Ceylon's Department of Public Instruction, 1868 [Excerpt]

From Coffee to Tea Cultivation in Ceylon, 1880-1900: An Economic and Social History

by Roland Wenzlhuemer

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

8.5 The Departments

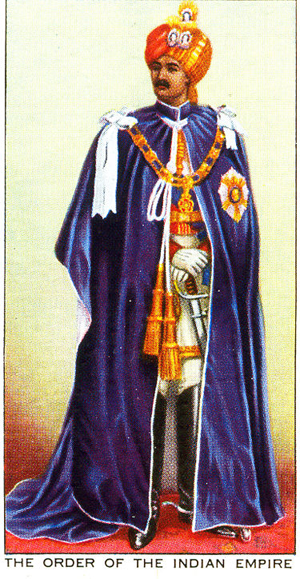

Many of the preferences and goals of an administration are reflected by the number and nature of its departments. In the nineteenth century, the most important departments in Ceylon were the Survey Department, the Public Works Department (PWD), the Department of the Royal Botanical Gardens and the Land Registry Department (alongside the Medical, Police, Customs and Postal Departments common to most administrations). The Survey Department and the PWD were concerned with the improvement of the infrastructure. The Department of the Royal Botanical Gardens (together with Kew Gardens) provided botanical know-how and support to the plantation enterprise. The Land Registry Department occupied itself with the creation of clear titles to land -- a crucial position in a plantation-based economy.

The last decades of the nineteenth century saw a certain diversification of administrative interests and, thus, a reorganisation of the departments. The first measure in that respect was the reorganization of the Police Department in 1865. Hitherto, the Government Agents had been in charge of the police in their province with only a small force of policemen at their direct disposal and relying on the native headmen for much of the work. With overworked GAs and a rising crime rate, this system was not efficient anymore: Consequently, after 1865 police forces were, step by step, stationed in the entire island. The Government Agents still had a small force of policemen at their headquarters, but were relieved of the responsibility for their whole province.74 The Inspector-General of Police, a member of the CCS, now was in charge of the whole police force.

The Department of Public Instruction was founded in the year 1868. As the next chapter thoroughly deals with the development of education and educational policy, reference to the creation of the Department of Public Instruction will be made there.

***

Chapter Nine: Education

9.1 British Educational Policy, 1796-1867

The history of education in nineteenth century Ceylon is closely linked with several other aspects of British policy in the island. In the first place, the state of the government revenue – that itself depended heavily on the fortunes of the plantation industry -- set up the financial framework, within which colonial educational policy could be realised. As the propagation of education has never been a preference of the British administration throughout the nineteenth century, expenditure on educational facilities has often been the first to suffer during times of financial difficulties. Second, the British approach to the education of the Crown's 'native subjects' was only partly based on humanitarian thoughts. Practical considerations constantly influenced education policies. The want of English-speaking clerks for the lower ranks of the administration, for instance, led to an emphasis on English education in the wake of the Colebrooke-Cameron report. Later, the policy was reversed. The administrative machinery could not absorb the newly created English-educated class anymore. Third, the competition of the various religious bodies and groups in Ceylon played a significant role in the development of education in Ceylon. At first, the struggle for predominance in the field of education was mainly a struggle between different Christian missionary societies. Later -- in the course of the so-called 'religious revivals’ that will be discussed in detail in a later chapter -- the representatives of the indigenous religious faiths joined the competition as well.

Until the implementation of the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms in the early 1830s, the propagation of education was largely neglected by the colonial government. When the British took over the Dutch possessions on the island, two separate school system existed. The Dutch had established a network of Christian parish schools that had been under central government control. Outside this system there existed a fairly large number of traditional Buddhist schools. These pansala schools were attached to Buddhist monasteries and managed by the clergy.1 Most of the pansalas were located in the Kandyan highlands (and, therefore, came under British authority only in 1815). The pansala network was less tight in the Maritime Provinces. During the administration of the East India Company from 1796 to 1798, education was not considered particularly important and the Dutch parish schools fell into complete neglect. Only with the arrival of Governor Frederick North in 1798 these schools were revived again and soon stood at the centre of the government's education policy. North -- who is said to have been influenced by religious motives more than by educational ones -- appointed the Colonial Chaplain Rev. James A. Cordiner as Principal of Schools. North and Cordiner showed a keen interest in the establishment of a network or vernacular schools, but in 1803 their ambitions were put to a stop by the Colonial Office's retrenchment policy. The parish schools were abolished on financial grounds and only the English Academy -- established by North as the first English school in Ceylon in 1800 -- survived the cutting back of funds.2

North's successors, Thomas Maitland and Robert Brownrigg, did not revive the parish schools. While Maitiand showed no interest in the propagation of education at all, Brownrigg's Governorship saw the arrival of four important missionary societies on the island. In 18 12, the Baptist Missionary Society came to Ceylon and started to set up missionary schools. The Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society followed in 1814, the American Mission in 1816 and the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in 1818.3 The Wesleyans, the CMS and – on a smaller scale -- the Baptists immediately started to establish schools in the centres of the maritime regions -- preferably in and around Colombo.4 Due to political reasons, the American Mission was not allowed into Colombo and, thus, concentrated solely on missionary activity in the Jaffna peninsula.

The missionary societies regarded education as the principal vehicle of conversion and mainly established vernacular schools to reach the mass of the 'heathens.’ In these schools the local languages -- i.e. Sinhala or Tamil -- were used for the instruction of the pupils.5 Under Brownrigg, the colonial government's education policy confined itself to supporting the activities of the missionary bodies. In 1817, an Archdeaconry (subordinate to Calcutta) was established in Ceylon and the Church of England became the official church of the state. The remaining government schools came under the supervision of the Church of England and its Ecclesiastical Establishment.6

The missionaries were admitted to the Kandyan regions in 1820. After the conquest of Kandy in 1815, the Kandyan Convention had assured British protection to Buddhism, but with the suppression of the Kandyan Rebellion in 1818 a new proclamation was issued that limited government support to Buddhism. Moreover, Brownrigg officially extended government protection to all religions and, therefore, found it possible to open the Kandyan regions to the missionary bodies.7

Thanks to Brownrigg's support, the missionary societies soon occupied a more important position than the government in the spread of education. Under Brownrigg's successor Edward Barnes, the role of the missionaries became even more pronounced as Barnes showed interest only in the economic progress of the island. He did not actively support the missionary societies, but, due to government neglect, he left educational matters almost completely to the churches. Jayaweera states that Barnes "discouraged educational enterprise, state or private, and all but killed state schools; the latter were reduced to four English and ninety parish schools by 1830.”8 When Colebrooke arrived in Ceylon in 1829, the missionary bodies practically controlled the educational system of the island -- partly due to the active support of Brownrigg, partly due to Barnes' indifference.

As he did on most matters of colonial administration, Colebrooke also commented on the prevalent system of education. Sumathipala points out that, when Colebrooke investigated educational matters on the island, only about 800 pupils (out of a total of 26,970) received an English education. About half of those attended the five existing government English schools.9 As Colebrooke occupied a more practical viewpoint concerning the future of education in Ceylon,10 he recommended to discontinue any government activity in the spheres of vernacular education and laid additional emphasis on the importance of English education on the island. In his opinion, the intended opening of the lower ranks of the CCS to the Ceylonese required English-educated personnel. The spread of Western -- i.e. British – ideas and values would unify the island and foster local participation in the administration and judicature.11 Consequently, Governor Horton -- whose task it was to implement most of Colebrooke's recommendations -- closed all government vernacular schools. Furthermore, government English schools were closed in many locations where missionary schools already taught English. Thus, the missionaries were given an additional inducement to engage in English education12 as Colebrooke objected to the missionaries' preference for vernacular education.13 The Archdeacon of the Church of England became the head of the first School Commission in 1834. This commission implemented Colebrooke's recommendations almost to the letter and concentrated entirely on the establishment of English schools.14 The missionary societies soon followed the government policy and laid their emphasis on the foundation of English schools as well.15 The School Commission managed to expand educational facilities (primarily for the teaching of English) in the next years. However, the government schools constantly lost more ground to the rapidly spreading missionary schools.

The School Commission and its policy exclusively represented the Church of England -- the Anglicans. No members of other religious instruction was made a compulsory subject in government schools. Only in 1841 Governor Stewart Mackenzie reorganized the mission and created the Central School Commission. In the new commission Presbyterians, Roman Cathoiics, Wesleyans and Anglicans were all given a voice -- but none of the indigenous religious faiths was represented.16 The creation of the Central School Commission triggered several changes in the educational policy of Ceylon. From 1841 on, government schools were open to children of all Christian denominations. Furthermore, the first grant-in-aid system for nongovernment English schools was introduced and enabled missionary English schools to receive a government grant (provided that they allowed inspection and examination by the commission). As they had a long tradition of English teaching, schools in Jaffna made particular use of the grant-in-aid system and, consequently, several government schools in the peninsula were closed down.17

The Wesleyan Rev. William Gogerly presided the commission from 1843 onwards and implemented a comparatively progressive policy. Together with Governor Colin Campbell he introduced several new schemes. In 1843, the Central School Commission made provisions for vernacular education in elementary schools. In 1845, a Native Normal School for the training of teachers in vernacular education was established. Two years later, 30 vernacular schools were opened.18 As a consequence, government expenditure on education rose from £2,999 in the year 1841 to £11,4-15 in 1847 19 (i.e. from 0.8% to 2.2% of the total expenditure).20

In the course of the first serious coffee crisis in 1848 and the following financial depression, government expenditure on education was drastically reduced. Vernacular education suffered hardest. Although most government vernacular schools continued to exist, the introduction of fees and the closing down of the Native Normal School prevented further progress in vernacular education.21 The neglect of education policy continued when the depression had been overcome and the coffee mania of the 1850s had set in. Economic advance and the improvement of the infrastructure were the sole interest of the administration during that time. Without government guidance the policy of the Central School Commission changed almost every year during the 1850s -- laying emphasis on English education in one year and promoting vernacular instruction in the next.22 Education, therefore, remained largely the domain of the missionary bodies. The Christian supremacy in the field was underlined by the Central School Commission's policy to give grants exclusively to schools run by Christian institutions.23 No pansala or other non-Christian school had ever received a grant so far.

In the 1860s, the Roman Catholic community -- led by the Archbishop of Colombo Christopher Bonjean -- put up first resistance to the prevailing system. When the Tamil MLC Muttu Coomaraswamy (backed by the Burgher MLC Martenz) requested the creation of a special committee to investigate the matter, a Subcommittee of the Legislative Council was eventually appointed to conduct inquires about the state of education in Ceylon.24 In 1865, the Morgan Committee -- named after its president, Queen's Advocate Richard F. Morgan -- took up its work.

9.2 The Morgan Committee and the Department of Public Instruction

The Morgan Committee presented its final report in 1867. The implementation of its proposals not only placed the administration of education on a sound institutional footing but also led to a reversal of government educational policy on the island. Of the various changes advocated by the Committee only three major points shall be discussed here: the establishment of the Department of Public Instruction, the emphasis on vernacular education and the introduction of the so-called Denominational System based on a revised grant-in-aid system. Governor Hercules Robinson said in an address to the Legislative Council in 1870:

I have to announce to you the adoptions of a distinct policy the tendency of which will be to extend the operations of government in the direction of establishing village schools as yet unprovided with the means of instruction, but gradually to contract its operations in respect of English schools in the lawn districts where an effective system of grant-in-aid will enable the government to employ its funds to much greater advantage than in maintaining schools of its own.25

From 1869/70 onwards, the Committee's proposals were gradually realised. The Morgan Report expressed the opinion that the government had an obligation to spread (vernacular) education in the entire island. It has been said that the Committee's views had not so much been shaped by the needs of the population but "by the current trends in England and India which favoured some form of state responsibility for education."26 Accordingly, vernacular education gained new momentum with the implementation of the Report's proposals. The number of government vernacular schools increased from 64 in 1869 to 347 in 1881.27 The report also proposed the abolition of government English elementary schools on the assumption that superior (i.e. English) education was only required by a small minority of the population. Superior Central schools -- already existent in some of the population centres -- and Anglo-vernacular schools28 [28. In Anglo-vernacular schools English was not the medium of instruction, but merely a subject. The pupils learned English with explanations and instructions given in the vernacular.] should provide the necessary facilities for those who could afford an English education. All school fees for vernacular education were abolished, whereas superior English education was only available against the payment of substantial fees.29 Wickremeratne even holds that it was one of the main goals of the colonial government's educational policy after 1867 to retain the growing educational gap.30

The inefficiency of the Central School Commission was demonstrated by its last report of the year 1867. The report showed that since 1840 only 86 new schools had been established.31 The Morgan Committee decided to do away with the Commission and create the Department of Public Instruction. The Governor, the Executive Council and the School Commission suggested the additional creation of an advisory board -– consisting of representatives of all races and denominations -– to control and assist the Director of Public Instructions. But Morgan opposed this view, and, on his advice, the Legislative Council voted against the establishment of such a board.32 Consequently, the Director of Public Instruction was directly and solely responsible for the implementation of the government's educational policy.

After 1867 the management of many government English schools was handed over to the missionary societies. Other schools were simply closed when missionary English schools existed in the vicinity. The government followed this policy without consideration of the religious feelings of the population.33 The measures of the Morgan Report provided no conscience clause that could exempt Buddhist or Tamil pupils from the compulsory attendance of religious instruction. Due to the government's gradual retreat from English education and the promotion of missionary English schools, everybody with a desire to learn English was exposed to the proselytising ambitions of the missionaries. Sumathipala quotes Ponnambalam Ramanathan who in 1884 presented a memorial of several Jaffna Hindus to the Legislative Council, in which the petitioners complained about the religious intolerance in the missionary schools:

[C]hildren who are obliged to go to these missionary schools are forced by the missionaries, under pain of fines and expulsion, to read the Bible whether they liked it or not [ ... ] Hindu boys who, for want of their own English schools, resort to the missionary schools, have learnt to make mental reservations and are getting skilled in the art of dodging. The holy ashes put on at home during worship are carefully rubbed off as they approach the Christian school and they affect the methods of Christian boys while at school. [ ... ] There is a great deal too much of hypocrisy in Jaffna in the matter of religion, owing the fact that the love of the missionaries for proselytes is as boundless as the love of the Jaffnese to obtain some knowledge of English at any cost. […] If there is no conscience clause in the grant-in-aid code, I think the sooner a clause of that kind is introduced the better it will be for religious freedom in Ceylon.34

While religious instruction was not a subject in government schools anymore, the private grant-receiving schools were free to teach the subject. Almost all of the grant-aided schools were under Christian management and, thus, held compulsory religious instruction lessons (mostly held in the first school hour). Throughout the nineteenth century, the pupils were compelled to attend these lessons. No conscience clause existed.

The government's gradual retreat from English education gained momentum, when the plantation economy experienced first signs of the coffee crisis in the late 1870s. Government coffers suffered from a lack of funds. Thus, the Legislative Council's Retrenchment Committee proposed in 1883 to hand over local Anglo-vernacular and English schools to the Municipal and Local Boards. Ordinance 33 of 1883 was passed and made provisions for the transfer of English and mixed schools located within the limits of municipalities to the local authorities. But only in Puttalam such a transfer was successful. Most other Municipal and Local Boards lacked the financial means to assume control over the government schools. The missionaries stepped in and took over the management of the schools. Therefore, 21 government English schools were either handed over to the missionary bodies or closed until the end of 1884.37 The Colombo Academy (renamed the Royal College in 1881) remained the only government English school within the boundaries of a municipality.38 The government's vernacular education policy was more successful. Between 1873 and 1900, the number of government vernacular schools increased from 241 to 484. Still the government was outperformed by the missionaries who increased the number of their schools from 237 to 1,186.39 Jayasuriya states that on several recorded occasions government vernacular schools were also handed over to the missionaries or closed, if a missionary school of the same type was near.40

The government relied heavily on the grant-in-aid system introduced by the Morgan Report and considered it a practicable way to outsource educational responsibility to the missionaries. The allocation of such grants was based on the principal of payment by results. Officials of the Department of Public Instruction conducted examinations in the schools. The results of these examinations decided whether a school was eligible for a grant and, if so, for what grant category. The grant in-aid system did not place any restriction on religious instruction in the grant-aided schools -- although examinations were conducted in secular subjects only. Grants were given in the categories A, B and (since 1872) C -- in descending order of the allocated sum. Grants for C schools were small and awarded only for three years. During that time the C school had to qualify for an A or B grant. The distinction in A, B and C schools was applied to every type of school. Among those types English schools received the highest grants, followed by Anglo-vernacular and, finally, vernacular schools.41

The working of the grant-in-aid system was tightly connected with the financial state of the colony. Initially comparatively generous grants were made. The coffee plantations' prosperity had reached new heights and the government coffers were filled up to the rim. The missionary societies seized the opportunity and most missionary schools applied for a grant. In 1870, the first year of the new scheme, 223 schools received a grant. Six year later the number of eligible schools had increased to 697.42

The government and the Department for Public Instruction were both pleased with the working of the grant-in-aid system from its very inception. More and more educational responsibility was passed to the private missionary bodies that competed fiercely for grants and constantly established more schools. The missionaries were the main beneficiaries of the system-- even though, in theory, all private schools (i. e. not just missionary schools) could apply for a government grant since the revisions of the Morgan Committee.Although the indigenous religious groups quickly realised the potential of the grant-in-aid system, they could not make full use of the scheme due to several hindrances. Unlike their Christian counterparts, the Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims had not participated in the field of education prior to the 1870s on any significant scale. The considerable number of Buddhist pansala schools had existed outside the official educational system of the island since the arrival of the British. The pansalas contributed to the spread of literacy in the vernacular and were very valuable for the villagers, but they worked on different principles than government or missionary schools. Therefore, they could not serve as a training ground in (Western) educational management. Apart from the Buddhist pansalas, the indigenous communities had little experience in the management of schools, although every now and then a local school was set up and run on private funds.

The indigenous religion groups' ambitions to secure government grants did not only suffer from their lack of experience in schools management. The often also lacked the money to set up schools in the first place. And when they managed to do so, they faced the fierce opposition of the missionary bodies, the partiality of the British officials and -- the most formidably -- provisions of the so-called Distance Rule as introduced in 1874. Thus, only four Buddhist and one Hindu school were registered for a grant in the year 1880 (ten years after the introduction of the revised scheme) -- as against a total of 833 grant-aided schools in that year.43

The missionary societies with their headquarters in Europe or America had much larger financial resources at their disposal than the local Buddhist or Hindu communities. This gave the missionaries a distinct advantage over their native competitors, as the initial investment to set up and run a school was considerable and grants were only given to schools already up and running. Furthermore, the opposition of the missionaries and their influence on the European officials often delayed or prevented the registration of Buddhist and Hindu schools for a grant. Jayasuriya gives several examples for this practice and both Jayasuriya and Sumathipala quote the Director of Public Instruction on one particular case in the Northern Province:

During the last two years some applications were considered for the registration of schools under Sivite [Hindu] managers. They were large schools, had existed for many years, and fulfilled every condition required by the existing regulations. The case of one of the schools was submitted to my particular attention by the Tamil members of the Legislative Council. The protests of one of the Managers against the registration of such schools has been of a very determined kind, and he directly claims for the Society he represents the 'exclusive possession' of the district in which his schools are situated. Indeed with reference to a school which had been in existence for nearly twenty years, he says,'If it can be made plain that the school is really needed, the teacher should be required to accept Mission management as the sole condition to receiving government aid.'44

Only rarely did such cases reach the Director of Public Instruction -- and even then it seems that little has been done to keep the Christian missionaries from interfering. The school in the referred case did not receive the grant.45 Christian lobbying slowed down the development of native schools and, above all, increased the lead of the missionary societies in the educational field. And with the introduction of the Distance Rule in 1874 an additional and crucial advantage in the competition for grants was given to those bodies with a large number of already registered schools -- i.e. the Christian missionary societies. The new rule made provisions for the refusal of grants for schools established within three miles of an existing government or grant-in-aid school of the same type -- except in special circumstances.46 Taking into account that the missionary schools had right from the introduction of the grant-in-aid scheme seized the opportunity and established numerous schools, it becomes clear that such a rule prevented the registration of new schools in many localities. The existence of a government or missionary grant-aided school in a village (or in the vicinity thereof) made the allocation of a grant for another school in that area impossible. This served a severe blow to the Buddhist and Hindu schools that explicitly aimed at providing indigenous educational facilities as alternative to the already established missionary institutions. With 595 grant-in-aid schools in 1874 47 (and the number rapidly increasing) it was hard enough to find a suitable place for a school with no other grant-in-aid school already existent. In the important population centres, where numerous missionary schools competed for pupils, the registration of a grant-aided school was almost impossible. The working of the Distance Rule satisfied both the secular authorities (for financial considerations) and the Protestant missionaries (whose educational supremacy it safeguarded). The Distance Rule was, therefore, included in Bruce's Revised Code of 1880. And in 1891, the even more restrictive quarter-mile rule was introduced.

9.3 Education, 1880-1900

Since the mid-1870s, the government and its Department of Public Instruction tried to keep expenditure on education outside the grant-in-aid system as low as possible. Even within the grant-in-aid system steps were taken to check the expansions of the scheme and to prevent the allocation of government funds to non-Christian bodies. The Distance Rule of 1874 is the best example for that policy. However, the adopted measures did not immediately lead to a reduction of expenditure in education. But during the peak of the coffee crisis in the early years of the 1880s, severe cutbacks in government expenditure had to be made and the education funds were chosen as one field of reduction.

When the government instructed Charles Bruce, the Director of Public Instruction, to compile a thoroughly revised code for schools in 1879, the upcoming financial crisis provided a good part of the motivation behind that undertaking.48 But the short-term financial relief of the government’s funds was limited as the expenditure on education started to drop only in 1885 (see Table 9.1)49 -- when Bruce's revisions had been enacted as the Revised Code for Schools in 1880. At least, the provisions of the Revised Code checked the rapid and hitherto almost uncontrolled multiplication of missionary grant-in-aid schools to a certain extent. One of the most important measures of the code was the introduction of higher average attendance requirements for A, B and C schools in order to receive a grant. Furthermore, schools that did not fulfill the requirements could now be removed from the grants list altogether.50 The Distance Rule of 1874 was confirmed and its three-mile clause substituted by a two-mile equivalent. These measures brought the expansion of grant-in-aid schools to a temporary halt between 1880 and 1886 (see Table 9.2), but would not lead to a substantial decrease of education expenditure. When expenditure did start to drop in the year 1885, it was not a direct consequence of the Revised Code for Schools implemented five years earlier. Rather, the government’s retreat from English education and the closing (or transfer) of government schools in municipalities caused the drop.

Moreover, the new Director of Public Instruction H.W. Green had reduced the grants assigned to English schools to the same rate payable to Anglo-vernacular or vernacular schools in the new Revised Code for Aided Schools in 1885.51

Table 9.1: Expenditure on Education and Total Expenditure, 1880-1900.

Year / ( I ) / (2) / (3) / (4) / (5)

1880 / 223,951 / 286,505 / 510,456 / 14,264,490 / 3.58

1881 / 230,522 / 273,779 / 504,301 / 13,533,259 / 3.73

1882 / 237,420 / 272,515 / 509,935 / 12,494,664 / 4.08

1883 / 235,356 / 255,875 / 491,23 I / 12,222,234 / 4.02

1884 / 237,153 / 263,356 / 500,509 / 12,318,218 / 4.06

1885 / 197,653 / 237,338 / 434,991 / 12,611 ,207 / 3.15

1886 / 198,546 / 248, 770 / 447,316 / 13,013,067 / 3.44

1887 / 205,751 / 255,022 / 460,113 / 13,313,039 / 3.46

1888 / 208,649/ 259,696 / 468,345 / 14,630,121 / 3.2

1889 / 213,989 / 272,521 / 486,510 / 14,906,281 / 3.26

1890 / 214,I 90 / 271,127 / 485,317 / 15,316 ,224 / 3.17

1891 / 215,023 / 302,628 / 517,651 / 16,435,079 / 3.15

1892 / na /na / 546,295 / 17,762,466 / 3.08

1893 / na / na / 600,837 / 18,276,108 / 3.29

1894 / na / na / 597,388 / 20,342,899 / 2.94

1895 / na / na / 636,270 / 20,899,714 / 3.04

1896 / na / na / 668,274 / 21,237,860 / 3.15

1897 / na / na / 716,767 / 21 ,634,378 / 3.31

1898 / na / na / 738,122 / 22,843,852 / 3.23

1899 / na / na / 778,134 / 24,950,940 / 3.12

1900 / na / na / 820,134 / 25,321,988 / 3.24

Source: Ceylon Statistical Blue Books, 1880- 1900.

(1) Expenditure on the Department of Public Instruction (Rs)

(2) Expenditure on Educational Services (Rs)

(3) Total Expenditure on Education (Rs)

(4) Total Expenditure of the Colony (Rs)

(5) % of (3) of (4)

During the 1870s the competition for government grants between the different Christian denominations had not only led to the uncontrolled multiplication of missionary schools in Ceylon, the establishment of numerous schools with unqualified staff and insufficient equipment had also been a side-effect of this rush into education. If such schools were located in the right places and run by the right management, they received a grant even if they could not live up to the general educational standards. The main reason for the establishment of ill-equipped schools was the fact that the government grants of the prosperous 1870s had often sufficed to cover the total costs of a school.52 The management had to contribute only marginal sums out of its own pocket.

Table 9.2: Government, Grant-in-Aid and Unaided Schools 1880-1900

-- / Government Schools / Grant-in-Aid Schools / Unaided Schools*

Year / Schools / Pupils / Schools / Pupils / Schools* / Pupils*

1880 / 369 / 21,29 4 / 833 / 59,820 / 585 / 7,236

1881 / 398 / 23,626 / 839 / 61,131 / 645/ 8,874

1882 / 421 / 26,597 / 832 / 62,842 / na / na

1883 / 437 / 27,656 / 836 / 61,374 / 652 / 12,291

1884 / 431 / 27,677 / 814/ 59,776 / 560 / 13,265

1885 / 417 / 26,624/ 819 / 57,320 / 2,134 / 20,062

1886 / 425 / 29,653/ 849 / 57,955 / 2, 126 / 22,956

1887 / 440 / 32,565 / 899 / 62,995 / 2,292 / 24,994

1888 / 438 / 35,948 / 919 / 66,400 / 2,427 / 28,823

1889 / 440 / 39,026 / 938/ 69,483/ 2,590 / 29,785

1890 / 436 / 40,290 / 984 / 73 ,698 / 2,617 / 32,464

1891 / 436 / 41 ,746 / 971 / 74,855 / 2,645 / 37,242

1892 / 453 / 42,190 / 1,024 / 82,637 / 2,395 / 33,631

1893 / 456 / 41 ,680 / 1,005 / 81,598 / 2,415 / 33,969

1894 / 468 / 44,366 / 1,042 / 86,968 / 2,408 / 32,576

1895 / 477 / 44,252 / 1,096 / 90,229 / 2,242 / 35,353

1896 / 474 / 44,538 / 1,130 / 94,400 / 2,268 36,720

1897 / 474 / 45,113 / 1,172 / 102,485 / 2,331 / /36,908

1898 / 479 / 46,279 / 1,220 / 103,951 / 2,330 / 34,805

1899 / 489 / 47,482 / 1,263 / 111,145 / 1,887 / 34,841

1900 / 500 / 48,642 / 1,328 / 120,751 / 2,089 / 38,881

Source: Administration Reports 1880-1900 .

• Punsala schools included from 1885 onwards

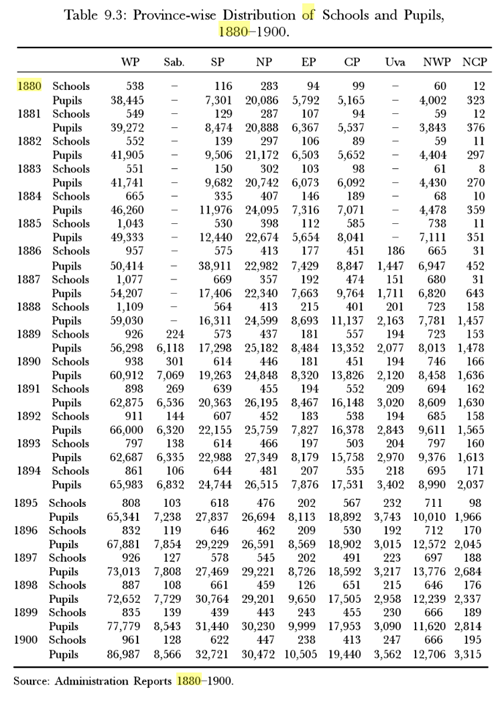

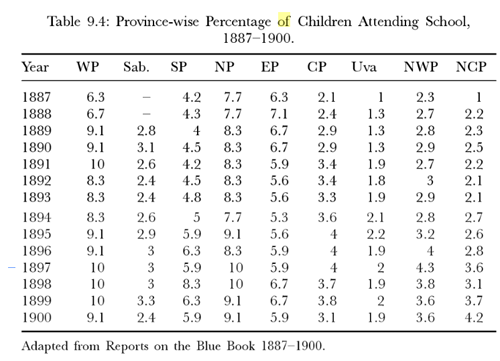

It was the main goal of the Revised Code for Schools of 1880 to prevent the further multiplication of such inefficient schools. Judging from the statistics the code was at least partially successful in that regard. Another problem of the educational system in Ceylon lay in the uneven distribution of educational facilities on the island. Most government and missionary schools were concentrated in the Western and Northern Province.53 The spread of education in the poverty-stricken North-Central province was totally neglected until 1887. In that year, only 31 schools with 643 pupils existed in the whole province, while the Western Province had 1,077 schools and 54,207 pupils (these figures include government, grant-in-aid and unaided schools).54 Table 9.3 and Table 9.4 show the province-wise distribution of schools and pupils and the percentage of all children attending school in each province.

Table 9.3: Province-wise Distribution of Schools and Pupils, 1880-1900

Table 9.4: Province-wise Percentage of Children Attending School, 1887-1900

The implementation of the Distance Rule and its confirmation in 1880 do not seem to have contributed substantially to a more even spread of education over the whole island. Only in 1888, the number of schools in the NCP started to increase, but the number of pupils per schools averaged only ten to fifteen between 1888 and 1900.55 Charles Bruce believed that only additional government resources and an annual education expenditure of 5% of the total government revenue could remedy the uneven distribution of educational facilities. Unsurprisingly, his proposals were not implemented.56

The missionary monopoly on government grants slowly started to break up in the 1890s, but the missionary societies still enjoyed a greatly privileged position within the grant-in-aid system. In 1900, Protestant missionary societies controlled 58.8% of all grant-aided schools (attended by 52.4% of all pupils of grant-in-aid schools). The Roman Catholics managed 25.3% of the aided schools with 27.8% of the pupils. By that time, however, the efforts of the indigenous communities had at least borne some fruits. The Buddhists now ran 10.7% of the aided schools and taught 15% of the pupils. Hindu schools accounted for 4.9% of all grant-in-aid schools with 5.9% of the pupils. The Muslims had been only marginally successful. In 1900 they managed 4 (0.3%) grant-aided schools with 199 (0.3%) pupils.57

The struggle of the Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims for adequate representation in the field of education will be discussed in detail in the chapter on "The Religious Revivals." But it must be noted here that the partial success of these communities' ambitions by the year 1900 is even more noteworthy if we recapitulate the provisions of the Distance Rules. In 1880, the so-called two-mile rule had been introduced to substitute the three-mile rule of 1874. Jayasuriya quotes the provisions of the two-mile rule:

As a general rule, no application will be entertained for aid to a boys' school when there already exists a flourishing boys' school of the same class within two miles of the proposed site, without some intervening obstacle, unless the average daily attendance for six months prior to the date of the application exceeds 60. An Anglo-vernacular school will be considered as of the same class as a vernacular school.58

The narrowing of the three-mile radius to only two miles did not have much practical effect, because the network of existing government or grant-in-aid schools covered the more interesting locations in the towns tightly enough to prevent the establishment of new schools under the provisions of 1880 as well. But the introduction of the average attendance requirements for six months prior to the application made an exception to the rule -- as provided for under exceptional circumstances in the circular of 1874 -- even harder. The two-mile rule of 1880, therefore, further hampered the progress of indigenous schools. But the most serious setback to the ambitions of the Buddhists and Hindus came in 1891 with the amendment of the two-mile rule. The required average attendance of 60 pupils for boys' schools and 40 for girls' schools was extended from six to twelve months prior to the application. Furthermore, the so-called quarter-mile rule was introduced, and no grant-aided school could be established within a quarter of a mile of another school of the same class -- under no circumstances whatsoever. The amendment was a serious blow to the Buddhists and Hindus for two reasons: first, in more densely populated areas the native religious groups had frequently succeeded in maintaining the required average attendance for the registration of a grant. This became more difficult now with the extension of the period to twelve months. And if the new school was situated within a quarter of a mile of another school, the registration for a grant was impossible now. In smaller towns and villages with already established schools, this rule often prevented the allocation of new grants completely.59 These provisions were detrimental enough to Buddhist and Hindu ambitions in the field, but the real harm was done by the retrospective application of the amended rule. Already existing and registered schools that fell under the provisions of the quarter-mile rule lost their grant and many had to be closed down.60 Under these adverse circumstances the number of grant-aided Buddhist and Hindu schools in the year 1900 (as shown above) appears to be even more noteworthy. The existence of these schools clearly indicates the momentum that the indigenous religious revivals had gained by the late 1880s and 1890s.