by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/13/21

The strange parallel between Buddhistic ritual, discipline, and costume, and those which especially claim the name of CATHOLIC in the Christian Church, has been often noticed; and though the parallel has never been elaborated as it might be, some of the more salient facts are familiar to most readers. Still many may be unaware that Buddha himself, Siddhárta the son of Súddodhana, has found his way into the Roman martyrology as a Saint of the Church.

In the first edition a mere allusion was made to this singular story, for it had recently been treated by Professor Max Müller, with characteristic learning and grace. (See Contemporary Review for July, 1870, p. 588.) But the matter is so curious and still so little familiar that I now venture to give it at some length.

The religious romance called the History of BARLAAM and JOSAPHAT was for several centuries one of the most popular works in Christendom. It was translated into all the chief European languages, including Scandinavian and Sclavonic tongues. An Icelandic version dates from the year 1204; one in the Tagal language of the Philippines was printed at Manilla in 1712.[2] The episodes and apologues with which the story abounds have furnished materials to poets and story-tellers in various ages and of very diverse characters; e.g. to Giovanni Boccaccio, John Gower, and to the compiler of the Gesta Romanorum, to Shakspere, and to the late W. Adams, author of the Kings Messengers. The basis of this romance is the story of Siddhárta.

The story of Barlaam and Josaphat first appears among the works (in Greek) of St. John of Damascus, a theologian of the early part of the 8th century, who, before he devoted himself to divinity had held high office at the Court of the Khalif Abu Jáfar Almansúr. The outline of the story is as follows:—

St. Thomas had converted the people of India to the truth; and after the eremitic life originated in Egypt many in India adopted it. But a potent pagan King arose, by name ABENNER, who persecuted the Christians and especially the ascetics. After this King had long been childless, a son, greatly desired, is born to him, a boy of matchless beauty. The King greatly rejoices, gives the child the name of JOSAPHAT, and summons the astrologers to predict his destiny. They foretell for the prince glory and prosperity beyond all his predecessors in the kingdom. One sage, most learned of all, assents to this, but declares that the scene of these glories will not be the paternal realm, and that the child will adopt the faith that his father persecutes.

This prediction greatly troubled King Abenner. In a secluded city he caused a splendid palace to be erected, within which his son was to abide, attended only by tutors and servants in the flower of youth and health. No one from without was to have access to the prince; and he was to witness none of the afflictions of humanity, poverty, disease, old age, or death, but only what was pleasant, so that he should have no inducement to think of the future life; nor was he ever to hear a word of CHRIST or His religion. And, hearing that some monks still survived in India, the King in his wrath ordered that any such, who should be found after three days, should be burnt alive.

The Prince grows up in seclusion, acquires all manner of learning, and exhibits singular endowments of wisdom and acuteness. At last he urges his father to allow him to pass the limits of the palace, and this the King reluctantly permits, after taking all precautions to arrange diverting spectacles, and to keep all painful objects at a distance. Or let us proceed in the Old English of the Golden Legend.[3] "Whan his fader herde this he was full of sorowe, and anone he let do make redy horses and joyfull felawshyp to accompany him, in suche wyse that nothynge dyshonest sholde happen to hym. And on a tyme thus as the Kynges sone wente he mette a mesell and a blynde man, and whã he sawe them he was abasshed and enquyred what them eyled. And his seruautes sayd: These ben passions that comen to men. And he demaunded yf the passyons came to all men. And they sayd nay. Thã sayd he, ben they knowen whiche men shall suffre…. And they answered, Who is he that may knowe ye aduentures of men. And he began to be moche anguysshous for ye incustomable thynge hereof. And another tyme he found a man moche aged, whiche had his chere frouced, his tethe fallen, and he was all croked for age…. And thã he demaunded what sholde be ye ende. And they sayd deth…. And this yonge man remembered ofte in his herte these thynges, and was in grete dyscõforte, but he shewed hy moche glad tofore his fader, and he desyred moche to be enformed and taught in these thyges." [Fol. ccc. lii.]

At this time BARLAAM, a monk of great sanctity and knowledge in divine things, who dwelt in the wilderness of Sennaritis, having received a divine warning, travels to India in the disguise of a merchant, and gains access to Prince Josaphat, to whom he unfolds the Christian doctrine and the blessedness of the monastic life. Suspicion is raised against Barlaam, and he departs. But all efforts to shake the Prince's convictions are vain. As a last resource the King sends for a magician called Theudas, who removes the Prince's attendants and substitutes seductive girls, but all their blandishments are resisted through prayer. The King abandons these attempts and associates his son with himself in the government. The Prince uses his power to promote religion, and everything prospers in his hand. Finally King Abenner is drawn to the truth, and after some years of penitence dies. Josaphat then surrenders the kingdom to a friend called Barachias, and proceeds into the wilderness, where he wanders for two years seeking Barlaam, and much buffeted by the demons. "And whan Balaam had accomplysshed his dayes, he rested in peas about ye yere of Our Lorde. cccc. &. Ixxx. Josaphat lefte his realme the xxv. yere of his age, and ledde the lyfe of an heremyte xxxv. yere, and than rested in peas full of vertues, and was buryed by the body of Balaam." [Fol. ccc. lvi.] The King Barachias afterwards arrives and transfers the bodies solemnly to India.

This is but the skeleton of the story, but the episodes and apologues which round its dimensions, and give it its mediaeval popularity, do not concern our subject. In this skeleton the story of Siddhárta, mutatis mutandis is obvious.

The story was first popular in the Greek Church, and was embodied in the lives of the saints, as recooked by Simeon the Metaphrast, an author whose period is disputed, but was in any case not later than 1150. A Cretan monk called Agapios made selections from the work of Simeon which were published in Romaic at Venice in 1541 under the name of the Paradise, and in which the first section consists of the story of Barlaam and Josaphat. This has been frequently reprinted as a popular book of devotion. A copy before me is printed at Venice in 1865.[4]

From the Greek Church the history of the two saints passed to the Latin, and they found a place in the Roman martyrology under the 27th November. When this first happened I have not been able to ascertain. Their history occupies a large space in the Speculum Historiale of Vincent of Beauvais, written in the 13th century, and is set forth, as we have seen, in the Golden Legend of nearly the same age. They are recognised by Baronius, and are to be found at p. 348 of "The Roman Martyrology set forth by command of Pope Gregory XIII., and revised by the authority of Pope Urban VIII., translated out of Latin into English by G.K. of the Society of Jesus…. and now re-edited … by W.N. Skelly, Esq. London, T. Richardson & Son." (Printed at Derby, 1847.) Here in Palermo is a church bearing the dedication Divo Iosaphat.

Professor Müller attributes the first recognition of the identity of the two stories to M. Laboulaye in 1859. But in fact I find that the historian de Couto had made the discovery long before.[5] He says, speaking of Budão (Buddha), and after relating his history:

"To this name the Gentiles throughout all India have dedicated great and superb pagodas. With reference to this story we have been diligent in enquiring if the ancient Gentiles of those parts had in their writings any knowledge of St. Josaphat who was converted by Barlam, who in his Legend is represented as the son of a great King of India, and who had just the same up-bringing, with all the same particulars, that we have recounted of the life of the Budão…. And as a thing seems much to the purpose, which was told us by a very old man of the Salsette territory in Baçaim, about Josaphat, I think it well to cite it: As I was travelling in the Isle of Salsette, and went to see that rare and admirable Pagoda (which we call the Canará Pagoda[6]) made in a mountain, with many halls cut out of one solid rock … and enquiring from this old man about the work, and what he thought as to who had made it, he told us that without doubt the work was made by order of the father of St. Josaphat to bring him up therein in seclusion, as the story tells. And as it informs us that he was the son of a great King in India, it may well be, as we have just said, that he was the Budão, of whom they relate such marvels." (Dec. V. liv. vi. cap. 2.)

Dominie Valentyn, not being well read in the Golden Legend, remarks on the subject of Buddha: "There be some who hold this Budhum for a fugitive Syrian Jew, or for an Israelite, others who hold him for a Disciple of the Apostle Thomas; but how in that case he could have been born 622 years before Christ I leave them to explain. Diego de Couto stands by the belief that he was certainly Joshua, which is still more absurd!" (V. deel, p. 374.)

[Since the days of Couto, who considered the Buddhist legend but an imitation of the Christian legend, the identity of the stories was recognised (as mentioned supra) by M. Edouard Laboulaye, in the Journal des Débats of the 26th of July, 1859. About the same time, Professor F. Liebrecht of Liége, in Ebert's Jahrbuch für Romanische und Englische Literatur, II. p. 314 seqq., comparing the Book of Barlaam and Joasaph with the work of Barthélemy St. Hilaire on Buddha, arrived at the same conclusion.

In 1880, Professor T.W. Rhys Davids has devoted some pages (xxxvi.-xli.) in his Buddhist Birth Stories; or, Jataka Tales, to The Barlaam and Josaphat Literature, and we note from them that: "Pope Sixtus the Fifth (1585-1590) authorised a particular Martyrologium, drawn up by Cardinal Baronius, to be used throughout the Western Church.". In that work are included not only the saints first canonised at Rome, but all those who, having been already canonised elsewhere, were then acknowledged by the Pope and the College of Rites to be saints of the Catholic Church of Christ. Among such, under the date of the 27th of November, are included "The holy Saints Barlaam and Josaphat, of India, on the borders of Persia, whose wonderful acts Saint John of Damascus has described. Where and when they were first canonised, I have been unable, in spite of much investigation, to ascertain. Petrus de Natalibus, who was Bishop of Equilium, the modern Jesolo, near Venice, from 1370 to 1400, wrote a Martyrology called Catalogus Sanctorum; and in it, among the 'Saints,' he inserts both Barlaam and Josaphat, giving also a short account of them derived from the old Latin translation of St. John of Damascus. It is from this work that Baronius, the compiler of the authorised Martyrology now in use, took over the names of these two saints, Barlaam and Josaphat. But, so far as I have been able to ascertain, they do not occur in any martyrologies or lists of saints of the Western Church older than that of Petrus de Natalibus. In the corresponding manual of worship still used in the Greek Church, however, we find, under 26th August, the name 'of the holy Iosaph, son of Abener, King of India.' Barlaam is not mentioned, and is not therefore recognised as a saint in the Greek Church. No history is added to the simple statement I have quoted; and I do not know on what authority it rests. But there is no doubt that it is in the East, and probably among the records of the ancient church of Syria, that a final solution of this question should be sought. Some of the more learned of the numerous writers who translated or composed new works on the basis of the story of Josaphat, have pointed out in their notes that he had been canonised; and the hero of the romance is usually called St. Josaphat in the titles of these works, as will be seen from the Table of the Josaphat literature below. But Professor Liebrecht, when identifying Josaphat with the Buddha, took no notice of this; and it was Professor Max Müller, who has done so much to infuse the glow of life into the dry bones of Oriental scholarship, who first pointed out the strange fact—almost incredible, were it not for the completeness of the proof—that Gotama the Buddha, under the name of St. Josaphat, is now officially recognised and honoured and worshipped throughout the whole of Catholic Christendom as a Christian saint!" Professor T.W. Rhys Davids gives further a Bibliography, pp. xcv.-xcvii.

M.H. Zotenberg wrote a learned memoir (N. et Ext. XXVIII. Pt. I.) in 1886 to prove that the Greek Text is not a translation but the original of the Legend. There are many MSS. of the Greek Text of the Book of Barlaam and Joasaph in Paris, Vienna, Munich, etc., including ten MSS. kept in various libraries at Oxford. New researches made by Professor E. Kuhn, of Munich (Barlaam und Joasaph. Eine Bibliographisch-literargeschichtliche Studie, 1893), seem to prove that during the 6th century, in that part of the Sassanian Empire bordering on India, in fact Afghanistan, Buddhism and Christianity were gaining ground at the expense of the Zoroastrian faith, and that some Buddhist wrote in Pehlevi a Book of Yûdâsaf (Bodhisatva); a Christian, finding pleasant the legend, made an adaptation of it from his own point of view, introducing the character of the monk Balauhar (Barlaam) to teach his religion to Yûdâsaf, who could not, in his Christian disguise, arrive at the truth by himself like a Bodhisatva. This Pehlevi version of the newly-formed Christian legend was translated into Syriac, and from Syriac was drawn a Georgian version, and, in the first half of the 7th century, the Greek Text of John, a monk of the convent of St. Saba, near Jerusalem, by some turned into St. John of Damascus, who added to the story some long theological discussions. From this Greek, it was translated into all the known languages of Europe, while the Pehlevi version being rendered into Arabic, was adapted by the Mussulmans and the Jews to their own creeds. (H. Zotenberg, Mém. sur le texte et les versions orientales du Livre de Barlaam et Joasaph, Not. et Ext. XXVIII. Pt. I. pp. 1-166; G. Paris, Saint Josaphat in Rev. de Paris, 1'er Juin, 1895, and Poèmes et Légendes du Moyen Age, pp. 181-214.)

Mr. Joseph Jacobs published in London, 1896, a valuable little book, Barlaam and Josaphat, English Lives of Buddha, in which he comes to this conclusion (p. xli.): "I regard the literary history of the Barlaam literature as completely parallel with that of the Fables of Bidpai. Originally Buddhistic books, both lost their specifically Buddhistic traits before they left India, and made their appeal, by their parables, more than by their doctrines. Both were translated into Pehlevi in the reign of Chosroes, and from that watershed floated off into the literatures of all the great creeds. In Christianity alone, characteristically enough, one of them, the Barlaam book, was surcharged with dogma, and turned to polemical uses, with the curious result that Buddha became one of the champions of the Church. To divest the Barlaam-Buddha of this character, and see him in his original form, we must take a further journey and seek him in his home beyond the Himalayas."

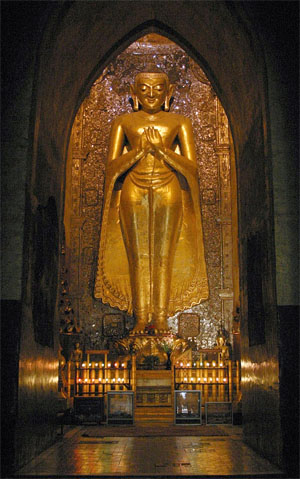

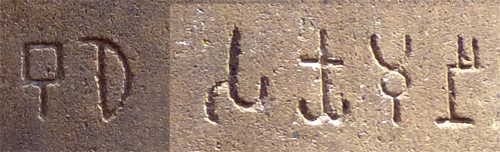

[Illustration: Sakya Muni as a Saint of the Roman Martyrology. "Wie des Kunigs Son in dem aufscziechen am ersten sahe in dem Weg eynen blinden und eyn aufsmörckigen und eyen alten krummen Man."[7]]

Professor Gaston Paris, in answer to Mr. Jacobs, writes (Poèmes et Lég. du Moyen Age, p. 213): "Mr. Jacobs thinks that the Book of Balauhar and Yûdâsaf was not originally Christian, and could have existed such as it is now in Buddhistic India, but it is hardly likely, as Buddha did not require the help of a teacher to find truth, and his followers would not have invented the person of Balauhar-Barlaam; on the other hand, the introduction of the Evangelical Parable of The Sower, which exists in the original of all the versions of our Book, shows that this original was a Christian adaptation of the Legend of Buddha. Mr. Jacobs seeks vainly to lessen the force of this proof in showing that this Parable has parallels in Buddhistic literature."—H.C.]

-- The Travels of Marco Polo, by Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition

A Christian depiction of Josaphat, 12th century manuscript

Barlaam and Josaphat are legendary Christian martyrs and saints. Their life story is very likely to have been based on the life of the Gautama Buddha.[1] It tells how an Indian king persecuted the Christian Church in his realm. When astrologers predicted that his own son would some day become a Christian, the king imprisoned the young prince Josaphat, who nevertheless met the hermit Saint Barlaam and converted to Christianity. After much tribulation the young prince's father accepted the Christian faith, turned over his throne to Josaphat, and retired to the desert to become a hermit. Josaphat himself later abdicated and went into seclusion with his old teacher Barlaam.[2] The tale derives from a second to fourth century Sanskrit Mahayana Buddhist text, via a Manichaean version,[3] then the Arabic Kitāb Bilawhar wa-Būd̠āsaf (Book of Bilawhar and Budhasaf), current in Baghdad in the eighth century, from where it entered into Middle Eastern Christian circles before appearing in European versions. The two were entered in the Eastern Orthodox calendar with a feast-day on 26 August,[4] and in the Roman Martyrology in the Western Church as "Barlaam and Josaphat" on the date of 27 November.[5]

Background: the Buddha

Depiction of a parable from Barlaam and Josaphat at the Baptistery of Parma, Italy

The story of Barlaam and Josaphat or Joasaph is a Christianized and later version of the story of Siddhartha Gautama, who became the Buddha.[6] In the Middle Ages the two were treated as Christian saints, being entered in the Greek Orthodox calendar on 26 August,[4] and in the Roman Martyrology in the Western Church as "Barlaam and Josaphat" on the date of 27 November.[5] In the Slavic tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church, these two are commemorated on 19 November (corresponding to 2 December on the Gregorian calendar).[7][8]

The first Christianized adaptation was the Georgian epic Balavariani dating back to the 10th century. A Georgian monk, Euthymius of Athos, translated the story into Greek, some time before he died in an accident while visiting Constantinople in 1028.[9] There the Greek adaptation was translated into Latin in 1048 and soon became well known in Western Europe as Barlaam and Josaphat.[10] The Greek legend of "Barlaam and Ioasaph" is sometimes attributed to the 7th century John of Damascus, but Conybeare argued it was transcribed by the Georgian monk Euthymius in the 11th century.[11]

The story of Barlaam and Josaphat was popular in the Middle Ages, appearing in such works as the Golden Legend, and a scene there involving three caskets eventually appeared, via Caxton's English translation of a Latin version, in Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice".[12] The poet Chardri produced an Anglo-Norman version, La vie de seint Josaphaz, in the 13th century.

Two Middle High German versions were produced: one, the "Laubacher Barlaam", by Bishop Otto II of Freising and another, Barlaam und Josaphat, a romance in verse, by Rudolf von Ems. The latter was described as "perhaps the flower of religious literary creativity in the German Middle Ages" by Heinrich Heine.[13]

The story of Josaphat was re-told as an exploration of free will[14] and the seeking of inner peace through meditation in the 17th century.[citation needed]

The legend

According to the legend, King Abenner or Avenier in India persecuted the Christian Church in his realm, founded by the Apostle Thomas. When astrologers predicted that his own son would some day become a Christian, Abenner had the young prince Josaphat isolated from external contact. Despite the imprisonment, Josaphat met the hermit Saint Barlaam and converted to Christianity. Josaphat kept his faith even in the face of his father's anger and persuasion. Eventually Abenner converted, turned over his throne to Josaphat, and retired to the desert to become a hermit. Josaphat himself later abdicated and went into seclusion with his old teacher Barlaam.[2]

Name

Ioasaph (Georgian Iodasaph, Arabic Yūdhasaf or Būdhasaf) is derived from the Sanskrit Bodhisattva.[5][6][15] The Sanskrit word was changed to Bodisav in Persian texts in the 6th or 7th century, then to Budhasaf or Yudasaf in an 8th-century Arabic document (possibly Arabic initial "b" ﺑ changed to "y" ﻳ by duplication of a dot in handwriting).[16] This became Iodasaph in Georgia in the 10th century, and that name was adapted as Ioasaph in Greece in the 11th century, and then was assimilated to Iosaphat/Josaphat in Latin.[17]

Feast day

Although Barlaam and Josaphat were never formally canonized, they were included in earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology (feast day 27 November)[18][19] — though not in the Roman Missal — and in the Eastern Orthodox Church liturgical calendar (26 August in Greek tradition etc.[4] / 19 November in Russian tradition).[7][8]

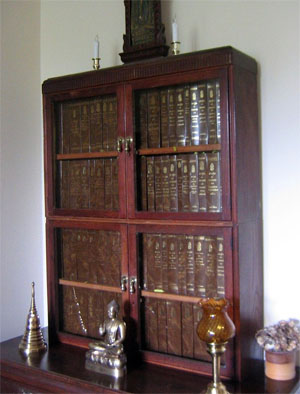

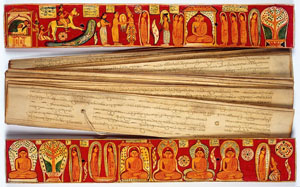

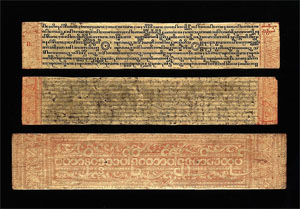

Texts

A page from the 1896 edition by Joseph Jacobs at the University of Toronto (Click on image to read the book)

There are a large number of different books in various languages, all dealing with the lives of Saints Barlaam and Josaphat in India. In this hagiographic tradition, the life and teachings of Josaphat have many parallels with those of the Buddha. "But not till the mid-nineteenth century was it recognised that, in Josaphat, the Buddha had been venerated as a Christian saint for about a thousand years."[20] The authorship of the work is disputed. The origins of the story seem to be a Central Asian manuscript written in the Manichaean tradition. This book was translated into Georgian and Arabic.

Greek manuscripts

The best-known version in Europe comes from a separate, but not wholly independent, source, written in Greek, and, although anonymous, attributed to a monk named John. It was only considerably later that the tradition arose that this was John of Damascus, but most scholars no longer accept this attribution. Instead much evidence points to Euthymius of Athos, a Georgian who died in 1028.[21]

The modern edition of the Greek text, from the 160 surviving variant manuscripts (2006), with introduction (German, 2009) is published as Volume 6 of the works of John the Damascene by the monks of the Abbey of Scheyern, edited by Robert Volk. It was included in the edition due to the traditional ascription, but marked "spuria" as the translator is the Georgian monk Euthymius the Hagiorite (ca. 955–1028) at Mount Athos and not John the Damascene of the monastery of Saint Sabas in the Judaean Desert. The 2009 introduction includes an overview.[22]

English manuscripts

Among the manuscripts in English, two of the most important are the British Museum MS Egerton 876 (the basis for Ikegami's book) and MS Peterhouse 257 (the basis for Hirsh's book) at the University of Cambridge. The book contains a tale similar to The Three Caskets found in the Gesta Romanorum and later in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice.[21]

Editions

Arabic

• E. Rehatsek – The Book of the King's Son and the Ascetic – English translation (1888) based on the Halle Arabic manuscript

• Gimaret – Le livre de Bilawhar et Budasaf – French translation of Bombay Arabic manuscript

Georgian

• David Marshall Lang: The Balavariani: A Tale from the Christian East California University Press: Los Angeles, 1966. Translation of the long version Georgian work that probably served as a basis for the Greek text. Jerusalem MS140

• David Marshall Lang: Wisdom of Balahvar – the short Georgian version Jerusalem MS36, 1960

• The Balavariani (Georgian and Arabic ბალავარიანი, بلوریانی)

Greek

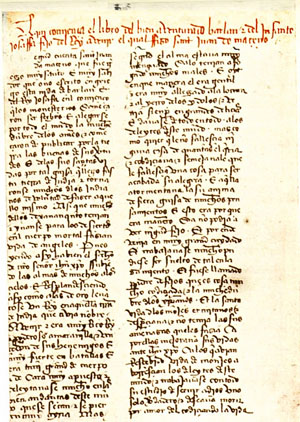

First page of the Barlam and Josephat manuscript at the Biblioteca Nacional de España, 14th or 15th century

• Robert Volk, Die Schriften des Johannes von Damaskos VI/1: Historia animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (spuria). Patristische Texte und Studien Bd. 61. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2009. Pp. xlii, 596. ISBN 978-3-11-019462-3.

• Robert Volk, Die Schriften des Johannes von Damaskos VI/2: Historia animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (spuria). Text und zehn Appendices. Patristische Texte und Studien Bd. 60. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2006. Pp. xiv, 512. ISBN 978-3-11-018134-0.

• Boissonade – older edition of the Greek

• G.R. Woodward and H. Mattingly – older English translation of the Greek Online Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1914

• S. Ioannis Damasceni Historia, de vitis et rebvs gestis SS. Barlaam Eremitae, & Iosaphat Indiæ regis. Iacobo Billio Prunæo, S. Michaëlis in eremo Cœnobiarcha interprete. Coloniae, In Officina Birckmannica, sumptibus Arnoldi Mylij. Anno M. D. XCIII. – Modern Latin translation of the Greek.

• Vitæ et res gestæ SS. Barlaam eremitæ, et Iosaphat Indiæ regis. S. Io. Damasceno avctores, Iac. Billio Prunæo interprete. Antverpiæ, Sumptibus Viduæ & hæredum Ioannis Belleri. 1602. – Modern Latin translation of the Greek.

• S. Ioannis Damasceni Historia, de vitis et rebvs gestis SS. Barlaam Eremitæ, & Iosaphat Indiæ regis. Iacobo Billio Prvnæo, S. Michaëlis in eremo Cœnobiarcha, interprete. Nune denuò accuratissimè à P. Societate Iesv revisa & correcta. Coloniæ Agrippinæ, Apud Iodocvm Kalcoven, M. DC. XLIII. – Modern Latin translation of the Greek.

Latin

• Codex VIII B10, Naples

Ethiopic

• Baralâm and Yĕwâsĕf. Budge, E.A. Wallis. Baralam and Yewasef : the Ethiopic version of a Christianized recension of the Buddhist legend of the Buddha and the Bodhisattva. Published: London; New York: Kegan Paul; Biggleswade, UK: Distributed by Extenza-Turpin Distribution; New York: Distributed by Columbia University Press, 2004.

Old French

• Jean Sonet, Le roman de Barlaam et Josaphat (Namur, 1949–52) after Tours MS949

• Leonard Mills, after Vatican MS660

• Zotenberg and Meyer, after Gui de Cambrai MS1153

Catalan

• Gerhard Moldenhauer Vida de Barlan MS174

Provencal

• Ferdinand Heuckenkamp, version in langue d'Oc

• Jeanroy, Provençal version, after Heuckenkamp

• Nelli, Troubadours, after Heuckenkamp

• Occitan, BN1049

Italian

• G.B. Bottari, edition of various old Italian MS.

• Georg Maas, old Italian MS3383

Portuguese

• Hilário da Lourinhã. Vida do honorado Infante Josaphate, filho del Rey Avenir, versão de frei Hilário da Lourinhã: e a identificação, por Diogo do Couto (1542–1616), de Josaphate com o Buda. Introduction and notes by Margarida Corrêa de Lacerda. Lisboa: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1963.

Serbian

• "Barlaam and Josaphat" in the Eastern Orthodox version comes from John of Damascus, copied and translated into Old Church Slavonic by anonymous monk-scribes from the 9th-11th centuries, and in modern Serbian by Ava Justin Popović ("Lives of the Saints" for November, pp. 563-590), an abridged version of which is given in the Ohrid Prologue of Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović.

English

• Hirsh, John C. (editor). Barlam and Iosaphat: a Middle English life of Buddha. Edited from MS Peterhouse 257. London; New York: Published for the Early English Text Society by the Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-19-722292-7

• Ikegami, Keiko. Barlaam and Josaphat : a transcription of MS Egerton 876 with notes, glossary, and comparative study of the Middle English and Japanese versions, New York: AMS Press, 1999. ISBN 0-404-64161-X

• John Damascene, Barlaam and Ioasaph (Loeb Classical Library). David M. Lang (introduction), G. R. Woodward (translator), Harold Mattingly (translator)• Publisher: Loeb Classical Library, W. Heinemann; 1967, 1914. ISBN 0-674-99038-2

• MacDonald, K.S. (editor). The story of Barlaam and Joasaph : Buddhism & Christianity. With philological introduction and notes to the Vernon, Harleian and Bodleian versions, by John Morrison. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1895.

Old Norse

Further information: Barlaams saga ok Jósafats

• Magnus Rindal (editor). Barlaams ok Josaphats saga. Oslo: Published for Kjeldeskriftfondet by Norsk historisk kjeldeskrift-insitutt, 1981. ISBN 82-7061-275-8

• Keyser, R.; Unger, C. R. (1851). Barlaams ok Josaphats saga: En religiös romantisk fortælling om Barlaam og Josaphat. Christiania.

Tibetan

• Rgya Tch'er Rol Pa – ou: Développement des jeux, Philippe Édouard Foucaux (1811–1894) 1847. Lalitavistara

Hebrew

• Avraham ben Shmuel ha-Levi Ibn Hasdai, Ben hammelekh vehannazir (13th century)

• Habermann, Avraham Meir (ed.), Avraham ben Hasdai, Ben hammelekh vehannazir, Jerusalem: Mahberot lesifrut – Mossad haRav Kook 1950 (in Hebrew).

• Abraham ben Shemuel Halevi ibn Hasdai, Ben hamelekh vehanazir, Ed. by Ayelet Oettinger, Universitat Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv 2011 (in Hebrew).

See also

• Gautama Buddha in world religions

• Thomas the Apostle

• Buddhism and Christianity

• Josaphat (disambiguation)

• Barlaams saga ok Jósafats

• Greco-Buddhism

• Life is a Dream, Spanish play incorporating the theme of the imprisoned prince

Notes and references

1. John Walbridge The Wisdom of the Mystic East: Suhrawardī and Platonic Orientalism Page 129 – 2001 "The form Būdhīsaf is the original, as shown by Sogdian form Pwtysfi and the early New Persian form Bwdysf. ... On the Christian versions see A. S. Geden, Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, s.v. "Josaphat, Barlaam and," and M. P. Alfaric, ..."

2. The Golden Legend: The Story of Barlaam and Josaphat Archived 16 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

3. Wilson, Joseph (2009). "The Life of the Saint and the Animal: Asian Religious Influence in the Medieval Christian West". The Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture. 3 (2): 169–194. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v3i2.169. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

4. Great Synaxaristes (in Greek): Ὁ Ὅσιος Ἰωάσαφ γιὸς τοῦ βασιλιὰ τῆς Ἰνδίας Ἄβενιρ. 26 Αυγούστου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

5. Macdonnel, Arthur Anthony (1900). " Sanskrit Literature and the West.". A History of Sanskrit Literature. New York: D. Appleton and Co. p. 420.

6. Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Barlaam and Josaphat" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

7. November 19/December 2 Archived 1 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Orthodox Calendar (Pravoslavie.ru).

8. Venerable Joasaph the Prince of India. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

9. "St. Euthymius of Athos the translator", Orthodox Church in America

10. William Cantwell Smith, "Towards a World Theology" (1981)

11. F.C. Conybeare, "The Barlaam and Josaphat Legend in the Ancient Georgian and Armenian Literatures" (Gorgias Press)

12. Sangharakshita, "From Genesis to the Diamond Sutra – A Western Buddhist's Encounters with Christianity" (Windhorse Publications, 2005), p.165

13. Die Blüte der heiligen Dichtkunst im deutschen Mittelalter ist vielleicht »Barlaam und Josaphat«... See Heinrich Heine, Die romantische Schule (Erstes Buch) at heinrich-heine.net. (in German).

14. Cañizares Ferriz, Patricia (1 January 2000). "La Historia de los dos soldados de Cristo, Barlaan y Josafat, traducida por Juan de Arce Solorzeno (Madrid 1608)" (PDF). Cuadernos de Filología Clásica. Estudios Latinos (in Spanish). 19: 260. ISSN 1988-2343. Retrieved 21 February 2021. y que ya en el s. XVI se convirtiera en un arma defensora de la validez de la vida monástica y del libre albedrío frente a la doctrina luterana. [and that, already in the 16th century, it would become a weapon defending the validity of monastic life and free will} against Lutheran doctrine.]

15. Kevin Trainor (ed), "Buddhism" (Duncan Baird Publishers, 2001), p. 24

16. Emmanuel Choisnel Les Parthes et la Route de la soie 2004 Page 202 "Le nom de Josaphat dérive, tout comme son associé Barlaam dans la légende, du mot Bodhisattva. Le terme Bodhisattva passa d'abord en pehlevi, puis en arabe, où il devint Budasaf. Étant donné qu'en arabe le "b" et le "y" ne different que ..."

17. D.M. Lang, The Life of the Blessed Iodasaph: A New Oriental Christian Version of the Barlaam and Ioasaph Romance (Jerusalem, Greek Patriarchal Library: Georgian MS 140), BSOAS 20.1/3 (1957):

18. Martyrologium Romanum 27 Novembris Apud Indos, Persis finitimos, sanctorum Barlaam et Josaphat, quorum actus mirandos sanctus Joannes Damascenus conscripsit.

19. Emmanuel Choisnel Les Parthes et la Route de la soie 2004 – Page 202 "Dans l'Église grecque orthodoxe, Saint Josaphat a été fêté le 26 août et, dans l'Église romaine, le 27 novembre a été la ... D. M. Lang, auteur du chapitre « Iran, Armenia and Georgia » dans la Cambridge History of Iran, estime pour sa part ..."

20. Barlaam and Ioasaph, John Damascene, Loeb Classical Library 34, Introduction by David M. Lang

21. Barlaam and Ioasaph, John Damascene, Loeb Classical Library 34, at LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY

22. Pieter W. van der Horst, Utrecht – Review of 2006/2009 Robert Volk edition

External links

• Asmussen, J. P. (1988). "BARLAAM AND IOSAPH". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 8. p. 801.

• Barlaam and Ioasaph (Legend in form attributed to St John of Damascus)

• "Barlaam and Josaphat" . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

• Barlaam and Josaphat in Jewish Encyclopedia

• Barlaam et Josaphat. Augsburg, Günther Zainer, ca. 1476. From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

• "Barlaam and Josaphat" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.