Part 6 of 6

WORKING FOR THE CAUSEOn 26 September 1931 from the Hotel de Lutece; 17 avenue de Keyser, Antwerp, Mirsky wrote the last of his long series of letters to Suvchinsky. He said that he was there on political business, and that the business was in Brussels. This concerned the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Comintern: the next day Mirsky reports to Miss Galton that he had seen Palme Dutt in Brussels and would see him again. that day. Rajani Palme Dutt, the most important British person in the Comintern network, was based in Brussels from 1929 to 1936.91 Mirsky was no doubt directed to this meeting by the CPGB.

Once back in London, Mirsky began teaching as usual. Bernard Pares's account of subsequent events tries to maintain a dignified tone: 'While still with us, he attacked me violently in the press as a "mouth piece" of reaction. I took his political views as temperamental and did not reply. At the end of the next session he went off to Russia ..... '92 Towards the very end of 1931 there was an exchange of letters between Pares and Michael Florinsky. Pares wrote on 16 December:

The Mirsky affair has worked out as you expected. He wrote casually to me from abroad in the summer saying he was going on to a Soviet passport and asking me to arrange his visa at our Home Office. I had meanwhile read his 'Lenin' which, well as it is written, is evidently a most ex-parte statement. I replied saying the Home Office might ask me certain questions, for instance, was he prepared to abstain from agitating, while in England, for an overthrow of our system of government by force. This he did not answer in his reply, which was heated. On his return he refused to give the pledge mentioned above, but said he was leaving us at the end of this session, which he wished me to communicate to our Principal (of King's). This interview took place in Seton-Watson's presence. In view of his leaving we decided to take no further step: but since then he has not only done a lot of Communist propaganda here, but has now written a grossly perverted statement with regard to myself calling me 'one of the principal mouth-pieces of Anti-Soviet propaganda' and suggesting that I know nothing of Russia. He had earlier published a scurrilous invective against the 'Oxford and Cambridge blacklegs' who volunteered for public service during our General Strike, You might tell all this to Shotwell.93

Pares's recommendation that Florinsky denounce Mirsky to Shotwell probably indicates that Pares had got wind of Mirsky's tentative steps about finding himself a job in America. His further thoughts provide eloquent testimony about just how thin the field of Russian studies was in the English-speaking world in the early 1930s, and about the way appointments were arranged in those easygoing days:

It is all very unpleasant, but the main reason why I am writing is that there will anyhow be a vacancy on our staff next October if not earlier. My own Chair is supposed to cover 'Russian Language, Literature and History' and Mirsky does the literature. This gap must be filled, but it is not necessary that the scope of my Assistant should be defined in the same way as for him. The salary is £325. I am writing to one or two people to ask if they would like to be candidates, and that is why I am writing to you. I understand that your father was Professor of· Philology. What are your own record and studies in the field of Literature? We have a separate post for Comparative Slavonic Philology (held by Jopson, who is excellent). Could you more or less cover the literature (up to the standard of an Assistant Lecturer)? Were you appointed, I should of course welcome your cooperation in history. Have you at all followed current contemporary Russian Literature (in Moscow & abroad)? Don't understate things, but let me know -- if you would like to be a candidate -- how you stand in these matters and give me your full curriculum vitae with dates.

Florinsky politely declined Pares's invitation: 'I know nothing about philology, and I have never made any study of Russian literature except what one learns in a gimnaziya, which, as you know, is not much. I feel therefore that I would be a most inadequate substitute for Mirsky.' Florinsky is surely not the only person who has entertained the sentiment expressed in this last sentence.

HUGH MACDIARMIDThe 'Party work' Pares mentions consisted, at least in its public aspect in England, of speaking at rallies and writing for Communist publications. Mirsky contributed a series of articles to the Labour Monthly, which was edited by Palme Dutt. The first two appeared in 1931;94 two more appeared there in 1932.95 None of them is concerned with literature. The first of these articles has been recognized as the earliest authoritative presentation for the British Left of the current state of Dialectical Materialism in Soviet Russia after the 'Deborinite' ideological crisis of 1930.96 It found at least one appreciative reader in Antonio Gramsci, one of Mirsky's most illustrious Communist contemporaries. 97

In the autobiographical statement not for publication that he made in 1936 Mirsky claimed that he had spoken at about sixty meetings in various parts of England and-Ireland, mainly on behalf of the Friends of the Soviet Union.98 He is known to have spoken on behalf of the Friends of the Soviet Union and the Workers' Educational Association, in Manchester on 12 December 1931 16 January 1932; and in September 1932; in Edinburgh on 18 December 1931: in Glasgow in February 1932; and in Liverpool in March 1932.99 Vera Traill expressed the obvious view of what inevitably went on: 'He was a prince, and then he was a Russian- by origin, and when he gave Communist speeches at Communist meetings, someone in the crowd would always yell: "If you think it's so marvellous, why don't you go there to your country?"' Vera's version of the cry from the crowd, to which the unregenerate English mind irresistibly supplies a few expletives, was as manifestly unidiomatic as Mirsky's must have been when he gave these grotesque speeches.

At least one English proletarian did attribute to Mirsky a decisive role in the formation of his political views, though. One Sunday morning a certain David Wilson went for a long walk with Mirsky and bad his eyes opened to what he describes as the power of the bourgeois press to instil bourgeois opinion into the British proletariat, but their inability to create proletarian opinion. 100

The most prominent proletarian Mirsky knew at this time was a Scotsman Hugh MacDiarmid (Christopher Murray Grieve, 1892-1978).101 MacDiarmid was fond of using Russian sources, and he was dependent on translations into English; among his principal sources were the writings of Mirsky.102 Direct contact between MacDiarmid and Mirsky was. apparently made, by correspondence if not in person, after the Scotsman reviewed Modern Russian Literature103 and Contemporary Russian Literature. 104 MacDiarmid's admiration for Mirsky and solidarity with his political development as the 1920s drew to a close were expressed in his dedication of the programmatic First Hymn to Lenin (1931) to 'Prince D. S. Mirsky'. This dedication, which has appeared many times in the various republications of MacDiarmid's works, stands as the most enduring testament to the two men's affinities. In a return tribute which many fewer people can have noticed, Mirsky included an item by MacDiarmid in the anthology of modern English poetry which eventually appeared without his name after he was arrested. 105 These lines render into standard literary Russian three stanzas of 'The Seamless Garment', a Scots lyric addressed by MacDiarmid to a cousin who worked at the mill in their native town, Langholm. Eventually, one of MacDiarmid's major later works was dedicated, among others, to Prince Dmitry Mirsky,

A mighty master in all such matters

Of whom for all the instruction and encouragement he gave me

I am happy to subscribe myself here

The humble and most grateful pupil.106

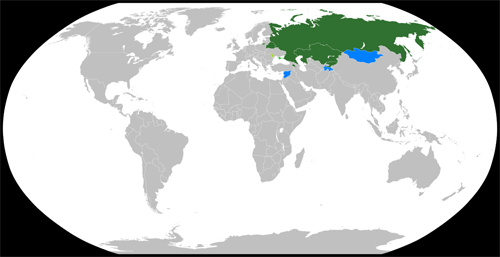

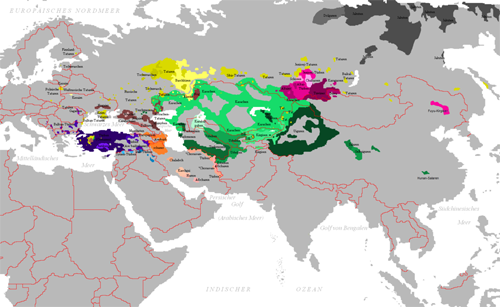

Mirsky and MacDiarmid were born at opposite ends of the social spectrum, but both came from border country, and both were on active service on foreign soil in the First World War; like most survivors of this conflict, they subsequently wondered what on earth they had been fighting for. In emigration, beginning with some of his earliest publications, Mirsky was involved in the agonized debate about the Russianness of the Russian Revolution;107 his involvement in the Eurasian movement revived this question. He conceived Russia: A Social History with a special emphasis on the nationalities question. In the book he wrote about the British intelligentsia soon after he returned to Russia, though, Mirsky makes no mention of nationalism as a significant element in their views.

Meanwhile, Hugh MacDiarmid was a founder member of the National Party of Scotland in 1928, but he was expelled from it because of his Communist sympathies in 1933. At some time in 1934 he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain.108 MacDiarmid's involvement with nationalist politics undoubtedly helps to account for Mirsky's reservation about his ideology in a Soviet encyclopedia article of 1933, and also the reference to the poet's 'idealism' in the anthology of 1937.109 The fact that, for publication in the anthology, Mirsky's translator turned MacDiarmid's Scots into standard Russian is a patent manifestation of the Great Russian chauvinism that was then becoming an important part of the ideology of Stalinism. Mirsky's standard English prose in his translation of a poem by Pushkin was turned into MacDiarmid's self-marginalizing Scots poem 'Why I Became a Scots Nationalist'; then his original Scots poetry about Lenin was translated into standard literary Russian, another language of imperial power.

Between the time he first read it and his arrest, Mirsky was probably too busy to think much about MacDiarmid; but between then and his death in the GULag, Mirsky had ample time to reflect on the now infamous stanza of the poem the Scotsman had dedicated to him in 1931:

As necessary, and insignificant, as death

Wi' a' its agonies in the cosmos still

The Cheka's horrors are in their degree;

And'll end suner! What maitters't wha we kill

To lessen that foulest murder that deprives

Maist men o' real lives?110

Mirsky, along with millions of others, certainly came to 'end suner'. The author of this poem, meanwhile, not being a Russian, had nearly fifty years of 'real' life left to reflect on whether or not all this mattered.

THE INTELLECTUAL LEFTAccording to some contemporaries, Mirsky's new-found Communism was fanatical. Beatrice Webb reports and then paraphrases his old friend Meyendorff's sad words (it is worth recalling the same man's assertion concerning Mirsky's erstwhile fanatical monarchism):

'We never meet now', for apparently he has a real admiration and liking for the talented and wayward Mirsky; he rejected Kingsley Martin's suggestion that Mirsky's conversion was not sincere -- it was all of a piece with his romantic career and his refusal as a young Guards officer to drink the health of the Tsar and consequent dismissal from his regiment. Indeed he said that Mirsky was a little mad and was becoming madder -- he feared that there might be some crisis. 111

Thirty years later, Kingsley Martin declared that 'Marxism, as understood in England, began with the destruction of the Labour Government in 1931 and ended with the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939. It was not an aberration of the Left Wing, but a deduction from the facts.' 112 This idea underlies the book Mirsky wrote about the British intelligentsia after he went back to Russia. In its penultimate chapter, dealing with the current state of British science, Mirsky asserts: 'From the autumn of 1931, in all British universities and in wide circles of the left intelligentsia, the study of dialectical materialism began.'113 The process, he says, was set in train by the political events of 1931, for scientists in particular by the publication of an English translation of Lenin's Materialism and Empiriocriticism, and also by. 'the arrival of a delegation from the USSR to the International Congress on the History of Science and Technology'.114 In the very last pages of the book Mirsky finds some hope for the future of Britain:

The interest in the U.S.S.R. is enormous and the interest in marxism is growing. In the course of the 1931-1932 academic year a number of clubs to the left of the reformists were founded. To-day there are, in the London School of Economics, The Marxist Society, in Oxford, The October Club, while in Cambridge the old Heretics now has a marxist leadership and a radically inclined membership. 115

Much of all this, Mirsky concedes, is transient and superficial, but 'everywhere there is healthy young growth; cadres are already forming'. We know with hindsight that certainly the most effective of these cadres, 'clear that civilisation to-day is inseparable from the task of proletarian revolution', were the ones whose commitment took the form of an agreement to work underground for the Soviets. The spectre of English Marxism has haunted the country ever since; the question of collaboration with the secret service raises a more substantial phantom.

The reference Mirsky makes in The Intelligentsia of Great Britain to the reformed Heretics Club in Cambridge is of particular interest. On Sunday, 22 November 1931 Mirsky lectured to the Heretics on Dialectical Materialism. Several eyewitnesses have described this event, with various degrees of hindsight. Esther Salaman set down her memory of it nearly half a century later:

We knew a good many people in the audience: Desmond Bernal and J. B. S. Haldane, in the front; behind us was Herbert Butterfield, the historian. Mirsky talked of 'the collapse of capitalism', the 'end of Western bourgeois civilisation' .... Now Mirsky was disinforming us; but I did not know at the time that he was driven by a desire to go back to Russia. Bernal got up and mumbled complete agreement on Dialectical Materialism. Butterfield asked some pointed questions ....

Salaman, who had grown up in Russia, listened with growing resentment. Eventually she blew up, and reproached Mirsky for daring to speak of the death of civilization in Cambridge, where so much pioneering work was going on in the natural sciences. It was, after all, at the Cavendish in 1932 that Rutherford's team discovered the neutron; Cockcroft split the atom at almost exactly the same time as Mirsky gave this talk, and Mirsky's compatriot Pyotr Kapitsa (1894-1984) was still working in the University.116 Mirsky, though, cheerfully admitted that he knew nothing at all about science. Salaman then

told Mirsky that the Bolsheviks had ruined 'our revolution': by introducing an alien philosophy to Russia. I had not forgotten our hope of a free Russia after the Revolution of 1917, which the Bolsheviks crushed by closing the Constituent Assembly and putting an armed guard outside when they found themselves in the minority. And the slogans! 'Dictatorship of the Proletariat' when there was no proletariat, 'Class war' when there were no classes in Marx's sense.

When there were no more questions Mirsky got up, and made his replies. At the end he said: 'As for the lady's criticism, it's not a matter for argument but for pistols .. .'117

Perhaps the most talented younger member of the CPGB in the early 1930s was the poet John Cornford (1915-36), the son of the Cambridge historian of ancient philosophy Francis and his poet wife, Frances. Frances Cornford wrote a letter to her son on Tuesday, 24 November 1931:

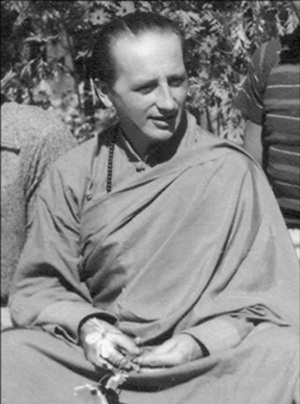

We went and heard Prince Mirsky last Sunday night on Dialectical Materialism-the philosophy of Communism. I longed for you to be there. Haldane tackling him. But Esther [Salaman] made much the best speech and Dadda asked much the best question, which really drew him. I'll have to tell you about it at length. Mirsky can't think much- -- ut he looks like a Byzantine Saint and he believes in Communism like a B. S. in the Trinity -- and his smile, when his ugly black-bearded face lights up with belief and hope, is one of the best things I've seen for ages. 118

This meeting of the Heretics was chaired by the distinguished Germanist Roy Pascal, who recalled it for me more than forty years later. He asserted that Mirsky's lecture was the first time that he and the other young Heretics who had recently radicalized the Club had heard about dialectical materialism from someone who seemed to know what he was talking about. Pascal was certain that Haldane and Bernal were present, also Maurice Cornforth and Hugh Sykes Davies, and probably also Joseph Needham and David Haden Guest. The moving spirit was Maurice Dobb. Pascal had met Mirsky before in Dobb's rooms in Cambridge, and thought he might have been to a talk on art or literature that Mirsky had given on a previous occasion, when Mirsky 'was very rough indeed to the traditional Cambridge approach to these problems, and he startled us very much with the brusque way in which he dismissed our attitudes, but he was always a very attractive person, a bit eccentric, with a strange whining in his voice whenever he stopped talking and so on, but very charming'.

Pascal took Mirsky as

really a man of ideas. You see, with this passion for culture, for ideas and so on, but very impractical, and I think very impractical about politics ... he wouldn't understand, but hardly anyone in England understood either ... however much one tried, one couldn't quite understand what the character of the Party was, and· what was the relationship between the Party (the Communist Party, of course) and the ideals which it represented or the proletariat that it represented and so on ...

The Party cell inside the university was founded by David Haden Guest soon after Mirsky's talk, in April 1932, and Maurice Dobb and J. D. Bernal were among its leading members. Similar cells came into being in the LSE in October 1931 and at University College London at about the same time; the three units made contact with each other in London at Easter 1932, and evolved a plan for coordinating student Communist activities throughout Britain.119 This was the situation when Mirsky returned to the USSR.

Mirsky's public speaking on behalf of Communist-front organizations continued. On 5 March 1932, the Morning Post reported that 'The activities of Prince Mirsky outside his work at King's College are such as to call for the attention of the public.'120 On 11 March, under the headline 'Mr D. S. Mirsky No Longer Connected with London University', the Morning Post carried the following notice:

It was stated at Kings College yesterday that Mr D. S. Mirsky, who had been a lecturer in the School of Slavonic Studies, had recently resigned -- although his contract was not due to expire until next July -- and that he was no longer connected with the College.

It will be recalled that on March 5 the 'Morning Post' called attention to the Communistic speeches that Mr Mirsky (who was formerly known as Prince Mirsky) had been making up and down the country.

After this unpatriotic activity in Great Britain, Mirsky spoke at two separate conferences in Amsterdam in 1932; the first took place in April.121 The second was held in late August, and is much better known; it is referred to variously as the 'Anti-War', 'Anti-Military', or 'Peace' Conference, a Comintern exercise masterminded by their propaganda wizard, Willi Munzenberg.122 The figureheads were billed as Gorky, Romain Rolland, and Henri Barbusse, and the proceedings opened on 27 August. The members of the Soviet delegation, headed by Gorky and Shvernik, were denied visas. This seems to have been the culminating point of Mirsky's involvement with the international Communist movement that was orchestrated by Palme Dutt in Brussels. 123

WHY MIRSKY WENT BACKIn a letter written on 22 June 1932 to Lady Ottoline Morrell, Virginia Woolf mentions that she must 'tomorrow dine with Mary Hutchinson and go to the Zoo; and on Monday have Mirsky and his prostitute, and on Tuesday dine with Americans ... '. Woolf's supercilious 'prostitute' refers, of course, to Vera Suvchinskaya.124 But for herself she noted, in her journal entry for this day:

So hot yesterday -- so hot, when Prince Mirsky came ... but Mirsky was trap mouthed: opened and bit his remark to pieces: has yellow misplaced teeth: wrinkles in his forehead: despair, suffering, very marked on his face. Has been in England, in boarding houses, for 12 years; now returns to Russia 'for ever'. I thought as I watched his eye brighten and fade -- soon there'll be a bullet through your head. That's one of the results of war, this trapped cabin'd man.125

One question is asked more often than any other about Mirsky's life, for obvious reasons. Why did he go back to Russia? If Virginia Woolf's perception is to be trusted, his decision to go had not brought Mirsky any serenity. Enough has been said so far about Mirsky's character to demonstrate that his actions were not seriously influenced by the drives that are conventionally reckoned to motivate men. He never seems to have done anything for the sake of power, for example, or fame actual or posthumous, or sexual passion--especially the final item in this list. 126 Janko Lavrin asserted, though, in all seriousness, a different sort of physical basis for Mirsky's actions:

Somebody told him -- or several people must have told him -- that his face was a replica of Lenin's face. It was so. And, d'you know, at first glance when you saw him, for the first time, you would have taken or mistaken him for Lenin; and he told me once: 'I'm very proud to resemble Lenin. He has made one of the greatest revolutions in history, and Russia is going to play an enormous part in world history now' .... This was in the 20s, long before those bloodbaths of Stalin and so on; he was quite seriously convinced that something enormous would come out of Russia ... If he was a Communist, he was a patriotic Communist, you know. Hoping, d'you know, for the very best as far as his own country was concerned.

The idea that Russian patriotism should lead to a commitment to the Soviet state was utterly inadmissible for Gleb Struve, and he postulated instead a purely psychological basis for Mirsky's actions, which he saw as irresponsible: 'To many people his conversion to Communism ... came as a surprise. But to some who knew him well this about-face seemed a natural result of his love of intellectual mischief and his instinctive nonconformism, and when in 1932 he went back to Russia, these people confidently predicted that he would end badly.'127[/quote]

The impressions of Lavrin and Struve concur in their implication that rather than by any of the usual considerations, Mirsky's actions were to an extraordinary degree driven by intellectual conviction. This conviction seems to have occupied the space usually shared to a greater or lesser extent by physical and emotional drives. Mirsky did many things for money, but only in order to have enough to supply his immediate needs; he seems to have had no interest in accumulating more. He denigrated his aristocratic origins, but he remained loyal to his parental family for as long as it lasted, and never seems to have wanted to start one of his own, preferring his 'boarding houses' to some alternative such as Virginia Woolf's childless and asexual arrangement. In his eyes, of course, it was she, not he, who was 'trapped, cabin'd' -- in English bourgeois society.

Mirsky did have a strong sense of his own dignity, though, and by the end of 1927 the life he was living must constantly have offended it. As a Russian emigre he was an embodiment of pitiable failure. As a Russian emigre prince he even embodied a standard caricature in the popular mythology of contemporary Western Europe. He had been teaching at the School of Slavonic Studies for five years, and although he had come across a small number of excellent individual students, his work in the classroom was demeaning for a man of his family tradition. He had published what he must have known to have been his best work, the two-volume history of Russian literature. This literature itself, the object of his study and teaching, seemed to be going into decline, and what promising talent did· exist was making itself felt in Soviet Russia rather than where he was, on the outside. Mirsky's own efforts to publish new Russian writing outside Russia had been an artistic success, but also an immense burden, because there were simply not enough readers to liberate the enterprise from dependence on private sponsors. The Eurasian movement seemed at first to offer some. possibility of genuine creative work, but it proved incapable of being moved on from what Mirsky saw as the pettifogging scruples of the old Russian intelligentsia. And the Eurasians' attempt to establish some sort of footing inside Russia was ignominious. Mirsky had lost his faith in the Orthodox Church and with it one of the central mainstays of Russia Outside Russia. He was accepted on equal terms by the literary elite of England and the other countries of Western Europe, and French cuisine was second to none, but given his character, how long could he have gone on with these pleasant distractions in this cultural wasteland that he considered 'done for'? He toyed with the idea of America, but his one expedition there boded ill. Above all, as someone who was never content to settle for what he had, Mirsky must have felt that he lacked a worthy purpose.

Meanwhile, Stalin was taking his country in hand. Russia had been restored to something closely approximating the borders of Mirsky's youth, when it was at the height of its prosperity and international weight. And it was setting itself up as the country that would lead the world towards the future. Russia was going somewhere. Its leader was the embodiment of that conscious will that Mirsky spoke about so often, while the rest of the world seemed to be going nowhere. And Mirsky's attitude was by no means an isolated case, to say the very least. Here is Hugh Dalton's rehearsal of a view that was commonplace among European intellectuals by the end of 1931:

There was no unemployment in the Soviet Union. Here was no 'industrial depression', no inescapable 'trade cycle', no limp surrender to 'the law of supply and demand'. Here was an increasing industrial upsurge, based on a planned Socialist economy. They had an agricultural problem, we knew, in the Soviet Union, but so had we in the capitalist West, where primary producers had been ruined by the industrial slump. We knew that in Soviet Russia there was no political freedom. But there never had been under the Russian Czars and, perhaps some of us thought, we had over-valued this in the West, relatively to the other freedoms. 128

Mirsky seems to have been able to live with the inescapable contradiction between Marxist determinism and godless post-Nietzschean willed forging of destiny. Though his knowledge of the rise of Stalinism was abstract., deriving almost entirely from his reading, Mirsky understood perfectly well what was actually going on in Russia. And he had no objection to it in principle, in fact quite the opposite: he had never believed in liberal democracy, with its 'paraphernalia', but instead he respected and argued the necessity for strong, even ruthless, leadership. Though he never explicitly worshipped 'necessary' cruelty to the extent that MacDiarmid and some other admirers of the USSR did, Mirsky evidently considered the inhumanity attendant on the introduction of a new order to be acceptable, and preferable to what he came to see as the protracted death of life under capitalism. Mirsky's disdain for Chekhov, which so many English people have found it so hard to forgive him, was partly based ·on stylistic grounds; but his most vehement objection was to what he called Chekhov's 'horrid contemptible humanitarianism, pity, contempt and squeamishness towards humankind, and not a single clever thought' .129 Having condemned Mayakovsky, who, though he had been on the side of the revolution all his conscious life, could not in the end put his and his generation's individualism behind him, Mirsky himself committed suicide, but suicide psychological rather than physical. He attempted to murder his individuality by committing himself to the service of the common cause, as some sort of disembodied agent of History. His return to Russia was the final expression, and also the abnegation, of that 'willed consciousness' he had spoken about so much in his writings about literature. He ended by surrendering his own will to Stalin's.

Some of the Russian intellectuals who stayed in Russia after 1917 did so because they wanted at least to represent the older values of their country in the face of the values of the new regime. Many emigres had left because they thought this cause hopeless, so that the national heritage had to be preserved and defended outside the geopolitical borders until such time as a new regime replaced the Bolsheviks. For Mirsky, though, his country always seems to have retained some supreme significance in and of itself;. he was a patriot in a way which is not to be confused with the maudlin nostalgia that was a persistent theme in Russian emigre writing, nor with the mystical messianism that was a common attitude among Russian intellectuals of his time. He always felt that what mattered most for his country was necessarily going on inside it, not outside it. He was born a Russian and brought up with the idea of service to his country, and his extraordinarily cosmopolitan education and his exposure to non-Russian societies reinforced rather than weakened his sense of national identity.

There is ample evidence that Mirsky's decision to go back was certainly not rash and impulsive, as has so often been said to be the case. He twisted and turned, considering several radical alternatives to Russia, chief among them a post in America or staying in England with Vera. It was the circumstances of twentieth-century political history, the crudely politicized view of loyalty that closed borders to 'undesirables' of all kinds, that meant that Mirsky's decision to go to Russia, once made, was irreversible; there was no possibility, for example, of making the maximum use of his abilities and coming and going between Russia and the West. Of his contemporaries, only Erenburg came near to achieving this balancing act, and it was done at a terrible cost in terms of personal integrity.

Mirsky's movements during the summer of 1932 can be traced from the postcards he regularly sent to Dorothy Galton in London. He indulged in his customary gastronomic tourism, for the last time. He left Paris for Gibraltar on 15 July, Vera Suvchinskaya taking the same ship from Marseilles. He said he was intending to be in the south of France by about 1 August. He sent another postcard from Seville on 23 July: 'Spain is really too sweet, I don't think I'll get out of it in a hurry. I am flying tomorrow to Madrid.' And again on 25 July: 'Seville is delightful ... I flew here, at a tremendous height all the time, about 5,000 feet I should say.' The last dated message to Miss Galton from Mirsky the emigre was dated 6 August 1932 and sent from the Hotel Melodia, par Le Levandou (Var): 'Vera and I are here till next Sunday (7th). On Thursday we shall be in Toulon. On Sunday we shall probably be going to Nice.' Mirsky sailed for Russia from either Le Havre or Marseilles, and arrived in Leningrad by ship in late September.

_______________

Notes:1. Cited in Veronika Losskaya, Marina Tsvetaeva v zhizni (Tenafly, 1989), 196.

2. Cited in G. S. Smith, The Letters of D. S. Mirsky to P. P. Suvchinskii (Birmingham, 1995), 2.

3. On Gorky's life, see Geir Kh'etso [Kjetsaa], Maksim Gorky: Surlba pisatelya (Moscow, 1997).

4. On Budberg, see Nina Berberova, Zheleznaya zhenshchina (New York, 1981).

5. M. Gor'ky i sovetskaya pechaat, ed. A. G. Dementiev et al. (2 vols., Moscow, 1964), i. 40 (Arkhiv M. Gorkogo, 10). By 'princely' Gorky probably means something like 'magnanimously hospitable'.

6. The Minerva was a boarding-house opposite Gorky's villa, run by one Signora Cacace. Her surname sounds to the Russian ear like a neologism meaning 'shittier', and it entered the language of Gorky and his circle; see Vladimir Khodasevich, 'Gor'ky', in Koleblemyi trenozhnik (Moscow, 1991), 358-60.

7. Gor'ky i sovetskie pisateli (Moscow, 1963), 602. The annotation to this letter (603) contains one of the very few references to Mirsky published in the USSR in the 40 years following his death, and gives his date of death as 1937.

8. 'The Literature of Bolshevik Russia', repr. in D. S. Mirsky, Uncollected Writings on Russian Literature, ed. G; S. Smith (Berkeley, Calif., 1989), 70. For a fuller discussion of Mirsky's published opinions of Gorky, see Ol' ga Kaznina and G. S. Smith, 'D. S. Mirsky to Maksim Gor'ky: Sixteen Letters (1928-1934)', Oxford Slavonic Papers n.s. 26 (1993), 87-92.

9. Khodasevich, Sobranie sochinenii (2 vols., Ann Arbor, Mich., 1983), ii. 535.

10. See Anastasiya Tsvetaeva, Vospominaniya, 3rd edn (Moscow, 1983). Tsvetaeva (1894-1993) remained in Moscow when her sister emigrated; she 'sat' in the GULag from 1937 for ten years, then in internal exile, and finally returned to Moscow in 1959.

11. Kamenev (1883-1936) was expelled from the Party as a Trotskyite in Dec. 1927, but readmitted after denouncing Trotsky the next year, only to be expelled again in 1934.

12. Kaznina and Smith, 'D. S. Mirsky to Maksim Gor'ky', 93.

13. 'The Story of a Liberation', in Mirsky, Uncollected Writings on Russian Literature, 364.

14. Clarence Augustus Manning (1893-1972) was Professor of Russian at Columbia University in Mirsky's time.

15. Malevsky-Malevich seems to have made his first address on behalf of the Eurasians in New York on 2 Jan. 1926: see Evraziiskaya khronika 4 (1926), 48-50.

16. University of Chicago, Weekly Calendar, 29 July-4 Aug. 1928. The university archivists at Cornell and Columbia have not been able to trace any information about the subjects of Mirsky's talk at their institutions.

17. For summary information on Karsavin's life and work, see Bibliographie des reuvres de Lev Karsavine. Etablie par Aleksandre Klementiev, Preface de Nikita Struve (Paris, 1994). On Karsavin's role in the Eurasian movement, see Claire Hauchard, 'L. P. Karsavin et le mouvement eurasien: de la critique a l'adhesion', Revue des Etudes Slaves 68 (3) (1996), 36o-5.

18. Cited in 'K istorii evraziistva. 1922-1924 gg.', in Rossiiskii arkhiv: Istoriya otechestva v svide-tel' stvakh i dokumentakh XVIII-XX vv.', v (Moscow, 1994), 494.

19. There is no evidence for the assertion (see Lev Karsavine: Bibliographie, 13) that in 1927 Karsavin turned down an offer made by Mirsky to take up a post at Oxford; this is one of many mysterious references to Mirsky's having some sort of Oxford association while he was in England. The offer may have had something to do with H. N. Spalding, who lived at Shotover Cleve near Oxford, rather than with the University of Oxford.20. See S. S. Khoruzhy, 'Karsavin, evraziistvo i VKP', Voprosy filosofii 2 {1992), 84-7. See also A. B. Sobolev, '"Svoya svoikh ne poznasha": Evraziistvo, L. P. Karsavin i drugie', Nachala 4 (1992), 49-58.

21. 'The Eurasian Movement', repr. in Uncollected Writings on Russian Literature, 245.

22. Trubetskoy was something of a whited sepulchre, though; the letters he wrote to his close friend Roman Jakobson during the early years of the Eurasian movement show that he slyly relished the potential political resonance of his publications. See especially the letters of 1922 in Trubetzkoy 's Letters and Notes. Prepared for publication by R. Jakobson with the assistance of H. Baran, O. Ronen and M. Taylor (The Hague, 1975).

23. The last interrogation took place on 5 July 1940, but Efron was pronounced guilty only on 6 July 1941, and then was not executed until 16 Oct. 1941.

24. The materials on this subject that beyond reasonable doubt once existed in Mirsky's GPU files, consisting of the transcripts of those interrogations at which certain aspects of Eurasianism were discussed, have been removed, probably to use against Efron and the others who came back at about the same time as Mirsky (who had been arrested more than two years before Efron was repatriated). Efron's depositions have not been published in full; for extracts and summary, see M. Feinberg and Yu. Klyukin, 'Po vnov' otkryvshimsya obstoyatel'stvam', in Bolshevo: Literaturnyi istoriko-kraevedcheskii al'manakh (Moscow, 1992), 145-66, and Irma Kudrova, Gibel' Mariny Tsvetaevoi (Moscow, 1992), 95-156.

25. Mirsky, 'The Eurasian Movement', 244.

26. Geoffrey Bailey, The Conspirators (London, 1971); Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky, KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev (London, etc., 1990), 43-114. See also A. V. Sobolev, 'Polyusa evraziistva', Novyi mir I (1991), 180-2.

27. S. L. Voitsekhovsky, Trest (London, Ont., 1974). Andrew and Gordievsky seem not to have known about this book. Voitsekhovsky apparently knew Bailey's book, but manifestly did not understand very much of what it has to say. There is also a fictionalized Soviet account of the Trust, based on conversations with Langovoy, the chief agent involved: Lev Nikulin, 'Mertvaya zyb'', Moskva 6 (1965), 5-90, and 7 (1965), 47-141. On Mirsky's acquaintanceship with Nikulin, see Chapter 7 below.

28. A. V. Sobolev, 'Knyaz' N. S. Trubetskoy i evraziistvo', Literaturnaya ucheba 6 (1991), 127.

29. See Suvchinsky's letter to Trubetskoy of 7 Oct. 1924: 'K istorii evraziistva', 487-8.

30. 'Col. Peter Malevsky Malevitch stayed with us often when my father was writing that book. I think he did something to inspire it' (Anne Spalding, unpublished letter to G. S. Smith, 5 Nov. 1974).

31. On the editorial disagreements before and during the establishment of the newspaper, see Irina Shevelenko, 'K istorii evraziiskogo raskola 1929 goda', Stanford Slavic Studies 8 (1994), 376-416.

32. Kingsley Martin (1897-1969) taught at the London School of Economics from 1923 to 1927, worked on the Manchester Guardian from 1927 to 1931, and then edited the New Statesman and Nation from 1932 to 1962.

33. Galsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1862-1932) was a Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and a part-time lecturer at the London School of Economics.

34. D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, 'Dve smerti: 1837-1930', repr. in Stikhotvoreniya: Stat'i o russkoi poezii (Berkeley, Calif., 1997), 135.

35. D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, 'O Tolstom', repr. in Mirsky, Uncollected Writings on Russian Literature, 293.

36. D. S. Mirsky, 'Yugo-zapad V. Bagritskogo', repr. in Stikhotvoreniya: Stat' i o russkoi poezii, compiled and ed. G. K. Perkins and G. S. Smith (Berkeley, Calif., 1997), 110.

37. D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, 'Khlebnikov', repr. in Uncollected Writings on Russian Literature, 294-7; 'Chekhov', repr. ibid. 298-302.

38. D. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, 'Literatura i kino', Evraziya 15 (2 Mar. 1929), 6; Mirsky also reviewed Pudovkin's film Potomok Chingiskhana, Evraziya, 20 Apr. 1929, 8 (this film is known in English as Storm over Asia).

39. Mirsky published two articles about these developments: 'Posle angliiskikh vyborov', Evraziya 29 (22 June 1929), 4, and 'Pervye shagi "rabochego" kabineta v Anglii', Evraziya 31 (13 July 1929), 5.

40. I. V. Stalin, 'God velikogo pereloma: K XII godovshchine Oktyabra', published in both Pravda and Izvestiya on 7 Nov. 1929; see I. V. Stalin, Sochineniya (13 vols., Moscow, 1946-51), xii (1949), 118-35.

41. For Berlin's account, see Smith, The Letters of D. S. Mirsky to P. P. Suvchinskii, 223-4.

42. Anne Spalding, unpublished letter to G. S. Smith, 29 Aug. 1974.

43. 'Why I Became a Marxist', Daily Worker 462 (30 June 1931), 2.

44. Grigory Vasilievich Aleksandrov (1903-84), Eisenstein's assistant on his first four films travelled abroad with him during 1929-31, and later became a very successful Soviet director.

45. Dorothy Galton, 'Sir Bernard Pares and Slavonic Studies in London University, 1919-39', Slavonic and East European Review 46 (107) (1968), 481-91.

46. Ibid.

47. Slavonic Review 7 (20) (1929), 512.

48. 'Introduction', in Dostoevsky's Letters to His Wife, trans. Elizabeth Hill and Doris Mudie (London, 1930), pp. ix-xiv.

49. Elizabeth Hill, unpublished letter to G. S. Smith, 31 Jan. 1974. Hill (1900--96) was born in St Petersburg, and taught at Cambridge from 1936 until her retirement in 1968 from the Chair of Slavonic Studies, to which she had been elected in 1948.

50. Unpublished diary entry, E. H. Carr archive, King's College, Cambridge; I am grateful to Jonathan Haslam for this reference.

51. 'Preface', in E. H. Carr, Dostoevsky (1821-1881): A New Biography (London, 1931), unpaginated.

52. E. H. Carr, unpublished letter to G. S. Smith, 1 Feb. 1974.

53. Guershoon's thesis was eventually published as Certain Aspects of Russian Proverbs (London, 1941). Bertha Malnick's first book offers a highly informative but now embarrassingly uncritical introduction to the Russia Mirsky went back to: Everyday Life in Soviet Russia, with drawings by Pearl Binder (London, 1938). On Helen Muchnic, see Chapter 4 above, n. 84.

54. For detailed information about Vera's life and the Russian texts of her letters to Mirsky, see Richard Davies and G. S. Smith, D. S. Mirsky: Twenty-Two Letters (1926-34) to Salomeya Halpern; Seven Letters (1930) to Vera Suvchinskaya (Traill)', Oxford Slavonic Papers n.s. 30 (1997), 91-122.

55. There is a vivid representation of Guchkov and his political activities particularly his plan for a coup d'etat in 1916, in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's Krasnoe koleso ('The Red Wheel).

56. See Irma Kudrova, 'Vera Treil, urozhdennaya Guchkova: Po materialam doprosov na Lubyanke', Russkaya mysl' 4068 (9-15 Mar. 1995), 11-12. It is clear from this article that Vera repeated to Kudrova many of the things she had said in her interviews with me.

57. Vera gave me this letter, one of the few personal documents that survived her mother's auto-da- fe after her daughter was arrested in 1940, in the course of our interviews in 1974. I duly gave it to Leeds Russian Archive, and it was first published without permission in Russia: see Zvezda 10 (1992), 34-6, and again in Marina Tsvetaeva, Sobranie sochinenii v semi tomakh (Moscow, 1995), vii: Pis'ma, 181.

58. D. S. Mirsky, Lenin (Boston and London, 1931), 190.

59. Vallee du Rhone: Cevennes (Paris, 1927), 10. Morateur, at 3 rue du President Carnot was the premier eating-place in the city.

6o. Helene Izvolsky worked for the Paris weekly Detective as an investigative journalist; among other cases, she was assigned the kidnapping of General Kutepov, but 'The police were as confounded as I was. I found the "case of the vanishing General" so scary that I turned it over to a reporter with stronger nerves than mine': No Time to Grieve (Philadelphia, 1985), 175. General A. P. Kutepov ( 1882-1930 ), on whose staff Mirsky had served when Kutepov's army captured Oryol at the height of the White success in the Civil War, in emigration became the president of the Russian General Military Union (ROVS), the principal ex-servicemen's organization and a prime target of GPU counter-intelligence. Kutepov was kidnapped on the street in Paris in broad daylight on 26 Jan. 1930, and never seen again.

61. This is chronologically the last reference in Mirsky's correspondence to Pyotr Arapov. Which other Arapov was present on this occasion I do not know; perhaps it was Pyotr Arapov's brother Kirill. It is possible that Pyotr was repatriated because he had something to do with the abduction of General Kutepov. There is also a private reason for Mirsky's mentioning Arapov to Vera. During our conversations in 1974, Vera told me that there had been two great loves in her life. One was Bruno von Salemann, a German Communist she met in France during the early part of the Second World War; the other was Pyotr Arapov. I never discovered when her affair with Arapov took place, and what relationship if any it had to her feelings for Mirsky in 1930. On Vera's affair with von Salemann, see her novel The Cup of Astonishment (London, 1944), published under the pseudonym 'Vera T. Mirsky'.

62. This village in Haute Savoie was the location of the Chateau d'Arcine, a boarding-house and sanatorium run by the Shtrange family, who were Russians and Communist sympathizers; they went back to Russia after the Second World War. Sergey. Efron went there on 23 Dec. 1929, after a recurrence of his tuberculosis. See Davies and Smith, D. S. Mirsky: Twenty-Two Letters', 118.

63. 'Dve smerti: 1837-1930', repr. in Mirsky, Stikhotovoreniya: Stat'i o russkoi poezii, 127.

64. Ibid. 134.

65. On 7 Sept. 1932 Gorky sent a copy of Mirsky's essay to Stalin, saying that his opinion of it would be important in connection with setting up the proposed Literary Institute. Stalin seems not to have replied. See '"Zhmu vashu ruku, dorogoi tovarishch" ', Novyi mir 9 (1998), 170.

66. For an expert examination of this question, see Karl Aimermakher [Eimermacher], 'Sovetskaya literaturnaya politika mezhdu 1917-m i 1932-m , m V tiskakh ideologii. Antologiya literaturno-politicheskikh dokumentov, 1917-1927 (Moscow, 1992), 3-61.

67. The most instructive treatment of the period leading up to the reform of 1932 is still Edward J. Brown, The Proletarian Episode in Russian Literature, 1928-1932 (New York, 1953); it has been supplemented by the previously secret documentation in D. L. Babichenko (ed.), 'Schast'e literatury': Gosudarstvo i pisateli (Moscow, 1997).

68. The name means 'Hillocks', and is unrelated etymologically to Gorky's pseudonymous surname, which means 'The Bitter One'.

69. See Kaznina and Smith, 'D. S. Mirsky to Maksim Gor'ky: Sixteen Letters (1928-1934)'.

70. D. S. Mirsky, Russia: A Social History (London, 1931), p. ix.

71. 'Letters of Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky to Sir B. Pares, 1922-1931', British Library, Add. MS 49,604.

72. Dorothy Galton said that this review was the real reason for the break between Mirsky and Pares: see 'Sir Bernard Pares and Slavonic Studies', 487.

73. In a letter to Sergey Efron of 19 May 1929 that has been preserved with the letters to Suvchinsky, Mirsky writes: 'I consider it a great honour to speak at M[arina] l[vanovna's] evening, but I'm afraid that 1) I'll speak badly; 2) my participation will keep many people away. No?'; see Smith, The Letters of D. S. Mirsky to P. P. Suvchinskii, 217.

74. Davies and Smith, 'D. S. Mirsky: Twenty-Two Letters', 176.

75. Raisa Nikolaevna Lomonosova (1888-1973) was the wife of the railway engineer Yury Vladimirovich Lomonosov (1876-1952), who decided to stay in the West rather than going back to the USSR in 1927; her primary residence was in England. Lomonosova furnished material assistance to both Pasternak and Tsvetaeva. She seems not to have been personally acquainted with Mirsky; even though he is mentioned in her correspondence with the two poets. On Lomonosova, see the annotation by Richard Davies to 'Pis' rna Mariny Tsvetaevoi k R, N .. Lomonosovoi (1928-1931 gg.). Publikatsiya Richarda Devisa, podgotovka teksta Lidii Shorroks', Minuvshee 8 (1989), 208-73. The texts of the letters and some annotations are repr. in Tsvetaeva, Sobranie sochinenii v semi tomakh, vii. 313-47.

76. 'Pis' rna Mariny Tsvetaevoi k R. A. Lomonosovoi', 244; see also Tsvetaeva, Sobranie sochinenii, vii. 328.

77. 'Pis'ma Mariny Tsvetaevoi k R. A. Lomonosovoi', 247; Tsvetaeva, Sobrame sochmenii, vii. 330.

78. Ibid. vi. 392.

79. G. Ya. Sokolnikov (1888-1939) was appointed Soviet ambassador to London in 1929 as a result of his opposition to Stalin. Mirsky was invited to a PEN monthly dinner at the Garden Club, Chesterfield Gardens, on 1 Mar. 1932, presided over by Louis Golding, with 'Mrs Sokolnikoff' as the guest of honour (unpublished letters to D. S. Mirsky from the Secretary of London PEN Club, Jan. 1932, Harry Ransome Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin). Sokolnikov's wife was the prominent historical novelist Galina Serebryakova (1905-80), who among other things worked on her life of Marx while she was in London. Serebryakova and Mirsky saw each other back in Russia; they were among the group of writers invited out to Gorky's country house to meet Romain Rolland on 9 June 1935; see Chapter 7 below. Serebryakova survived 17 years in the GULag, and achieved notoriety when she made a pro-Stalin speech at the XX Party Congress in 1956, when Stalinism was officially 'unmasked'.

80. 'Why I Became a Marxist', Daily Worker, 30 June 1931, 2.

81. See announcements in the Daily Worker, 17 June 1931, 2, and 20 June 1931, 2.

82. I. M. Gronsky, 'Beseda o Gor'kom: Publikatsiya M. Nike', Minuvshee 10 (1990), 71.

83. A fleeting reference in a letter of Oct. 1936 to Dorothy Galton suggests that Mirsky might have known Samuil Borisovich Kagan, the Soviet resident in Britain who controlled the 'climate of treason'; on Kagan, see Andrew Boyle, The Climate of Treason, rev. edn (London, 1980). In his autobiographical statement of 1936, as someone who could vouch for his activities before he returned to Russia Mirsky gave the name of one A. F. Neiman, who was attached to the Soviet Embassy; again, the nature of their contacts remains to be discovered (see V. V. Perkhin, 'Odinnadtsat' pisem (1922-1937) i avtobiografiya (1936) D. P. Svyatopolk-Mirskogo', Russkaya literatura I (1996), 259).

84. Galton, 'Sir Bernard Pares and Slavonic Studies', 485. Vera Traill told me the same thing.

85. Mirsky means the Union of Returnees (Soyuz vozvrashchentsev), set up in Paris by the Soviet authorities to stimulate and control pro-Soviet sentiment among the emigration; Sergey Efron later worked for this organization.

86. Cited in Losskaya, Marina Tsvetaeva v zhizni, 196.

87. Sir Bernard Pares, A Wandering Student (Syracuse, NY, 1948), 291.

88. Mirsky, Uncollected Writings on Russian Literature, 364-5.

89. Ibid. 366-7.

90. For the text of this letter, see O. A. Kaznina, 'N. S. Trubetskoy i krizis evraziistva', Slavyanovedenie 4 (1995), 89-95.

91. See John Callaghan, Rajani Palme Dutt: A Study in British Stalinism (London, 1993), 128-72.

92. Pares, A Wandering Student, 291.

93. Unpublished letter, Michael Florinsky Deposit, Bakhmeteff Archive, Columbia University; the reply from Florinsky is from the same source.

94. D. S. Mirsky, 'Bourgeois History and Bourgeois Materialism', Labour Monthly 13 (7) ( 1931), 453-9; 'The Philosophical Discussion in the C.P.S.U. in 1930-31', ibid. 13 (9) (1931), 649-56.

95. D. S. Mirsky, 'The Outlook of Bertrand Russell', Labour Monthly 14 (1932), 113-19 (a review of The Scientific Outlook); 'Mr Wells Shows His Class', Labour Monthly 14 (1932), 383-7 (a review of The Work, Wealth, and Happiness of Mankind).

96. Jonathan Ree, Proletarian Philosophers: Problems in Socialist Culture in Britain, 1900-1940 (Oxford, 1984), 71-2.

97. Gramsci (1891-1937) had been in prison since 1926; he was not in Stalin's GULag, though, but in a prison of Mussolini's, where conditions were not dissimilar from those the leading Russian revolutionaries had enjoyed before 1917. Gramsci wrote to Tatyana, the sister of his Russian wife, Yulka, from Turi prison on 3 Aug. 1931: '[It] is quite surprising how ably Mirsky has made himself master of the central nucleus of Historic Materialism, displaying in the process such a lot of intelligence and penetration. It seems to me that his scientific position is all the more worthy of note and of study, seeing that he shows himself free of certain cultural prejudices and incrustations which infiltrated the field of the theory of history in a parasitic fashion at the end of the last century and the beginning of this one, in consequence of the great popularity enjoyed by Positivism': Gramsci's Prison Letters, trans. and introduced by Hamish Hamilton (London, 1988), 153-4.

98. See Perkhin, 'Odinnadtsat' pisem (1922-1937) i avtobiografiya (1936)', 258.

99. See Nina Lavroukine and Leonid Tchertkov, D. S. Mirsky: profil critique et bibliographique (Paris, 1980), 41.

100. See Leopold Labedz, 'Isaac Deutscher's "Stalin": An Unpublished Critique', Encounter 52 (1) (1979), 68.

101. On Mirsky and MacDiarmid, see G. S. Smith, 'D. S. Mirsky and Hugh MacDiarmid: A Relationship and an Exchange of Letters (1934)', Slavonica 2/3 (1996-7), 49-60.

102. See Peter McCarey, Hugh MacDiarmid and the Russians (Edinburgh, 1987).

103. C. M. Grieve, 'Modern Russian Literature', New Age 37 (8) (25 June 1925), 92; the review is hostile, especially with reference to Mirsky's comments on Chekhov.

104. C. M. Grieve, 'Contemporary Russian Literature', New Age 40 (I) (4 Nov. 1926), 9. Here, MacDiarmid is almost entirely positive: 'a model book of its kind .... These 330 pages have a readability and, indeed, a raciness any literary historian might envy. I know no parallel to his feat.'

105. M. Gutner (ed.), Antologiya novoi angliiskoi poezii (Leningrad, 1937), 392.

106. Hugh MacDiarmid, In Memoriam James Joyce: From a Vision of a World Language (Glasgow, 1955); see The Collected Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid (2 vols., Manchester, 1993), ii. 736.

107. 'Two Aspects of Revolutionary Nationalism', Russian Life 5 (1922), 172-4; 'Russian Post-Revolutionary Nationalism', Contemporary Review 124 (1923), 191-8.

108. MacDiarmid was expelled from the Communist Party for nationalist deviation in 1938, and rejoined it -- as usual for him, against the grain -- in 1956. In between, he rejoined the Scottish National Party (as it had then become) in 1942, and left it in 1948.

109. In an article whose date of writing is unclear, Mirsky described MacDiarmid as 'A radical and Scottish nationalist in politics, a confused vitalist in philosophy': 'Angliiskaya literatura', in Entsiklopedicheskii slovar' russkogo bibliograficheskogo instituta Granat, 7th rev. edn, supplementary vol. i (Moscow, 1936), cols. 434-5.

110. The Collected Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid, i. 298.

111. Beatrice Webb's Diaries, 1924-1932, ed. Margaret Cole (London, 1956), 301. On 7 Jan. 1932 Mirsky informed Miss Galton that the Webbs had invited him for a weekend, and commented: 'This is rather amusing (the idea rather than the fact).'

112. Kingsley Martin, Father Figures: A First Volume of Autobiography, 1897-1931 (London, 1966), 201.

113. D. S. Mirsky, The Intelligentsia of Great Britain, trans. Alec Brown (London, 1935), 205,

114. This delegation to the International History of Science Congress, held in London in the summer of 1931, also visited Cambridge; among its members was Nikolay Bukharin. See Gary Werskey, The Visible College (London, 1978), and Science at the Crossroads: Essays by N I. Bukharin and Others, 2nd edn (London, 1971).

115. Mirsky, The Intelligentsia of Great Britain, 235-6.

116. See J. W. Boag, P. E. Rubinin, and D. Schoenberg (eds.), Kapitza in Cambridge and Moscow: Life and Letters of a Russian Physicist (Amsterdam, 1990).

117. Esther Salaman, 'Prince Mirsky', Encounter 54 (I) (1980), 93-4. True to his officer's code, Mirsky doubtless means that the appropriate response would be to call out the lady's husband for allowing her to speak in this way in public.

118. Understand the Weapon, Understand the Wound: Selected Writings of John Cornford, with some Letters of Frances Cornford, ed. Jonathan Galassi (Manchester, 1976), 143.

119. Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightly, 'The Cambridge Marxists', in Philby: The Spy who Betrayed a Generation, rev. edn (London, 1977), 64-70.

120. Cited in Lavroukine and Tchertkov, Mirsky, 41.

121. Mirsky reported to Dorothy Galton that he spoke in Amsterdam on 18 Apr., on what occasion he does not say.

122. On Munzenberg (1889-1940), see Stephen Koch, Double Lives: Stalin, Willi Munzenberg and the Seduction of the Intellectuals (London, 1996).

123. Mirsky and Dobb made some sort of proposal to the Comintern about setting up a special section for intellectuals: see Callaghan, Rajani Palme Dutt, 133.

124. The Sickle Side of the Moon: The Letters of Virginia Woolf, v: 1932-1936, ed. Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Banks (London, 1979), 71.

125. Virginia Woolf, A Writer's Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf, ed. Leonard Woolf (London, 1953), 181-2.

126. A persistent rumour insists that there was more to Mirsky's private life than the relationship with Vera Suvchinskaya: 'his unsuccessful marriage to Vera Nikolaevna, Countess Buxhoeveden, which is what drove him to take that desperate deranged step with regard to the "Soviet paradise". I knew Vera Nikolaevna personally, and I know from her personally about these circumstances. She blamed herself for his downfall; every time the conversation turned to "Dima" she would say that she alone was to blame for the fact that he totally gave himself over to those monsters': unpublished letter by Marina Ledkovsky to Olga Kaznina, 10 June 1994, quoted with permission.

127. Gleb Struve, Russian Literature under Lenin and Stalin, 1917-1953 (London, 1972), 270.

128. Hugh Dalton, The Fateful Years (London, 1957), cited in Kingsley Martin, Editor (London, 1968), 60. Dalton visited the USSR in 1932, and he was not alone; indeed, 'The entire British intelligentsia has been in Russia this summer', declared Kingsley Martin: Low's Russian Sketchbook. Drawings by Low, text by Kingsley Martin (London, 1932), 9. Dalton is mentioned among other leading left-wing politicians as a person to contact in Mirsky's letter to Suvchinsky of 18 Oct. 1928.

129. Letter to Suvchinsky, 8 Oct. 1924. The phrase in Russian is: Gadkaya prezritel' naya gumannost', zhalost', prezrenie i brezglivost' k chelovechestvu, ni odnoi umnoi mysli.