by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/15/20

Guillaume Emmanuel Joseph SAINTE CROIX (de)

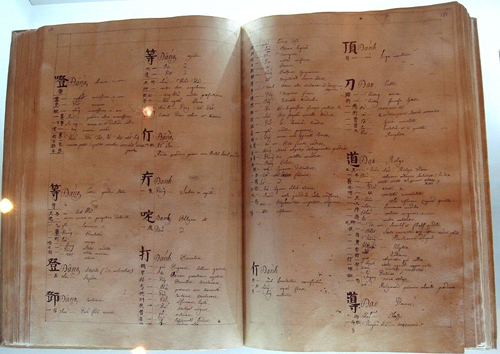

The Ezour-Vedam or Old Commentary on Vedam. Containing the exhibition of religious and philosophical views of Indians. Translated from Samscretan by a Brame.

In the Imprimerie de M. de Felice, Yverdon 1778, in-12 (9.5x16cm), xij 13-332pp. and 264pp., 2 bound volumes.

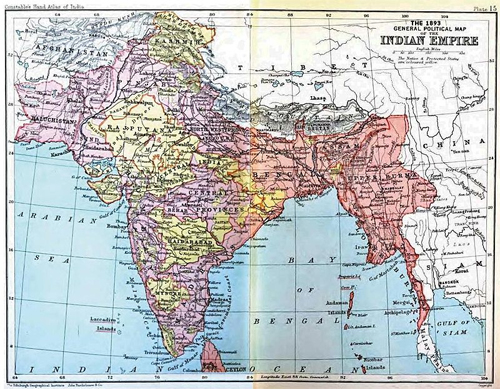

First edition of this religious pastiche composed by Jesuit missionaries in India. Printed on the presses of Fortune Barthelemy Felice in Yverdon, it was published by the Holy Cross baron.

Binding post (1840) full fair calf. Back with five nerves decorated with gilded boxes and nets, as well as parts of title and volume number of long grain brown morocco. Triple gilt fillets in coaching contreplats. Quadruple threads and golden floral spandrels framing of paper contreplats to the tank. All edges gilt.

Pretty nice copy binding Niédrée, whose name is registered in pen on the first guard of the first volume.

-- Guillaume Emmanuel Joseph SAINTE CROIX (de), by EditionOriginale.com

Fortunato Bartolomeo de Félice

Count di Panzutti

Born: Fortunato Bartolomeo de Félice, Rome, Italy

Nationality: Italian

Occupation: Nobleman, Author, Scientist

Spouse(s) Agnese Arcuato, Countessa di Panzutti (m. 1759)

Children: 13

Parent(s): Gennaro de Félice and Catarina Rossetti

Website: http://de-felice.org/

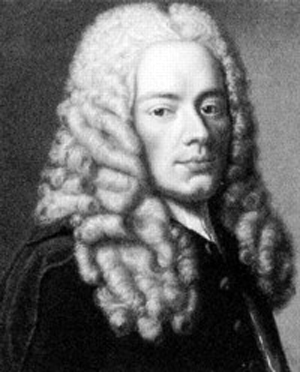

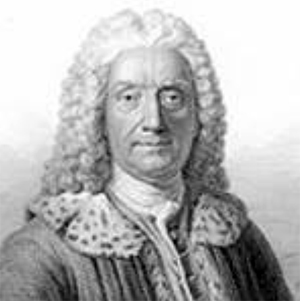

Fortunato de Felice

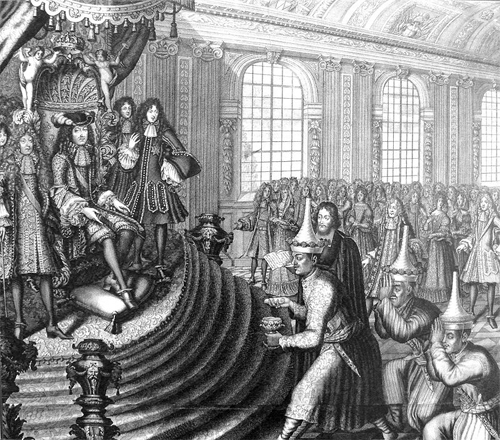

Fortunato Bartolomeo de Felice (24 August 1723 – 13 February 1789), 2nd Comte de Panzutti, also known as Fortuné-Barthélemy de Félice and Francesco Placido Bartolomeo De Felice, was an Italian nobleman, a famed author, philosopher, scientist, and is said to have been one of the most important publishers of the 18th century.[1] He is considered a pioneer of education in Switzerland, and a formative contributor to the European Enlightenment.

Life

Fortunato Bartolomeo de Félice was born in Rome to a Neapolitan family as the eldest of six children on 24 August 1723. He was confirmed in 1733 in the parish of St. Celso e Giuliano. At the age of 12, he studied at Rome and Naples under the Jesuits, taught by the Franciscan Fortunato da Brescia.

On 28 May 1746 he was ordained by papal dispensation, whilst also teaching philosophy. Through his studies at the monastery of San Francesco in Ripa, he discovered a love of Physics, becoming friends with Celestino Galiani. In 1753, Galiani appointed de Félice chair of Ancient and Modern Geography, and the chair of experimental physics and mathematics at Naples University. There he became friends with the Prince Raimondo di Sangro...

Raimondo di Sangro, Prince of Sansevero (30 January 1710 – 22 March 1771) was an Italian nobleman, inventor, soldier, writer, scientist, alchemist and freemason best remembered for his reconstruction of the Chapel of Sansevero in Naples...Its origin dates to 1590 when John Francesco di Sangro, Duke of Torremaggiore, after recovering from a serious illness, had a private chapel built in what were then the gardens of the nearby Sansevero family residence, the Palazzo Sansevero. The building was converted into a family burial chapel by Alessandro di Sangro in 1613 (as inscribed on the marble plinth over the entrance to the chapel). Definitive form was given to the chapel by Raimondo di Sangro, Prince of Sansevero, who also included Masonic symbols in its reconstruction. Until 1888 a passageway connected the Sansevero palace with the chapel...

The chapel houses almost thirty works of art, among which are three particular sculptures of note. These marble statues are emblematic of the love of decoration in the Rococo period and their depiction of translucent veils and a fisherman's net represent remarkable artistic achievement.

The Veiled Truth (Pudicizia, also called Modesty or Chastity) was completed by Antonio Corradini in 1752 as a tomb monument dedicated to Cecilia Gaetani dell'Aquila d'Aragona, mother of Raimondo...

The original floor (most of the present one dates from 1901) was in black and white (said to symbolize good/evil) in the design of a labyrinth (a masonic symbol for "initiation")...

Head of the male model

The chapel also displays two early examples of what was long thought to be a form of plastination in its basement. ].. The exhibit consists of a mature male and a pregnant woman. Their skeletons are encased in the hardened arteries and veins which are colored red and blue respectively.

-- Cappella Sansevero, by Wikipedia

From the age of ten he was educated at the Jesuit College in Rome...

In 1730, at the age of 20, he returned to Naples. He became a friend of Charles Bourbon, who became king of Naples in 1734, for whom he invented a waterproof cape.

In 1744 he distinguished himself at the head of a regiment during the Battle of Velletri, in the war between the Habsburgs and the Bourbons. While in command of the military he built a cannon out of lightweight materials which had a longer range than the standard ones of the time, and wrote a military treatise on the employment of infantry (Manuale di esercizi militari per la fanteria) for which he was praised by Frederick II of Prussia.

His real interests, however, were the studies of alchemy, mechanics and the sciences in general. Among his inventions were:

• An hydraulic device that could pump water to any height

• An "eternal flame", using chemical compounds of his own invention

• A carriage with wood and cork "horses" which, driven by a cunning system of paddlewheels, could travel on both land and water

• Coloured fireworks

• A printing press which could print different colours in a single impression.

The Prince spoke several European languages, as well as Arabic and Hebrew. After returning to Naples he set up a printing press in the basement of his house where he printed both his own works and those of others, some of which he translated himself. As some of these were censored by the ecclesiastical authorities he also wrote anonymously. Some of his publications were clearly influenced by Freemasonry, and he communicated with fellow masons such as the Scot Andrew Michael Ramsay, whose Voyages of Cyrus he translated and published, and the English poet Alexander Pope, whose Rape of the Lock he translated and published (although, due to condemnations by the Jesuits, he had to deny these activities). He was head of the Neapolitan masonic lodge until he was excommunicated by the Church, making an enemy of the Neapolitan cardinal Giuseppe Spinelli. The excommunication was later revoked by Pope Benedict XIV, probably on account of the influence of the di Sangro family.

Whilst in Naples, he forged a friendship with Fortunato-Bartolommeo de Félice, 2nd Count di Panzutti, who had been appointed chair of experimental physics and mathematics at Naples University by Celestino Galiani and later set up the famous publishing press at Yverdon in 1762. Together the Prince and the Count translated the physicist John Arbuthnot's works from Latin.

Many legends grew up around his alchemical activities: that he could create blood out of nothing, that he could replicate the liquefaction of blood of San Gennaro, that he had people killed so that he could use their bones and skin for experiments. The Chapel of Sansevero was said to have been constructed on an old temple of Isis, and di Sangro was said to have been a Rosicrucian. To justify this, locals pointed to a massive Statue of the God of the Nile, located just around the corner from his home.

To add to the sense of dread, di Sangro's family home in Naples, the Palazzo Sansevero, was the scene of a brutal murder at the end of the 16th century, when the composer Carlo Gesualdo caught his wife and her lover in flagrante delicto, and hacked them to death in their bed.

The last years of his life were dedicated to decorating the Chapel of Sansevero with marble works from the greatest artists of the time, including Antonio Corradini, Francesco Queirolo, and Giuseppe Sanmartino (whose Veiled Christ's detailed marble veil was thought by many to be created by di Sangro's alchemy) and preparing anatomical models. Two of the models, known as anatomical machines, are still on display in the Chapel, and have given rise to legends as to how they were constructed (even today the exact method is not known). Until recently many Neapolitans believed that the models were of his servant and a pregnant woman, into whose veins an artificial substance was injected under pressure, but the latest research has shown that the models are artificial.

He destroyed his own scientific archive before he died. After his death, his descendants, under threat of excommunication by the Church due to di Sangro's involvement with Freemasonry and alchemy, destroyed what was left of his writings, formulae, laboratory equipment and results of experiments.

Raimondo di Sangro died in Naples in 1771, his death being hastened by the continuous use of dangerous chemicals in his experiments and inventions.

-- Raimondo di Sangro, by Wikipedia

who aided him in his translation of the physicist John Arbuthnot's works from Latin.

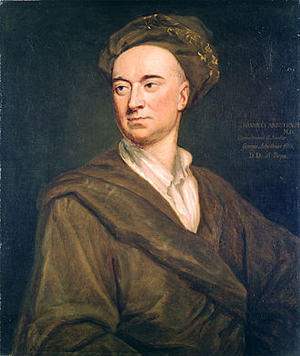

John Arbuthnot FRS (baptised 29 April 1667 – 27 February 1735), often known simply as Dr Arbuthnot, was a Scottish physician, satirist and polymath in London...

In 1702, he was at Epsom when Prince George of Denmark, husband of Queen Anne fell ill. According to tradition, Arbuthnot treated the prince successfully. According to tradition again, this treatment earned him an invitation to court. Also around 1702, he married Margaret, whose maiden name is possibly Wemyss. Although there are no baptismal records, it seems that his first son, George (named in honour of the prince), was born in 1703. He was elected to be a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1704. Also thanks to the Queen's presence, he was made an MD at Cambridge University on 16 April 1705.

Arbuthnot was an amiable individual, and Swift said that the only fault an enemy could lay upon him was a slight waddle in his walk. His conviviality and his royal connections made him an important figure in the Royal Society. In 1705, Arbuthnot became physician extraordinary to Queen Anne, and at the same time was put on the board trying to publish the Historia coelestius. Newton and Edmund Halley wanted it published immediately, to support their work on orbits, while John Flamsteed, the Royal Astronomer whose observations they were, wanted to keep the data secret until he had perfected it. The result was that Arbuthnot used his leverage as friend and physician to Prince George, whose money was paying for the publication, to force Flamsteed to allow it out, albeit with serious errors, in 1712. Also as a scholar, Arbuthnot took up an interest in antiquities and published Tables of Grecian, Roman, and Jewish measures, weights and coins; reduced to the English standard in 1705, 1707, 1709, and, expanded with a preface (which indicated that his second son, Charles, was born in 1705), in 1727 and 1747...

As a Scotsman, Arbuthnot served the crown by writing A sermon preach'd to the people at the Mercat Cross of Edinborough on the subject of the union. Ecclesiastes, Chapter 10, Verse 27. The work was designed to persuade Scots to accept the Act of Union. When the Act passed, Arbuthnot was made a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. He was also made a physician in ordinary to the Queen, which made him part of the royal household.

Arbuthnot returned to mathematics in 1710 with An argument for Divine Providence, taken from the constant regularity observed in the births of both sexes (linked below) in the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions. In this paper, Arbuthnot examined birth records in London for each of the 82 years from 1629 to 1710 and the human sex ratio at birth: in every year, the number of males born in London exceeded the number of females. If the probability of male and female birth were equal, the probability of the observed outcome would be 1/282, a vanishingly small number. This is vanishingly small, leading Arbuthnot that this was not due to chance, but to divine providence: "From whence it follows, that it is Art, not Chance, that governs." This paper was a landmark in the history of statistics...

In 1712, Arbuthnot and Swift both attempted to aid the Tory government of Harley and Henry St. John in their efforts to end the War of the Spanish Succession. The war had profited John and Sarah Churchill, and the Tory ministry sought to end it by withdrawing from all England's alliances and negotiating directly with France. Swift wrote The Conduct of the Allies, and Arbuthnot wrote a series of five pamphlets featuring John Bull. The first of these, Law Is a Bottomless Pit (1712), introduced a simple allegory to explain the war. John Bull (England) is suing Louis Baboon (i.e. Louis Bourbon, or Louis XIV of France) over the estate of the dead Lord Strutt (Charles II of Spain). Bull's lawyer is the one who really enjoys the suit, and he is Humphrey Hocus (Marlborough). Bull has a sister named Peg (Scotland). The pamphlets are Swiftian in their satire, in that they make all of the characters hopelessly flawed and comic and none of their endeavour worth pursuing (which was Arbuthnot's intent, as he sought to make the war an object of scorn), but it is filled with homespun humour, a common touch, and a sympathy for the figures that is distinctly non-Swiftian.

In 1713, Arbuthnot continued his political satire with Proposals for printing a very curious discourse... a treatise of the art of political lying, with an abstract of the first volume. As with other works that Arbuthnot encouraged, this systemizes a rhetoric of bad thinking and writing. He proposes to teach people to lie well...

When George I came to the throne, Arbuthnot lost all of his royal appointments and houses, but he still had a vigorous medical practice...

In 1719 he took part in a pamphlet war over the treatment of smallpox. In particular, he attacked Dr Woodward, who had again presented a dogmatic and, Arbuthnot thought, irrational opinion. In 1723, Arbuthnot was made one of the censors of the Royal College of Physicians, and as such he was one of the campaigners to inspect and improve the drugs sold by apothecaries in London. In 1723, the apothecaries sued the RCP, and Arbuthnot wrote Reasons humbly offered by the ... upholders (undertakers) against part of the bill for the better viewing, searching, and examining of drugs. The pamphlet suggested that the funeral directors of London might wish to sue the Royal College of Physicians as well to ensure that drug safety remained poor. In 1727, he was made an elect of the Royal College of Physicians.

In 1726 and 1727, Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope reunited at Arbuthnot's house during visits, and Swift showed Arbuthnot the manuscript of Gulliver's Travels ahead of time. The detailed parody of on-going Royal Society projects in book III of Gulliver's Travels likely came from "hints" from Arbuthnot...CHAPTER III. A phenomenon solved by modern philosophy and astronomy. The Laputians’ great improvements in the latter. The king’s method of suppressing insurrections.

I desired leave of this prince to see the curiosities of the island, which he was graciously pleased to grant, and ordered my tutor to attend me. I chiefly wanted to know, to what cause, in art or in nature, it owed its several motions, whereof I will now give a philosophical account to the reader.

The flying or floating island is exactly circular, its diameter 7837 yards, or about four miles and a half, and consequently contains ten thousand acres. It is three hundred yards thick. The bottom, or under surface, which appears to those who view it below, is one even regular plate of adamant, shooting up to the height of about two hundred yards. Above it lie the several minerals in their usual order, and over all is a coat of rich mould, ten or twelve feet deep. The declivity of the upper surface, from the circumference to the centre, is the natural cause why all the dews and rains, which fall upon the island, are conveyed in small rivulets toward the middle, where they are emptied into four large basins, each of about half a mile in circuit, and two hundred yards distant from the centre. From these basins the water is continually exhaled by the sun in the daytime, which effectually prevents their overflowing. Besides, as it is in the power of the monarch to raise the island above the region of clouds and vapours, he can prevent the falling of dews and rain whenever he pleases. For the highest clouds cannot rise above two miles, as naturalists agree, at least they were never known to do so in that country.

At the centre of the island there is a chasm about fifty yards in diameter, whence the astronomers descend into a large dome, which is therefore called flandona gagnole, or the astronomer’s cave, situated at the depth of a hundred yards beneath the upper surface of the adamant. In this cave are twenty lamps continually burning, which, from the reflection of the adamant, cast a strong light into every part. The place is stored with great variety of sextants, quadrants, telescopes, astrolabes, and other astronomical instruments. But the greatest curiosity, upon which the fate of the island depends, is a loadstone of a prodigious size, in shape resembling a weaver’s shuttle. It is in length six yards, and in the thickest part at least three yards over. This magnet is sustained by a very strong axle of adamant passing through its middle, upon which it plays, and is poised so exactly that the weakest hand can turn it. It is hooped round with a hollow cylinder of adamant, four feet yards in diameter, placed horizontally, and supported by eight adamantine feet, each six yards high. In the middle of the concave side, there is a groove twelve inches deep, in which the extremities of the axle are lodged, and turned round as there is occasion.

The stone cannot be removed from its place by any force, because the hoop and its feet are one continued piece with that body of adamant which constitutes the bottom of the island.

By means of this loadstone, the island is made to rise and fall, and move from one place to another. For, with respect to that part of the earth over which the monarch presides, the stone is endued at one of its sides with an attractive power, and at the other with a repulsive. Upon placing the magnet erect, with its attracting end towards the earth, the island descends; but when the repelling extremity points downwards, the island mounts directly upwards. When the position of the stone is oblique, the motion of the island is so too. For in this magnet, the forces always act in lines parallel to its direction.

By this oblique motion, the island is conveyed to different parts of the monarch’s dominions. To explain the manner of its progress, let A B represent a line drawn across the dominions of Balnibarbi, let the line c d represent the loadstone, of which let d be the repelling end, and c the attracting end, the island being over C; let the stone be placed in the position c d, with its repelling end downwards; then the island will be driven upwards obliquely towards D. When it is arrived at D, let the stone be turned upon its axle, till its attracting end points towards E, and then the island will be carried obliquely towards E; where, if the stone be again turned upon its axle till it stands in the position E F, with its repelling point downwards, the island will rise obliquely towards F, where, by directing the attracting end towards G, the island may be carried to G, and from G to H, by turning the stone, so as to make its repelling extremity to point directly downward. And thus, by changing the situation of the stone, as often as there is occasion, the island is made to rise and fall by turns in an oblique direction, and by those alternate risings and fallings (the obliquity being not considerable) is conveyed from one part of the dominions to the other.

But it must be observed, that this island cannot move beyond the extent of the dominions below, nor can it rise above the height of four miles. For which the astronomers (who have written large systems concerning the stone) assign the following reason: that the magnetic virtue does not extend beyond the distance of four miles, and that the mineral, which acts upon the stone in the bowels of the earth, and in the sea about six leagues distant from the shore, is not diffused through the whole globe, but terminated with the limits of the king’s dominions; and it was easy, from the great advantage of such a superior situation, for a prince to bring under his obedience whatever country lay within the attraction of that magnet.

When the stone is put parallel to the plane of the horizon, the island stands still; for in that case the extremities of it, being at equal distance from the earth, act with equal force, the one in drawing downwards, the other in pushing upwards, and consequently no motion can ensue.

This loadstone is under the care of certain astronomers, who, from time to time, give it such positions as the monarch directs. They spend the greatest part of their lives in observing the celestial bodies, which they do by the assistance of glasses, far excelling ours in goodness. For, although their largest telescopes do not exceed three feet, they magnify much more than those of a hundred with us, and show the stars with greater clearness. This advantage has enabled them to extend their discoveries much further than our astronomers in Europe; for they have made a catalogue of ten thousand fixed stars, whereas the largest of ours do not contain above one third part of that number. They have likewise discovered two lesser stars, or satellites, which revolve about Mars; whereof the innermost is distant from the centre of the primary planet exactly three of his diameters, and the outermost, five; the former revolves in the space of ten hours, and the latter in twenty-one and a half; so that the squares of their periodical times are very near in the same proportion with the cubes of their distance from the centre of Mars; which evidently shows them to be governed by the same law of gravitation that influences the other heavenly bodies.

They have observed ninety-three different comets, and settled their periods with great exactness. If this be true (and they affirm it with great confidence) it is much to be wished, that their observations were made public, whereby the theory of comets, which at present is very lame and defective, might be brought to the same perfection with other arts of astronomy.

-- Gulliver’s Travels Into Several Remote Nations of the World, by Jonathan Swift, D.D., Dean of St. Patrick's, Dublin

In 1730, Arbuthnot's wife died. The next year, he produced a work of popular medicine, An essay concerning the nature of aliments, and the choice of them, according to the different constitutions of human bodies. The book was quite popular, and a second edition, with advice on diet, came out the next year. It had four more full editions and translations into French and German. In 1733 he wrote another very popular work of medicine called An Essay Concerning the Effects of Air on Human Bodies. As with the former work, it went through multiple editions and translations. He argued that the air itself had to have enormous effects on the personality and persons of humanity, and he believed that the air of locations resulted in the characteristics of the people, as well as particular maladies. He advised his readers to ventilate sickrooms and to seek fresh air in cities.

-- John Arbuthnot, by Wikipedia

After rescuing the imprisoned Countess Panzutti,[2] Félice and his new wife fled to Bern, with the help of his friend Albrecht von Haller, due to religious persecution from the Roman Catholic Church in Rome. He then converted to Protestant.

In 1758, he founded with de:Vincenz Bernhard Tscharner the Typographic Society of Bern, and was an Italian-speaking ( l'Estratto de la europea letterature until 1762) and a Latin (l'Excerptum totius Italicae nec non Helveticae literaturae, to 1766) literary and scientific journal.

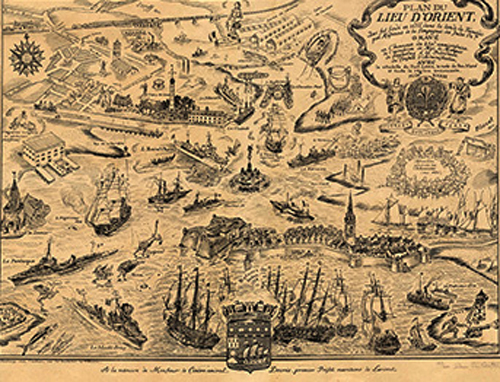

In 1762, after the death of the Countessa di Panzutti to influenza at Tscharner's residence Château Lansitz, he moved to Yverdon where he founded an educational institute for young people from all over Europe and a printing press. The latter quickly developed into one of the most distinguished in Switzerland, producing the Yverdon Encyclopedia, for which he is now famous. In, 1769 he became a citizen of Yverdon and thus Swiss.

He was married four times and had 13 children: in 1756 to Countess Agnese Arcuato, Countessa di Panzutti (1720-1759)[2] (whereby his Earldom was received suo jure, confusing Arcuato's late husband is recorded as the first Count Panzutti), in 1759 to Susanne de Wavre Neuchâtel (1737-1769), in 1769 to Louise Marie Perrelet († 1774), and in 1774 to Jeanne Salomé Sinet.[3]

He died in Yverdon-les-Bains.

Work

De Felice is considered a significant contributor to education in Switzerland. As editor and translator of Burlamaqui's Principes du Droit Naturel, his name became synonymous with natural law throughout Europe. His most important work is the Encyclopédie d'Yverdon, which he headed as editor and for which he wrote more than 800 articles. From 1770 to 1780 he published 58 volumes, and as the Encyclopédie of Paris in a new version of the Protestant perspective.

His other work consists of half a dozen educational, philosophical and scientific books. He translated the works of René Descartes, d'Alembert, Maupertuis and Newton into Italian.

In de Felice's famous printing house, as well as the Encyclopedia, he translated into French works of Elie Bertrand, Charles Bonnet,...

Charles Bonnet (French: [bɔnɛ]; 13 March 1720 – 20 May 1793) was a Genevan naturalist and philosophical writer...

He made law his profession, but his favourite pursuit was the study of natural science. The account of the ant-lion in Noël-Antoine Pluche's Spectacle de la nature, which he read in his sixteenth year, turned his attention to insect life. He procured RAF de Réaumur's work on insects, and with the help of live specimens succeeded in adding many observations to those of Réaumur and Pluche. In 1740, Bonnet communicated to the Academy of Sciences a paper containing a series of experiments establishing what is now termed parthenogenesis in aphids or tree-lice, which obtained for him the honour of being admitted a corresponding member of the academy. During that year he had been in correspondence with his uncle Abraham Trembley who had recently discovered the hydra. This little creature became the hit of all the salons across Europe once philosophers and natural scientists saw its amazing regenerative capabilities. In 1741, Bonnet began to study reproduction by fusion and the regeneration of lost parts in the freshwater hydra and other animals; and in the following year he discovered that the respiration of caterpillars and butterflies is performed by pores, to which the name of stigmata (or spiracles) has since been given. In 1743, he was admitted a fellow of the Royal Society; and in the same year he became a doctor of laws—his last act in connection with a profession which had ever been distasteful to him. In 1753, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and on 15 December 1769 a foreign member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters.

His first published work appeared in 1745, entitled Traité d'insectologie, in which were collected his various discoveries regarding insects, along with a preface on the development of germs and the scale of organized beings. Botany, particularly the leaves of plants, next attracted his attention; and after several years of diligent study, rendered irksome by the increasing weakness of his eyesight, he published in 1754 one of the most original and interesting of his works, Recherches sur l'usage des feuilles dans les plantes. In this book, he observes that gas bubbles form on plant leaves that have been submerged in water, indicating gas exchange; and among other things he advances many considerations tending to show (as was later done by Francis Darwin) that plants are endowed with powers of sensation and discernment. But Bonnet's eyesight, which threatened to fail altogether, caused him to turn to philosophy. In 1754 his Essai de psychologie was published anonymously in London. This was followed by the Essai analytique sur les facultés de l'âme (Copenhagen, 1760), in which he develops his views regarding the physiological conditions of mental activity. He returned to physical science, but to the speculative side of it, in his Considerations sur les corps organisées (Amsterdam, 1762), designed to refute the theory of epigenesis, and to explain and defend the doctrine of pre-existent germs. In his Contemplation de la nature (Amsterdam, 1764–1765; translated into Italian, German, English and Dutch), one of his most popular and delightful works, he sets forth, in eloquent language, the theory that all the beings in nature form a gradual scale rising from lowest to highest, without any break in its continuity. His last important work was the Palingénésie philosophique (Geneva, 1769–1770); in it he treats of the past and future of living beings, and supports the idea of the survival of all animals, and the perfecting of their faculties in a future state...

Bonnet's philosophical system may be outlined as follows. Man is a compound of two distinct substances, mind and body, the one immaterial and the other material. All knowledge originates in sensations; sensations follow (whether as physical effects or merely as sequents Bonnet will not say) vibrations in the nerves appropriate to each; and lastly, the nerves are made to vibrate by external physical stimulus. A nerve once set in motion by a particular object tends to reproduce that motion; so that when it a second time receives an impression from the same object it vibrates with less resistance. The sensation accompanying this increased flexibility in the nerve is, according to Bonnet, the condition of memory. When reflection—that is, the active element in mind—is applied to the acquisition and combination of sensations, those abstract ideas are formed which, though generally distinguished from, are thus merely sensations in combination only. That which puts the mind into activity is pleasure or pain; happiness is the end of human existence.

Bonnet's metaphysical theory is based on two principles borrowed from Leibniz: first, that there are not successive acts of creation, but that the universe is completed by the single original act of the divine will, and thereafter moves on by its own inherent force; and secondly, that there is no break in the continuity of existence. The divine Being originally created a multitude of germs in a graduated scale, each with an inherent power of self-development. At every successive step in the progress of the universe, these germs, as progressively modified, advance nearer to perfection; if some advanced and others did not there would be a gap in the continuity of the chain. Thus not man only but all other forms of existence are immortal. Nor is man's mind alone immortal; his body also will pass into the higher stage, not, indeed, the body he now possesses, but a finer one of which the germ at present exists within him. It is impossible, however, to reach absolute perfection, because the distance is infinite.

In this final proposition, Bonnet violates his own principle of continuity, by postulating an interval between the highest created being and the Divine. It is also difficult to understand whether the constant advance to perfection is performed by each individual, or only by each race of beings as a whole. There seems, in fact, to be an oscillation between two distinct but analogous doctrines—that of the constantly increasing advancement of the individual in future stages of existence, and that of the constantly increasing advancement of the race as a whole according to the successive evolutions of the globe. In Philosophical Palingesis, or Ideas on the Past and Future States of Living Beings (1770), Bonnet argued that females carry within them all future generations in a miniature form. He believed these miniature beings, sometimes called homonculi, would be able to survive even great cataclysms such as the biblical Flood; he predicted, moreover, that these catastrophes brought about evolutionary change, and that after the next disaster, men would become angels, mammals would gain intelligence, and so on.

-- Charles Bonnet, by Wikipedia

Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui,...

Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (French: [byʁlamaki]; 24 June or 13 July 1694 – 3 April 1748) was a Genevan legal and political theorist...

Born in Geneva, Republic of Geneva, into a Calvinist family (descended from the wealthy 16th-century Italian merchant Francesco Burlamacchi of Lucca executed for his Republican sentiments) who had taken refuge religionis causa, he studied law and at 25 he was designated honorary professor of ethics and the law of nature at the university of Geneva. Before taking up the appointment, he travelled through France and England, and made the acquaintance of the most eminent writers of the period...

Burlamaqui's treatise The Principles of Natural and Politic Law was translated into six languages (besides the original French) in 60 editions. His vision of constitutionalism had a major influence on the American Founding Fathers: "Early American thought also drew on ideas circulating on the Continent. The author who played the greatest part in transmitting those ideas over the Atlantic was the Swiss writer Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, now almost forgotten, but at one time a best-selling author." For example, his understanding of checks and balances was much more sophisticated and practical than that of Montesquieu, in part because Burlamaqui's theory contained the seed of judicial review. He was frequently quoted or paraphrased, only sometimes attributed, in political sermons during the pre-revolutionary era. He was the first philosopher to articulate the quest for happiness as a natural right, a principle that Thomas Jefferson later restated in the Declaration of Independence.

Burlamaqui's description of European countries as forming "a kind of republic the members of which, independent but bound by common interest, come together to maintain order and liberty" is quoted by Michel Foucault in his 1978 lectures at the Collège de France in the context of a discussion of diplomacy and the law of nations.

-- Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, by Wikipedia

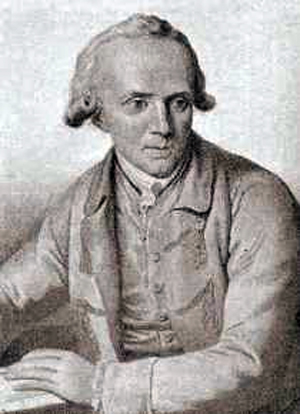

Albrecht von Haller,...

Albrecht von Haller (also known as Albertus de Haller; 16 October 1708 – 12 December 1777) was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, naturalist, encyclopedist, bibliographer and poet. A pupil of Herman Boerhaave, he is often referred to as "the father of modern physiology."

Haller was born into an old Swiss family at Bern. Prevented by long-continued ill-health from taking part in boyish sports, he had more opportunity for the development of his precocious mind. At the age of four, it is said, he used to read and expound the Bible to his father's servants; before he was ten he had sketched a Biblical Aramaic grammar, prepared a Greek and a Hebrew vocabulary, compiled a collection of two thousand biographies of famous men and women on the model of the great works of Bayle and Moréri, and written in Latin verse a satire on his tutor, who had warned him against a too great excursiveness. When still hardly fifteen he was already the author of numerous metrical translations from Ovid, Horace and Virgil, as well as of original lyrics, dramas, and an epic of four thousand lines on the origin of the Swiss confederations, writings which he is said on one occasion to have rescued from a fire at the risk of his life, only, however, to burn them a little later (1729) with his own hand.

Haller's attention had been directed to the profession of medicine while he was residing in the house of a physician at Biel after his father's death in 1721. While still a sickly and excessively shy youth, he went in his sixteenth year to the University of Tübingen (December 1723), where he studied under Elias Rudolph Camerarius Jr. and Johann Duvernoy. Dissatisfied with his progress, he in 1725 exchanged Tübingen for Leiden, where Boerhaave was in the zenith of his fame, and where Albinus had already begun to lecture in anatomy. At that university he graduated in May 1727, undertaking successfully in his thesis to prove that the so-called salivary duct, claimed as a recent discovery by Georg Daniel Coschwitz (1679–1729), was nothing more than a blood-vessel. In 1752, at the University of Göttingen, Haller published his thesis (De partibus corporis humani sensibilibus et irritabilibus) discussing the distinction between "sensibility" and "irritability" in organs, suggesting that nerves were "sensible" because of a person's ability to perceive contact while muscles were "irritable" because the fiber could measurably shorten on its own, regardless of a person's perception, when excited by a foreign body. Later in 1757, he conducted a famous series of experiments to distinguish between nerve impulses and muscular contractions...

[ I]n 1728 he proceeded to Basel, where he devoted himself to the study of higher mathematics under John Bernoulli. It was during his stay there also that his interest in botany was awakened; and, in the course of a tour (July/August, 1728), through Savoy, Baden and several of the cantons of Switzerland, he began a collection of plants which was afterwards the basis of his great work on the flora of Switzerland. From a literary point of view the main result of this, the first of his many journeys through the Alps, was his poem entitled Die Alpen, which was finished in March 1729, and appeared in the first edition (1732) of his Gedichte. This poem of 490 hexameters is historically important as one of the earliest signs of the awakening appreciation of the mountains, though it is chiefly designed to contrast the simple and idyllic life of the inhabitants of the Alps with the corrupt and decadent existence of the dwellers in the plains.

In 1729 he returned to Bern and began to practice as a physician; his best energies, however, were devoted to the botanical and anatomical researches which rapidly gave him a European reputation, and procured for him from George II in 1736 a call to the chair of medicine, anatomy, botany and surgery in the newly founded University of Göttingen. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1743, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1747, and was ennobled in 1749...

[H]e conducted a monthly journal (the Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen), to which he is said to have contributed twelve thousand articles relating to almost every branch of human knowledge. He also warmly interested himself in most of the religious questions, both ephemeral and permanent, of his day...

[H]e also found time to write the three philosophical romances Usong (1771), Alfred (1773) and Fabius and Cato (1774), in which his views as to the respective merits of despotism, of limited monarchy and of aristocratic republican government are fully set forth.

In about 1773, his poor health forced him to withdraw from public business. He supported his failing strength by means of opium, on the use of which he communicated a paper to the Proceedings of the Göttingen Royal Society in 1776; the excessive use of the drug is believed, however, to have hastened his death.

Haller, who had been three times married, left eight children...

In his Science of Logic, Hegel mentions Haller's description of eternity, called by Kant "terrifying" in the Critique of Pure Reason (A613/B641). According to Hegel, Haller realizes that a conception of eternity as infinite progress is "futile and empty". In a way, Hegel uses Haller's description of eternity as a foreshadowing of his own conception of the true infinite. Hegel claims that Haller is aware that: "only by giving up this empty, infinite progression can the genuine infinite itself become present to him."

-- Albrecht von Haller, by Wikipedia

Gabriel Seigneux de Correvon, Samuel-Auguste Tissot,...

Samuel Auguste André David Tissot (French: [tiso]; 20 March 1728 – 13 June 1797) was a notable 18th-century Swiss physician.

A well reputed Calvinist Protestant neurologist, physician, professor and Vatican adviser who practiced in the Swiss city of Lausanne. He wrote on the diseases of the poor, on masturbation, on the diseases of the men of letters and of rich people, and nervous diseases.

He devoted an 83-page chapter to the study of migraine in his Traité des nerfs et de leurs maladies (Treatise on the nerves and nervous disorders). He used his own observations and the existing medical treatises of the day...

In 1760, he published L'Onanisme, his own comprehensive medical treatise on the purported ill-effects of masturbation. Citing case studies of young male masturbators amongst his patients in Lausanne as basis for his reasoning, Tissot argued that semen was an "essential oil" and "stimulus" that, when lost from the body in great amounts, would cause "a perceptible reduction of strength, of memory and even of reason; blurred vision, all the nervous disorders, all types of gout and rheumatism, weakening of the organs of generation, blood in the urine, disturbance of the appetite, headaches and a great number of other disorders."

His treatise was presented as a scholarly, scientific work in a time when experimental physiology was practically nonexistent. The authority with which the work was subsequently treated — Tissot's arguments were even acknowledged and echoed by luminaries such as Kant and Voltaire — arguably turned the perception of masturbation in Western medicine over the next two centuries into that of a debilitating illness...

On 1 April 1787, Napoleon Bonaparte wrote to Dr. Tissot complimenting him for spending his “days in treating humanity” noting that his “reputation has reached even into the mountains of Corsica” and describing “the respect I have for your works…"

-- Samuel-Auguste Tissot, by Wikipedia

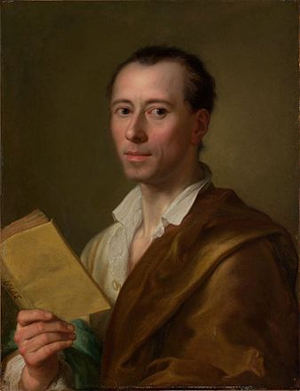

Johann Joachim Winckelmann ...

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (/ˈvɪŋkəlˌmɑːn/; German: [ˈvɪŋkl̩man]; 9 December 1717 – 8 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology", Winckelmann was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art. Many consider him the father of the discipline of art history. He was one of the first to separate Greek Art into periods, and time classifications. His would be the decisive influence on the rise of the Neoclassical movement during the late 18th century. His writings influenced not only a new science of archaeology and art history but Western painting, sculpture, literature and even philosophy. Winckelmann's History of Ancient Art (1764) was one of the first books written in German to become a classic of European literature. His subsequent influence on Lessing, Herder, Goethe, Hölderlin, Heine, Nietzsche, George, and Spengler has been provocatively called "the Tyranny of Greece over Germany."...

Winckelmann was homosexual, and open homoeroticism formed his writings on aesthetics. This was recognized by his contemporaries, such as Goethe...

With the intention of becoming a physician, in 1740 Winckelmann attended medical classes at Jena. He also taught languages. From 1743 to 1748, he was the deputy headmaster of the gymnasium of Seehausen in the Altmark but Winckelmann felt that work with children was not his true calling. Moreover, his means were insufficient: his salary was so low that he had to rely on his students' parents for free meals. He was thus obliged to accept a tutorship near Magdeburg. While tutor for the powerful Lamprecht family, he fell into unrequited love with the handsome Lamprecht son. This was one of a series of such loves throughout his life. His enthusiasm for the male form excited Winckelmann's budding admiration of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture.

In 1748, Winckelmann wrote to Count Heinrich von Bünau: "[L]ittle value is set on Greek literature, to which I have devoted myself so far as I could penetrate, when good books are so scarce and expensive". In the same year, Winckelmann was appointed secretary of von Bünau's library at Nöthnitz, near Dresden. The library contained some 40,000 volumes. Winckelmann had read Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Xenophon, and Plato, but he found at Nöthnitz the works of such famous Enlightenment writers as Voltaire and Montesquieu. To leave behind the spartan atmosphere of Prussia came as a great relief for him. Winckelmann's major duty involved assisting von Bünau in writing a book on the Holy Roman Empire and helping collect material for it. During this period he made several visits to the collection of antiquities at Dresden, but his description of its best paintings remained unfinished. The treasures there, nevertheless, awakened in Winckelmann an intense interest in art, which was deepened by his association with various artists, particularly the painter Adam Friedrich Oeser (1717–1799)—Goethe's future friend and influence—who encouraged Winckelmann in his aesthetic studies. (Winckelmann subsequently exercised a powerful influence over Johann Wolfgang von Goethe).

In 1755, Winckelmann published his Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst ("Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture"), followed by a feigned attack on the work and a defense of its principles, ostensibly by an impartial critic. The Gedanken contains the first statement of the doctrines he afterwards developed, the ideal of "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" (edle Einfalt und stille Größe) and the definitive assertion, "[t]he one way for us to become great, perhaps inimitable, is by imitating the ancients". The work won warm admiration not only for the ideas it contained, but for its literary style. It made Winckelmann famous, and was reprinted several times and soon translated into French. In England, Winckelmann's views stirred discussion in the 1760s and 1770s, although it was limited to artistic circles: Henry Fuseli's translation of Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks was published in 1765, and reprinted with corrections in 1767.

In 1751, the papal nuncio and Winckelmann's future employer, Alberico Archinto, visited Nöthnitz, and in 1754 Winckelmann joined the Roman Catholic Church. Goethe concluded that Winckelmann was a pagan, while Gerhard Gietmann contended that Winckelmann "died a devout and sincere Catholic"; either way, his conversion ultimately opened the doors of the papal library to him. On the strength of the Gedanken über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke, Augustus III, king of Poland and elector of Saxony, granted him a pension of 200 thalers, so that he could continue his studies in Rome.

Winckelmann arrived in Rome in November 1755. His first task there was to describe the statues in the Cortile del Belvedere—the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoön, the so-called Antinous, and the Belvedere Torso—which represented to him the "utmost perfection of ancient sculpture."

Originally, Winckelmann planned to stay in Italy only two years with the help of the grant from Dresden, but the outbreak of the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) changed his plans. He was named librarian to Cardinal Passionei, who was impressed by Winckelmann's beautiful Greek writing. Winckelmann also became librarian to Cardinal Archinto, and received much kindness from Cardinal Passionei. After their deaths, Winckelmann was hired as librarian in the house of Alessandro Cardinal Albani, who was forming his magnificent collection of antiquities in the villa at Porta Salaria.

With the aid of his new friend, the painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–79), with whom he first lived in Rome, Winckelmann devoted himself to the study of Roman antiquities and gradually acquired an unrivalled knowledge of ancient art....

Winckelmann's masterpiece, the Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums ("The History of Art in Antiquity"), published in 1764, was soon recognized as a permanent contribution to European literature. In this work, "Winckelmann's most significant and lasting achievement was to produce a thorough, comprehensive and lucid chronological account of all antique art—including that of the Egyptians and Etruscans." This was the first work to define in the art of a civilization an organic growth, maturity, and decline. Here, it included the revelatory tale told by a civilization's art and artifacts—these, if we look closely, tell us their own story of cultural factors, such as climate, freedom, and craft. Winckelmann sets forth both the history of Greek art and of Greece. He presents a glowing picture of the political, social, and intellectual conditions which he believed tended to foster creative activity in ancient Greece.

The fundamental idea of Winckelmann's artistic theories are that the goal of art is beauty, and that this goal can be attained only when individual and characteristic features are strictly subordinated to an artist's general scheme. The true artist, selecting from nature the phenomena suited to his purpose and combining them through the exercise of his imagination, creates an ideal type in which normal proportions are maintained, and particular parts, such as muscles and veins, are not permitted to break the harmony of the general outlines...

Winckelmann's writings are key to understanding the modern European discovery of ancient (sometimes idealized) Greece, neoclassicism, and the doctrine of art as imitation (Nachahmung). The mimetic character of art that imitates but does not simply copy, as Winckelmann restated it, is central to any interpretation of Enlightenment classical idealism.Winckelmann stands at an early stage of the transformation of taste in the late 18th century.

-- Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Wikipedia

and other Enlightenment authors.

The two magazine projects of the Typographic Society Bern aimed at an international exchange of knowledge. This allowed Tscharner and de Felice to create a correspondent network all over Europe.

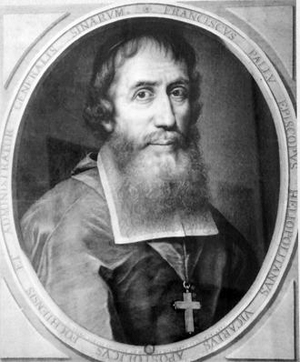

Portrait

An 18th-century depiction of de Félice is held by the Achenbach Foundation in the San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts. A Latin and 18th century French inscription by one of his sons, Carolus de Félice reads:

Original

Fortunatus De Felice

Roma 24 Augusti 1723. Natus: ibidem, deinceps.

Neapoli Phil. Phys. exp. et Mathem. quondam

Professor: Mundi, hominisque legum sedulus Inda-

gator, et felix qua Voce, qua Scriptus Interpres

Encyclopediae Ebrodunensis Contaborator et Editor

Cet Auteur, distingué par un profond Génie,

Dans le sein de l'Erreur trouva la Vérite;

Et sachant la montrer dans l'Encyclopédie,

S'est fait un titre sür à l'Immortalité.

Offerebat Obseq. et Devot. Filius

Carolus de Felice

Translation

Fortunato de Felice

Born: Rome, 24 August 1723

Naples – Philosophy, Physics and Maths

Professor – World, a zealous investigator

by this love of speech wrote

the Yverdon Encyclopaedia editor and contributor

This author, distinguished by a profound genius,

In the bosom of wandering found truth

And searching that in the encyclopedia

Immortalised himself

Offered dutifully by his devoted son, Carolus De Felice

[4]

He also had a portrait commissioned, done by an unknown artist. The current holder of the portrait, the de Felice Duchi Estate, puts this painting as the best representation of de Felice in existence.

Works

• Etrennes aux désœuvrés ou Lettre d'Quaker à ses frères et à un grand docteur. 1766th (In this work Felice railed against the so-called philosophers and Voltaire )

• Mémoires de la Société oeconomique de Berne (24 volumes, 1763–72)

• Essay manière la plus sûre d'un système de police établir of grains. Yverdon 1772nd

• Dictionnaire géographique, historique et politique de la Suisse. 2 vols. Neuchâtel 1775th

• Dictionnaire de justice naturelle et civile. 1778th 13 volumes

• Tableau philosophique de la religion Chrétienne, considérée dans son ensemble dans sa morale et dans ses consolations. Yverdon 1779th

• Eléments de la police générale d'un Etat. Yverdon 1781st

• Le développement de la raison . Oeuvres posthumous. Yverdon 1789th

• Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire universel raisonné of connaissances humaines. 42 volumes and 6 supplementary volumes. Yverdon 1770–1776. Reissue: Fischer Verlag, Erlangen 1993, ISBN 3-89131-069-2 . (38,000 pages on 257 microfiches.)

Further reading

• Full Biography and works of Fortunato De Felice

• De Felice Estate Website

Bibliography

• Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire universel raisonné des connoissances humaines (Yverdon, Switzerland. 42 volumes, 6 volumes Supplement, and 10 volumes of plates, 1770–1780), with the assistance of Leonhard Euler, Charles François Dupuis, Jérôme Lalande, Albrecht von Haller, et al.

• Mémoires de la Société oeconomique de Berne (24 volumes, 1763–72)

• Le Bacha de Bude (1765)

• De Newtonian Attractione, adversus Hambergen (1757)

• Quadro filosofico della religione cristiana (1757)

• Sul modo di formare la mente ed il cuore dei fanciuli (1763)

• Principii del diritto della natura a delle genti (1769)

• Lezioni di logica (1770)

• Elementi del governo interiore di uno stato (1781)[3]

References

1. Donato, Clorinda (1992). "The Letters of Fortunato Bartolomeo De Felice to Pietro Verri". MLN. 107 (1): 74–111. doi:10.2307/2904677. JSTOR 2904677.

2. http://www.cromohs.unifi.it/7_2002/donato.html Archived January 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Rewriting Heresy in the Encyclopedie d'Yverdon 1770–1780

3. http://www.alessandrodefelice.it/biogra ... Felice.doc

4. http://search3.famsf.org:8080/view.shtm ... cord=25735[permanent dead link]

http://art.famsf.org/anonymous/fortunat ... 9633021935 - Link to the print in the Achenbach Foundation

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. Missing or empty |title= (help)