by Aya Elamroussi

Contributors Claudia Dominguez

CNN

Published 24th August 2022

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- Noble lie [Pious Fiction] [Pious Fraud] [Pious Invention], by Wikipedia

-- Outline of forgery, by Wikipedia

-- Literary forgery, by Wikipedia

-- False document, by Wikipedia

-- Pseudepigrapha, by Wikipedia

-- Donation of Constantine, by Wikipedia

-- A treasured manuscript in a college library that was believed to have been written by Galileo is a forgery, university says, by Aya Elamroussi

-- The Artist Who Got Rich Forging Picasso & Matisse: Real Fake: Elmyr de Hory, by Perspective

-- Forgery, by Wikipedia

Among the heavenly bodies the ancients worshipped chiefly the sun not, thinks Herbert, 'in itself', but, like Plato, as the 'sensible simulachrum' of God.4 [Herbert, De Rel. Gent., p. 19: ' ... quamvis superius Sole numen sub hisce praesertim vocabulis coluerunt Hebraei, Solem, neque aliud numen, intellexerunt Gentiles, nisi fortasse in Sole, tanquam praeclaro Dei summi specimine, et sensibili ejus, ut Plato vocat, simulachro, Deum summum ab illis cultum fuisse censeas: quod non facile abnuerem, praesertim quum Symbolica fuerit omnis fere religio Veterum ...', (Google translate: ... although above the Sun the god under these particular terms The Hebrews worshiped the Sun, and no other god, the Gentiles understood, except perhaps in the Sun, as the glorious image of the supreme God, and his sensibility, as Plato calls in a pretense, you may think that God was the highest worship by them: which is not easy I would refuse, especially since almost all the religion of the Ancients was symbolic...') Plato, Republ., VI, 508 B-C.] This sunworship was then, in Herbert's terms, a cultus symbolicus [symbolic worship], not a cultus proprius [proper worship]; and throughout his treatise he insists that the pagan cult of natural objects, and of men, was of this symbolic nature, at least among educated people.5 [ ibid., pp. 183-4, 222.] 'That the cult of the sun was both very ancient and universal' is witnessed by all ancient historians; men received it 'from the very dictate of Nature'.6 [ibid., p. 20: 'Solis cultum tum antiquum maxime, tum universalem fuisse, testantur non solummodo S. S. sed Homerus, et Hesiodus, ipsi quoque veteres Historici ... Ad Coelos igitur, ex ipso Naturae dictamine, non maximis in periculis tantum, sed in rebus secundis, oculos supplicesque manus tendebant ...' (Google translate: The ancient worship of the sun especially, and that it was universal not only St. S., but Homer and Hesiod, themselves ancients, testify Historians ... To the Heavens therefore, from the dictates of Nature itself, not in the greatest perils so much, but in secondary matters, they stretched out their eyes and their supplicating hands.)] Herbert then proceeds to demonstrate, with a considerable show of erudition, that the names of most of the pagan gods originally referred to the sun, and that the Hebrew names for God were taken by the Gentiles to mean the sun, so that we have a series of equations, such as Jehovah = Iacchus or Bacchus = sun, or Adonai = Adonis = sun.1 [ibid., pp. 16-9, 20-31.] An Orphic hymn is quoted to show that Priapus was one of the names given to the sun;2 [ibid., p. 25; Orphei Hymni, ed. G. Quandt, Berolini, 1955, p. 7 ([x], 1. 8-9).] and a chapter is devoted to showing that the names of the planets originally referred to the sun.3 [ibid. pp. 29-31.]

In spite of the primacy given to the sun, the other planets and stars were not neglected in the ancient religion; for Plato, in the Cratylus, says that the most ancient Greeks 'believed, like many present-day barbarians, the only gods to be the sun and moon, earth, stars and sky', and, in the Timaeus and Laws, he states that the world, sky and stars are gods. Many other 'egregious philosophers', especially Stoics, were of this opinion.4 [ibid., pp. 39-40; Plato, Cratylus, 397 C- D, Timaeus, 39 E-40 C, Laws, 899 A-B.] Some modern philosophers believe the planets to be animated, and indeed 'the most approved Christian authors, among them Thomas Aquinas, consider that the stars are alive'. Herbert goes on:5 [ibid., p. 40: 'Et sane vivere astra, probatissimi Authores Christiani censent; et cum primis Thomas Aquinas, et alii, quorum catalogum in Vossio lib. 2 de Idol. videre est ... Verum enimvero si vivunt, coli posse aliquo cultu sacro et religioso, qualis hominibus sanctis convenit, doctissimus Jesuita in dissertatione sua de Caelo 4. putat: Majorem quippe honorem, et cultum supera, quam infera, aeterna quam caduca, mereri videntur, tum praesertim inter illos, qui post hanc vitam transactam, faelicitatem sempiternam in Caelo et Astris dari statuebant. Turpe et indecorum enim existimaverant, non advenerari ea, unde ortum ducere, et in quae redire animas suas (Deo summo ita volente) crederent antiquitus Philosophi Sacerdotesque Gentiles.' (Google translate: And of course the stars live, the most approved Christian authors consider; and with the first Thomas Aquinas, and others, whose catalog is in Vossio lib. 2 of Idol. it is to be seen ... It is indeed true that if they live, they can be worshiped with some sacred worship and religious, such as befits holy men, the most learned Jesuit in his dissertation 4. He thinks of his own from Heaven: For greater honor and worship is higher than hell, eternal rather than ephemeral, they seem to deserve, and especially among those who are after this they decided to give eternal happiness in heaven and the stars after the life was spent. For they had thought it shameful and unseemly not to arrive at the thing from which it arose to lead, and into which they would return their souls (so willing to the supreme God) of ancient times Gentile Philosophers and Priests.')]Verily indeed, if they are alive, they can be worshipped with some sacred and religious cult, such as is fittingly given to holy men; which is the opinion of a most learned Jesuit in his 4th dissertation on the heavens; since those things that are higher seem to deserve greater honour and worship than those that are lower, the eternal than the corruptible, especially among people who considered that, after this life is over, sempiternal felicity is enjoyed in the heavens and stars.

Among the planets Jupiter is particularly important, since under this name the ancients worshipped a pantheistic God, witness Orpheus' Hymn of Jove and the Stoics.1 [ibid., p. 47: 'Altius tamen quiddam quam Stellam hanc, nedum numen animale ex Iove, intellexerunt olim Philosophi. Ideo Orpheus Iovem omnium primum atque postremum appellabat, eumque omnia tempora, quae unquam fuere, praecessisse, permansurumque post cuncta quae futura sint; illum supremam mundi partem colere, infimam quoque omnium attingere, totumque ubique esse dixit.' (Google translate: 'However, there is something deeper than this Star, let alone an animal god from Jupiter, as the Philosophers once understood. Therefore, Orpheus Jupiter first of all and he called it the last, and that all the times that ever were had preceded him, and will continue after all things that are to come; that supreme of the world He said to worship a part, to reach also the lowest of all, and to be the whole everywhere.') cf. supra, p. 86.] Moreover, as a planet, Jupiter's influence was believed to be especially benign, being intermediate between 'the fervour of Mars and the frigidity of Saturn'; and indeed, so efficacious was its influence, that in certain conjunctions it enabled men to obtain everything they prayed for -- 'of which Peter of Abano writes that he has found it to be most true'.2 [ibid., pp. 46- 8: 'Quum enim id temperamenti huic Stellae misti crederetur, ut medium quid inter Martis fervorem Saturnique frigiditatem obtineret, benigna prorsus Stella habebatur ... non solummodo salutaris ad omnia existimatus fuit Planeta hiC, sed ita efficax, ut si Luna ilLi jungeretur cum Capite Draconis omnia impetrari possent, quae a Deo postulantur; quod et Petrus Aponensis scribit se comperisse verissimum'; Petrus Aponensis, Liber Conciliator, Venetiis, 1521, Diff. 113, 156, fos 158 vo, 202 ro. (Google translate: For when it was believed that the temperament of this star was mixed, so as to obtain a medium between the heat of Mars and the coldness of Saturn, kind He was regarded as a total star ... not only was he considered a savior for all things This planet, but so efficacious, as if the Moon there were united with the Dragon's Head they could obtain what is required of God; which also Peter of Aponensis writes himself to have discovered the truest thing'; Peter Aponensis, Liber Conciliator, Venice, 1521, Diff. 113, 156, fos 158 vo, 202 ro.)] Immediately after this casual reference to dangerous mediaeval magic, Herbert, passing to Saturn, mentions Galilei's Medicean satellites3 [ibid., p. 48.] (he had already for Mars referred us to Kepler and Scheiner),4 [ ibid., p. 46.] and then discusses the poetic fables about Saturn. Some of these do conceal a solid truth, such as that of Saturn being bound by Jove, which means that the 'malignant power of Saturn may be corrected by the salutary star Jupiter'. Saturn, according to the Platonists, produces contemplative characters and melancholics; and according to 'our Roger Bacon', the Jews chose Saturday as the Sabbath, because Saturn, being 'idle and slow, is not fortunate or suitable for doing things'. Finally, to wind up the chapter on planets, we are told, for 'the harmonious proportion of the planets to consult, after Pythagoras, Kepler'.5 [ibid., p. 48: 'Ita ubi Saturnum a Iove in vincula conjectum, et in Tartara paecipitem datum, narrant Poetae, id ita intelligunt Mythologi, ut Saturni vis maligna a Iovis salutari sydere castigetur, et corrigatur, ingensque aeris altitudo, ubi primitus eorum operationes perficiantur, Tartarus hic sit. Saturnus quoque contemplationis author esse existimatur a Platonicis, tum quod Caelo supremo proximus, vim illam inderet animis, tum quod animas ita ad primordia sua revocet ... In anno quoque eum praefecere [sic] Autumno, in Hebdomade Diei Septimae, ut ideo noster Rogerus Bacon scribere non dubitaverit, Iudaeorum more tum temporis feriandum, quia segne et tardum sydus Saturni parum sit foelix, et idoneum rebus agendis . . . De harmonica Planetarum proportione consulatur post Pythagoram Keplerus.' (Google translate: Thus, when Saturn was thrown into chains by Jupiter, and into Tartarus the poets tell us that he was given a sword, and the mythologists understand it in this way, as the force of Saturn the wicked will be punished by Jupiter's salutary star, and he will be corrected, and the great height of the air, where at first their operations were accomplished, let Tartarus be here. Saturn too It is thought by the Platonists to be responsible for contemplation, as well as for the highest heaven next, he would impart that power to the souls, and that souls thus to their beginnings he will call back ... In the year also to preside over him [sic] in the Autumn, in the Week of the Day Seventh, as our Roger Bacon did not hesitate to write, of the Jews to be celebrated at the same time, because the slow and slow star of Saturn is small happy, and fit to do things. . . On the Harmonic Proportion of the Planets Kepler is consulted after Pythagoras.')]

-- The Ancient Theology: Studies in Christian Platonism from the Fifteenth to the Eighteen Century, by Daniel Pickering Walker (1914-1985)

[A]s I said before, since at that time no laws were yet administered, nor punishment suspended over evil deeds, they recorded as rightful and brave deeds, adulteries and sodomy, and incestuous and unlawful marriages, and bloodshed and parricides, and murders of children and brethren, and moreover, wars and seditions actually carried on by their own champions, whom they both accounted and called gods, and bequeathed the remembrance of them as worshipful and brave to later generations.

Such was the ancient theology which was transformed by certain moderns of yesterday's growth, who boasted of having a more reasonable philosophy, and introduced what they called the more physical view of the history of the gods, by devising more respectable and ingenious explanations for the legends: yet they neither escaped altogether the fault of their forefathers' impiety, nor, on the other hand, could endure the self-manifested wickedness of their so-called gods.

So, in their eagerness to palliate the fault of their fathers, they changed the legends into physical narratives and theories, and boasted, as the more mystical view, that the things which give nourishment and increase to the nature of the body are those which the legends set forth.

Going on from this point, these men also gave the title of gods to the elements of the world, not just merely to sun and moon and stars, but also to earth and water, and air and fire, and their combinations and resultants, and moreover to the seasonable fruits of the earth, and all other produce of food both dry and liquid: and these very things, regarded as causes of the life of the body, they called Demeter, and Kore, and Dionysus, and other like names, and, by making gods of them, introduced a forced and untrue embellishment of their legends.

But it was in a later age that these men, as if ashamed of the theologies of their forefathers, added respectable explanations, which each invented of himself, to the legends concerning their gods; for no one dared to disturb the customs of their ancestors, but paid great honour to antiquity, and to the familiar training which had grown with them from their boyhood.

Their elders, however, besides their deifications of men, gave equal rank to their consecrations of brute animals, because of the benefit derived from them also for the causes previously assigned; and they devoted equal religious worship to the brutes, and with libations, sacrifices, mystic rites, and hymns, and songs, exalted the honours paid to them, in the same manner as to the men who had been deified. And so they marched on to such a pitch of evil, that, through excess of unbridled lust, they consecrated with divine honours those parts of the body that lead to impurity, and the unrestrained passions of mankind, while their so-called theologians declared that in these things there is no need at all to use solemn phrases. We must, then, hold it to have been proved on the highest testimony, that the oldest generations knew nothing more at all than the history, but adhered to the legends only. Since, however, we have once begun to glance at the august and recondite doctrines of the noble philosophers, let us go on and examine these also more fully, that we may not seem to be ignorant of their wonderful physical theories.

But before we make our exposition of these doctrines, we must first indicate the mutual contradiction even here of these admirable philosophers themselves. For some of them make random statements, and set forth their opinions according to what comes into the mind of each individually: for they do not agree one with another even in their physical theories. While others more candidly sweep away the whole system, and banish from their own republic not only the indecent stories about the gods, but also the interpretations given of them; though sometimes they speak softly of the legends through fear of the punishment threatened by the laws.

Listen then to the Greeks themselves speaking by the mouth of the one noblest of them all, now banishing and now again adopting the legends. Thus their admirable Plato, when he lays bare his own preference, with great boldness forbids altogether the thinking or saying such things concerning the gods, as had been said by them of old, whether they contained anything latent indicated in allegorical meanings, or were spoken without any allegorical meaning at all. But at other times he speaks softly of the laws, and says that we ought to believe the legends about the gods, though there is nothing indicated by them in allegorical meanings.

But when at last he has dissociated his own theology from the ancient legends, and has stated his physical theories about the heaven, and sun, and moon, and stars, and moreover about the whole cosmos, and the parts of it severally, he again specially and separately goes through the ancient genealogical accounts of the gods just as follows word for word in the Timaeus....

Such, we see were the opinions entertained by the best philosophers, and by the ancient and most eminent men of the Roman empire concerning the theology of the Greeks----opinions which give no admission to physical theories in their legends concerning the gods, nor to their gorgeous and sophistical impostures...

Now much labour has been spent upon these subjects by numberless other professors of philosophy, who have made different subtle explanations of the same, and strongly insist that the opinion which occurred to each was the exact truth. But for my part I am content to bring forward my proofs from the most illustrious authors who are well known to all philosophers, and have carried off no small reputation for philosophy among the Greeks.

Of whom take first and read the words of Plutarch of Chaeroneia on the questions before us, wherein with solemn phrase he perverts the fables into what he asserts to be mysterious theologies....

But why need I thus anticipate, when we may hear the man himself, in the essay which he wrote On the Daedala at Plataea, expounding as follows what was hidden from the multitude in the secret physiological doctrines concerning the gods.

[PLUTARCH] 'THE physiology of the ancients both among Greeks and Barbarians was a physical doctrine concealed in legends, for the most part a secret and mysterious theology conveyed in enigmas and allegories, containing statements that were clearer to the multitude than the silent omissions, and its silent omissions more liable to suspicion than the open statements. This is evident in the Orphic poems, and in the Egyptian and Phrygian stories: 'out the mind of the ancients is most clearly exhibited in the orgiastic rites connected with the initiations, and in what is symbolically acted in the religious services.

'For instance, not to digress far from our present subjects, they do not suppose nor admit any intercourse between Hera and Dionysus; and they guard against combining their worship; and their priestesses at Athens, they say, do not speak to each other when they meet, nor is ivy ever brought into the precincts of Hera, not because of their fabulous and nonsensical jealousies, but because the goddess presides over marriage and bridal processions, and drunkenness is unbecoming to bridegrooms, and most unbefitting to a marriage feast, as Plato says: for the drinking of strong wine causes disorder both in body and soul, whereby what is sown and conceived being shapeless and misplaced does not take root well. Again, those who sacrifice to Hera do not consecrate the gall, but bury it beside the altar, meaning that the wedded life of wife and husband ought to be free from anger and wrath, and undisturbed by rage and bitterness.

'This symbolical style is more common in the tales and legends. As for instance, they relate that Hera ...

'Such then is the legend: and the explanation of it is as follows. The variance and quarrel of Hera and Zeus is nothing else than the distemper and confusion of the elements, when they no longer bear a due proportion to each other in the cosmos, but disproportion and roughness arise, and they have a desperate fight and dissolve their connexion, and work the ruin of the universe.

If then Zeus, that is, the force of heat and fire, gives occasion to the variance, a drought overtakes the earth: but if it is on the part of Hera, that is, the element of rain and wind, that any outbreak or excess takes place, there comes a great flood, and deluges and overflows everything. And as something of this kind occurred about those times, and Boeotia especially had been deeply flooded, as soon as ever the plain emerged and the flood abated, the order which followed from the tranquillity of the atmosphere was called the agreement and reconciliation of the deities. The first of the plants that sprang up out of the earth was the oak; and men welcomed this, because it gave a permanent supply of food and safety....

THIS is what Plutarch says; and we learn from the statements which he sets before us, that even the wonderful and secret physiology of the Greek theology conveyed nothing divine, nor anything great and worthy of deity, and deserving of attention.

For you have heard Hera called at one time Gamelios, and a symbol of the joint life of husband and wife, and at another time the earth called Hera, and at another the element of water; and Dionysus translated into drunkenness, and Latona into night, and the sun into Apollo, and Zeus himself into the force of heat and fire.

So then the original indecency of the legends, and the physiological explanation, which is thought to be more respectable, led not up to any heavenly, intellectual, and divine powers, nor yet to rational and incorporeal essences, but the explanation itself led down again to drunkenness, and marriage feasts, and human passions, and reduced the parts of the cosmos to fire, and earth, and sun, and the other elements of matter, without introducing any other deity.

And Plato too knew this. In the Cratylus, at least, he expressly acknowledges that the first inhabitants of Greece knew nothing more than the visible parts of the cosmos, and supposed the luminaries in the heaven and the other phenomena to be the only gods.

So he speaks as follows word for word:

'It appears to me that the first inhabitants of Greece acknowledged no other gods than those whom many of the barbarians acknowledge now, namely, sun, and moon, and earth, and stars, and heaven.'...

Now we might reasonably ask, to which set of gods, will they say, do the forms belong which are engraven on their statues. Are they those of daemons? Or those of fire, and air, and earth, and water? Or likenesses of men and women, and shapes of brute animals and wild beasts?...

[S]urely true reason shouts and cries aloud, all but in actual speech, and testifies that they of whom we speak have been mortal men. And Plutarch with superabundant pains describes the particular character of their bodily shapes, in his work On Isis and the Gods of Egypt. Speaking as follows:

'The Egyptians narrate that in body Hermes was short-armed, and Typhon red in complexion, and Horus fair, and Osiris dark-skinned, as having been by nature men.'

Thus speaks Plutarch. So then their whole manufacture of gods consists of dead men; and their physical explanations are fictitious. For what need was there to model figures of men and women, when without them they could worship the sun and moon and the other elements of the cosmos?

To which of these two classes did they assign names of this kind, and with whom did they begin? I mean, for example, Hephaestus and Athena, and Zeus, and Poseidon, and Hera.

Were these in the first place names of the universal elements, which they have since ascribed to mortals, making them of the same name as the heavenly bodies? Or on the contrary, have they transferred the names in use among men to the natural substances?

But why should they address the natural elements of the universe by names of mortal men? And the mysteries belonging to each god, and the hymns, and songs, and the secrets of the initiatory rites,----do these introduce the symbols of the universal elements, or of the mortal men of old who had the same names with the gods?

Then as to wanderings, and drunken fits, and amours, and seduction of women, and plots against men, and countless things, which are in truth shameful and unseemly practices of mortal men, how could any one refer these to the universal elements, acts which bear upon their very face mortality and human passion?

So that from all these proofs this wonderful and noble physiology is convicted of having no connexion with truth, and containing nothing really divine, but possessing only a forced and counterfeit solemnity of external utterance...

After we have given so many proofs in confutation of their inconsistent theology, both the more mythical so-called, and that which is forsooth of a higher and more physical kind which the ancient Greeks and Egyptians were shown to magnify, it is time to survey also the refinements of the younger generations who make a profession of philosophy in our own time: for these have endeavoured to combine the doctrines concerning a creative mind of the universe, and those concerning incorporeal ideas and intelligent and rational powers,----doctrines invented long ages afterwards by Plato, and thought out with accurate reasonings,----with the theology of the ancients, exaggerating with yet greater conceit their promise concerning the legends. Listen then to their physiology also, and observe with what boastfulness it has been published by Porphyry.

-- Praeparatio Evangelica (Preparation for the Gospel), by Eusebius of Caesarea

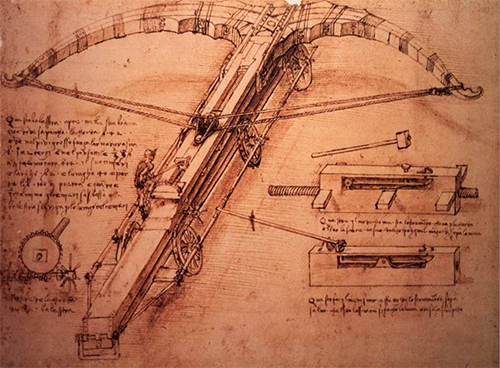

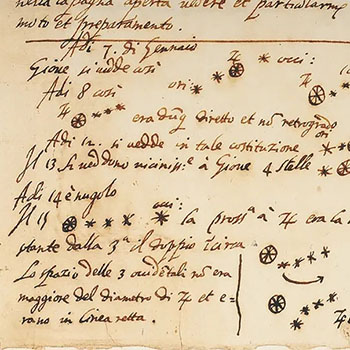

Annotations recording Galileo's discovery of the four moons of Jupiter, from the single leaf manuscript in our collection. (University of Michigan Library) Credit: University of Michigan Library

A prized manuscript in the University of Michigan library that was believed to have been written by the famed Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei is a forgery, the university said.

The one-page document known as the "Galileo manuscript" can't be traced to any earlier than 1930 and was likely written by the notorious Italian forger Tobia Nicotra, it said in a statement.

Tobia Nicotra was a prolific Italian forger who produced counterfeit works of artists in various disciplines. In 1937, he was described as "the most proficient forger of autographs". He may have produced as many as 600 forgeries before he was caught.

During the 1920s, the works of Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini were popular in the United States and had "so important a role in the country's musical life" that during Nicotra's visit to the United States starting in the late 1920s, he capitalized on the popularity by writing a biography of the conductor. His 1929 manuscript was in Italian, but it was published only in English: chapter 22 by Alfred A. Knopf with translation provided by Irma Brandeis and H. D. Kahn. It was rife with mistakes and has been described as "superficial" and containing "invented conversations". In 1932, he returned to the United States leading a salon orchestra impersonating Riccardo Drigo, an Italian composer who had died in 1930.

Nicotra produced forged manuscripts for various artists, including a poem by Torquato Tasso, the four-page musical manuscript Baci amorosi e cari attributed to Mozart, and works by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. He attributed four of his forged manuscripts to Pergolesi, though his attempts to imitate the composer's handwriting were not entirely successful. Two of these were described by music historian Barry S. Brooks as "awful" and written by a "totally unmusical" forger. He forged at least two manuscripts he ascribed to Handel: an aria he stated was from Handel's Italian period; and an air from the 1741 oratorio Messiah. Other musical forgeries he created were attributed to Gluck, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Richard Wagner.

His forgeries of composer autographs were described as "convincingly executed" by Harry Haskell. He achieved this by visiting libraries in Milan housing historical manuscripts, tearing out flyleaves (blank pages at the front or back of books) on which he would then add autographs. He wrote on this laid paper with a quill using iron-gall ink, which imparted the forged documents with an air of legitimacy. He brought the poem manuscript he forged and attributed to Tasso to an expert, stating he thought it might be a forgery; he was told it was authentic.

He also created forgeries of letters and other documents purportedly written by famous historical figures, including Christopher Columbus, Leonardo da Vinci, Abraham Lincoln, the Marquis de Lafayette, Martin Luther, Michelangelo, and George Washington. Major institutions purchased some of his forgeries, including the Library of Congress which in 1928 bought several Mozart autographs for $60 (equivalent to $947 in 2021) that experts had "accepted as genuine".

With the income he earned from the sale of his forgeries, Nicotra rented seven apartments in Milan, each for a mistress.

Many of his forgeries were sold in the United States during his visits in the 1920s and early 1930s. Forged Pergolesi autographs were sold to the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Opera, and even to the library in Pergolesi's hometown of Pergola. Walter Toscanini, son of Arturo and an authority in antiquarian manuscripts, bought a Mozart manuscript from Nicotra for 2,700 lire. Upon inspection, he suspected it to be a forgery and sent it to Mozarteum University Salzburg, where an historian verified it as authentic. Toscanini later determined it was a forgery, and with Milanese detective Giorgio Florita was able to catch Nicotra selling forgeries to Milanese publishing house Hopeli. Nicotra was eventually arrested for failing to provide an identity document upon request; a search yielded a forged identity document with his photograph and Drigo's name.

On 9 November 1934 he was sentenced to two years in prison and fined 2,400 lire (equivalent to £5,698,202 in 2020), based on testimony by Walter Toscanini and librarians from Milan whose testimony described the ruined manuscripts in their libraries. Police who had arrested him testified that at the time of his arrest he had autograph forgeries in progress at his workshop, including those for Christopher Columbus, Warren G. Harding, Tadeusz Kościuszko, Leonardo da Vinci, Abraham Lincoln, the Marquis de Lafayette, Martin Luther, Michelangelo, and George Washington. Nicotra was paroled early by the National Fascist Party that ruled the Kingdom of Italy to forge signatures for them.

In August 2022, a Galileo Galilei manuscript at the University of Michigan Library that had been described as "one of the great treasures" held in its collection was identified as a Nicotra forgery.

-- Tobia Nicotra, by Wikipedia

An investigation was launched after Nick Wilding, a professor of history at Georgia State University, contacted the university's curator, Pablo Alvarez. Wilding questioned the manuscript's watermark and provenance and shared serious doubts about its authenticity.

"Wilding concluded that our Galileo manuscript is a 20th-century fake executed by the well-known forger Tobia Nicotra," the university said. "After our own experts studied his most compelling evidence -- about the paper and provenance -- and reexamined the manuscript, we agreed with his conclusion."

Among the aspects Wilding questioned was the paper itself, particularly the monograms in the paper's watermark which date the paper to no earlier than the 18th century, the university said.

Nicotra was jailed for two years in 1934 for forgery, including Galileo documents, the statement noted.

The university is now reconsidering the manuscript's role in its collection.[!!!]

A portrait of Galileo Galilei painted in 1636. Credit: Imagno/Getty Images

Before the forgery determination, the document was described by the university as "one of the great treasures of the University of Michigan Library."

It purported to show notes recording Galileo's discovery of Jupiter's four moons.

"This was the first observational data that showed objects orbiting a body other than the Earth," the university's description of the manuscript states. "It reflects a pivotal moment in Galileo's life that helped to change our understanding of the universe."

The astronomer, who died in 1642, invented the telescope -- among many other achievements -- which enabled him to discover that Jupiter has moons. He became the foremost advocate of Copernican astronomy, which denied that the earth was the fixed center of the universe.

The University of Michigan acquired the manuscript in 1938 after it was bequeathed to the library by a Detroit businessman, Tracy McGregor, who was a collector of books and manuscripts, it said.

When McGregor obtained it, the document had been authenticated by Cardinal Pietro Maffi, who was the Archbishop of Pisa and who "compared this leaf with a Galileo autograph letter in his collection," the university said.

His Eminence Pietro Maffi, Archbishop of Pisa

Pietro Maffi (12 October 1858 – 17 March 1931) was an Italian Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Archbishop of Pisa from 1903 until his death, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1907.

Born in Corteolona, Pietro Maffi studied at the seminary in Pavia (from where he obtained his doctorate in theology) before being ordained to the priesthood in 1881. He was raised to the rank of Privy Chamberlain of His Holiness that same year, and taught philosophy and sciences at the Pavia seminary, of which he was also rector. Maffi founded the meteorological observatory and the Museum of Natural History of Pavia, as well as serving as editor and director of Rivista di scienze fisiche e matematiche. Maffi was later named Pro-Vicar General of Pavia and pro-synodal examiner, doctor honoris causa of theological college of Parma, and a supernumerary member of its scientific academy. In 1901, Maffi was made Vicar General of Ravenna and the prefect of its seminary's studies, becoming Apostolic Administrator of the archdiocese on 26 April 1902.

On 9 June 1902 Maffi was appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Ravenna and Titular Bishop of Caesarea in Mauretania by Pope Leo XIII. He received his episcopal consecration on the following 11 June from Cardinal Lucido Parocchi, with Archbishops Felix-Marie de Neckere and Diomede Panici serving as co-consecrators, at the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. Maffi was later advanced to Archbishop of Pisa on 22 June 1903. In addition to his pastoral duties, he was named director and administrator of the Vatican Observatory on 30 November 1904.

Pope Pius X created him Cardinal Priest of San Crisogono in the consistory of 15 April 1907. Maffi participated in and was a chief candidate in the 1914 papal conclave, which selected Pope Benedict XV.

During World War I, Maffi was known as the "War Cardinal" for his support of a fight-to-the-finish policy.

He also participated in the 1922 conclave, which selected Pope Pius XI. In a 1925 pastoral letter, the Archbishop issued a scathing attack on the Fascist government, which subsequently halted the letter's publication.

A close friend of the Royal Family, in 1930, he presided at the marriage of Crown Prince Umberto of Italy and Princess Marie-José of Belgium. The Cardinal continued to write numerous scientific and astronomical works, the best known of which is Nei cieli. His love for science once provoked Pisa's outrage, when Maffi proposed to erect a statue of Galileo Galilei, the scientist condemned by the Inquisition as a heretic.

Maffi died in Pisa, at age 72. He is buried at the Cathedral of Pisa.

-- Pietro Maffi, by Wikipedia

'Ptolemy too, the son of Agesarchus, in his first book concerning Philopator says that Cinyras and the descendants of Cinyras are buried in Paphos in the temple of Aphrodite.'Were I, however, to go over all the tombs which are worshipped by you, "all time would not suffice for me to tell"; [Homer, Od. xx. 351] while you, if no shame for these audacities steals over you, may wander round with your faith in the dead, utterly dead yourselves:

"Ah! wretched men, what evil doom is this?"

A little further on he says:'Another new god the Roman Emperor has deified with great solemnity in Egypt, and almost in Greece; his favourite Antinous, who was extremely beautiful, was deified by him, as Ganymede was by Zeus.

'For lust, when free from fear, is not easily restrained: and men now celebrate the sacred nights of Antinous, the shame of which was known to the lover who shared his vigils.'

He also adds:'And now the favourite's tomb is the temple and city of Antinous: for just as temples are held in reverence, so, I suppose, are tombs, pyramids, mausoleums, and labyrinths----other temples these of the dead, as those before mentioned were tombs of the gods.'

And again, a little further on:'Come then, let us also briefly make the round of your games, and put an end to these great sepulchral festivals, the Isthmian, Nemean, and Pythian, and besides these the Olympian. At Pytho the Pythian dragon is worshipped, and the festival of the serpent is proclaimed as the Pythia. At the Isthmus the sea cast up a miserable carcass, and the Isthmian games are a lamentation for Melicertes: at Nemea another child Archemorus is buried, and the boy's funeral games are called Nemea. Pisa is the tomb in your midst, O Panhellenes, of a Phrygian charioteer, and the Zeus of Phidias claims as his own the Olympian games, which are the funeral libations of Pelops.'

So speaks our author.

-- Praeparatio Evangelica (Preparation for the Gospel), by Eusebius of Caesarea