Part 2 of 2

Multiproduct branding strategyMultiproduct branding strategy is when a company uses one name across all their products in a product class. When the company's trade name is used, multiproduct branding is also known as corporate branding, family branding or umbrella branding. Examples of companies that use corporate branding are Microsoft, Samsung, Apple, and Sony as the company's brand name is identical to their trade name. Other examples of multiproduct branding strategy include Virgin and Church & Dwight. Virgin, a multination conglomerate uses the punk inspired, handwritten red logo with the iconic tick for all its products ranging from airlines, hot air balloons, telecommunication to healthcare. Church & Dwight, a manufacturer of household products displays the Arm & Hammer family brand name for all its products containing baking soda as the main ingredient. Multiproduct branding strategy has many advantages. It capitalises on brand equity as consumers that have a good experience with the product will in turn pass on this positive opinion to supplementary objects in the same product class as they share the same name. Consequently, the multiproduct branding strategy makes product line extension possible.

Product line extensionProduct line extension is the procedure of entering a new market segment in its product class by means of using a current brand name. An example of this is the Campbell Soup Company, predominately a producer of canned soups. They utilize a multiproduct branding strategy by way of soup line extensions. They have over 100 soup flavours putting forward varieties such as regular Campbell soup, condensed, chunky, fresh-brewed, organic, and soup on the go. This approach is seen as favourable as it can result in a lower promotion costs and advertising due to the same name being used on all products, therefore increasing the level of brand awareness. Although, line extension has potential negative outcomes with one being that other items in the company's line may be disadvantaged because of the sale of the extension. Line extensions work at their best when they deliver an increase in company revenue by enticing new buyers or by removing sales from competitors.

SubbrandingSubbranding is used by certain multiproduct branding companies. Subbranding merges a corporate, family or umbrella brand with the introduction of a new brand in order to differentiate part of a product line from others in the whole brand system. Subbranding assists to articulate and construct offerings. It can alter a brand's identity as subbranding can modify associations of the parent brand. Examples of successful subbranding can be seen through Gatorade and Porsche. Gatorade, a manufacturer of sport-themed food and beverages effectively introduced Gatorade G2, a low-calorie line of Gatorade drinks. Likewise, Porsche, a specialised automobile manufacturer successfully markets its lower-end line, Porsche Boxster and higher-end line, Porsche Carrera.

Brand extensionBrand extension is the system of employing a current brand name to enter a different product class. Having a strong brand equity allows for brand extension. Nevertheless, brand extension has its disadvantages. There is a risk that too many uses for one brand name can oversaturate the market resulting in a blurred and weak brand for consumers. Examples of brand extension can be seen through Kimberly-Clark and Honda. Kimberly-Clark is a corporation that produces personal and health care products being able to extend the Huggies brand name across a full line of toiletries for toddlers and babies. The success of this brand extension strategy is apparent in the $500 million in annual sales generated globally. Similarly, Honda using their reputable name for automobiles has spread to other products such as motorcycles, power equipment, engines, robots, aircraft, and bikes.

Co-brandingCo-branding is a variation of brand extension. It is where a single product is created from the combining of two brand names of two manufacturers. Co-branding has its advantages as it lets firms enter new product classes and exploit a recognized brand name in that product class. An example of a co-branding success is Whitaker's working with Lewis Road Creamery to create a co-branded beverage called Lewis Road Creamery and Whittaker's Chocolate Milk. This product was a huge success in the New Zealand market with it going viral.

Multibranding strategyMultibranding strategy is when a company gives each product a distinct name. Multibranding is best used as an approach when each brand in intended for a different market segment. Multibranding is used in an assortment of ways with selected companies grouping their brands based on price-quality segments. Procter & Gamble (P&G), a multinational consumer goods company that offers over 100 brands, each suited for different consumer needs. For instance, Head & Shoulders that helps consumers relieve dandruff in the form of a shampoo, Oral-B which offers inter-dental products, Vicks which offers cough and cold products, and Downy which offers dryer sheets and fabric softeners. Other examples include Coca-Cola, Nestlé, Kellogg's, and Mars.

This approach usually results in higher promotion costs and advertising. This is due to the company being required to generate awareness among consumers and retailers for each new brand name without the benefit of any previous impressions. Multibranding strategy has many advantages. There is no risk that a product failure will affect other products in the line as each brand is unique to each market segment. Although, certain large multiband companies have come across that the cost and difficulty of implementing a multibranding strategy can overshadow the benefits. For example, Unilever, the world's third-largest multination consumer goods company recently streamlined its brands from over 400 brands to centre their attention onto 14 brands with sales of over 1 billion euros. Unilever accomplished this through product deletion and sales to other companies. Other multibrand companies introduce new product brands as a protective measure to respond to competition called fighting brands or fighter brands.

Fighting brandsThe main purpose of fighting brands is to challenge competitor brands. For example, Qantas, Australia's largest flag carrier airline, introduced Jetstar to go head-to-head against the low-cost carrier, Virgin Australia (formerly known as Virgin Blue). Jetstar is an Australian low-cost airline for budget conscious travellers, but it receives many negative reviews due to this. The launching of Jetstar allowed Qantas to rival Virgin Australia without the criticism being affiliated with Qantas because of the distinct brand name.

Private branding strategyPrivate branding is also known as reseller branding, private labelling, store brands, or own brands have increased in popularity. Private branding is when a company manufactures products but it is sold under the brand name of a wholesaler or retailer. Private branding is popular because it typically produces high profits for manufacturers and resellers. The pricing of private brand product are usually cheaper compared to competing name brands. Consumers are commonly deterred by these prices as it sets a perception of lower quality and standard but these views are shifting.

In Australia, their leading supermarket chains, both Woolworths and Coles are saturated with store brands (or private labels). For example, in the United States, Paragon Trade Brands, Ralcorp Holdings, and Rayovac are major suppliers of diapers, grocery products, and private label alkaline batteries, correspondingly. Costco, Walmart, RadioShack, Sears, and Kroger are large retailers that have their own brand names. Similarly, Macy's, a mid-range chain of department stores offers a wide catalogue of private brands exclusive to their stores, from brands such as First Impressions which supply newborn and infant clothing, Hotel Collection which supply luxury linens and mattresses, and Tasso Elba which supply European inspired menswear. They use private branding strategy to specifically target consumer markets.

Mixed branding strategyMixed branding strategy is where a firm markets products under its own name(s) and that of a reseller because the segment attracted to the reseller is different from its own market. For example, Elizabeth Arden, Inc., a major American cosmetics and fragrance company, uses mixed branding strategy. The company sells its Elizabeth Arden brand through department stores and line of skin care products at Walmart with the "skin simple" brand name. Companies such as Whirlpool, Del Monte, and Dial produce private brands of home appliances, pet foods, and soap, correspondingly. Other examples of mixed branding strategy include Michelin, Epson, Microsoft, Gillette, and Toyota. Michelin, one of the largest tire manufacturers allowed Sears, an American retail chain to place their brand name on the tires. Microsoft, a multinational technology company is seriously regarded as a corporate technology brand but it sells its versatile home entertainment hub under the brand Xbox to better align with the new and crazy identity. Gillette catered to females with Gillette for Women which has now become known as Venus. The launch of Venus was conducted in order to fulfil the feminine market of the previously dominating masculine razor industry. Similarly, Toyota, an automobile manufacturer used mixed branding. In the U.S., Toyota was regarded as a valuable car brand being economical, family orientated and known as a vehicle that rarely broke down. But Toyota sought out to fulfil a higher end, expensive market segment, thus they created Lexus, the luxury vehicle division of premium cars.

Attitude branding and iconic brandsAttitude branding is the choice to represent a larger feeling, which is not necessarily connected with the product or consumption of the product at all. Marketing labeled as attitude branding include that of Nike, Starbucks, The Body Shop, Safeway, and Apple Inc.. In the 2000 book No Logo,[16] Naomi Klein describes attitude branding as a "fetish strategy". Schaefer and Kuehlwein analyzed brands such as Apple, Ben & Jerry's or Chanel describing them as 'Ueber-Brands' - brands that are able to gain and retain "meaning beyond the material."[49][50]

A great brand raises the bar – it adds a greater sense of purpose to the experience, whether it's the challenge to do your best in sports and fitness, or the affirmation that the cup of coffee you're drinking really matters. – Howard Schultz (president, CEO, and chairman of Starbucks)

The color, letter font and style of the Coca-Cola and Diet Coca-Cola logos in English were copied into matching Hebrew logos to maintain brand identity in Israel.

The color, letter font and style of the Coca-Cola and Diet Coca-Cola logos in English were copied into matching Hebrew logos to maintain brand identity in Israel.Iconic brands are defined as having aspects that contribute to consumer's self-expression and personal identity. Brands whose value to consumers comes primarily from having identity value are said to be "identity brands". Some of these brands have such a strong identity that they become more or less cultural icons which makes them "iconic brands". Examples are: Apple, Nike, and Harley-Davidson. Many iconic brands include almost ritual-like behaviour in purchasing or consuming the products.

There are four key elements to creating iconic brands (Holt 2004):

1. "Necessary conditions" – The performance of the product must at least be acceptable, preferably with a reputation of having good quality.

2. "Myth-making" – A meaningful storytelling fabricated by cultural insiders. These must be seen as legitimate and respected by consumers for stories to be accepted.

3. "Cultural contradictions" – Some kind of mismatch between prevailing ideology and emergent undercurrents in society. In other words, a difference with the way consumers are and how they wish they were.

4. "The cultural brand management process" – Actively engaging in the myth-making process in making sure the brand maintains its position as an icon.

Schaefer and Kuehlwein propose the following 'Ueber-Branding' principles. They derived them from studying successful modern Prestige brands and what elevates them above mass competitors and beyond considerations of performance and price (alone) in the minds of consumers:[51]

1. "Mission Incomparable" - Having a differentiated and meaningful brand purpose beyond 'making money.'[52] Setting rules that follow this purpose - even when it violates the mass marketing mantra of "Consumer is always Boss/right".

2. "Longing versus Belonging" - Playing with the opposing desires of people for Inclusion on the one hand and Exclusivity on the other.

3. "Un-Selling" – First and foremost seeking to seduce through pride and provocation, rather than to sell through arguments.[53]

4. "From Myth To Meaning" - Leveraging the power of myth - 'Ueber-Stories' that have fascinated- and guided humans forever.[54]

5. "Behold!" - Making product and associated brand rituals reflect the essence of the brand mission and myth. Making it the center of attention, while keeping it fresh.

6. "Living the Dream" - Living the brand mission as an organization and through its actions. Thus radiating the brand myth from the inside out, consistently and through all brand manifestations. - For "Nothing is as volatile than a dream."[55]

7. "Growth without End" - Avoiding to be perceived as omnipresent, diluting brand appeal. Instead 'growing with gravitas' by leveraging scarcity/high prices, 'sideways expansion' and other means.[56]

"No-brand" brandingRecently, a number of companies have successfully pursued "no-brand" strategies by creating packaging that imitates generic brand simplicity. Examples include the Japanese company Muji, which means "No label" in English (from 無印良品 – "Mujirushi Ryohin" – literally, "No brand quality goods"), and the Florida company No-Ad Sunscreen. Although there is a distinct Muji brand, Muji products are not branded. This no-brand strategy means that little is spent on advertisement or classical marketing and Muji's success is attributed to the word-of-mouth, a simple shopping experience and the anti-brand movement.[57][58][59]"No brand" branding may be construed as a type of branding as the product is made conspicuous through the absence of a brand name. "Tapa Amarilla" or "Yellow Cap" in Venezuela during the 1980s is another good example of no-brand strategy. It was simply recognized by the color of the cap of this cleaning products company.

Derived brandsIn this case the supplier of a key component, used by a number of suppliers of the end-product, may wish to guarantee its own position by promoting that component as a brand in its own right. The most frequently quoted example is Intel, which positions itself in the PC market with the slogan (and sticker) "Intel Inside".

Brand extension and brand dilutionThe existing strong brand name can be used as a vehicle for new or modified products; for example, many fashion and designer companies extended brands into fragrances, shoes and accessories, home textile, home decor, luggage, (sun-) glasses, furniture, hotels, etc.

Mars extended its brand to ice cream, Caterpillar to shoes and watches, Michelin to a restaurant guide, Adidas and Puma to personal hygiene. Dunlop extended its brand from tires to other rubber products such as shoes, golf balls, tennis racquets, and adhesives. Frequently, the product is no different from what else is on the market, except a brand name marking. Brand is product identity.

There is a difference between brand extension and line extension. A line extension is when a current brand name is used to enter a new market segment in the existing product class, with new varieties or flavors or sizes. When Coca-Cola launched "Diet Coke" and "Cherry Coke", they stayed within the originating product category: non-alcoholic carbonated beverages. Procter & Gamble (P&G) did likewise extending its strong lines (such as Fairy Soap) into neighboring products (Fairy Liquid and Fairy Automatic) within the same category, dish washing detergents.

The risk of over-extension is brand dilution where the brand loses its brand associations with a market segment, product area, or quality, price or cachet.

Social media brandsIn 'The Better Mousetrap: Brand Invention in a Media Democracy' (2012), author and brand strategist Simon Pont posits that social media brands may be the most evolved version of the brand form, because they focus not on themselves but on their users. In so doing, social media brands are arguably more charismatic, in that consumers are compelled to spend time with them, because the time spent is in the meeting of fundamental human drivers related to belonging and individualism. "We wear our physical brands like badges, to help define us – but we use our digital brands to help express who we are. They allow us to be, to hold a mirror up to ourselves, and it is clear. We like what we see." [60]

Multi-brandsAlternatively, in a market that is fragmented amongst a number of brands a supplier can choose deliberately to launch totally new brands in apparent competition with its own existing strong brand (and often with identical product characteristics); simply to soak up some of the share of the market which will in any case go to minor brands. The rationale is that having 3 out of 12 brands in such a market will give a greater overall share than having 1 out of 10 (even if much of the share of these new brands is taken from the existing one). In its most extreme manifestation, a supplier pioneering a new market which it believes will be particularly attractive may choose immediately to launch a second brand in competition with its first, in order to pre-empt others entering the market. This strategy is widely known as multi-brand strategy.

Individual brand names naturally allow greater flexibility by permitting a variety of different products, of differing quality, to be sold without confusing the consumer's perception of what business the company is in or diluting higher quality products.

Once again, Procter & Gamble is a leading exponent of this philosophy, running as many as ten detergent brands in the US market. This also increases the total number of "facings" it receives on supermarket shelves. Sara Lee, on the other hand, uses it to keep the very different parts of the business separate—from Sara Lee cakes through Kiwi polishes to L'Eggs pantyhose. In the hotel business, Marriott uses the name Fairfield Inns for its budget chain (and Choice Hotels uses Rodeway for its own cheaper hotels).

Cannibalization is a particular problem of a multi-brand strategy approach, in which the new brand takes business away from an established one which the organization also owns. This may be acceptable (indeed to be expected) if there is a net gain overall. Alternatively, it may be the price the organization is willing to pay for shifting its position in the market; the new product being one stage in this process.

Private labelsPrivate label brands, also called own brands, or store brands have become popular. Where the retailer has a particularly strong identity (such as Marks & Spencer in the UK clothing sector) this "own brand" may be able to compete against even the strongest brand leaders, and may outperform those products that are not otherwise strongly branded.

Designer Private LabelsA relatively recent innovation in retailing is the introduction of designer private labels. Designer-private labels involve a collaborative contract between a well-known fashion designer and a retailer. Both retailer and designer collaborate to design goods with popular appeal pitched at price points that fit the consumer’s budget. For retail outlets, these types of collaborations give them greater control over the design process as well as access to exclusive store brands that can potentially drive store traffic.

In Australia, for example, the department store, Myer, now offers a range of exclusive designer private labels including Jayson Brundson, Karen Walker, Leona Edmiston, Wayne Cooper, Fleur Wood and ‘L’ for Lisa Ho.[61] Another up-market department store, David Jones, currently offers ‘Collette’ for leading Australian designer, Collette Dinnigan, and has recently announced its intention to extend the number of exclusive designer brands.[62] Target has teamed up with Danii Minogue to produce her “Petites’ range.[63] Specsavers has joined up with Sydney designer, Alex Perry to create an exclusive range of spectacle frames while Big W stocks frames designed by Peter Morrissey.

Individual and organizational brandsWith the development of brand, Branding is no longer limited to a product or service.[64] There are kinds of branding that treat individuals and organizations as the products to be branded. Most NGOs and non-profit organizations carry their brand as a fundraising tool. The purpose of most NGOs is leave social impact so their brand become associated with specific social life matters. Amnesty International, Habitat for Humanity, World Wildlife Fund and AIESEC are among the most recognized brands around the world.[65] NGOs and non-profit organizations moved beyond using their brands for fundraising to express their internal identity and to clarify their social goals and long-term aims. Organizational brands have well determined brand guidelines and logo variables.[66]

Personal brandingMain article: Personal branding

Employer brandingMain article: Employer branding

Crowd sourced brandingThese are brands that are created by "the public" for the business, which is opposite to the traditional method where the business create a brand.

Personalised brandingMany businesses have started to use elements of personalisation in their branding strategies, offering the client or consumer the ability to choose from various brand options or have direct control over the brand. Examples of this include the #ShareACoke campaign by Coca-Cola which printed people's names and place names on their bottles encouraging people. AirBNB has created the facility for users to create their own symbol for the software to replace the brand's mark known as The Bélo.[67]

Nation branding (place branding and public diplomacy)Nation branding is a field of theory and practice which aims to measure, build and manage the reputation of countries (closely related to place branding). Some approaches applied, such as an increasing importance on the symbolic value of products, have led countries to emphasise their distinctive characteristics. The branding and image of a nation-state "and the successful transference of this image to its exports – is just as important as what they actually produce and sell."

Destination brandingDestination branding is the work of cities, states, and other localities to promote to themselves. This work is designed to promote the location to tourists and drive additional revenues into a tax base. These activities are often undertaken by governments, but can also result from the work of community associations. The Destination Marketing Association International is the industry leading organization.

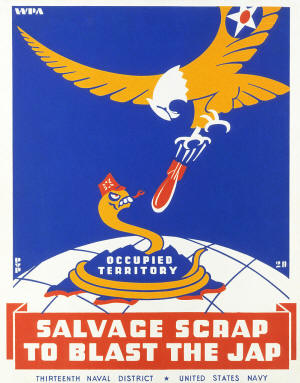

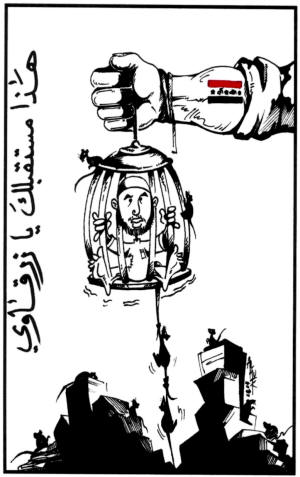

Doppelgänger brand image (DBI)A doppelgänger brand image or "DBI" is a disparaging image or story about a brand that it circulated in popular culture. DBI targets tend to be widely known and recognizable brands. The purpose of DBIs is to undermine the positive brand meanings the brand owners are trying to instill through their marketing activities.[68]

The term stems from the combination of the German words doppel (double) and gänger (walker).

Doppelgänger brands are typically created by individuals or groups to express criticism of a brand and its perceived values, through a form of parody, and are typically unflattering in nature.

Due to the ability of Doppelgänger brands to rapidly propagate virally through digital media channels, they can represent a real threat to the equity of the target brand. Sometimes the target organization is forced to address the root concern or to re-position the brand in a way that defuses the criticism.

Examples include:

• Joe Chemo campaign organized to criticize the marketing of tobacco products to children and their harmful effects.[69]

• Version of the Coca-Cola logo crafted to protest their sponsorship of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar and associated human rights abuses (see citation for original Reddit thread featuring the image).[70]

• Parody of the Pepsi logo as an obese man to highlight the relationship between soft drink consumption and obesity.[71]

• The FUH2 campaign protesting the Hummer SUV as a symbol of corporate and consumer irresponsibility toward public safety and the environment.[72]

In the 2006 article "Emotional Branding and the Strategic Value of the Doppelgänger Brand Image", Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel suggest that a doppelgänger brand image can be a benefit to a brand if taken as an early warning sign that the brand is losing emotional authenticity with its market.[68]

See also• Advertising

• Brand ambassador

• Brand architecture

• Brand engagement

• Brand equity

• Brand extension

• Brand evangelism

• Brand loyalty

• Brand management

• Brand valuation

• Co-branding

• Employer branding

• Green brands

• Legal name

• List of defunct consumer brands

• Marketing

• Nation branding

• No Logo

• Promotion

• Rebranding

• Terroir

• Trademark

• Trade name

• Umbrella brand

• Visual brand language

References Haigh, Robert (18 February 2014). "Ferrari – The World’s Most Powerful Brand". Brand Finance. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

American Marketing Association Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-06-29. The Marketing Accountability Standards Board (MASB) endorses this definition as part of its ongoing Common Language in Marketing Project.

Foundations of Marketing. fahy& jobber. 2015.

Bhimrao M. Ghodeswar (2008-02-29). "Building brand identity in competitive markets: a conceptual model". Journal of Product & Brand Management. 17 (1): 4–12. ISSN 1061-0421. doi:10.1108/10610420810856468.

Keller, Kevin Lane (1993-01-01). "Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity". Journal of Marketing. 57 (1): 1–22. JSTOR 1252054. doi:10.2307/1252054.

ranchhod, 2004

Briciu, V.A, and Briciu, A., "A Brief History of Brands and the Evolution of Branding," Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov [Series VII: Social Sciences], Vol. 9 (58) No. 2 2016, p.137 <Online:

http://webbut.unitbv.ro/bulletin/Series ... Briciu.pdf Sanskrit Epic Mahabharat, Van Parva, p. 3000, Shalok 15–22

Johnson, Ken (5 March 2015). "Review: ‘Ennion,’ at the Met, Profiles an Ancient Glassmaker". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

Colapinto, John (3 October 2011). "Famous Names". The New Yorker. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

"(U.S.) Trademark History Timeline". Lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

Jstor.org

Hibbert, Colette (2008-01-10). "Golden celebration for 'oldest brand'". BBC News UK.

Maverick, L. A. (Jan 1942). "The Term "Maverick," Applied to Unbranded Cattle". California Folklore Quarterly. Western States Folklore Society. 1 (1): 94–96. JSTOR 1495731. doi:10.2307/1495731.

Mildred Pierce, Newmediagroup.co.uk ArchivedDecember 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

[page needed] Klein, Naomi (2000) No logo, Canada: Random House, ISBN 0-676-97282-9

"Brand Recognition Definition". Investopedia. 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

http://przemekkowal.com Kotler,, Philip (2009). Principles of marketing. Pearson Education Australia. ISBN 9781442500419.

Compare: Franzen, Giep; Moriarty, Sandra E. (2015-02-12) [2009]. "1: The Brand as a System". The Science and Art of Branding. London: Routledge (published 2015). p. 19. ISBN 9781317454670. Retrieved 2016-08-16. This deeper meaning, the core values, character, or essence of a brand, is what Upshaw (1995) refers to when they use the term brand identity. However, that expansion of the meaning of brand identity causes some confusion because it overlaps with other common branding terms, such as brand image, brand personality, and brand meaning. [...] Brand identity and brand image are only two of the buzz words that are used and confused by brand experts and brand managers.

Madhavaram, Sreedhar; Badrinarayanan, Vishag; McDonald, Robert E. (2005-12-01). "INTEGRATED MARKETING COMMUNICATION (IMC) AND BRAND IDENTITY AS CRITICAL COMPONENTS OF BRAND EQUITY STRATEGY: A Conceptual Framework and Research Propositions". Journal of Advertising. 34 (4): 69–80. ISSN 0091-3367. doi:10.1080/00913367.2005.10639213.

Tan, Donald (2010). "Success Factors In Establishing Your Brand" Franchising and Licensing Association. Retrieved from

http://www.flasingapore.org/info_branding.php Chitty, Williams (2005). integrated marketing communications. Thomson. ISBN 0 17 012008 2.

Percy, Larry; Rossiter, John R. (1992). "A model of brand awareness and brand attitude advertising strategies". Psychology and Marketing. 9 (4): 263. doi:10.1002/mar.4220090402.

Macdonald, Emma K; Sharp, Byron M (2000-04-01). "Brand Awareness Effects on Consumer Decision Making for a Common, Repeat Purchase Product:: A Replication". Journal of Business Research. 48 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00070-8.

Robert Pearce. "Beyond Name and Logo: Other Elements of Your Brand « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

http://www.adweek.com/news/advertising- ... age-160228 Shirazi A, Lorestani HZ, Mazidi AK. Investigating the effects of brand identity on customer loyalty from social identity perspective. Iranian Journal of Management Studies. 2013;6(2):153-78.

Belch, G .E (2012). Advertising and promotion: an integrated marketing communications perspective. New York, NY United States of America: McGrawHill Irwin.

Dahlen M, Lange F, Smith T. Marketing communications: A brand narrative approach. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

Shimp TA. Integrated marketing communications in advertising and promotion. 8 ed. Mason, OH United States of America: South Western, Cengage Learning; 2009.

Uzunolu, E. and Kip, S.M., 2014. Brand communication through digital influencers: Leveraging blogger engagement. International Journal of Information Management, [online] 34(5), pp.592–602. Available at: <http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0268401214000450> [Accessed 21 Feb. 2015]

Kim, E., Sung, Y. and Kang, H., 2014. Brand followers' retweeting behavior on Twitter: How brand relationships influence brand electronic word-of-mouth. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, pp.18–25

.McKee, S., 2014. Branding Made Simple. [online] Bloomberg Business. Available at: <http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-10-13/branding-made-simple> [Accessed 6 Feb. 2015]

Riefler, P., 2012. Why consumers do (not) like global brands: The role of globalization attitude, GCO and global brand origin. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), pp.25–34

Sappington, D.E.M. and Wernerfelt, B., 1985. To Brand or Not to Brand? A Theoretical and Empirical Question. The Journal of Business, [online] 58(3), p.279. Available at: <http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/296297> [Accessed 17 Apr. 2015]

Anon., 2009. Idea Branding. [online] The Economist. Available at: <http://www.economist.com/node/14126533> [Accessed 1 Feb. 2015]

Schmitt, B., 2012. The consumer psychology of brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, [online] 22(1), pp.7–17. Available at: <http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1057740811001008> [Accessed 1 Feb. 2015]

Anon., 2007. Sensory branding Sound effects. [online] The Economist. Available at: <http://www.economist.com/node/9079881> [Accessed 5 Feb. 2015]

"MerriamAssociates.com". MerriamAssociates.com. 2012-11-15. Archived from the original on 2009-08-22. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

http://product.okfn.org Neumeier, Marty (2004), The Dictionary of Brand. ISBN1-884081-06-1, pp.20

O'Connor, Z. "Logo colour and differentiation: A new application of environmental colour mapping". Color Research & Application, 36 (1), pp. 55–60. Also available from Colour & Design Research.

Paul S. Richardson, Alan S. Dick and Arun K. Jain "Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cue Effects on Perceptions of Store Brand Quality", Journal of Marketing October 1994 pp. 28-36

Bianca (2010-12-10). "Wikileaks, Hacktivism and Brands as Political Symbols « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

Giesler, Markus (2012), "How Doppelgänger Brand Images Influence the Market Creation Process: Longitudinal Insights from the Rise of Botox Cosmetic," Journal of Marketing, November 2012.

"General Motors: A Reorganized Brand Architecture for a Reorganized Company « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. 2010-11-22. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

Nisha Roy (nisharoy) – Pearltrees. "Brand Architecture: Strategic Considerations « Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies". Merriamassociates.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

Schaefer, Wolf and Kuehlwein, JP. 2015. Rethinking Prestige Branding - Secrets of the Ueber-Brands. Kogan Page. p.17. ISBN 9780749470036

Mathur, Sarita, Kuehlwein, JP and Schaefer, Wolf. Ueber-Brands- How to make you brand priceless. Asia Management Insights, Singapore Management University. vol.3 2016

Schaefer, Wolf and Kuehlwein, JP. 2015. Rethinking Prestige Branding - Secrets of the Ueber-Brands. Kogan Page. ISBN 9780749470036

Kuehlwein, JP and Schaefer, Wolf. How modern prestige brands create meaning through mission and myth. Journal of Brand Strategy. Henry Stewart Publications. Vol.5 Nr.4. Spring 2017. ISSN 2025855x

Kuehlwein, JP. Un-Sell To Seduce... and be thanked with a premium.

http://www.ueberbrands.com 12/2015

Kuehlwein, JP and Schaefer, Wolf. Myth Making - The Holy Grail Of Today's Ueber-Brands. Marketing Review St.Gallen. pp.64ff. 1/2016

Schaefer, Wolf and Kuehlwein, JP. 2015. Rethinking Prestige Branding - Secrets of the Ueber-Brands. Kogan Page. p.174. ISBN 9780749470036

Kuehlwein, JP. How Premium Brands Grow Without Loosing Their Glow.

http://www.ueberbrands.com 02/2013

"Muji brand strategy, Muji branding, no name brand". VentureRepublic. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

Matt Heig, Brand Royalty: How the World's Top 100 Brands Thrive and Survive, pg.216

EMEASEE.com[permanent dead link]

[1], 'The Better Mousetrap: Brand Invention in a Media Democracy' (2013) Simon Pont. Kogan Page. ISBN 978-0749466213

Schetzer, A., "Private Labels in Designer Sheep's Clothing, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 September 2014 Online:http://www.smh.com.au/business/private-labels-in-designer-sheeps-clothing-20140925-10ilia.html

Roy Morgan Research,"Private Label Could be the New Black" Research Finding no. 5613, [Media Release] May, 2014 Online:

http://roymorgan.com.au/findings/5613-p ... 1405292337 Roy Morgan Research, "Target On Target for New Era Women's Fashion," Research Finding, no. 5756, August, 2014 Online:

http://roymorgan.com.au/findings/5756-t ... 1408260520 "Is Your Personal Brand Working For or Against You?". The Wall Street Journal. 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2015-02-01.

"The Role of Brand in the Nonprofit Sector (SSIR)". ssir.org. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

"AIESEC BLUE BOOK Brand Toolkit" (PDF).

"Airbnb says its new logo belongs to everyone". Archived from the original on September 21, 2014.

Thompson, Craig J.; Rindfleisch, Aric; Arsel, Zeynep (2006-01-01). "Emotional Branding and the Strategic Value of the Doppelgänger Brand Image". Journal of Marketing. 70 (1): 50–64. ISSN 0022-2429. doi:10.1509/jmkg.2006.70.1.50.

"Joe Chemo: A Camel Who Wishes He'd Never Smoked".

http://www.joechemo.org. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

"Coke's slogan is "Share Happiness". So I made an ad to remind them of the kind of happiness they're sharing in Qatar. • /r/sports". reddit. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

"Designer Makes Fun Of Pepsi, Turns Its Logo Into A Fat Man - DesignTAXI.com". designtaxi.com. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

"FUH2 | Fuck You And Your H2".

http://www.fuh2.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-19. Retrieved 2015-09-10.