The Chronicles of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Accessed: 7/10/19

[Transcribed from the video by Tara Carreon]

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

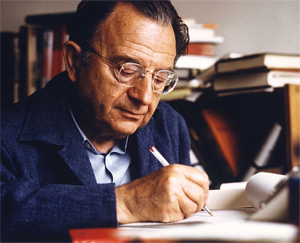

Richard Arthure on Meeting Chogyam Trungpa

There are two intertwined narratives. For me, one is specifically the story of Trungpa Rinpoche, and how I directly experienced that. And the other is my own path, and how that was influenced by him, and how that also went on in a certain way because of maybe seeds that he planted that went to fruition after he died. So those two interwoven narratives, it’s hard for me to separate them out because they are both experiential from my point of view.

Well, I met him in 1966. And at that time I was married to an Irish actress named Jacqueline Ryan, or Jackie. We had rather a stormy relationship. We used to fight like cats and dogs. So kind of a trigger event that led to my meeting him was that I got a phone call from kind of an ex-girlfriend, an American girl one day, and she was asking me if I’d like to try LSD. And I had tried it before, so I said, “Yeah, I am very curious, and would be willing to try it.” So we arranged to meet. I actually had a day job at the time. I mean, I had some on and off career in theatre and acting and film and so on. But at that time I had a day job. And I called in sick one day, and I went to meet her. And she had some of this “Sunshine” [Orange sunshine] acid that’s supposed to be really good. Of course, I had no standard of comparison as to what was going to happen, but for me it was an extraordinary experience.

And I remember being in her room, looking at the wall, and seeing sort of dancing molecules, and getting the sense that things were not at all as solid as I had supposed. It was quite remarkable. And then later we went out in the park, Kensington Park, and laid down on the grass, and looked up at the sky, and I could see these pulsing, circular patterns in the sky. It was very extraordinary. I mean, I never heard the word “mandala,” but I suppose that that was the kind of thing I was seeing. These circular patterns were very vivid.

And so eventually, towards 4:30 or so in the afternoon, I said, “I should be going home, because my wife will be coming home from work.” So I went home, and I didn’t immediately tell Jackie that I had taken this drug, LSD. Later on I told her, and she was very shocked, and she wanted me to promise that I would never take LSD again, which I refused to do, because it had been a kind of experience that had opened a sort of door, you know, the “doors of perception,” or whatever it might be.

But anyway, when we took the acid together, the girl named Karen, she had a book that supposedly was based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. It was written by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, or later, Ram Dass -- right? The classic story of the 60s, I suppose. And I was so curious because of the extraordinary experience I had, that I wanted to find the original Tibetan Book of the Dead. So I went to this esoteric bookstore in London and I asked, “Do you have the Tibetan Book of the Dead?” They said, “Oh, no, no, it’s out of print. It’s been out of print for a while. But wait a minute, we have a used copy of another book in that same series that was edited by Evans-Wentz, it’s called ‘Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines.’ Would you be interested in that one?” And I said, “Okay, Let me have a look.” So I ended up buying this used copy of this book, “Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines.”

And it turned out it was all about the six yogas of Naropa, about which previously I knew nothing at all. And it somehow seemed really fascinating to me. And I started trying to meditate on my own. And I remember one day my wife Jackie came into our flat in London, and she saw me sitting cross-legged on the floor, and she said, “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” And I said, “Well, I’m trying to meditate.” She said, “Ha! A bastard like you could never meditate!” So it was kind of a negative reaction, and internally my response to that was, “I’m going to meditate if it kills me.”

So I was very determined to keep going. And actually, the book also said that, “You can’t hope to attain enlightenment unless you connect with a realized master in the practice lineage.” So then I was thinking, “Well, how on earth am I going to do that, because Tibet is on the other side of the planet, and I’m here in London, and I have no connection with anything to do with that.” But I began making the aspiration in my mind, “May I connect with a realized master in the practice lineage.” And I was actually trying to visualize the Kagyu gurus above my head. I had no idea what they looked like. I didn’t even know they wore maroon robes or anything like that. So I was supplicating without knowing what they looked like, or anything like that.

So one day in my mind I was making this aspiration, and I had this sudden thought come to my mind, “Go to the phone book and look up ‘Tibet.’” And I thought, “That’s crazy. What’s that going to do?” And I thought, “Yeah, yeah, but what have you got to lose?” So I went to the phone book, and I looked up “Tibet.” Now in London, there’s 12 million people, the phone book is in four volumes, but I looked up in the “T’s,” and there was only one entry that began with the word “Tibet.” And that was “The Tibet Society of the United Kingdom.”

So I saw that, and noted down the address -- I think it was 58 Eccleston Square -- and I didn’t think of phoning. I thought, “Well, I’ll go in person to see what happens.”

So at that time I had this great old car called a “Wolseley”. It was a very beautiful car. It only had one defect: the reverse gear didn’t work. So later on Trungpa Rinpoche used that as an analogy when joining the Vajrayana path, being a car with no reverse, and he got plenty of experience in being in that car without a reverse, I can assure you.

On any journey there is the assumption that we should be allowed to avoid danger along the way — at the minimum, to be a little careful. But if we think there is a reverse gear in Shambhala vision, we are misunderstanding a basic reality: life is perpetual motion.

-- Bravery: The Vision of the Great Eastern Sun, by Sakyong Mipham

But anyway, so I got in the car, and I knew where Eccleston Square was, and I managed to find a parking place there without having to use the reverse. And it was sort of a Victorian townhome. And I went up the steps and there was a brass plate that said, “Buddhist Society.” And I thought, “Ha, that’s a good sign.” And underneath it it said, “Tibet Society.” So I pressed that bell push, the buzzer sounded, the door opened, and I went in.

And there was an arrow pointing down to the basement. So I went down to the basement, full of anticipation that there was going to be something very esoteric -- I was sure about that – “Tibet Society!” And there was this middle-aged English woman with her hair in a bun, typing away on an old manual typewriter, looking at me at the top of her glasses and saying, “How can we help you?” And I said, “Well, tell me about the Tibet Society.” And she said, “Oh, it’s a charitable organization, raising money for Tibetan refugees in India. Would you care to make a donation?” I thought, “This is crazy.” And I think I gave her 10 shillings, and I was about to leave, thinking that this was a total waste of time. And at that moment, a young woman came in the door, and she kind of pulled me aside and she said, “If you don’t mind me asking, ‘what are you doing here’?” I said, “Well, it’s really hard to explain, but I’m really interested in the teachings of the Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism.” She said, “Oh, you know there are two Tibetan lamas in this country, and they belong to that Kagyu order.” And then she reached into her purse and she pulled out a photo, and she pointed to the one on the left and she said, “That’s Trungpa. That’s the one you want to meet.” I said, “Yes. Okay.” And then she proceeded to give me the address and phone number. They were living in Oxford.

And so I was very excited. She actually gave me the photo. And I remember going into the park -- it was in the summer -- and sitting on the grass and trying to meditate. And I was looking at this photo – I had it on the grass in front of me – and I could see this kind of aura around the head of Trungpa Rinpoche in the photo. And I felt the hairs on the back of my neck standing up, and I thought, “I have to contact him. I can’t wait any longer.” And I rushed home, and I phoned the number in Oxford, and asked to speak to Venerable Trungpa, and someone with a weird foreign accent said, “Oh, he no here right now. Better you write to him.” And then they gave me an address of some place called Biddulph in Staffordshire, Biddulph Old Hall in Staffordshire.

And so I sat down and wrote a letter, “Dear Venerable Trungpa. I’d very much like to come and meet you, and study under your guidance. And I’d be willing to meet you any time or place that would be suitable to you.”

And then I remember I still had this book that I had borrowed from the Tibet Society, “Tibet’s Great Yogi, Milarepa.” And one of the illustrations in that was a very elaborate syllable “Hum.” And so I carefully copied that in the margin of the letter in a green felt tip pen, this sort of syllable “hum.” And then I was satisfied. And I sent off the letter sure that that would do the trick.

And then I decided that I should fast until I would get a response to my letter. So for about 4 hours I didn’t eat anything at all. And then I got really hungry, and had a good meal, and felt much better. And that was the end of my fast.

So I sent off the letter, and of course, the first day there’s no response. The second day there’s no response. The third day, now by that time you could get an answer, because in England you could send a letter one day and it would get there the next day, and you could get a reply the day after that. But on the third day there was still no answer. On the fourth day there was still no answer. Now I was getting antsy. And on the fifth day still no answer. And I thought, “Well, I can’t wait any longer. I’m just going to go.” And I had the address of this place, The Biddulph Old Hall, Biddulph, Staffordshire. And I had a road atlas. So I found this place Biddulph. It was like a dot on the map, it was just this little village. And I decided I was going to go. And I had this sort of Mexican blanket that someone had given me, and the other book that they had loaned me was “Tibet’s great yogi, Milarepa” from the Tibet Society. So I had the book, I had the blanket, and I was all ready to go.

So my wife sees me getting ready, and she says, “Where on earth are you going?” And I said, “Well, don’t wait up for me; I’ll probably be back really late.” And I didn’t explain. I didn’t want to go into any discussion, because she had such a bad attitude when she saw me trying to meditate.

So I just got in the car, with no reverse, and headed out. And I finally found this little village called “Biddulph” in Staffordshire. It’s kind of in the middle of England. And then I stopped in the village, and got directions to the Old Hall. And it’s a beautiful stone manor house. It fortunately had a kind of circular driveway, so I was able to drive in and have a hope of getting back out again in my car.

And this place had a kind of iron knocker on the door. And I knocked, and a young man came to the door and said, “How can we help you?” And I said, “Well, I came to see the Venerable Trungpa.” And he said, “Ah, you must be Richard. He told us you’d be arriving today.” And I said, “What?,” because I had not had any answer to my letter. So I was completely baffled. “Yeah, come on in, come on in,” you know.

Then he took me upstairs and knocks on the door. And a voice from inside said, “Come in.” And I went in, and there was this young Tibetan in maroon robes, grinning from ear to ear like he’s extremely happy to see me. He said, “Good to see you. Come in. Tell me all about yourself.” And it was a very simple room, with a bed, a chair, a table, and that was it. And he offered me the bed to sit on, and he sat on a chair, and he was saying, “Tell me all about yourself.” Well, I didn’t know what to tell him, because there wasn’t much to tell in the context of why I came to meet him. But I actually asked him if he would accept me as a student. And he said, “It’s a pleasure to do business with you.” And then he told me that I should join in the schedule with the other people.

Now they had a very strict sitting schedule. They [Buddhist Society] had not yet connected with the Zen tradition of having walking meditation, so it was just sitting in the afternoon. So that was okay. And there was an evening meal. And then I went to him and talked to him some more. Then the next day they had sitting at 7-8, then there was breakfast, and then sitting from 9-12 with no break. And it was agony for me, because I wasn’t used to sitting cross-legged for three hours at a time without any break.

So after lunch I went up to see Rinpoche, and he said, “How’s it going?” So I didn’t know what to say, except that I had some images come up in my mind, and I tried to describe those. He actually interpreted some of them. It was very interesting. And anyway, he asked me if I would like to stay there for a week. And I said, “Yes, I would. But I think I should probably phone my wife and let her know where I am.” “Good idea! There’s a phone downstairs.”

So I went downstairs, and I phoned my wife Jackie. And I said, “I know you won’t believe this, but I’m with this Tibetan lama in this place called Biddulph in Staffordshire. And I’m going to be here for a week. So I’ll see you next Thursday,” or whatever it was. I think she thought I had flipped out, because that’s the first she had heard of it.

So during the week, he told me that the time would come when he would have his own center, which seemed at the time utterly improbable, because he was living, as it turned out, with two other Tibetans in a basement flat in Oxford. And they had virtually no money. One of them was working part-time as a porter, just enough to put a little bit of food on the table.

Job Description: Lodge Porter (Nights)

Salary: circa £21,000 p.a.

Main Purpose of Job: Responsible for the College’s security, welfare, communications and reception services.

Relationships:

• Responsible to: Lodge Manager

• Liaison with: Deans, students, staff, visitors, University Security Services and the Police

Hours of Work: Regularly working nights on a rota basis 4 days on, 4 days off. 7pm – 7am. The post holder will be asked to work day shifts, if the need arises.

Main Tasks:

Ensuring the efficient, friendly and informative reception of visitors to the College. This includes students, staff, conference guests, members of the public and contractors/suppliers;

Ensuring the prompt, efficient and friendly handling of incoming telephone calls to the Lodge switchboard;

Providing an appropriate level of response to contingencies, including emergencies, arising within and around the College, ensuring effective initial communication to and between interested parties;

Maintaining day to day security of buildings, property and persons on the College sites, including the efficient management of keys and monitoring of fire alarms, CCTV, and intruder alarms and access control systems;

Ensuring the prompt and efficient handling and of incoming and outgoing mail; this includes sorting the mail and parcels in a prompt and tidy way.

Completing College Guest room and Teaching room bookings in a timely manner.

Ensuring that good student order is maintained.

Maintaining the Lodge and entrance area as an efficient and presentable front office for the College

Safeguarding and accounting for all monies received at the Lodge,

Skills/Qualities:

The College Porters need to be: alert and vigilant; communicative; polite, patient and friendly both in person and on the telephone; capable of exercising firmness with students and responsive and pro-active in approach to the provision of help.

Experience of assisting with welfare issues is desirable.

Previous work in a College environment is ideal.

Previous experience in public reception responsibilities, and security industry is desirable.

Candidates should be PC literate.

Good level of English and Maths.

Benefits: 252 hours holiday per year, free meals on duty, uniform provided, pension, discounted travel scheme

For further information please visit http://www.oriel.ox.ac.uk and to apply please download the job description and submit an application form along with a CV via email to recruitment@oriel.ox.ac.uk or in writing to HR Department, Oriel College, Oriel Square, Oxford. OX1 4EW

Closing date for receipt of completed applications is 11th January 2019

The College exists to promote excellence in education and research and is actively committed to the principle of equality of opportunity for all suitably qualified candidates.

-- Lodge Porter (Nights), by Oriel College, University of Oxford

And I guess Rinpoche was studying a little bit at St. Antony’s college in Oxford....

Founded in 1950 as the result of the gift of French merchant Sir Antonin Besse of Aden, St Antony's specialises in international relations, economics, politics, and area studies relative to Europe, Russia, former Soviet states, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, Japan, China, and South and South East Asia.[1] It is consecutively ranked in the top five worldwide....

St Antony's reputation as a key centre for the study of Soviet affairs during the Cold War, led to rumours of links between the college and the British intelligence services; the author Leslie Woodhead wrote to this effect, describing the college as "a fitting gathering place for old spooks".....

As a postgraduate only college, St Antony's does not appear in the university's annual Norrington Table.

-- St Antony's College, Oxford, by Wikipedia.

At the end our retreat year in late May it was decided that we would visit the Promised Land, the site chosen for the enlightened society of either the near or far future, depending on whose story you listened to. The land that was chosen was Nova Scotia, Canada's Riviera. I was in favor of establishing enlightened society as soon as possible -- a year or two at the most. Others seemed to be dragging their feet.

Our Grieves and Hawks uniforms from London were ordered but would not be ready in time for the trip. So I contacted a military surplus company in New York which I had located through their advertisement in Shotgun News. I ordered one dark blue naval uniform for Rinpoche and an army khaki uniform for myself. Onto these uniforms I sewed two bars of medal ribbons that Rinpoche had designed. On my uniform I sewed my Rupon of the Red Division insignia. "Rupon'' was Tibetan for a company commander, which was the rank I then held. "Major" was pushing it a bit. Next to that ribbon I added the Iron Wheel medal and the Lion of Kalapa Court of Shambhala. This was jumping the gun somewhat because the Kalapa Court, which was to be located in Boulder, Colorado, had not yet been established. At most there were rumors of a house on Pine Street and an offer to purchase.

Sometime in the early light of morning Rinpoche, his consort, Jane, and I pored over the chart of the Province of Nova Scotia. It was to be a two-pronged attack. The Regent Osel Tendzin with his Group "B" would advance by air to Halifax Airport. The three of us in Group ''A" would go by sea, driving first to Portland and then taking the Nova Scotia Cruise Lines luxury ship up the coast. We would cross the Bay of Fundy to Yarmouth. The secrecy and stealth of our attack would surely take the natives by surprise. Finally, all of my training and reading of the Horatio Hornblower books would become useful information. Rinpoche would go as the Prince of Bhutan and I as his aide-de-camp, Major Perks, Lion of Kalapa. Jane would be Lady Jane, although I preferred to think of her as Lady Jane Gray. We were glad of our passports, which had our cover names of Chogyam Mukpo, John Perks, and Jane Condon.

The limousine that was rented for the ten-day operation was a silver Lincoln Continental. With great care I packed our evening dress tuxedos, as we planned to dine formally every night in the soon-to-be-enlightened province. We drove up to Portland, Maine, the next day to embark for the journey up the coast. Our limo was a bit oversized for the luxury liner, which looked more like a large ferry boat. After parking in the depths of its hull we found we could not open the rear doors more than six inches. Lady Jane could just squeeze through, but the Prince would never pass the gap. I pulled on his arms for a while until we realized the futility. Then the Horatio Hornblower in me became active. "The window!" I exclaimed. Lady Jane let down the rear electric window. The Prince put his arms around my neck and with Lady Jane holding up his pants we extricated him from the silver trap. On the ferry that morning, as the sun rose, the three of us stood on the upper deck and sang the Shambhala anthem. I threw an empty sake bottle overboard with a written copy of the anthem in it.

The Yarmouth dock smelled strongly of fish when we arrived and Rinpoche remarked that it reminded him of Tilopa. A good omen. We drove up to Halifax to meet the Regent's party and begin the expedition. (It had been named KOSFEF, short for Kingdom of Shambhala First Expeditionary Force. Later, there would be a medal ribbon for each member.) The Regent's force was already at the hotel I had chosen from the tourist brochure, the Horatio Nelson Hotel.

We had dressed in our uniforms earlier that morning on the boat, so we arrived at the hotel in style. Michael Root, the Regent's aide-de-camp, had arranged for the Shambhala flag we had hand sewn during retreat to be flown at the hotel entrance alongside the Canadian flag. Somehow I had it in my mind that there would be crowds attending our arrival. Instead, there was only the Regent's small party in their pinstriped suits and formal dresses. That evening we dined in our full evening dress at Fat Frank's, Halifax's only gourmet restaurant. There were speeches and toasts to the formation of enlightened society. We all sang the Shambhala anthem, with Fat Frank and his waiters joining in the end chorus, "Rejoice, the Great Eastern Sun arises."

I felt like the Kingdom had already happened, although Jerry, who was the Dapon, or Head of the Military, looked very glum. Michael and I talked to him on the way back to the hotel. "This is all crazy," he said. "Take over Nova Scotia? Make it Shambhala Kingdom? It's nuts!" This should have been my line, but somehow I had been overtaken by the fantasy. It all seemed real, quite easy, as I explained to Jerry in my enthusiasm. He was looking at me like I was crazy.

"You know," he complained, "you all come into the Nelson Hotel and salute Rinpoche who is pretending to be the Prince of Bhutan. You have that Shambhala flag flying next to the Canadian real flag in the front of the hotel. That's crazy! People will think we're all crazy!"

"Well," I argued, "Fat Frank and his waiters had a good time. Everyone seems quite friendly."

"You just can't come in here and take over," said Jerry.

"Why not?" asked Michael. "No one else seems to be in charge.

Jerry just shook his head. "I don't know. Taking over a Canadian province, making Rinpoche king and then calling it the Kingdom of Shambhala. Doesn't that seem a bit weird to you?"

"No," I replied. To cheer him up I pointed out the good omens: Tilopa at Yarmouth, letting us fly the flag at the hotel, and Fat Frank who wanted to be one of us and seemed to be convinced of our reality.

-- The Mahasiddha and His Idiot Servant, by John Riley Perks

But they had no money. So how was he going to have his own center? A mystery. But he sounded very confident about it, and he asked me would I like to be his private secretary. And I said yes.

So I stayed there for a week, and I met with him regularly on a one-to-one basis. And I think I had a different attitude toward him than the other people who were there, who were mostly connected through the Theravadin tradition. There had been a few Theravadin monks in London, so people had some connection with that. But the idea of having an actual guru was not most people’s approach. They were just coming, and he was like the monk in residence as far as they were concerned.

A High Leigh Summer School in the 1970s picture Hazel Waghorn (held at the Royal Agricultural University Cirencester, in the Cotswold Countryside)

-- The 90th Anniversary of The Buddhist Society 1924–2014, by The Buddhist Society

As far as I was concerned, he was the guru, because I had read this book that talked in those terms.

So at the end of the week, I went back to London. And a day or two afterwards I was having dinner – I was with my wife Jackie – and she said to me, “I have a feeling you don’t really need me anymore.” And I said, “Yeah, maybe you’re right.” And she said, “I’m going to be leaving you.” And I said, “What?” And I didn’t really say much about it. But when I woke up the next morning – we had this big king-size bed, and there was this big empty space next to me -- she was gone. And I was kind of surprised, although she had said that, because it was so sort of sudden. And I remember calling up Trungpa Rinpoche in Oxford and saying, “You’ll never guess what happened. My wife left me.” He said, “Oh, yes.” And I said, “I have the feeling that if I contacted her, and asked her to come back, she probably would.” And he said, “Well, I wouldn’t do that if I were you.” And I said, “No, I’m not going to.” [Laughing] So then I told him we had a very stormy kind of relationship.

And then he came up to London and stayed with me in the flat that we had. And then I asked if he would check up on her. She was working in a store. I knew where she was staying. So she was working in this store on Oxford Street, and we drove over there. And he went in and checked up on her. I showed him a photograph of her. And he came out and I said, “What do you think?” And he said, “She seems to be fine.” I said, “Okay.”

And then a couple of days later we set out for Scotland.