by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/18/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

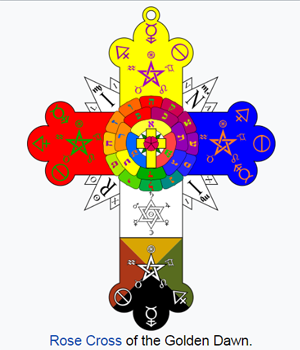

Rose Cross of the Golden Dawn.

Successor: Alpha et Omega; Stella Matutina; Isis-Urania Temple; A∴A∴

Formation: 1887

Extinction: 1903

Type: Magical organization

Headquarters: London

Location: United Kingdom

Chiefs of the Second Order: William Wynn Westcott (1888-1897); Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers(1897-1903)

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (Latin: Ordo Hermeticus Aurorae Aureae; or, more commonly, the Golden Dawn (Aurora Aurea)) was a secret society devoted to the study and practice of the occult, metaphysics, and paranormal activities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Known as a magical order, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was active in Great Britain and focused its practices on theurgy and spiritual development. Many present-day concepts of ritual and magic that are at the centre of contemporary traditions, such as Wicca[1][2] and Thelema, were inspired by the Golden Dawn, which became one of the largest single influences on 20th-century Western occultism.[3][4]

The three founders, William Robert Woodman, William Wynn Westcott and Samuel Liddell Mathers, were Freemasons. Westcott appears to have been the initial driving force behind the establishment of the Golden Dawn.

The Golden Dawn system was based on hierarchy and initiation like the Masonic lodges; however women were admitted on an equal basis with men. The "Golden Dawn" was the first of three Orders, although all three are often collectively referred to as the "Golden Dawn". The First Order taught esoteric philosophy based on the Hermetic Qabalah and personal development through study and awareness of the four Classical Elements as well as the basics of astrology, tarot divination, and geomancy. The Second or "Inner" Order, the Rosae Rubeae et Aureae Crucis (the Ruby Rose and Cross of Gold), taught magic, including scrying, astral travel, and alchemy. The Third Order was that of the "Secret Chiefs", who were said to be highly skilled; they supposedly directed the activities of the lower two orders by spirit communication with the Chiefs of the Second Order.

History

Cipher Manuscripts

Main article: Cipher Manuscripts

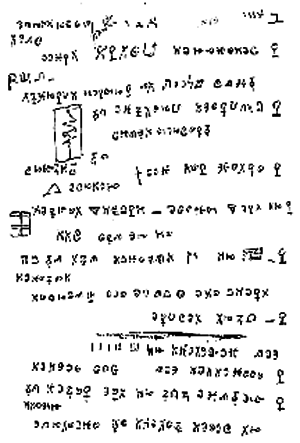

Folio 13 of the Cipher Manuscripts

The foundational documents of the original Order of the Golden Dawn, known as the Cipher Manuscripts, are written in English using the Trithemius cipher. The manuscripts give the specific outlines of the Grade Rituals of the Order and prescribe a curriculum of graduated teachings that encompass the Hermetic Qabalah, astrology, occult tarot, geomancy, and alchemy.

According to the records of the Order, the manuscripts passed from Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie, a Masonic scholar, to the Rev. A. F. A. Woodford, whom British occult writer Francis King describes as the fourth founder[5] (although Woodford died shortly after the Order was founded).[6] The documents did not excite Woodford, and in February 1886 he passed them on to Freemason William Wynn Westcott, who managed to decode them in 1887.[5] Westcott, pleased with his discovery, called on fellow Freemason Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers for a second opinion. Westcott asked for Mathers' help to turn the manuscripts into a coherent system for lodge work. Mathers in turn asked fellow Freemason William Robert Woodman to assist the two, and he accepted.[5] Mathers and Westcott have been credited with developing the ritual outlines in the Cipher Manuscripts into a workable format.[7] Mathers, however, is generally credited with the design of the curriculum and rituals of the Second Order, which he called the Rosae Rubae et Aureae Crucis ("Ruby Rose and Golden Cross" or the RR et AC).[8]

Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers in Egyptian setup performing a ritual in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

Founding of first temple

In October 1887, Westcott claimed to have written to a German countess and prominent Rosicrucian named Anna Sprengel, whose address was said to have been found in the decoded Cipher Manuscripts. According to Westcott, Sprengel claimed the ability to contact certain supernatural entities, known as the Secret Chiefs, that were considered the authorities over any magical order or esoteric organization. Westcott purportedly received a reply from Sprengel granting permission to establish a Golden Dawn temple and conferring honorary grades of Adeptus Exemptus on Westcott, Mathers, and Woodman. The temple was to consist of the five grades outlined in the manuscripts.[9][10]

In 1888, the Isis-Urania Temple was founded in London.[9] In contrast to the S.R.I.A. and Masonry,[10] women were allowed and welcome to participate in the Order in "perfect equality" with men. The Order was more of a philosophical and metaphysical teaching order in its early years. Other than certain rituals and meditations found in the Cipher manuscripts and developed further,[11] "magical practices" were generally not taught at the first temple.

For the first four years, the Golden Dawn was one cohesive group later known as "the Outer Order" or "First Order." An "Inner Order" was established and became active in 1892. The Inner Order consisted of members known as "adepts," who had completed the entire course of study for the Outer Order. This group of adepts eventually became known as the Second Order.[citation needed]

Eventually, the Osiris temple in Weston-super-Mare, the Horus temple in Bradford (both in 1888), and the Amen-Ra temple in Edinburgh (1893) were founded. In 1893 Mathers founded the Ahathoor temple in Paris.[9]

Secret Chiefs

Main article: Secret Chiefs

In 1891, Westcott's alleged correspondence with Anna Sprengel suddenly ceased. He claimed to have received word from Germany that she was either dead or that her companions did not approve of the founding of the Order and no further contact was to be made. If the founders were to contact the Secret Chiefs, apparently, it had to be done on their own.[9] In 1892, Mathers professed that a link to the Secret Chiefs had been established. Subsequently, he supplied rituals for the Second Order, calling them the Red Rose and Cross of Gold.[9] The rituals were based on the tradition of the tomb of Christian Rosenkreuz, and a Vault of Adepts became the controlling force behind the Outer Order.[12] Later in 1916, Westcott claimed that Mathers also constructed these rituals from materials he received from Frater Lux ex Tenebris, a purported Continental Adept.[13]

Some followers of the Golden Dawn tradition believe that the Secret Chiefs were not human or supernatural beings but, rather, symbolic representations of actual or legendary sources of spiritual esotericism. The term came to stand for a great leader or teacher of a spiritual path or practice that found its way into the teachings of the Order.[14]

Golden Age

By the mid-1890s, the Golden Dawn was well established in Great Britain, with over one hundred members from every class of Victorian society.[6] Many celebrities belonged to the Golden Dawn, such as the actress Florence Farr, the Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne, the Irish poet William Butler Yeats, the Welsh author Arthur Machen, and the English authors Evelyn Underhill and Aleister Crowley.

In 1896 or 1897, Westcott broke all ties to the Golden Dawn, leaving Mathers in control. It has been speculated that his departure was due to his having lost a number of occult-related papers in a hansom cab. Apparently, when the papers were found, Westcott's connection to the Golden Dawn was discovered and brought to the attention of his employers. He may have been told to either resign from the Order or to give up his occupation as coroner.[15] After Westcott's departure, Mathers appointed Florence Farr to be Chief Adept in Anglia. Dr. Henry B. Pullen Burry succeeded Westcott as Cancellarius—one of the three Chiefs of the Order.

Mathers was the only active founding member after Westcott's departure. Due to personality clashes with other members and frequent absences from the center of Lodge activity in Great Britain, however, challenges to Mathers's authority as leader developed among the members of the Second Order.[16]

Revolt

Toward the end of 1899, the Adepts of the Isis-Urania and Amen-Ra temples had become dissatisfied with Mathers' leadership, as well as his growing friendship with Aleister Crowley. They had also become anxious to make contact with the Secret Chiefs themselves, instead of relying on Mathers as an intermediary.[17] Within the Isis-Urania temple, disputes were arising between Farr's The Sphere, a secret society within the Isis-Urania, and the rest of the Adepti Minores.[17]

Crowley was refused initiation into the Adeptus Minor grade by the London officials. Mathers overrode their decision and quickly initiated him at the Ahathoor temple in Paris on January 16, 1900.[18] Upon his return to the London temple, Crowley requested from Miss Cracknell, the acting secretary, the papers acknowledging his grade, to which he was now entitled. To the London Adepts, this was the final straw. Farr, already of the opinion that the London temple should be closed, wrote to Mathers expressing her wish to resign as his representative, although she was willing to carry on until a successor was found.[18] Mathers believed Westcott was behind this turn of events and replied on February 16. On March 3, a committee of seven Adepts was elected in London, and requested a full investigation of the matter. Mathers sent an immediate reply, declining to provide proof, refusing to acknowledge the London temple, and dismissing Farr as his representative on March 23.[19] In response, a general meeting was called on March 29 in London to remove Mathers as chief and expel him from the Order.[20]

Splinters

In 1901, W. B. Yeats privately published a pamphlet titled Is the Order of R. R. & A. C. to Remain a Magical Order?[21] After the Isis-Urania temple claimed its independence, there were even more disputes, leading to Yeats resigning.[22] A committee of three was to temporarily govern, which included P.W. Bullock, M.W. Blackden and J. W. Brodie-Innes. After a short time, Bullock resigned, and Dr. Robert Felkin took his place.[23]

In 1903, A. E. Waite and Blackden joined forces to retain the name Isis-Urania, while Felkin and other London members formed the Stella Matutina. Yeats remained in the Stella Matutina until 1921, while Brodie-Innes continued his Amen-Ra membership in Edinburgh.[24]

Reconstruction

Once Mathers realised that reconciliation was impossible, he made efforts to reestablish himself in London. The Bradford and Weston-super-Mare temples remained loyal to him, but their numbers were few.[25] He then appointed Edward Berridge as his representative.[26] According to Francis King, historical evidence shows that there were "twenty three members of a flourishing Second Order under Berridge-Mathers in 1913."[26]

J.W. Brodie-Innes continued leading the Amen-Ra temple, deciding that the revolt was unjustified. By 1908, Mathers and Brodie-Innes were in complete accord.[27] According to sources that differ regarding the actual date, sometime between 1901 and 1913 Mathers renamed the branch of the Golden Dawn remaining loyal to his leadership to Alpha et Omega.[28][29][30][31] Brodie-Innes assumed command of the English and Scottish temples, while Mathers concentrated on building up his Ahathoor temple and extending his American connections.[29] According to occultist Israel Regardie, the Golden Dawn had spread to the United States of America before 1900 and a Thoth-Hermes temple had been founded in Chicago.[27][29] By the beginning of the First World War in 1914, Mathers had established two to three American temples.

Most temples of the Alpha et Omega and Stella Matutina closed or went into abeyance by the end of the 1930s, with the exceptions of two Stella Matutina temples: Hermes Temple in Bristol, which operated sporadically until 1970, and the Smaragdum Thallasses Temple (commonly referred to as Whare Ra) in Havelock North, New Zealand, which operated regularly until its closure in 1978.[32][33]

Structure and grades

Much of the hierarchical structure for the Golden Dawn came from the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia, which was itself derived from the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross.[34]

First Order

• Introduction—Neophyte 0=0

• Zelator 1=10

• Theoricus 2=9

• Practicus 3=8

• Philosophus 4=7

• Intermediate—Portal Grade

Second Order

• Adeptus Minor 5=6

• Adeptus Major 6=5

• Adeptus Exemptus 7=4

Third Order

• Magister Templi 8=3

• Magus 9=2

• Ipsissimus 10=1

The paired numbers attached to the Grades relate to positions on the Tree of Life. The Neophyte Grade of "0=0" indicates no position on the Tree. In the other pairs, the first numeral is the number of steps up from the bottom (Malkuth), and the second numeral is the number of steps down from the top (Kether).

The First Order Grades were related to the four elements of Earth, Air, Water, and Fire, respectively. The Aspirant to a Grade received instruction on the metaphysical meaning of each of these Elements and had to pass a written examination and demonstrate certain skills to receive admission to that Grade.

The Portal Grade was an "Invisible" or in-between grade separating the First Order from the Second Order.[35]

Known or alleged members

• Sara Allgood (1879–1950), Irish stage actress and later film actress in America

• Charles Henry Allan Bennett (1872–1923), best known for introducing Buddhism to the West

• Arnold Bennett (1867–1931), British novelist[36]

• Arthur Edward Waite (2 October 1857 – 19 May 1942) Mystic

• Edward W. Berridge (ca. 1843–1923), British homeopathic physician[1]:148–149

• Algernon Blackwood (1869–1951), English writer and radio broadcaster of supernatural stories[37]

• Anna de Brémont, American-born singer and writer.[38]

• Dario Carpaneda (1856 - 1916) Italian occultist and esotericism professor at the University of Lausanne.

• Paul Foster Case was not an original member of the Golden Dawn, but was a member of the successor organization, Alpha et Omega. He was an American occultist

• Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), author of Sherlock Holmes, doctor, scientist, and spiritualist.[39]

• Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), occultist, writer and mountaineer, founder of his own magical society.

• Florence Farr (1860–1917), London stage actress and musician[37]

• Robert Felkin (1853–1925), medical missionary, explorer and anthropologist in Central Africa, author

• Dion Fortune was not an original member of the Golden Dawn, rather a member of the offshoot Golden Dawn order the Stella Matutina. Dion Fortune Founded the Society of Inner Light.

• Frederick Leigh Gardner (1857–1930), British stock broker and occultist; published three-volume bibliography Catalogue Raisonné of Works on the Occult Sciences (1912)[40]

• Maud Gonne (1866–1953), Irish revolutionary, actress.

• Annie Horniman (1860–1937), British repertory theatre producer and pioneer; member of the wealthy Horniman family of tea-traders[37]

• Arthur Machen (1863–1947), leading London writer of the 1890s, author of acclaimed works of imaginative and occult fiction, such as "The Great God Pan", "The White People" and "The Hill of Dreams". Welsh by birth and upbringing.

• Gustav Meyrink (1868–1932), Austrian author, storyteller, dramatist, translator, banker, and Buddhist

• E. Nesbit (1858–1924), real name Edith Bland; English author and political activist

• Israel Regardie was not a member of the original Golden Dawn, but rather of the Stella Matutina, which he claimed was as close to the original order as could be found in the early 1930s (when he was initiated). Regardie wrote many respected and acclaimed books about magic and the Golden Dawn Order, including The Golden Dawn, The Tree Of Life, Middle Pillar, and A Garden of Pomegranates.

• Sax Rohmer, novelist, creator of the Fu Manchu character

• Charles Rosher (1885–1974), British cinematographer

• William Sharp (1855–1905), poet and author; alias Fiona MacLeod

• Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951), British-American artist and co-creator of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck

• Bram Stoker[41][42] (1847–1912), Irish writer best-known today for his 1897 horror novel Dracula

• John Todhunter (1839–1916), Aktis Heliou Irish poet and playwright who wrote seven volumes of poetry, and several plays

• Violet Tweedale (1862–1936), author.

• Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941), British Christian mystic, author of Mysticism: A Study in Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness

• Charles Williams (1886–1945), British poet, novelist, theologian, and literary critic

• W. B. Yeats (1865–1939), Irish poet, dramatist and writer.

Contemporary Golden Dawn orders

While no temples in the original chartered lineage of the Golden Dawn survived past the 1970s,[32][33] several organizations have since revived its teachings and rituals. Among these, the following are notable:

• The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Inc.

• The Open Source Order of the Golden Dawn

• The Fellowship of the Golden Dawn

• Golden Dawn Collegium Spiritu Sancti

• Golden Dawn Universum

• Golden Dawn Ancient Mystery School

• The Ordo Stella Matutina

• Sodalitas Rosae+Crucis et Solis Alati

• Orden Hermética de la Aurora Dorada

• Ordem Esotérica da Aurora Dourada no Brasil

• Hermetic Society of the Golden Dawn

• August Order of the Mystic Rose

• Order of the Golden Dawn in the Outer

See also

• A∴A∴

• Hermeticism

• Tattva

• Tattva vision

References

1. Colquhoun, Ithell (1975) The Sword of Wisdom: MacGregor Mathers & the Golden Dawn. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

2. Phillips, Julia (1991) History of Wicca in England: 1939 - present day. Lecture at the Wiccan Conference in Canberra, 1991.

3. Jenkins, Phillip (2000) Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History, pg. 74. "Also in the 1880s, the tradition of ritual magic was revived in London by a group of Masonic adepts, who formed the Order of the Golden Dawn, which would prove an incalculable influence on the whole subsequent history of occultism." USA: Oxford University Press.

4. Smoley, Richard (1999) Hidden Wisdom: A Guide to the Western Inner Traditions, ppg 102-103. "Founded in 1888, the Golden Dawn lasted a mere twelve years before it was shattered by personal conflicts. At its height it probably had no more than a hundred members. Yet its influence on magic and esoteric thought in the English-speaking world would be hard to overestimate." USA: Quest Books.

5. King, 1989, page 42-43

6. King, 1989, page 47

7. Golden Dawn researcher R. A. Gilbert has found evidence which suggests that Westcott was instrumental in developing the Order's rituals from the Cipher Manuscripts. See Gilbert's article, From Cipher to Enigma: The Role of William Wynn Westcott in the Creation of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, from Carroll Runyon's book Secrets of the Golden Dawn Cypher Manuscripts.

8. Regardie, 1993, page 92

9. King, 1989, page 43

10. Regardie, 1993, page 11.

11. King, 1997, page 35

12. King, 1989, page 44

13. King, 1989, page 46

14. Penczak, Christopher. Spirit Allies, p. 27. Red Wheel/Weiser Books. ISBN 1-57863-214-5

15. King, 1989, page 48

16. Raine, Kathleen (1976) [1972]. Liam Miller (ed.). Yeats, the Tarot and the Golden Dawn. New Yeats Papers. II (second ed.). Dublin: Dolmen Press. p. 6.

17. King, 1989, page 66

18. King, 1989, page 67

19. King, 1989, page 68-69

20. King, 1989, page 69

21. Melton, J. Gordon, editor, Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, v. 2 p. 1327, Gale Group, 2001 ISBN 0-8103-9489-8

22. King, 1989, page 78

23. King, 1989, page 94

24. King, 1989, pages 95-96

25. King, 1989, page 109

26. King, 1989, page 110

27. Regardie, 1993, page 33

28. King, 1971, p. 110-111

29. King, 1989, page 111

30. "The Golden Dawn ceased to exist by that name after October, 1901, replaced by Mathers' Alpha et Omega and the London group’s Order of the Morgan Rothe. No longer associated with the SRIA after 1902, Mathers continued to oversee a few temples until his death, when his wife, Moina, assumed supervision." Samuel Liddel MacGregor Mathers biography, Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, February 26, 2001

31. Golden Dawn Time Line, Chic Cicero and Sandra Tabatha Cicero, Llewellyn Encyclopedia

32. Gilbert, R. A. Golden Dawn Companion. Aquarian Press, 1986. ISBN 0-85030-436-9

33. Llewellyn Encyclopedia: "Golden Dawn Time Line"

34. The masonic career of A.E. Waite by Bro. R. A. Gilbert

35. Golden Dawn Research Center - What is the Golden Dawn?

36. Regardie, 1982, page 16

37. Regardie, 1982, foreword - page ix

38. Moyle, Franny (2011). Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs Oscar Wilde. Hachette UK. p. 118. ISBN 9781848544611.

39. http://moreintelligentlife.com/story/co ... iritualism

40. "Frederick Leigh Gardner", Biographies: Fringe freemasons, Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon (Freemasons) web site. Retrieved November 2008.

41. Ravenscroft, Trevor (1982). The occult power behind the spear which pierced the side of Christ. Red Wheel. p. 165. ISBN 0-87728-547-0.

42. Picknett, Lynn (2004). The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ. Simon and Schuster. p. 201. ISBN 0-7432-7325-7.

Bibliography

• Fra. A.o.C. (2002). A Short Treatise on the History, Culture and Practices of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

• Armstrong, Allan & R. A. Gilbert, eds. (1997). Golden Dawn: The Proceedings of the Golden Dawn Conference, London - 1997. Hermetic Research Trust.

• Cicero, Chic and Tabatha Cicero (1991). The New Golden Dawn Ritual Tarot. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0-87542-139-3

• Colquhoun, Ithell (1975). Sword of Wisdom: Macgregor Mathers and the Golden Dawn. Neville Spearman. ISBN 0-85435-092-6.

• Denisof, Dennis. "The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn." BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. 2013. http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_art ... -1888-1901.

• Greer, Mary K. (1994). Women of the Golden Dawn. Park Street. ISBN 0-89281-516-7.

• Greer, Mary K. & Darcy Kuntz (1999) The Chronology of the Golden Dawn. Holmes Publishing Group. ISBN 1-55818-354-X

• Gilbert, Robert A. (1983). The Golden Dawn: Twilight of the Magicians. The Aquarian Press. ISBN 0-85030-278-1

• Gilbert, Robert A. (1986). The Golden Dawn Companion. Weiser Books. ISBN 0-85030-436-9

• Gilbert, Robert A. Golden Dawn Scrapbook - The Rise and Fall of a Magical Order. Weiser Books (1998) ISBN 1-57863-037-1

• Howe, Ellic (1978). The Magicians of the Golden Dawn: A Documentary History of a Magical Order 1887-1923. Samuel Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-369-9.

• Jenkins, Phillip (2000) Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512744-7

• King, Francis (1971). The Rites of Modern Occult Magic. New York: Macmillan Company. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-158-933

• King, Francis (1989). Modern Ritual Magic: The Rise of Western Occultism. ISBN 1-85327-032-6

• King, Francis, ed. (1997). Ritual Magic of the Golden Dawn: Works by S. L. MacGregor Mathers and Others. Destiny Books. ISBN 0-89281-617-1

• Kuntz, Darcy, ed. (1996). The Complete Golden Dawn Manuscript. Introduction by R.A. Gilbert. Deciphered, Translated and Preface by Darcy Kuntz. (Golden Dawn Studies No 1.) Holmes Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1558183254

• Regardie, Israel, et al., eds. (1982). The Golden Dawn. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0-87542-664-6

• Israel Regardie|Regardie, Israel, et al., eds. (1989). The Golden Dawn: A Complete Course in Practical Ceremonial Magic. Llewellyn. ISBN 0-87542-663-8

• Regardie, Israel (1993). What You Should Know About the Golden Dawn (6th ed.). ISBN 1-56184-064-5

• Runyon, Carroll (1997). Secrets of the Golden Dawn Cipher Manuscripts. C.H.S. ISBN 0-9654881-2-8

• Smoley, Richard (1999). Hidden Wisdom: A Guide to the Western Inner Traditions. Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0844-2

• Suster, Gerald (1990). Crowley's Apprentice: The Life and Ideas of Israel Regardie. Weiser Books. ISBN 0-87728-700-7

• Wasserman, James (2005). The Mystery Traditions: Secret Symbols and Sacred Art. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books. ISBN 1-59477-088-3

External links

• The Golden Dawn FAQ (original from 1990s Usenet groups)

• The Golden Dawn Library Project

• Golden Dawn entries in Llewellyn Encyclopedia

• Golden Dawn Tradition, by co-founder Dr. W. Wynn Westcott

• Photocopies and the translation of the original Cipher Manuscripts

• Lots of GD material on display in Yeats exhibition including Ritual Notebooks.

• The Golden Dawn Roll Call

• Golden Dawn at Curlie

• Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn: Biographies of Members