by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/26/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

7th General Conference

Date: 29 November - 4 December B.E. 2507 (1964)

Venue: Sarnath and Varanasi, India

Sarnath, Varanasi in India was chosen as the venue of the conference because it is where Śākyamuni delivered his first sermon which came to be known as the turning of the Wheel of the Law, the Dharmacakra. It was also as tribute to the Centenary of the birth of the late Venerable Anāgārika Dharmapāla who was the pioneer of the Buddhist revival in India and the first Buddhist missionary to visit Europe and America that spread Buddhism beyond Asia.

-- The World Fellowship of Buddhists (The WFB) [World Buddhist Conference], by http://wfbhq.org

Anagarika Dharmapāla

අනගාරික ධර්මපාල

Srimath Anagarika Dharmapāla

Born: 17 September 1864, Matara, Ceylon

Died: 29 April 1934 (aged 69), Sarnath, India

Nationality: Sinhalese

Other names: Don David Hewavitarane

Education: Christian College, Kotte; St Benedict's College, Kotahena; S. Thomas' College, Mutwal; Colombo Academy

Known for: Sri Lankan independence movement, revival of Buddhism,

Representing Buddhism in the Parliament of World Religions(1893) / Buddhist missionary work in three continents

Parent(s): Don Carolis Hewavitharana, Mallika Dharmagunawardhana

Anagārika Dharmapāla (Pali: Anagārika, [ɐˈnɐɡaːɽɪkɐ]; Sinhalese: Anagarika, lit., Sinhalese: අනගාරික ධර්මපාල; 17 September 1864 – 29 April 1934) was a Sri Lankan (Sinhalese) Buddhist revivalist and writer. He was the first global Buddhist missionary. He was one of the founding contributors of non-violent Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism and Buddhism. He was also a pioneer in the revival of Buddhism in India after it had been virtually extinct there for several centuries, and he was the first Buddhist in modern times to preach the Dharma in three continents: Asia, North America, and Europe. Along with Henry Steel Olcott and Helena Blavatsky, the creators of the Theosophical Society, he was a major reformer and revivalist of Sinhala Buddhism and an important figure in its western transmission. He also inspired a mass movement of South Indian Dalits including Tamils to embrace Buddhism, half a century before B. R. Ambedkar.[1] At the latter stages of his life, he entered the order of Buddhist monks as Venerable Sri Devamitta Dharmapala.[2]

Early life and education

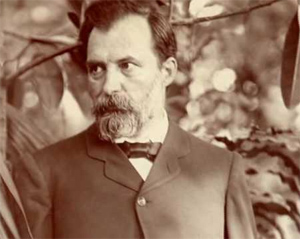

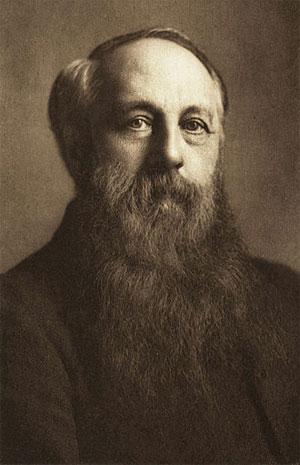

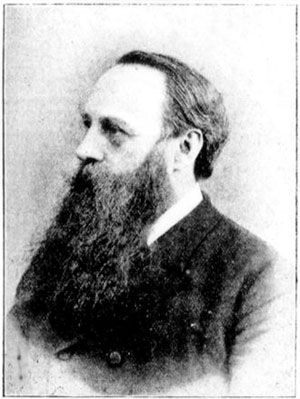

Srimath Anagarika Dharmapala at the age of 29 (1893)

Anagarika Dharmapala was born on 17 September 1864 in Matara, Ceylon to Don Carolis Hewavitharana of Hiththetiya, Matara and Mallika Dharmagunawardhana (the daughter of Andiris Perera Dharmagunawardhana), who were among the richest merchants of Ceylon at the time. He was named Don David Hewavitharane. His younger brothers were Dr Charles Alwis Hewavitharana and Edmund Hewavitarne. He attended Christian College, Kotte; St Benedict's College, Kotahena; S. Thomas' College, Mutwal[3][4] and the Colombo Academy (Royal College).

Buddhist revival

This was a time of Buddhist revival. In 1875 in New York City, Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott had founded the Theosophical Society. They were both very sympathetic to what they understood of Buddhism, and in 1880 they arrived in Ceylon, declared themselves to be Buddhists, and publicly took the Refuges and Precepts from a prominent Sinhalese bhikkhu. Colonel Olcott kept coming back to Ceylon and devoted himself there to the cause of Buddhist education, eventually setting up more than 300 Buddhist schools, some of which are still in existence. It was in this period that Hewavitarne changed his name to Anagarika Dharmapala.

'Dharmapāla' means 'protector of the dharma'. 'Anagārika' in Pāli means "homeless one". It is a midway status between monk and layperson. As such, he took the eight precepts (refrain from killing, stealing, sexual activity, wrong speech, intoxicating drinks and drugs, eating after noon, entertainments and fashionable attire, and luxurious beds) for life. These eight precepts were commonly taken by Ceylonese laypeople on observance days.[5] But for a person to take them for life was highly unusual. Dharmapala was the first anagarika – that is, a celibate, full-time worker for Buddhism – in modern times. It seems that he took a vow of celibacy at the age of eight and remained faithful to it all his life. Although he wore a yellow robe, it was not of the traditional bhikkhu pattern, and he did not shave his head. He felt that the observance of all the vinaya rules would get in the way of his work, especially as he flew around the world. Neither the title nor the office became popular, but in this role, he "was the model for lay activism in modernist Buddhism."[6] He is considered a bodhisattva in Sri Lanka.[7]

His trip to Bodh-Gaya was inspired by an 1885 visit there by Sir Edwin Arnold, author of The Light of Asia, who soon started advocating for the renovation of the site and its return to Buddhist care.[8][9] Arnold was directed towards this endeavour by Weligama Sri Sumangala Thera.[10][11]

At the invitation of Paul Carus, he returned to the U.S. in 1896, and again in 1902–04, where he traveled and taught widely.[12]

Dharmapala eventually broke with Olcott and the Theosophists because of Olcott's stance on universal religion. "One of the important factors in his rejection of theosophy centered on this issue of universalism; the price of Buddhism being assimilated into a non-Buddhist model of truth was ultimately too high for him."[13] Dharmapala stated that Theosophy was "only consolidating Krishna worship."[14] "To say that all religions have a common foundation only shows the ignorance of the speaker; Dharma alone is supreme to the Buddhist"[15]

Statue of Angarika Dharamapalan in Sarnath

At Sarnath in 1933 he was ordained a bhikkhu, and he died at Sarnath in December of the following year, aged 69.

Religious contribution

A Letter Written By Srimath Dharmapala in 23 June 1902 to a Friend in Japan.

The young Dharmapala helped Colonel Olcott in his work, particularly by acting as his translator. Dharmapala also became quite close to Madame Blavatsky, who advised him to study Pāli and to work for the good of humanity – which is what he did. It was at this time that he changed his name to Dharmapala (meaning "Guardian of the Dharma").

In 1891 Anagarika Dharmapala was on a pilgrimage to the recently restored Mahabodhi Temple, where Siddhartha Gautama – the Buddha – attained enlightenment at Bodh Gaya, India.[16] Here he experienced a shock to find the temple in the hands of a Saivite priest, the Buddha image transformed into a Hindu icon and Buddhists barred from worship. As a result, he began an agitation movement.[17]

The Maha Bodhi Society at Colombo was founded in 1891 but its offices were soon moved to Calcutta the following year in 1892. One of its primary aims was the restoration to Buddhist control of the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya, the chief of the four ancient Buddhist holy sites.[18][19] To accomplish this, Dharmapala initiated a lawsuit against the Brahmin priests who had held control of the site for centuries.[18][19] After a protracted struggle, this was successful only after Indian independence (1947) and sixteen years after Dharmapala's own death (1933), with the partial restoration of the site to the management of the Maha Bodhi Society in 1949. It was then the temple management of Bodh Gaya was entrusted to a committee comprised in equal numbers of Hindus and Buddhists.[18][19] A statue of Anagarika Dharmapala was established in College Square near Kolkata Maha Bodhi Society.[/b]

Anagarika on a 2014 stamp of India

Maha Bodhi Society centers were set up in many Indian cities, and this had the effect of raising Indian consciousness about Buddhism. Converts were made mostly among the educated, but also among some low caste Indians in the south.[20]

Due to the efforts of Dharmapala, the site of the Buddha's parinibbana (physical death) at Kushinagar has once again become a major attraction for Buddhists, as it was for many centuries previously. Mahabodhi Movement in 1890s held the Muslim Rule in India responsible for the decay of Buddhism in India.[16][21][22] Anagarika Dharmapala did not hesitate to lay the chief blame for the decline of Buddhism in India at the door of Muslim fanaticism.[23]

In 1893 Dharmapala was invited to attend the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago as a representative of "Southern Buddhism" – which was the term applied at that time to the Theravada. There he met Swami Vivekananda and got on very well with him. Like Swami Vivekananda, he was a great success at the Parliament and received a fair bit of media attention. By his early thirties he was already a global figure, continuing to travel and give lectures and establish viharas around the world during the next forty years. At the same time he concentrated on establishing schools and hospitals in Ceylon and building temples and viharas in India. Among the most important of the temples he built was one at Sarnath, where the Buddha first taught. On returning to India via Hawaii, he met Mary E. Foster, a descendant of King Kamehameha who had emotional problems. Dharmapala consoled her using Buddhist techniques; in return, she granted him an enormous donation of over one million rupees (over $2.7 million in 2010 dollars, but worth much more due to low labor costs in India). In 1897 he converted Miranda de Souza Canavarro who as "Sister Sanghamitta" came to establish a school in Ceylon.

Dharmapala's voluminous diaries have been published, and he also wrote some memoirs.

Dharmapala, science, and Protestant Buddhism

The term 'Protestant Buddhism,' coined by scholar Gananath Obeyesekere, is often applied to Dharmapala's form of Buddhism. It is Protestant in two ways. First, it is influenced by Protestant ideals such as freedom from religious institutions, freedom of conscience, and focus on individual interior experience. Second, it is in itself a protest against claims of Christian superiority, colonialism, and Christian missionary work aimed at weakening Buddhism. "Its salient characteristic is the importance it assigns to the laity."[24] It arose among the new, literate, middle class centered in Colombo.

The term 'Buddhist modernism' is used to describe forms of Buddhism that suited the modern world, usually influenced by European enlightenment thinking, and often adapted by Asian Buddhists as a counter to claims of European or Christian superiority. Buddhist modernists emphasize certain aspects of traditional Buddhism, while de-emphasizing others.[25] Some of the characteristics of Buddhist modernism are: importance of the laity as against the sangha; rationality and de-emphasis of supernatural and mythological aspects; consistency with (and anticipation of) modern science; emphasis on spontaneity, creativity, and intuition; democratic, anti-institutional character; emphasis on meditation over devotional and ceremonial actions.[25]

Dharmapala is an excellent example of an Asian Buddhist modernist, and perhaps the paradigmatic example of Protestant Buddhism. He was particularly concerned with presenting Buddhism as consistent with science, especially the theory of evolution.[26]

Survey of writings

Most of Dharmapala's works are collected in Return to Righteousness: A Collection of Speeches, Essays, and Letters of the Anagarika Dharmapala. (Edited by Ananda Guruge. Colombo: Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs, 1965).

The World's Debt to Buddha (1893)

Anagarika Dharmapala at the Parliament of World Religions. From left to right: Virchand Gandhi, Anagarika Dharmapala, Swami Vivekananda, and G. Bonet Maury.

This paper was read to a crowded session of the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago, 18 September 1893. At this early stage of his career, Dharmapala was concerned with making Buddhism palatable to his Western audience. This talk is full of references to science, the European Enlightenment, and Christianity. While presenting Buddhism in these familiar terms, he also hints that it is superior to any philosophy of the West. In addition, he spends considerable time discussing the ideal Buddhist polity under Ashoka and the Buddha's ethics for laypeople.

BUDDHA SHAKYAMUNI'S SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS

The basic teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni are well-known, so suffice it to . say, there is nothing in either the Four Noble Truths or the Holy Eightfold Path to suggest support for the use of violence, let alone warfare. On the contrary, two admonitions in the Holy Eightfold Path -"right action" and "right livelihood" - clearly indicate the very opposite.

Right action promotes moral, honorable, and peaceful conduct. It admonishes the believer to abstain from destroying life, from stealing, from dishonest dealings, and from illegitimate sexual intercourse. Instead, the believer should help others lead peaceful and honorable lives.

Right livelihood means that one should abstain from making one's living through a profession that brings harm to others, such as selling arms and lethal weapons, providing intoxicating drink or poisons, or soldiering, killing animals, or cheating. Instead, one should live in a way that does not cause harm or do injustice to others.

Together with right speech, right action and right livelihood form the basis for Buddhist ethical conduct. Underlying all Buddhist ethical conduct is a broad conception of universal love and compassion for all living beings, both human and nonhuman. Thus, based on these fundamental teachings of Shakyamuni, Buddhist adherents could in theory no more participate in that form of mass human slaughter known as "war" than they could purposely take the life of another. Yet ideals and practice often parted ways, as we will explore next.

LIFE OF THE BUDDHA

In accordance with the religious norms of his day, Shakyamuni offered advice on secular as well as purely spiritual matters. One example concerns a dispute that arose over the division of water from the drought-stricken Rohini River, which flowed between two kingdoms, one of them his own homeland of Kapilavastu. It is recorded that when the quarrel reached the point where a battle seemed imminent, Shakyamuni proceeded to the proposed battlefield and took his seat on the riverbank. He asked why the princes of the two kingdoms were assembled, and when informed that they were preparing for battle, he asked what the dispute was about. The princes said that they didn't know for sure, and they, in turn, asked the commander- in-chief. He also didn't know and sought information from the regent; and so the enquiry went on until it reached the husbandmen who related the whole affair. "What then is the value of water?" asked Shakyamuni. "It is but little," replied the princes. "And what of princes?" "It cannot be measured," they said. "Then would you," said Shakyamuni, "destroy that which is of the highest value for the sake of that which is worth little?" Reflecting on the wisdom of his words, the princes agreed to return peaceably to their homes.1

Another example of Shakyamuni's political intervention is said to have occurred in his seventy-ninth year, shortly before his death. King Ajatasattu of Magadha wished to make war on the tribal confederation of Vajji, so he sent an emissary to ask Shakyamuni what his chances of victory were. Shakyamuni declared that he himself had taught the Vajjians the conditions of true welfare, and as he was informed that the Vajjians were continuing to observe these conditions, he foretold that they would not be defeated. Upon hearing this, Ajatasattu abandoned his plan to attack.

Significantly, the first of the seven conditions Shakyamuni had taught the Vajjians was that they must "hold frequent public assemblies:' Secondly, they must "meet in concord, rise in concord, and act as they are supposed to do in concord."2 As a noted scholar pointed out, these conditions represent "a truly democratic approach," and "any society following these rules is likely to prosper and remain peaceful."3

A. L. Basham suggests that incidents like these demonstrate Shakyamuni's clear support for a republican form of government, though with the caveat that we are speaking of a form of governance in which there was an executive- sometimes elected, sometimes hereditary-supported by an assembly of heads of families that gathered periodically to make decisions relating to the common welfare.4 Restated in more contemporary terminology, Shakyamuni advocated a political model approaching a small-scale, direct -democracy,-though it is also clear that he did not-deny his counsel to the kings of the rising monarchies of his day.

Other elements of Shakyamuni's stance on violence are illustrated in the lead-up to an attack on his homeland by King Vidudabha of Kosala, the most powerful of the sixteen major kingdoms of his time. Shakyamuni recognized that this time the nature of the feud was such that his words would not be heeded, and he did not attempt to intervene. But even when the very existence of his homeland was at stake, Shakyamuni, his warrior background notwithstanding, refused to take up arms in its defense.

Shakyamuni's teaching on warfare and violence is perhaps best clarified in the Dhammapada, a Pali canonical work. In chapter 1, stanza 1, for example, Shakyamuni states: "For never does hatred cease by hatred here below: hatred ceases by love; this is an eternal law." And again, in chapter 15, stanza 201: "Victory breeds hatred, for the conquered is unhappy. The person who has given up both victory and defeat, that person, contented, is happy." In chapter 10, stanza 129, he says: ''All persons tremble at being harmed, all persons fear death; remembering that you are like unto them, neither strike nor slay." And finally, in chapter 8, stanza 103: "If someone conquers in battle a thousand times a thousand enemies, and if another conquers himself, that person is the greatest of conquerors."5 While scholars doubt these admonitions came directly from Shakyamuni's lips, the admonitions are, nevertheless, entirely consistent with his earliest and most fundamental teachings.

Two further aspects of Shakyamuni's teachings are worthy of mention. First, he was concerned about what we would today call social justice. For example, in the Pali Cakkavattisihanada Sutta of the Digha Nikaya (no. 26), Shakyamuni clearly identified poverty as the cause of violence and other social ills:As a result of goods not being accrued to those who are destitute, poverty becomes rife. From poverty becoming rife, stealing, ... violence, ... murder, ... lying, ... evil speech, ... adultery, ... incest, till finally lack of respect for parents, filial love, religious piety and lack of regard for the ruler will result.

Likewise, in the Kutadanta Sutta of the same Nikaya (no. 5), Shakyamuni praised a king named Mahavijita who, faced with an upsurge of robbery in his impoverished kingdom, provided his subjects with the economic means to improve their lives rather than imprisoning and executing the wrongdoers.6

THE EARLY BUDDHIST SANGHA AND THE STATE

Also important is the political or social dimension of the religious organization that Buddha Shakyamuni founded, the Sangha, that is, the community of monks and nuns (organized separately) dedicated to practicing his teachings. Primarily religious in nature, it embodied his concept of an ideal society.

The Sangha was based on noncoercive, nonauthoritarian principles by which leadership was acquired through superior moral character and spiritual insight, and monastic affairs were managed by a general meeting of the monks (or nuns). Unlike a modern business meeting, however, all decisions required the unanimous consent of those assembled. When differences could not be settled, a committee of elders was charged with finding satisfactory solutions.

Ideally, the Sangha was to be an organization that had no political ambitions and in whose ranks there was no striving for leadership. It sought by example and exhortation to persuade men and women to follow its way, not by force. Further, by his completely eliminating the then-prevalent caste system from its ranks, Shakyamuni may rightly be considered one of recorded history's first leaders to practice his belief in the basic equality of all human beings. He clearly hoped that the religious and social ideals of the Sangha would one day permeate the whole of society. This said, the historical subordination of the female Sangha to the male Sangha, through the imposition of eight additional precepts for nuns, betrays the ideal of human equality and points to the existence of a sexist attitude that may date back to Shakyamuni himself.

It is also true that even during the Buddha's lifetime, his Sangha became a wealthy landowner, though the lands referred to were held as the communal property of the various monastic communities.7 The lands themselves had all been donated by the faithful, initially kings, princes, and rich merchants. This raises the question as to what the donors expected of the Sangha in return for their material support. The classic answer is that they expected to acquire "merit," that spiritual reward that promises rebirth in a blessed state to all those who perform good deeds. As one Pali sutra relates, however, the accumulation of merit by the laity can also lead to the more immediate and mundane goals of "long life, fame, heavenly fortune, and sovereign power [italics mine]."8 The fact that King Ajatasattu also looked to Buddha Shakyamuni to forecast the likelihood of his victory against the Vajjians is significant here. Significant, in that it was already widely believed in ancient India that accomplished "holy men" possessed superhuman powers, including the ability to foresee the future.

Related questions are what effect the Sangha's collective possession of ever-greater amounts of land had on its own conduct, and equally important, whether as a major landholder it could fail in its actions and pronouncements to escape the notice and concern of state rulers. Would it be surprising to learn that these rulers also expected something in return for their material support of the Sangha, something approaching a moral endorsement of their rule, or the acquisition of merit, or the utilization of the supposed superhuman powers of Buddhist priests (and sutras) to protect the state from its enemies or ensure victory in battle?

KING ASHOKA-THE "IDEAL" BUDDHIST RULER?

If in the long run the Sangha willingly provided rulers with a moral endorsement, that endorsement was initially given only on the basis that rulers fulfill certain prerequisites or conditions. These conditions were contained in the Jataka stories, five hundred Indian folk tales that had been given a Buddhist didactic purpose and were incorporated into the Pali Buddhist canon sometime before the beginning of the Christian era. Among these tales we find a description of the "Ten Duties of the King," which include, among other things, the requirement that rulers abstain from anything that involves violence and destruction of life. Rulers are further exhorted to be free from selfishness, hatred, and falsehood, and to be ready to give up all personal comfort, reputation, fame, and even their very life if need be to promote the welfare of the people. Furthermore, it was the responsibility of kings to provide (1) grain and other facilities for agriculture to farmers and cultivators, (2) capital for traders and those engaged in business, and (3) adequate wages for those who were employed. When people are provided with sufficient income, they will be contented and have no fear or anxiety. Consequently, their countries will be peaceful and free from crime.9

It was, of course, one thing to present kingly duties in the abstract and another to find kings who actually practiced them. Buddhists discovered one such ruler in the person of King Ashoka (ca. 269-32 B.C.E.), who already controlled much of India at the time of his accession to the throne. Prior to converting to Buddhism, Ashoka is said to have engaged in wars of expansion until the bloodiness of his conquest of the kingdom of Kalinga caused him to repent and become a Buddhist layman, forswearing the use of violence. He then embarked upon a "Reign of Dharma" in which he advocated such moral precepts as nonharming, respect for all religious teachers, and noncovetousness.

In addition to renouncing aggressive warfare, Ashoka is said to have urged moderation in spending and accumulation of wealth, kind treatment of servants and slaves, cessation of animal sacrifices for religious purposes, and various other maxims, all carved as inscriptions and royal edicts on cliff faces and stone pillars throughout his vast realm, which extended almost the entire length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent. Further, he appointed officers known as Superintendents of Dharma for the propagation of religion, and arranged for regular preaching tours. Realizing the effectiveness of exhortation over legislation, he is said to have preached the Dharma on occasion. Ashoka become the archetypal Buddhist ruler, an ideal or Universal Monarch (see chapter 7).

As opposed to this idealized portrait, Indian historian A. L. Basham has pointed to another side of King Ashoka. For example, Ashoka maintained an army and used force against tribal groups that clashed with his empire. Beyond that, one Buddhist description of his life, the Sanskrit Ashokavandana, records that he ordered eighteen thousand non-Buddhist adherents, probably Jains, executed because of a minor insult to Buddhism on the part of single one. On another occasion, he forced a Jain follower and his entire family into their house before having it burnt to the ground. He also maintained the death penalty for criminals, including his own wife, Tisyaraksit whom he executed. In light of these and similar acts, we can say that Ashoka was an archetypal "defender of the faith" who was not averse to the use of violence.

Nor did King Ashoka's remorse at having killed over 100,000 inhabitants of Kalinga lead him to restore its freedom or that of any other of his earlier conquests. Instead, he continued to govern them all as an integral part of hi empire, for "he by no means gave up his imperial ambitions."10 In fact, inasmuch as many of his edicts mention only support for Dharma, (a pan-Indian politico-religious term) and not the Buddha Dharma, it is possible to argue that he used Dharma not so much out of allegiance to the Buddhist faith and its ideals, but as a means to centralize power, maintain unity among his disparate peoples, and promote law and order throughout the empire.

At the very least, in promoting Buddhism throughout India, Ashoka Was clearly also promoting his own kingship and establishing himself.11 That is to say, an alliance of politics and religion had been born. This is important to note because while Ashoka may have been the first to use Buddhism and the (Buddha) Dharma for what we would today identify as political purposes, he was hardly the last, as we shall see shortly when we examine the development of Buddhism in China and Japan.

A noted Indian political philosopher, Vishwanath Prasad Varma, pointed out that due to King Ashoka's royal patronage, "the Sangha became contaminated with regal and aristocratic affiliations."12 Similarly, the pioneer Buddhist scholar T. W. Rhys Davids remarked that it was the Sangha's close affiliation with King Ashoka that was "the first step on the downward path of Buddhism, the first step on its expulsion from India."13

What is certain is that Ashoka enjoyed a great deal of power over the Sangha. For example, a second Buddhist record of Ashoka's life, the Pali Mahavamsa, states that Ashoka was, with the aid of the great elder Moggaliputta Tissa, responsible for defrocking sixty thousand Sangha members who were found to harbor "false views."14 Ashoka had the power to prescribe passages from the sutras that Sangha members were required to study. Those who failed to do so could be defrocked by his officers.15 In fact, it became necessary to receive Ashoka's permission even to enter the priesthood.16 In short, during Ashoka's reign, if not before, the Raja Dharma (Law of the Sovereign) became deeply involved in, if not yet in full command of, the Buddha Dharma. This too was a harbinger of things to come.

In this connection, both Basham and Rhys Davids identified the concept of a so-called Universal Monarch, or Cakravartin (Wheel-Turning King), as coming into prominence within Buddhist circles only after the reign of Ashoka's father, Candragupta, who ascended the throne sometime at the end of the fourth century B.C.E,17 Thus, the idea of a Universal Monarch, who served as the protector of the Buddha Dharma and as the recipient of the Dharma's protection, did not originate as a teaching of Buddha Shakyamuni himself. Instead, it is best understood as a later accretion that "'was an inspiration to ambitious monarchs, ... some [of whom] claimed to be Universal Monarchs themselves."18 It is also significant that as a Universal Monarch and Dharma Protector, Ashoka was accorded the personal title of Dharma Raja (Dharma King), a title he shared with Buddha Shakyamuni,19 This "sharing of titles" would play an important role in China.

-- Chapter 12: Was it Buddhism?, Zen at War, Second Edition, by Brian Daizen Victoria

The Constructive Optimism of Buddhism (1915)

Buddhism was often portrayed in the West, especially by Christian missionaries, as pessimistic, nihilistic, and passive. One of Dharmapala's main concerns was to counter such claims, and this concern is especially evident in this essay.

Message of the Buddha (1925)

In the later stages of his career, Dharmapala's vociferous anti-Christian tone is more evident. Dharmapala must be understood in the context of British colonization of Ceylon and the presence of Christian missionaries there. This work is a good example of "Protestant Buddhism," as described above.

Evolution from the Standpoint of Buddhism (1926)

Darwin's theory of evolution was the cutting edge of science during Dharmapala's life. As part of his attempt to show that Buddhism is consistent with modern science, he was especially concerned with evolution.

Contributions to Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalism

Dharmapala was one of the primary contributors to the Buddhist revival of the 19th century that led to the creation of Buddhist institutions to match those of the missionaries (schools, the YMBA, etc.), and to the independence movement of the 20th century. DeVotta characterizes his rhetoric as having four main points: "(i) Praise – for Buddhism and the Sinhalese culture; (ii) Blame – on the British imperialists, those who worked for them including Christians; (iii) Fear – that Buddhism in Sri Lanka was threatened with extinction; and (iv) Hope – for a rejuvenated Sinhalese Buddhist ascendancy" (78). He illustrated the first three points in a public speech:

This bright, beautiful island was made into a Paradise by the Aryan Sinhalese before its destruction was brought about by the barbaric vandals. Its people did not know irreligion ... Christianity and polytheism [i.e. Hinduism] are responsible for the vulgar practices of killing animals, stealing, prostitution, licentiousness, lying and drunkenness ... The ancient, historic, refined people, under the diabolism of vicious paganism, introduced by the British administrators, are now declining slowly away.[27]

He once praised the normal Tamil vadai seller for his courage and blamed the Sinhalese people who were lazy and called upon them to rise. He strongly protested against the killing of cattle and eating of beef. In short, Dharmapala's reasons for rejecting British imperialism were not political or economic. They were religious: above all, the Sinhala nation is the historical custodian of Buddhism.[citation needed]

One of the manifestation of the new intolerance took place in 1915 against some Ceylonese Muslims. Successful retail traders became the target of their Shinhala competitors.[28] In 1912 Darmapala wrote:

The Muhammedans, an alien people, ... by shylockian methods become prosperous like Jews. The Sinhala sons of the soil, whose ancestors for 2358 years had shed rivers of blood to keep the country free of alien invaders ... are in the eyes of the British only vagabonds. The Alien South Indian Muhammedan come to Ceylon, sees the neglected villager, without any experience in trade ... and the result is that the Muhammedan thrives and the sons of the soil go to the wall.[29]

In short, Dharmapala and his associates very much encouraged and contributed to something aptly called the "ethnocratic state."[28]

Dharmapala believed that Sinhalese are a pure Aryan race with unmixed blood. He claimed that Sinhalese women must take care and to avoid Mischling with minority races of the country.[30] According to Ranga Jayasuriya of news paper Daily Mirror, Anagarika Darmapala exploited liberal leanings of the Colonial British to espouse his border line racism. Jayasuriya also states that Dharmapala would not have survived had it been the French, the Dutch, Belgian or any other colonizer.[31]

Legacy

In 2014, India and Sri Lanka issued postage stamps to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Dharmapala.[32] In Colombo, a road has been named in his honour as "Anagarika Dharmapala Mawatha" (Angarika Dharmapala Street).[33][34]

See also

• Buddhism and Theosophy

• Humanistic Buddhism

• Neo-Vedanta

• Walisinghe Harischandra

References

1. ^ "Taking the Dhamma to the Dalits". The Sunday Times. Sri Lanka. 14 September 2014.

2. ^ Epasinghe, Premasara (19 September 2013). "The Dharmapala legacy". Daily News. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

3. ^ Anagarika Dharmapala – a noble son of Sri Lanka Archived25 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

4. ^ Anagarika Dharmapala :The patriot who propagated Buddhism Archived 3 July 2013 at Archive.today

5. ^ Harvey, p. 208.

6. ^ Harvey, p. 205

7. ^ McMahan, p. 291.

8. ^ Harvey, p. 303

9. ^ Maha Bodhi Society: Founders

10. ^ India Revisited by Sri Edwin Arnold Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

11. ^ Barua, Dipak Kumar (1981). Buddha Gaya Temple: Its History. Buddha Gaya Temple Management Committee.

12. ^ Harvey, p. 307

13. ^ McMahan, p. 111

14. ^ Prothero, p. 167.

15. ^ Prothero, p. 172

16. ^ :a b The Maha-Bodhi By Maha Bodhi Society, Calcutta (page 205)

17. ^ O'Reilly, Sean and O'Reilly, James (2000) Pilgrimage: Adventures of the Spirit, Travelers' Tales. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-885211-56-9.

18. ^ :a b c Wright, Arnold (1999) Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources, "Angarika Dharmapala", Asian Educational Services. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-206-1335-5

19. ^ :a b c Bleeker, C. J. and Widengren, G. (1971) Historia Religionum, Volume 2 Religions of the Present: Handbook for the History of Religions, Brill Academic Publishers. p. 453. ISBN 978-90-04-02598-1

20. ^ Harvey, p. 297

21. ^ "A Close View of Encounter between British Burma and British Bengal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

22. ^ The Maha-Bodhi By Maha Bodhi Society, Calcutta (page 58)

23. ^ Wadia, Ardeshir Ruttonji (1958). The Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi: And Other Essays Philosophical and Sociological. University of Mysore. p. 483.

24. ^ Gombrich, Richard F. (1988). Theravada Buddhism; A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul. p. 174. ISBN 978-0415365093

25. ^ :a b McMahan, pp. 4–5

26. ^ McMahan, pp. 91–97

27. ^ Dharmapala, Anagarika (1965). Return to Righteousness: A Collection of Speeches, Essays, and Letters of the Anagarika Dharmapala. Anagarika Dharmapala Birth Centenary Committee, Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs, Ceylon. p. 482.

28. ^ :a b Little, David (1994). Sri Lanka: The Invention of Enmity. United States Institute of Peace Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-878379-15-3.

29. ^ Jayawardena, Kumari (1985). Ethnic and Class Conflicts in Sri Lanka: Some Aspects of Sinhala Buddhist Consciousness Over the Past 100 Years. Centre for Social Analysis. pp. 27–29.

30. ^ Sunil, Wijesiriwardhana (2010) Purawasi Manpeth. FLICT. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-955-1534-16-5

31. ^ Wimal Weerawansa's free-fall from grace. Daily Mirror, Sri Lanka. 4 April 2017

32. ^ "India, Sri Lanka issue stamp in honour". The Sunday times. 21 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

33. ^ "Dharmapala Mawatha (Colombo)". WikiMapia. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

34. ^ "Brown's Road (Anagarika Dharmapala Mawatha)". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

Cited sources

• Harvey, Peter (1990). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History, and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521313339.

• McMahan, David L. (2009). The making of Buddhist modernism. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-518327-6.

• Prothero, Stephen R. (1996). The white Buddhist: the Asian odyssey of Henry Steel Olcott. Indiana University Press.

Sources

• Trevithick, Alan (2006). The revival of Buddhist pilgrimage at Bodh Gaya (1811–1949): Anagarika Dharmapala and the Mahabodhi Temple. ISBN 978-81-208-3107-0.

• Anagarika Dharmapala Archive at Vipassana Fellowship

• WWW Virtual Library: ANAGARIKA DHARMAPALA at http://www.lankalibrary.com

• Anagarika Dharmapala, The Arya Dharma – Free eBook

• DeVotta, Neil. "The Utilisation of Religio-Linguistic Identities by the Sinhalese and Bengalis: Towards General Explanation". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, Vol. 39, No. 1 (March 2001), pp. 66–95.

• Ven. Kiribathgoda Gnanananda Thero, 'Budu Sasuna Bebala Wu Asahaya Dharma Duthayano', Divaina, 17 September 2008

• Sangharakshita, Flame in Darkness: The Life and Sayings of Anagarika Dharmapala, Triratna Grantha Mala, Poona 1995

• Sangharakshita, Anagarika Dharmapala, a Biographical Sketch, and other Maha Bodhi Writings, Ibis Publications, 2013

• Daya Sirisena, 'Anagarika Dharmapala – trail-blazing servant of the Buddha', Daily News, 17 September 2004

• Anagarika Dharmapala A religio-cultural hero

• Bartholomeusz, Tessa J. 1993. "Dharmapala at Chicago : Mahayana Buddhist or Sinhala Chauvinist?" Museum of Faiths. Atlanta : Scholars Pr. 235–250.

• Kloppenborg, Ria. 1992. "The Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933) and the Puritan Pattern". Nederlands Theologisch Tijdschrift, 46:4, 277–283.

• McMahan, David L. 2008. The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 91–97, 110–113.

• Obeyesekere, Gananath 1976. "Personal Identity and Cultural Crisis : the Case of Anagārika Dharmapala of Sri Lanka."Biographical Process. The Hague : Mouton. 221–252.

• Prothero, Stephen. 1996a. "Henry Steel Olcott, Anagarika Dharmapala and the Maha Bodhi Society." Theosophical History, 6:3, 96–106.

• Prothero, Stephen. 1996b. The White Buddhist: The Asian Odyssey of Henry Steel Olcott. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

• Saroja, G V. 1992. "The Contribution of Anagarika Devamitta Dharmapāla to the Revival of Buddhism in India." Buddhist Themes in Modern Indian Literature, Madras : Inst. of Asian Studies. 27–38.

• Amunugama, Sarath, 2016 " The Lion's Roar: Anagarika Dharmapala & the Making of Modern Buddhism" Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications.