by Peter Fimrite

SFGate

Published 4:00 am PST, Tuesday, February 10, 2009

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

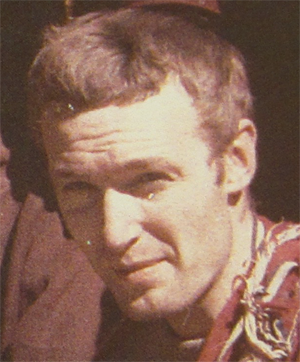

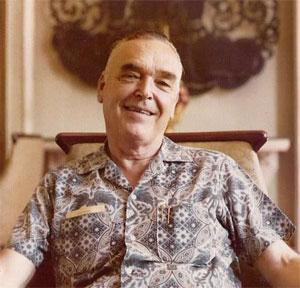

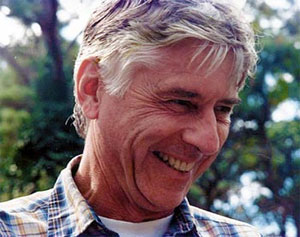

Taken about 1986. obit photo of Francis Macy, dedicated environmentalist, energy activist and citizen diplomat, whose ground-breaking work inspired fresh collaborative ventures with the former Soviet Union, died unexpectedly of an apparent heart attack in Berkeley on January 20th at age 81. Photo: Family Photo, Courtesy Photo

A memorial service will be held on Feb. 21 for Francis Underhill Macy, an environmental activist and expert on Russian culture who dedicated much of his life as a citizen diplomat working to improve relations with people in the former Soviet Union.

Mr. Macy, who advocated for racial equality long before the civil rights movement and was a well-known opponent of nuclear proliferation, died Jan. 20 in his Berkeley home from a heart attack. He was 81.

Born in Evanston, Ill., he was the youngest of four brothers whose parents were involved in the theater. Known to everyone as Fran, he received a bachelor's degree in government in 1949 from Wesleyan University, where he also excelled as an actor.

The course of his life began to take shape at Wesleyan, where he did what was, at the time, almost unthinkable. He became roommates with a black man named Chuck Stone, who would become a prominent journalist.

The two men worked together at one point trying to desegregate restaurants in Washington, D.C., and became lifelong friends.

After graduation, he enrolled at Harvard, where he turned heads rooming with another African American. He received a master's in 1951 in Slavic studies at Harvard and learned to speak Russian.

In 1953, he married Joanna Rogers, who embraced her husband's activism and remained his compatriot for life.

He began working for the Russian-language station Radio Liberty, which was based in Munich, at the height of the Cold War. He worked for the U.S. Information Service, which sent American citizen diplomats around the world to talk to people about American values and democracy.

The NSC's Project Democracy

Efforts to create "political development" programs date back to the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, when Congress discussed, but declined to approve, several bills to establish a "Freedom Academy" that would conduct party-building in the Third World. The passage of the Title IX addition to the Foreign Aid Act in 1966 spurred renewed interest in such an agency. The Brookings Institute, one of the most important policy planning institutes, undertook an extensive research program on political development programs in coordination with the AID and other government agencies.37 In 1967, President Johnson appointed the three-member Katzenback Commission which recommended that the government "promptly develop and establish a public-private mechanism to provide public funds openly for overseas activities of organizations which are adjudged deserving, in the national interest, of public support."38 A bill was introduced in Congress in 1967 by Rep. Dante Fascell (D.-Fla.) to create an "Institute of International Affairs," but it was not approved.39 Meanwhile, the public outcry against intervention abroad in the early 1970s as a result of the Indochina war and the revelations of CIA activities, as well as the Watergate scandal, put these initiatives on hold for much of that decade.

Then, in 1979, with reassertionism taking hold, a group of government officials, academicians, and trade union, business, and political leaders connected to the foreign-policy establishment, created the American Political Foundation (APF), with funding from the State Department's United States Information Agency (USIA) and from several private foundations. The APF brought together representatives of all the dominant sectors of US society, including both parties and leaders from labor and business. It also brought together many of the leading figures who had been developing the ideas of the new political intervention, many of them associated with the transnationalized fraction of the US elite.40 Among those on the APF board were Lane Kirkland of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), former Republican National Committee chair William Brock, former Democratic National Committee chair Charles Manatt, international vice-president for the US Chamber of Commerce Michael Samuels, as well as Frank Fahrenkopf, Congressman Dante Fascell, Zbignew Brezezinski, John Richardson, and Henry Kissinger. The APF was chaired by Allen Weinstein, who would later become the first president of the NED. The names of APF activists and the composition of the APF board are revealing. They fall into three categories. One is members of the inner circle of second-generation post-World War II national security and foreign policymakers, such as Kissinger, Brezezinski, and Richard Allen, all former National Security Advisors. Another is top representatives of the four major constituencies that made up the post-World War II foreign-policy coalition -- the Democratic and Republican parties, labor and business. The third is operatives from the US intelligence and national security community. These intelligence and security operatives include people associated with the CIA and dozens of front organizations or foundations with which it works, as well as operatives from the USIA.

The prominence of the USIA is significant, since this is an agency with a long track record in political and psychological operations. It was created by the Eisenhower administration in 1953 as an agency within the NSC at the recommendation of a top-secret report issued by the President's Committee on International Information Activities. Its explicit purpose was to conduct propaganda, political and psychological operations abroad in conjunction with CIA activities.41 A National Security Action Memo in 1962 stipulated coordination among the USIA, the AID, the CIA, the Pentagon, and the State Department in waging political warfare operations, including civic action, economic and military aid programs.42 Based on research programs it conducts directly or commissions governmental and non-governmental agencies to conduct, the USIA selects propaganda themes, determines target audiences, and develops comprehensive country plans for media manipulation and communications programs. As part of Project Democracy, USIA activities were greatly expanded in the 1980s.43

The APF recommended in 1981 that a presidential commission examine "how the US could promote democracy overseas." The White House approved the recommendation for Project Democracy. At its onset, Project Democracy was attached to the NSC, and supervised by Walter Raymond Jr., a high-ranking CIA propaganda specialist who worked closely with Oliver North, a key player in the Iran-Contra scandal, on covert projects.44 "Overt political action," explained Raymond, could help achieve foreign-policy objectives by providing "support to various institutions [and]... the development of networks and personal relationships with key people."45 Raymond explained that the creation of the NED as a "vehicle for quasi-public/private funds" would fill a "key gap" in US foreign-policy -- it would be a "new art form."46 Raymond and his staff at the NSC worked closely with Democratic Congressman Dante Fascell of Florida. Fascell chaired the House Foreign Affairs Committee which would draft the legislation creating the NED and organized support for the project within Congress.47

In June 1982, in a speech before the British parliament considered the symbolic inauguration of the new policy, Ronald Reagan announced that the United States would pursue a major new program to help "foster the infrastructure of democracy around the world."48 A secret White House memo on the minutes of a Cabinet-level planning meeting to discuss Project Democracy held two months later, in August, set the agenda: "We need to examine how law and Executive Order can be made more liberal to permit covert action on a broader scale, as well as what we can do through substantially increased overt political action."49 Then, in January 1983, Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive 77 (NSDD 77), which laid out a comprehensive framework for employing political operations and psychological warfare in US foreign policy. At least $65 million was allocated by the administration to underwrite the activities and programs contemplated in the NSC directive.50 NSDD 77 focused on three aspects of Project Democracy.51 One aspect was dubbed "public diplomacy" -- psychological operations aimed at winning support for US foreign policy among the US public and the international community -- and involved an expansion of propaganda and informational and psychological operations. The directive defined "public diplomacy" as "those actions of the US Government designed to generate support for our national security objectives." An Office of Public Diplomacy (OPD) operating out of the White House was established.52 The General Accounting Office ruled OPD an illegal domestic propaganda operation in 1988. Another aspect set out in the NSC directive was an expansion of covert operations. This aspect would develop into the clandestine, illegal government operations later exposed in the hearings on the Iran-Contra scandal of the late 1980s. Parallel to "the public arm of Project Democracy, now known as the National Endowment for Democracy," noted the New York Times, "the project's secret arm took an entirely different direction after Lieut.-Col. Oliver I. North, then an obscure National Security Council aide, was appointed to head it."53

The final aspect was the creation of a "quasi-governmental institute." This would engage in "political action strategies" abroad, stated NSDD 77.54 This led to the formal incorporation of the NED by Congress in November 1983. While the CIA and the NSC undertook "covert" operations under Project Democracy, some of which were exposed in the Iran-Contra investigations, the NED and related agencies went on to execute the "overt" side of what the New York Times described as "open and secret parts" of Project Democracy, "born as twins" in 1982 with NSDD 77.55 But while the Iran-Contra covert operations that grew out of Project Democracy were exposed and (assumed to be) terminated, the NED was consolidated and expanded as the decade progressed. With the mechanisms in place by the mid-1980s, the "reassertionists" turned to launching their global "democracy offensive." "The proposed campaign for democracy must be conceived in the broadest terms and must weave together a wide range of superficially disparate aspects of US foreign policy, including the efforts of private groups," noted one Project Democracy consultant. "A democracy campaign should become an increasingly important and highly cost-effective component of ... the defense effort of the United States and its allies."56 The countries in which the NED became most involved in the 1980s and early 1990s were those set as priorities for US foreign-policy. "Such a worldwide effort (a 'crusade for democracy'] directly or indirectly must strive to achieve three goals," one Project Democracy participant explained. "The preservation of democracies from internal subversion by either the Right or the Left; the establishment of new democracies where feasible; and keeping open the democratic alternative for all nondemocracies. To achieve each of these goals we must struggle militarily, economically, politically and ideologically."57

In countries designated as hostile and under Soviet influence, such as Nicaragua and Afghanistan, the United States organized "freedom fighters" (anti-government insurgents) in the framework of low-intensity conflict doctrine, while the NED and related organs introduced complementary political programs. Those countries designated for transition from right-wing military or civilian dictatorships to stable "democratic" governments inside the US orbit, including Chile, Haiti, Paraguay, and the Philippines, received special attention. By the late 1980s and early 1990s ,the NED had also launched campaigns in Cuba, Vietnam, and other countries on the US enemy list, and had also become deeply involved in the self-proclaimed socialist countries, including the Soviet Union itself. While these first programs were tied to the 1980s anti-communist crusade, the NED and other "democracy promotion" agencies made an easy transition to the post-Cold War era. As the rubric of anti-communism and national security became outdated, the rhetoric of "promoting democracy" took on even greater significance. Perestroika and glasnost highlighted authentic democratization as an aspiration of many peoples. But US strategists saw in the collapse of the Soviet system an opportunity to accelerate political intervention under the cover of promoting democracy. In the age of global society, the NED and other "democracy promotion" organs have become sophisticated instruments for penetrating the political systems and civil society in other countries down to the grassroots level.

-- Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, U.S. Intervention, and Hegemony, by William I. Robinson

In 1961, Mr. Macy led the first ever citizen diplomatic mission into the USSR. The group of Russian-speaking American graduate students were the first Americans many locals had ever met.

"The word got out and, rain or shine, there were long lines of people waiting to talk to young Americans," said Mr. Macy's wife, who accompanied him on the mission. "It changed their attitude about Americans. They saw for the first time that Americans were real people, not the rich capitalist racists who fit into the Stalinist stereotype."

It was such a moving experience that Mr. Macy turned down a prestigious government posting in Moscow and joined the Peace Corps. He also took time to join the 1963 March on Washington and was there when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have A Dream" speech.

"Fran saw that when you bring people together, magic happens," said his wife.

Between 1964 and 1972, he served as deputy Peace Corps director in India, country director in Tunisia and Nigeria and finally as director of all Peace Corps programs in Africa.

In 1983, Mr. Macy organized an exchange program. He has since taken delegations of educators, environmentalists, psychologists and civic organizers to Russia and the former Soviet republics for talks and professional training.

He got involved in nuclear issues after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, which occurred while he was in Russia. In 1995 he founded the Earth Island Institute's Center for Safe Energy, which has trained hundreds of activists in Russia, Ukraine, Georgia and Kazakhstan.

He and his wife, an activist, author and teacher of Buddhist theory, have been involved in many local environmental groups and causes, including the Nuclear Guardianship Project, the Alliance for Nuclear Accountability and Tri-Valley CARES, a watchdog group at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Besides his wife, he is survived by his sons, Christopher of Amsterdam and Jack of Berkeley; his daughter, Peggy Macy of Berkeley; and three grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Feb. 21 at the First Congregational Church of Berkeley, 2345 Channing Way.