by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/26/20

An engraving of the Count of St. Germain by Nicolas Thomas made in 1783, after a painting then owned by the Marquise d'Urfe and now lost[1] Contained at the Louvre in France[2]

The Comte de Saint Germain (French pronunciation: [kɔ̃t də sɛ̃ ʒɛʁmɛ̃]; circa 1691 or 1712 – 27 February 1784)[3] was a European adventurer, with an interest in science, alchemy and the arts. He achieved prominence in European high society of the mid 1700s. Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel considered him to be "one of the greatest philosophers who ever lived".[4]

Prince Charles of Hesse, wearing the sash of the Order of the Elephant

Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel (Danish: Carl), German and Norwegian: Karl; 19 December 1744 – 17 August 1836) was a cadet member of the house of Hesse-Kassel and a Danish general field marshal. Brought up with relatives at the Danish court, he spent most of his life in Denmark, serving as royal governor of the twin duchies of Schleswig-Holstein from 1769 to 1836 and commander-in-chief of the Norwegian army from 1772 to 1814.

Charles was born in Kassel on 19 December 1744 as the second surviving son of Hesse-Kassel's then hereditary prince, the future Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel and his first wife Princess Mary of Great Britain. His mother was a daughter of King George II of Great Britain and Princess Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach and a sister of Queen Louise of Denmark.

His father, the future landgrave (who reigned from 1760 and died in 1785), left the family in 1747 and converted to Catholicism in 1749. In 1755 he formally ended the marriage with Mary. The grandfather, William VIII, Landgrave of Hesse, granted the county of Hanau and its revenues to Mary and her sons.

The young Prince Charles and his two brothers, William and Frederick, were raised by their mother and fostered by Protestant relatives since 1747.

In 1756, Mary moved to Denmark to look after her sister, Queen Louise of Denmark's children. She took her own children with her and they were raised at the royal court at Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen. The Hessian princes later remained in Denmark, becoming important lords and royal functionaries. Only the eldest brother William returned to Hesse, in 1785, upon ascending the landgraviate.

Charles began a military career in Denmark. In 1758 he was appointed colonel, at the age of 20 major general and in 1765 was put in charge of the artillery. After his cousin, King Christian VII, acceded to the throne in 1766, he was appointed lieutenant general, commander of the Royal Guard, knight of the Order of the Elephant and member of the Privy Council.

In 1766, he was appointed Governor-General of Norway as successor to Jacob Benzon (1688–1775). He held the position until 1768 but which remained mostly titular, as he never went to Norway during this period.

In 1763, his elder brother William married their first cousin, Danish Princess Caroline. Charles followed suit on 30 August 1766 at Christiansborg Palace — his wife was Louise of Denmark, and Charles thus became brother-in-law to his cousin, King Christian VII of Denmark. The marriage took place despite advice given against it, due to many accusations of debauchery by Prince Charles and the poor influence he had on the King.

Shortly after, Charles fell into disfavour at court, and in early 1767 he and Louise left Copenhagen to live with his mother in the county of Hanau. They would have their first child, Marie Sophie, there in 1767 and then their second child, William, in 1769.

Rumpenheim Palace, Offenbach

In 1768, Charles purchased the landed property and village of Offenbach-Rumpenheim from the Edelsheim family. In 1771 he had the manor expanded into a castle and princely seat. His mother Mary lived in the palace until her death in 1772. In 1781, Charles sold the Rumpenheim Palace to his younger brother, Frederick.

In 1769, Prince Charles of Hesse was appointed royal Governor of the twin duchies of Schleswig and Holstein (initially only the royal share, so-called Holstein-Glückstadt before in 1773 the king also acquired the ducal share in Holstein) on behalf of the government of his brother-in-law, King Christian VII of Denmark and Norway. Charles took up residence at Gottorp Castle in Schleswig with his family. They would have their third child Frederick there in 1771....

In September 1772, Charles was appointed commander-in-chief of the Norwegian army and he and Louise moved to Christiana. The assignment was a consequence of the coup d'état of King Gustav III of Sweden on 19 August 1772 and the subsequent prospect of war with Sweden. While in Norway, Princess Louise gave birth to their fourth child Juliane in 1773. Even though Charles returned to Schleswig-Holstein in 1774, he continued to function as commander-in-chief of the Norwegian army until 1814. At the time of his return from Norway, he was appointed field marshal.

During the War of the Bavarian Succession in 1778-79, he acted as a volunteer in the army of Frederick the Great and gained the trust of the Prussian king. Once, when Frederick was speaking against Christianity, he noticed a lack of sympathy of Charles' part. In response to an inquiry from the king, Charles said, "Sire, I am not more sure of having the honour of seeing you, than I am that Jesus Christ existed and died for us as our Saviour on the cross." After a moment of surprised silence, Frederick declared, "You are the first man who has ever declared such a belief in my hearing."

In 1788, the Swedish attack on Russia during the Russo Swedish War forced Denmark-Norway to declare war on Sweden in accordance with its 1773 treaty obligations to Russia. Prince Charles was put in command of a Norwegian army which briefly invaded Sweden through Bohuslän and won the Battle of Kvistrum Bridge. The army was closing in on Gothenburg, when peace was signed on 9 July 1789 following the diplomatic intervention of Great Britain and Prussia, bringing this so-called Lingonberry War to an end...

Charles was a remarkable patron of theater and opera. He had his own court theater in Schleswig, and he involved himself extensively in its operations....

In 1814 he was appointed general field marshal, and in 1816 Grand Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog.The Order of the Dannebrog (Danish: Dannebrogordenen) is a Danish order of chivalry instituted in 1671 by Christian V. Until 1808, membership in the order was limited to fifty members of noble or royal rank, who formed a single class known as White Knights to distinguish them from the Blue Knights who were members of the Order of the Elephant. In 1808, the Order was reformed and divided into four classes.

The Grand Commander class is reserved to persons of princely origin. It is awarded only to royalty with close family ties with the Danish Royal House.

-- Order of the Dannebrog, by Wikipedia

Prince Charles died on 17 August 1836 in the castle of Louisenlund in Güby, Schleswig.

-- Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, by Wikipedia

St. Germain used a variety of names and titles, an accepted practice amongst royalty and nobility at the time. These include the Marquis de Montferrat, Comte Bellamarre, Chevalier Schoening, Count Weldon, Comte Soltikoff, Graf Tzarogy and Prinz Ragoczy.[5] In order to deflect inquiries as to his origins, he would make far-fetched claims, such as being 500 years old,[6] leading Voltaire to sarcastically dub him "The Wonderman" and that "He is a man who does not die, and who knows everything".[7] [8]

His real name is unknown while his birth and background are obscure, but towards the end of his life, he claimed that he was a son of Prince Francis II Rákóczi of Transylvania.

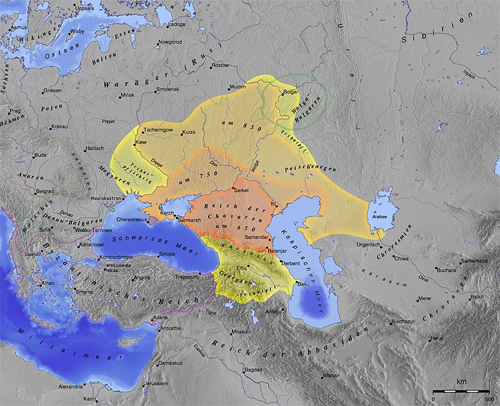

Francis II Rákóczi (Hungarian: II. Rákóczi Ferenc, Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈraːkoːt͡si ˈfɛrɛnt͡s]; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of the Hungarian uprising against the Habsburgs in 1703-11 as the prince (Hungarian: fejedelem) of the Estates Confederated for Liberty of the Kingdom of Hungary. He was also Prince of Transylvania, an Imperial Prince, and a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Today he is considered a national hero in Hungary.

His full title was: Franciscus II. Dei Gratia Sacri Romani Imperii & Transylvaniae princeps Rakoczi. Particum Regni Hungariae Dominus & Siculorum Comes, Regni Hungariae Pro Libertate Confoederatorum Statuum necnon Munkacsiensis & Makoviczensis Dux, Perpetuus Comes de Saros; Dominus in Patak, Tokaj, Regécz, Ecsed, Somlyó, Lednicze, Szerencs, Onod.

His name is historically also spelled Rákóczy, in Hungarian: II. Rákóczi Ferenc, in Slovak: František II. Rákoci, in German: Franz II. Rákóczi, in Croatian: Franjo II. Rákóczy (Rakoci, Rakoczy), in Romanian: Francisc Rákóczi al II-lea, in Serbian Ференц II Ракоци.

-- Francis II Rákóczi, by Wikipedia

His name has occasionally caused him to be confused with Claude Louis, Comte de Saint-Germain, a noted French general.[9]

Background

The count claimed to be a son of Francis II Rákóczi, the Prince of Transylvania, which could possibly be unfounded.[10] However, this would account for his wealth and fine education.[11] The will of Francis II Rákóczi mentions his eldest son, Leopold George, who was believed to have died at the age of four.[11] The speculation is that his identity was safeguarded as a protective measure from the persecutions against the Habsburg dynasty.[11] At the time of his arrival in Schleswig in 1779, St. Germain told Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel that he was 88 years old.[12] This would place his birth in 1691, when Francis II Rákóczi was 15 years old.

St. Germain was supposedly educated in Italy by the last of the Medicis, Gian Gastone, his alleged mother's brother-in-law. He was believed to be a student at the University of Siena.[9] Throughout his adult life, he deliberately spun a confusing web to conceal his actual name and origins, using different pseudonyms in the different places of Europe that he visited.

The Marquis de Crequy declared that St. Germain was an Alsatian Jew, Simon Wolff by name, and was born at Strasbourg about the close of the 17th or the beginning of the 18th century; others insist that he was a Spanish Jesuit named Aymar; and others again intimate that his true title was the Marquis de Betmar, and that he was a native of Portugal. The most plausible theory, however, makes him the natural son of an Italian princess and fixes his birth at San Germano, in Savoy, about the year 1710; his ostensible father being one Rotondo, a tax-collector of that district.

— Phineas Taylor Barnum, The Humbugs of the World, 1886.

Historical figure

He appears to have begun to be known under the title of the Count of St Germain during the early 1740s.[13]

England

According to David Hunter, the count contributed some of the songs to L'incostanza delusa, an opera performed at the Haymarket Theatre in London on all but one of the Saturdays from 9 February to 20 April 1745.[9] Later, in a letter of December of that same year, Horace Walpole mentions the Count St. Germain as being arrested in London on suspicion of espionage (this was during the Jacobite rebellion of 1745), but released without charge:

The other day they seized an odd man, who goes by the name of Count St. Germain. He has been here these two years, and will not tell who he is, or whence, but professes [two wonderful things, the first] that he does not go by his right name; and the second that he never had any dealings with any woman – nay, nor with any succedaneum. He sings, plays on the violin wonderfully, composes, is mad, and not very sensible. He is called an Italian, a Spaniard, a Pole; a somebody that married a great fortune in Mexico, and ran away with her jewels to Constantinople; a priest, a fiddler, a vast nobleman. The Prince of Wales has had unsatiated curiosity about him, but in vain. However, nothing has been made out against him; he is released; and, what convinces me that he is not a gentleman, stays here, and talks of his being taken up for a spy.[14]

The Count gave two private musical performances in London in April and May 1749.[9] On one such occasion, Lady Jemima Yorke [Jemima Yorke, 2nd Marchioness Grey and Countess of Hardwicke (née Campbell; 9 October 1723 – 10 January 1797), was a British peeress.] described how she was 'very much entertain'd by him or at him the whole Time – I mean the Oddness of his Manner which it is impossible not to laugh at, otherwise you know he is very sensible & well-bred in conversation'.[9] She continued:

'He is an Odd Creature, and the more I see him the more curious I am to know something about him. He is everything with everybody: he talks Ingeniously with Mr Wray, Philosophy with Lord Willoughby, and is gallant with Miss Yorke, Miss Carpenter, and all the Young Ladies. But the Character and Philosopher is what he seems to pretend to, and to be a good deal conceited of: the Others are put on to comply with Les Manieres du Monde, but that you are to suppose his real characteristic; and I can't but fancy he is a great Pretender in All kinds of Science, as well as that he really has acquired an uncommon Share in some'.[9]

Walpole reports that St Germain:

'spoke Italian and French with the greatest facility, though it was evident that neither was his language; he understood Polish, and soon learnt to understand English and talk it a little [...] But Spanish or Portuguese seemed his natural language'.[15]

Walpole concludes that the Count was 'a man of Quality who had been in or designed for the Church. He was too great a musician not to have been famous if he had not been a gentleman'.[15] Walpole describes the Count as pale, with 'extremely black' hair and a beard. 'He dressed magnificently, [and] had several jewels' and was clearly receiving 'large remittances, but made no other figure'.[15]

France

St. Germain appeared in the French court around 1748. In 1749, he was employed by Louis XV for diplomatic missions.[16]

A mime and English comedian known as Mi'Lord Gower impersonated St. Germain in Paris salons. His stories were wilder than the real count's (he had advised Jesus, for example). Inevitably, hearsay of his routine got confused with the original.

Giacomo Casanova describes in his memoirs several meetings with the "celebrated and learned impostor". Of his first meeting, in Paris in 1757, he writes:

The most enjoyable dinner I had was with Madame de Robert Gergi, who came with the famous adventurer, known by the name of the Count de St. Germain. This individual, instead of eating, talked from the beginning of the meal to the end, and I followed his example in one respect as I did not eat, but listened to him with the greatest attention. It may safely be said that as a conversationalist he was unequalled.

St. Germain gave himself out for a marvel and always aimed at exciting amazement, which he often succeeded in doing. He was scholar, linguist, musician, and chemist, good-looking, and a perfect ladies' man. For a while he gave them paints and cosmetics; he flattered them, not that he would make them young again (which he modestly confessed was beyond him) but that their beauty would be preserved by means of a wash which, he said, cost him a lot of money, but which he gave away freely. He had contrived to gain the favour of Madame de Pompadour, who had spoken about him to the king, for whom he had made a laboratory, in which the monarch — a martyr to boredom — tried to find a little pleasure or distraction, at all events, by making dyes. The king had given him a suite of rooms at Chambord, and a hundred thousand francs for the construction of a laboratory, and according to St. Germain the dyes discovered by the king would have a materially beneficial influence on the quality of French fabrics.

This extraordinary man, intended by nature to be the king of impostors and quacks, would say in an easy, assured manner that he was three hundred years old, that he knew the secret of the Universal Medicine, that he possessed a mastery over nature, that he could melt diamonds, professing himself capable of forming, out of ten or twelve small diamonds, one large one of the finest water without any loss of weight. All this, he said, was a mere trifle to him. Notwithstanding his boastings, his bare-faced lies, and his manifold eccentricities, I cannot say I thought him offensive. In spite of my knowledge of what he was and in spite of my own feelings, I thought him an astonishing man as he was always astonishing me.[17]

Dutch Republic

In March 1760, at the height of the Seven Years' War, St. Germain travelled to The Hague. In Amsterdam, he stayed at the bankers Adrian and Thomas Hope and pretended he came to borrow money for Louis XV with diamonds as collateral.[18] He assisted Bertrand Philip, Count of Gronsveld starting a porcelain factory in Weesp as furnace and colour specialist.[19] St. Germain tried to open peace negotiations between Britain and France with the help of Duke Louis Ernest of Brunswick-Lüneburg. British diplomats concluded that St. Germain had the backing of the Duc de Belle-Isle and possibly of Madame de Pompadour, who were trying to outmanoeuvre the French Foreign Minister, the pro-Austrian Duc de Choiseul. However, Britain would not treat with St. Germain unless his credentials came directly from the French king. The Duc de Choiseul convinced Louis XV to disavow St. Germain and demand his arrest. Count Bentinck de Rhoon, a Dutch diplomat, regarded the arrest warrant as internal French politicking, in which Holland should not involve itself. However, a direct refusal to extradite St. Germain was also considered impolitic. De Rhoon, therefore, facilitated the departure of St. Germain to England with a passport issued by the British Ambassador, General Joseph Yorke. This passport was made out "in blank", allowing St. Germain to travel in May 1760 from Hellevoetsluis to London under an assumed name, showing that this practice was officially accepted at the time.[20]

From St. Peterburg, St. Germain travelled to Berlin, Vienna, Milan, Ubbergen, and Zutphen (June 1762),[21][22] Amsterdam (August 1762), Venice (1769), Livorno (1770), Neurenberg (1772), Mantua (1773), The Hague (1774), and Bad Schwalbach.

Death

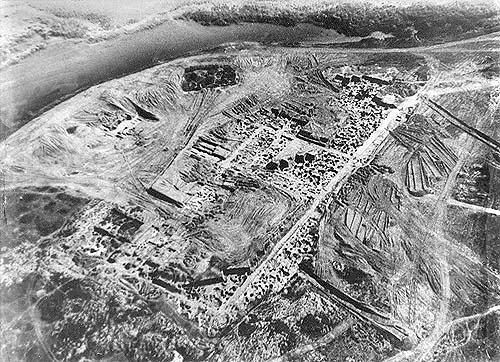

In 1779, St. Germain arrived in Altona in Schleswig, where he made an acquaintance with Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, who also had an interest in mysticism and was a member of several secret societies. The count showed the Prince several of his gems and he convinced the latter that he had invented a new method of colouring cloth. The Prince was impressed and installed the Count in an abandoned factory at Eckernförde he had acquired especially for the Count, and supplied him with the materials and cloths that St. Germain needed to proceed with the project.[23] The two met frequently in the following years, and the Prince outfitted a laboratory for alchemical experiments in his nearby summer residence Louisenlund, where they, among other things, cooperated in creating gemstones and jewelry. The prince later recounts in a letter that he was the only person in whom the count truly confided.[24] He told the prince that he was the son of the Transylvanian Prince Francis II Rákóczi, and that he had been 88 years of age when he arrived in Schleswig.[25]

The count died in his residence in the factory on 27 February 1784, while the prince was staying in Kassel, and the death was recorded in the register of the St. Nicolai Church in Eckernförde.[26] He was buried 2 March and the cost of the burial was listed in the accounting books of the church the following day.[27] The official burial site for the count is at Nicolai Church (German St. Nicolaikirche) in Eckernförde. He was buried in a private grave. On 3 April the same year, the mayor and the city council of Eckernförde issued an official proclamation about the auctioning off of the count's remaining effects in case no living relative would appear within a designated time period to lay claim on them.[28] Prince Charles donated the factory to the crown and it was afterward converted into a hospital.

Jean Overton Fuller found, during her research, that the count's estate upon his death was a packet of paid and receipted bills and quittances, 82 Reichsthalers and 13 shillings (cash), 29 various groups of items of clothing (this includes gloves, stockings, trousers, shirts, etc.), 14 linen shirts, eight other groups of linen items, and various sundries (razors, buckles, toothbrushes, sunglasses, combs, etc.). No diamonds, jewels, gold, or any other riches were listed, nor were kept cultural items from travels, personal items (like his violin), or any notes of correspondence.[29]

Music by the Count

The following list of music comes from Appendix II from Jean Overton Fuller's book The Comte de Saint Germain.[30]

Trio Sonatas

Six sonatas for two violins with a bass for harpsichord or violoncello:

• Op.47 I. F Major, 4/4, Molto Adagio

• Op.48 II. B Flat Major, 4/4, Allegro

• Op.49 III. E Flat Major, 4/4, Adagio

• Op.50 IV. G Minor, 4/4, Tempo giusto

• Op.51 V. G Major, 4/4, Moderato

• Op.52 VI. A Major, 3/4, Cantabile lento

Violin solos

Seven solos for a violin:

• Op.53 I. B Flat Major, 4/4, Largo

• Op.54 II. E Major, 4/4, Adagio

• Op.55 III. C Minor, 4/4, Adagio

• Op.56 IV. E Flat Major, 4/4, Adagio

• Op.57 V. E Flat Major, 4/4, Adagio

• Op.58 VI. A Major, 4/4, Adagio

• Op.59 VII. B Flat Major, 4/4, Adagio

English songs

• Op.4 The Maid That's Made For Love and Me (O Wouldst Thou Know What Sacred Charms). E Flat Major (marked B Flat Major), 3/4

• Op.7 Jove, When He Saw My Fanny's Face. D Major, 3/4

• Op.5 It Is Not That I Love You Less. F Major, 3/4

• Op.6 Gentle Love, This Hour Befriend Me. D Major, 4/4

Italian arias

Numbered in order of their appearance in the Musique Raisonnee, with their page numbers in that volume, * Marks those performed in L'Incostanza Delusa and published in the Favourite Songs[31] from that opera.

• Op.8 I. Padre perdona, oh! pene, G Minor, 4/4, p. 1

• Op.9 II. Non piangete amarti, E Major, 4/4, p. 6

• Op.10 III. Intendo il tuo, F Major, 4/4, p. 11

• Op.1 IV. Senza pieta mi credi*, G Major, 6/8 (marked 3/8 but there are 6 quavers to the bar), p. 16

• Op.11 V. Gia, gia che moria deggio, D Major, 3/4, p. 21

• Op.12 VI. Dille che l'amor mio*, E Major, 4/4, p. 27

• Op.13 VII. Mio ben ricordati, D Major, 3/4, p. 32

• Op.2 VIII. Digli, digli*, D Major, 3/4, p. 36

• Op.3 IX. Per pieta bel Idol mio*, F Major, 3/8, p. 40

• Op.14 X. Non so, quel dolce moto, B Flat Major, 4/4, p. 46

• Op.15 XI. Piango, e ver, ma non procede, G minor, 4/4, p. 51

• Op.16 XII. Dal labbro che t'accende, E Major, 3/4, p. 56

• Op.4/17 XIII. Se mai riviene, D Minor, 3/4, p. 58

• Op.18 XIV. Parlero non e permesso, E Major, 4/4, p. 62

• Op.19 XV. Se tutti i miei pensieri, A Major, 4/4, p. 64

• Op.20 XVI. Guadarlo, guaralo in volto, E Major, 3/4, p. 66

• Op.21 XVII. Oh Dio mancarmi, D Major, 4/4, p. 68

• Op.22 XVIII. Digli che son fedele, E Flat Major, 3/4, p. 70

• Op.23 XIX. Pensa che sei cruda, E Minor, 4/4, p. 72

• Op.24 XX. Torna torna innocente, G Major, 3/8, p. 74

• Op.25 XXI. Un certo non so che veggo, E Major, 4/4, p. 76

• Op.26 XXII. Guardami, guardami prima in volto, D Major, 4/4, p. 78

• Op.27 XXIII. Parto, se vuoi cosi, E Flat Major, 4/4, p. 80

• Op.28 XXIV. Volga al Ciel se ti, D Minor, 3/4, p. 82

• Op.29 XXV. Guarda se in questa volta, F Major, 4/4, p. 84

• Op.30 XXVI. Quanto mai felice, D Major, 3/4, p. 86

• Op.31 XXVII. Ah che neldi'sti, D Major, 4/4, p. 88

• Op.32, XXVIII. Dopp'un tuo Sguardo, F Major, 3/4, p. 90

• Op.33 XXIX. Serbero fra'Ceppi, G major, 4/4, 92

• Op.34 XXX. Figlio se piu non vivi moro, F Major, 4/4, p. 94

• Op.35 XXXI. Non ti respondo, C Major, 3/4, p. 96

• Op.36 XXXII. Povero cor perche palpito, G Major, 3/4, p. 99

• Op.37 XXXIII. Non v'e piu barbaro, C Minor, 3/8, p. 102

• Op.38 XXXIV. Se de'tuoi lumi al fuoco amor, E major, 4/4, p. 106

• Op.39 XXXV. Se tutto tosto me sdegno, E Major, 4/4, p. 109

• Op.40 XXXVI. Ai negli occhi un tel incanto, D Major, 4/4 (marked 2/4 but there are 4 crochets to the bar), p. 112

• Op.41 XXXVII. Come poteste de Dio, F Major, 4/4, p. 116

• Op.42 XXXVIII. Che sorte crudele, G Major, 4/4, p. 119

• Op.43 XXXIX. Se almen potesse al pianto, G Minor, 4/4, p. 122

• Op.44 XXXX. Se viver non posso lunghi, D Major, 3/8, p. 125

• Op.45 XXXXI. Fedel faro faro cara cara, D Major, 3/4, p. 128

• Op.46 XXXXII. Non ha ragione, F Major, 4/4, p. 131

Literature about the Count

Biographies

The best-known biography is Isabel Cooper-Oakley's The Count of St. Germain (1912), which gives a satisfactory biographical sketch. It is a compilation of letters, diaries, and private records written about the count by members of the French aristocracy who knew him in the 18th century. Another interesting biographical sketch can be found in The History of Magic, by Eliphas Levi, originally published in 1913.[32]

Numerous French and German biographies also have been published, among them Der Wiedergänger: Das zeitlose Leben des Grafen von Saint-Germain by Peter Krassa, Le Comte de Saint-Germain by Marie-Raymonde Delorme, and L'énigmatique Comte De Saint-Germain by Pierre Ceria and François Ethuin. In his work Sages and Seers (1959), Manly Palmer Hall refers to the biography Graf St.-Germain by E. M. Oettinger (1846).[33]

Books attributed to the Count

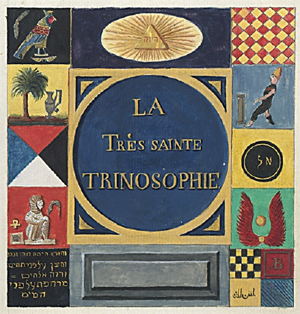

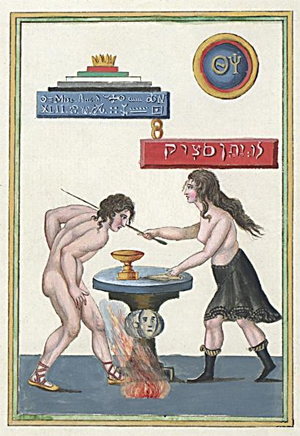

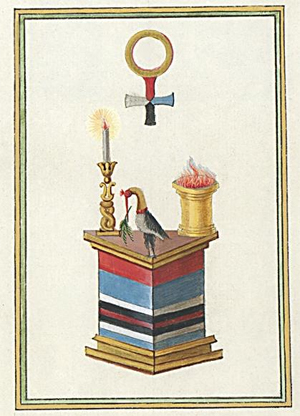

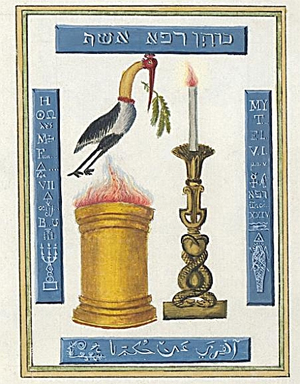

Discounting the snippets of political intrigue, a few musical pieces, and one mystical poem, there are only two pieces of writing attributed to the Count: La Très Sainte Trinosophie and the untitled Triangular Manuscript.

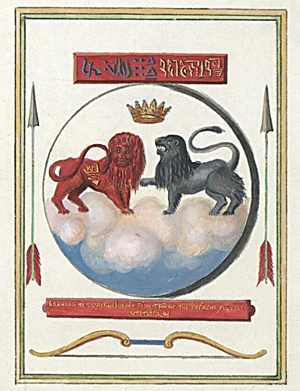

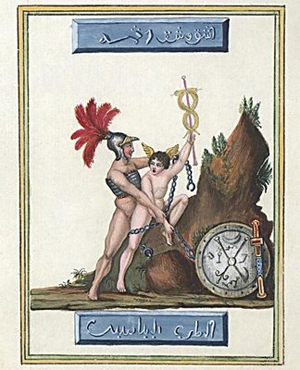

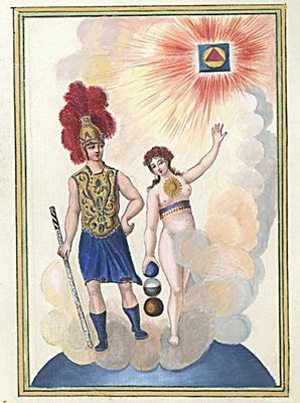

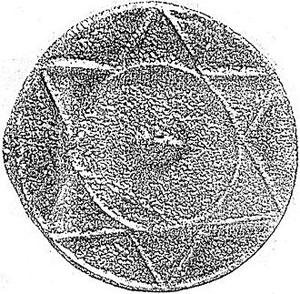

The first book attributed to the Count of Saint Germain is La Très Sainte Trinosophie (The Most Holy Trinosophia), a beautifully illustrated 18th century manuscript that describes in symbolic terms a journey of spiritual initiation or an alchemical process, depending on the interpretation. This book has been published several times, most notably by Manly P. Hall, in Los Angeles, California, in 1933. The attribution to St. Germain rests on a handwritten note scrawled inside the cover of the original manuscript stating that this was a copy of a text once in St. Germain's possession.[11] However, despite Hall's elaborate introduction describing the Count's legend, The Most Holy Trinosophia shows no definitive connection to him.

La Très Sainte Trinosophie, The Most Holy Trinosophia, or The Most Holy Threefold Wisdom, is a French esoteric book, allegedly authored by Alessandro Cagliostro or the Count of St. Germain. Due to the dearth of evidence of authorship, however, there is significant doubt surrounding the subject. Dated to the late 18th century, the 96-page book is divided into twelve sections representing the twelve zodiacal signs. The veiled content is said to refer to an allegorical initiation, detailing many kabbalistic, alchemical and masonic mysteries. The original MS 2400 at the Library of Troyes is richly illustrated with numerous symbolical plates....

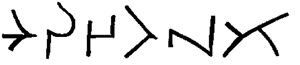

Manly Palmer Hall... cites Dr. Edward C. Getsinger, "an eminent authority on ancient alphabets and languages," in emphasizing that La Très Sainte Trinosophie is couched in secret codes intended to conceal its contents from the profane.In all my twenty years of experience as a reader of archaic writings I have never encountered such ingenious codes and methods of concealment as are found in this manuscript. In only a few instances are complete phrases written in the same alphabet; usually two or three forms of writing are employed, with letters written upside down, reversed, or with the text written backwards. Vowels are often omitted, and at times several letters are missing with merely dots to indicate their number. Every combination of hieroglyphics seemed hopeless at the beginning, yet, after hours of alphabetic dissection, one familiar word would appear. This gave a clue as to the language used, and established a place where word combination might begin, and then a sentence would gradually unfold.

The various texts are written in Chaldean Hebrew, Ionic Greek, Arabic, Syriac, cuneiform, Greek hieroglyphics, and ideographs. The keynote throughout this material is that of the approach of the age when the Leg of the Grand Man and the Waterman of the Zodiac shall meet in conjunction at the equinox and end a grand 400,000-year cycle. This points to a culmination of eons, as mentioned in the Apocalypse: "Behold! I make a new heaven and a new earth," meaning a series of new cycles and a new humanity.

The personage who gathered the material in this manuscript was indeed one whose spiritual understanding might be envied. He found these various texts in different parts of Europe, no doubt, and that he had a true knowledge of their import is proved by the fact that he attempted to conceal some forty fragmentary ancient texts by scattering them within the lines of his own writing. Yet his own text does not appear to have any connection with these ancient writings. If a decipherer were to be guided by what this eminent scholar wrote he would never decipher the mystery concealed within the cryptic words. There is a marvelous spiritual story written by this savant, and a more wonderful one he interwove within the pattern of his own narrative. The result is a story within a story.

-- The Most Holy Trinosophia, by Wikipedia

The second work attributed to St. Germain is the untitled 18th century manuscript in the shape of a triangle. The two known copies of the Triangular Manuscript exist as Hogart Manuscript 209 and 210 (MS 209 and MS 210). Both currently reside in the Manly Palmer Hall Collection of Alchemical Manuscripts at the Getty Research Library.[34] Nick Koss decoded and translated this manuscript in 2011 and it was published as The Triangular Book of St. Germain by Ouroboros Press in 2015.[35] Unlike the first work, it mentions St. Germain directly as its originator. The book describes a magical ritual by which one can perform the two most extraordinary feats that characterized the legend of Count of St. Germain, namely procurement of great wealth and extension of life.

In Theosophy

Main article: St. Germain (Theosophy)

Myths, legends, and speculations about St. Germain began to be widespread in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and continue today. They include beliefs that he is immortal, the Wandering Jew, an alchemist with the "Elixir of Life", a Rosicrucian, and that he prophesied the French Revolution. He is said to have met the forger Giuseppe Balsamo (alias Cagliostro) in London and the composer Rameau in Venice. Some groups honor Saint Germain as a supernatural being called an ascended master.

Madame Blavatsky and her pupil, Annie Besant, both claimed to have met the count, who was traveling under a different name.

In fiction

The count has inspired a number of fictional creations:

• The German writer Karl May wrote two stories with the Graf von Saint Germain appearing as antagonist: Aqua benedetta (1877) and its largely extended version Ein Fürst des Schwindels (1880).[36]

• The Comte is a significant character in the Victorian time-travel novella, A Peculiar Count In Time, by M.K. Beutymhill.

• The Comte is the main protagonist in an ongoing series of historical romance/horror novels by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro.

• The mystic in the Alexander Pushkin story "The Queen of Spades".

• The character of Agliè in the novel Foucault's Pendulum by Umberto Eco is an occultist who claims to be the Count St. Germain.[37]

• He is the main character of the historical mystery novel based on his early adventures, The Man Who Would Not Die, written by Paul Andrews. He is presented as the son of Prince Rákóczi.[38]

• He is a significant character in Diana Gabaldon's Outlander series, specifically 1992's Dragonfly in Amber, and an apparent time traveler in Gabaldon's spin-off novella, "The Space Between".

• In the novelization The Night Strangler, from the TV film of the same title, it is strongly hinted that the immortal villain, Dr. Richard Malcolm, is actually the Count St. Germain. When asked directly, Malcolm laughs ironically but does not deny it.[39]

• He is the main antagonist in The Ruby Red Trilogy, written by Kerstin Gier. He is the founder of a secret lodge which is controlling people with a time-travelling gene, and he is trying to gain immortality through the said time-travellers.

• In Kōta Hirano's Drifters, the character of count Saint Germi is inspired by him. He is voiced by Tomokazu Sugita in the anime adaptation.

• Robert Rankin's character Professor Slocombe, in the various books of The Brentford Trilogy, is often described as bearing an uncanny resemblance to the Comte; when the Professor annotates the Comte's ancient notebooks, even the handwriting is nearly identical. Another character, now quite old, born in the Victorian era, has stated that Professor Slocombe was an old man even then.

• He is introduced as a supporting character in the novel The Magician, the second book in the fantasy series The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel by Michael Scott.

• He is a character in Castlevania: Curse of Darkness, where he's a time traveler and voiced by Adam D. Clark. He fights with Zead, who is the avatar of Death.

• He is a character in Netflix's 2017 Castlevania (TV series), appearing as an itinerant magician in search of the "Infinite Corridor" voiced by Bill Nighy.

• He is mentioned in Raidou Kuzunoha vs. The Soulless Army as a time agent, yet the player never meets him.

• He is played by James Marsters in the TV series Warehouse 13. He is an immortal who used a ring with a gem from the Philosopher's stone used to revitalize plants and heal people to accumulate wealth throughout the ages. The ring was taken by Marie-Antoinette and buried in the Catacombs beneath Paris.

• Hoshino Katsura used him as inspiration for the character of the Millennium Earl in the manga series D. Gray Man.

• In Master of Mosquiton Mosquiton's enemy is an immortal demon loosely based on the Count of St. Germain.

• He is portrayed by Miya Rurika in the play Azure Moment by Takarazuka Revue.

• Prominent Bengali fiction author Shariful Hasan made the character Count Saint Germain in his Samvala Trilogy inspired by him.

• The visual novel Code: Realize − Guardian of Rebirth depicts him as an eccentric aristocrat hosting Arsène Lupin, Impey Barbicane, Victor Frankenstein, and Van Helsing in his manor.

• The character of Jack Elderflower in the novel Gather the Fortunes, by Bryan Camp.

• In the tabletop role-playing game Unknown Armies by John Scott Tynes and Greg Stolze, he is the First and Last Man, the only immortal character in the setting, whose lifespan encompasses the first and last lives of human beings.

• He appears as a playable character in the Japanese otome game "Ikemen Vampire" series of stories. In the series, he is the sire and the host for those who he has given a second lease in life including "Napoleon Bonaparte", "Isaac Newton", "Sir Arthur Conan Doyle", "Leonardo da Vinci", "William Shakespeare", "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart", "Vincent Van Gogh", "Theo Van Gogh", "Jeanne d'Arc" who is named as Jean d'Arc and is a man, and "Osamu Dazai" The series portrays him as a kind, mild-mannered, intelligent, respectable and respected nobleman of immeasurable wealth as well as a protective father or older sibling figure to all his residents including his human butler.

References

1. THE COUNT OF ST. GERMAIN, Johan Franco, Musical Quarterly (1950) XXXVI(4): 540-550

2. Hall, Manley P. (preface) The Music of the Comte de St.Germain Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, 1981

3. Isabel Cooper Oakley, p45

4. S. A. Le Landgrave Charles, Prince de Hesse, Mémoires de Mon Temps, p. 135. Copenhagen, 1861.

5. Spellings used are those given in The Comte de St. Germain by Isabel Cooper-Oakley

6. Oliver, George (1855). A Dictionary of Symbolic Masonry: Including the Royal Arch Degree; According to the System Prescribed by the Grand Lodge and Supreme Grand Chapter of England. Jno. W. Leonard. p. 10.

7. Comte de Saint-Germain (French adventurer) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-07.

8. Frederick II. "Correspondance avec M. de Voltaire." Oevres Posthumes de Frederic II. Tome XIV. Amsterdam, 1789. Pages 255 - 257

9. Hunter, David (2003). "Monsieur le Comte de Saint-Germain: The Great Pretender". The Musical Times. 144 (1885): 40. doi:10.2307/3650726. JSTOR 3650726.

10. The Comte de St. Germain by Isabel Cooper-Oakley. Milan, Italy: Ars Regia, 1912.

11. Franco, Johan (1950). "The Count of St. Germain". The Musical Quarterly. 36 (4): 540–550. doi:10.1093/mq/xxxvi.4.540. JSTOR 739641.

12. S. A. Le Landgrave Charles, Prince de Hesse, Mémoires de Mon Temps, p. 133. Copenhagen, 1861.

13. http://ichriss.ccarh.org/Germain.pdf

14. "Letter to Sir Horace Mann". Project Gutenberg. 9 December 1745.

15. The Yale edition of Horace Walpole correspondence (1712–1784), vol 26, pp20-21

16. Isabel Cooper Oakley, The Comte de St. Germain: the secret of kings (1912), p.94

17. "The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Memoires of Casanova, Complete, by Jacques Casanova de Seingalt". Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

18. Gedenkschriften van G.J. Hardenbroek, deel I, p. 160-161, 220-221

19. Forgotten Sources of Information about Dutch Porcelain by NANNE OTTEMA

20. Isabel Cooper Oakley, The Comte de St. Germain: the secret of kings (1912), pp.111-27 and Appendices

21. The Count of Saint-Germain by David Pratt

22. National Archives, p. 11

23. The memoirs of Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, (Mémories de mon temps. Dicté par S.A. le Landgrave Charles, Prince de Hesse. Imprimés comme Manuscrit, Copenhagen, 1861). von Lowzow, 1984, pp. 306-8.

24. Letter from Charles of Hesse-Kassel to Prince Christian of Hesse-Darmstadt, April 17, 1825. von Lowzow, 1984, p. 328.

25. von Lowzow, 1984, p. 309.

26. von Lowzow, 1984, p. 323.

27. 10 thaler for renting the plot for 30 years, 2 thaler for the gravedigger, and 12 marks to the bell-ringer. von Lowzow, 1984, p. 324.

28. Schleswig-Holsteinischen Anzeigen auf da Jahr 1784, Glückstadt, 1784, pp. 404, 451. von Lowzow, 1984, pp. 324-25.

29. Overton-Fuller, Jean. The Comte De Saint-Germain. Last Scion of the House of Rakoczy. London, UK: East-West Publications, 1988. Pages 290-296.

30. Overton-Fuller, Jean. The Comte De Saint-Germain. Last Scion of the House of Rakoczy. London, UK: East-West Publications, 1988. Pages 310-312.

31. Saint-Germain, Count de, ed. The Music of the Comte St.Germain. Edited by Manley Hall. Los Angeles, California: Philosophical Research Society, 1981.

32. Levi, Eliphas. The History of Magic. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1999. ISBN 0-87728-929-8.

33. Hall, Manly P. Sages and Seers. Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, 1959. ISBN 0-89314-393-6.

34. CIFA: Search Form Archived 12 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Archives.getty.edu:8082. Retrieved on 2011-05-07.

35. "TRIANGULAR BOOK OF ST. GERMAIN | Ouroboros Press". ouroboros-press.bookarts.org. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

36. Online texts of Aqua benedetta and Ein Fürst des Schwindels

37. Eco, U. Foucault's Pendulum. London: Random House, 2001. ISBN 978-0-09-928715-5.

38. Andrews, Paul The Man Who Would Not Die. Smashwords, 2014. ISBN 978-131-0547652.

39. Rice, Jeff. The Night Strangler. New York City: Pocket Books, 1974. ISBN 978-0671783525.

Further reading

• Marie Antoinette von Lowzow, Saint-Germain – Den mystiske greve, Dansk Historisk Håndbogsforlag, Copenhagen, 1984. ISBN 978-87-88742-04-6. (in Danish).

• Melton, J. Gordon Encyclopedia of American Religions 5th Edition New York:1996 Gale Research ISBN 0-8103-7714-4 ISSN 1066-1212 Chapter 18--"The Ancient Wisdom Family of Religions" Pages 151-158; see chart on page 154 listing Masters of the Ancient Wisdom; Also see Section 18, Pages 717-757 Descriptions of various Ancient Wisdom religious organizations

• Chrissochoidis, Ilias. "The Music of the Count of St. Germain: An Edition", Society for Eighteenth-Century Music Newsletter 16 (April 2010), [6–7].

• Fleming, Thomas. "The Magnificent Fraud." American Heritage, February 2006 (2006).

• Hausset, Madame du. "The Private Memoirs of Louis XV: Taken from the Memoirs of Madame Du Hausset, Lady's Maid to Madame De Pompadour." ed Nichols Harvard University, 1895.

• Hunter, David. "The Great Pretender." Musical Times, no. Winter 2003 (2003).

• Pope-Hennessey, Una. The Comte De Saint-Germain. Reprint ed, Secret Societies and the French Revolution. Together with Some Kindred Studies by Una Birch. Lexington, Kentucky: Forgotten Books, 1911.

• Saint-Germain, Count de, ed. The Music of the Comte St.Germain. Edited by Manley Hall. Los Angeles, California: Philosophical Research Society, 1981.

• Saint-Germain, Count de. The Most Holy Trinosophia. Forgotten Books, N.D. Reprint, 2008.

• Slemen, Thomas. Strange but True. London: Robinson Publishing, 1998.

• Walpole, Horace. "Letters of Horace Walpole." ed Charles Duke Yonge. New York: Putman's Sons, Dec. 9, 1745.

• d'Adhemar, Madame Comtesse le. "Souvenirs Sur Marie-Antoinette." Paris: Impremerie de Bourgogne et Martinet, 1836.

• Cooper-Oakley, Isabella. The Comte De Saint Germain, the Secret of Kings. 2nd ed. London: Whitefriars Press, 1912.

• SAINT GERMAIN ON ADVANCED ALCHEMY, by David Christopher Lewis, Meru press, ISBN 0981886353

External links

• The Comte de St. Germain (1912) by Isabel Cooper-Oakley, at sacred-texts.com