by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/30/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A resident, or in full resident minister, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of indirect rule.

A resident usually heads an administrative area called a residency.

Resident ministers

This full style occurred commonly as a diplomatic rank for the head of a mission ranking just below envoy, usually reflecting the relatively low status of the states of origin and/or residency, or else difficult relations.

On occasion, the resident minister's role could become extremely important, as when in 1806 the Bourbon king Ferdinand IV fled his Kingdom of Naples, and Lord William Bentinck, the British Resident, authored (1812) a new and relatively liberal constitution.

Residents could also be posted with shadowy governments. For instance, the British sent residents to the Mameluk Beys who ruled Baghdad province as an autonomous state (1704–1831) in the north of present-day Iraq, until the Ottoman sultans regained control over it (1831) and its Wali (governor).

Even after the Congress of Vienna restored the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in 1815, the British posted a "mere" resident to Florence.

As international relations developed, it became customary to give the highest title of diplomatic rank – ambassador – to the head of all permanent missions in any country, except as a temporary expression of down-graded relations or where representation was merely an interim arrangement.

Pseudo-colonial residents

Some official representatives of European colonial powers, while in theory diplomats, in practice exercised a degree of indirect rule. Some such residents were former military officers, rather than career diplomats, who resided in smaller self-governing protectorates and tributary states and acted as political advisors to the rulers. A trusted resident could even become the de facto prime minister to a native ruler. In other respects they acted as an ambassador of their own government, but at a lower level, since even large and rich native states were usually seen as inferior to Western nations. Instead of being a representative to a single ruler, a resident could be posted to more than one native state, or to a grouping of states which the European power decided for its convenience. This could create an artificial geographical unit, as in Residency X in some parts of the British Indian Empire.

Similar positions could carry alternative titles, such as political agent and resident commissioner.

In some cases, the intertwining of the European power with the traditional native establishment went so far that members of the native princely houses became residents, either in other states or even within their own state, provided that they were unlikely ever to succeed as ruler of the state.

A resident's real role varied enormously, depending upon the underlying relationship between the two parties and even upon the personalities of the Resident and the ruler(s). Some residents were little more than observers and diplomats, others were seen as the "face of the oppressor" and were treated with hostility, while some won enough trust from the ruler that they were able to exercise great influence. In French protectorates, such as those of Morocco and Tunisia, the resident or resident general was the effective ruler of the territory.

In 1887, when both Boers and gold prospectors of all nationalities were overrunning his country, the Swazi paramount chief Umbandine asked for a British resident, seeing this as a desirable and effective form of protection. His request was refused.

British and dominion residents

The residents of the governments of the United Kingdom and the dominions to a variety of protectorates include:

British and dominion residents

The residents of the governments of the United Kingdom and the dominions to a variety of protectorates include:

Residents in Africa

• In the Sultanate of Zanzibar, the second 'homeland' of the Omani dynasty, since 1913. From 1913 to 1961 the Residents were also the Sultan's vizier. There were Consuls and Consuls-general until 1963.

• In present-day Kenya, in the Sultanate of Witu, after the British took over the protectorate from the German Empire, which had itself posted a Resident.

• In British Cameroon (part of the former German Kamerun), since 1916, in 1949 restyled Special Resident (superior to the new two provinces) for Edward John Gibbons (b. 1906 – d. 1990), who stayed on in October 1954 as first Commissioner when it became an autonomous part of Nigeria.

• in Southern Africa:

o when the military party sent from Cape Colony to occupy Port Natal on behalf of Great Britain was recalled in 1839, a British Resident was appointed among the Fingo and other tribes in Kaffraria until the definite establishment of British rule in Natal and its 1845 organization as an administrative entity, when the incumbent Shepstone was made Agent for the native tribes.

o In kwaZulu, which since 1843 was under a British protectorate, after it became the Zulu "Native" Reserve or Zululand Province on 1 September 1879: two British Residents (William Douglas Wheelwright, 8 September 1879 to January 1880, then Sir Melmoth Osborn until 22 December 1882). Thereafter there were Resident Commissioners until Zululand was incorporated into the crown colony of Natal as British Zululand on 1 December 1897.

o in 1845 the resident 'north of the Orange river' chose his residency at Bloemfontein, which became the capital of the Orange River Sovereignty in 1848. In 1854 the British abandoned the Sovereignty, and the independent Boer republic of the Orange Free State was established

o in the Boer republic of Transvaal at Pretoria

o with the Matabele chief at Bulawayo

• in Ghana, with the rulers of the Asanteman Confederation (established in 1701), since it became in 1896 a British protectorate; on 23 June 1900 the Confederation was dissolved by UK protectorate authority, on 26 September 1901 turned into Ashanti Colony, so since 1902 his place was taken by a Chief Commissioner at Kumasi

• in various parts of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate, Southern Nigeria Protectorate and after their joining Nigeria protectorate, notably in Edo state at Benin City (first to the British-installed ruling council of chiefs, later to the restored Oba), with the Emir of and in Bauchi, to the jointly ruling bale and balogun of Ibadan (a vassal state in Yorubaland), with the Emir of Illorin, with the Emir of and in Muri (Nigeria), with the Emir of Nupe

Residents in Asia

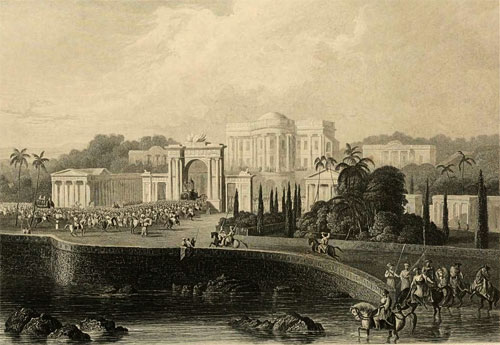

The British Residency at Hyderabad

British residents were posted in various princely states — in major states or groups of states—in the days of British India.[1] Often they were appointed to a single state, as with the Resident in Lucknow, the capital of Oudh; to the Maharaja Gaekwar of Baroda; to the Maharaja Sindhya of Gwalior; to the Nizam al-Mulk of Hyderabad; to the Maharaja Rana of Jhalawar; to the restored Maharaja of Mysore, after the fall of Tipu Sultan; to the Maharaja Sena Sahib Subah of the Mahratta state of Nagpur; to the (Maha)Raja of Manipur; to the (Maha)Raja of Travancore; to the Maharana of Mewar in Udaipur. Even when Lord Lake had broken the Mahratta power in 1803, and the Mughal emperor was taken under the protection of the East India Company, the districts of Delhi and Hissar were assigned for the maintenance of the royal family, and were administered by a British Resident, until in 1832 the whole area was annexed to British Residents were also posted in major states considered to be connected with India, neighbouring or on the sea route to it, notably:

• in Aden[1] (while subordinated to the Bombay Presidency), the only part of the present-day Yemen made a colony in full British possession. The last of three British Political Agents since 1939 stayed on as first Resident since 1859, the last again staying on in 1932 as first Chief Commissioner; he was the only diplomatic representative to the various Arabian rulers who over time accepted British protectorate, but since the 1935 legal separation from British India was followed in 1937 by a reorganisation into an Eastern and a Western Aden Protectorate (based at Mukallah and Lahej; together covering all Yemen), the British Representatives in each were styled British Political officers

• in Afghanistan, a kingdom entitled to a gun salute of 21 guns (the highest rank among princely states, not then among Sovereign monarchs): the first British Residents were Sir Alexander Burnes (1837 – 2 November 1841); William Hay McNaghten (7 August 1839 – 23 December 1841); Eldred Pottinger (December 1841 – 6 January 1842). After that, four native Vakils acted on behalf of the British government: Nawab Foujdar Khan (1856 – April 1859), Ghulam Husain Khan Allizai (April 1859 – 1865), Bukhiar Khan (February 1864 – January 1868, acting), Attah Muhammad Khan Khagwani (January 1868 – 1878); then there were two more British Residents Louis Napoleon Cavagnari (24 July 1879 – 3 September 1879), Henry Lepel-Griffin (1880); next came two Military Commanders (8 October 1879 – 11 August 1880) and until 1919 ten native British Agents, one of whom served two non-consecutive terms.

• Capt. Hiram Cox (died 1799)[2] was the first British Resident to the King of independent Burma (October 1796 – July 1797), and there were more discontinuous posting to that court, in the 19th century, never satisfactory to either party; after the British conquest of Burma there were two separate British Residents in a border zone of that country: in the Northern Shan States and in the Southern Shan States (each several tribal states, usually ruled by a Saopha=Sawbwa) in 1945–1948 (each group had been under a Superintendent from 1887/88 till 1922, then both jointly under a Resident Commissioner till the 1942 Japanese occupation)

• after five military governors since the East India Company started chasing the Dutch out of Ceylon in August 1795 and occupying the island (completed on 16 February 1796), their only Resident there was Robert Andrews, 12 February 1796 – 12 October 1798, who was subordinate to the presidency of Madras (see British India), afterwards the HEIC appointed Governors as it was made a separate colony

• to the Sultan of the Maldives archipelago since he formally accepted British protection on 16 December 1887 (informally since 1796, after the British took over Ceylon from the Dutch), but in fact this office was filled ex officio by the colonial Governors of until 4 February 1948, abolished on 26 July 1965

• in Nepal[1] since 1802, accredited to the Hindu Kings (title Maharajadhiraja), since 15 March 1816 exercising a de facto protectorate—the last staying on 1920 as Envoy till the 1923 emancipation

• with the Imam/Sultan of Oman, 1800–1804, 1805–1810 and 1840 (so twice interrupted by vacancy), then located with the African branch of the dynasty on the island of Unguja, since 1862 his role was handed over to a Political Agent

And elsewhere:

• in Transjordan (present Jordan) April 1921 – 17 June 1946 four incumbents accredited to the Hashemite Emir/King

Even in overseas territories occupied ('preventively' or conquered) to keep the French out of strategic trade and waters, residencies could be established, e.g. at Laye on Sumatra, an island returned to the Dutch East Indies

Residents in (British) European protectorates

Since on 5 November 1815 the United States of the Ionian Islands became a federal republic of seven islands (Corfu, Cephalonia, Zante, Santa Maura, Ithaca, Cerigo and Paxos), as a protectorate (nominally of the allied Powers; de facto UK protectorate; the highest office was the always-British Lord High Commissioner), until its 1 June 1864 incorporation into independent Greece, there were British residents, each posted with a local Prefect, on seven individual islands, notably: Cephalonia (Kephalonia), Cerigo (Kythira), Ithaca, Paxos, Santa Maura (Leucada/Lefkada) and Zante (Zakynthos)

Residents on (British and dominion) ocean island states

• in the early colonial settlement phase on New Zealand (where the Polynesian Māori declared independence on 28 October 1835 as the Confederation of the United Tribes, under a British protectorate), from 10 May 1833 James Busby (b. 1801 – d. 1871; from 1834–1836 jointly with Thomas McDonnell as co-resident) till 28 January 1840, then two lieutenant governors (as part of New South Wales, in Australia) and many governors since 3 January 1841

• at Rarotonga since the 1888 establishment of the British protectorate over the Cook Islands; the third and last incumbent stayed on as first Resident Commissioner since 1901, at the incorporation in the British Western Pacific Territories (under a single High Commissioner, till its 1976 dissolution, in Suva or Honoria), until the abolition of the post at the 1965 self-government grant as territory in free association with New Zealand, having its own cabinet (still under the British Crown, which after the 1976 appoints a special King's/Queen's Representative, as well as a High Commissioner).

Residents in protectorates of decolonised Commonwealth states

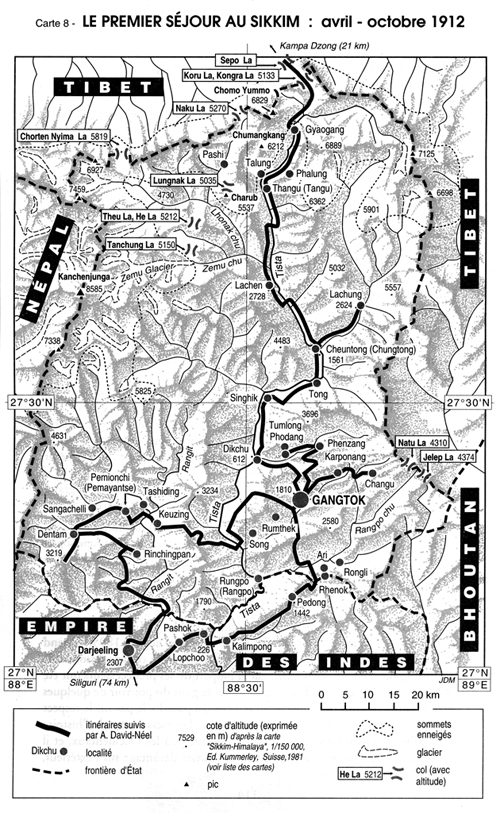

• Sikkim, where the Maharaja had been under a British protectorate (1861 – 15 August 1947; the crown representative was styled Political Agent), became immediately afterwards a protectorate of newly independent India (formally from 5 December 1950; in the meantime the Indian representative was again styled Political Agent, the first incumbent actually being the former British Political Agent—India was a dominion, still under the British crown, till 26 January 1950) until 16 May 1975, it was annexed as a constituent state of India.

Dutch colonial residents

In the Dutch East Indies, Dutch residents and lower ranks such as assistant residents were posted alongside a number of the many native princes in present Indonesia, compare Regentschap.

For example, on Sumatra, there were Dutch residents at Palembang, at Medan in Deli sultanate; another was posted with the Sultan of and on Ternate, and one in Bali.

French colonial residents

France also maintained residents, the French word being résident.

However the 'Jacobin' tradition of strict state authority didn't agree well with indirect rule, so often direct rule was preferred.

Many were part of a white colonial hierarchy, rather than truly posted with a native ruler or chieftain.

Style résident

• A single post of resident was also created in Côte d'Ivoire, i.e. Ivory Coast (from 1881 subordinated to the Superior Commandant of Gabon and the Gulf of Guinea Settlements; from 1886 subordinated to the Lieutenant Governors of Guinea), where in 1842 France had declared protectorates over the Kingdoms of Nzima and Sanwi (posts at Assinié 1843–1870, and Grand Bassam, Fort Dabou 1853–1872, part of the Colony of Gorée and Dependencies in Senegal]):

o 1871–1885 Arthur Verdier (to 1878 Warden of the French Flag) (b. 1835 – d. 1898)

o 1885–1886 Charles Bour -Commandant-particular

o 1886 – 9 March 1890 Marcel Treich Leplène (b. 1860 – d. 1890)

o 9 March 1890 – 14 June 1890 Jean Joseph Étienne Octave Péan (acting)

o 14 June 1890 – 1892 Jean Auguste Henri Desailles

o 1892 Éloi Bricard (acting)

o 1892 – 12 November 1892 Julien Voisin (acting)

o 12 November 1892 – 10 March 1893 Paul Alphonse Frédéric Heckman; thereafter it had its own Governors

• On the Comoros, in the Indian Ocean, several Residents were posted with the various native sultanates on major islands; they were all three subordinated to the French administrators of Mayotte island protectorate (itself constituting the native Maore or Mawuti sultanate):

o On Ngazidja (Grande Comore island, divided in eleven sultanates, some of which on occasion had the superior title of Sultani tibe): November 1886 – 1912

o On Ndzuwani (Anjouan island) with the Phany (sole Sultan): only two incumbents 188x–189x

o On Mwali (Mohéli island) from 1886; then 1889–1912 filled by the above résidents of Anjouan

• On Wallis and Futuna, after a single French Representative styled chargé de mission (7 April 1887 – 26 June 1888, Maurice Antoine Chauvot), there was a long list of Residents from 7 April 1887; since 3 October 1961, when both islands were joined as the Wallis & Futuna overseas territory, their successors were styled Administrateur supérieur 'Administrator-superior', but the native dynasties remain; they represented the French government by virtue of the protectorate treaties with the Tui (ruler) of `Uvea (Wallis island, 5 April 1887; 27 November 1887 administratively attached to New Caledonia) and on 16 February 1888 with the two kingdoms on Futuna—Tu`a (also called Alo) and Sigave

Résident supérieur

This French title, meaning "Superior" (i.e. Senior) Resident, indicates that he had junior Residents under him.

• In Upper Volta (present Burkina Faso), which has had its own Lieutenant governor (before) or Governor (after) and intermediately has been part of one or (carved up) more neighbouring French colonies, there has been one Résident-Superieur of "Upper Ivory Coast", 1 January 1938 - 29 July 1940, while it was part of the Ivory Coast colony: Edmond Louveau

• In Cambodia, where the local royal government was theoretically maintained, the resident at Phnom-Penh was the Resident-Superior, over the various Residents posted throughout Cambodia. The Resident-Superior of Cambodia answered to the Governor-General of Indochina, however.

German colonial residents

In the German colonies, the title was also Resident; the post was called Residentur.

• in Wituland: Ahmed ibn Fumo Bakari, the first mfalume (sultan) of Witu (on the Kenyan coast), ceded 25 square miles (65 km2) of territory on 8 April 1885 to the brothers Clemens and Gustav Denhardt's “Tana Company”, and the remainder of the Wituland became the German Schutzgebiet (Protectorate) of Wituland (Deutsch-Witu) on 27 May 1885. The Reich was represented there by the German Residents: Gustav Denhardt (b. 1856 – d. 1917; in office 8 April 1885 – 1 July 1890) and his deputy Clemens Andreas Denhardt (b. 1852 – d. 1928) until on 1 July 1890 imperial Germany renounces its protectorate, ceding the Wituland to Great Britain which had on 18 June 1890 declared it a British protectorate).

• in German East Africa

o Resident of Ruanda: 1906 – 15 November 1907 Werner von Grawert (d. 1918), formerly the last military district commander of Usumbura (the other district being Ujiji)

o Resident of Urundi (present Burundi): 15 November 1907 – June 1916, starting with the same as above; formally accredited to the native Mwami (King; on 8 October 1905 the Germans recognized the already ruling Mwezi IV Gisabo as "Sultan" of Burundi and its only supreme authority)

o Resident of Bukoba west of Lake Victoria overseeing an area of 32,200 km²;

• in German Kamerun

o Resident of Garua

o Resident of Mora

o Resident of Ngaundere

• in German South-West Africa (present Namibia)

o Resident of Schuckmannsburg for the Caprivi Strip.

Portuguese colonial residents

• In Cabinda (in present Angola), five incumbents from 1885 (18 July 1885 Portuguese Congo district created after 14 February 1885 confirmation by the Berlin Conference of the 1883 Portuguese protectorate over "Portuguese Congo") to 1899 (end of autonomy under the Governors of Congo district which had its seat in Cabinda since 1887)

• In the Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá (in present Benin), civil residents served from 1911 (withdrawal of the Portuguese military garrison) until 31 July 1961 (invasion of the fort by the Benin military forces)

Residents-general (and their subordinate residents)

British resident (-general)

British Malay states and possessions

At the "national" level of British Malaya, after the post of High Commissioner had been filled (1 July 1896 – 1 April 1946) by the governors of the Straits Settlements (see Singapore), Britain appointed the following residents-general:

• 1 July 1896 – 1901 Frank Athelstane Swettenham (b. 1850 – d. 1946; from 1897, Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham)

• 1901–1904 William Hood Treacher (b. 1849 – d. 1919)

• 1904–1910 Sir William Thomas Taylor (b. 1848 – d. 1931)

• 1910–1911 Arthur Henderson Young (b. 1854 – d. 1938)

Then there were various British chief secretaries 1911–1936 and two federal secretaries until 31 January 1942; after three Japanese military governors, the British Governor (1 April 1946 – 1 February 1948) stayed on as first of four High Commissioners as de facto governor-general of the Federation of Malaya until independence on 31 August 1957 saw the creation of an elective federal paramount ruler styled Yang Dipertuan Agong (since 16 September 1961 with the addition bagi Malaysia).

There were specific residents accredited in most constituent Malay states:

• 1885–1911 British Residents were appointed to the Sultans (until 1886 styled Maharaja) of Johore, an unfederated state until 1946; thereafter the British crown was represented by General Advisers until the Japanese occupation, finally by Commissioners 1945–1948

• 1888–1941 to the Yang Di Pertuan Besar (state's elective ruler) of the nine member-confederation Negeri Sembilan, which accepted a British protectorate in 1888 and acceded in 1896 to the Federation; again British Commissioners after the Japanese occupation

o 1883–1895 additional British Residents were appointed to the Yang Di-Pertuan Muda (ruler) of Jelebu, a major member principality

o 1875–1889 additional British Residents were also appointed to the Undang Luak Sungai Ujong (ruler) of Sungai Ujong, another major member principality

• 1888–1938 British Residents were appointed to the Sultans (until 1882 styled Bendahara Seri Maharaja) of Pahang from the start of the British protectorate; again British Commissioners after the Japanese occupation

• 1874–1941 British Residents to the Sultans of Perak as written in the Pangkor Treaty of 1874, since they exchanged Thai sovereignty for a British protectorate; since 1 July 1896 part of the Federated Malay States; after the Japanese occupation a single British Commissioner

• 1875–1941 British Residents to the Sultans of Selangor during the Klang War, a year after accepting British protectorate (never under Thailand), 1 July 1896 part of Federated Malay States; after the Japanese occupation British Commissioners

A similar position, under another title, was held in the other Malay states:

• 1909–41 British Advisers replaced the Thai king's Advisers in the sultanate of Kedah, an unfederated state; after Japanese and Thai occupation, British Commissioners were appointed

• 1903–41 British Advisers replaced Thai ones in the sultanate of Kelantan, an unfederated state; after Japanese and Thai occupation, British Commissioners were appointed

• 1909–1941 British Advisers replaced Thai ones with the Rajas of Perlis, since the acceptance of British protectorate as an unfederated state instead of the Thai sovereignty (since the secession from Kedah) and were appointed again after Japanese and Thai occupation, until 1 April 1946 it joins the Malay Union (from 16 September 1963, Malaysia)

• 1904–25 British Agents were appointed to the Sultans of Terengganu, i.e. even before the 9 July 1909 exchange of Thai sovereignty for a British protectorate as unfederated Malay state, then Advisers 1919–1941 (overlap merely both titles for the same incumbent); after Japanese and Thai occupation, British Commissioners were appointed.

In the Straits Settlements, under direct British rule:

• in Singapore, after two separate British Residents (7 February 1819 – December 1822 William Farquhar, then John Crawfurd), the Governors of the Straits Settlements filled the post 1826 – 15 February 1942; after four Japanese Military Administrators and two Japanese Mayors, a British Military Administrator 12 September 1945 – 1 April 1946, then four British Governors and the second incumbent stayed on as first of two gubernatorial 'Heads of state' styled yang di-pertuan negara, his Malay successor also becoming the first President after independence

• In Malacca (Melaka), a former Dutch colony, seven consecutive British Residents were in office 1795–1818, followed by three Dutch governors; after the final inclusion in the British Strait Settlements, 1826, most were titled Resident Councillor, except the period 1910–1920 reverting to the style Resident; after the Japanese occupation, Resident Commissioners took their place until the 1957 independence installed Malaysian Governors and Chief Ministers

• In Penang (Pinang), after three Superintendents for the British East India Company (1786–1799; only Prince of Wales Island had yet been ceded to the British by the Sultan of Kedah), then two Lieutenant-governors (in 1801 Province Wellesley on the mainland was added) and many Governors after 1805 (since 1826 as part of the Strait Settlements), only Resident Councillors were in office 1849–1941 (name Penang assumed in 1867); after four Japanese and since 1945 two British military governors, four Resident Commissioners 1946–1957, since then Malaysian-appointed "heads of state".

On Northern Borneo, contrary to the Malay peninsula, no such officials were appointed, in Sarawak and Sabah as there were white rulers or governors; but to the still sovereign Sultans of Brunei, lying between those larger states, British Residents were appointed 1906–1959 (interrupted by Japanese commander Masao Baba 6 January 1942 – 14 June 1945), afterwards only High Commissioners for the matters not transferred under autonomy (and 1971 self-government) until full independence went in force 1 January 1984. The administrative head of Sarawak's geographical Divisions was, however, titled as Resident.

French

The French word is Résident-général.

Africa

• In Morocco, accredited with the Sultan: Residents-general 28 April 1912 – 2 March 1956 (first incumbent previously military governor)

• In Tunisia, accredited with the Basha Bey Residents-general 23 June 1885 – 31 August 1955; first incumbent was the last of the two previous Resident ministers

• On Madagascar: 28 April 1886 – 31 July 1897

Indochina[edit]

• In present Vietnam & Laos: Residents-general for Annam-Tonkin (at Hué) 11 June 1884 – 9 May 1889

o Residents-Superior for Annam (also at Hué) 1886–1950s (at least 1953)

o Residents-Superior for Tonkin (at Hanoi; subordinated to Annam until 1888) 1886–1950s (at least 1953)—but none in Cochinchina

o Residents-superior for Laos September 1895 – 5 April 1945

• In Cambodia Residents-general 12 August 1885 – 16 May 1889;

o later downgraded (under Hué) to Residents-superior 16 May 1889 – 15 October 1945

o several regional Résidents

Belgian

(Belgium mainly used French in the colonies; the word in its other official language, Dutch, is Resident-generaal)

• Ruanda-Urundi (cfr. German above; there were Belgian Residents ): 1960 – 1 July 1962 Jean-Paul Harroy (b. 1909 – d. 1995), staying on after being its Belgian last Governor (and Deputy Governor-General of the Belgian Congo)

Japanese (original title)

In the protectorate Korea, accredited to the Choson Monarch (rendered as King or Emperor) 21 Dec 1905 – 1 Oct 1910 three incumbents (including Hirobumi Ito the former Prime Minister of Japan), all Japanese peers (new western-type styles, rendered as: Marquess/Duke or Viscount); the last stayed on as the first Governor-General after full annexation to Japan. See: List of Japanese Residents-General of Korea

Postcolonial residents

On occasion, residents were maintained, notably by former colonial powers, in territories in a transitional process to a new constitutional status, such as full independence. Such function could also be performed under another title, such as Commissioner or High Commissioner.

Thus after World War I, there were residents in some mandate territories:

• after the French and British occupation of the former German colony Kamerun (since 26 September 1914), Britain started appointing a long line of residents (some were district officer or senior district officer, others deputy resident or senior resident) in its zone from 1916, even before the 28 June 1919 formal division into French and British Cameroons and the 20 July 1920 British Cameroons, League of Nations mandate; they continued in the 13 December 1946 created British Cameroons United Nations trust territory, until 31 December 1949; next a single special resident was appointed (although in 1949 Southern Cameroons was divided into two provinces: Bamenda, capital Bamenda, and Southern, capital Buea) until 1 October 1954 when British Cameroons became an autonomous part of Nigeria; next two commissioners were appointed instead, until on 1 October 1961 Southern British Cameroons was incorporated into the Republic of Cameroon (the former French Cameroun), the northern part was already united with Nigeria on 1 June 1961.

• Present Jordan was part since 12 May 1920 of the British mandate of Palestine (under a British high commissioner), but in August 1920 the British create autonomous local administrations in Ajlun, Salt, and Karak—with limited success; 11 April 1921 the Emirate of Transjordan (under British mandate); 26 May 1923 Transjordan formally separated from Palestine; 28 Feb 1928 Britain recognizes Transjordan mandate as independent, but maintains military and some financial control; 25 May 1946 proclamation of the Hashemite Kingdom (style Malik) of Transjordan (present Jordan); the 17 June 1946 formal independence from Britain finally ends the term of the last of four British Residents:

o April 1921 – 21 November 1921 Albert Abramson (b. 1876 – d. 19..)

o 21 November 1921 – April 1924 Harry St. John Bridger Philby (b. 1885 – d. 1960)

o August 1924 – March 1939 Henry Cox (from 1937, Charles Henry Cox) (b. 1880 – d. 1953)

o March 1939 – 17 June 1946 Alec Seath Kirkbride (b. 1897 – d. 1978)

Also after World War II, and not only in former mandate territories; e.g. in parts of Libya, a former Italian colony, put under UN administration since 1946 prior to their unification as a Libyan kingdom, Britain maintained a Resident in Tripolitania April 1949 – 24 December 1951 and another in Cyrenaica 17 September 1949 – 24 December 1951, and France one in Fezzan 1950 – 24 December 1951.

In a later phase a former colony could itself appoint such Residents, as India did 5 December 1950 – 16 May 1975 in its Himalayan protectorate Sikkim, then still an independent monarchy (afterwards absorbed into India as an additional constitutive state) where Britain had obtained a protectorate over the Maharaja in 1861, see above.

Government residents in Australia

Western Australia

In the Colony of Western Australia, colonial administration and local government were sometimes controlled at the regional level, by government residents, under the direction of the Colonial Secretary (i.e. the "Governor in Council").

The main responsibility of a government resident was the role of Resident Magistrate, and the two titles were often used interchangeably. However, they also often directed the day-to-day activities of police, explorers, surveyors, customs officers and other public servants. Government residents were appointed (at various times), at Augusta, Busselton, Carnarvon (Gascoyne District), Champion Bay (Geraldton), Derby (Kimberley District, later West Kimberley), Fremantle, Guildford, King George's Sound (Albany), Newcastle (Toodyay), the North District (Camden Harbour/Roebourne), Port Leschenault (Bunbury), Wyndham (East Kimberley) and York.

Northern Territory

In the Northern Territory, government residents were appointed by the Government of South Australia from the establishment of the territory in 1864 until its transfer to the Australian Government on 1 January 1911.[3] The last incumbent stayed on as first of six administrators; then again 1 February 1927 Robert Hunter Weddell was Government Resident for North Australia, until from 12 June 1931. Administrators were (and still are) appointed, even after 1978 when self-government was granted.

Central Australia

1 March 1927 – 12 June 1931, while the Northern Territory was split, there were two consecutive incumbents for Central Australia.

Other uses

• In espionage, resident (or rezident) may be used to refer to the head or representative of a country's intelligence services in a foreign country, often within an Embassy.

• In the U.S. and Canada, the term "chief resident" applies to a physician who is appointed to act as head of the residents in his or her hospital, program or department.

See also

• Resident Commissioner

• Political Resident

References

1. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Resident" . Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 183.

2. Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh commemorates his name; Cox also figures among historians of chess: see the now-discredited Cox-Forbes theory.

3. "The Northern Territory Act 1863 No. 23" (PDF). Government of South Australia. 12 November 1863. pp. 275 and 278–279. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

Sources and references

• WorldStatesmen here India—see also its Princely States and other present countries mentioned or the pages for polities there

• RoyalArk various mentions, usually in the extensive genealogies, in various states