Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

Fort William College [East India College Calcutta]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/15/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

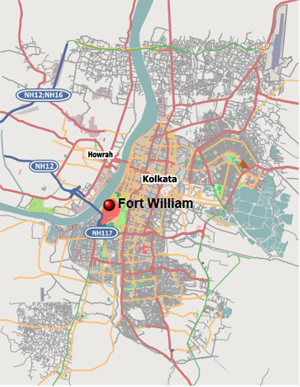

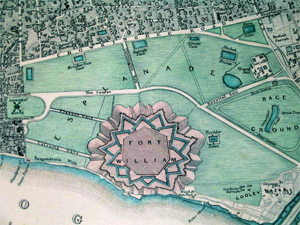

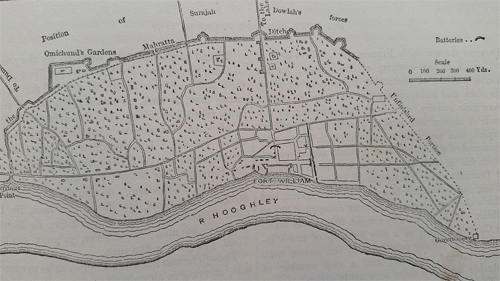

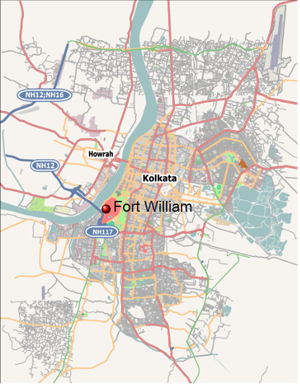

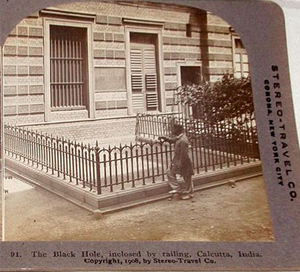

Fort William, Calcutta

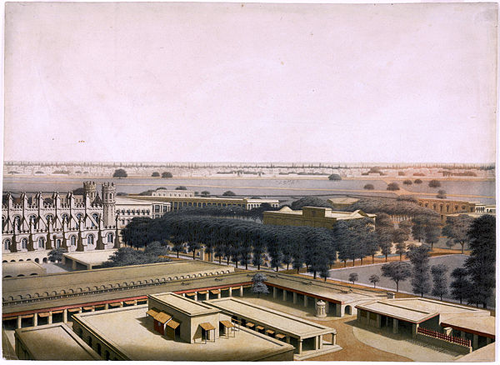

Fort William College, Calcutta (Kolkata). puronokolkata.com

Fort William College, Calcutta (variant College of Fort William) (1800 - 1854) was an academy of Oriental studies and a centre of learning. Founded on 10 July 1800, within the Fort William complex in Calcutta by Lord Wellesley, then Governor-General of British India. The statute of foundation was passed on 4 May 1800, to commemorate the first anniversary of the victory over Tipu Sultan at Seringapatam.[1] Thousands of books were translated from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Hindi, and Urdu into English at this institution. This college also promoted the printing and publishing of Urdu books.

Languages

Fort William College aimed at training British officials in Indian languages and, in the process, fostered the development of languages such as Bengali and Urdu.[4] The period is of historical importance. In 1815, Ram Mohan Roy settled in Calcutta. It is considered by many historians to be the starting point of the Bengali Renaissance.[5]:212 Establishment of The Calcutta Madrassa in 1781, the Asiatic Society in 1784 and the Fort William College in 1800, completed the first phase of Kolkata’s emergence as an intellectual centre.[2]

Teaching of Asian languages dominated: Arabic, Urdu, Persian, Sanskrit, Bengali. Later, Marathi and even Chinese were added.[6] Each department of the college was staffed by notable scholars. The Persian department was headed by Neil B. Edmonstone, Persian translator to the East India Company's government since 1794. His assistant teacher was John H. Harington, a judge of Sadar Diwani Adalat and Francis Gladwin, a soldier diplomat. For Arabic studies, there was Lt. John Baillie, a noted Arabist. The Urdu department was entrusted to John Borthwick Gilchrist, an Indologist of great repute. Henry Thomas Colebrooke, the famous orientalist, was head of the Sanskrit department. William Carey, a non-civilian missionary and a specialist in many Indian languages, was selected to head the department of vernacular languages.[7] While notable scholars were identified and appointed for different languages, there was no suitable person in Calcutta who could be appointed to teach Bengali. In those days, the Brahmin scholars learnt only Sanskrit, considered to be the language of the gods, and they did not study Bengali. The authorities decided to appoint Carey, who was with the Baptist Mission in Serampore. He, in turn, appointed Mrityunjoy Vidyalankar as head pandit, Ramnath Bachaspati as second pandit and Ramram Basu as one of the assistant pandits.[8]

Along with teaching, translations were organized. The college employed more than one hundred local linguists.[6] There were no textbooks available in Bengali. On 23 April 1789, the Calcutta Gazette published the humble request of several natives of Bengal for a Bengali grammar and dictionary.[8]

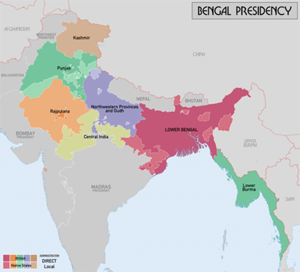

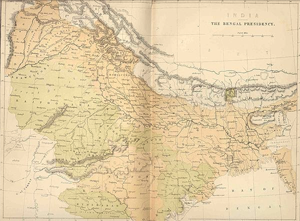

Location

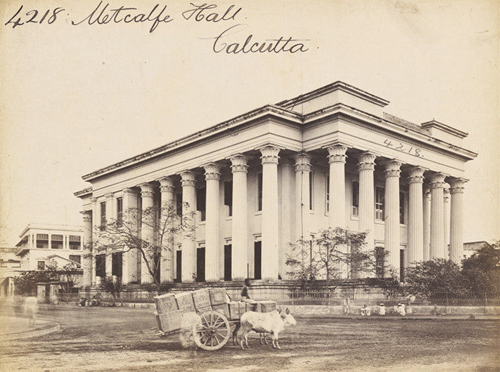

Fort William College, The Exchange, Calcutta, c1800 Jan, by অযান্ত্রিক

The college was located at the corner of Council House Street and the parade ground, (now named Maidan). After the college closed the building had a series of occupancies. First it was The Exchange of Messrs. Mackenzie Lyall & Co., then offices of the Bengal Nagpur Railway,[9]:271 and lastly the Raj Bhavan ('Government House').[9]:544

Library

The College library of Fort William was an important centre of learning and housed a magnificent collection of old manuscripts and many valuable historical books from across South Asia. Multiple MS copies were printed.[6] [10] When the college was dissolved in 1854, the books of the collection listed for preservation were transferred to the newly formed Calcutta Public Library, now the National Library.[6]

Hurdles

The court of directors of the British East India Company were never in favour of a training college in Calcutta, and for that reason there was always a lack of funds for running the college. Subsequently, a separate college for the purpose, the East India Company College at Haileybury (England), was established in 1807. However, Fort William College continued to be a centre of learning languages.[6][7]

With the British settling down in the seat of power, their requirements changed. Lord William Bentinck announced his educational policy of public instruction in English in 1835, mostly to cater to the growing needs of administration and commerce.[5]:236 He clipped the wings of Fort William College, and the Dalhousie administration formally dissolved the institution in 1854.[7]

Eminent scholars

Fort William College was served by a number of eminent scholars. They contributed enormously towards development of Indian languages and literature. Some of them are noted below:

• William Carey (1761–1834) was with Fort William College from 1801 to 1831. During this period he published a Bengali grammar and dictionary, numerous textbooks, the Bible, grammar and dictionary in other Indian languages.[11]:112

• Matthew Lumsden (1777–1835)

• John Borthwick Gilchrist (June 1759 – 1841)

• Mrityunjay Vidyalankar (c. 1762 – 1819) was First Pandit at Fort William College. He wrote a number of textbooks and is considered the first 'conscious artist' of Bengali prose.[12] Although a Sanskrit scholar he started writing Bengali as per the needs of Fort William College. He published Batris Singhasan (1802), Hitopodesh (1808) and Rajabali (1808). The last named book was the first published history of India. Mrityunjoy did not know English so the contents were possibly provided by other scholars of Fort William College.[8]

• Tarini Charan Mitra (1772–1837), a scholar in English, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic and Persian, was with the Hindustani department of Fort William College. He had translated many stories into Bengali.[11]:196

• Lallu Lal (also spelt as Lalloolal or Lallo Lal), the father of Hindi Khariboli prose, was instructor in Hindustani at Fort William College. He printed and published in 1815 the first book in the old Hindi literary language Braj Bhasha, Tulsidas’s Vinaypatrika.[4]

• Ramram Basu (1757–1813) was with the Fort William College. He assisted William Carey, Joshua Marshman and William Ward in the publication of the first Bengali translation of the Bible.[4]

• Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820–1891) was head pandit at Fort William College from 1841 to 1846. He concentrated on English and Hindi while serving in the college.[11]:64 After discharging his duties as academician, and engagements as a reformer he had little time for creative writing. Yet through the textbooks he produced, the pamphlets he wrote and retelling of Kalidasa’s Shakuntala and Shakespeare’s A Comedy of Errors he set the norm of standard Bengali prose.[2]

• Madan Mohan Tarkalankar (1817–1858) taught at Fort William College. He was one of the pioneers of textbook writing.[11]:391

References

1. Danvers, FC; M. Monier-Williams; et al. (1894). Memorials of Old Haileybury College. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company. p. 238.

2. Majumdar, Swapan, Literature and Literary Life in Old Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, pp. 107–9, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

3. Reader in Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University and Director of the Indian Cultural Centre at Suva, Fiji. Ref: Calcutta, the Living City, Vol. I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, p. vii, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

4. Sarkar, Nikhil, Printing and the Spirit of Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol. I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, pp. 130–2, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

5. Sengupta, Nitish, 2001–02, History of the Bengali-speaking People, UBS Publishers’ Distributors Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

6. Diehl, Katharine Smith. "College of Fort William". College of Fort William. Katharine Smith Diehl Seguin, Texas. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

7. Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Fort William College". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

8. Mukhopadhyay, Prabhatkumar, Rammohun O Tatkalin Samaj O Sahitya, 1965, pp. 47–51, Viswa Bharati Granthan Bibhag (in Bengali).

9. Cotton, H.E.A., Calcutta Old and New, 1909/1980, General Printers and Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

10. Pritchett, Frances. "Selected publications of Fort William College" (PDF). First Editions recommended for preservation. Columbia University. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

11. Sengupta, Subodh Chandra and Bose, Anjali (editors), 1976/1998, Sansad Bangali Charitabhidhan(Biographical dictionary) Vol I, ISBN 81-85626-65-0 (in Bengali).

12. Acharya, Poromesh, Education in Old Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, pp. 108–9, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

Further reading

• Bowen, John (October 1955). "The East India Company's Education of its Own Servants". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. New Series. London: The Royal Asiatic Society. 87: 105–123. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00114029.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/15/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Appendix II: The College of Fort William in Its Connexion with the East India College, Haileybury.

On the 18th of August, 1800, the Marquis Wellesley, Governor-General of India, wrote a minute in Council containing his reasons for establishing a College at Fort William, Calcutta.

It was a long document which, when printed, occupied nearly 43 pages 4to. I subjoin a brief summary: --The age at which writers usually arrive in India [N.B., this was written in 1800] is from sixteen to eighteen. Some of them have been educated with a view to the Indian Civil Service, but on utterly erroneous principles; their education being confined to commercial knowledge and in no degree extended to liberal studies. On arrival in India they are either stationed in the interior, where they ought to be conversant with the languages, laws, and customs of the natives, or they are employed in Government offices where they are chiefly occupied in transcribing papers. Once landed in India their studies, morals, manners, expenses and conduct are no longer subject to any regulation, restraint, or guidance. Hence they often acquire habits destructive to their health and fortunes.

Under these circumstances the General has determined to found a College at Fort William in Bengal for the instruction of the junior Civil Servants in such branches of literature, science, and knowledge as may be deemed necessary to qualify them for the discharge of their duties; and, considering that such a College would be a becoming public monument to commemorate the Conquest of Mysore, he has dated the law for the foundation of the College on the 4th of May, 1800, the first anniversary of the reduction of Seringapatam.

A suitable building is to be erected at Garden Reach. There will be a Provost, Vice-Provost, and a complete staff of Professors both of European and Oriental subjects.1 [1. A list of these was printed. I select the following: -- Provost, Rev. David Brown; Vice-Provost, Rev. C. Buchanan (both of these were Chaplains of the H.E.I.C.S.); Sanskrit and Hindu Law, H.T. Colebrooke; British Law, Sir George Barlow, Bart.; Greek and Latin Classics, Rev. C. Buchanan; Persian, Francis Gladwin; Assistant in Persian and Arabic, Mathew Lumsden; second Assistant in Persian, Capt. Charles Stewart; Sanskrit and Bengali, Rev. William Carey; Hindustani, John Gilchrist.] Statutes are to be drawn up, and all Indian civilians on first arriving in India, even those destined for Bombay and Madras are to be educated at this College, which will be called the College of Fort William.

The statutes were promulgated by the first Provost (the Rev. David Brown), on April 10, 1801, and when printed occupied 12 pages 4to. The students were then located in provisional buildings, and the first Disputation in Oriental languages was held on the 6th of February, 1802; a speech being delivered on the occasion by Sir George Barlow, the acting Visitor. All this was done without the knowledge of the Court of Directors in London, who, when they heard of the foundation of the College, passed a resolution against it, on the ground of the enormous and indefinite expenditure which it might involve. They complimented the Marquis on his able minute, and acknowledged the necessity for obtaining a higher class of civil servants by raising the standard of their education and giving them an improved special training, but they only expressed their approbation of part of his plan. In fact a compromise was arranged (see note to line 6 of page 27 of this volume), and it was decided that although the proposed collegiate Building at Garden Reach was not to be erected, an Institution to be called “The East-India College” should be founded in Hertfordshire, which was to give a good general education, combined with instruction in the rudiments of the Oriental languages, while Lord Wellesley’s Institution was to be allowed to continue at Calcutta in a less comprehensive form under the name of Fort William College, with a local habitation in “Writers’ Buildings,” the name given to a long house with good verandahs looking south at the north end of Tank Square (now Dalhousie Square).

It was thus brought about that Fort William College became a kind of continuation of Haileybury, and that its work was restricted to the imparting of fuller instruction in Oriental subjects, the groundwork of which had been laid at Haileybury. And no doubt it was originally intended that all junior civilians who had passed through the Haileybury course should repair to the College in Calcutta for such instruction. Moreover, the process of sifting, which began at Haileybury, was continued at the Forst William Institution. At any rate, it occasionally happened that the worst of those “bad bargains,” which Haileybury, in its too great leniency, had spared, were eliminated from the service at Calcutta.

Yet, according to Mr. Malthus, the discipline at Fort William College was for some time in a most unsatisfactory state. He mentions that far too large a number of young civilians, whose ages ranged from 16 to 19, were collected at Calcutta between 1801 and 1808 (Haileybury being then barely founded, or at least not in actual working order), and that much dissipation and irregularity existed among them (Pamphlet, pp. 55-56).

Unquestionably the establishment of Haileybury had a beneficial effect in abridging the period of residence at Calcutta, as the following extract from Mr. Malthus’ pamphlet proves: --In 1811 twenty students left Fort William College qualified for official situations. Of the twelve who had been previously at Haileybury, six left after six month’s residence, two after eight months, one after nine months, one after two years, two after three years. Of the eight who had not been at Haileybury three left after two and a quarter years, one after three years, one after three and a quarter years, two after four years, one after four and a half years.

Still, the co-existence of Haileybury in connexion with Fort William College does not seem to have caused much improvement in the state of the discipline at the latter college; for at p. 38 of Mr. Malthus’ pamphlet we read: --In the last public examination [N.B., this was written in 1817] at the College in India, of which the account has arrived, five students were expelled. Notwithstanding the opportunities afford to them during a protracted stay at Calcutta, they had not acquired such a knowledge of two Oriental languages as would enable them to pass the examination necessary to qualify them for an official situation.

It appears, then, from the above extracts that, after the founding of Haileybury, the period of residence at Fort William College was sometimes completed by good men in six months. On the other hand, in the case of inferior men, it was sometimes protracted for three or four years, or even more. It appears, too, that for many years those who were transferred from Haileybury to Fort William lived a collegiate life there somewhat similar to that at Haileybury; that is to say, they had rooms assigned to them in “Writers’ Buildings,” and were subject to some sort of collegiate discipline. Moreover, it is clear that, for three or four years, even Bombay and Madras civilians were required to present themselves at Calcutta and go through their period of Indian probation at Fort William.1 [1. Mr. W.S. Seton-Karr has lent me a curious and scarce volume entitled “Roebuck’s Annals of the College of Fort William.” There I find reports of the results of all the examinations from 1801 to 1818, and it may be proved from these reports that civilians destined for Bombay and Madras gained prizes at Fort William in the years 1801-1804, and notably among them was a connexion of my own, Mr. John Romer, who was for some time a Judge in the Bombay Presidency.] As to Bengal civilians their residence there went on, I believe, till about the year 1835. So far as I have been able to ascertain, it was not till after that year that they were allowed to reside with their friends or in “chummeries,” or in lodgings anywhere in the town.2 [2. Mr. Seton-Karr tells me then in 1842 he and Mr. R.N. Cust and Mr. Montresor took a good three-storied house in Middleton Row, Calcutta, and there “chummed” together during their period of probation.] Even after that date, however, they had to go to “Writers’ Buildings” (where there was a good Library and Examination Room) for their monthly and final examinations.3 [3. Mr. Seton-Karr informs me, that in 1842 the two examiners (Colonel Ouseley, and Capt. Marshall) had offices in “Writers’ Buildings,” and that monthly examinations were held there, but that a considerable portion of the building was then let out as merchants’ offices.]

The annual Fort William “Disputations” (corresponding to the Haileybury “Visitations”), which took place in early years, were generally held at Government House, the Governor-General being the “Visitor,” but I find that in one year (1802) these “Disputations” – accompanied as they always were by a public distribution of prizes, and a speech from the Governor-General – took place in the Examination-room of the College Buildings.

It was not till January 24, 1854, that the College of Fort William was abolished. That year saw both the first introduction of the Indian Civil Service competitive system into England, and at the same time a change in the method of dealing with Indian civilians on their first arrival in India. Nevertheless, even after that year, examinations continued to be held in India under Boards of Examiners appointed by the Government, but not under collegiate regulations or in any special building.

Monier Monier-Williams.

-- Memorials of Old Haileybury College, by Frederick Charles Danvers, Sir Monier Monier-Williams, Sir Steuart Colvin Bayley, Percy Wigram, Brand Sapte

But it would be unpardonable not to speak of the College at Calcutta, of which the original plan was doubtless the most magnificent attempt ever made for the promotion of learning in the East. I am not conscious that I am biased either by personal feelings or literary prejudices, when I say that I consider that original plan as a wise and noble proposition, of which the adoption in its full extent would have had the happiest tendency to secure the good government of India, as well as to promote the interest of science. Even in its present mutilated state we have seen, at the last public exhibition, Sanscrit declamations by English youth; a circumstance so extraordinary*, [*It must be remembered that this Discourse was read in 1804. In the present year, 1818, this circumstance could no longer be called extraordinary. From the learned care of Mr. Hamilton, late Professor of Indian Languages at the East India College, a proficiency in Sanscrit is become not uncommon in an European Institution.] that, if it be followed by suitable advances, it will mark an epoch in the history of learning.

-- Transactions of The Literary Society of Bombay, With Engravings

The Asiatic Society was founded by civil servant Sir William Jones on 15 January 1784 in a meeting presided over by Sir William Jones, Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William at the Fort William in Calcutta, then capital of the British Raj, to enhance and further the cause of Oriental research. At the time of its foundation, this Society was named as "Asiatick Society". In 1825, the society dropped the antique k without any formal resolution and the Society was renamed as "The Asiatic Society". In 1832 the name was changed to "The Asiatic Society of Bengal" and again in 1936 it was renamed as "The Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal". Finally, on 1 July 1951, the name of the society was changed to its present one. The Society is housed in a building at Park Street in Kolkata (Calcutta). The Society moved into this building during 1808. In 1823, the Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta was formed and all the meetings of this society were held in the Asiatic Society.

-- The Asiatic Society [Asiatic Society of Bengal / Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal], by Wikipedia

Fort William, Calcutta

Fort William College, Calcutta (Kolkata). puronokolkata.com

Fort William College, Calcutta (variant College of Fort William) (1800 - 1854) was an academy of Oriental studies and a centre of learning. Founded on 10 July 1800, within the Fort William complex in Calcutta by Lord Wellesley, then Governor-General of British India. The statute of foundation was passed on 4 May 1800, to commemorate the first anniversary of the victory over Tipu Sultan at Seringapatam.[1] Thousands of books were translated from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Hindi, and Urdu into English at this institution. This college also promoted the printing and publishing of Urdu books.

Languages

The College of Fort William emerged as both a centre of research and a publication unit, a cradle of creativity as well as scholarship. Planned originally to train probationer British civilians in the languages and cultures of the subjugated country, the college rendered services tantamount to those of a university in promoting modern Indian literatures, Bengali in particular… Under the leadership of William Carey, the College could also claim credit for drawing together Sanskrit pandits and Perso-Arabic munshis to reshape Bengali prose… The variety of the College’s publication also deserve note. From colloquies and popular stories, chronicles and legends, to definitive editions of literary texts.[2]

-- Majumdar, Swapan[3]

Fort William College aimed at training British officials in Indian languages and, in the process, fostered the development of languages such as Bengali and Urdu.[4] The period is of historical importance. In 1815, Ram Mohan Roy settled in Calcutta. It is considered by many historians to be the starting point of the Bengali Renaissance.[5]:212 Establishment of The Calcutta Madrassa in 1781, the Asiatic Society in 1784 and the Fort William College in 1800, completed the first phase of Kolkata’s emergence as an intellectual centre.[2]

Teaching of Asian languages dominated: Arabic, Urdu, Persian, Sanskrit, Bengali. Later, Marathi and even Chinese were added.[6] Each department of the college was staffed by notable scholars. The Persian department was headed by Neil B. Edmonstone, Persian translator to the East India Company's government since 1794. His assistant teacher was John H. Harington, a judge of Sadar Diwani Adalat and Francis Gladwin, a soldier diplomat. For Arabic studies, there was Lt. John Baillie, a noted Arabist. The Urdu department was entrusted to John Borthwick Gilchrist, an Indologist of great repute. Henry Thomas Colebrooke, the famous orientalist, was head of the Sanskrit department. William Carey, a non-civilian missionary and a specialist in many Indian languages, was selected to head the department of vernacular languages.[7] While notable scholars were identified and appointed for different languages, there was no suitable person in Calcutta who could be appointed to teach Bengali. In those days, the Brahmin scholars learnt only Sanskrit, considered to be the language of the gods, and they did not study Bengali. The authorities decided to appoint Carey, who was with the Baptist Mission in Serampore. He, in turn, appointed Mrityunjoy Vidyalankar as head pandit, Ramnath Bachaspati as second pandit and Ramram Basu as one of the assistant pandits.[8]

Along with teaching, translations were organized. The college employed more than one hundred local linguists.[6] There were no textbooks available in Bengali. On 23 April 1789, the Calcutta Gazette published the humble request of several natives of Bengal for a Bengali grammar and dictionary.[8]

Location

Fort William College, The Exchange, Calcutta, c1800 Jan, by অযান্ত্রিক

The college was located at the corner of Council House Street and the parade ground, (now named Maidan). After the college closed the building had a series of occupancies. First it was The Exchange of Messrs. Mackenzie Lyall & Co., then offices of the Bengal Nagpur Railway,[9]:271 and lastly the Raj Bhavan ('Government House').[9]:544

Library

The College library of Fort William was an important centre of learning and housed a magnificent collection of old manuscripts and many valuable historical books from across South Asia. Multiple MS copies were printed.[6] [10] When the college was dissolved in 1854, the books of the collection listed for preservation were transferred to the newly formed Calcutta Public Library, now the National Library.[6]

Hurdles

The court of directors of the British East India Company were never in favour of a training college in Calcutta, and for that reason there was always a lack of funds for running the college. Subsequently, a separate college for the purpose, the East India Company College at Haileybury (England), was established in 1807. However, Fort William College continued to be a centre of learning languages.[6][7]

With the British settling down in the seat of power, their requirements changed. Lord William Bentinck announced his educational policy of public instruction in English in 1835, mostly to cater to the growing needs of administration and commerce.[5]:236 He clipped the wings of Fort William College, and the Dalhousie administration formally dissolved the institution in 1854.[7]

Eminent scholars

Fort William College was served by a number of eminent scholars. They contributed enormously towards development of Indian languages and literature. Some of them are noted below:

• William Carey (1761–1834) was with Fort William College from 1801 to 1831. During this period he published a Bengali grammar and dictionary, numerous textbooks, the Bible, grammar and dictionary in other Indian languages.[11]:112

• Matthew Lumsden (1777–1835)

• John Borthwick Gilchrist (June 1759 – 1841)

• Mrityunjay Vidyalankar (c. 1762 – 1819) was First Pandit at Fort William College. He wrote a number of textbooks and is considered the first 'conscious artist' of Bengali prose.[12] Although a Sanskrit scholar he started writing Bengali as per the needs of Fort William College. He published Batris Singhasan (1802), Hitopodesh (1808) and Rajabali (1808). The last named book was the first published history of India. Mrityunjoy did not know English so the contents were possibly provided by other scholars of Fort William College.[8]

• Tarini Charan Mitra (1772–1837), a scholar in English, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic and Persian, was with the Hindustani department of Fort William College. He had translated many stories into Bengali.[11]:196

• Lallu Lal (also spelt as Lalloolal or Lallo Lal), the father of Hindi Khariboli prose, was instructor in Hindustani at Fort William College. He printed and published in 1815 the first book in the old Hindi literary language Braj Bhasha, Tulsidas’s Vinaypatrika.[4]

• Ramram Basu (1757–1813) was with the Fort William College. He assisted William Carey, Joshua Marshman and William Ward in the publication of the first Bengali translation of the Bible.[4]

• Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820–1891) was head pandit at Fort William College from 1841 to 1846. He concentrated on English and Hindi while serving in the college.[11]:64 After discharging his duties as academician, and engagements as a reformer he had little time for creative writing. Yet through the textbooks he produced, the pamphlets he wrote and retelling of Kalidasa’s Shakuntala and Shakespeare’s A Comedy of Errors he set the norm of standard Bengali prose.[2]

• Madan Mohan Tarkalankar (1817–1858) taught at Fort William College. He was one of the pioneers of textbook writing.[11]:391

References

1. Danvers, FC; M. Monier-Williams; et al. (1894). Memorials of Old Haileybury College. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company. p. 238.

2. Majumdar, Swapan, Literature and Literary Life in Old Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, pp. 107–9, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

3. Reader in Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University and Director of the Indian Cultural Centre at Suva, Fiji. Ref: Calcutta, the Living City, Vol. I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, p. vii, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

4. Sarkar, Nikhil, Printing and the Spirit of Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol. I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, pp. 130–2, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

5. Sengupta, Nitish, 2001–02, History of the Bengali-speaking People, UBS Publishers’ Distributors Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

6. Diehl, Katharine Smith. "College of Fort William". College of Fort William. Katharine Smith Diehl Seguin, Texas. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

7. Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Fort William College". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

8. Mukhopadhyay, Prabhatkumar, Rammohun O Tatkalin Samaj O Sahitya, 1965, pp. 47–51, Viswa Bharati Granthan Bibhag (in Bengali).

9. Cotton, H.E.A., Calcutta Old and New, 1909/1980, General Printers and Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

10. Pritchett, Frances. "Selected publications of Fort William College" (PDF). First Editions recommended for preservation. Columbia University. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

11. Sengupta, Subodh Chandra and Bose, Anjali (editors), 1976/1998, Sansad Bangali Charitabhidhan(Biographical dictionary) Vol I, ISBN 81-85626-65-0 (in Bengali).

12. Acharya, Poromesh, Education in Old Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol I, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, pp. 108–9, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1.

Further reading

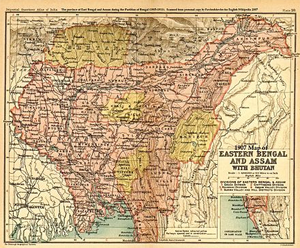

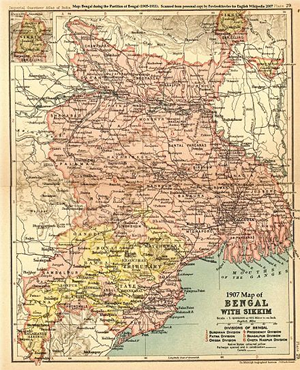

• Bowen, John (October 1955). "The East India Company's Education of its Own Servants". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. New Series. London: The Royal Asiatic Society. 87: 105–123. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00114029.