Robert Charles Zaehner

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/13/19

List of Spalding Professors

Holders of the Spalding Chair to date have been:

• 1936 to 1952: Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

• 1952 to 1974: R. C. Zaehner

• 1976 to 1991: Bimal Krishna Matilal

• 1992 to 2015: Alexis Sanderson

• 2016 to present: Diwakar Nath Acharya[3]

-- Spalding Professor of Eastern Religion and Ethics, by Wikipeida

Light, and the enlightenment it brings, is to be welcomed from whatever source it comes. Spalding and Henderson acknowledged that many lamps light the path to truth. The religions of India, China, and Japan promise deliverance from darkness to light. Hinduism promises deliverance from ignorance of the real to knowledge of the real, furnishing the seeker after truth with a strategic and a progressive plan of salvation. Siddharta Gautama, the Buddha, with his gospel of liberation from the suffering and the dis-ease of existence, is the exemplary 'enlightened one' -- as his title reveals. In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, light illuminates the path to wholeness, well-being, and salvation. Each of these religions, in its distinctive and particular way, satisfies a universal human need. Does any one religion take precedence over the others? Can any one religion contain the truth for everyone and for all time? It was one thing for Spalding and Henderson to assert -- at a time when it was less common to do so than it is today -- that there are many different ways in which spiritual insight and wisdom is to be attained. This they did, ex animo, but neither man was ever to be a campaigner for a new universal system of beliefs (whether reformed but 'secular', or reformed and 'religious') based upon the abandonment of doctrinal particularity. This point is worth making if only to refute the charge laid against both men (but especially against HN by Professor R. C. Zaehner during the course of his inaugural lecture in Oxford) that their interest in world religions concealed an attempt to use the study of comparative religion in order to promote a universal syncretism. This, quite simply, was not true of either Spalding or Henderson.44.....

Who was to succeed Radhakrishnan after his sixteen years of tenure of the professorship? The election to the Chair in 1952 demonstrated that Oxford was not prepared to allow the benefactor's personal wishes to influence the decision about who the new Professor was to be. HN's main purpose in founding the Chair had never been to promote the study of 'Comparative Religion' as a discrete academic subject for an intellectual elite. He wanted people in the West to be informed about Eastern religions in general, and about Hinduism and Buddhism in particular. For this purpose he was convinced that the exposition of these religious systems by a competent Asian scholar was likely to be more authentic than that given by someone born and educated in the West, however able a research scholar that person might be. In a memorandum written in 1953 after his disillusionment with the decision taken by the electors to appoint R. C. Zaehner to the vacant Chair, Spalding recapitulated some of the reasons why he established it. He noted that in any study of 'the Great Religions' Hinduism, Buddhism will 'have a peculiarly important place; for they developed perhaps the greatest religious philosophy and mystical systems in the world'.These have been powerfully developed by the great Commentators. From the Bhagavad-Gita onward till today they have given rise to successive devotional movements. They are the source of two of the greatest epics in the world, of dramas and lyrics, of sculpture and painting. In short, these two great related cultures vie with that of Greece itself. It was with these wider studies in view that my wife and I founded the Chair of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford. We did not in terms restrict it to the teaching of these two cultures, or even to a scholar of Asian descent; we trusted to the Electors (unfortunately in vain) to carry out the intentions of the Chair. The Preamble makes them clear:

It is a condition of the Gift that the purpose of the professorship shall be to build up in the University of Oxford a permanent interest in the great religions and ethical systems (alike in their individual, social, and political aspects) of the East, whether expressed in philosophic, poetic, devotional, or other literature, in art, history, and in social life and structure, to set forth their development and spiritual meaning, and to interpret them by comparison and contrast with each other and with the religions and ethics of the West and in any other appropriate way, with the aim of bringing together the world's great religions in closer understanding, harmony, and friendship; as well as to promote co-operation with other Universities, bodies, and persona, in East and West which pursue the like ends, which purpose is likely to be furthered by the establishment of a Professorship, which would in the natural course normally be held by persons of Asian descent.' [23]

Growing Disillusionment

It was clear that in normal circumstances -- by which he meant the availability and readiness of a suitably qualified candidate -- HN expected the holder of the Chair to be an Asian. This had been acknowledged by the University from the outset, when provision for 'normal tenure by a person of Asian descent was substituted at the suggestion of the University for an original draft which precluded Europeans from appointment'. The importance and significance of the Preamble was recognized by the inclusion of extracts from it in a footnote to the Statutes. If it were found necessary to appoint a European in the absence of a suitable Asian candidate, the successful European candidate would not expect to hold the Chair permanently. HN recognised (and even hoped) that an Asian candidate, who could 'rely upon returning from Oxford with enhanced prestige to preferment in his own country', would in any case find a short-term professorship more congenial than a European. Things came to a head in 1952 when the electors met to choose a successor to Radhakrishnan. On this occasion they did not choose an Asian. They chose R. C. Zaehner. Spalding was infuriated that an 'unsuitable' candidate had been chosen to fill the post instead. A lasting rift with the University ensued, as a result of which HN decreed that the University was to receive no further grants from the Spalding Trust. He expressed his displeasure in the following terms.The election of a highly unsuitable candidate (a philologist, a Christian, and a European) to the Chair of Eastern Religions and Ethics having been arranged without consultation with its Founders, and in the teeth of their own wish for a highly suitable Hindu philosopher, and of the intention and provision of the Statute, no further benefactions are to be made to or in the University of Oxford until these abuses and their cause have been remedied. [24]

The election of R. C. Zaehner was perceived by HN as a repudiation of his ideas and ideals in founding the Chair. Zaehner's inaugural lecture entitled Foolishness to the Greeks, was given before the University of Oxford on 2 November 1953, only a few weeks after HN's death. In retrospect it is easy to understand why some of Zaehner's remarks on that occasion gave such lasting offence to the members of Spalding's family who were in the audience. Parts of the lecture were perceived by them and others to constitute a gratuitous insult to HN's memory. The ensuing rift between Zaehner and the Spalding Trust was not to be healed.

_______________

44. The charge against Spalding, the founder of the Chair to which Zaehner had just been elected, was made in the new Professor's inaugural lecture, 'Foolishness to the Greeks', to an audience which included H and his wife. Zaehner also used the occasion to make the same criticism of his predecessor, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. The ensuing hostility between HN and Zaehner, which arose not only as a result of Spalding's objection to Zaehner's election but out of the latter's declaration of intent to change the emphasis of the work of the Chait, is considered in chapter four, pp. 114ff.

-- The Spalding Trust and the Union for the Study of the Great Religions: H.N. Spalding's Pioneering Vision, by Edward Hulmes

R. C. Zaehner (1972)

Robert Charles Zaehner (1913–1974) was a British academic whose field of study was Eastern religions. He could read in the original language many sacred texts, e.g., Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic. Earlier, starting in World War II, he had served as an intelligence officer in Iran. At Oxford University his first writings had been on the Zoroastrian religion and its texts. Appointed Spalding Professor, his books addressed such subjects as mystical experience (articulating a comparative typology), Hinduism, comparative religion, Christianity and other religions, and ethics. He translated the Bhagavad-Gita, providing an extensive commentary based on Hindu tradition and sources. His last books addressed similar issues in popular culture, which led to his talks on the BBC. He published under the name R. C. Zaehner.[1][2]

Life and career

Early years

Born on 8 April 1913 in Sevenoaks, Kent, he was the son of Swiss–German immigrants to England. Zaehner "was bilingual in French and English from early childhood. He remained an excellent linguist all his life."[3][4] Educated at the nearby Tonbridge School, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford, where he studied Greek and Latin, and also ancient Persian including Avestan, gaining first class honours in Oriental Languages. During 1936–37 he studied Pahlavi, another ancient Iranian language, with Sir Harold Bailey at Cambridge University. Zaehner thereafter held Prof. Bailey in high esteem.[5] He then began work on his book Zurvan, a Zoroastrian Dilemma, a study of the pre-Islamic religion of Iran.[6][7]

Zaehner enjoyed "a prodigious gift for languages". He later acquired a reading knowledge of Sanskrit (for Hindu scriptures), Pali (for Buddhist), and Arabic (for Islamic).[8] In 1939 he taught as a research lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford. About this time, after reading the French poet Rimbaud, and in Rumi the Sufi poet of Iran, as well as study of the Hindu Upanishads, Zaehner came to adopt a personal brand of "nature mysticism". Yet his spiritual progression led him in the mid-1940s to convert to Christianity, becoming a Roman Catholic while stationed in Iran.[9]

British intelligence

During World War II starting in 1943, he served as a British intelligence officer at their Embassy in Tehran. Often he was stationed in the field among the mountain tribes of northern Iran. After the war he also performed a more diplomatic role at the Tehran embassy.[6][10] Decades later another British intelligence officer, Peter Wright, described his activities:

"I studied Zaehner's Personal File. He was responsible for MI6 counterintelligence in Persia during the war. It was difficult and dangerous work. The railway lines into Russia, carrying vital military supplies, were key targets for German sabotage. Zaehner was perfectly equipped for the job, speaking the local dialects fluently, and much of his time was spent undercover, operating in the murky and cutthroat world of countersabotage. By the end of the war his task was even more fraught. The Russians themselves were trying to gain control of the railway, and Zaehner had to work behind Russian lines, continuously at risk of betrayal and murder by pro-German or pro-Russian... ."[11]

continued in Iran until 1947 as press attaché in the British Embassy,[12] and as an MI6 officer. He then resumed his academic career at Oxford doing research on Zoroastrianism. During 1949, however, he was relocated to Malta where he trained anti-Communist Albanians. By 1950 he had secured an Oxford appointment as Lecturer in Persian literature. Again in 1951–1952 he returned to Iran for government service. Prof. Nancy Lambton, who had run British propaganda in Iran during the war, recommended him for the Embassy position. Journalist Christopher de Bellaigue describes Robin Zaehner as "a born networker who knew everyone who mattered in Tehran" with a taste for gin and opium. "When Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman, asked Zaehner at a cocktail party in Tehran what book he might read to enlarge his understanding of Iran, Zaehner suggested Alice through the Looking Glass."[13][14][15][16]

Zaehner publicly held the rank of Counsellor in the British Embassy in Tehran. In fact, he continued as an MI6 officer. During the Abadan Crisis he was assigned to prolong the Shah's royal hold on the Sun Throne against the republican challenge led by Mohammed Mossadegh, then the Prime Minister. The crisis involved the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company which had been in effect nationalised by Mossadegh. Zaehner thus became engaged in the failed 1951 British effort to topple the government of Iran and return oil production to that entity controlled by the British government.[17] "[T]he plot to overthrow Mossadegh and give the oilfields back to the AIOC was in the hands of a British diplomat called Robin Zaehner, later professor of Eastern religions at Oxford."[18][19][20] Such Anglo and later American interference in Iran, which eventually reinstalled the Shah, has been widely criticized.[21][22][23]

In the 1960s, MI5 counterintelligence officer Peter Wright questioned Zaehner about floating allegations that he had doubled as a spy for the Soviet Union, harming British intelligence operations in Iran and Albania during the period following World War II. Zaehner is described as "a small, wiry-looking man, clothed in the distracted charm of erudition." In his 1987 book Spycatcher Wright wrote that Zaehner's humble demeanor and candid denial convinced him that the Oxford don had remained loyal to Britain. Wright notes that "I felt like a heel" for confronting Zaehner.[24]

Although in the intelligence service for the benefit of his Government, on later reflection Zaehner did not understand the utilitarian activities he performed as being altogether ennobling. In such "Government service abroad", he wrote, "truth is seen as the last of the virtues and to lie comes to be a second nature. It was, then, with relief that I returned to academic life because, it seemed to me, if ever there was a profession concerned with a single-minded search for truth, it was the profession of the scholar."[25][26] Prof. Jeffrey Kripal discusses "Zaehner's extraordinary truth telling" which may appear "politically incorrect". The "too truthful professor" might be seen as "a redemptive or compensatory act" for "his earlier career in dissimulation and deception" as a spy.[27][28]

Oxford professor

University work

Before the war Zaehner had lectured at Oxford University. Returning to Christ Church several years after the war, he continued work on his Zurvan book,[29] and lectured in Persian literature. His reputation then "rested on articles on Zoroastrianism, mainly philological" written before the war.[30]

In 1952 Zaehner was elected Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics to succeed the celebrated professor Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who had resigned to become Vice-President (later President) of India.[31][32][33] Zaehner had applied for this position. Radhakrishnan previously had been advancing a harmonizing viewpoint with regard to the study of comparative religions, and the academic Chair had a subtext of being "founded to propagate a kind of universalism". Zaehner's inaugural lecture was unconventional in content. He delivered a strong yet witty criticism of "universalism" in religion.[34]

It drew controversy. Prof. Michael Dummett opines that what concerned Zaehner was "to make it clear from the start of his tenure of the Chair that he was nobody else's man."[35][36] Zaehner continued an interest in Zoroastrian studies, publishing his Zurvan book and two others on the subject during the 1950s.[37]

Since 1952, however, he had turned his primary attention further East. "After my election to the Spalding Chair, I decided to devote myself mainly to the study of Indian religions in accordance with the founder's wishes."[38] He served Oxford in this academic chair, while also a fellow at All Souls College, until his death in 1974, and never married.[6][39]

In his influential 1957 book Mysticism Sacred and Profane, Zaehner discussed this traditional, cross-cultural spiritual practice. Based on mystical writings, he offered an innovative typology that became widely discussed in academic journals. He also analyzed claims that mescalin use fit into this spiritual quest. His conclusion was near dismissive. Yet he revisited his harsh words on the naïveté of drug mysticism in his 1972 book Zen, Drug and Mysticism. His warnings became somewhat qualified by some prudent suggestions. He carefully distinguished between drug-induced states and religious mysticism. Then the BBC began asking him to talk on the radio, where he acquired a following. He was invited abroad to lecture.[40][41]

His delivery in Scotland of the Gifford Lectures led him to write perhaps his most magisterial book. Zaehner traveled twice to the University of St. Andrews during the years 1967 to 1969. The subject he choose concerned the convoluted and intertwined history of the different world religions during the long duration of their mutual co-existence. He described the interactions as both fiercely contested and relatively cross-cultivating, in contrast to other periods of a more sovereign isolation. The lectures were later published in 1970 "just four years before his death" by Oxford University as Concordant Discord. The interdependence of faiths.[42][43]

Peer descriptions

As professor Zaehner "had a great facility for writing, and an enormous appetite for work. [He also] had a talent for friendship, a deep affection for a number of particular close friends and an appreciation of human personality, especially for anything bizarre or eccentric". Nonetheless. "he passed a great deal of his time alone, most of it in his study working."[44]

An American professor described Zaehner in a different light: "The small, birdlike Zaehner, whose rheumy, color-faded eyes darted about in a clay colored face, misted blue from the smoke of Gauloises cigarettes, could be fearsome indeed. He was a volatile figure, worthy of the best steel of his age."[45]

His colleague in Iran, Prof. Ann K. S. Lambton of SOAS, recalled, "He did not, perhaps, suffer fools gladly, but for the serious student he would take immense pains". Prof. Zaehner was "an entertaining companion" with "many wildly funny" stories, "a man of great originality, not to say eccentricity."[46]

"Zaehner was a scholar who turned into something different, something more important than a scholar," according to Michael Dummett, a professor of philosophy at Oxford, who wanted to call him a "penseur" [French: a thinker]. With insight and learning (and his war-time experience) Zaehner shed light on key issues in contemporary spiritual life, writing abundantly. "His talent lay in seeing what to ask, rather than in how to answer... ."[47]

In theology he challenged the ecumenical trend that strove to somehow see a uniformity in all religions. He acted not out of an ill will, but from a conviction that any fruitful dialogue between religions must be based on a "pursuit of truth". If such profound dialogue rested on a false or a superficial "harmony and friendship" it would only foster hidden misunderstandings, Zaehner thought, which would ultimately result in a deepening mistrust.[48][49]

He died on 24 November 1974 in Oxford. "[A]t the age of sixty-one he fell down dead in the street on his way to Sunday evening Mass."[50]

His writings

Zoroastrian studies

Zurvan

Initially Zaehner's reputation rested on his studies of Zoroastrianism, at first articles mostly on philology in academic journals. He labored for many years on a scholarly work, his Zurvan, a Zoroastrian dilemma (1955). This book provides an original discussions of an influential theological deviation from the Zoroastrian orthodoxy of ancient Persia's Achaemenid Empire, which was a stark, ethical dualism. Zurvanism was promoted by the Sasanian Empire (224–651) which arose later during Roman times. Until the Muslim conquest, Zurvanism in the Persian world became established and disestablished by turns.[51][52][53]

Zurvan was an innovation analogous to Zoroastrian original doctrine. The prophet Zoroaster preached that the benevolent Ahura Mazda (the "Wise Lord"), as the creator God, fashioned both Spenta Mainyu (the Holy Spirit), and Angra Mainyu (the Aggressive Spirit) who chose to turn evil. These two created Spirits were called twins, one good, one evil. Over the centuries Ahura Mazda and his "messenger" the good Spenta Mainyu became conflated and identified; hence, the creator Ahura Mazda began to be seen as the twin of the evil Angra Mainyu. It was in this guise that Zoroastrianism became the state religion in Achaemenid Persia. Without fully abandoning dualism, some started to consider Zurvan (Time) as the underlying cause of both the benevolent Ahura Mazda and the evil Angra Mainyu. The picture is complicated by very different schools of Zurvanism, and contesting Zoroastrian sects. Also, Ahura Mazda was later known as Ohrmazd, and Angra Mainyu became Ahriman.[54][55][56][57]

Zurvan could be described as divinized Time (Zaman). With Time as 'father' twins came into being: the ethical, bountiful Ohrmazd, who was worshipped, and his satanic antagonist Ahriman, against whom believers fought. As Infinite Time, Zurvan rose supreme "above Ohrmazd and Ahriman" and stood "above good and evil". This aggravated the traditional 'orthodox' Zoroastrians (the Mazdean ethical dualists).[58][59] Zoroastrian cosmology understood that "finite Time comes into existence out of Infinite Time". During the 12,000 year period of finite Time (Zurvan being both kinds of Time), human history occurs, the fight against Ahriman starts, and the final victory of Ohrmazd is achieved. Yet throughout, orthodox Mazdeans insisted, it is Ohrmazd who remains supreme, not Zurvan. On the other hand, his adherents held that Zurvan was God of Time, Space, Wisdom, and Power, and the Lord of Death, of Order, and of Fate.[60]

Teachings of the Magi

The Teachings of the Magi (1956)[61] was Zaehner's second of three book on Zoroastrianism. It presented the "main tenets" of the religion in the Sasanid era, during the reign of Shapur II, a 4th-century King. Its chief sources were Pahlavi books written a few centuries later by Zoroastrians. Each of its ten chapters contains Zaehner's descriptive commentaries, illustrated by his translations from historic texts. Chapter IV, "The Necessity of Dualism" is typical, half being the author's narrative and half extracts from a Pahlavi work, here the Shikand Gumani Vazar by Mardan Farrukh.[62]

Dawn and Twilight

In his The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism (1961), Zaehner adopted a chronological dichotomy. He first explores origins, the founding of the religion by its prophet Zoroaster. He notes that the Gathas, the earliest texts in the Avesta, make it obvious that "Zoroaster met with very stiff opposition from the civil and ecclesiastical authorities when once he had proclaimed his mission." "His enemies... supported the ancient national religion." On moral and ecological grounds, Zoroaster favored the "settled pastoral and agricultural community" as against the "predatory, marauding tribal societies". His theological and ethical dualism advocated for "the followers of Truth the life-conserving and life-enhancing forces" and against the "destructive forces" of the Lie.[63] For the dates of the prophet's life, Zaehner adopted the traditional 6th century BCE dates.[64][65][66][67][68]

Zoroaster reformed the old polytheistic religion by making Ahura Mazdah [the Wise Lord] the Creator, the only God. An innovation by Zoroaster was the abstract notions, namely, the Holy Spirit, and the Amesha Spentas (Good Mind, Truth, Devotion, Dominion, Wholeness, Immortality). Zaehner interpreted them not as new substitutes for the excluded old gods, "but as part of the divine personality itself" which may also serve "as mediating functions between God and man". The Amesha Spentas are "aspects of God, but aspects in which man too can share."[69] Angra Mainyu was the dualistic evil.[70] Dating to before the final parting of ways of the Indo-Iranians, the Hindus had two classes of gods, the asuras (e.g., Varuna) and the devas (e.g., Indra). Later following the invasion of India the asuras sank to the rank of demon. Au contraire, in Iran the ahuras were favored, while the daevas fell and opposed truth, spurred in part by Zoroaster's reform. In the old Iranian religion, an ahura [lord] was concerned with "the right ordering of the cosmos".[71][72][73][74]

In Part II, Zaehner discussed the long decline of Zoroastrianism.[75] There arose the teachings about Zurvan i Akanarak [Infinite Time]. The Sasanid state's ideological rationale was sourced in Zoroastrian cosmology and sense of virtue. The Amesha Spentas provided spiritual support for human activities according to an articulated mean (e.g., "the just equipoise between excess and deficiency", Zoroastrian "law", and "wisdom or reason"). As an ethical principle the mean followed the contours of the 'treaty' between Ohrmazd [Ahura Mazda] and Ahriman [Angra Mainyu], which governed their struggle in Finite Time. Other doctrines came into prominence, such as those about the future saviour Saoshyans (Zoroaster himself or his posthumous son). Then after the final triumph of the Good Religion the wise lord Orhmazd "elevates the whole material creation into the spiritual order, and there the perfection that each created thing has as it issues from the hand of God is restored to it" in the Frashkart or "Making Excellent".[76][77][78]

Articles and chapters

Zaehner contributed other work regarding Zoroaster and the religion began in ancient Iran. The article "Zoroastrianism" was included in a double-columned book he edited, The Concise Encyclopedia of Living Faiths, first published in 1959.[79] Also were his several articles on the persistence in popular culture of the former national religion, "Zoroastrian survivals in Iranian folklore".[80] Chapters, in whole or part, on Zoroastrianism appeared in a few of his other books: At Sundry Times (1958), aka The Comparison of Religions (1962);[81] The Convergent Spirit, aka Matter and Spirit (1963);[82] and Concordant Discord (1970).[83]

Comparative religion

A choice of perspective

In the west the academic field of comparative religion at its origins inherited an 'enlightenment' ideal of an objective, value-neutral rationalism. Yet traditional Christian and Jewish writings provided much of the source material, as did classical literature, these being eventually joined by non-western religious texts, then empirical ethnological studies.[84][85] The privileged 'enlightenment' orientation in practice fell short of being value-neutral, and itself became progressively contested.[86] As to value-neutral, Zaehner situated himself roughly as follows:

"Any man with any convictions at all is liable to be influenced by them even when he tries to adopt an entirely objective approach; but let him recognize this from the outset and guard against it. If he does this, he will at least be less liable to deceive himself and others." "Of the books I have written some are intended to be objective; others, quite frankly, are not." "In all my writings on comparative religion my aim has been increasingly to show that there is a coherent pattern in religious history. For me the centre of coherence can only be Christ." Yet "I have rejected as irrelevant to my theme almost everything that would find a natural place in a theological seminary, that is, Christian theology, modern theology in particular." "For what, then, do I have sympathy, you may well ask. Quite simply, for the 'great religions' both of East and West, expressed... in those texts that each religion holds most sacred and in the impact that these have caused."[87][88][89]

Accordingly, for his primary orientation Zaehner chose from among the active participants: Christianity in its Catholic manifestation. Yet the academic Zaehner also employed a type of comparative analysis, e.g., often drawing on Zoroastrian or Hindu, or Jewish or Islamic views for contrast, for insight. Often he combined comparison with a default 'modernist' critique, which included psychology or cultural evolution.[90][91] Zaehner's later works are informed by Vatican II (1962-1965) and tempered by Nostra aetate.[92]

At Sundry Times [Comparison]

In his 1958 book At Sundry Times. An essay in the comparison of religions,[93]</ref> Zaehner came to grips with "the problem of how a Christian should regard the non-Christian religions and how, if at all, he could correlate them into his own" (p.9 [Preface]). It includes an Introduction (1), followed by chapters on Hinduism (2), on Hinduism and Buddhism (3), on "Prophets outside Israel", i.e., Zoroastrianism and Islam (4), and a concluding Appendix which compares and contrasts the "Quran and Christ". Perhaps the key chapter is "Consummatum Est" (5), which "shows, or tries to show, how the main trend in [mystical] Hinduism and Buddhism on the one hand and of [the prophetic] Zoroastrianism on the other meet and complete each other in the Christian revelation" (p.9, words in brackets added).

The book opens with a discussion of comparative religion. He cites Rudolph Otto (1869-1937) and al-Ghazali (1058-1111) as being skeptical of a writer with no religious experience who expounds on the subject. Yet Zaehner acknowledges that many Christians may only be familiar with their own type of religion (similar to Judaism and Islam), and thus be ill-equipped to adequately comprehend Hindu or Buddhist mysticism (pp. 12-15). Zaehner then compared the Old Testament and the Buddha, the former being a history of God's commandments delivered by his prophets to the Jewish people and their struggle to live accordingly, and the later being a teacher of a path derived from his own experience, which leads to a spiritual enlightenment without God and apart from historical events (pp. 15-19, 24-26). Needed is a way to bridge this gap between the two (pp. 15, 19, 26, 28). The gap is further illustrated as it relates to desire and suffering (p.21), body and soul (pp. 22-23), personality and death (pp. 23-24).

Christianity & other Religions

The 1964 book,[94] following its introduction, has four parts: India, China and Japan, Islam, and The Catholic Church. Throughout Zaehner offers connections between the self-understanding of 'other religions' and that of the Judeo-Christian, e.g., the Upanishads and Thomas Merton (pp. 25–26), Taoism and Adam (p. 68), Sunyata and Plato (p. 96), Al-Ghazali and St. Paul (p. 119-120), Samkhya and Martin Buber (pp. 131–132).

In the introduction, Zaehner laments the "very checkered history" of the Church. Yet he expresses his admiration of Pope John (1881-1963), who advanced the dignity that all humanity possesses "in the sight of God". Zaehner then presents a brief history of Christianity in world context. The Church "rejoiced to build into herself whatever in Paganism she found compatible" with the revelation and ministry of Jesus. Her confidence was inferred in the words of Gamaliel (pp. 7-9).[95] While Europe has known of Jesus for twenty centuries, 'further' Asia has only for three. Jesus, however, seemed to have arrived there with conquerors from across the sea, and "not as the suffering servant" (p.9).[96] As to the ancient traditions of Asia, Christians did "condemn outright what [they had] not first learnt to understand" (pp. 11, 13). Zaehner thus sets the stage for a modern review of ancient traditions.

"The Catholic Church" chapter starts by celebrating its inclusiveness. Zaehner quotes Cardinal Newman praising the early Church's absorption of classical Mediterranean virtues (a source some term 'heathen').[97] For "from the beginning the Moral Governor of the world has scattered the seeds of truth far and wide... ."[98] There may be some danger for Christians to study the spiritual truths of other religions, but it is found in scripture.[99]

Zaehner counsels that the reader not "neglect the witness" of Hinduism and Buddhism, as they teach inner truths which, among Christians, have withered and faded since the one-sided Reformation. The Church perpetually struggles to keep to a "perfect yet precarious balance between the transcendent... Judge and King and the indwelling Christ". Writing in 1964, Zaehner perceived "a change for the better" in the increasing acceptance of the "Yogin in India or Zen in Japan". Nonetheless, a danger exists for the 'unwary soul' who in exploring other religions may pass beyond the fear of God. Then one may enter the subtleties of mystical experience, and "mistake his own soul for God." Such an error in distinguishing between timeless states can lead to ego inflation, spiritual vanity, and barrenness.[100][101][102] [under construction]

Zaehner offers this categorical analysis of some major religious affiliations: a) action-oriented, worldly (Judaism, Islam, Protestantism, Confucianism); b) contemplation-oriented, other-worldly (Hinduism, Theravada Buddhism, Taoism); c) in-between (Mahayana Buddhism, neo-Confucianism, the reformed Hinduism of Gandhi, the Catholic Church).[103]

Comparative mysticism

Zaehner wrote extensively on comparative religion.[104] His interest turned to focus primarily on Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam. In his comparative work he directly addressed mysticism. Zaehner criticized the apparently simplistic idea, then widely endorsed: the mystical unity of all religions. He based his contrary views on well-known texts authored by the mystics of various traditions. After describing of their first-hand experiences of visionary states, he presented traditional interpretations. These might understand it as evidencing a particular world view, e.g., theism, monism, pantheism, or atheism.[105]

His critique challenged the thesis of Richard Bucke, developed in his 1901 book, Cosmic Consciousness. Bucke describes lesser facilities, then this prized 'cosmic' state of mind. He presents fourteen exemplary people of history, as each reaching a somewhat similar realization: the plane of cosmic consciousness.[106] This perennial idea has been variously advanced by Aldous Huxley, by Frithjof Schuon, by Houston Smith. Zaehner does not dispute that spiritual visionaries reach a distinguishable level of awareness. Nor does he deny that a life sequence over time may lead to mystical experience: withdrawal, purgation, illumination. Instead, what Zaeher suggests is a profound difference between, e.g., the pantheistic vision of a nature mystic, admittedly pleasant and wholesome, and the personal union of a theist with the Divine lover of humankind.[107][108][109]

Mystical experience

Mysticism as an academic field of study is relatively recent, emerging from earlier works with a religious and literary accent. From reading the writings of mystics, various traditional distinctions have been further elaborated, such as its psychological nature and its social-cultural context. Discussions have also articulated its phenomenology as a personal experience versus how it has been interpreted by the mystic or by others.[110] Professor Zaehner made his contributions, e.g., to its comparative analysis and its typology.

Sacred and Profane

[Under construction]

Hindu and Muslim

His innovative book compares the mystical literature and practice of Hindus and Muslims. He frames it with a theme of diversity.[111] On experiential foundations, Zaehner then commences to explore the spiritual treasures left to us by the mystics of the Santana Dharma, and of the Sufi tariqas. Often he offers a phenomenological description of the reported experiences, after which he interprets them in various theological terms.[112]

Zaehner describes five different types of mysticism to be found in Indian tradition: "the sacrificial, the Upanishadic, the Yogic, the Buddhistic, and that of bhakti."[113][114] Zaehner here relies on Hindu mystics because of their relative freedom from creed or dogma. He leaves aside the first (of historic interest), and the fourth (due to contending definitions of nirvana), so that as exemplars of mystical experience he presents:

• (a) the Upanishadic "I am this All" which can be subdivided into (i) a theistic interpretation or (ii) a monistic;

• (b) the Yogic "unity" outside space and time, either (i) of the eternal monad of the mystic's own individual soul per the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali or (ii) of Brahman, the ground of the universe, per the advaita Vedanta of Sankara; and,

• (c) the Bhakti mysticism of love, according to the commentary on the Bhagavad Gita by Ramanuja.[115]

Typology of the mystics

The above-described typology of mystic practice was derived directly from Hinduism and its literature.

Zaehner's more general analysis of the full range of mystical experience resulted in a different typology. Here his schema reflects not only the phenomenology of the experience itself but also the subject's explanations of it.

• (1) Nature mysticism;

• (2) Monistic mysticism;

• (3) Theistic mysticism.[116]

An endemic problem with such an analytic typology is the elusive nature of the conscious experience during the mystical state, its shifting perspectives of subject/object, and the psychology of spiritual awareness itself. Zaehner's proposals necessarily suffer from these general difficulties.

Nature mystics

Nature mysticism chiefly describes a spontaneous oceanic feeling in which a person identifies with the cosmos. It also may include a drug-induced state of consciousness. Like Aldous Huxley,[117] he had taken mescalin, but Zaehner came to a different conclusion. In his 1957 book Mysticism. Sacred and Profane. An Inquiry into some Varieties of Praeternatural Experience. Included are descriptions of the author's experience with mescalin, Yet his primary aim is to uphold a distinction between an amoral monism on the one hand and theistic mysticism on the other. In part he relies on a personal experience recorded by Martin Buber.[118] Here and elsewhere, he thus sets himself against Huxley's adoption of the Perennial Philosophy, an idea seeded with future misunderstandings.[119][120][121]

Monistic, non-dualist

Zaehner here focused especially on Hindu forms of non-dualism, e.g., the varieties of Vedanta. [Under construction]

Theistic, Christian

According to Zaehner, Christianity and theistic religions offer the possibility of a sacred mystical union with an attentive creator God, whereas a strictly monistic approach instead leads to the self-unity experience of natural religion.[122][123] Yet Zaehner remained hopeful in the long run of an ever-increasing understanding between religions. "We have much to learn from Eastern religions, and we have much too to give them; but we are always in danger of forgetting the art of giving--of giving without strings... ."[124]

During the 1940s spent in Iran he returned to the Christian faith. Decades later he published The Catholic Church and World Religions (1964), expressly from that perspective. As an objective scholar, he drew on his acquired insights from this source to further his understanding of others. Zaehner "did not choose to write to convince others of the truth of his own faith," rather "to frame questions" was his usual purpose.[125]

Gender, soul & spirit

Zaehner's interest in the writings of the mystics led him to studying the nominal gender of the sacred being they described. Often this being was male, whether the mystic was a man or a woman. In Christianity the Church as a whole was described by many as the bride of Christ.

Zaehner evolved into a conservative believer, whose ethics and morals were founded on his Catholic faith. Accordingly, sexual activity is blessed within the context of marriage.[126] His sexual orientation during World War II was said to have been homosexual. During his later life, while a don at Oxford, he became wholly devoted to teaching and research, and abstained from sexual intercourse.[127][128]

[Under construction]

Hindu religious texts

His translations and the Hinduism book "made Zaehner one of the most important modern exponents of Hindu theological and philosophical doctrines... . The works on mysticism are more controversial though they established important distinctions in refusing to regard all mysticisms as the same," wrote Prof. Geoffrey Parrinder.[129] For Zaehner's Hindu and Muslim Mysticism (1960), and like analyses, see "Comparative Mysticism" section.

Hinduism

While an undergraduate at Christ Church in Oxford, Zaehner studied several Persian languages. He also taught himself a related language, Sanskrit, used to write the early Hindu sacred books. Decades later he was asked by OUP to author a volume on Hinduism. Unexpectedly Zaehner insisted on first reading in Sanscrit the Mahabharata, a very long epic.[130] More than an heroic age story of an ancient war, the Mahabharata gives us the foremost compendium on Hindu religion and way of life.[131]

The resulting treatise Hinduism (1962) is elegant, deep, and short. Zaehner discusses, among other things, the subtleties of dharma, and Yudhishthira, the son of Dharma, who became the King of righteousness (dharma raja). Yudhishthira is the elder of five brothers of the royal Pandava family, who leads one side in the war of the Mahabharata. Accordingly, he struggles to follow his conscience, to do the right thing, to avoid slaughter and bloodshed. Yet he finds that tradition and custom, and the Lord Krishna, are ready to allow the usual killing and mayhem of warfare.[132][133]

As explained in Hinduism, all his life Yudhishthira struggles to follow his conscience.[134] Yet when Yudhishthira participates in the battle of Kuruksetra, he is told by Krishna to state a "half truth" meant to deceive. Zaehner discusses: Yudhishthira and moksha (liberation), and karma; and Yudhishthira's troubles with warrior caste dharma.[135][136][137] In the last chapter, Yudhishthira 'returns' as Mahatma Gandhi.[138] Other chapters discuss the early literature of the Vedas, the deities, Bhakti devotional practices begun in medieval India, and the encounter with, and response to, modern Europeans.[139]

Yudhishthira

Zaehenr continued his discussion of Yudhishthira in a chapter of his book based on his 1967-1969 Gifford Lectures.[140][141] Zaehner finds analogies between the Mahabharata's Yudhishthira and the biblical Job. Yet their situations differed. Yudhishthira, although ascetic by nature, was a royal leader who had to directly face the conflicts of his society. His realm and his family suffered great misfortunes due to political conflict and war. Yet the divine Krishna evidently considered the war and the destructive duties of the warrior (the kshatriya dharma) acceptable. The wealthy householder Job, a faithful servant of his Deity, suffers severe family and personal reversals, due to Divine acquiescence. Each human being, both Job and Yudhishthira, is committed to following his righteous duty, acting in conforming to his conscience.[142][143]

When the family advisor Vidura reluctantly challenges him to play dice at Dhrtarastra's palace, "Yudhishthira believes it is against his moral code to decline a challenge."[144][145] Despite, or because of, his devotion to the law of dharma, Yudhishthira then "allowed himself be tricked into a game of dice." In contesting against very cunning and clever players, he gambles "his kingdom and family away." His wife becomes threatened with slavery.[146][147][148]

Even so, initially Yudhishthira with "holy indifference" tries to "defend traditional dharma" and like Job to "justify the ways of God in the eyes of men." Yet his disgraced wife Draupadi dramatically attacks Krishna for "playing with his creatures as children play with dolls." Although his wife escapes slavery, the bitter loss in the dice game is only a step in the sequence of seemingly divinely-directed events that led to a disastrous war, involving enormous slaughter. Although Yudhishthira is the King of Dharma, eventually he harshly criticizes the bloody duties of a warrior (the kshatriya dharma), duties imposed also on kings. Yudhishthira himself prefers the "constant virtues" mandated by the dharma of a brahmin. "Krishna represents the old order," interprets Zaehner, where "trickery and violence" hold "an honorable place".[149][150]

Translations

In his Hindu Scriptures (1966) Zaehner presents his translations of selected classical texts, the Rig-Veda, the Atharva-Veda, the Upanishads, and the entire, 80-page Bhagavad Gita. He discusses these writings in his short Introduction. A brief Glossary of Names is at the end.[151] "Zaehner's extraordinary command of the texts" wast widely admired by his academic peers.[152]

That year Zaehner published a more annotated edition of the Bhagavad Gita, a prized episode in the Mahabharata epic. Before the great battle, the Lord Krishna discusses with the Pandava brother Arjuna the enduring spiritual realities. Krishna "was not merely a local prince of no very great importance: he was God incarnate--the great God Vishnu who has taken on human flesh and blood." Provided after his translation, is Zaehner's long Commentary, drawn from the medieval sages Sankara and Ramanuja, ancient scriptures and epics, and modern scholars. His Introduction places the Gita within the context of the Mahabharata and of Hindu philosophy. Hindu religious teachings in the Gita are addressed in terms of the individual Self, material Nature, Liberation, and Deity. A useful Appendix is organized by main subject, and under each are "quoted in full" the relevant passages, giving chapter and verse.[153][154]

Sri Aurobindo

In his 1971 book Evolution in Religion, Zaehner discusses Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872–1950), a modern Hindu spiritual teacher, and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955), a French palaeontologist and Jesuit visionary.[155][156] Zaehner discusses each, and appraises their religious innovations.[157]

Aurobindo at age seven was sent to England for education, eventually studying western classics at Cambridge University. On his return to Bengal in India, he studied its ancient literature in Sanskrit. He later became a major political orator with a spiritual dimension, a prominent leader for Indian independence. Hence he was jailed. There in 1908 he had a religious experience. Relocating to the then French port of Pondicherry, he became a yogin and was eventually recognized as a Hindu sage. Sri Aurobindo's writings reinterpret the Hindu traditions.[158] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, later President of India, praised him.[159] "As a poet, philosopher, and mystic, Sri Aurobindo occupies a place of the highest eminence in the history of modern India."[160][161]

Aurobindo, Zaehner wrote, "could not accept the Vedanta in its classic non-dualist formulation, for he had come to accept Darwinism and Bergson's idea of creative evolution." If the One being was "totally static" as previously understood "then there could be no room for evolution, creativity, or development of any kind." Instead, as reported by Zaehner, Aurobindo considered that "the One though absolutely self sufficient unto itself, must also be the source... of progressive, evolutionary change." He found "the justification for his dynamic interpretation of the Vedanta in the Hindu Scriptures themselves, particularly in the Bhagavad-Gita."[162][163] According to Aurobindo, the aim of his new yoga was:

"[A] change in consciousness radical and complete" of no less a jump in "spiritual evolution" than "what took place when a mentalised being first appeared in a vital and material animal world." Regarding his new Integral Yoga: "The thing to be gained is the bringing in of a Power of Consciousness... not yet organized or active directly in earth-nature, ...but yet to be organized and made directly active."[164][165]

Aurobindo foresees that a Power of Consciousness will eventually work a collective transformation in human beings, making us then actually able to form and sustain societies of liberté, égalité, fraternité.[166] Adherents of Aurobindo's new Integral Yoga (Purna Yoga) would lead India to a spiritual awakening; they would facilitate an increasingly common soul-experience, in which each achieves a mystic union with the One. Each such gnosis would also be guided by the Power of Consciousness. In choosing to pursue the realization of such social self-understanding, India would hasten the natural evolution of humanity.[167][168] Hence furthering the conscious commitment everywhere, to collaborate with the hidden drive of creative evolution toward a spiritual advance, is high among the missions of Aurobindo's new 'Integral Yoga'.[169][170] "It must be remembered that there is Aurobindo the socialist and Aurobindo the mystic."[171]

Gifford lecture at St Andrew

Zaehner gave the Gifford Lectures in Scotland during the years 1967–1969. In these sessions he revisited the subject of comparative mysticism focusing on Hinduism, then discussed Taoist classics, Neo-Confucianism, and Zen. In the course of the discourse, he mentions occasionally a sophisticated view: how the different religions have provided a mutuality of nourishment, having almost unconsicouslly interpenetrated each other's beliefs. The historically obfuscated result is that neighbouring religions might develop the other's theological insights as their own, as well as employ the other's distinctions to accent, or explain, their own doctrines to themselves. Although Zaehner gives a suggestive commentary at the conjunction of living faiths, he respects that each remains distinct, unique. Zaehner allows the possibility of what he calls the convergence of faiths, or solidarity.[172][173]

Regarding the world religions Zaehner held, however, that we cannot use the occasional occurrence of an ironic syncretism among elites as a platform from which to leap to a unity within current religions. His rear-guard opinions conflicted with major academic trends then prevailing. "In these ecumenical days it is unfashionable to emphasize the difference between religions." Yet Zaehner remained skeptical, at the risk of alienating those in the ecumenical movement whose longing for a festival of conciliation caused them to overlook the stubborn divergence inherent in the momentum. "We must force nothing: we must not try to achieve a 'harmony' of religions at all costs when all we can yet see is a 'concordant discord'... . At this early stage of contact with the non-Christian religions, this surely is the most that we can hope for." His Gifford Lectures were published as Concordant Discord. The Interdependence of Faiths.[174]

Social ideology and ethics

[Under construction].[175]

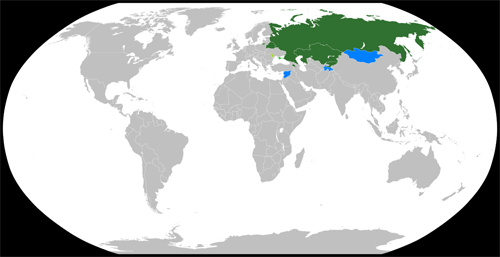

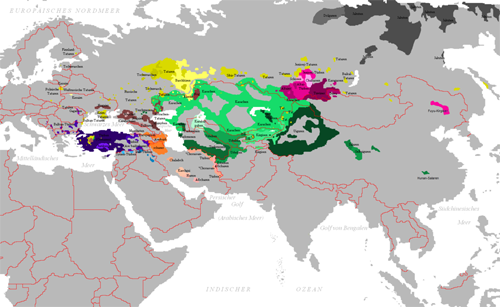

A militant state cult

Zaehner used a comparative-religion approach in his several discussions of Communism, both its quasi-philosophical theory (discussed below),[176] and here its practical control a sovereign state. Soviet party rule, in its ideological management political and economic operations, was said to demonstrate an attenuated resemblance to Catholic Church governance. Features in common included an authoritarian command structure (similar to the military), guided by an unquestionable theory or a dogma, which was articulated in abstract principles and exemplars.[177][178][179]

For the Marxist-Leninist the 'laws of nature' dominating political society were a complex dialectic involving class conflict.[180][181]

"Stalin saw, quite rightly, that since the laws of Nature manifested themselves in the tactical vicissitudes of day-to-day politics with no sort of clarity, even the most orthodox Marxists were bound to go astray. It was, therefore, necessary that some one man whose authority was absolute, should be found to pronounce ex cathedra what the correct reading of historical necessity was. Such a man he found in himself."[182][183]

A Soviet hierarchical system thus developed during the Stalinist era, which appeared to be a perverse copy of the organization of the Roman Catholic Church.[184][185] Yet Zaehner did not overlook the hideous, deadly, mass atrocities perpetrated, chiefly on its overworked citizenry during Stalin's rule.[186][187] He was, however, more interested in popular motivation, in the visionary import and quasi-religious dimension of Marx and Engels, than in machinations of the Leninist party's exercise of state power.[188][189][190]

Dialectical materialism

Communist ideology was analogized to various religious creeds. Here Zaehner took an interest in the materialist element in the Hegelian dialectic as developed by Marx and Engels. Zaehner compared the dynamics of matter with the role of the Spirit in the Christian concept of the Trinity, deriving various analogies.[191][192][193]

Engels had combined economic materialism, Darwinian evolution, and eastern mysticism into a systematic philosophy of dialectical materialism. Its Buddhist facet utilized "a religion without a personal God and even without a Hegelian Absolute."[194]

Cultural evolution

The interaction of natural science and social studies with traditional religions thought, particularly Christian, drew Zaehner's attention. Serving as a catalyst were the writings on evolution by Teilhard de Chardin. Juxtaposing a traditional biblical understanding of the spiritual conflicts of humankind, with a conjectured historical narrative of early human society, Zaehner would employ psychology and literature in an effort to craft a spiritual anthropolocy.[195]

Popular & drug culture

In his last three books, Zen, Drugs and Mysticism (1972), Our Savage God (1974), and City within the Heart (1981) [posthumous], Zaehner turned to address issues in contemporary society, drawing on his studies of comparative religion. He further explored the similarities and the differences between drug-induced experiences and traditional mysticism. As an academic he had already published several books on such issues starting in 1957.[196][197][198] In the meantime, a widespread counterculture had arisen, which included artists, rebels, and college youth. Their psychedelic experiences were often self-explained spiritually, with reference to zen and eastern mysticism.[199][200] Consequently, Zaehner wanted to reach this "wider public".[201] During the late 1960s he was "very often invited to talk on the BBC."[202]

Zaehner described various ancient quests to attain a mystical state of transcendence, of unification. Therein all contradictions and oppositions are reconciled; subject and object disappear, one passes beyond good and evil. That said, such a monist view can logically lead to excess, even to criminal acts.[203] If practiced under the guidance of traditional religious teachers, no harm usually results.[204][205][206] The potential for evil exists, however, through subtle misunderstanding or careless enthusiasm, according to Zaehner. After arriving at such a transcendent point, a troubled drug user may go wrong, feel licensed to do anything, with no moral limit. The misuse of a mystical state and its theology eventually can lead to horror.[207][208]

Zaehner warned of the misbehavior propagated by LSD advocate Timothy Leary,[209][210] the earlier satanism of Aleister Crowley, and ultimately the criminal depravity of Charles Manson.[211][212][213] His essay "Rot in the Clockwork Orange" further illustrates from popular culture the possible brutal effects of such moral confusion and license.[214] Yet Zaehner's detailed examination and review was not a witch hunt. His concluding appraisal of the LSD experience, although not without warning of its great risks and dangers, contained a limited, circumscribed allowance for use with a spiritual guide.[215][216]