for the Pranguis: ...

The opponents in this combat were mainly Brahmins who considered the Europeans worse than outcasts. Calmette explained: "Nothing is here more contrary to [our Christian] religion than the caste of brahmins. It is they who seduce India and make all these peoples hate the name of Christian" (p. 362). The label Prangui, which the Indians first gave to the Portuguese and with which "those who are ignorant about the different nations composing our colony designate all Europeans" (p. 347), was a major problem from the beginning of the mission, and the Jesuits' Sannyasi attire and "Brahmin from the North" identity were in part designed to avoid such ostracism. The fight against the Brahmin "ministers of the devil" who "never cease to pursue their plan to ruin both our church and the Christians who depend on it" (p. 363) is featured prominently in Calmette's letters, and it is clear that the Frenchman meant business when he spoke about stocking up an arsenal of weapons especially from the four Vedas for combating these doctors of idolatry.

-- Anquetil-Duperron's Search for the True Vedas, Excerpt from The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

...but, instead of the Tamil language, it was the Telugu; instead of the government of the Naïques du Maduré, it was, since the capture of Visapour, the Mohammedan domination of the Grand Mogul; and we know that the Nawabs of India showed, in imitation of the court of Delhi, a great sympathy for the Christian missionaries.

It also appears that the Brahmins of this region were less fanatic and more educated than those of the Tamil country. In Ballapouram, in particular, there was a kind of academy, whose doctors willingly entered into contact with the Roman Brahmins. This is the theater where several Indian missionaries will be shown, and especially the one which is the subject of this article. Party Penmarck the beginning of 1726 the P. Calmette happened in the month of October in Pondicherry, and after several years of trials in various homes of the mission, he was sent to Ballapouram. Gifted with a great facility for languages, and a penetration of mind equal to his zeal, he soon saw all the advantage that a missionary could derive from knowledge of the Brahminic books, and he applied himself tirelessly to the study of Sanskrit, or Sanscrutan, as we said in the Carnate.

Several converted Brahmins were of great help to him for this. He conversed with them frequently, and he was thus able to make rapid progress, not only in their language, but also, a precious thing, in the true genius of Brahminism. As they took pleasure in transcribing various passages from the Vedas for him, he learned from memory some tirades; then, when he met Brahmins who were still pagan, he sold them out, and used them to object to them. Here is what he wrote in 1730: “Until now we had had little trade with this order of scholars; but since they realize that we hear their science books and their Sanscrutan language, they start to approach us, and as they have enlightenment and principles, they follow us better than the others in the dispute, and more readily agree with the truth."

The breach was made, but for the P. Calmette it was not enough. This missionary, desiring above all else the conversion of idolaters, knowing from experience how impossible it was to dispel the prejudices of the Indians without going back to the source of their beliefs, seeing on the other hand that the origin of most Brahminic superstitions was the abuse that the Vedas had made of primitive traditions, he first applied himself to drawing from them texts to fight the Brahmins with their own weapons. “Since their Vedam is in our hands, we have extracted texts suitable to convince them of the fundamental truths which ruin idolatry. Indeed the unity of God, the character of the true God, the salvation and reprobation are in the Vedam; but the truths which are to be found in this book are only spread there like gold spangles on heaps of sand: for the rest we find there the principle of all the Indian sects, and perhaps the details of all the errors which form their body of doctrine."

One of the first investigations of the fruits of P. Calmette was to have been sent to Paris a copy of the four Vedas, written about ____. Here is the occasion.

The King's Library was not yet very large, when Abbé Bignon was appointed curator in 1718, and this scholar brought there his own library, which was already very fine, and with it a great desire to enrich the royal establishment which he held and was entrusted. It was the time when we began to deal in France with the ancient religions of India and Persia. We spoke especially of certain sacred books, which went back, it was said, in the highest antiquity, and which deserved by their importance the attention of scientists.

Such curious works were worthy of the Royal Library, and Abbé Bignon, for this precious acquisition, believed that he had nothing better to do than to address himself to Father Souciet, librarian of the college Louis-le-Grand, in frequent correspondence with the missionaries of the East. The P. Souciet, zealous himself to this kind of research, sent an urgent request to Father Le Gac, superior of the residence of Pondicherry. The P. Le Gac replied first that to get an exact copy of the four Vedas would be a very difficult and perhaps an expensive affair; that he did not see too much of what use this copy could be in Paris, since there would be no scientist able to decipher it; that however he was going to take care of it seriously. If there was some hope of obtaining certified copies of the Vedas, it was through the medium of P. Calmette.

It was to him that indeed turned the P. Le Gac, and the deal was finalized, despite enormous difficulties. Here is what the P. Calmette said:

"Those who write that for thirty years the Vedam is not found are not entirely wrong: money was not sufficient for the find. It seems to me that we would never have had it, if we had not, among the Brahmins, hidden Christians who trade with them without being known to be Christians. It is to one of them that we owe this discovery, and there are two of them now who are busy researching the books and having them copied. If we came to know that it is for us, we would do serious business with them, especially on the subject of Vedam; it is an article that cannot be forgiven."

"On the thought so found, that many people would not agree in Pondicherry, whether it was the real Veda, and I was asked if I had considered, but the tests I made leave no doubt, and I still do every day when scholars or young Brahmins who learn the Vedam in the schools of the country come to see me, making them recite, and sometimes myself reciting with them, what I have learned from the beginning or elsewhere. This is the Veda, there is no doubt about that."

"It seems to me that we would never have obtained it, if we had not among the bramins a number of hidden Christians, who have regular contact with them without being recognized as Christians. It is to one of these that we owe this discovery, and at present there are two of them, searching for books or trying to copy them. If they found out that they were doing it for us, they would suffer terribly, especially when it comes to the Vedam. It is a thing that would not be forgiven."

-- Ezourvedam: A French Veda of the Eighteenth Century, Edited with an Introduction by Ludo Rocher

So, thanks to Father Calmette and several Christian Brahmins, the P. Le Gac could write in 1732 to Fr. Souciet:

"The four books that contain the Vedas are an expense of 35 to 40 pagodas (about 350 francs). I have already sent two for the Library of SM. We are working on transcribing the other two."

The copy of the four Vedas, sent to Paris the following year, was deposited in the Richelieu Library, department of manuscripts, where it is still found.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF FRANCE [BIBLIOTHEQUE NACIONAL DE FRANCE] https://www.bnf.fr/fr

YOUR SEARCH: VEDAS 1045 RESULTS

https://ccfr.bnf.fr/portailccfr/jsp/pub ... all_simple

[OF 1045 VEDA RESULTS, ZERO 1732-33 LE GAC/CALMETTE VEDAS RESULTS FOUND]

If the learned P. Calmette had done nothing else than to obtain, by dint of zeal and industry, this unexpected result, he would already deserve great praise. To have made a first breach in the great wall of the Brahmins, his name should be inscribed with honor at the head of the Indianists. Among the Romans, there was a special crown for the soldier who climbed the first ramparts of a besieged city; the work of Father Calmette is comparable to the taking of a citadel.

It must be confessed, that the P. Le Gac had predicted what happened: this package in the Royal Library was first perfectly useless, and soon the souvenir was cleared. Some of the manuscripts were curious enough to show several Vedas written on palm leaves in Telingas characters. But we did not know the origin, and no Indianist was tempted to use it. It is to these books that Voltaire's mischief could rightly apply:

"Sacred they are, because no one touches them."

However, the taste for oriental studies gained consistency at the beginning of this century, and this mysterious copy of the Vedas contributed perhaps as much to it as the other oriental manuscripts which had been acquired. In 1815 a chair of Sanskrit was erected in Paris in favor of Léonard de Chézy. This famous orientalist, true founder of the Sanskrit school in France, alludes to the copy of the Vedas, when he says, when speaking of the efforts he had been made obliged to do to learn the knowledge of Indian languages:

"The rich treasure of Indian manuscripts that I had constantly before my eyes, those long palm leaves, depositories of the highest thoughts of philosophy, and which, silent for so long, seemed to require an interpreter, excited more and more my curiosity."

So spoke the most laborious of our Indianists. We know that his works, together with those of his worthy successor, Eugène Burnouf, gave great importance to the study of Sanskrit, not only in Paris, but also in the provinces. Honor to Father Calmette, laborious promoter of this movement of minds.

His discovery of the Vedas, and the copies he obtained through the converted Brahmins, were only a prelude. Soon the knowledge he had acquired made him suspect that behind these penetralia of Sanskrit literature, other poems, and even, as he confidently announced, real treasures unknown to him could be found. He said when speaking of Darma shastra:

"If the gentlemen of the Royal Library continue to honor us with the care of finding books, I hope that we will discover riches worthy of Europe. It is not pure gold; it is like that which one draws from mines, where there is more earth than gold. But the glare that certain passages give makes us believe that there really is gold."

This is how he discovered, in addition to several shastras, Upa-Vedas, or commentaries on the Vedas, and Puranas, poems more extensive than the Iliad and which, like the Iliad among the Greeks, contain all the sources of mythology.

This zeal of investigation was shared by his colleagues, and soon the residence of Ballapouram also became a kind of academy, where the Jesuit missionaries, in perfecting the knowledge of the Brahminic books, drew from them weapons to fight the errors.

But not content with a philosophical war, and wanting to join his arguments another way entirely consistent with the genius of these peoples, the P. Calmette conceived a design that then no one else was capable of. We read in his correspondence that he also began to compose poems himself, like the Brahmins, to refute their fictions. Surprisingly, a poor religious man, without grammar, without dictionary, made, more than a century ago, enough progress in the language of the Vedas, to accomplish a work which the Indianists of India would scarcely dare to undertake today.

It is curious to see what such extraordinary poetic inspiration has produced. The one of these poems which obtained a certain celebrity by a circumstance of which we will speak later is called Ezour-Vedam. We must say a word about it.

The form adopted by the P. Calmette, similar to that of the Brahminic Vedas, is that of dialogue. A missionary and a Brahmin, under ancient names, speak in turn, the Brahmin to expound his ideas from the Vedas and the Puranas, and the missionary to refute them. So that, if we suppose with the missionary that Indian superstitions come from primitive traditions altered by ignorance, or by the taste for fables, and if we attribute to the word Veda its true meaning of "revelation," we will have the abridgment of all the work of the missionary saying:

"There was a Veda, an early revelation, and the tradition has come down to The Indies; but you brahmins have corrupted the Veda with errors of all kinds. These errors, I come to destroy them. Soumanta, touched by the unhappy fate of men who all given over to error and idolatry, blindly ran to their ruin, formed the design of enlightening and saving them."

To dispel therefore the thick darkness which had obscured their reason, he composed Ezour-Vedam, where, recalling them to their very reason, he made them know and feel the truth which they had abandoned to indulge in idolatry. So begins the Ezour-Vedam, such is the purpose of the missionary and the subject of all that he delivered.

To enter into the matter, the author assumes that Vyasa, eager to learn and to achieve salvation, comes to find Soumanta, and thus addresses him:

"The unhappy century in which we live is the century of sin: corruption has become general. It is a boundless sea that has swallowed everything up. We hardly see a small number of virtuous souls floating around. All the rest has been drawn away; everything has been corrupted. Plunged myself, like the others, in this ocean of iniquities, of which I neither discover the edges nor the deep down, I cannot fail to perish like them. Give me a helping hand, and like a skilful pilot, pull me out of this abyss to lead me happily to port."

And a little further:

"You see at your feet a sinner who is only seeking to learn; serve me, therefore, as guide and father; save my soul by delivering it from its mistakes."

Soumanta replied:

"Since when did he come to you in the spirit of wanting to teach you the Vedas, and you become virtuous? Was it not you who invented this prodigious number of Puranas, contrary in everything to Vedam, and to the truth, and which were the unfortunate principle of idolatry and error? You have done more: you have invented several incarnations that you attribute to Vishnu. You maintained the world in these reveries, and you have succeeded in making them taste .... You have made men forget even the very name of God. You have plunged them into idolatry. How to defeat them today? They have your books in their hands all the time; they will not leave them. If I come to teach you today about the truth, what fruit will they reap? Is there an appearance that I can manage to make her taste and love?"

At these words, Vyasa is humbled, and still admits he is the greatest of sinners, and begs his new master to forget everything and think only of the rescue.

Responds Soumanta:

"I will rescue you, but on condition that you will throw in the fire all the books that you have composed; that you will give up your prejudices, etc."

Then the missionary, under the mantle of the Indian doctor, reviews the fables invented by Vyasa, sometimes by reproaching him, sometimes by answering his questions and dispelling the prejudices of his mind. Here are a few features.

“The sun you have made deified is just a lifeless, unconscious body. He is in the hands of God, like a torch in the hands of a man, created by him to light up the world; he obeys his voice and spreads his light everywhere, like a torch which begins to light up as soon as it is lit."

"You gave the figure of man to the sun, the moon, the stars; ___ done animated beings; it is a pure lie and proof of your ignorance. These inanimate beings are created by God to enlighten the world." [Ezour-Vedam 1. 1, c. VII]

"The Ganges has more virtues than another river, what do you get in? the Ganges water as the fountain, like the Creek, which washes away sins, it is the repentance have committed, it is a good practice for future.”

We see that the two interlocutors of Ezour-Vedam are Vyasa, the famous compiler of fables, the Homer of the Indians who is to be converted, and Soumanta who fulfills the role of missionary. It is useless to follow Soumanta in the series of his refutations. These passages taken at random can give a fair idea of the Christian role he fulfills with regard to Vyasa.

The greatest obstacle to the conversion of the Brahmins was not so much in their errors, which they sometimes readily recognize, as in the demands of their proud caste. But the invasion and domination of the Mughals in the Carnate had the double advantage of protecting the missionaries, and greatly weakening the tyranny of customs.

Soumanta alludes to this circumstance. He said:

"However, despite the evils which flood the earth in this unhappy century, one can say that he has something more advantageous than the others. Vyasa, what are these advantages? In the first centuries, each caste was subject to different ceremonies that are no longer of usage. One did not think to teach the Veda to Choutres and the populace; it would have been a sin is the can now without fear or scruple."

The P. Calmette probably wants to speak of Christian revelation; and this was in fact the great innovation introduced then in the Indies by the Roman brahmins.

We can read in the Edifying Letters the astonishing successes of their apostolic enterprise.

The Sama-Veda is another sacred book of the Brahmins, that P. Calmette wanted to make an imitation of; it was also a manuscript in the library of Pondicherry. The Sanskrit text was in European characters like that of Ezour-Vedam, with the French translation opposite. This work had for its object the creation of the world, and the refutation of the emblematic fables, which are like the foundation of Indian mythology. I mean the Avatars or Incarnations of Vishnu. The dialogue is between Narayan, author of the Brahminic Sama-Véda, and Djaimini, author of the Christian Sama-Véda. The beginning resembles that of Ezour-Vedam:

"Djaimini, touched with compassion, and eager to save men, who in this century of sin had had false ideas of the divinity, undertakes to recall them to the knowledge of the true God, by retracing in their eyes what constitutes his essence."

Then invocation and dedication of the book to the Supreme Being. Narayan, who had heard of the different metamorphoses of the divinity, and who had given thought to all these reveries, presents himself with his hands joined before Djaimini, the master of Vedam, and says to him:

“I am, Lord, a man completely given over to error. I address myself to you as to the most enlightened of all men, to beg you to teach me the road which I must follow henceforth to ____."

The story, as we can the see, is quite simple. Djaimini first tries to give a fair idea of the true God, and the worship that should be rendered to him, and he condemns the worship that Narayan wants us to render to Vishnu. Then comes a series of chapters in five books, which in turn exposes one of Narayan incarnations of Vishnu, and Djaimini the rejects.

The Sanskrit text, as I said earlier, is in European characters, in favor of those who are not familiar with the Telinga character. An English author of whom I will have to speak shortly, for proving that it is pure Sanskrit, shows that there is no other difference there than that of the pronunciation of the carnate; he takes, for example, the beginning of the Sama-Veda, as the missionary wrote it, and he gives a correct transcription, where there is almost no other change than that of the vowels. We will only quote the first verse.

The missionary had written, according to the pronunciation of the carnate: Poromo kariniko zaimeni koli kolmocho, etc. The English author shows that it is pure Sanskrit, by making some small changes which are due to the pronunciation: Parama carinico jaimenih cali calmasha, etc. For European characters, it would be easy to substitute the devanagari character, and everything would be perfect.

At the same time, in the Maduré mission, the P. Beschi was famous for his poems and for his grammars and dictionaries, many of which were printed by the Asiatic Society of Madras and the Danish mission of Tranquebar. The main work of Father Beschi is the Tambâvani, a sacred poem as voluminous as the Iliad, and intended to bring evangelical history within the reach of Indian imaginations. "In this work," says the learned orientalist Klaproth, "the ____ Innocents massacre is regarded by the natives of Madurai as the most beautiful piece that exists in their language."

Another book that the P. Beschi composed, but prose, is called Veda-Vilakkam, which means "Light of the Gospel." It is an exposition of the Catholic faith. "The P. Beschi," still says Klaproth, "was generally esteemed for his piety, kindness and expertise. He was mainly concerned with the conversion of idolaters, and his zeal was rewarded with extraordinary success. "

Let us return to Fr. Calmette.

This kind of polemic, designed by the P. Calmette, and continued by several of his colleagues, has perhaps not had much power for the conversion of the Brahmins, but it is undoubtedly this which gave birth to other compositions of a completely different kind, and more effective, in my opinion, to strike the spirit of the Hindus.

The great obstacle was a blind respect for the person of the Brahmins. It occurred to the missionaries to use the weapon of ridicule against them, and they put French causticity to use. We owe Father Dubois the knowledge of a collection of pleasant tales which could only be composed by the missionaries. Such is, for example, a tale entitled: "The Four Mad Brahmins." One cannot imagine a more malicious or more amusing criticism of Brahminic vanity.

The author supposes that four Brahmins traveling together were greeted respectfully by a man of the military caste. "It is me he wanted to greet," said one of the four a little further on. "No, it's not you, it's me," said another. And on this great dispute, Chacun claims that it alone is that the salvation was addressed. To end the dispute, the party decides that the wisest thing is to run after the military man and to question him himself.

The latter, seeing what sort of people he was dealing with, wanted to amuse himself at their expense. "He's the craziest of the four I claimed to greet," he replied, and continued on his way.

But the four Brahmins did not stop there; they had the salvation of the soldier so strongly at heart that, in order to have the honor of it, each of them claimed to surpass the others in madness. As they would not yield on this point more than the other, the party decided to bring the case before the judges of the neighboring town. And so begins the most laughable trial that has ever been pleaded in any court. The comic detail is matched only by the even more comical gravity of the judicial form, and should be read in the Abbe Dubois, four speeches where every Brahmin, by the story of some trait of his life, seeks to demonstrate that he is crazier than the others.

If we want to put a stop to philosophy, and relax from the application that the subtlety of Indian metaphysics sometimes requires, read a work by Father Beschi entitled: "Les Aventures du guru Paramarta," which we must also owe the translation to M. l'Abbé Dubois. This guru, a model of simplicity, had five disciples, who called themselves: the first Stupid, the second Idiot, the third Dazed, the fourth Onlooker, and the fifth Heavy. As we see, it is only a charge, a story without verisimilitude, in which the author, to amuse his readers, and to ridicule popular prejudices, has combined the most laughable traits of silliness and stupidity.

Such tales are not worthy of appearing among the titles of glory of a nation, but they serve admirably to make known its genius and its customs, and the history of the missions must mention them, even if it loses a little of its seriousness.

And who could help laughing at the guru and his disciples crossing a river to test with a brand if she was asleep, for they had heard it said that it was dangerous to walk through her when she was awake; or else, seeing the credulity of Onlooker, to whom a joker takes a mare's egg for a pumpkin; then the driver who wants to pay the shadow of his ox; then the angled horse, etc.? What is surprising is that these silly disciples sometimes rediscover common sense and eloquence. But then their mind is perhaps even more laughable.

So after crossing the river, they imagined that one of them was swallowed up; for he who counted the others forgot to count himself, and they were only five instead of six. Then they uttered lamentable cries as at the death of a friend or a relative. After exhaling their first pain, they all turned to the side of the river and apostrophized unanimously:

"Merciless river," they cried, "damn river! more cruel and more treacherous than the tigers of the forests. How dare you swallow up a disciple of the great Paramarta? This famous character, whose name is so revered, of this holy man to whom all pay a tribute of esteem and admiration? After such a trait of perfidy, who will dare henceforth to set foot in your waters?"

From reproaches they passed to imprecations.

Said one:

"May I see your source dry up! May your bed dry up without leaving a single vestige that announces to future races that you were once a river!"

Said another,

"May the fish and the frogs which swim in your waters, devour you all alive so as to make you as dry as the sand of your banks!"

Said a third one:

"May there be a general drought. May the sky not let a drop of rain escape for three years, so that the springs, which have dried up to the last, do not send you a single drop of water! May I see the flies and ants walking around on your bed and insulted with impunity!"

Said a fourth:

"May you be devoured by the fire from your source to your mouth!"

And the last one:

"May you disappear. May your bed in future contain only stones, brambles and thorns!"

These charges obviously originated in Europe, and there are such pleasant stories that are still told every day in our countryside.

A tale as facetious as the others, but of a moral more profound, is that of the minister Appadji, who, to teach the king his master a wise lesson, made a stupid shepherd play the role of Sannyasi. It is an excellent review of the prejudices of the Indians, and of the charlatanism of some Brahmins.

But it's time to stop. It is enough for us to have noted among the Indians the existence of a multitude of very entertaining tales of which we already have good translations. Despite the apparent frivolity of this kind of work, they cannot fail to please in Europe. M. l'Abbe Dubois was astonished to have encountered in the depths of Indostan popular tales very widespread in several provinces of France. There is nothing in this which should be surprising, if we consider that the Indies owe their knowledge only to French missionaries.

We need not relate here either the successes then obtained by the two missions of the Carnate and the Maduré, nor the storm which arose against them from the bosom of the very Christian kingdom, and which ruined such fine hopes. In 1841, I saw in the archives of the kingdom (K. 1284) minutes signed Lauriston. These are the inventories, made by order of the government, of all the movable and immovable property of the missionaries. Sad reading! A table, a chair, a candlestick, two or three old books, and a few manuscripts -- that was all their cells contained. These miserable remains of their apostolate enriched no one, and idolatry alone had to rejoice in the extinction of the Jesuits. As for the small number of books and manuscripts left by them, they were deposited in the library of Foreign Missions in Pondicherry. Barely a few years had passed that in Paris no one any longer cared for missionaries, Indianists or Brahmins.

But one day, a member of the Council of Pondicherry arrived in Paris, declared himself the possessor of a precious manuscript. It was nothing less than a Vedam, and because of its importance, it was made a present to the King's Library. Let us hear Voltaire report on this event.

“A happier chance has procured at the Library of Paris an old book of the Brahmins; it is the Ezour-Vedam, written before the expedition of Alexander to India, with a ritual of all the ancient rites of the Brahmans, entitled the Cormo-Vedam. This manuscript, translated by a Brahmin, is not in truth the Vedam himself, but it is a summary of the opinions and of the titles contained in this law."

"Abbé Bazin, before dying, sent to the King's Library the most precious manuscript in all the East; it is an old comment from a Brahmin named Chumontou on the Vedam, which is the sacred book of the ancient Brahmins. This manuscript is undoubtedly from the time when the ancient religion of gymnosophists began to be corrupt; it is, after our sacred books, the monument the most respectable of the claim of the unity of God; it is entitled Ezour-Vedam, as it were the true Veda explained, the pure Vedam. There can be no doubt that it was written before Alexander's expedition."

"When we assume that this rare manuscript was written about four hundred years before the conquest of part of India by Alexander, we will not stray too far from the truth."

Voltaire adds elsewhere that this precious book was translated from Sanscretan by the high priest or archbrahme of the pagoda of Chéringam, an old man respected for his incorruptible virtue, who knew the French, and who rendered great service to the East India Company [Philosophy of History, c, XVII. Century of Louis XIV, c. XxIx.]. It was not without ulterior motives that our philosopher took pleasure in praising this work and in supposing that it was so ancient: this little stratagem suited the war he was waging on our holy books.

Even today, and with a very different intention, another school invoked the testimony of Ezour-Vedam as that of a Brahminic work. The Essay on the indifférence quotes lyrics showing the existence of Christian ideas to the Indians long before the Christianity. Thus Ezour-Vedam was in possession of a distinguished honor of which its author had hardly dreamed, and although this book does not entirely correspond to the idea that one should form Brahmanism, it was considered to be a sacred book, when suddenly the Asian Research of Calcutta let Europe know that this alleged Vedam is the work of a Jesuit missionary.

"An English orientalist, who happened to be in Pondicherry, having obtained permission to visit the library of Foreign Missions, had discovered the original of the Ezour-Vedam there, along with several other manuscripts of the same kind. Great rumor among scholars! This is how we were mystified! A Jesuit missionary made us take his work for a sacred book of the Brahmans! To deceive all of Europe, what a darkness! And here is another deception added to the others, in the history of the Society of Jesus."

This new crime was denounced to the public with the usual justice and indignation. What embarrassed the critics a little is that the author of these Vedas spoke of the four Vedas of the Brahmins to refute them: he said their origin; he gave the names of their authors.

Said M. Langles:

"It is an inexplicable thing, the missionary was not afraid to insert in his work which was capable of a convincing impostor. There is perhaps something more inexplicable still, it is that men of wit and taste allow themselves to be dominated by their prejudices to the point of closing their eyes to the evidence."

What embarrassed the critics a bit was that the author of the Pseudo-vedas spoke of the four vedas of the brahmins to refute them; he described their origin and even gave the names of their authors. "It is something inexplicable," said M. Lanjuinais, "that the missionary [who wrote the Ezour-vedam] did not shy away from inserting in his work what could convict him of his imposture." (Bach 1848:63)

-- Anquetil-Duperron's Search for the True Vedas, Excerpt from The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

Mr. Ellis, after listing the books he had found, missionary wondered what could have been the author, and he expressed the opinion that it was probably the P. Robert de Nobili; but he spoke by guesswork, and because he knew vaguely that once the P. Nobili had adopted the way of life of Brahmins. This assumption can in no way be justified. The P. Nobili was the Portuguese mission of Madura where they spoke the Tamil, and Ezour-Vedam, with other similar works, was composed for the French mission of the Carnatic, where they spoke a language quite different, the telinga. The Sanskrit text of these works, written in European characters, is expressed there with the pronunciation of the telinga, and the French translation which is opposite, says the Asiatik Researches, is by the same hand as the text.

Finally, the original manuscripts were found in the library of the French Seminary of Foreign Missions, in Pondicherry. In the time of Fr. de Nobili, Pondicherry did not exist, or was only a hamlet. It was only in the 18th century that the French having built a town there, it became the center of the new Carnate mission.

What I said above already made me suspect that not only the Ezour-Vedam was a French work, but that the P. Calmette was the author. To acquire the certainty I had thought to speak to that, all of Paris, was the better to know the status of the issue. The venerable Abbé Dubois, who was a missionary for forty years in India, who lived with the last Jesuit missionaries, and who lived in Pondicherry, has no doubt seen, I said to myself, those curious manuscripts which made so much noise. I went on to find, and without letting him know my opinion, I asked him if we knew the author of the Ezour-Veda. "This is the P. Calmette," he told me at once. But, he added, several missionaries got their hands on it. I needed no more. I had rediscovered the trace of the illustrious Indianist who was the initiator of French scholars in this branch which is so flourishing today.

See Asiatick Researches, t. XIV.

J. BACH.