by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/3/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

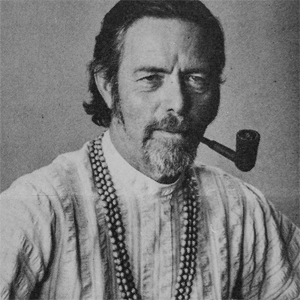

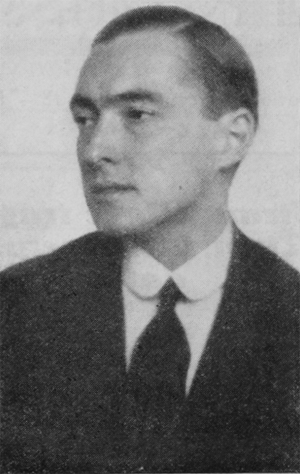

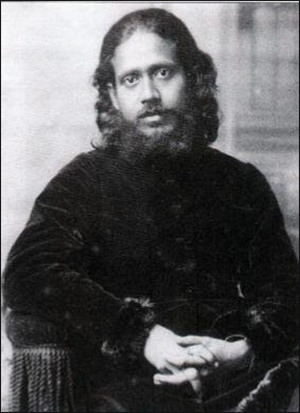

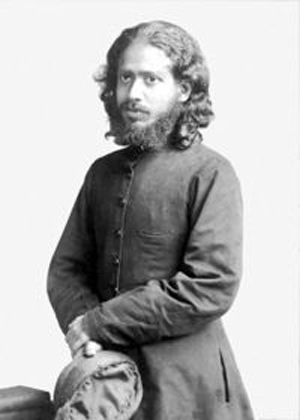

Mohini Chatterji, 1884

Mohini Mohun Chatterji (1858 - 1936) was a Bengali attorney and scholar who belonged to a prominent family that for several generations had mediated between Hindu religious traditions and Christianity.[1] He joined the Theosophical Society in 1882 and became Assistant Secretary of the Bengal branch. Later that year he became a chela in probation of the Mahātmā Koot Hoomi, and saw apparitions of Mahatmas on five or six occasions.[2] He eventually failed as a chela, and resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1887, after only five years of membership.

Early life and education

Mr. Chatterji, usually known as Mohini, was born in 1858 into a Brahmin family, descended from Hindu reformer Rammohan Roy.[3] He attended university in Calcutta, and was awarded Bachelor of Laws and Master of Arts degrees. His wife was the niece of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.[4]

Theosophical Society involvement

Mohini became a member of the Bengal Theosophical Society on April 16, 1882. According to Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett, "When HSO opened the first Theosophical Sunday School in Calcutta on March 10, 1883, with 17 boys, Mohini was appointed their teacher".[5]

Being a chela of Master K.H., he gave evidence to the Society for Psychical Research concerning the reality of psychic phenomena at Adyar,[6] in what came to be known as the Hodgson investigation.

Mohini worked as private secretary to H. S. Olcott and accompanied him and Mme. Blavatsky on their European tour in 1884:

The purpose of his trip to Europe was seemingly to give the members there some assistance in understanding the Eastern doctrines which had been brought into prominence by APS in his book Esoteric Buddhism."[7]

From a letter from Mme. Blavatsky to Mr. Sinnett, it would appear that he was going to be used in a similar manner as Babaji was:

On February 17th Olcott will probably sail for England on various business, and Mahatma K. H. sends his chela, under the guise of Mohini Mohun Chatterjee, to explain to the London Theosophists of the Secret Section — every or nearly every mooted point and to defend you and your assumptions. You better show Mohini all the Master's letters of a non-private character — saith the Lord, my Boss — so that by knowing all the subjects upon which he wrote to you he might defend your position the more effectually — which you yourself cannot do, not being a regular chela. Do not make the mistake, my dear boss, of taking the Mohini you knew for the Mohini who will come. There is more than one Maya in this world of which neither you nor your friends and critic Maitland is cognisant. The ambassador will be invested with an inner as well as with an outer clothing. Dixit.[8]

Mohini was present in London in 1884 when the young German artist Hermann Schmiechen painted the Portraits of the Masters. He was described by Laura C. Holloway as being “nearer the Master than all others in the room, not even excepting H.P.B.”[9]

Laura Carter Holloway-Langford was an American journalist and clairvoyant who became a chela of the Mahatmas...

She married Junius Brutus Holloway, Lieutenant in the Union Army, in 1862, and a friend of the Henry Clay family. They had one child, Charles, in 1864. However, the marriage quickly fell apart, and ended in divorce. Laura moved to New York and took up a career as an editor and writer.

In April, 1890, Mrs. Holloway married Colonel Edward L. Langford, secretary and treasurer of the Brooklyn and Brighton Beach Railway, and president of the Fulton Street elevated road. He had served with distinction in the Civil War.[2]Laura Carter Holloway, also known as Laura Holloway-Langford, was born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1843, one of the fourteen children of Samuel Carter, hotel keeper, and Ann Vaulx Carter. She was educated at the Nashville Female Academy, and married Lieutenant Junius Brutus Holloway of the Union Army in 1862. They had a son, George Holloway, that same year, but the marriage was not a happy one and the pair quickly separated.

At the end of the war Sam Carter moved his family to New York, where Laura began a career as an author and journalist. She published her first book, The Ladies of the White House, in 1870, and its sales made her independently wealthy. That year she also became the literary and women’s page editor at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper. Alongside her journalism, she continued to write books, among them The Hearthstone or Life at Home, a Household Manual (1883), The Mothers of Great Men and Women…(1883), Chinese Gordon, the Uncrowned King (1885), Five Years of Theosophy (1885), The Buddhist Diet-Book (1886), The Woman’s Story (1888), and Atma Fairy Stories (1903).

Holloway’s interests included theosophy, the Shakers, phrenology, the occult, vegetarianism and social reform. She is also considered an important force in the dissemination of ideas on Eastern religions. In 1884 she met Helena Blavatsky, leader of the theosophist movement, and worked with the theosophists for about six months. She was also a leader of Brooklyn’s Seidl Society, the aim of which was to sponsor concerts at Brighton Beach to be available at low cost to working class women. Through this activity she came into contact with Susan B. Anthony, as well as her future husband, Edward L. Langford, whom she married in 1890...

Colonel Edward Langford was deputy police commissioner of Brooklyn, and later an officer of the Brooklyn & Brighton Beach Railroad that ran from Prospect Park to the Brighton Beach Hotel. He was also active in the affairs of the Seidl Society. Colonel Langford died in 1902.

After his death, and through her friendship with Eldress Anna White, Holloway became more involved with the Shakers, and in 1906 she put down a deposit on a farm in New Lebanon, Columbia County, NY. Her son George retired from the army in 1911 and came to Upper Canaan to manage the farm, but on his sudden death from heart disease in 1914, Holloway entered a period of financial difficulties and depression. The last years of her life were marred by poverty and struggles over the manuscript of a book she had written about Madame Blavatsky. Laura C. Holloway died in 1930.

-- Laura C. Holloway Letters, by Brooklyn Public Library

Mrs. Holloway was also a social activist and lecturer:

She gave readings of literature and poetry and lectured on such topics as coeducation and women journalists. Her most famous lecture, “The Perils of the Hour” (1870), concerned “the obstacles that check the advancement of woman.” A suffragist who knew Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Anna Dickinson, Laura nonetheless criticized “strong-minded women” and their masculine habits. She supported temperance, urging the New York City Board of Education to adopt anti-alcohol textbooks...

She also edited Kuffereth's Parsifal, translated from the French; and The Bayreuth of Wagner. She made numerous contributions to magazines and newspapers. Her love of music, and especially that of Wagner, led to formation of the Seidl Society of Brooklyn, of which she was president from 1887-1898. She was co-editor with Anton Seidl in the musical materials of The Standard Dictionary.

In the 1870s, Mrs. Holloway became aware of Theosophy. She read A. P. Sinnett's books Esoteric Buddhism and The Occult World. In 1883 she was admitted as a member of the Theosophical Society in New York. William Quan Judge signed the certificate.

In 1884, she traveled to Europe to meet Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (in Paris), and other Theosophists, including Francesca Arundale, young George S. Arundale, Mohini Chatterji, A. P. Sinnett, and others. She stayed about six months with Society members. At first she was a guest of Miss Francesca Arundale, and in June went to stay with the Sinnetts.

In July 1884, probably while at the house of Francesca Arundale, she wrote Man: Fragments of a Forgotten History with Mohini Chatterji, using the pseudonym "Two Chelâs". The work is published in 1885 by Reeves and Turner.

-- Laura C. Holloway, by Theosophy Wiki

In 1885, he went to Ireland to lecture, and helped to establish the Dublin Lodge of the TS. There, he produced a deep impression on Irish poets George Russell (Æ) and William Butler Yeats and is said to have influenced the oriental turn of their writings. Yeats wrote a poem entitled 'Mohini Chatterjee'.[/size][/b]

Mohini Chatterjee

by William Butler Yeats

I ASKED if I should pray.

But the Brahmin said,

'pray for nothing, say

Every night in bed,

'I have been a king,

I have been a slave,

Nor is there anything.

Fool, rascal, knave,

That I have not been,

And yet upon my breast

A myriad heads have lain.'''

That he might Set at rest

A boy's turbulent days

Mohini Chatterjee

Spoke these, or words like these,

I add in commentary,

'Old lovers yet may have

All that time denied --

Grave is heaped on grave

That they be satisfied --

Over the blackened earth

The old troops parade,

Birth is heaped on Birth

That such cannonade

May thunder time away,

Birth-hour and death-hour meet,

Or, as great sages say,

Men dance on deathless feet.'

The adulation he received from some of the European members fueled his pride and he showed poor judgment on several matters. In late 1885, Mohini became involved in scandal with female Theosophists. The case came to public attention when one of the women, in response to Blavatsky's criticisms, intended to publicize letters written to her by Mohini Chatterjee.[10] Mme. Blavatsky wrote to Mr. Sinnett in March 1886:

Mohini was sent, and at first won the hearts and poured new life into the L.L. He was spoiled by male and female adulation, by incessant flattery and his own weakness.[11]

Mohini resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1887 and went back to his former home in Calcutta, where he resumed his practice of law.

Writings

Mohini wrote poetry and prose in both English and his native Bengali.

He and Mrs. Holloway wrote Man: Fragments of Forgotten History, published in 1887 under the pseudonym "Two Chelâs".[12]

He translated The Crest-Jewel of Wisdom (Viveka-Cūḍāmaṇi) of Sankaracharya. He worked with G. R. S. Mead in translating the Upanishads in 1896, using the pseudonym J. C. Chattopadhyaya.[13]

Later years

Yeats and George Russell (Æ) believed that at the turn of the century Mohini was working as a lawyer in Bombay. According to Harbans Rai Bachchan, the last heard of him was that he was a blind old man living in London with his daughter, in the early 1930s.[14] Mohini died in February, 1936.

Online resources

Articles

• Mohini Mohun Chatterji at Theosopedia.

• Morality and Pantheism by Mohini Chatterji

• A Few Words on The Theosophical Organization by Mohini Mohun Chatterji and Arthur Gebhard

• On the Higher Aspects of Theosophic Studies by Mohini M. Chatterji

• Qualifications for Chelaship by Mohini M. Chatterjee

• On the Existence of the Mahatmas by Mohini M. Chatterji

• The Crest Jewel of Wisdom translated by Mohini M Chatterji

• Atmanatma-Viveka: Discrimination of Spirit and Not-Spirit translated by Mohini M Chatterji

Additional resources

See also references in:

• The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett

• A Short History of the Theosophical Society

• The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett

Notes

1. Diane Sasson, Yearning for the New Age (Bloomington, IN:Indiana University Press, 2012), 78.

2. A Casebook of Encounters with the Theosophical Mahatmas Case 29, compiled and edited by Daniel H. Caldwell

3. George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

4. ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

5. George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

6. ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

7. George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

8. A. Trevor Barker, The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett Letter No. XXVIII, (Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1973), ??.

9. Laura C. Holloway, “The Mahatmas and Their Instruments Part II,” The Word(New York), July 1912, pp. 200-206, available at The Blavatsky Archives Portraits of the Mahatmas

10. See The Open University web site

11. Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 14o (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 459.

12. The complete text is available at [1]

13. ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

14. See The Open University web site

********************************

Mohini Mohun Chatterji

by Theosophy Wiki

Accessed: 8/19/20

M. M. Chatterji

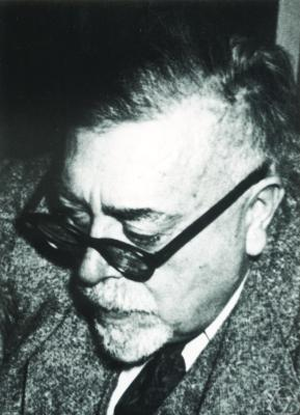

Mohini Mohun Chatterji (1858 - 1936) was a Bengali attorney and scholar who belonged to a prominent family that for several generations had mediated between Hindu religious traditions and Christianity.[1] He joined the Theosophical Society in 1882 and became Assistant Secretary of the Bengal branch. Later that year he became a chela in probation of the Mahâtma Koot Hoomi, and saw apparitions of Mahatmas on five or six occasions.[2] He eventually failed as a chela, and resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1887, after only five years of membership. Alternate spellings of his name are "Mohan" and "Chatterjee" (in Letter No. 57 in Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom, Second Series).

Early life and education

Mr. Chatterji, usually known as Mohini, was born in 1858 into a Brahmin family, descended from Hindu reformer Ram Roy.[3] He attended university in Calcutta, and was awarded Bachelor of Laws and Master of Arts degrees. His wife was the niece of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.[4]

Theosophical Society involvement

Joining the Society

Mohini became a member of the Bengal Theosophical Society on April 16, 1882, joining in Calcutta.[5] According to Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett, "When HSO opened the first Theosophical Sunday School in Calcutta on March 10, 1883, with 17 boys, Mohini was appointed their teacher".[6]

Receiving Mahatma Letters

Beginning in 1882, and continuing through at least 1884, Mohini received at least thirteen letters from Mahatma K. H. They were published in Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom, First Series and Second Series. These are links to the letters, in an approximation of chronological order:

Sept-Nov 1882

LMW 2 No. 58

LMW 1 No. 15

LMW 2 No. 57

LMW 2 No. 59

LMW 1 No. 14

1882-1884

LMW 2 No. 61

LMW 2 No. 62

LMW 1 No. 10

LMW 1 No. 11

LMW 1 No. 23

1884

LMW 2 No. 63

LMW 2 No. 62

LMW 1 No. 13

LMW 1 No. 52

European tour of 1884

Mohini worked as private secretary to H. S. Olcott and accompanied him and Mme. Blavatsky on their European tour in 1884:

The purpose of his trip to Europe was seemingly to give the members there some assistance in understanding the Eastern doctrines which had been brought into prominence by APS in his book Esoteric Buddhism."[7]

He rendered valuable aid with lectures and discourses both in Paris and London, and many European Theosophists still remember the brilliance of presentation of spiritual truths by the young Hindu.[8]

From a letter from Mme. Blavatsky to Mr. Sinnett, it would appear that he was going to be used in a similar manner as Babaji was:

On February 17th Olcott will probably sail for England on various business, and Mahatma K. H. sends his chela, under the guise of Mohini Mohun Chatterjee, to explain to the London Theosophists of the Secret Section — every or nearly every mooted point and to defend you and your assumptions. You better show Mohini all the Master's letters of a non-private character — saith the Lord, my Boss — so that by knowing all the subjects upon which he wrote to you he might defend your position the more effectually — which you yourself cannot do, not being a regular chela. Do not make the mistake, my dear boss, of taking the Mohini you knew for the Mohini who will come. There is more than one Maya in this world of which neither you nor your friends and critic Maitland is cognisant. The ambassador will be invested with an inner as well as with an outer clothing. Dixit.[9]

Collaboration with Laura C. Holloway

In July 1884, probably while at the house of Francesca Arundale, Mohini worked with Laura C. Holloway to write Man: Fragments of a Forgotten History. They used the pseudonym "Two Chelâs".[10] The work was published in 1885 by Reeves and Turner, but portions were incomplete due to the early departure of Mrs. Holloway before the final version could be completed.

Portraits of Masters

Mohini was present in London in 1884 when the young German artist Hermann Schmiechen painted the Portraits of the Masters. He was described by Laura C. Holloway as being “nearer the Master than all others in the room, not even excepting H.P.B.”[11]

Testifying for Hodgson Report

Being a chela of Master K.H., he gave evidence to the Society for Psychical Research concerning the reality of psychic phenomena at Adyar,[12] in what came to be known as the Hodgson investigation.

Lecture tour in Europe

In 1885, he went to Ireland to lecture, and helped to establish the Dublin Lodge of the TS. There, he produced a deep impression on Irish poets George Russell (Æ) and W. B. Yeats and is said to have influenced the oriental turn of their writings. Yeats wrote a poem entitled 'Mohini Chatterjee'.

The adulation he received from some of the European members fueled his pride and he showed poor judgment on several matters. In late 1885, Mohini became involved in scandal with female Theosophists. The case came to public attention when one of the women, in response to Blavatsky's criticisms, intended to publicize letters written to her by Mohini Chatterjee.[13] Mme. Blavatsky wrote to Mr. Sinnett in March 1886:

Mohini was sent, and at first won the hearts and poured new life into the L.L. He was spoiled by male and female adulation, by incessant flattery and his own weakness.[14]

Mohini resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1887 and went back to his former home in Calcutta, where he resumed his practice of law.

Writings

Mohini wrote poetry and prose in both English and his native Bengali.

He and Mrs. Holloway wrote Man: Fragments of Forgotten History, published in 1887 under the pseudonym "Two Chelâs".[15]

He translated the The Crest-Jewel of Wisdom (Viveka-Cūḍāmaṇi) of Sankaracharya. He worked with G. R. S. Mead in translating the Upanishads in 1896, using the pseudonym J. C. Chattopadhyaya.[16]

Later years

Yeats and George Russell (Æ) believed that at the turn of the century Mohini was working as a lawyer in Bombay. According to Harbans Rai Bachchan, the last heard of him was that he was a blind old man living in London with his daughter, in the early 1930s.[17] Mohini died in February, 1936.

Online resources

Articles

• Mohini Mohun Chatterji at Theosopedia.

• Morality and Pantheism by Mohini Chatterji

• A Few Words on The Theosophical Organization by Mohini Mohun Chatterji and Arthur Gebhard

• On the Higher Aspects of Theosophic Studies by Mohini M. Chatterji

• Qualifications for Chelaship by Mohini M. Chatterjee

• On the Existence of the Mahatmas by Mohini M. Chatterji

• The Crest Jewel of Wisdom translated by Mohini M Chatterji

• Atmanatma-Viveka: Discrimination of Spirit and Not-Spirit translated by Mohini M Chatterji

• Mohini Mohan Chatterji's Influence on W.B. Yeats by Dr. Suman Singh

Additional resources

See also references in:

• The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett

• A Short History of the Theosophical Society

• The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett

Notes

1. Diane Sasson, Yearning for the New Age (Bloomington, IN:Indiana University Press, 2012), 78.

2. A Casebook of Encounters with the Theosophical Mahatmas Case 29, compiled and edited by Daniel H. Caldwell

3. George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

4. ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

5. April 6, per Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1066 (website file: 1A/36).

6. George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

7. George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 223.

8. [Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom (book)|Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom, Second Series (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1925), 103.

9. A. Trevor Barker, The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett Letter No. XXVIII, (Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1973), ??.

10. Two Chelas, Man: Fragments of a Forgotten History, 1887. The complete text is available at the Canadian Theosophical Association

11. Laura C. Holloway, “The Mahatmas and Their Instruments Part II,” The Word (New York), July 1912, pp. 200-206, available at The Blavatsky Archives Portraits of the Mahatmas

12. ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

13. See The Open University web site

14. Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 140 (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 459.

15. The complete text is available at [1]

16. ”Chatterji, Mohini Mohun,” The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 172.

17. See The Open University web site