by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/13/21

The identification of Raja Priyadarsin with Raja Asoka was based entirely upon Ceylonese Buddhist chronicles. Talboys Wheeler wrote in 1874, "The identification of Raja Priyadarsin of the Edicts with Raja Asoka of the Buddhist chronicles was first pointed out by Mr. Turnour who rested it upon a passage in the Dipavamsa. The late Prof. [Horace Hayman] Wilson objected to this identification."1 [History of India, Hindu, Buddhist and Brahmanical, 280.] Prof. Rhys Davids declared, "It is not too much to say that without the help of the Ceylon Books, the striking identification of the King Piyadassi of the edicts with the king Asoka of history would never have been made."2 [Buddhist India, 273.] But the Ceylon chronicles are admitted to be utterly worthless as history, and according to Wheeler, "the Buddhist chronicles might be dismissed as a monkish jumble of myths and names,3 [EHI, 171] and even Vincent Smith in the preface to his Asoka himself said, "I reject absolutely the Ceylonese chronology...... The undeserved credit given to the monks of Ceylon has been a great hindrance to the right understanding of ancient Indian history." And yet it is on such undeserved credit that the identity of Priyadarsin with Asoka Maurya rests to this day.

-- History of Classical Sanskrit Literature, by Kavyavinoda, Sahityaratnakara M. Krishnamachariar, M.A., M.I., Ph.D., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of London (Of the Madras Judicial Service), Assisted by His Son M. Srinivasachariar, B.A., B.L., Advocate, Madras, 1937

Highlights:

The contents of the Mahavamsa can be broadly divided into four categories:[2]

The Buddha's Visits to Sri Lanka: This material recounts three legendary visits by the Buddha to the island of Sri Lanka. These stories describe the Buddha subduing or driving away the Yakkhas (Yakshas) and Nagas that were inhabiting the island and delivering a prophecy that Sri Lanka will become an important Buddhist center. These visits are not mentioned in the Pali Canon or other early sources….

Genealogies and lineages of kings of Sri Lanka... This material may have been derived from earlier royal chronicles and king lists that were recorded orally in vernacular languages…

History of the Buddhist Sangha: This section of the Mahavamsa deals with the mission sent by Emperor Ashoka to Sri Lanka, the transplantation of the bodhi tree, and the founding of the Mahavihara. It includes the names of prominent monks and nuns in the early Sri Lankan sangha. It also includes accounts of the early Buddhist councils and the first recording of the Pali canon in writing….

Chronicles of Sri Lanka…

Authorship of the Mahavamsa is attributed to a monk called Mahānāma by the Mahavamsa-tika. Mahānāma is described as residing in a monastery belonging to general Dighasanda and affiliated with the Mahavihara…

A companion volume, the Culavamsa "Lesser Chronicle", compiled by Sinhala monks, covers the period from the 4th century to the British takeover of Sri Lanka in 1815. The Culavamsa was compiled by a number of authors of different time periods…

The combined work, [is] sometimes referred to collectively as the Mahavamsa…

It is very important in dating the consecration of the Maurya Emperor Ashoka…

The Mahavamsa first came to the attention of Western readers around 1809 CE, when Sir Alexander Johnston, Chief Justice of the British colony in Ceylon, sent manuscripts of it and other Sri Lankan chronicles to Europe for publication. Eugène Burnouf produced a Romanized transliteration and translation into Latin in 1826... Working from Johnston's manuscripts, Edward Upham published an English translation in 1833, but it was marked by a number of errors in translation and interpretation, among them suggesting that the Buddha was born in Sri Lanka and built a monastery atop Adam's Peak. The first printed edition and widely read English translation was published in 1837 by George Turnour, an historian and officer of the Ceylon Civil Service…

Historiographical sources are rare in much of South Asia…

The Mahavamsa has, especially in modern Sri Lanka, acquired a significance as a document with a political message. The Sinhalese majority often use Manavamsa as a proof of their claim that Sri Lanka is a Buddhist nation from historical time…

Early Western scholars like Otto Franke dismissed the possibility that the Mahavamsa contained reliable historical content…

Wilhelm Geiger was one of the first Western scholars to suggest that it was possible to separate useful historical information from the mythic and poetic elaborations of the chronicle…. Geiger hypothesized that the Mahavamsa had been based on earlier Sinhala sources that originated on the island of Ceylon. While Geiger did not believe that the details provided with every story and name were reliable, he broke from earlier scholars in believing that the Mahavamsa faithfully reflected an earlier tradition that had preserved the names and deeds of various royal and religious leaders, rather than being a pure work of heroic literary fiction. He regarded the early chapters of the Culavamsa as the most accurate, with the early chapters of the Mahavamsa being too remote historically and the later sections of the Culavamsa marked by excessive elaboration.

Geiger's Sinhala student G. C. Mendis was more openly skeptical about certain portions of the text, specifically citing the story of the Sinhala ancestor Vijaya as being too remote historically from its source and too similar to an epic poem or other literary creation to be seriously regarded as history. The date of Vijaya's arrival is thought to have been artificially fixed to coincide with the date for the death of Gautama Buddha around 543 BCE. The Chinese pilgrims Fa Hsien and Hsuan Tsang both recorded myths of the origins of the Sinhala people in their travels that varied significantly from the versions recorded in the Mahavamsa…

The story of the Buddha's three visits to Sri Lanka are not recorded in any source outside of the Mahavamsa tradition. Moreover, the genealogy of the Buddha recorded in the Mahavamsa describes him as being the product of four cross cousin marriages. Cross-cousin marriage is associated historically with the Dravidian people of southern India -- both Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhala practiced cross-cousin marriage historically -- but exogamous marriage was the norm in the regions of northern India associated with the life of the Buddha. No mention of cross-cousin marriage is found in earlier Buddhist sources…

The historical accuracy of Mahinda converting the Sri Lankan king to Buddhism is also debated. Hermann Oldenberg, a German scholar of Indology who has published studies on the Buddha and translated many Pali texts, considers this story a "pure invention". V. A. Smith (Author of Ashoka and Early history of India) also refers to this story as "a tissue of absurdities". V. A. Smith and Professor Hermann came to this conclusion due to Ashoka not mentioning the handing over of his son, Mahinda, to the temple to become a Buddhist missionary and Mahinda's role in converting the Sri Lankan king to Buddhism, in his 13th year Rock Edicts, particularly Rock-Edict XIII. Sources outside of Sri Lanka and the Mahavamsa tradition do not mention Mahinda as Ashoka's son….

The Mahavamsa is believed to have originated from an earlier chronicle known as the Dipavamsa... The Dipavamsa is much simpler and contains less information than the Mahavamsa and probably served as the nucleus of an oral tradition that was eventually incorporated into the written Mahavamsa.Regarding the Vijaya legend, Dipavamsa has tried to be less super-natural than the later work, Mahavamsa in referring to the husband of the Kalinga-Vanga princess, ancestor of Vijya, as a man named Sinha who was an outlaw that attacked caravans en route. In the meantime, Sinha-bahu and Sinhasivali, as king and queen of the kingdom of Lala (Lata), "gave birth to twin sons, sixteen times." The eldest was Vijaya and the second was Sumitta. As Vijaya was of cruel and unseemly conduct, the enraged people requested the king to kill his son. But the king caused him and his seven hundred followers to leave the kingdom, and they landed in Sri Lanka, at a place called Tamba-panni, on the exact day when the Buddha passed into Maha Parinibbana.

-- Dipavamsa, by Wikipedia

The Dipavamsa is believed to have been the first Pali text composed entirely in Ceylon.

A subsequent work sometimes known as Culavamsa extends the Mahavamsa to cover the period from the reign of Mahasena of Anuradhapura (277–304 CE) until 1815, when the entire island was surrendered to the British throne. The Culavamsa contains three sections composed by five different authors (one anonymous) belonging to successive historical periods….

A commentary on the Mahavamsa, known as the Mahavamsa-tika, is believed to have been composed before the first additions composing the Culavamsa were written… This commentary provides explanations of ambiguous Pali terms used in the Mahavamsa, and in some cases adds additional details or clarifies differences between different versions of the Mahavamsa…

-- Mahavamsa, by Wikipedia

The identification of Raja Priyadarsin with Raja Asoka was based entirely upon Ceylonese Buddhist chronicles. Talboys Wheeler wrote in 1874, "The identification of Raja Priyadarsin of the Edicts with Raja Asoka of the Buddhist chronicles was first pointed out by Mr. Turnour who rested it upon a passage in the Dipavamsa. The late Prof. [Horace Hayman] Wilson objected to this identification."1 [History of India, Hindu, Buddhist and Brahmanical, 280.] Prof. Rhys Davids declared, "It is not too much to say that without the help of the Ceylon Books, the striking identification of the King Piyadassi of the edicts with the king Asoka of history would never have been made."2 [Buddhist India, 273.] But the Ceylon chronicles are admitted to be utterly worthless as history, and according to Wheeler, "the Buddhist chronicles might be dismissed as a monkish jumble of myths and names,3 [EHI, 171] and even Vincent Smith in the preface to his Asoka himself said, "I reject absolutely the Ceylonese chronology...... The undeserved credit given to the monks of Ceylon has been a great hindrance to the right understanding of ancient Indian history." And yet it is on such undeserved credit that the identity of Priyadarsin with Asoka Maurya rests to this day.

-- History of Classical Sanskrit Literature, by Kavyavinoda, Sahityaratnakara M. Krishnamachariar, M.A., M.I., Ph.D., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of London (Of the Madras Judicial Service), Assisted by His Son M. Srinivasachariar, B.A., B.L., Advocate, Madras, 1937

Mahāvaṃsa

Type: Post-canonical text; Chronicle

Composition: 5th Century CE

Attribution: Mahānāma

Commentary: Mahavamsa-tika

PTS Abbreviation: Bv

Pāli literature

The Mahavamsa ("Great Chronicle", Pali Mahāvaṃsa) (5th century CE) is the meticulously kept historical chronicle of Sri Lanka written in the style of an epic poem written in the Pali language.[1] It relates the history of Sri Lanka from its legendary beginnings up to the reign of Mahasena of Anuradhapura (A.D. 302) covering the period between the arrival of Prince Vijaya from India in 543 BCE to his reign (277–304 CE) and later updated by different writers. It was composed by a Buddhist monk at the Mahavihara temple in Anuradhapura about the fifth century A.D.

Prince Vijaya (Sinhala: විජය කුමරු) was the traditional first Sinhalese king of Sri Lanka, mentioned in the Pali chronicles, including Mahavamsa. According to these chronicles, he is the first recorded King of Sri Lanka. His reign is traditionally dated to 543–505 BCE. According to the legends, he and several hundred of his followers came to Lanka after being expelled from an Indian kingdom. According to Mahavamsa, in Lanka, they defeated a Yakkha colony near to "Thammena" (Thambapanni) and displaced the island's original inhabitants (Yakkhas), from their city of "Sirisavatthu" with the support of princess Kuveni and established a kingdom and became ancestors of the modern Sinhalese people.

-- Prince Vijaya, by Wikipedia

Contents

The contents of the Mahavamsa can be broadly divided into four categories:[2]

• The Buddha's Visits to Sri Lanka: This material recounts three legendary visits by the Buddha to the island of Sri Lanka. These stories describe the Buddha subduing or driving away the Yakkhas (Yakshas) and Nagas that were inhabiting the island and delivering a prophecy that Sri Lanka will become an important Buddhist center. These visits are not mentioned in the Pali Canon or other early sources.

• Chronicles of Kings of Sri Lanka: This material consists of genealogies and lineages of kings of Sri Lanka, sometimes with stories about their succession or notable incidents in their reigns. This material may have been derived from earlier royal chronicles and king lists that were recorded orally in vernacular languages, and are a significant source of material about the history of Sri Lanka and nearby Indian kingdoms.

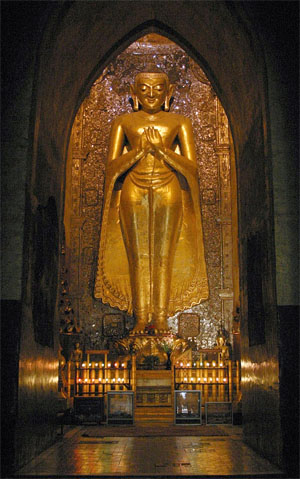

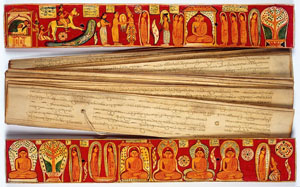

• History of the Buddhist Sangha: This section of the Mahavamsa deals with the mission sent by Emperor Ashoka to Sri Lanka, the transplantation of the bodhi tree, and the founding of the Mahavihara. It includes the names of prominent monks and nuns in the early Sri Lankan sangha. It also includes accounts of the early Buddhist councils and the first recording of the Pali canon in writing. This is a significant source of material about the development of the early Buddhist community, and includes the names of missionaries dispatched to various regions of South and Southeast Asia, some of which have been confirmed by inscriptions and other archaeological evidence.

• Chronicles of Sri Lanka: This material begins with the immigration of Prince Vijaya from India with his retinue and continues until the reign of King Mahasena, recounting wars, succession disputes, building of stupas and reliquaries, and other notable incidents. An extensive chronicle of the war between the Sinhala King Dutthagamani and Tamil invader, and later king, Elara (861 verses in the Mahavamsa compared with 13 verses in the Dipavamsa) may represent the incorporation of a popular epic from the vernacular tradition.[2]

While much of the contents of the Mahavamsa is derived from expansions of the material found in the Dipavamsa, several passages specifically dealing with the Abhayagiri vihara are omitted, suggesting that the Mahavamsa was more specifically associated with the Mahavihara.[2]

History

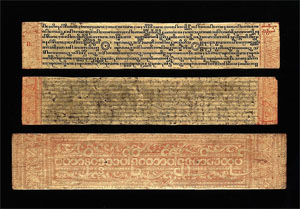

Buddhist monks of the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya maintained chronicles of Sri Lankan history starting from the third century BCE. These annals were combined and compiled into a single document in the 5th Century while Dhatusena of Anuradhapura was ruling the Anuradhapura Kingdom. It was written based on prior ancient compilations known as the Atthakatha (sometimes Sinhalaatthakatha), which were commentaries written in Sinhala.[3] An earlier document known as the Dipavamsa (4th century CE) "Island Chronicles" is much simpler and contains less information than the Mahavamsa and was probably compiled using the Atthakatha on the Mahavamsa as well.

Authorship of the Mahavamsa is attributed to a monk called Mahānāma by the Mahavamsa-tika (see #Related Works). Mahānāma is described as residing in a monastery belonging to general Dighasanda and affiliated with the Mahavihara, but no other reliable biographical information is known.[2]

The commentator of the Mahavamsa says that Dighasanda was a nickname of a certain general of King Devanampiya Tissa and that he built the monastery known after his name.

-- Mahanama in the Pali Literature, by R. Siddhartha, The Indian Historical Quarterly

Mahānāma introduces the Mahavamsa with a passage that claims that his intention is to correct repetitions and shortcomings that afflicted the chronicle compiled by the ancients- this may refer either to the Dipavamsa or to the Sinhala Atthakatha.[2]

A companion volume, the Culavamsa "Lesser Chronicle", compiled by Sinhala monks, covers the period from the 4th century to the British takeover of Sri Lanka in 1815. The Culavamsa was compiled by a number of authors of different time periods.

The combined work, sometimes referred to collectively as the Mahavamsa, provides a continuous historical record of over two millennia, and is considered one of the world's longest unbroken historical accounts.[4] It is one of the few documents containing material relating to the Nāga and Yakkha peoples, indigenous inhabitants of Lanka prior to the legendary arrival of Prince Vijaya from Singha Pura of Kalinga.

As it often refers to the royal dynasties of India, the Mahavamsa is also valuable for historians who wish to date and relate contemporary royal dynasties in the Indian subcontinent. It is very important in dating the consecration of the Maurya Emperor Ashoka, which is related to the synchronicity with the Seleucid Empire and Alexander the Great.

Indian excavations in Sanchi and other locations, confirm the Mahavamsa account of the empire of Ashoka. The accounts given in the Mahavamsa are also amply supported by the numerous stone inscriptions, mostly in Sinhala, found in Sri Lanka.[5] K. Indrapala [6] has also upheld the historical value of the Mahavamsa. If not for the Mahavamsa, the story behind the large stupas in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, such as Ruwanwelisaya, Jetavanaramaya, Abhayagiri vihāra and other works of ancient engineering would never have been known.

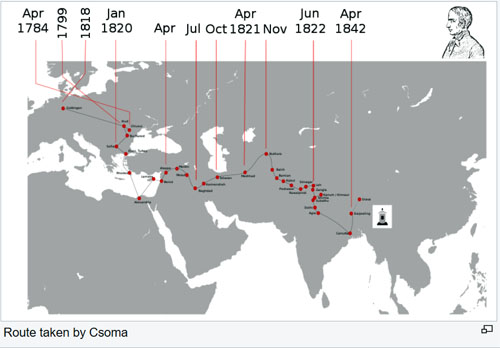

The Mahavamsa first came to the attention of Western readers around 1809 CE, when Sir Alexander Johnston, Chief Justice of the British colony in Ceylon, sent manuscripts of it and other Sri Lankan chronicles to Europe for publication.[7] Eugène Burnouf produced a Romanized transliteration and translation into Latin in 1826, but these garnered relatively little attention.[8]:86 Working from Johnston's manuscripts, Edward Upham published an English translation in 1833, but it was marked by a number of errors in translation and interpretation, among them suggesting that the Buddha was born in Sri Lanka and built a monastery atop Adam's Peak.[8]:86 The first printed edition and widely read English translation was published in 1837 by George Turnour, an historian and officer of the Ceylon Civil Service.[8]:86

NOTE 2.—The general correctness with which Marco has here related the legendary history of Sakya's devotion to an ascetic life, as the preliminary to his becoming the Buddha or Divinely Perfect Being, shows what a strong impression the tale had made upon him. He is, of course, wrong in placing the scene of the history in Ceylon, though probably it was so told him, as the vulgar in all Buddhist countries do seem to localise the legends in regions known to them.

Sakya Sinha, Sakya Muni, or Gautama, originally called Siddhárta, was the son of Súddhodhana, the Kshatriya prince of Kapilavastu, a small state north of the Ganges, near the borders of Oudh...

-- The Travels of Marco Polo, by Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa

A German translation of Mahavamsa was completed by Wilhelm Geiger in 1912. This was then translated into English by Mabel Haynes Bode, and revised by Geiger.[9]

Wilhelm Ludwig Geiger (21 July 1856 to 2 September 1943) was a German orientalist in the fields of Indo-Iranian languages and the history of Iran and Sri Lanka. He was known as a specialist in Pali, Sinhala language and the Dhivehi language of the Maldives. He is especially known for his work on the Sri Lankan chronicles Mahāvaṃsa and Cūlavaṃsa of which he made critical editions of the Pali text and English translations with the help of assistant translators.

He was born in Nuremberg, the son of an evangelical clergyman, and was educated especially at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg under the Iranian scholar Friedrich von Spiegel. During his studies, he joined the fraternity Uttenruthia. After completing his Ph.D. thesis in 1878, he became a lecturer on ancient Iranian and Indian philology and then a master at a gymnasium . In 1891 he was offered a chair in Indo-European Comparative Philology at the University of Erlangen, succeeding Spiegel. His first published works were on ancient Iranian history, archeology and philology.

He traveled to Ceylon in 1895 to study the language. [2] [3]

He died in Neubiberg.

Among his children were the physicist Hans Geiger, inventor of the Geiger counter, and the meteorologist Rudolf Geiger.

-- Wilhelm Geiger, by Wikipedia

Historical and literary significance

Historiographical sources are rare in much of South Asia. As a result of the Mahavamsa, comparatively more is known about the history of the island of Ceylon and neighboring regions than that of most of the subcontinent. Its contents have aided in the identification and corroboration of archaeological sites and inscriptions associated with early Buddhism, the empire of Ashoka, and the Tamil kingdoms of southern India.[2]

The Mahamvasa covers the early history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, beginning with the time of Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism. It also briefly recounts the history of Buddhism in India, from the date of the Buddha's death to the 3rd Buddhist council where the Dharma was reviewed. Every chapter of the Mahavamsa ends by stating that it is written for the "serene joy of the pious". From the emphasis of its point-of-view, and being compiled to record the good deeds of the kings who were patrons of the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya,[10] it has been said to support Sinhalese nationalism.[11][12]

Besides being an important historical source, the Mahavamsa is the most important epic poem in the Pali language. Its stories of battles and invasions, court intrigue, great constructions of stupas and water reservoirs, written in elegant verse suitable for memorization, caught the imagination of the Buddhist world of the time. Unlike many texts written in antiquity, it also discusses various aspects of the lives of ordinary people, how they joined the King's army or farmed. Thus the Mahavamsa was taken along the Silk Road to many Buddhist lands.[13] Parts of it were translated, retold, and absorbed into other languages. An extended version of the Mahavamsa, which gives many more details, has also been found in Southeast Asia.[14][2] The Mahavamsa gave rise to many other Pali chronicles, making Sri Lanka of that period probably the world's leading center in Pali literature.

Political significance

The Mahavamsa has, especially in modern Sri Lanka, acquired a significance as a document with a political message.[15] The Sinhalese majority often use Manavamsa as a proof of their claim that Sri Lanka is a Buddhist nation from historical time. The British historian Jane Russell[16] has recounted how a process of "Mahavamsa bashing" began in the 1930s, especially from within the Tamil Nationalist movement. The Mahavamsa, being a history of the Sinhala Buddhists, presented itself to the Tamil Nationalists and the Sinhala Nationalists as the hegemonic epic of the Sinhala people. This view was attacked by G. G. Ponnambalam, the leader of the Nationalist Tamils in the 1930s. He claimed that most of the Sinhala kings, including Vijaya, Kasyapa, and Parakramabahu, were Tamils. Ponnambalam's 1939 speech in Nawalapitiya, attacking the claim that Sri Lanka is a Sinhalese, Buddhist nation was seen as an act against the notion of creating a Buddhist only nation. The Sinhala majority responded with a mob riot, which engulfed Nawalapitiya, Passara, Maskeliya, and even Jaffna.[16]:148[17] The riots were rapidly put down by the British colonial government, but later this turned through various movements into the civil war in Sri Lanka which ended in 2009.

Historical accuracy

Early Western scholars like Otto Franke dismissed the possibility that the Mahavamsa contained reliable historical content, but subsequent evidence from inscriptions and archaeological finds have confirmed that there is a factual basis for many of the stories recorded in the Mahavamsa, including Ashoka's missionary work and the kings associated with founding various monasteries and stupas.[8]:47,90

Questions of authorship

According to some scholars such as Christopher I. Beckwith, Ashoka, whose name only appears in the Minor Rock Edicts, should be differentiated from the ruler Piyadasi, or Devanampiya Piyadasi (i.e. "Beloved of the Gods Piyadasi", "Beloved of the Gods" being a fairly widespread title for "King"), who is named as the author of the Major Pillar Edicts and the Major Rock Edicts. Beckwith also highlights the fact that [neither] Buddhism nor the Buddha are mentioned in the Major Edicts, but only in the Minor Edicts. Further, the Buddhist notions described in the Minor Edicts (such as the Buddhist canonical writings in Minor Edict No.3 at Bairat, the mention of a Buddha of the past Kanakamuni Buddha in the Nigali Sagar Minor Pillar Edict) are more characteristic of the "Normative Buddhism" of the Saka-Kushan period around the 2nd century CE.

This inscriptional evidence may suggest that Piyadasi and Ashoka were two different rulers. According to Beckwith, Piyadasi was living in the 3rd century BCE, probably the son of Chandragupta Maurya known to the Greeks as Amitrochates, and only advocating for piety ("Dharma") in his Major Pillar Edicts and Major Rock Edicts, without ever mentioning Buddhism, the Buddha or the Samgha. Since he does mention a pilgrimage to Sambhodi (Bodh Gaya, in Major Rock Edict No.8) however, he may have adhered to an "early, pietistic, popular" form of Buddhism. Also, the geographical spread of his inscription shows that Piyadasi ruled a vast Empire, contiguous with the Seleucid Empire in the West.

On the contrary, for Beckwith, Ashoka himself was a later king of the 1st-2nd century CE, whose name only appears explicitly in the Minor Rock Edicts and allusively in the Minor Pillar Edicts, and who does mention the Buddha and the Samgha, explicitly promoting Buddhism. He may have been an unknown or possibly invented ruler named Devanampriya Asoka, with the intent of propagating a later, more institutional version of the Buddhist faith. His inscriptions cover a very different and much smaller geographical area, clustering in Central India. According to Beckwith, the inscriptions of this later Ashoka were typical of the later forms of "normative Buddhism", which are well attested from inscriptions and Gandhari manuscripts dated to the turn of the millennium, and around the time of the Kushan Empire. The quality of the inscriptions of this Ashoka is significantly lower than the quality of the inscriptions of the earlier Piyadasi.

-- Edicts of Ashoka, by Wikipedia

Wilhelm Geiger was one of the first Western scholars to suggest that it was possible to separate useful historical information from the mythic and poetic elaborations of the chronicle. While other scholars had assumed that the Mahavamsa had been assembled from borrowed material from Indian Pali sources, Geiger hypothesized that the Mahavamsa had been based on earlier Sinhala sources that originated on the island of Ceylon. While Geiger did not believe that the details provided with every story and name were reliable, he broke from earlier scholars in believing that the Mahavamsa faithfully reflected an earlier tradition that had preserved the names and deeds of various royal and religious leaders, rather than being a pure work of heroic literary fiction. He regarded the early chapters of the Culavamsa as the most accurate, with the early chapters of the Mahavamsa being too remote historically and the later sections of the Culavamsa marked by excessive elaboration.[8]:90–92

Geiger's Sinhala student G. C. Mendis was more openly skeptical about certain portions of the text, specifically citing the story of the Sinhala ancestor Vijaya as being too remote historically from its source and too similar to an epic poem or other literary creation to be seriously regarded as history.[8]:94 The date of Vijaya's arrival is thought to have been artificially fixed to coincide with the date for the death of Gautama Buddha around 543 BCE.[18][19] The Chinese pilgrims Fa Hsien and Hsuan Tsang both recorded myths of the origins of the Sinhala people in their travels that varied significantly from the versions recorded in the Mahavamsa -- in one version, the Sinhala are descended from naga or nature spirits who traded with Indian merchants, and in another the Sinhala progenitor is a prince exiled for patricide who then slays a wealthy merchant and adopts his 500 children.[8]:58–9

The story of the Buddha's three visits to Sri Lanka are not recorded in any source outside of the Mahavamsa tradition.[8]:48 Moreover, the genealogy of the Buddha recorded in the Mahavamsa describes him as being the product of four cross cousin marriages. Cross-cousin marriage is associated historically with the Dravidian people of southern India -- both Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhala practiced cross-cousin marriage historically -- but exogamous marriage was the norm in the regions of northern India associated with the life of the Buddha.[20] No mention of cross-cousin marriage is found in earlier Buddhist sources, and scholars suspect that this genealogy was created in order to fit the Buddha into conventional Sri Lankan social structures for noble families.[8]:48–9[20]

The historical accuracy of Mahinda converting the Sri Lankan king to Buddhism is also debated. Hermann Oldenberg, a German scholar of Indology who has published studies on the Buddha and translated many Pali texts, considers this story a "pure invention". V. A. Smith (Author of Ashoka and Early history of India) also refers to this story as "a tissue of absurdities". V. A. Smith and Professor Hermann came to this conclusion due to Ashoka not mentioning the handing over of his son, Mahinda, to the temple to become a Buddhist missionary and Mahinda's role in converting the Sri Lankan king to Buddhism, in his 13th year Rock Edicts, particularly Rock-Edict XIII.[21] Sources outside of Sri Lanka and the Mahavamsa tradition do not mention Mahinda as Ashoka's son.[8]

There is also an inconsistency with the year on which Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to Sri Lanka. According to the Mahavamsa, the missionaries arrived in 255 BCE, but according to Edict 13, it was five years earlier in 260 BCE.[21]

Related works

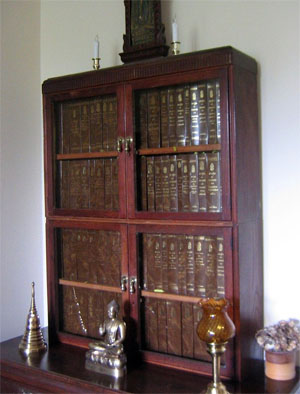

The Mahavamsa is believed to have originated from an earlier chronicle known as the Dipavamsa (4th century CE) ("Island Chronicles"). The Dipavamsa is much simpler and contains less information than the Mahavamsa and probably served as the nucleus of an oral tradition that was eventually incorporated into the written Mahavamsa. The Dipavamsa is believed to have been the first Pali text composed entirely in Ceylon.[2]

A subsequent work sometimes known as Culavamsa extends the Mahavamsa to cover the period from the reign of Mahasena of Anuradhapura (277–304 CE) until 1815, when the entire island was surrendered to the British throne. The Culavamsa contains three sections composed by five different authors (one anonymous) belonging to successive historical periods.[2]

In 1935, Buddhist monk Yagirala Pannananda published Mahavamsa Part III, a Sinhala language continuation of the Mahavamsa that covers the period from the end of the Culavamsa up until 1935.[8]:95–104 While not authorized or supported by any government or religious organization, this continuation of the Mahavamsa was later recognized by the government of Sri Lankan Prime Minister JR Jayawardene.

A commentary on the Mahavamsa, known as the Mahavamsa-tika, is believed to have been composed before the first additions composing the Culavamsa were written, likely some time between AD 1000 and AD 1250. This commentary provides explanations of ambiguous Pali terms used in the Mahavamsa, and in some cases adds additional details or clarifies differences between different versions of the Mahavamsa. Unlike the Mahavamsa itself, which is composed almost entirely from material associated with the Mahavihara, the Mahavamsa-tika makes several references to commentaries and alternate versions of the chronicle associated with the Abhayagiri vihara tradition.[2]

In Southeast Asia, a Pali work referred to as the 'Extended Mahavamsa' includes not only the text of the Sri Lankan Mahavamsa, but also elements of the Thupavamsa, Buddhavamsa, Mahavamsa commentaries, and quotations from various jatakas.[14][2] It is sometimes referred to in academic literature as the 'Kambodian Mahavamsa' or 'Khmer Mahavamsa' because it is distinguished by being recorded in the Khmer script. Its composition is attributed to an otherwise unknown monk called Moggallana and its exact date of composition and origin are unknown, but suspected to be Burma or Thailand.[2]

See also

• History of Sri Lanka

• Anuradhapura

References

1. Sailendra Nath Sen (1 January 1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 91. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

2. Von Hinüber, Oskar (1997). A Handbook of Pali Literature (1st Indian ed.). New Delhi: Munishiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 87–93. ISBN 81-215-0778-2.

3. Oldenberg 1879.

4. Tripāṭhī, Śrīdhara, ed. (2008). Encyclopaedia of Pali Literature: The Pali canon. 1. Anmol. p. 117. ISBN 9788126135608.

5. Geiger's discussion of the historicity of the Mahavamsa;Paranavitana and Nicholas, A concise history of Ceylon(Ceylon University Press) 1961

6. K. Indrapala, Evolution of an Ethnicity, 2005

7. Harris, Elizabeth (2006). Theravada Buddhism and the British Encounter: Religious, Missionary and Colonial Experience in Nineteenth Century Sri Lanka (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 0415544424.

8. Kemper, Steven (1992). The Presence of the Past: Chronicles, Politics, and Culture in Sinhala Life(1st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 33. ISBN 0801423953.

9. Mahavamsa. Ceylon Government. 1912.

10. In general, regarding the Mahavamsa's point-of-view, see Bartholomeusz, Tessa J. (2002). In Defense of Dharma: Just-war Ideology in Buddhist Sri Lanka. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1681-4.

11. Senewiratne, Brian (4 February 2012). "Independence Day: A Day For Action, Not Mourning". Colombo Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

12. E. F. C. Ludowyk's discussion of the connection between religion in the Mahavamsa and state-power is discussed in Scott, David (1994). "Historicizing Tradition". Formations of Ritual: Colonial and Anthropological Discourses on the Sinhala Yaktovil. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-0-8166-2255-9..

13. "Mahavamsa, the great chronicle". Sunday Observer. 29 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

14. Dr. Hema Goonatilake, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. 2003

15. H. Bechert, "The beginnings of Buddhist Historiography in Ceylon, Mahawamsa and Political Thinking", Ceylon Studies Seminar, Series 2, 1974

16. Communal politics under the Donoughmore Constitution, 1931–1947, Tissara Publishers, Colombo 1982

17. Hindu Organ, June 1, 1939 issue (Newspaper archived at the Jaffna University Library)

18. Rhoads Murphey (February 1957). "The Ruin of Ancient Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 16 (2): 181–200. doi:10.2307/2941377. JSTOR 2941377.

19. E.J. Thomas. (1913). BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES. Available: http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/busc/busc03.htm. Last accessed 26 03 10.

20. Thomas R. Trautmann. “Consanguineous Marriage in Pali Literature.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 93, no. 2, 1973, pp. 158–180. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/598890. Accessed 14 May 2020.

21. Wilhelm Geiger (1912). Mahavamsa: Great Chronicle of Ceylon. New Dehli: Asian Educational Services. 16-20.

Bibliography

• Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena (2003). Dictionary of Pali Proper Names. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1823-7.

• Oldenberg, Hermann (1879). Dipavamsa. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0217-5.

Editions and translations

• Geiger, Wilhelm; Bode, Mabel Haynes (transl.); Frowde, H. (ed.): The Mahavamsa or, the great chronicle of Ceylon, London : Pali Text Society 1912.

• Guruge, Ananda W.P.: Mahavamsa. Calcutta: M. P. Birla Foundation 1990 (Classics of the East).

• Guruge, Ananda W. P. Mahavamsa: The Great Chronicle of Sri Lanka, A New Annotated Translation with Prolegomena, ANCL Colombo 1989

• Ruwan Rajapakse, Concise Mahavamsa, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2001

• Sumangala, H.; Silva Batuwantudawa, Don Andris de: The Mahawansha from first to thirty-sixth Chapter. Revised and edited, under Orders of the Ceylon Government by H. Sumangala, High Priest of Adam's Peak, and Don Andris de Silva Batuwantudawa, Pandit. Colombo 1883.

• Turnour, George (C.C.S.): The Mahawanso in Roman Characters with the Translation Subjoined, and an Introductory Essay on Pali Buddhistical Literature. Vol. I containing the first thirty eight Chapters. Cotto 1837.

Early translation of a Sinhalese version of the text

• Upham, Edward (ed.): The Mahavansi, the Raja-ratnacari, and the Raja-vali : forming the sacred and historical books of Ceylon; also, a collection of tracts illustrative of the doctrines and literature of Buddhism: translated from the Singhalese. London : Parbury, Allen, and Co. 1833; vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3

External links

• Geiger/Bode Translation of the Mahavamsa

• The Mahavamsa: The Great Chronicle of Sri Lanka

• "Concise Mahavamsa" on-line version of: Ruwan Rajapakse, P.E. (2003). Concise Mahavamsa: History of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Maplewood, NJ : Ruwan Rajapakse. ISBN 0-9728657-0-5.

• History of Sri Lanka

• Original Pali Text in Devanagari (अन्य > महावंस > पथमपरिच्छेद to तिसट्ठिम परिच्छेद )

**************************

Mahanama in the Pali Literature

by R. Siddhartha

The Indian Historical Quarterly 8:3 1932.09 pp.462--465 p.462

Mahanama in the Pali Literature

There are four persons by the name of Mahanama in the Pali literature of whom one is a king; the second is said to be the resident monk of the Dighasanda monastery at Anuradhapura, to whom king Moggallana (497-515 A.C.) offered a monastery called Pabbata Vihara built by him (Mahavamsa, ch. 39. v. 42);

In Southeast Asia, a Pali work referred to as the 'Extended Mahavamsa' includes not only the text of the Sri Lankan Mahavamsa, but also elements of the Thupavamsa, Buddhavamsa, Mahavamsa commentaries, and quotations from various jatakas. It is sometimes referred to in academic literature as the 'Kambodian Mahavamsa' or 'Khmer Mahavamsa' because it is distinguished by being recorded in the Khmer script. Its composition is attributed to an otherwise unknown monk called Moggallana and its exact date of composition and origin are unknown, but suspected to be Burma or Thailand.

-- Mahavamsa, by Wikipedia

the third is mentioned in the concluding lines of the commentary on the Patisambhidamagga as the author of that work who lived in the reign of Kumara Dhatusena, son of king Moggallana (515-524 A.C.);

The Patisambhidamagga (paṭisambhidā-; Pali for "path of discrimination"; sometimes called just Patisambhida for short; abbrevs.: Paṭis, Pṭs) is a Buddhist scripture, part of the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhism. It is included there as the twelfth book of the Sutta Pitaka's Khuddaka Nikaya. Tradition ascribes it to the Buddha's disciple Sariputta. It comprises 30 chapters on different topics, of which the first, on knowledge, makes up about a third of the book.

Tradition ascribes the Patisambhidamagga to the Buddha's great disciple, Sariputta. It bears some similarities to the Dasuttarasutta Sutta of the Digha Nikaya, which is also attributed to Sariputta.

According to German tradition of Indology this text was likely composed around the 2nd century CE. Indications of the relative lateness of the text include numerous quotations from the Sutta and Vinaya Pitaka, as well as an assumed familiarity with a variety of Buddhist legends and stories -- for example, the names of various arahants are given without any discussion of their identities. The term patisambhida does not occur in the older sutra and vinaya texts, but does appear in both the Abhidhamma and several other Khuddaka Nikaya texts regarded as relatively late. A variant form, pratisamvid, occurs in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit and suggests that the concept itself was shared with other, non-Theravada sects. The Patisambhidamagga is also included in the Dipavamsa in a list of texts rejected by the Mahasanghikas. On the basis of this reference and certain thematic elements, AK Warder suggested that some form of the text may date to the 3rd Century BCE, the traditional date ascribed to the schism with the Mahasanghikas. L. S. Cousins associated it with the doctrinal divisions of the Second Buddhist Council and dated it to the first century BCE.

The Patisambhidamagga has been described as an "attempt to systematize the Abhidhamma" and thus as a possible precursor to the Visuddhimagga. The text's systematic approach and the presence of a matika summarizing the contents of the first section are both features suggestive of the Abhidhamma, but it also includes some features of the Sutta Pitaka, including repeated invocation of the standard sutta opening evaṃ me suttaṃ ('thus have I heard'). Its content and aspects of its composition overlap significantly with the Vibhanga, and A.K. Warder suggested that at some stage in its development it may have been classified as an Abhidhamma text.

Noa Ronkin suggests that the Patisambhidamagga likely dates from the era of the Abhidhamma's formation, and represents a parallel development of the interpretive traditions reflected by the Vibhanga and Dhammasangani...

The Patisambhidamagga was one of the last texts of the Pali Canon to be translated into English. Its technical language and frequent use of repetition and elision presented a challenge to translators and interpreters. A first translation by Bhikkhu Nanamoli was published posthumously, following extensive editing and reworking by AK Warder.

-- Paṭisambhidāmagga, by Wikipedia

and the fourth occurs in the concluding passage of the commentary on the Mahavamsa as the author of the original work. The last two of these four Mahanamas were undoubtedly great Pali scholars. Let us first see who were the three Mahanama Theras.

The commentator of the Patisambhidamagga says that he finished his work in the third year after the death of king Moggallana. So he must have lived at the time of king Moggallana and his son Kumara Dhatusena. His reference to the dead king Moggallana but not to the reigning king Kumara Dhatusena indicates his close association with the former. So it seems that he was the Thera Mahanama to whom king Moggallana presented a monastery called the Pabbata Vihara. Again, as he was a resident of the Dighasanda monastery he might have also been the author of the Mahavamsa as its commentator attributes that work to Mahanama Thera of the Dighasanda monastery. It is, however, difficult to identify these two theras because the thera Mahanama to whom the Pabbata monastery was presented was living at the Dighasanda monastery at the time when that presentation was made, and afterwards he must have been living at the new monastery built by the king. But the Thera Mahanama who wrote the commentary on the Patisambhidamagga lived, according to his own words, in a monastery known as the Uttaramanti Parivena. It is probable that the thera Mahanama who resided at one time at the Dighasanda monastery left it again for the Uttaramanti Parivena where he wrote the commentary on the Patisambhidamagga. It may also be that these two names, Dighasanda Parivena and Uttaramanti Parivena referred to one and the same monastery where Mahanama thera lived both during the life-time and after the death of king Moggallana. The commentator of the Mahavamsa says that Dighasanda was a nickname of a certain general of King Devanampiya Tissa and that he built the monastery known after his name.

In the Culavamsa (ch. 38, v. 16-17) it is stated that king Dhatusena in his boyhood lived as a novice under a thera who was his mother's brother and who was residing at the Dighasanda monastery. Here the name of the thera is not given. Is he the thera Mahanama to whom king Moggallana made a gift of the Pabbata Vihara, and is he also the author of the Mahavamsa?

According to a statement in the Culavamsa (ch. 38, v. 59) it seems that king Dhatusena was a lover of history and he was instrumental for the compilation of the Mahavamsa. The statement referred to is that king Dhatusena at the end of an anniversary celebration held in honour of the great Mahinda thera, who introduced Buddhism into Ceylon, ordered the promulgation of the chronicle of Ceylon throughout the Island, and for that purpose he gave a thousand coins. This indicates that a new work had come into existence which was not yet become popular, and this must have been the composition of Mahanama of the Dighasanda Parivena. All these facts go to show that the thera Mahanama of the Dighasanda monastery who wrote the Mahavamsa and the thera Mahanma of the Dighasanda monastery who was the favourite monk of king Moggallana, son of king Dhatusena, and the resident thera of the Dighasanda monastery were one and the same person. King Dhatusena is said to have come to the throne in 1006 B.E. (i.e. 463 A.D.) and king Moggallana died in 1060 B.E. (i.e. 517 A.D.). Now from the accession of king Dhatusena to the death of king Moggallana there were only 54 years. King Dhatusena did not die an old man. He met with an unnatural death at the hands of his eldest son, king Kassapa of Sigiriya fame. So when Dhatusena came to the throne he could not have been an old man. Then at the time of king Moggallana's death the age of Mahanama there could be between 79 and 89.(1) [I am, however, not inclined to accept that the thera Mahanama who wrote the commentary on the Patisambhidamagga was the same person as the author of the Pali Mahavamsa because a work of the former kind cannot be expected from such an old person, however clever he might have been.]

The view that the uncle of King Dhatusena was the author of the Mahavamsa could be proved further by the following fact:

The Mahavamsa stops abruptly in the middle of the 37th chapter without concluding it in the usual way with a verse in a different metre. This indicates that the author either could not finish his work owing to some unexpected trouble or died before he could complete it. Or, it might have been that the original work in Sinhalese ended there and he did not add anything to it. He only put into Pali verse what he found in the original Sinhalese version and stopped there.

The first two arguments cannot be the reasons for this abrupt ending because he had only one verse to compose to conclude it in the usual way, and this he could have done very easily. If the last one was the actual reason, it is difficult to understand why he did not finish it in the usual way. Its commentator also has not given any reason for this abrupt ending. That the old Sinhalese Mahavamsa ended just at the point where the Pali Mahavamsa stops is proved by the earlier Pali work, I mean, the Dipavamsa. It also stops exactly at the same place. His abrupt ending, I think, is due to the fact that Mahanama thera translated the Sinhalese Mahavamsa into Pali but as he wanted to write the chronicle further and bring the history up to his time he did not conclude it in the usual way. But before he could do so his benefactor king Dhatusena was put to death by his own son, Kassapa, and consequently there was much trouble in the country and the bhikkhus could not fufil his desire and the work remained unfinished till thera Dhammakitti took up the work after about seven centuries. This shows very clearly that king Dhatusena was instrumental for the writing of the Mahavamsa, and the chronicle of Ceylon which he ordered for promulgation was none but this work. Of course, the word used for the work in narration is Dipavamsa. But I do not think that it was used to indicate the work now known by that name. It was not used here as the special title of a particular book, but as denoting "the Vamsa of the Dipa," i.e. the chronicle of the Island. It could not be that king Dhatusena wanted to propagate that work called the Dipavamsa because it was defective and the defects were well-known. And moreover it was already popular in spite of its defects. So it is certain that the chronicle which king Dhatusena wanted to promulgate was not the work which we now call Dipavamsa. Therefore the Dipavamsa, that is the chronicle of the island, which he wanted to propagate was either the Sinhalese Mahavamsa preserved in the Mahavihara or the new work in Pall composed by Mahanama thera. But, as that Sinahlese work was also already popular surely it must have been this new work that he wanted to propagate.

It should be noted here that the word Mahavamsa was also not the name given to the book written by Mahanama thera. It was always referred to by its commentator as the Padyapadoruvamsa. This term mean the Mahavamsa in verse (Padyapada = metrical lines and uruvamsa = mahavamsa). This name shows also the nature of the book. It is Mahavamsa, but unlike the then existing Mahavamsa it is in metrical form. This shows again that the history of Ceylon that existed in prose was known as the Mahavamsa and the new work composed in Pali was given the name of Padyapadoruvamsa just to distinguish it from the first one. I have found that the commentator has used this name in no less than 12 places but never the name Mahavamsa.

It is noteworthy here that the author of the Pali Mahavamsa in his opening verse uses the term Mahavamsa. But the commentator says that the author referred by that word to the then existing Sinhalese Mahavamsa and not to the one composed in Pali.

R. SIDDHARTHA