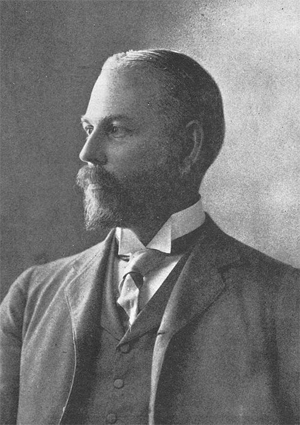

Part 2 of 2

Hedin and Nazi GermanyHedin's conservative and pro-German views eventually translated into sympathy for the Third Reich, and this would draw him into increasing controversy towards the end of his life. Adolf Hitler had been an early admirer of Hedin, who was in turn impressed with Hitler's nationalism. He saw the German leader's rise to power as a revival of German fortunes, and welcomed its challenge against Soviet Communism. He was not an entirely uncritical supporter of the Nazis, however. His own views were shaped by traditionalist, Christian and conservative values, while National Socialism was in part a modern revolutionary-populist movement. Hedin objected to some aspects of National Socialist rule, and occasionally attempted to convince the German government to relent in its anti-religious and anti-Semitic campaigns.

Hedin met Adolf Hitler and other leading National Socialists repeatedly and was in regular correspondence with them. The politely-worded correspondence usually concerned scheduling matters, birthday congratulations, Hedin's planned or completed publications, and requests by Hedin for pardons for people condemned to death, and for mercy, release and permission to leave the country for people interned in prisons or concentration camps. In correspondence with Joseph Goebbels and Hans Dräger, Hedin was able to achieve the printing of the Daily Watchwords year after year.[13]

The Nazis attempted to achieve a close connection to Hedin by bestowing awards upon him—later scholars have noted that "honors were heaped upon this prominent sympathizer."[14] They asked him to present an address on Sport as a Teacher at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin's Olympic stadium. They made him an honorary member of the German-Swedish Union Berlin (German: Deutsch-Schwedischen Vereinigung Berlin e.V.) In 1938, they presented him with the City of Berlin's Badge of Honor (German: Ehrenplakette der Stadt Berlin). For his 75th birthday on 19 February 1940 they awarded him the Order of the German Eagle; shortly before that date it had been presented to Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh. On New Year's Day 1943 they released the Oslo professor of philology and university rector Didrik Arup Seip from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp at Hedin's request[15] in order to obtain Hedin's agreement to accept additional honors during the 470th anniversary of Munich University. On 15 January 1943, he received the Gold Medal of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences (Goldmedaille der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften). On 16 January 1943 he received an honorary doctorate from the faculty of natural sciences of Munich University.[16] On the same day, the Nazis founded in his absence the Sven Hedin Institute for Inner Asian Research located at Mittersill Castle, which was supposed to serve the long-term advancement of the scientific legacy of Hedin and Wilhelm Filchner as Asian experts. However, it was instead misused by Heinrich Himmler as an institute of the Research Association for German Genealogical Inheritance (Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe e.V.).[17] On 21 January 1943, he was requested to sign the Golden Book of the city of Munich.

Hedin supported the Nazis in his journalistic activities. After the collapse of Nazi Germany, he did not regret his collaboration with the Nazis because this cooperation had made it possible to rescue numerous Nazi victims from execution, or death in extermination camps.

Senior Jewish German archeologist Werner Scheimberg, sent in the expedition by the Thule Society,[18] "had been one of the companions of the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin on his excursions in the East, with archaeological and to some extent esoteric purposes".[19]

Hedin was trying to discover the mythological place of Agartha and reproached the Jewish Polish explorer and visiting professor Antoni Ossendowski for having been gone where the Swedish explorer wasn't able to come, and thus was personally invited by Adolf Hitler in Berlin and honoured by the Führer during his 75th birthday feast.[20]Criticism of National SocialismJohannes Paul wrote in 1954 about Hedin:

Much of what happened in the early days of Nazi rule had his approval. However, he did not hesitate to criticize whenever he considered this to be necessary, particularly in cases of Jewish persecution, conflict with the churches and bars to freedom of science.[21]

In 1937 Hedin refused to publish his book Deutschland und der Weltfrieden (Germany and World Peace) in Germany because the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda insisted on the deletion of Nazi-critical passages. In a letter Hedin wrote to State Secretary Walther Funk dated 16 April 1937, it becomes clear what his criticism of National Socialism was in this time before the establishment of extermination camps:

When we first discussed my plan to write a book, I stated that I only wanted to write objectively, scientifically, possibly critically, according to my conscience, and you considered that to be completely acceptable and natural. Now I emphasized in a very friendly and mild form that the removal of distinguished Jewish professors who have performed great services for mankind is detrimental to Germany and that this has given rise to many agitators against Germany abroad. So I took this position only in the interest of Germany.

My worry that the education of German youth, which I otherwise praise and admire everywhere, is deficient in questions of religion and the hereafter comes from my love and sympathy for the German nation, and as a Christian I consider it my duty to state this openly, and, to be sure, in the firm conviction that Luther’s nation, which is religious through and through, will understand me.

So far I have never gone against my conscience and will not do it now either. Therefore, no deletions will be made.[22]

Hedin later published this book in Sweden.[23]

Efforts on behalf of deported JewsAfter he refused to remove his criticism of National Socialism from his book Deutschland und der Weltfrieden, the Nazis confiscated the passports of Hedin's Jewish friend Alfred Philippson and his family in 1938 in order to prevent their intended departure to American exile and retain them in Germany as a bargaining chip when dealing with Hedin. The consequence was that Hedin expressed himself more favorably about Nazi Germany in his book Fünfzig Jahre Deutschland, subjugated himself against his conscience to the censorship of the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, and published the book in Germany.On 8 June 1942, the Nazis increased the pressure on Hedin by deporting Alfred Philippson and his family to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. By doing so, they accomplished their goal of forcing Hedin against his conscience to write his book Amerika im Kampf der Kontinente in collaboration with the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda and other government agencies and to publish it in Germany in 1942. In return, the Nazis classified Alfred Philippson as “A-prominent” and granted his family privileges which enabled them to survive.

For a long time Hedin was in correspondence with Alfred Philippson and regularly sent food parcels to him in Theresienstadt concentration camp. On 29 May 1946, Alfred Philippson wrote to him (translation, abbreviated quotation):

My dear Hedin! Now that letters can be sent abroad I have the opportunity to write to you…. We frequently think with deep gratitude of our rescuer, who alone is responsible for our being able to survive the horrible period of three years of incarceration and hunger in Theresienstadt concentration camp, at my age a veritable wonder. You will have learned that we few survivors were finally liberated just a few days before our intended gassing. We, my wife, daughter and I, were then brought on 9–10 July 1945 in a bus of the city of Bonn here to our home town, almost half of which is now destroyed….

Hedin responded on 19 July 1946 (translation, abbreviated quotation):

…It was wonderful to find out that our efforts were not in vain. In these difficult years we attempted to rescue over one hundred other unfortunate people who had been deported to Poland, but in most cases without success. We were however able to help a few Norwegians. My home in Stockholm was turned into something like an information and assistance office, and I was excellently supported by Dr. Paul Grassmann, press attaché in the German embassy in Stockholm. He too undertook everything possible to further this humanitarian work. But almost no case was as fortunate as yours, dear friend! And how wonderful, that you are back in Bonn….[24]

The names and fates of the over one hundred deported Jews whom Hedin tried to save have not yet been researched.

Efforts on behalf of deported NorwegiansHedin supported the cause of the Norwegian author Arnulf Øverland and for the Oslo professor of philology and university director Didrik Arup Seip, who were interned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He achieved the release of Didrik Arup Seip, but his efforts to free Arnulf Øverland were unsuccessful. Nevertheless, Arnulf Øverland survived the concentration camp.

Efforts on behalf of Norwegian activistsAfter the third senate of the highest German military court (Reichskriegsgericht) in Berlin condemned to death for alleged espionage the ten Norwegians Sigurd Jakobsen, Gunnar Hellesen, Helge Børseth, Siegmund Brommeland, Peter Andree Hjelmervik, Siegmund Rasmussen, Gunnar Carlsen, Knud Gjerstad, Christian Oftedahl and Frithiof Lund on 24 February 1941, Hedin successfully appealed via Colonel General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst to Adolf Hitler for their reprieve. Their death penalty was converted on 17 June 1941 by Adolf Hitler to ten years forced labor. The Norwegians Carl W. Mueller, Knud Naerum, Peder Fagerland, Ottar Ryan, Tor Gerrard Rydland, Hans Bernhard Risanger and Arne Sørvag who had been condemned to forced labor under the same charge received reduced sentences at Hedin's request. Unfortunately, Hans Bernhard Risanger died in prison just a few days before his release.

Von Falkenhorst was condemned to death, by firing squad, by a British military court on August 2, 1946, because of his responsibility for passing on a Führerbefehl called the Commando Order. Hedin intervened on his behalf, achieving a pardon[clarification needed] on December 4, 1946, with the argument that von Falkenhorst had likewise striven to pardon the ten Norwegians condemned to death. Von Falkenhorst's death penalty was commuted by the British military court to 20 years in prison. In the end, Nikolaus von Falkenhorst was released early from the Werl war criminals prison on July 13, 1953.[25]

AwardsBecause of his outstanding services, Hedin was raised to the untitled nobility by King Oskar II in 1902, the last time any Swede was to receive a charter of nobility.[26] Oskar II suggested that he prefix the name Hedin with one of the two common predicates of nobility in Sweden, "af" or "von", but Hedin abstained from doing so in his written response to the king. In many noble families in Sweden, it was customary to do without the title of nobility. The coat of arms of Hedin, together with those of some two thousand noble families, is to be found on a wall of the Great Hall in Riddarhuset, the assembly house of Swedish nobility in Stockholm's inner city, Gamla Stan.

In 1905, Hedin was admitted to membership in the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and in 1909 to the Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences. From 1913 to 1952 he held the sixth of 18 chairs as an elected member of the Swedish Academy. In this position, he had a vote in the selection of Nobel Prize winners.

He was an honorary member of numerous Swedish and foreign scientific societies and institutions which honored him with some 40 gold medals; 27 of these medals can be viewed in Stockholm in a display case in the Royal Coin Cabinet.

He received honorary doctorates from Oxford (1909), Cambridge (1909), Heidelberg (1928), Uppsala (1935), and Munich (1943) universities and from the Handelshochschule Berlin (1931) (all Dr. phil. h.c.), from Breslau University (1915, Dr. jur. h.c.), and from Rostock University (1919, Dr. med. h.c.).

Numerous countries presented him with medals.[27] In Sweden he became a Commander 1st Class of the Royal Order of the North Star (KNO1kl) with a brilliant badge and Knight of the Royal Order of Vasa (RVO).[1] In the United Kingdom he was named Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire by King Edward VII. As a foreigner, he was not authorized to use the associated title of Sir, but he could place the designation KCIE after his family name Hedin. Hedin was also a Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle.[1]

In his honor have been named a glacier, the Sven Hedin Glacier; a lunar crater Hedin; a species of the flowering plant, Gentiana hedini; the beetles Longitarsus hedini and Coleoptera hedini; a butterfly, Fumea hedini Caradja; a spider, Dictyna hedini; a fossil hoofed mammal, Tsaidamotherium hedini; a fossil Therapsid (a “mammal-like reptile”) Lystrosaurus hedini; and streets and squares in the cities of various countries (for example, “Hedinsgatan” at Tessinparken in Stockholm).

A permanent exhibition of articles found by Hedin on his expeditions is located in the Stockholm Ethnographic Museum.

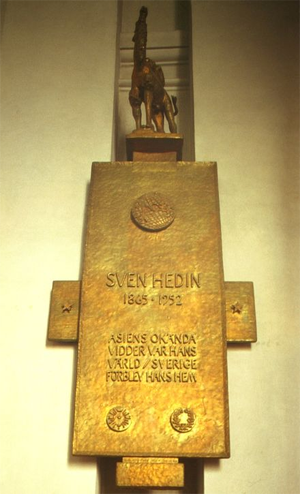

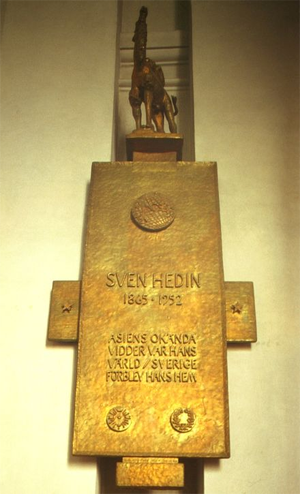

In the Adolf Frederick church can be found the Sven Hedin memorial plaque by Liss Eriksson. The plaque was installed in 1959. On it, a globe with Asia to the fore can be seen, crowned with a camel. It bears the Swedish epitaph:

“ Asia’s unknown expanses were his world—Sweden remained his home. ”

The Sven Hedin Firn in North Greenland was named after him.[28]

Research on Hedin

Source materialA survey of the extensive sources for Hedin research shows that it would be difficult at present to come to a fair assessment of the personality and achievements of Hedin. Most of the source material has not yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny. Even the DFG project Sven Hedin und die deutsche Geographie had to restrict itself to a small selection and a random examination of the source material.

The sources for Hedin research are located in numerous archives (and include primary literature, correspondence, newspaper articles, obituaries and secondary literature).

Memorial plaque with epitaph for Hedin by Liss Eriksson (1959) in the Adolf Fredrik church, Stockholm

Memorial plaque with epitaph for Hedin by Liss Eriksson (1959) in the Adolf Fredrik church, Stockholm• Hedin's own publications amount to some 30,000 pages.

• There are about 2,500 drawings and watercolors, films and many photographs.

• To this should be added 25 volumes with travel and expedition notes and 145 volumes of the diaries he regularly maintained between 1930 and 1952, totaling 8,257 pages.

• The extensive holdings of the Hedin Foundation (Sven Hedins Stiftelse), which holds Hedin effects in trust, are to be found in the Ethnographic Museum and in the National Archives in Stockholm.

• Hedin's correspondence is in the archive of the German Foreign Office in Bonn, in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz, at the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography[29] in Leipzig, and above all in the Ethnographic Museum and in the National Archives in Stockholm. Most of the correspondence in Hedin's estate is in the National Archives and accessible to researchers and the general public. It includes about 50,000 letters organized alphabetically according to country and sender as well as some 30,000 additional unsorted letters.

• The scientific effects as well as a collection of newspaper articles about Hedin organized by year (1895–1952) in 60 bound folios can be found in the Ethnographic Museum.

• The finds from Tibet, Mongolia and Xinjiang are, among other places, in Stockholm in the Ethnographic Museum (some 8,000 individual items), in the Institutes of Geology, Minearology and Paleontology of the Uppsala University, in the depots of the Bavarian State Collection of Paleontology and Geology in Munich, and in the National Museum of China, Beijing.

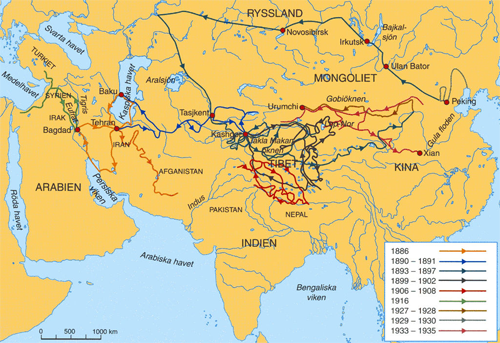

Hedin’s documentationDuring his expeditions Hedin saw the focus of his work as being in field research. He recorded routes by plotting many thousands of kilometers of his caravan itinerary with the detail of a high resolution topographical map and supplemented them with innumerable altitude measurements and latitude and longitude data. At the same time he combined his field maps with panoramic drawings. He drafted the first precise maps of areas unresearched until that date: the Pamir mountains, the Taklamakan desert, Tibet, the Silk Road and the Himalayas. He was likely the first European to recognize that the Himalayas were a continuous mountain range.

He systematically studied the lakes of inner Asia, made careful climatological observations over many years, and started extensive collections of rocks, plants, animals and antiquities. Underway he prepared watercolor paintings, sketches, drawings and photographs, which he later published in his works. The photographs and maps with the highest quality printing are to be found in the original Swedish publications.

Hedin prepared a scientific publication for each of his expeditions. The extent of documentation increased dramatically from expedition to expedition. His research report about the first expedition was published in 1900 as Die geographisch-wissenschaftlichen Ergebnisse meiner Reisen in Zentralasien 1894–97 (Supplement 28 to Petermanns Mitteilungen), Gotha 1900. The publication about the second expedition, Scientific Results of a Journey in Central Asia, increased to six text and two atlas volumes. Southern Tibet, the scientific publication on the third expedition, totalled twelve volumes, three of which were atlases. The results of the Sino-Swedish Expedition were published under the title of Reports from the scientific expedition to the north-western provinces of China under leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin. The sino-Swedish expedition. This publication went through 49 editions.

This documentation was splendidly produced, which made the price so high that only a few libraries and institutes were able to purchase it. The immense printing costs had to be borne for the most part by Hedin himself, as was also true for the cost of the expeditions. He used the fees and royalties which he received from his popular science books and for his lectures for the purpose.

Hedin's Gravestone in the cemetery of Adolf Fredriks church in Stockholm, Sweden

Hedin's Gravestone in the cemetery of Adolf Fredriks church in Stockholm, SwedenHedin did not himself subject his documentation to scientific evaluation, but rather handed it over to other scientists for the purpose. Since he shared his experiences during his expeditions as popular science and incorporated them in a large number of lectures, travelogues, books for young people and adventure books, he became known to the general public. He soon became famous as one of the most well-recognized personalities of his time.

D. Henze wrote the following about an exhibition at the Deutsches Museum entitled Sven Hedin, the last explorer:

He was a pioneer and pathfinder in the transitional period to a century of specialized research. No other single person illuminated and represented unknown territories more extensively than he. His maps alone are a unique creation. And the artist did not take second place to the savant, who deep in the night rapidly and apparently without effort rapidly created awe inspiring works. The discipline of geography, at least in Germany, has so far only concerned itself with his popularized reports. The consistent inclusion of the enormous, still unmined treasures in his scientific work are yet to be incorporated in the regional geography of Asia.

Current Hedin researchA scientific assessment of Hedin's character and his relationship to National Socialism was undertaken at Bonn University by Professor Hans Böhm, Dipl.-Geogr. Astrid Mehmel and Christoph Sieker M.A. as part of the DFG Project Sven Hedin und die deutsche Geographie (Sven Hedin and German Geography).

Literature

Primary

Scientific documentation• Sven Hedin: Die geographisch-wissenschaftlichen Ergebnisse meiner Reisen in Zentralasien 1894–97. Supplementary volume 28 to Petermanns Mitteilungen. Gotha 1900.

• Sven Hedin: Scientific results of a journey in Central-Asia. 10 text and 2 map volumes. Stockholm 1904–1907. Volume 4

• Sven Hedin: Trans-Himalaya: Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, Volume 1 1909 VOL. II

• Sven Hedin: Southern Tibet. 11 text and 3 map volumes. Stockholm 1917-1922.

• Reports from the scientific expedition to the north-western provinces of China under leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin. The sino-Swedish expedition. Over 50 volumes to date, contains primary and secondary literature. Stockholm 1937 ff.

• Sven Hedin: Central Asia atlas. Maps, Statens etnografiska museum. Stockholm 1966. (appeared in the series Reports from the scientific expedition to the north-western provinces of China under the leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin. The sino-Swedish expedition; Ausgabe 47. 1. Geography; 1)

• Sven Anders Hedin, Folke Bergman (1944). History of the expedition in Asia, 1927-1935, Part 3. Stockholm: Göteborg, Elanders boktryckeri aktiebolag. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

• Central Asia and Tibet: Towards the Holy City of Lassa, Volume 1

• THROUGH ASIA

• Through Asia, Volume 1

German editionsa) Biography

• Verwehte Spuren. Orientfahrten des Reise-Bengt und anderer Reisenden im 17. Jahrhundert, Leipzig 1923.

b) Popular works

• Durch Asiens Wüsten. Drei Jahre auf neuen Wegen in Pamir, Lop-nor, Tibet und China, 2 vol., Leipzig 1899; neue Ausgabe Wiesbaden 1981.

• Im Herzen von Asien. Zehntausend Kilometer auf unbekannten Pfaden, 2 vol., Leipzig 1903.

• Abenteuer in Tibet, Leipzig 1904; new edition Wiesbaden 1980.

• Transhimalaja. Entdeckungen und Abenteuer in Tibet, Leipzig 1909-1912; new edition Wiesbaden 1985.

• Zu Land nach Indien durch Persien. Seistan und Bclutschistan, 2 vol., Leipzig 1910.

• Von Pol zu Pol, 3 vol., Leipzig 1911-1912; new edition Wiesbaden 1980.

• Bagdad - Babylon - Ninive, Leipzig 1918

• Jerusalem, Leipzig 1918.

• General Prschewalskij in Innerasien, Leipzig 1922.

• Meine erste Reise, Leipzig 1922.

• An der Schwelle Innerasiens, Leipzig 1923.

• Mount Everest, Leipzig 1923.

• Persien und Mesopotamien, zwei asiatische Probleme, Leipzig 1923.

• Von Peking nach Moskau, Leipzig 1924.

• Gran Canon. Mein Besuch im amerikanischen Wunderland, Leipzig 1926.

• Auf großer Fahrt. Meine Expedition mit Schweden, Deutschen und Chinesen durch die Wüste Gobi 1927- 1928, Leipzig 1929.

• Rätsel der Gobi. Die Fortsetzung der Großen Fahrt durch Innerasien in den Jahren 1928-1930, Leipzig 1931.

• Jehol, die Kaiserstadt, Leipzig 1932.

• Die Flucht des Großen Pferdes, Leipzig 1935.

• Die Seidenstraße, Leipzig 1936.

• Der wandernde See, Leipzig 1937.

• "Im Verbotenen Land, Leipzig 1937

c) Political works• Ein Warnungsruf, Leipzig 1912.

• Ein Volk in Waffen, Leipzig 1915.

• Nach Osten!, Leipzig 1916.

• Deutschland und der Weltfriede, Leipzig 1937 (unlike its translations, the original German edition of this title was printed but never delivered; only five copies were bound, one of which is in the possession of the F. A. Brockhaus Verlag, Wiesbaden).

• Amerika im Kampf der Kontinente, Leipzig 1942

d) Autobiographical works• Mein Leben als Entdecker, Leipzig 1926.

• Eroberungszüge in Tibet, Leipzig 1940.

• Ohne Auftrag in Berlin, Buenos Aires 1949; Tübingen-Stuttgart 1950.

• Große Männer, denen ich begegnete, 2 volumes, Wiesbaden 1951.

• Meine Hunde in Asien, Wiesbaden 1953.

• Mein Leben als Zeichner, published by Gösta Montell in commemoration of Hedin's 100th birthday, Wiesbaden 1965.

e) Fiction• Tsangpo Lamas Wallfahrt, 2 vol., Leipzig 1921-1923.

Most German publications on Hedin were translated by F.A. Brockhaus Verlag from Swedish into German. To this extent Swedish editions are the original text. Often after the first edition appeared, F.A. Brockhaus Verlag published abridged versions with the same title. Hedin had not only an important business relationship with the publisher Albert Brockhaus, but also a close friendship. Their correspondence can be found in the Riksarkivet in Stockholm. There is a publication on this subject:

• Sven Hedin, Albert Brockhaus: Sven Hedin und Albert Brockhaus. Eine Freundschaft in Briefen zwischen Autor und Verleger. F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1942.

Bibliography• Willy Hess: Die Werke Sven Hedins. Versuch eines vollständigen Verzeichnisses. Sven Hedin – Leben und Briefe, Vol. I. Stockholm 1962. likewise.: First Supplement. Stockholm 1965

• Manfred Kleiner: Sven Anders Hedin 1865–1952 - eine Bibliografie der Sekundärliteratur. Self-published Manfred Kleinert, Princeton 2001.

Biographies• Detlef Brennecke: Sven Hedin mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1986, 1991. ISBN 3-499-50355-7

• Johannes Paul: Abenteuerliche Lebensreise – Sieben biografische Essays. including: Sven Hedin. Der letzte Entdeckungsreisende. Wilhelm Köhler Verlag, Minden 1954, pp. 317–378.

• Alma Hedin: Mein Bruder Sven. Nach Briefen und Erinnerungen. Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1925.

• Eric Wennerholm: Sven Hedin 1865–1952. F. A. Brockhaus Verlag, Wiesbaden 1978. ISBN 3-7653-0302-X

• Axel Odelberg: Äventyr på Riktigt Berättelsen om Upptäckaren Sven Hedin. Norstedts, Stockholm 2008 (new biography in Swedish, 600 pages).

Hedin and National Socialism• Mehmel, Astrid: Sven Hedin und nationalsozialistische Expansionspolitik. In: Geopolitik. Grenzgänge im Zeitgeist Bd. 1 .1 1890 bis 1945 ed. by Irene Diekmann, Peter Krüger und Julius H. Schoeps, Potsdam 2000, pp. 189–238.

• Danielsson, S.K.: The Intellectual Unmasked: Sven Hedin's Political Life from Pan-Germanism to National Socialism. Dissertation, Minnesota, 2005.

References1. Wennerholm, Eric (1978) Sven Hedin - En biografi, Bonniers, Stockholm ISBN 978-9-10043-621-6

2. Hedin, Anders Sven (1911) Från pol till pol: genom Asien och Europa, Bonnier, Stockholm OCLC 601660137

3. Sven Anders Hedin; Nils Peter Ambolt (1966) Central Asia Atlas, Statens etnografiska museum, Stockholm OCLC 240272

4. David Nalle (June 2000). "Book Review - Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia". Middle East Policy. Washington, USA: Blackwell Publishers. VII (3). ISSN 1061-1924. Archived from the original on 29 November 2008.

5. "The Sven Hedin Foundation". Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

6. Liukkonen, Petri. "Sven Hedin". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014.

7. Bruno Baumann: Karawane ohne Wiederkehr. Das Drama in der Wüste Takla Makan. München 2000, pp. 113–121, 203, 303–307

8. Bernd Liebner: Söhne der Wüste - Durch Gobi und Taklamakan, Documentary film

9. Referred also as Konqi-, Kongque, Kontsche- or Konche-darja or Peacock River— see also note in Korla and Kaidu River

10. Sven Anders Hedin (1936). The flight of "Big Horse": the trail of war in Central Asia. E. P. Dutton and co., inc. p. 84. Retrieved 18 January 2012. amusing to listen to his outspoken but untruthful conversation... he said ...The whole country in that quarter, Tian-shan-nan-lu, acknowledged the rule of General Ma Chung-yin. General Ma Yung-chu had ten thousand cavalry under his orders, and the total strength of the Tungan cavalry was twice that number

11. Sven Anders Hedin (1940). The wandering lake. Routledge. p. 24. Retrieved 18 January 2012. their object had been to cut us off. A month had not passed since our motor convoy had been cut off by Tungan cavalry, who had fired on it with their carbines. Were we now to be stopped and fired at on the river too? They might be marauders from Big Horse's broken army, out looting, and

12.

http://orient4.orient.su.se/personal/to ... kare_2.pdf[permanent dead link]

13. Verified sources: Sven Hedins in the Stockholm Riksarkivet archived correspondence with Hans Draeger, Wilhelm Frick, Joseph Goebbels, Paul Grassmann and Heinrich Himmler

14. Lubrich, Oliver, ed. (2012). "Sven Hedin". Travels in the Reich, 1933-1945: Foreign Authors Report from Germany (paperback). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0226006451.

15. See letter from Hans Draeger dated 17 January 1942 to Sven Hedin from the Riksarkivet in Stockholm, file: Sven Hedins Arkiv, Korrespondens, Tyskland, 457 and the book by Michael H. Kater: Das "Ahnenerbe" der SS 1935-1945. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-486-56529-X

16. Elisabeth Kraus: Die Universität München im dritten Reich: Aufsätze. Herbert Utz Verlag GmbH, München 2006. pp. 494–502

17. See file R 135 of the Bundesarchivs, located in the Dienststelle Berlin-Lichterfelde

18. Oscar Luis Rigiroli (1017). Historias Secretas de Amor y Sangre (in Spanish). Oscar Luis Rigiroli. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018 – via PublishDrive.. The present source is an historical-based fictional-novelist book, but he is the publisher of the '"Daurio 2018"'s reference, with a coherent content.

19. Cêdric Daurio (2018). The mystic warrior. Oscar Luis Rigiroli. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018 – via PublishDrive.

20. Giorgio Galli. Hitler and the magic Nazism (Hitler e il Nazismo magico).

21. In: Abenteuerliche Lebensreise, p. 367

22. As yet unpublished letters from the Riksarkivet in Stockholm, file of Heinrich Himmler: Sven Hedins Arkiv, Korrespondens, Tyskland, 470. The orthography and punctuation were updated

23. On this matter there is a thorough investigation contained in the essay Sven Hedin und nationalsozialistische Expansionspolitik by Astrid Mehmel loc.cit.

24. As yet unpublished letters from the Riksarkivet in Stockholm, file: Sven Hedins Arkiv, Korrespondens, Tyskland, 487

25. cf. Sven Hedin's German Diary 1935–1942, Dublin 1951, S. 204–217 und Eric Wennerholm, Sven Hedin 1865–1952, S. 229–230

26. "The Swedish Way". Swedish Heraldry Society. 23 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 November 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

27. cf. Christian Thorén: Upptäcktsresanden Sven Hedins ordenstecken i Kungliga Livrustkammarens samlingar. In: Livrust Kammaren. Journal of the Royal Armoury 1997-98. Stockholm. pp. 91-128. ISSN 0024-5372. (Swedish text with English picture captions and English summary, color illustrations of Sven Hedin’s medals and decorations, literature)

28. Sven Hedin Firn, Army Map Service, United States Army Corps of Engineers, Greenland 1:250,000

29. Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography

Further reading• Meyer, Karl E.; Brysac, Shareen Blair (25 October 1999). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-58243-106-2.

• Sven Anders Hedin, Folke Bergman (1944). History of the expedition in Asia, 1927-1935, Part 3. Stockholm: SLANDERS BOKTRYCKERI AKTIEBOL AG G6TEBORG. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

• Hedin, Sven; foreword by John Hare (2009). The Silk Road: Ten Thousand Miles through Central Asia. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-84511-898-3.

• Tommy Lundmark (2014) Sven Hedin institutet. En rasbiologisk upptäcksresa i Tredje riket. ISBN 9789186621957) (Swedish)

External links• Works by Sven Hedin at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Sven Hedin at Internet Archive

• Scanned works

• Excellent bibliography, listing publications and further literature

• International Dunhuang Project Newsletter Issue No. 21, article on Sven Hedin, available also as PDF

• "Hedin, Sven Anders" . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

• British Indian intelligence on Sven Hedin. National Archives of India (1928)

• Newspaper clippings about Sven Hedin in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW