Ezour-Védam: Europe’s illusory first glimpse of the Veda

by Dermot Killingley

This is a pre-publication version of an article published in Religions of South Asia Vol. 2, No. 1 (2008), pp. 23 43. The published version is available online from the publisher Equinox, http://www.equinoxpub.com

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

This article1 is about a Sanskrit text that no longer exists, and perhaps never did exist, except in a French version. It has been variously called a copy of the four Vedas (Voltaire, letter of 21 October 1760, Figueira 1993: 203; 224 n. 12), the most precious manuscript in the East (Voltaire Défense (1984)), an ancient brahmin book written long before Alexander the Great (Voltaire Mœurs (1963, 1: 62)), an abridgment of a commentary on the Veda (Voltaire Mœurs (1963, 1: 240)), a forgery (Ellis 1822), and a missionary tract (Sonnerat 1782). None of these descriptions is exact, though the last is the nearest to its true character, so far as we can ascertain it.

The most reliable research on this text has been done already by Ludo Rocher (1984), and before him by Francis Ellis (1822); I am very much indebted to both these. However, in this article study I propose to review the subject, to place it in its Indian and European contexts, and to bring out some points which were not clear to me from previous studies.

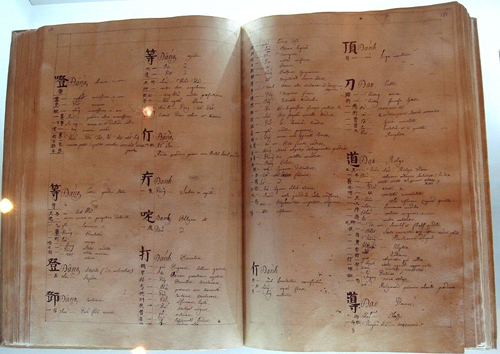

The Pondicherry collection of texts

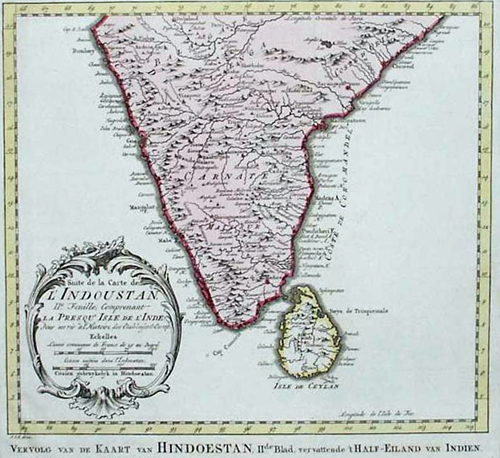

The book called Ezour-védam is one of a collection of manuscript dialogues which existed in the French Jesuit mission at Pondicherry, but are now lost (Rocher 1984: 74). Most of them were in Sanskrit and French versions on facing pages, though the Ezour-védam itself is only in French. They were composed in ślokas in Purānic style, but with faulty metre.2 It was not always possible to read the exact Sanskrit text, because they were in roman script in French spelling, influenced by Bengali pronunciation, and not always consistently or accurately written. The Bengali influence is clear from forms such as Chamo Bedo for Sāma-Veda, with o for the short vowel a, b for v, and ch (representing a ‘sh’ sound) for s.3 The other texts in the collection also have the word veda or beda in their titles (see below, p. 000), but none of them is what indologists would usually call a Vedic text.

The Ezour-Védam

The Ezour-Védam was the only part of this collection to circulate in Europe. The original title, in the Pondicherry collection, was Jozour Béd.4 This again reflects Bengali pronunciation, in which initial y is pronounced j , which in these manuscripts is often written z ; the pronunciation of j as z is common in North Indian languages. But the title Jozour Béd had been crossed out, and replaced in another hand with Ezour Védam. That is, the romanization based on Bengali pronunciation was replaced by one based on Tamil pronunciation.5 The title is thus a form of Yajur-Veda.6

However, the text has nothing to do with the Yajur-Veda. It is a dialogue between two speakers Vyāsa (romanized as Biach) and Sumantu (romanized as Chumantou or Chumontou).7 Vyāsa is the name of the legendary compiler of the Vedas, who was also the author of the Mahābhārata and Purānas. It is his role as author of the Purānas which is most relevant, since his contribution to the dialogue represents Purānic ideas. More specifically, it represents the Vaisnavism of the Bhāgavata Purāna and the Caitanya tradition, in which Krsna is not just an avatāra but the supreme God, and Vṛndāvan is his heaven (EV 151). Sumantu in the Mahābhārata is one of Vyāsa’s pupils.8

In the Ezour-Védam, Sumantu’s contributions to the dialogue are the longer and more interesting part. Vyāsa, as already mentioned, presents Purānic cosmology, mythology and ritual, saying that this is what he has taught people. Sumantu berates him for his ignorance and stupidity, and his sinfulness in deceiving others, and presents doctrines of his own which contradict Vyāsa’s. Vyāsa then confesses his error and becomes Sumantu’s pupil, reversing the roles in the Mahābhārata. This pattern is repeated throughout the Ezour-Védam. The form is thus similar to that of the dialogues in the Purānas, except that Vyāsa’s speeches are longer than those of a typical Purānic pupil, and he does far more than ask questions. Sometimes Sumantu asks questions about Vyāsa’s doctrines, just so that he can tell him how wrong they are. For instance, there is a long passage on the churning of the ocean of milk (EV 162-7), in which Sumantu repeatedly asks Vyāsa for more details, which he then ridicules.

Sumantu’s doctrines are sufficiently imbued with European thought to indicate a missionary source, although they are not entirely those of Catholic Christianity. God is almighty, invisible, infinite and merciful. A plurality of gods is denied (EV 161), there is only one God, and the supposed gods are only human. The soul is immortal, and the souls of the virtuous are rewarded with everlasting bliss (EV 159-60). There is no rebirth, and there is a firm line dividing humankind from animals: plants and animals are created to serve humankind, and only human beings are capable of sin (EV 149-50). Accordingly, the suffering of animals is not the fruit of sin but is a necessary consequence of their subservience to humankind (EV 50). The three gunas are taught with reference to their role in human character, but they are not inherent but accidental (in the philosophical sense of not being part of the essence), and one guṇa can be eliminated by cultivating another (EV 148-9). This amounts to an insistence on freewill.

There is a suggestion of the Fall, and of original sin, since the first people lived virtuously and blissfully (EV 114). ‘The first sin, once committed, led to many others’ (EV 115). But this does not mean that the tendency to sin is inherited by birth; it comes from association with evil people, and virtue can similarly be cultivated by associating with the good (EV 115). Sin is an offence against God, and only God can forgive it; this is urged against Vyāsa’s account of expiations (EV 157 8). Suicide – for instance by expiatory fasting – is the worst of crimes (EV 158).

One example which differentiates Sumantu’s doctrines from Christianity is that in rejecting avatāras he repeatedly denies that God can ever be incarnate. God creates and destroys by an act of will; it is therefore absurd that he should need a physical body to defeat any enemy (EV 153, 159). As was pointed out already by Ellis in 1817 (Ellis 1822: 35n.; see p. 000 below), this would make it difficult to introduce the Christian doctrine of the incarnation. Sumantu also denies the resurrection of the body. While the soul is immortal, the body decays, so there is no possibility of an incorruptible body (EV 159 60).

Vyāsa’s teachings contain some specifically Hindu9 ideas, but there are some interesting departures from their usual form. The guṇas, as mentioned already, are not innate in a person. The four yugas are mentioned, but each is followed by a deluge and a new creation (EV 132). The advantage of the Kali Yuga, which in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa (11, 5, 36; cf. Viṣṇu Purāṇa 6, 2) is that merit can be obtained by merely praising Kṛṣṇa, is that anyone can perform religious functions and learn the Veda regardless of caste (EV 171). The birth of Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva is related, but they are all three born from the original man. Brahmā is born from his navel – not from Viṣṇu’s; Viṣṇu is born from his right side and Śiva from his left (EV 113).10 These departures, particularly the one concerning the guṇas, which as suggested above protects the notion of freewill, seem to be modifications in the direction of European ideas.

Although its literary form places it in a traditional Hindu cultural context, the Ezour-védam contains indications that it was written by and for people to whom this context is foreign [Europeans!]. In an account of the measurement of time, which largely but not entirely follows the one in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, after a statement that 15 laghus (‘Logou’) make an hour (‘une heure’, but in the BhP the word is nārikā), we find an explanatory remark that the Indian hour contains only 24 minutes, before the series continues with the statement that two hours make a muhūrta (‘Muhurto’, EV 131). Later in the same account, it is explained that eight prahāras (‘prohor’) make ‘our 24 hours’. Though the hour (Skt. horā) is used in Sanskrit astronomical works, it is not part of the system presented in the Purāṇas and related texts. It is possible that these two references to the system of hours familiar in Europe were added as glosses at some stage in the transmission of the text. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that the eighteenth-century advocates and opponents of the antiquity of the Ezour-védam did not notice this clear indication that the text as it stands occupies a liminal position between two cultures.

Natural religion, Jesuits and non-Christian traditions

We cannot describe this document as teaching Christianity. We can, however, see it as a presentation of natural religion, as envisaged by many in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including Catholic theologians (Lagrée 1991). It was commonly held, though sometimes disputed, that every nation had some idea of a single, almighty, formless God, a common core of morality, and, according to some, an immortal soul which is rewarded and punished after death. Natural religion was believed to result from general revelation (as opposed to the special revelation of the Bible and the Church), or from the human mind and the evidence of nature. Polytheism and idolatry resulted from historical causes, summed up as corruption or perversion.

Natural religion included natural law, the scriptural basis for which is Romans 2.14, where St. Paul speaks of Gentiles who act according to the law although they do not have the law as the Jews do. The Ten Commandments (Exodus 20.2 17), with the exception of the fourth which refers to the culturally specific institution of the Sabbath, were sometimes taken as a summary of natural law, and we find the first five of them, with the same exception, in the Ezour-Védam. Vyāsa asks Sumantu what kinds of sins one can commit, and Sumantu’s answer consists mainly of neglect of the worship of God (the first commandment). The greatest sin of all is to give any being or thing the worship due to God (the second commandment, against idolatry, and also the first, against other gods). To use the name of God as an easy way to gain his mercy is a sin which God rarely forgives (the third, against taking the name of God in vain).11 Next to God, we should honour our father and mother (the fifth) (EV 155).

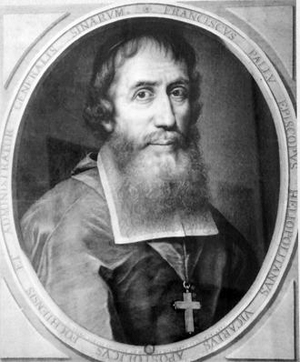

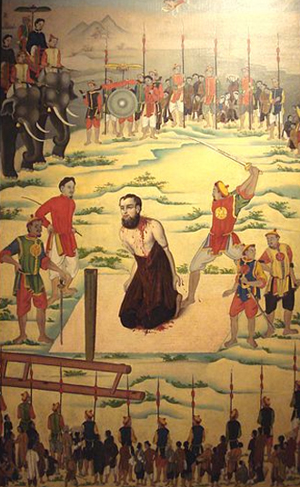

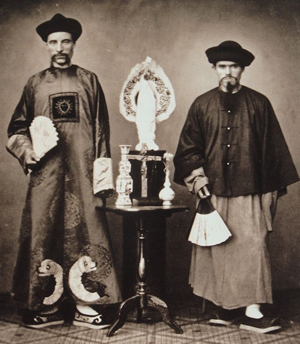

Natural religion was important for the missionary strategy of the Jesuits. Their readiness to find evidence of natural religion in non-European cultures inspired both their literary contribution to these cultures and their work in bringing knowledge of them to Europe. Besides Roberto di Nobili (1577-1656) and Constantine Joseph Beschi in South India and their contributions to Tamil literature, the English Jesuit Thomas Stephens (1549-1619) in western India wrote a Khrista purāna in Konkani in 1616.12 Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) engaged similarly with the Chinese tradition, not merely learning the language—in itself a great achievement—but operating within the literary tradition, using Confucian concepts, though he rejected those of Buddhism and Daoism. His Tiānzhŭ shíyì (‘true doctrine of God’) was ‘a treatise in natural theology ... a preparatory step towards the faith, not an epitome of the faith’ (Witek 1982: 147); his Jiāoyóu lùn (‘discourse on friendship’) and Érshíwŭ yán (‘twenty-five statements’) inaugurated ‘a type of moralising literature in which specifically Christian themes are absent or no more than marginal, and which therefore could easily appeal to Confucian literati’ (Zürcher 1996: 332).

Other Jesuits were able to operate within non-literate cultures, even those which others regarded as spiritual and intellectual vacuums. Francisco Pinto (1552-1608) was a missionary to the Tupí of Brazil, who were cited as a counter-example against the claim that all peoples had some form of religion (Lagrée 1991: 31; cf. Castelnau-l’Estoile 2006: 616). He became sufficiently acquainted with Tupí culture to be accepted by them as a shaman and rain-maker, and justified his method by telling his superiors that ‘Indians had to be taken to God slowly and progressively. First, they should be seduced and attracted by means of indigenous practices, which could be given a Christian meaning later’ (Castelnau-l’Estoile 2006: 622). Such dealing with non-Christian cultures was controversial, but was accepted by some as praeparatio evangelica—a preparation for the gospel. It was a speciality of the Jesuits, whose founder Ignatius Loyola held that ‘God could be found in all things — even, indirectly, in pagan customs’ (Castelnau-l’Estoile 2006: 623).

The Ezour-Védam is an example of this approach. It is not a Christian siddhānta, but a refutation of a series of Vaisnava pūrvapakṣas. A missionary faced with the difficulty of evangelizing high-caste Hindus may have decided that the difficulty arose from their following a polytheistic and idolatrous perversion of natural religion, and that to restore natural religion would make them receptive to Christian ideas. It was a commonplace of the French philosophes that a primitive Indian monotheism had been corrupted in the course of history by idolatry and superstition (Weinberger-Thomas 1983: 193-4). There are indeed places where Sumantu provides escape clauses which hint that his doctrines are not final. In his account of the yugas, he says that this is what they say about the duration of the yugas, but it is all pure fiction (EV 132). After describing svarga (‘heaven’) with its palaces, jewels, trees, rivers and apsarases, he adds: ‘That is what they say, but I don’t vouch for its truth’ (EV 129).13

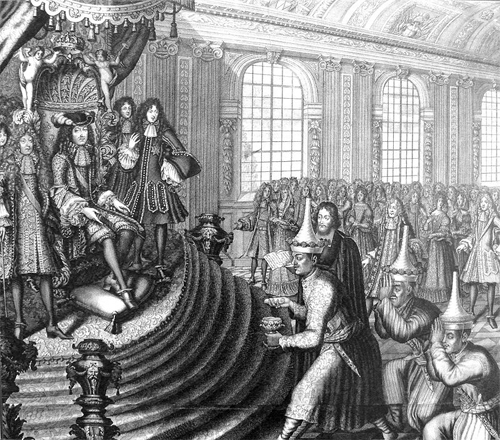

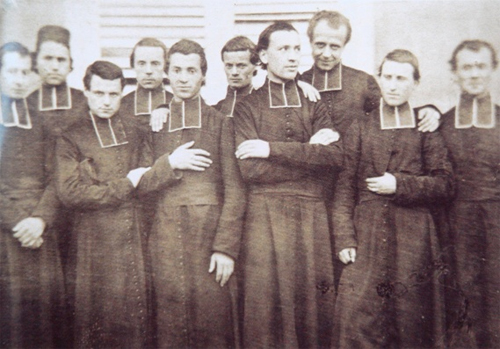

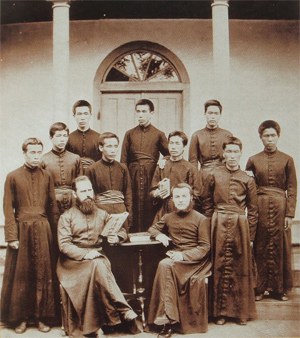

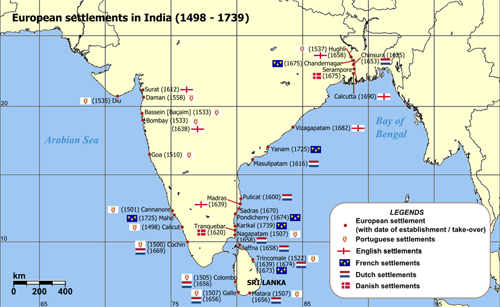

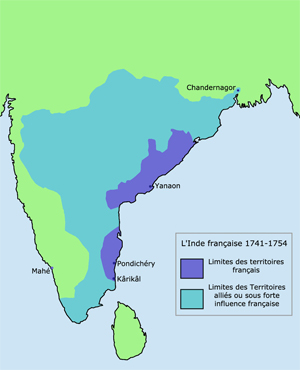

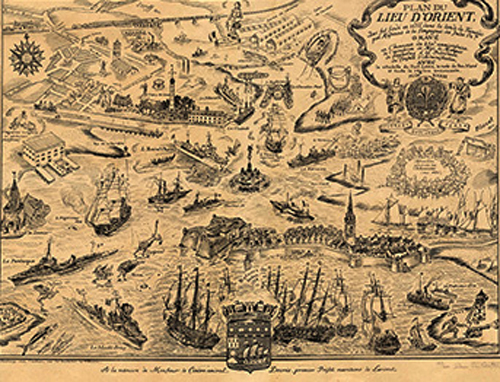

The Jesuits in South India had fled to Pondicherry from Siam (Thailand) in the late 17th century, and were supported by King Louis XIV and Louis XV and by the Compagnie des Indes. They followed the principles introduced by Roberto di Nobili (1577 1656), who gained the respect of brahmins by learning their traditions and following their rules of purity. This notable instance of the Jesuit method of operating within a culture, had been controversial from the outset, and in the eighteenth century it led to what was called the Malabar rites controversy. ‘Malabar’ meant Tamil, and the Malabar rites were forms of Catholic liturgy adapted to Tamil brahmin culture: an example of what is known to later missionary strategists and theorists as inculturation. The Jesuit missionaries considered that the Tamil features of these adaptations belonged to culture and not to religion, and were therefore compatible with Christianity; others in the church disagreed. After a series of setbacks in the 1730s, the Jesuit missionaries were defeated in this controversy by a Papal bull of 1744. Converts who had been attracted by the Malabar rites defected; and since the supply of texts depended on such converts, none were sent to Paris after 1735.

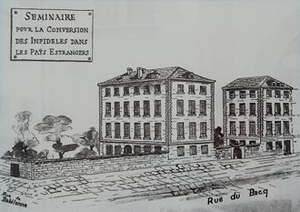

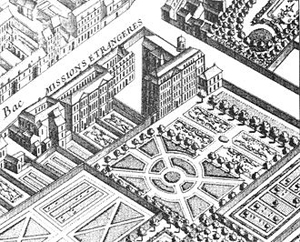

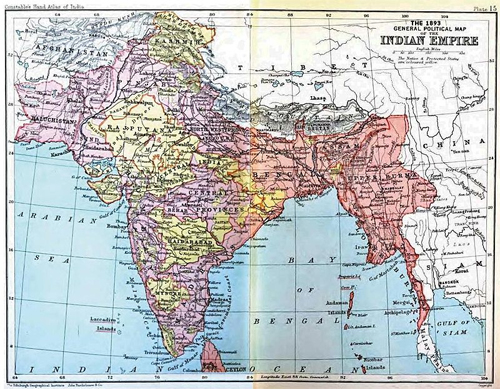

The same group of Jesuits had brought knowledge of the brahmin tradition to France through the Lettres Édifiantes, a series of missionary reports from different parts of the world which were published from 1702 to 1758. Intended to gain respect for the Jesuits in their controversies with Jansenists, Protestants and freethinkers, and to raise funds, these reports were an important source of knowledge of India in France, and thence in Europe. However, the Jesuit order was suppressed in France in 1761 4, and was abolished by the Pope in 1773. Henceforth the missionaries in India, referred to as the former Jesuits, belonged to the Société des Missions Étrangères. At the same time, French power was declining in India as British power expanded.

Eighteenth-century France, the Veda, the Ezour-Védam and Voltaire

The Veda was known by name in Europe since Abraham Roger’s book on the brahmins of South-Western India (first published in Dutch in 1651, translated into German in 1667 and into French in 1670). His description of it as a book of law containing all the beliefs and ceremonies of the brahmins remained standard at least to the end of the eighteenth century (Weinberger-Thomas 1783: 217).

In October 1760 a copy of the Ezour-Védam reached the hands of Voltaire,14 and for twenty years or more it was taken by him and some others as an example of ancient Indian wisdom. Other texts with better claims to be called Veda had come to Europe earlier. In the 1730s, the French Jesuits in Pondicherry in Tamil Nadu, and in Chandernagor in Bengal, had sent hundreds of Sanskrit manuscripts, obtained through the agency of Christian brahmins, 15 to the royal library (now the Bibliothèque Nationale) (Omont 1902; Filliozat 1954; Murr 1983: 235). In 1769 they sent a French translation, by Maridās Piḷḷai, of a Tamil version of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, which became an important source in France (e.g. Ste Croix 1778 vol. 2: 201).

Since the texts in the royal collection were in Sanskrit, they lay unread. The French text called Ezour-Védam which reached Voltaire had been brought to France by Louis Laurent de Féderbe, Comte de Modave or Maudave (1725-77),16 one of several French soldiers of fortune in India who were a source of knowledge in addition to the Jesuits (Lafont 2000: 24). He had served various Indian states from 1773, and died at Masulipatam (Machilipatnam, on the Andhra Pradesh coast north of the Krishna delta, at that time a French trading station) in 1777. It seems that he had obtained a copy of the Ezour-Védam without the knowledge of the former Jesuits, since Father Cœurdoux in 1771 thought the text was in the sole possession of Father Mozac in Chandernagor.17 Either Mozac had given Modave a copy unknown to Cœurdoux, or Modave had obtained it by fraud. Voltaire gave it to the royal library, after having a hasty and faulty copy made for his own use.18

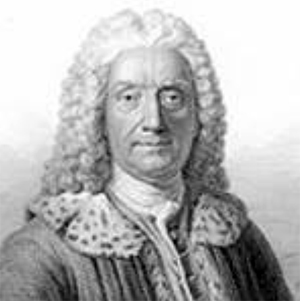

Voltaire’s interest in India was passionate but hardly thorough; he acquired fifty-eight books on the subject (listed Hawley 1974: 175-8)—surely a high proportion of those available in his time and place—but drew most of his material from only three of them: the Ezour-Védam, Holwell, and to a lesser extent Dow (Hawley 1974: 145-7; 174). However, his interest in India was subordinated to a higher aim: to break the monopoly of the Abrahamic traditions on the monotheistic ideas which Voltaire upheld, and to dispute the claims to divine favour both of the Catholic church and of the Jews. He was confident of having found in India a form of monotheism at once more ancient and morally purer than that of the Bible, and based on universal reason. For Voltaire, Christianity could only be a pale imitation and perversion of the wisdom of ancient India.

Voltaire, who had been educated by Jesuits, shared their enthusiasm for natural religion. His Essai sur les Mœurs is an attempt at universal history, designed to counter Bossuet’s Discours de l’histoire universelle (1681). While Bossuet (1627-1704) saw history as guided by divine providence, Voltaire saw it as under the sway of human activities such as commerce, politics and culture, including religion. In the field of religion the great nations are monotheistic, but in some nations natural religion has been corrupted by polytheism -– or by Catholicism. He gained some information from the Lettres édifiantes, though these assumed that influence had been in the opposite direction: India had learnt everything from the West (Hawley 1974: 142-3). The Ezour-Védam was for Voltaire his first and only opportunity to draw directly on Indian wisdom, and from 1761 onwards he used it enthusiastically, as confirmation of his views on the origins of civilization and of religion.

Voltaire refers to and quotes from the Ezour-Védam in the 1761 edition of his Essai sur les mœurs,19 his Additions à l’essay sur l’histoire générale (1763, a supplement to a work published in 1756), La philosophie de l’histoire par feu l’abbé Bazin (1765),20 Défense de mon oncle (1767), and, more briefly, in his Dictionnaire philosophique 1764). He does not seem quite sure of its status as a Veda; he calls it variously a commentary or an abridgment of a commentary, but also says it reports the words of the Vedam; in a letter of 21st October 1760 he calls it ‘a copy of the four Vedams’ (Figueira 1993: 203; 224 n. 12). He later explains the title as meaning ‘commentary on the Vedam’.21

While Voltaire is uncertain about the relation of the text to the Veda, he is sure that it predates Alexander the Great’s invasion of India, perhaps by four hundred years.22 He has two reasons for this dating. The first depends on the idea of a primitive Indian monotheism already mentioned (p.000). Sumantu, Voltaire argues, describes the uncorrupted monotheistic religion of ancient India, combatting the idolatry which was beginning to infect it. The ancient Greek sources show that Indian religion was already corrupted by idolatry, superstition and fables before Alexander, and this is corroborated by the history of religion in China, whither the corruption had spread from India; the text must therefore be considerably earlier. Voltaire’s second reason, which he says is equally strong, is that the place-names mentioned are Sanskrit ones,23 not those in the Greek sources. Thus we have Zomboudipo (Jambu-dvīpa) for India, Zanoubi (Jāhnavī) for Ganges, and Meru for the mountain which the Greeks knew as Immaos. ‘Not one of the names given by the Greeks to the lands they conquered is to be found in the Ezour-Védam’ (Voltaire, Défense (1984: 222)).

Both these reasons are not only feeble in the extreme, it is hard to see what Voltaire means by them. There is nothing in the Ezour-Védam to suggest that the beliefs and practices which Sumantu and Voltaire condemn are new. On the place names, it is not true that none of those known to the ancient Greeks is in the Ezour-Védam: Gaṅgā is named several times (EV 112; 120; 198), and identified with Zannobi (Jāhnavī) (EV 120). Indeed, unless Voltaire had read this identification he would have no reason to say that the Ganges is called Zanoubi; while his mistaken identification of Meru with Immaos or Himalaya is quite groundless. Even if it were true that the names known to the Greeks did not appear in the text, that would tell us nothing about its date, unless we were to suppose that Alexander somehow successfully banned the use of any other names. Voltaire’s proofs show only that he is a master of the non sequitur, and that he has not thoroughly read the book he admires so much.24 As Filliozat remarked (1954: 278), Voltaire treated available knowledge as a ragbag (fatras) from which he could pick what he needed for his arguments, with no way of telling which of his contemporaries were real scholars. Sceptics can be incredibly credulous.

The Ezour-Védam after Voltaire

While Voltaire was repeatedly citing the Ezour-védam from his own hastily made copy, another, containing additional material, was obtained from Pondicherry by Tessier de la Tour, nephew of M. Barthélemy, an official at Pondicherry who had also been the source of the copy brought by Modave to Voltaire. This document reached the hands of Anquetil Duperron, who had learnt of its existence in 1766 (Rocher 1984: 8). Anquetil quotes from it in his preface to the Avesta (Anquetil 1771, 1: lxxxiii-lxxxvii),25 and became ‘the staunchest champion of the authenticity of the EzV’ (Rocher 1984: 15). A third copy, also in the Bibliothèque Nationale, was in a private French collection at least as early as 1755 (Rocher 1984: 85 86). All three of these copies are in French; no Sanskrit original has been found. The French text was printed in 1778 at Yverdon, Switzerland, from Voltaire’s copy supplemented by Anquetil’s, with a long introduction and notes which are anonymous, but known to be by Guillaume de Clermont Lodève, baron de Ste Croix (1746-1809) (Hawley 1974: 173; Rocher 1984: 10). By rejecting Voltaire’s claims for the antiquity of the Ezour-Védam, by introducing French readers to Halhed’s Code of Gentoo Laws (published in 1776), and by criticizing Holwell and Dow, Ste Croix considerably advances the knowledge of ancient India available in French. A German translation of the Yverdon version soon followed (Ith n.d.).26

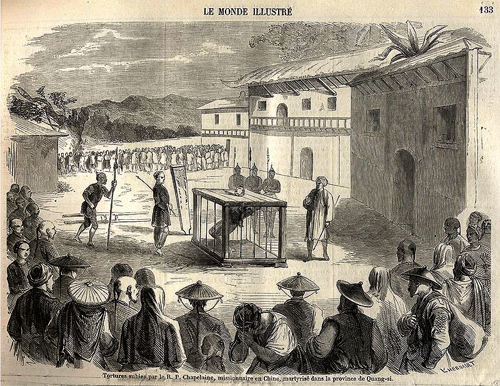

The first serious challenge to the genuineness of the Ezour-Védam came from Pierre Sonnerat, who posited a Christian origin. Sonnerat had travelled in the Indian Ocean and as far as the Philippines from 1768 to 1774, and on his return was sent to explore India. The outcome was his Voyages aux Indes orientales et à la Chine, fait par ordre du roi depuis 1774 jusqu’en 1781, published in two volumes in Paris in 1782: a book which goes beyond the bounds of a travel book, and beyond the natural history which was his main subject, into an enquiry on the cultural and physical history of humankind, in the philosophe tradition; it also contains much that is second-hand, taken from unacknowledged sources (Weinberger-Thomas 1983: 178-182). There, he describes the Ezour-Védam as a book of controversy written at Masulipatam by a missionary. Why he should locate the author there is not clear, but the inference that he was a missionary is reasonable. The Austrian Carmelite missionary Paulinus a Sancto Bartholomaeo (1749 1806) also rejected it. Ste Croix continued to believe it a genuine Indian document, though not as ancient as Voltaire claimed. Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838), a pioneer of Arabic and Persian studies, also accepted it, pointing out that ‘whatever the learned missionary [Paulinus] may say, this book, which is directed against the idolatrous cult of the Indians, would be a very strange catechism of the Christian religion’ (Rocher 1984: 15). Anquetil mentions it again as a source for Indian philosophy in his preface to his translation of the Upaniṣads published in 1801 2, where he accuses Sonnerat and Paulinus of ignorance of India. The question was becoming a point of conflict between textual scholars and observers in the field.

Francis Ellis’ research

The text was difficult to assess because it was neither Hindu nor Christian, and indeed neither exclusively Indian nor exclusively European. The distinctive Europeanness of some of its ideas would not be apparent to believers in natural religion, and it was hard to test its claim to be a Veda, when before Colebrooke’s survey of 1802 there was little knowledge of what a Veda or the Veda was. The person who did the most to settle the matter was Francis Whyte Ellis (1777 1819), who like Colebrooke was an official of the East India Company doing research in his spare time. The Ezour-Védam, like India itself, passed from the French-speaking to the English-speaking world.

In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a [French] Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão… Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the samhitas of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century…

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, [which] are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

It is perhaps significant that it was in a royal library, rather than in a Brahmin pathasala, that Polier found manuscripts of the Vedas. But the same is not true of the manuscripts acquired in Banaras only fifteen years later by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, during the period (1795–97) when he was appointed as judge and magistrate at nearby Mirzapur…I cannot conceive how it came to be ever asserted that the Brahmins were ever averse to instruct strangers; several gentlemen who have studied the language find, as I do, the greatest readiness in them to give us access to all their sciences. They do not even conceal from us the most sacred texts of their Vedas.

The several gentlemen would likely have included General Claude Martin, Sir William Jones, and Sir Robert Chambers. These were all East India Company employees who obtained Vedic manuscripts (Jones from Polier) in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Why was it so much easier for Polier, Colebrooke, and others to obtain what it had been so difficult for the Jesuits and impossible for the Pietists?...

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

The two greatest empires were the British and the French; allies and partners in some things, in others they were hostile rivals. In the Orient, from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to Indochina and Malaya, their colonial possessions and imperial spheres of influence were adjacent, frequently overlapped, often were fought over. But it was in the Near Orient, the lands of the Arab Near East, where Islam was supposed to define teal and racial characteristics, that the British and the French countered each other and “the Orient” with the greatest intensity, familiarity, and complexity. For much of the nineteenth century, as Lord Salisbury put it in 1881, their common view of the Orient was intricately problematic: “When you have got a ...faithful ally who is bent on meddling in a country in which you are deeply interested -- you have three courses open to you. You may renounce -- or monopolize -- or share. Renouncing would have been to place the French across our road to India. Monopolizing would have been very near the risk of war. So we resolved to share.”10

And share they did, in ways that we shall investigate presently. What they shared, however, was not only land or profit or rule; it the kind of intellectual power I have been calling Orientalism. In a sense Orientalism was a library or archive of information commonly and, in some of its aspects, unanimously held. What bound the archive together was a family of ideas11 and a unifying set of values proven in various ways to be effective. These ideas explained the behavior of Orientals; they supplied Orientals with a mentality, a genealogy, an atmosphere; most important, they allowed Europeans to deal with and even to see Orientals as a phenomenon possessing regular characteristics.

-- Orientalism, by Edward W. Said

Ellis was employed in the East India Company’s base at Fort St. George (Madras / Chennai). His greatest scholarly achievement was to show the existence of a Dravidian family of languages, distinct from the Indo-Aryan family -– an idea that is taken for granted now, but which was not widely accepted until it was developed further by Robert Caldwell some forty years later. Ellis presented it in an introduction to someone else’s book, a grammar of Telugu written by A. D. Campbell for the company’s trainees in the College of Fort St. George, the South Indian counterpart to the College of Fort William in Calcutta.

In 1816, Ellis visited the former Jesuit mission in Pondicherry, and examined a collection of eight books of manuscript, in romanized Sanskrit reflecting Bengali pronunciation and French spelling, with a French version on the facing page. Some of the books contained more than one text, some contained part of one and part of another, and one contained a fair copy of the contents of some of the others. Some of the paper had a watermark with the date 1742. Some passages lacked the translation, while one, which is the Ezour-Védam, had the French but no Sanskrit. From the samples given by Ellis, we find that the Sanskrit is in ślokas, often irregular, and the French version is abridged -– or else, if the French was the original, the Sanskrit was expanded. The titles all contain the word Veda, e.g. Zozochi kormo bédo (apparently yajuṣ-karma veda), Zosur Beder Chakha27 (yajur-vedasya śākhā), La chaka du Rik et de28 Ezour védam (ṛg-veda śākhā, yajur-veda śākhā) Chama Védan (sāma-veda), Odorbo Bedo Chakha (atharva-veda-śākhā). One text, Rik Opo Bédo (perhaps ṛg-upaveda) has the title also in Tamil script reflecting Tamil pronunciation, irukku-vedam (ṛg-veda). He describes them as ‘an instance of literary forgery, or rather, as the object of the author or authors, was certainly not literary distinction, of religious imposition without parallel’ (Ellis 1822: 1).

Ellis’ description was read in a paper to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1817, and published in 1822. It is all the more important because, as mentioned already, the manuscripts are now lost (Rocher 1984: 74); Ellis’ article is the source of Rocher’s description as well as mine. They were last described at first hand by J. Castets, S.J., in a monograph published in Pondicherry in 1935; he says they have deteriorated since Ellis’ time, and even his description is mainly based on Ellis.

There are still many uncertainties about these texts:

Who wrote the Sanskrit ślokas, and why?

Why were the ślokas transcribed in an inconsistent and ambiguous romanization, instead of being preserved in an Indic script?

Who wrote the French version, and why?

Why are they called Vedas?

The first and second of the above questions do not apply to the Ezour-Védam, which has no Sanskrit version, but only to the other texts in the collection, which are now lost except for the samples published by Ellis. In the case of the Ezour-Védam, Rocher argues that there was no Sanskrit original; the text was written in French, by any one of a number of Jesuit missionaries, in order to be translated into Sanskrit.29 The author must have been someone familiar with European ideas, and with a knowledge of Purānic tradition, but probably a faulty knowledge, since there are so many oddities in Vyāsa’s accounts.30