by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/11/19

The Milner Group could never have been built up by Milner's own efforts. He had no political power or even influence. All that he had was ability and ideas. The same thing is true about many of the other members of the Milner Group, at least at the time that they joined the Group. The power that was utilized by Milner and his Group was really the power of the Cecil family and its allied families such as the Lyttelton (Viscounts Cobham), Wyndham (Barons Leconfield), Grosvenor (Dukes of Westminster), Balfour, Wemyss, Palmer (Earls of Selborne and Viscounts Wolmer), Cavendish (Dukes of Devonshire and Marquesses of Hartington), and Gathorne-Hardy (Earls of Cranbrook). The Milner Group was originally a major fief within the great nexus of power, influence, and privilege controlled by the Cecil family. It is not possible to describe here the ramifications of the Cecil influence. It has been all-pervasive in British life since 1886. This Cecil Bloc was built up by Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, Viscount Cranborne and third Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903). The methods used by this man were merely copied by the Milner Group. These methods can be summed up under three headings: (a) a triple-front penetration in politics, education, and journalism; (b) the recruitment of men of ability (chiefly from All Souls) and the linking of these men to the Cecil Bloc by matrimonial alliances and by gratitude for titles and positions of power; and (c) the influencing of public policy by placing members of the Cecil Bloc in positions of power shielded as much as possible from public attention.

The triple-front penetration can be seen in Lord Salisbury's own life. He was not only Prime Minister for a longer period than anyone else in recent history (fourteen years between 1885 and 1902) but also a Fellow of All Souls (from 1853) and Chancellor of Oxford University (1869-1903), and had a paramount influence on The Quarterly Review for many years. He practiced a shameless nepotism, concealed to some extent by the shifting of names because of acquisition of titles and female marital connections, and redeemed by the fact that ability as well as family connection was required from appointees...

The Cecil Bloc did not disappear with the death of Lord Salisbury in 1903 but was continued for a considerable period by Balfour. It did not, however, continue to grow but, on the contrary, became looser and less disciplined, for Balfour lacked the qualities of ambition and determination necessary to control or develop such a group. Accordingly, the Cecil Bloc, while still in existence as a political and social power, has largely been replaced by the Milner Croup. This Group, which began as a dependent fief of the Cecil Bloc, has since 1916 become increasingly the active portion of the Bloc and in fact its real center. Milner possessed those qualities of determination and ambition which Balfour lacked, and was willing to sacrifice all personal happiness and social life to his political goals, something which was quite unacceptable to the pleasure-loving Balfour. Moreover, Milner was intelligent enough to see that it was not possible to continue a political group organized in the casual and familiar way in which it had been done by Lord Salisbury. Milner shifted the emphasis from family connection to ideological agreement. The former had become less useful with the rise of a class society based on economic conflicts and with the extension of democracy. Salisbury was fundamentally a conservative, while Milner was not. Where Salisbury sought to build up a bloc of friends and relatives to exercise the game of politics and to maintain the Old England that they all loved, Milner was not really a conservative at all. Milner had an idea — the idea he had obtained from Toynbee and that he found also in Rhodes and in all the members of his Group. This idea had two parts: that the extension and integration of the Empire and the development of social welfare were essential to the continued existence of the British way of life; and that this British way of life was an instrument which unfolded all the best and highest capabilities of mankind. Working with this ideology derived from Toynbee and Balliol, Milner used the power and the general strategic methods of the Cecil Bloc to build up his own Group. But, realizing that conditions had changed, he put much greater emphasis on propaganda activities and on ideological unity within the Group. These were both made necessary by the extension of political democracy and the rise of economic democracy as a practical political issue. These new developments had made it impossible to be satisfied with a group held together by no more than family and social connections and animated by no more far-sighted goal than the preservation of the existing social structure.

The Cecil Bloc did not resist this change by Milner of the aims and tactics of their older leader. The times made it clear to all that methods must be changed. However, it is possible that the split which appeared within the Conservative Party in England after 1923 followed roughly the lines between the Milner Group and the Cecil Bloc.

It should perhaps be pointed out that the Cecil Bloc was a social rather than a partisan group — at first, at least. Until 1890 or so it contained members of both political parties, including the leaders, Salisbury and Gladstone. The relationship between the two parties on the topmost level could be symbolized by the tragic romance between Salisbury's nephew and Gladstone's niece, ending in the death of the latter in 1875. After the split in the Liberal Party in 1886, it was the members of the Cecil Bloc who became Unionists — that is, the Lytteltons, the Wyndhams, the Cavendishes. As a result, the Cecil Bloc became increasingly a political force. Gladstone remained socially a member of it, and so did his protege, John Morley, but almost all the other members of the Bloc were Unionists or Conservatives. The chief exceptions were the four leaders of the Liberal Party after Gladstone, who were strong imperialists: Rosebery, Asquith, Edward Grey, and Haldane. These four supported the Boer War, grew increasingly anti-German, supported the World War in 1914, and were close to the Milner Group politically, intellectually, and socially...

Socially, the Cecil Bloc could be divided into three generations. The first (including Salisbury, Gladstone, the seventh Duke of Devonshire, the eighth Viscount Midleton, Goschen, the fourth Baron Lyttelton, the first Earl of Cranbrook, the first Duke of Westminster, the first Baron Leconfield, the tenth Earl of Wemyss, etc.) was not as "social" (in the frivolous sense) as the second. This first generation was born in the first third of the nineteenth century, went to both Oxford and Cambridge in the period 1830-1855, and died in the period 1890-1915. The second generation was born in the second third of the nineteenth century, went almost exclusively to Oxford (chiefly Balliol) in the period 1860-1880, and died in the period 1920-1930. This second generation was much more social in a spectacularly frivolous sense, much more intellectual (in the sense that they read books and talked philosophy or social problems) and centered on a social group known at the time as "The Souls." The third generation of the Cecil Bloc, consisting of persons born in the last third of the nineteenth century, went to Oxford almost exclusively (New College or Balliol) in the period 1890-1905 and began to die off about 1940. This third generation of the Cecil Bloc was dominated and organized about the Milner Group. It was very serious-minded, very political, and very secretive.

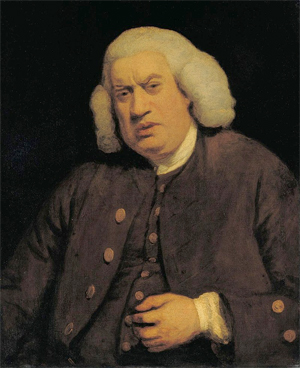

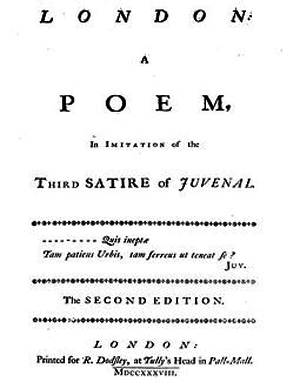

The first two generations did not regard themselves as an organized group but rather as "Society." The Bloc was symbolized in the first two generations in two exclusive dining clubs called "The Club" and "Grillion's." The membership of the two was very similar, with about forty persons in each and a total of not over sixty in both together. Both organizations had illustrious pasts. The Club, founded in 1764, had as past members Joshua Reynolds (founder), Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, James Boswell, Edward Gibbon, Charles Fox, David Garrick, Adam Smith, Richard B. Sheridan, George Canning, Humphry Davy, Walter Scott, Lord Liverpool, Henry Hallam, Lord Brougham, T. B. Macauley, Lord John Russell, George Grote, Dean Stanley, W. E. H. Lecky, Lord Kelvin, Matthew Arnold, T. H. Huxley, Bishop Wilberforce, Bishop Stubbs, Bishop Creighton, Gladstone, Lord Salisbury, Balfour, John Morley, Richard Jebb, Lord Goschen, Lord Acton, Lord Rosebery, Archbishop Lang, F. W. Pember (Warden of All Souls), Lord Asquith, Edward Grey, Lord Haldane, Hugh Cecil, John Simon, Charles Oman, Lord Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Murray, H. A. L. Fisher, John Buchan, Maurice Hankey, the fourth Marquess of Salisbury, Lord Lansdowne, Bishop Henson, Halifax, Stanley Baldwin, Austen Chamberlain, Lord Carnock, and Lord Hew art. This list includes only members up to 1925. There were, as we have said, only forty members at any one time, and at meetings (dinner every fortnight while Parliament was in session) usually only about a dozen were present.

Grillion's was very similar to The Club. Founded in 1812, it had the same members and met under the same conditions, except weekly (dinner when Parliament was in session). The following list includes the names I can find of those who were members up to 1925: Gladstone, Salisbury, Lecky, Balfour, Asquith, Edward Grey, Haldane, Lord Bryce, Hugh Cecil, Robert Cecil, Curzon, Neville Lyttelton, Eustace Percy, John Simon, Geoffrey Dawson, Walter Raleigh, Balfour of Burleigh, and. Gilbert Murray.(8)

The second generation of the Cecil Bloc was famous at the time that it was growing up (and political power was still in the hands of the first generation) as "The Souls," a term applied to them partly in derision and partly in envy but used by themselves later. This group, flitting about from one great country house to another or from one spectacular social event to another in the town houses of their elders, has been preserved for posterity in the autobiographical volumes of Margot Tennant Asquith and has been caricatured in the writings of Oscar Wilde. The frivolity of this group can be seen in Margot Tennant's statement that she obtained for Milner his appointment to the chairmanship of the Board of Inland Revenue in 1892 merely by writing to Balfour and asking for it after she had a too brief romantic interlude with Milner in Egypt. As a respected scholar of my acquaintance has said, this group did everything in a frivolous fashion, including entering the Boer War and the First World War.

One of the enduring creations of the Cecil Bloc is the Society for Psychical Research, which holds a position in the history of the Cecil Bloc similar to that held by the Royal Institute of International Affairs in the Milner Group. The Society was founded in 1882 by the Balfour family and their in-laws, Lord Rayleigh and Professor Sidgwick. In the twentieth century it was dominated by those members of the Cecil Bloc who became most readily members of the Milner Group. Among these we might mention Gilbert Murray, who performed a notable series of experiments with his daughter, Mrs. Arnold J. Toynbee, in the years before 1914, and Dame Edith Lyttelton, herself a Balfour and widow of Arthur Balfour's closest friend, who was president of the Society in 1933-1934.

The third generation was quite different, partly because it was dominated by Milner, one of the few completely serious members of the second generation. This third generation was serious if not profound, studious if not broadly educated, and haunted consistently by the need to act quickly to avoid impending disaster. This fear of disaster they shared with Rhodes and Milner, but they still had the basic weakness of the second generation (except Milner and a few other adopted members of that Group), namely that they got everything too easily. Political power, wealth, and social position came to this third generation as a gift from the second, without the need to struggle for what they got or to analyze the foundations of their beliefs. As a result, while awake to the impending disaster, they were not able to avoid it, but instead tinkered and tampered until the whole system blew up in their faces.

This third generation, especially the Milner Group, which formed its core, differed from its two predecessors in its realization that it formed a group. The first generation had regarded itself as "England," the second regarded itself as "Society," but the third realized it was a secret group — or at least its inner circles did. From Milner and Rhodes they got this idea of a secret group of able and determined men, but they never found a name for it, contenting themselves with calling it "the Group," or "the Band," or even "Us."...

In each of his seven wills, Rhodes entrusted his bequest to a group of men to carry out his purpose. In the first will, as we have seen, the trustees were Lord Carnarvon and Sidney Shippard. In the second will (1882), the sole trustee was his friend N. E. Pickering. In the third will (1888), Pickering having died, the sole trustee was Lord Rothschild. In the fourth will (1891), W. T. Stead was added, while in the fifth (1892), Rhodes's solicitor, B. F. Hawksley, was added to the previous two. In the sixth (1893) and seventh (1899) wills, the personnel of the trustees shifted considerably, ending up, at Rhodes's death in 1902, with a board of seven trustees: Lord Milner, Lord Rosebery, Lord Grey, Alfred Beit, L. L. Michell, B. F. Hawksley, and Dr. Starr Jameson. This is the board to which the world looked to set up the Rhodes Scholarships...

Another prominent political figure who may have been an initiate in the period before 1902 is Lord Rosebery. Like his father-in-law, Lord Rothschild, who was an initiate, Rosebery was probably not a very active member of The Society of the Elect, although for quite different reasons. Lord Rothschild held aloof because to him the whole project was incomprehensible and unbusinesslike; Lord Rosebery held aloof because of his own diffident personality and his bad physical health. However, he cooperated with the members of the society and was on such close personal relationships with them that he probably knew of the secret society. Brett was one of his most intimate associates and introduced him to Milner in 1885. As for Rhodes, Rosebery's official biographer, the Marquess of Crewe, says that he "both liked and admired Cecil Rhodes who was often his guest." He made Rhodes a Privy Councillor, and Rhodes made him a trustee of his will. These things, and the fact that the initiates generally assumed that Rosebery would grant their requests, give certain grounds for believing that he was a member of their society. If he was, he played little role in it after 1900.

-- The Anglo-American Establishment: From Rhodes to Cliveden, by Carroll Quigley

The Right Honourable, The Earl of Rosebery, KG KT PC FRS FBA

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

In office: 5 March 1894 – 22 June 1895

Monarch: Victoria

Preceded by: William Ewart Gladstone

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Salisbury

Leader of the Opposition

In office: 22 June 1895 – 6 October 1896

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: The Marquess of Salisbury

Preceded by: The Marquess of Salisbury

Succeeded by: Sir William Harcourt

Lord President of the Council

In office: 10 March 1894 – 21 June 1895

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: Himself

Preceded by: The Earl of Kimberley

Succeeded by: The Duke of Devonshire

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

In office: 18 August 1892 – 10 March 1894

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: William Ewart Gladstone

Preceded by: The Marquess of Salisbury

Succeeded by: The Earl of Kimberley

In office

6 February 1886 – 3 August 1886

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: William Ewart Gladstone

Preceded by: The Marquess of Salisbury

Succeeded by: The Earl of Iddesleigh

Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

In office: 5 March 1885 – 9 June 1885

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: William Ewart Gladstone

Preceded by: The Lord Carlingford

Succeeded by: The Earl of Harrowby

First Commissioner of Works

In office: 13 February 1885 – 9 June 1885

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: William Ewart Gladstone

Preceded by: George Shaw-Lefevre

Succeeded by: David Plunket

Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department

In office: August 1881 – June 1883

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: William Ewart Gladstone

Preceded by: Leonard Courtney

Succeeded by: J. T. Hibbert

Member of the House of Lords, Lord Temporal

In office: 7 May 1868 – 21 May 1929

Hereditary peerage

Preceded by: The 4th Earl of Rosebery

Succeeded by: The 6th Earl of Rosebery

Personal details

Born: Archibald Philip Primrose, 7 May 1847, Mayfair, Middlesex, England

Died: 21 May 1929 (aged 82), Epsom, Surrey, England

Resting place: Dalmeny Parish Church, Edinburgh, Scotland

Political party: Liberal

Spouse(s): Hannah de Rothschild (m. 1878; died 1890)

Children: 4, including Sybil, Harry, and Neil

Parents: Archibald Primrose, Lord Dalmeny

Wilhelmina Powlett, Duchess of Cleveland

Alma mater: Christ Church, Oxford

Garter encircled shield of arms of Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, KG, as displayed on his Order of the Garter stall plate in St. George's Chapel, viz. Quarterly, 1st and 4th, vert three primroses within a double tressure flory counterflory or, for PRIMROSE; 2nd and 3rd, argent a lion rampant double-queued sable, for CRESSY.

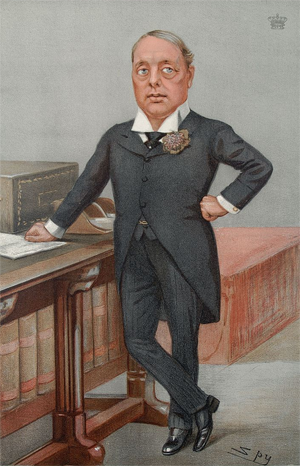

Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, 1st Earl of Midlothian, KG, KT, PC, FRS, FBA (7 May 1847 – 21 May 1929), was a British Liberal politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from March 1894 to June 1895. Between the death of his father, in 1851, and the death of his grandfather, the 4th Earl of Rosebery, in 1868 he was known by the courtesy title of Lord Dalmeny.

Rosebery first came to national attention in 1879 by sponsoring the successful Midlothian campaign of William Ewart Gladstone. He briefly was in charge of Scottish affairs. His most successful performance in office came as chairman of the London County Council in 1889. He entered the cabinet in 1885 and served twice as foreign minister, paying special attention to French and German affairs. He succeeded Gladstone as prime minister and leader of the Liberal Party in 1894; the Liberals lost the 1895 election. He resigned the party leadership in 1896 and never again held political office.

Rosebery was widely known as a brilliant orator, an outstanding sportsman and marksman, a writer and historian, connoisseur and collector. All of these activities attracted him more than politics, which grew boring and unattractive. Furthermore, he drifted to the right of the Liberal party and became a bitter critic of its policies. Winston Churchill, observing that he never adapted to democratic electoral competition, quipped: "He would not stoop; he did not conquer."[1]

Rosebery was a Liberal Imperialist who favoured strong national defence and imperialism abroad and social reform at home, while being solidly anti-socialist. Historians judge him a failure as foreign minister[2] and as prime minister.[3][4]

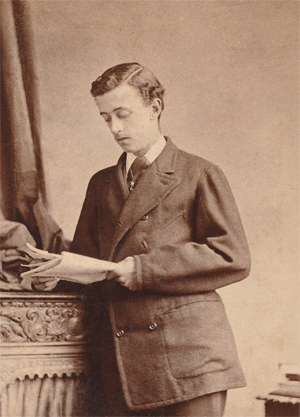

Origins and early life

Archibald Philip Primrose was born on 7 May 1847 in his parents' house in Charles Street, Mayfair, London.[5] His father was Archibald Primrose, Lord Dalmeny (1809–1851), son and heir apparent to Archibald Primrose, 4th Earl of Rosebery (1783–1868), whom he predeceased. Lord Dalmeny was a courtesy title used by the Earl's eldest son and heir apparent, during the Earl's lifetime, and was one of the Earl's lesser Scottish titles. Lord Dalmeny (died 1851) was MP for Stirling from 1832 to 1847 and served as First Lord of the Admiralty under Lord Melbourne.[6]

Rosebery's mother was Lady (Catherine Lucy) Wilhelmina Stanhope (1819–1901), a historian who later wrote under her second married name "the Duchess of Cleveland", a daughter of Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl Stanhope. Lord Dalmeny died on 23 January 1851, having predeceased his father, when the courtesy title passed to his son, the future Rosebery, as the new heir to the earldom.[7] In 1854 his mother remarried to Lord Harry Vane (later after 1864 known as Harry Powlett, 4th Duke of Cleveland).[8] The relationship between mother and son was very poor. His elder and favourite sister Lady Leconfield was the wife of Henry Wyndham, 2nd Baron Leconfield.[9]

Education and youth

Dalmeny attended preparatory schools in Hertfordshire and Brighton, and then Eton College (1860–65[10]). At Eton, he formed a close attachment to his tutor William Johnson Cory: they visited Rome together in 1864, and maintained correspondence for years afterwards.[11] Dalmeny proceeded to Christ Church, Oxford, matriculating in January 1866.[12] He left Oxford in 1868:[13] Dalmeny bought a horse named Ladas, although a rule banned undergraduates from owning horses. When he was found out, he was offered a choice: to sell the horse or to give up his studies. He chose the latter, and subsequently was a prominent figure in British horseracing for 40 years.

The three Prime Ministers from 1880 to 1902, namely Gladstone, Salisbury and Rosebery, all attended both Eton and Christ Church.

Rosebery toured the United States in 1873, 1874 and 1876. He was pressed to marry Marie Fox, the sixteen-year-old adopted daughter of Henry Fox, 4th Baron Holland. She declined him and later married Prince Louis of Liechtenstein.

Succession to earldom

When his grandfather died in 1868, Dalmeny became 5th Earl of Rosebery. The earldom did not however entitle Archibald Primrose to sit in the House of Lords, nor disqualify him from sitting in the House of Commons, as the title is part of the old Peerage of Scotland, from which 16 members (representative peers) were elected to sit in the Lords for each session of Parliament. However, in 1828, Rosebery's grandfather had been created 1st Baron Rosebery in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, which did entitle Rosebery to sit in the Lords like all peers of the United Kingdom, and barred him from a career in the House of Commons.[citation needed]

Career

Rosebery is reputed to have said that he had three aims in life: to win the Derby, to marry an heiress, and to become Prime Minister.[14] He managed all three.

Early political career

At Eton, Rosebery notably attacked Charles I of England for his despotism, and went on to praise his Whig forebears – his ancestor, James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope, was a minister to George I of Great Britain. Benjamin Disraeli often met with Rosebery in the 1870s to try to recruit him for his party, but this proved futile. Disraeli's major rival, William Ewart Gladstone, also pursued Rosebery, with considerable success.

As part of the Liberal plan to get Gladstone to be MP for Midlothian, Rosebery sponsored and largely ran the Midlothian Campaign of 1879. He based this on what he had observed in elections in the United States. Gladstone spoke from open-deck trains, and gathered mass support. In 1880, he was duly elected Member for Midlothian and returned to the premiership.[15][16]

Rosebery served as Foreign Secretary in Gladstone's brief third ministry in 1886. He served as the first chairman of the London County Council, set up by the Conservatives in 1889. Rosebery Avenue in Clerkenwell is named after him.[17][18]

He served as President of the first day of the 1890 Co-operative Congress.[19]

Rosebery's second period as Foreign Secretary, 1892–1894, predominantly involved quarrels with France over Uganda. To quote his hero Napoleon, Rosebery thought that "the Master of Egypt is the Master of India"; thus he pursued the policy of expansion in Africa.[citation needed]

Rosebery helped Gladstone's Second Home Rule Bill in the House of Lords; nevertheless it was defeated overwhelmingly in the autumn of 1893.[20] The first bill had been defeated in the House of Commons in 1886.[21]

Prime Minister

Further information: Rosebery ministry

Rosebery became a leader of the Liberal Imperialist faction of the Liberal Party and when Gladstone retired, in 1894, Rosebery succeeded him as Prime Minister, much to the disgust of Sir William Harcourt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the more left-wing Liberals. Rosebery's selection was largely because Queen Victoria disliked most of the other leading Liberals. Rosebery was in the Lords, but Harcourt controlled the Commons, where he often undercut the prime minister. Rosebery was the only one of the ten Prime Ministers to serve during Queen Victoria's reign who was born after her accession to the throne in 1837.

Rosebery's government was largely unsuccessful, as in the Armenian crisis of 1895–96. He spoke out for a strongly pro-Armenian and anti-Turkish policy.[22] Gladstone, a prime minister in retirement, called on Britain to intervene alone. The added pressure weakened Rosebery.[23]

His designs in foreign policy, such as expansion of the fleet, were defeated by disagreements within the Liberal Party. He angered all the European powers.[24]

The Unionist-dominated House of Lords stopped the whole of the Liberals' domestic legislation. The strongest figure in the cabinet was Rosebery's rival, Harcourt.[citation needed] He and his son Lewis were perennial critics of Rosebery's policies. There were two future prime ministers in the Cabinet, Home Secretary H. H. Asquith, and Secretary of State for War Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Rosebery rapidly lost interest in running the government. In the last year of his premiership, he was increasingly haggard: he suffered insomnia due to the continual dissension in his Cabinet.[citation needed]

On 21 June 1895, the government lost a vote in committee on army supply by just seven votes. While this might have been treated merely as a vote of no confidence in Secretary for War Campbell-Bannerman, Rosebery chose to treat it as a vote of censure on his government. On 22 June, he and his ministers tendered their resignations to the Queen, who invited the Unionist leader, Lord Salisbury, to form a government. The following month, the Unionists won a crushing victory in the 1895 general election, and held power for ten years (1895–1905) under Salisbury and Arthur Balfour. Rosebery remained the Liberal leader for another year, then permanently retired from politics.

Lord Rosebery's government, March 1894 – June 1895

• Lord Rosebery – First Lord of the Treasury, Lord President of the Council, and Leader of the House of Lords

• Lord Herschell – Lord Chancellor

• Lord Tweedmouth – Lord Privy Seal

• H. H. Asquith – Secretary of State for the Home Department

• Lord Kimberley – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

• Lord Ripon – Secretary of State for the Colonies

• Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman – Secretary of State for War

• Sir Henry Hartley Fowler – Secretary of State for India

• Sir William Harcourt – Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons

• Lord Spencer – First Lord of the Admiralty

• Anthony John Mundella – President of the Board of Trade

• Arnold Morley – Postmaster-General

• George John Shaw-Lefevre – President of the Local Government Board

• James Bryce – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

• John Morley – Chief Secretary for Ireland

• Sir George Otto Trevelyan – Secretary for Scotland

• Sir Arthur Herbert Dyke Acland – Vice-President of the Council

Changes

• May 1894: James Bryce succeeds A. J. Mundella at the Board of Trade. Lord Tweedmouth succeeds Bryce at the Duchy of Lancaster, remaining also Lord Privy Seal.

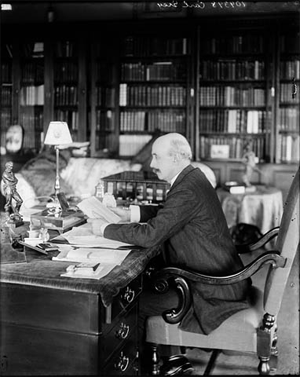

Later life

Rosebery caricatured by Spy for Vanity Fair, 1901

Liberal Imperialists

Rosebery resigned as leader of the Liberal Party on 6 October 1896, to be succeeded by Harcourt and gradually moved further and further from the mainstream of the party. With the Liberals in opposition divided over the Boer War which started in 1899, Rosebery, although officially politically inactive, emerged as the head of the “Liberal Imperialists” faction of the party, opposed to Irish Home rule. He supported the war, and brought along many nonconformists likewise.[25][26] However the war was opposed by a younger faction of Liberals, including David Lloyd George and the party leader Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman.[27] Rosebery's acolytes, including H. H. Asquith and Edward Grey, regularly implored him to return as party leader and even Campbell-Bannerman said he would serve under Rosebery, if he accepted fundamental Liberal party doctrine.[28] In a much trailed speech to the Chesterfield Liberal Association in December 1901, Rosebery was widely expected to announce his return but instead delivered what Harcourt's son and private secretary Loulou described as "an insult to the whole past of the Liberal party", by telling the party to, "clean its slate".[29][30] In 1902 Rosebery was installed as president of the newly formed “Liberal League” which superseded the Liberal Imperialist League and counted amongst its vice presidents Asquith and Grey.[31]

1905 onwards

Rosebery's positions made it impossible to join the Liberal government that returned to power in 1905. Rosebery turned to writing, including biographies of Lord Chatham, Pitt the Younger, Napoleon, and Lord Randolph Churchill. Another one of his passionate interests was the collecting of rare books.

The last years of his political life saw Rosebery become a purely negative critic of the Liberal governments of Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith. His crusade "for freedom as against bureaucracy, for freedom as against democratic tyranny, for freedom as against class legislation, and ... for freedom as against Socialism"[32] was a lonely one, conducted from the crossbenches in the Lords. He joined the die-hard unionist peers in attacking Lloyd George's redistributive People's Budget in 1909 but stopped short of voting against the measure for fear of bringing retribution upon the Lords. The crisis provoked by the Lords' rejection of the budget encouraged him to reintroduce his resolutions for Lords reform, but they were lost with the dissolution of parliament in December 1910.

After assaulting the "ill-judged, revolutionary and partisan" terms of the 1911 Parliament Bill,[33] which proposed to curb the Lords' veto, he voted with the government in what proved to be his last appearance in the House of Lords. This was effectively the end of his public life, though he made several public appearances to support the war effort after 1914 and sponsored a "bantam battalion" in 1915. Though Lloyd George offered him "a high post not involving departmental labour" to augment his 1916 coalition, Rosebery declined to serve.[34]

Death and burial

Durdans, Woodcote End, Epsom, Surrey, England was the place of Rosebery's demise in 1929, shown in 2011. Its gardens are smaller than when engraved by John Hassell in 1816.

The last year of the war was clouded by two personal tragedies: his son Neil's death in Palestine in November 1917 and Rosebery's own stroke a few days before the armistice. He regained his mental powers, but his movement, hearing, and sight remained impaired for the rest of his life. His sister Constance described his last years as a "life of weariness, of total inactivity, and at the last of almost blindness". John Buchan remembered him in his last month of life, "crushed by bodily weakness" and "sunk in sad and silent meditations".[35]

Rosebery died at The Durdans, Epsom, Surrey, on 21 May 1929, to the accompaniment, as he had requested, of a gramophone recording of the "Eton Boating Song". Survived by three of his four children, he was buried in the small church at Dalmeny. By the time of his death, he was the last Victorian-era British Prime Minister alive.

His estate was probated at £1,500,122 3s. 6d.; (equivalent to £89,573,000 in 2018) and he was thus the richest prime minister ever, followed by Salisbury, then by Palmerston.[citation needed]

Marriage

Hannah de Rothschild, portrait by Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton

On 20 March 1878 in the Board of Guardians in Mount Street, London, at the age of 31 Rosebery married the 27-year-old Hannah de Rothschild (1851–1890), only child and sole heiress of the Jewish banker Mayer Amschel de Rothschild, and the wealthiest British heiress of her day. Her father had died four years previously in 1874, and bequeathed to her the bulk of his estate. Later on the same day the marriage was blessed in a Christian ceremony in Christ Church, Down Street, Piccadilly.

In January 1878 Rosebery had told a friend that he found Hannah "very simple, very unspoilt, very clever, very warm-hearted and very shy ... I never knew such a beautiful character." Both Queen Victoria's son the Prince of Wales and her cousin, the army commander George, Duke of Cambridge attended the ceremony. Hannah's death in 1890 from typhoid, compounded by Bright's disease, left him distraught.

Following his wife's death it was speculated that Rosebery intended to marry the widowed Princess Helena, Duchess of Albany, widow of Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, 4th son of Queen Victoria.[36]

It was also speculated that Rosebery was homosexual or bisexual. Like Oscar Wilde, he was hounded by John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry, for his association with Francis Douglas, Viscount Drumlanrig, one of Queensberry's sons[37] – who was his private secretary.

On 18 October 1894, sixteen months after his ennoblement, Drumlanrig died from injuries received during a shooting party. The inquest returned a verdict of "accidental death", but his death was rumoured potentially to be suicide or murder.[38] It was speculated at the time, and indeed evidence suggests,[39] that Drumlanrig may have had a romantic or sexual relationship with Rosebery. The suggestion was that Queensberry had threatened to expose the Prime Minister if his government did not vigorously prosecute Wilde for Wilde's relationship with Drumlanrig's younger brother, Lord Alfred Douglas. Queensberry believed, as he put it in a letter, that "Snob Queers like Rosebery" had corrupted his sons, and he held Rosebery indirectly responsible for Drumlanrig's death.[40]

Progeny

By his wife Hannah de Rothschild, Rosebery had two sons and two daughters, with whom, according to Margot Asquith, he loved to play:

• Albert Edward Harry Meyer Archibald Primrose, 6th Earl of Rosebery known as Harry (8 January 1882 – 30 May 1974) he married Lady Dorothy Grosvenor (granddaughter of Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster through his third son Lord Henry Grosvenor) on 15 April 1909 and was divorced from her in 1919. They had two children. He married Hon. Eva Isabel Bruce (daughter of Henry Campbell Bruce, 2nd Baron Aberdare) on 24 June 1924. They had two children.

• Neil James Archibald Primrose (14 December 1882 – 18 November 1917) he married Lady Victoria Stanley (daughter Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby) on 7 April 1915. They had one daughter: Ruth Wood, Countess of Halifax.

• Lady Sybil Primrose (1879–25 February 1955) she married General Sir Charles Grant on 28 March 1903. They had one son.

• Lady Margaret "Peggy" ,[41] Etrenne Hannah Primrose (1881–13 March 1967) she married Robert Crewe-Milnes, 1st Marquess of Crewe on 20 April 1899. They had two children.

Sporting interests

Horse racing

As a result of his marriage to Hannah de Rothschild, Rosebery acquired the Mentmore Towers estate and Mentmore stud near Leighton Buzzard which had been built by Mayer Amschel de Rothschild. Rosebery built another stable and stud near Mentmore Towers at Crafton, Buckinghamshire, called Crafton Stud.

Rosebery won several of the five English Classic Races. His most famous horses were Ladas who won the 1894 Derby, Sir Visto who did it again in 1895 (Rosebery was Prime Minister on both occasions), and Cicero in 1905.

Football

Rosebery became the first president of the London Scottish Rugby Football Club in 1878, also developed a keen interest in association football and was an early patron of the sport in Scotland. In 1882 he donated a trophy, the Rosebery Charity Cup, to be competed for by clubs under the jurisdiction of the East of Scotland Football Association. The competition lasted over 60 years and raised thousands of pounds for charities in the Edinburgh area.

Rosebery also became Honorary President of the national Scottish Football Association, with the representative Scotland national team and Honorary President of Heart of Midlothian FC. The national team occasionally forsook their traditional dark blue shirts for his traditional racing colours of primrose and pink. This occurred 9 times during Rosebery's lifetime, most notably for the 1900 British Home Championship match against England, which the Scots won 4–1. These colours were used for the away kit of the Scotland national team in 2014[42][43] and were Heart of Midlothian's away colours for season 2016/17.

Literary interests

He was a keen collector of fine books and amassed an excellent library. It was sold on 29 October 2009 at Sothebys, New Bond Street. Rosebery unveiled the statue of Robert Burns in Dumfries on 6 April 1882.[44]

Landholdings

Dalmeny House was the ancestral seat of the Earls of Rosebery and the setting for Lord and Lady Rosebery's political houseparties.

Mentmore Towers

Villa Delahente now Villa Rosebery

Rosebery was the owner of twelve houses. By marriage, he acquired:

• Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire, a huge neo-Renaissance stately home, sold in the 1970s

• Number 40, Piccadilly, in London.

With his fortune, he bought:

• a shooting lodge at Carrington in Midlothian

• a Georgian villa at Postwick in Norfolk

• In 1897, he bought Villa Delahente in Posillipo, overlooking the Bay of Naples, currently an official residence of the President of the Italian Republic, still known as Villa Rosebery

• 38 Berkeley Square, London

• The Durdans, Epsom, where he died in 1929.

As Earl of Rosebery, he was laird of:

• Dalmeny House on the banks of the Firth of Forth (pictured)

• Barnbougle Castle in the grounds of Dalmeny Estate, used by Rosebery (an insomniac) for privacy.

He rented:

• a home in Randolph Crescent, Edinburgh, during World War I

• Lansdowne House, in London, from the Marquess of Lansdowne.

Place-name tributes

The Oatlands area in the South Side of Glasgow was laid out in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, contemporary with Rosebery's most prominent period. Several of the street names have an association with him or areas around his estate to the northwest of Edinburgh: Rosebery Street, Dalmeny Street, Queensferry Street, Granton Street and Cramond Street.[45]

In London, Rosebery avenue passing through Clerkenwell was named after him, in recognition of his service as the London County Council's first chairman.[46]

Rosebery, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, is named after him. A major street, Dalmeny Avenue, runs through the area. Rosebery, Tasmania is also named after him, via the name of a mining company. Dalmeny, New South Wales, a suburb on the New South Wales South Coast, is named after him. Roseberry Avenue in the suburb of South Perth, Western Australia, is also named after him. The former township of Rosebery in South Australia (now part of Collinswood) was named for him, as was modern-day Rosebery Lane in Collinswood.[47] Rosebery in the north west of Victoria, some 15 km south of Hopetoun is also named after him.

Rosebery House, Epsom College, in Epsom, is named after him. Rosebery School sits on an area of land given to the borough by Lord Rosebery.

In October 1895 Lord Rosebery opened the new Liberal Club on Westborough, in Scarborough, only months after being Prime Minister. The building now houses a Wetherspoons, which is named in his honour.

See also

• Lady Stair's House

• In his fraudulent memoirs, Sir Edmund Backhouse, 2nd Baronet claimed to be Rosebery's lover.

References

Citations

1. Lawrence, Jon (2009). Electing Our Masters : The Hustings in British Politics from Hogarth to Blair. Oxford UP. p. 1. ISBN 9780191567766.

2. Martel, Gordon (1986). Imperial Diplomacy: Rosebery and the Failure of Foreign Policy. McGill-Queen's UP. ISBN 9780773504424.

3. Peter Stansky, Ambitions and Strategies: The Struggle for the Leadership of the Liberal Party in the 1890s (1964).

4. Robert Rhodes James, Rosebery: a biography of Archibald Philip, fifth earl of Rosebery (1963).

5. James, Robert Rhodes (1963). Rosebery (paperback 1995 ed.). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 9. ISBN 978-1857992199.

6. Rhodes James (paperback), p. 4.

7. Rhodes James (paperback), pp. 10–11.

8. Rhodes James (paperback), pp. 11–12.

9. Footprints in Time. John Colville. 1976. Chapter 2, Lord Roseberys lamb.

10. "Primrose, Rt. Hon. Archibald Philip (5th Earl of Rosebery)". The Eton Register. Part III: 1862–1868.

11. Jeyes, Samuel Henry (1906). The Earl of Rosebery. p. 5. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

12. Foster, Joseph. Alumni Oxonienses: Primrose, Archibald Philip, Baron Dalmeny. p. 1153 – via Wikisource. [scan ]

13. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rosebery, Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

14. "Papers Past – Observer – 5 May 1894 – CAP AND JACKET". Paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

15. David Brooks, "Gladstone and Midlothian: The Background to the First Campaign," Scottish Historical Review (1985) 64#1 pp. 42–67.

16. Robert Kelley, "Midlothian: A Study in Politics and Ideas," Victorian Studies (1960) 4#2, pp. 119–40.

17. Dick, David (1998). Who Was Who in Durban Street Names. Clerkington Pub. Co. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0620200349. ROSEBERY Avenue, off High Ridge Road, is named after Archibald Philip Primrose, 5"1 Earl of Rosebery who (...)

18. Turcotte, Bobbi (26 August 1982). "Former English PM's name, title still in use". Ottawa Citizen: 2. Retrieved 30 May 2016. But Primrose Avenue is named after Archibald Philip Primrose, fifth Earl of Roserbery (1847–1929), who was primse minister of England in 1894–95.

19. "Congress Presidents 1869–2002" (PDF). February 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

20. McKinstry, Leo (2006). Rosebery – Statesman in turmoil(paperback ed.). Great Britain: John Murray. pp. 265–6. ISBN 978-0719565861.

21. McKinstry (paperback), p. 159.

22. Haniamp, M. Sukru (1995). The Young Turks in Opposition. Oxford UP. pp. 61–62. ISBN 9780195358025.

23. R. C. K. Ensor. England: 1870 – 1914 (1936), pp. 238–39.

24. Gordon Martel (1986). Imperial Diplomacy: Rosebery and the Failure of Foreign Policy. McGill-Queen's UP. ISBN 9780773504424.

25. Élie Halévy, Imperialism and the Rise of Labour, 1895–1905(1951) pp. 99–110.

26. John S. Galbraith, "The pamphlet campaign on the Boer war." Journal of Modern History (1952): 111–126.

27. Wilson, John (1973). CB – A life of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1st ed.). London: Constable and Company Limited. pp. 301–2. ISBN 978-0094589506.

28. Wilson, p. 381.

29. Rhodes James (paperback), p. 433.

30. Jenkins, Roy (1964). Asquith (1994 paperback ed.). London: Pan Macmillan Publishers Limited. p. 130. ISBN 978-0333618196.

31. Wilson, p. 387.

32. The Times, 16 February 1910.

33. R. R. James, Rosebery: a biography of Archibald Philip, fifth earl of Rosebery (1963), p. 469.

34. R. O. A. Crewe-Milnes, Lord Rosebery, (1931), vol. 2. p. 51.

35. Rhodes James, p. 485.

36. Lord Rosebery to marry a Princess?, New York Times, 11 July 1901.

37. Murray, Douglas Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred DouglasISBN 0-340-76770-7

38. The Complete Peerage, Volume XIII – Peerage Creations 1901–1938. St Catherine's Press. 1949. p. 187.

39. McKenna, Neil: "The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde" (2003).

40. Lord Queensberry to Alfred Montgomery, 1 November 1894. Quoted in Murray, Douglas (2000). Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-76770-2.

41. Englefield, Dermot; Seaton, Janet; White, Isobel: Facts about the British prime ministers. A compilation of biographical and historical information. London: Mansell, 1995.

42. Brocklehurst, Steven (27 February 2014). "The beauty/horror of the garish new Scotland away strip". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

43. Ashdown, John; Freeman, Hadley (26 February 2014). "Scotland's away kit: 'A rare occasion, unknown since Beckham's glory days'". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

44. "National Burns Collection – Burns Statue, Dumfries with Tam O'Shanter…".

45. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

46. "British History Online". Retrieved 28 April 2019.

47. Rodney Cockburn, What's in Name? Nomenclature of South Australia,Ferguson, 1984.

48. J. Davis, "Primrose, Archibald Philip, fifth earl of Rosebery and first earl of Midlothian (1847–1929)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004.

49. Venn and Venn, "Dalmeny, Lord Archibald", Alumni Cantabrigenses; J. Davis, "Primrose, Archibald Philip, fifth earl of Rosebery and first earl of Midlothian (1847–1929)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004.

50. "Dalmeny, Lord Archibald", Alumni Cantabrigenses.

51. Venn and Venn, "Primrose, Archibald John (Lord Dalmeny)", Alumni Cantabrigenses; she was the first wife; Archibald Primrose, Lord Dalmeny, was born in 1809, during this marriage (see Venn and Venn, "Dalmeny, Lord Archibald", Alumni Cantabrigenses).

52. Venn and Venn, "Dalmeny, Lord Archibald", Alumni Cantabrigenses.

53. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, 1895, p. 415.

54. Venn and Venn, "Primrose, Archibald John (Lord Dalmeny)", Alumni Cantabrigenses.

55. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, 1895, p. 416; Venn and Venn, "Primrose, Archibald John (Lord Dalmeny)", Alumni Cantabrigenses.

56. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, 1895, p. 416.

57. Lodge, British Peerage, 1832, p. 353.

58. W. P. Courtney, "Stanhope, Charles", Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 54.

59. Cokayne and Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 3, 1913, p. 63.

60. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, 1895, p. 415; she was sister of the fourth Duke of Argyll and daughter of Hon. John Campbell and Elizabeth, daughter of John Elphinstone, eighth Lord Elphinstone.

61. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, p. 415.

62. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, 1895, p. 415; she was the daughter of Lt-Gen. Thomas Howard.

63. Complete Peerage, p. 416.

64. S. Farrell, "Bouverie, Hon. Bartholomew (1753–1835), of 21 Edward Street, Portman Square, Mdx.", History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1820–1832; she was the daughter of John Alleyne of Four Hills, Barbados.

65. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. 6, 1895, p. 416; Lodge, British Peerage, 1832, p. 24; he was the third son of Henry Arundell, sixth Lord Arundell.

66. Lodge, British Peerage, 1832, p. 24; she was the daughter of John Wyndham of Ashcombe, Wiltshire.

67. W. P. Courtney, "Stanhope, Charles", Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 54; she was a daughter of Charles Hamilton, Lord Binning, and sister to Thomas Hamilton, seventh Earl of Haddington.

68. W. P. Courtney, "Stanhope, Charles", Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 54; he was a younger brother of the Earl Temple.

69. Burke and Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies, 1841, pp. 34–35; M. M. Drummond, "Grenville, Henry (1717–84), of Shrub Hill, Dorking, Surr.", The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754–1790, ed. L. Namier, J. Brooke., 1964; Daughter of Sir Joseph Banks of Revesby Abbey, Lincolnshire.

70. A. F. Pollard, "Smith, Robert (1752–1838)", Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 53.

71. A. F. Pollard, "Smith, Robert (1752–1838)", Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 53; daughter of Thomas Bird of Barton, Warwickshire.

72. Cokayne and Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 3, 1913, p. 63; of Cave Castle, Yorkshire.

73. Cokayne and Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 3, 1913, p. 63; she was the daughter of William Popplewell of Monk Hill, near Pontefract.

Bibliography

• Leonard, Dick. Nineteenth-Century British Premiers: Pitt to Rosebery (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

• McKinstry, Leo. Rosebery: Statesman in Turmoil (2005) ISBN 0-7195-5879-4.

• Raymond, E. T. The Life of Lord Rosebery (1923) online

External links

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl of Rosebery

• Earl Of Rosebery 1847–1929 biography from the Liberal Democrat History Group

• More about The Earl of Roseberry on the Downing street website.

• Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rosebery, Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

• "Archival material relating to Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery". UK National Archives.

• Works by Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Portraits of Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery at the National Portrait Gallery, London

• Newspaper clippings about Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW