Charles Henry Tawney

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

Charles Henry Tawney

Born: 1837

Died: 1922

Occupation: Indologist, librarian

Charles Henry Tawney CIE (1837–1922[1][2]) was an English educator and scholar, primarily known for his translations of Sanskrit classics into English. He was fluent in German, Latin, and Greek; and in India also acquired Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu, and Persian.[3]

Biography

Tawney was the son of Rev. Richard Tawney, and educated at Rugby School and Trinity College, Cambridge; where he was a Cambridge Apostle and worked as a Fellow and Tutor for 4 years, until he moved to India for health reasons. He married Constance Catharine Fox in 1867 and had a large family.[3] One of his children, born 30 November 1880 in Calcutta, was Richard Henry or R. H. Tawney. From 1865 to his retirement in 1892 he held various educational offices, most significantly Principal of Presidency College for much of the period of 1875-1892.[3] His translation of Kathasaritsagara was printed by the Asiatic Society of Bengal in a small series called Bibliotheca Indica between 1880 and 1884.

After retirement, Tawney was made Librarian of the India Office.

Translations from Sanskrit

Tawney translated the Mālavikāgnimitra of Kālidāsa whose first edition was published in 1875 and second edition in 1891.[4]

His other works include:

• Bhavabhūti: Uttara-rāma-carita (1874) — a play

• Two Centuries of Bhartṛihari (1877) — two collections of ethical and philosophico-religious stanzas (online)

• Somadeva: Kathā Sarit Sāgara (1880-1884) — the massive collection of legends and tales (Vol I online) (Vol II online)

• Kathākoça (1895) — Jain stories (online)

• Merutunga: Prabandhacintāmaṇi (1899-1901) — Jain stories (online)

Notes

1. Thomas, F. W. (January 1923). "Charles Henry Tawney, M.A., C.I.E.". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1): 152–154. JSTOR 25210014.

2. "C. H. Tawney". Folklore. 33 (3): 334. September 30, 1922. JSTOR 1256118.

3. Penzer 1924, pp. vii-x

4. Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1902). "Bibliography of Kālidāsa's Mālavikāgnimitra and Vikramorvaçī". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 23: 93–101. doi:10.2307/592384. JSTOR 592384.

References

• Penzer, N. M. (1924), "Charles Henry Tawney", The Ocean of Story, being C.H. Tawney's Translation of Somadeva's Katha Sarit Sagara, I, London: Chas. J. Sawyer

External links

Charles Henry Tawneyat Wikipedia's sister projects

• Texts from Wikisource

• Online HTML ebook of The Ocean of Story (kathasaritsagara), volume 1-9, proofread, including thousands of notes and extra appendixes.

• Works by Charles Henry Tawney at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Charles Henry Tawney at Internet Archive

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Franz Bopp

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

Franz Bopp

Born: 14 September 1791, Mainz, Electorate of Mainz

Died: 23 October 1867 (aged 76), Berlin, Province of Brandenburg

School: Romantic linguistics[1]

Institutions: University of Berlin

Notable students: Wilhelm Dilthey

Main interests: Linguistics

Notable ideas: Comparative linguistics

Influences: Pāṇini, Friedrich Schlegel

Influenced: Max Müller; Michel Bréal; August Schleicher[2]

Franz Bopp (German: [ˈfʁants ˈbɔp]; 14 September 1791 – 23 October 1867)[a] was a German linguist known for extensive and pioneering comparative work on Indo-European languages.

Early life

Bopp was born in Mainz, but the political disarray in the Republic of Mainz caused his parents' move to Aschaffenburg, the second seat of the Archbishop of Mainz. There he received a liberal education at the Lyceum and Karl Joseph Hieronymus Windischmann drew his attention to the languages and literature of the East. (Windischmann, along with Georg Friedrich Creuzer, Joseph Görres, and the brothers Schlegel, expressed great enthusiasm for Indian wisdom and philosophy.) Moreover, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von Schlegel's book, Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (On the Speech and Wisdom of the Indians, Heidelberg, 1808), had just begun to exert a powerful influence on the minds of German philosophers and historians, and stimulated Bopp's interest in the sacred language of the Hindus.[4]

Career

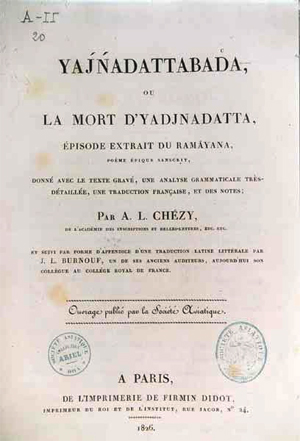

In 1812, he went to Paris at the expense of the Bavarian government, with a view to devoting himself vigorously to the study of Sanskrit. There he enjoyed the society of such eminent men as Antoine-Léonard de Chézy (his primary instructor),...

Silvestre de Sacy,...

Louis Mathieu Langlès, and, above all Alexander Hamilton (1762–1824), cousin of the American statesman of the same name, who had acquired an acquaintance with Sanskrit when in India and had brought out, along with Langlès, a descriptive catalogue of the Sanskrit manuscripts of the Imperial Library.[4]

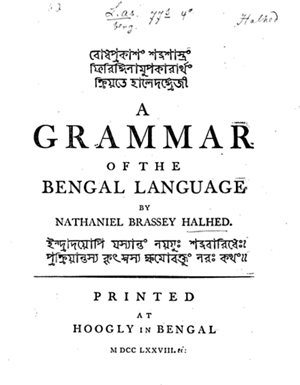

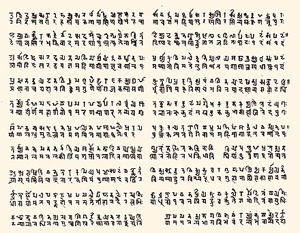

In the library, Bopp had access not only to the rich collection of Sanskrit manuscripts (mostly brought from India by Jean François Pons in the early 18th century), but also to the Sanskrit books that had been issued from the Calcutta and Serampore presses. He spent five years of laborious study, almost living in the libraries of Paris and unmoved by the turmoils that agitated the world around him, including Napoleon's escape, the Waterloo campaign and the Restoration.

The first paper from his years of study in Paris appeared in Frankfurt am Main in 1816, under the title of Über das Konjugationssystem der Sanskritsprache in Vergleichung mit jenem der griechischen, lateinischen, persischen und germanischen Sprache (On the Conjugation System of Sanskrit in comparison with that of Greek, Latin, Persian and Germanic), to which Windischmann contributed a preface. In this first book, Bopp entered at once the path on which he would focus the philological researches of his whole subsequent life. His task was not to point out the similarity of Sanskrit with Persian, Greek, Latin or German, for previous scholars had long established that, but he aimed to trace the postulated common origin of the languages' grammatical forms, of their inflections from composition. This was something no predecessor had attempted. By a historical analysis of those forms, as applied to the verb, he furnished the first trustworthy materials for a history of the languages compared.[4]

After a brief sojourn in Germany, Bopp travelled to London where he made the acquaintance of Sir Charles Wilkins and Henry Thomas Colebrooke. He also became friends with Wilhelm von Humboldt, the Prussian ambassador at the Court of St. James's, to whom he taught Sanskrit. He brought out, in the Annals of Oriental Literature (London, 1820), an essay entitled "Analytical Comparison of the Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and Teutonic Languages" in which he extended to all parts of grammar what he had done in his first book for the verb alone. He had previously published a critical edition, with a Latin translation and notes, of the story of Nala and Damayanti (London, 1819), the most beautiful episode of the Mahabharata. Other episodes of the Mahabharata, Indralokâgama, and three others (Berlin, 1824); Diluvium, and three others (Berlin, 1829); a new edition of Nala (Berlin, 1832) followed in due course, all of which, with August Wilhelm von Schlegel's edition of the Bhagavad Gita (1823), proved excellent aids in initiating the early student into the reading of Sanskrit texts. On the publication, in Calcutta, of the whole Mahabharata, Bopp discontinued editing Sanskrit texts and confined himself thenceforth exclusively to grammatical investigations.[4]

After a short residence at Göttingen, Bopp gained, on the recommendation of Humboldt, appointment to the chair of Sanskrit and comparative grammar at the University of Berlin in 1821, which he occupied for the rest of his life. He also became a member of the Royal Prussian Academy the following year.[6]

In 1827, he published his Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der Sanskritsprache (Detailed System of the Sanskrit Language), on which he had worked since 1821. Bopp started work on a new edition in Latin, for the following year, completed in 1832; a shorter grammar appeared in 1834. At the same time he compiled a Sanskrit and Latin Glossary (1830), in which, more especially in the second and third editions (1847 and 1868–71), he also took account of the cognate languages. His chief activity, however, centered on the elaboration of his Comparative Grammar, which appeared in six parts at considerable intervals (Berlin, 1833, 1835, 1842, 1847, 1849, 1852), under the title Vergleichende Grammatik des Sanskrit, Zend, Griechischen, Lateinischen, Litthauischen, Altslawischen, Gotischen und Deutschen (Comparative Grammar of Sanskrit, Zend [Avestan], Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Old Slavonic, Gothic and German).[7]

How carefully Bopp matured this work emerges from the series of monographs printed in the Transactions of the Berlin Academy (1824–1831), which preceded it.[7] They bear the general title Vergleichende Zergliederung des Sanskrits und der mit ihm verwandten Sprachen (Comparative Analysis of Sanskrit and its related Languages).[8] Two other essays (on the Numerals, 1835) followed the publication of the first part of the Comparative Grammar. Old Slavonian began to take its stand among the languages compared from the second part onwards. E. B. Eastwick translated the work into English in 1845. A second German edition, thoroughly revised (1856–1861), also covered Old Armenian.[7]

In his Comparative Grammar Bopp set himself a threefold task:

1. to give a description of the original grammatical structure of the languages as deduced from their inter-comparison.

2. to trace their phonetic laws.

3. to investigate the origin of their grammatical forms.

The first and second points remained dependent upon the third. As Bopp based his research on the best available sources and incorporated every new item of information that came to light, his work continued to widen and deepen in the making, as can be witnessed from his monographs on the vowel system in the Teutonic languages (1836), on the Celtic languages (1839), on the Old Prussian (1853) and Albanian languages (Über das Albanesische in seinen verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen, Vienna, 1854), on the accent in Sanskrit and Greek (1854), on the relationship of the Malayo-Polynesian to the Indo-European languages (1840), and on the Caucasian languages (1846). In the last two, the impetus of his genius led him on a wrong track.[7] He is the first philologist to prove Albanian as a separate branch of Indo-European.[9] Bopp was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1855.[10]

Criticism

Critics have charged Bopp with neglecting the study of the native Sanskrit grammars, but in those early days of Sanskrit studies, the great libraries of Europe did not hold the requisite materials; if they had, those materials would have demanded his full attention for years, and such grammars as those of Charles Wilkins and Henry Thomas Colebrooke, from which Bopp derived his grammatical knowledge, had all used native grammars as a basis. The further charge that Bopp, in his Comparative Grammar, gave undue prominence to Sanskrit is disproved by his own words; for, as early as 1820, he gave it as his opinion that frequently, the cognate languages serve to elucidate grammatical forms lost in Sanskrit (Annals of Or. Lit. i. 3), which he further developed in all his subsequent writings.[7]

The Encyclopædia Britannica (11th edition of 1911) assesses Bopp and his work as follows:[7]

English scholar Russell Martineau, who had studied under Bopp, gave the following tribute:[5]

Martineau also wrote:

Notes

1. Formerly sometimes anglicized as Francis Bopp[3]

References

1. Angela Esterhammer (ed.), Romantic Poetry, Volume 7, John Benjamins Publishing, 2002, p. 491.

2. Hadumod Bussmann, Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics, Routledge, 1996, p. 85.

3. Baynes 1878, p. 49.

4. Chisholm 1911, p. 240.

5. Rines 1920, p. 261.

6. Chisholm 1911, pp. 240–241.

7. Chisholm 1911, p. 241.

8. Rines 1920, p. 262.

9. Lulushi, Astrit (22 October 2013). "Histori: Çfarë ka ndodhur më 22 tetor?" [History: what happened on 22 October?] (in Albanian). New York: Dielli.

10. "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

11. Rines 1920, p. 261 cites Martineau 1867

Sources

• Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), "Francis Bopp" , Encyclopædia Britannica, 4 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 49–50

• Martineau, Russell (1867), "Obituary of Franz Bopp", Transactions of the Philological Society, London: 305–14

Attribution

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Bopp, Franz", Encyclopædia Britannica, 4 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 240–241

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920), "Bopp, Franz" , Encyclopedia Americana, 4, pp. 261–262

External links

Franz Bopp, "A Comparative Grammar, Volume 1", 1885, at the Internet Archive.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

Franz Bopp

Born: 14 September 1791, Mainz, Electorate of Mainz

Died: 23 October 1867 (aged 76), Berlin, Province of Brandenburg

School: Romantic linguistics[1]

Institutions: University of Berlin

Notable students: Wilhelm Dilthey

Main interests: Linguistics

Notable ideas: Comparative linguistics

Influences: Pāṇini, Friedrich Schlegel

Influenced: Max Müller; Michel Bréal; August Schleicher[2]

Franz Bopp (German: [ˈfʁants ˈbɔp]; 14 September 1791 – 23 October 1867)[a] was a German linguist known for extensive and pioneering comparative work on Indo-European languages.

Early life

Bopp was born in Mainz, but the political disarray in the Republic of Mainz caused his parents' move to Aschaffenburg, the second seat of the Archbishop of Mainz. There he received a liberal education at the Lyceum and Karl Joseph Hieronymus Windischmann drew his attention to the languages and literature of the East. (Windischmann, along with Georg Friedrich Creuzer, Joseph Görres, and the brothers Schlegel, expressed great enthusiasm for Indian wisdom and philosophy.) Moreover, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von Schlegel's book, Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (On the Speech and Wisdom of the Indians, Heidelberg, 1808), had just begun to exert a powerful influence on the minds of German philosophers and historians, and stimulated Bopp's interest in the sacred language of the Hindus.[4]

Career

In 1812, he went to Paris at the expense of the Bavarian government, with a view to devoting himself vigorously to the study of Sanskrit. There he enjoyed the society of such eminent men as Antoine-Léonard de Chézy (his primary instructor),...

[Antoine-Léonard de Chézy] was born at Neuilly. His father, Antoine de Chézy (1718–1798), was an engineer who finally became director of the École des Ponts et Chaussées.École des Ponts ParisTech (originally called École nationale des ponts et chaussées or ENPC, also nicknamed Ponts) is a university-level institution of higher education and research in the field of science, engineering and technology. Founded in 1747 by Daniel-Charles Trudaine, it is one of the oldest and one of the most prestigious French Grandes Écoles...

Following the creation of the Corps of Bridges and Roads in 1716, the King's Council decided in 1747 to found a specific training course for the state's engineers, as École royale des ponts et chaussées. In 1775, the school took its current name as École nationale des ponts et chaussées, by Daniel-Charles Trudaine, in a moment when the state decided to set up a progressive and efficient control of the building of roads, bridges and canals, and in the training of civil engineers.

The school's first director, from 1747 until 1794, was Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, engineer, civil service administrator and a contributor to the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. Without lecturer, fifty students (among whom Lebon, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Pierre-Simon Girard, Riche de Prony, Méchain and Brémontier), initially taught themselves geometry, algebra, mechanics and hydraulics. Visits of building sites, cooperations with scientists and engineers and participation to the drawing of the map of the kingdom used to complete their training, which was usually four to twelve years long.

During the First French Empire run by Napoleon I from 1804 to 1814, a number of members of the Corps of Bridges and Roads (including Barré de Saint-Venant, Belgrand, Biot, Cauchy, Coriolis, Dupuit, Fresnel, Gay-Lussac, Navier, Vicat) took part in the reconstruction of the French road network that had not been maintained during the Revolution, and in large infrastructural developments, notably hydraulic projects. Under the orders of the emperor, French scientist Gaspard Riche de Prony, second director of the school from 1798 to 1839, adapts the education provided by the school in order to improve the training of future civil engineers, whose purpose is to rebuild the major infrastructures of the country: roads, bridges, but also administrative buildings, barracks and fortifications. Prony is now considered as a historical and influential figure of the school. During the twenty years that followed the First Empire, the experience of the faculty and the alumni involved in the reconstruction strongly influenced its training methods and internal organisation. In 1831, the school opens its first laboratory, which aims at concentrating the talents and experiences of the country's best civil engineers. The school also gradually becomes a place of reflection and debates for urban planning.

As a new step in the evolution of the school, the decree of 1851 insists on the organisation of the courses, the writing of an annual schedule, the quality of the faculty, and the control of the students’ works. For the first time in its history, the school opens its doors to a larger public. At this time, in France, the remarkable development of transports, roads, bridges and canals is strongly influenced by engineers from the school (Becquerel, Bienvenüe, Caquot, Carnot, Colson, Coyne, Freyssinet, Résal, Séjourné), who deeply modernised the country by creating the large traffic networks, admired in several European countries.

-- École des ponts ParisTech, by Wikipedia

The son was intended for his father's profession; but in 1799 he obtained a post in the oriental manuscripts department of the national library. In about 1803, he began studying Sanskrit, and although he possessed no grammar or dictionary, he succeeded in acquiring sufficient knowledge of the language to be able to compose poetry in it.

In Paris sometime between 1800 and 1805, Friedrich Schlegel's wife Dorothea introduced him to the Wilhelmine Christiane von Klencke, called Hermina or Hermine, who, extremely unusually for the time, was a very young divorcée who had come to Paris to be a correspondent for German newspapers.Helmina von Chézy (26 January 1783 – 28 February 1856), née Wilhelmine Christiane von Klencke, was a German journalist, poet and playwright. She is known for writing the libretto for Carl Maria von Weber's opera Euryanthe (1823) and the play Rosamunde, for which Franz Schubert composed incidental music.

Helmina was born in Berlin, the daughter of Prussian officer Carl Friedrich von Klencke and his wife Caroline Louise von Klencke (1754–1802), daughter of Anna Louisa Karsch and herself a poet. The marriage of her parents had already broken up at her birth and she was partly raised by her grandmother. She started writing at the age of 14.

Married the first time in 1799, she divorced the next year and upon the death of her mother moved to Paris, where she worked as a correspondent for several German papers. From 1803 to 1807 she edited her own Französische Miszellen ("French Miscellanea") journal, commenting on political issues, which earned her trouble with the ubiquitous censors.

In Paris she befriended Friedrich Schlegel's wife Dorothea, who introduced her to the French orientalist Antoine-Léonard de Chézy. In 1805 they married and Helmina subsequently gave birth to two sons: the later author Wilhelm Theodor von Chézy (1806–1865) and Max von Chézy (1808–1846), who became a painter. In 1810, together with Adelbert von Chamisso, she translated several of Friedrich Schlegel's lectures from French into German. They had a short romantic fling, followed by another extramarital affair of Helmina with the Austrian orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, probably the father of another son who died shortly after his birth in 1811.

As her second marriage too turned out to be an unhappy one, Helmina finally parted from her husband in 1810. She returned to Germany, where she alternately lived in Heidelberg, Frankfurt, Aschaffenburg and Amorbach. In 1812 she settled in Darmstadt. She witnessed the German campaign of the Napoleonic Wars as a military hospital nurse in Cologne and Namur. After she had openly criticised the miserable conditions in the field, she was accused of libel, but was acquitted by the Berlin Kammergericht court under presiding judge E. T. A. Hoffmann.

From 1817 she lived in Dresden, where she wrote the libretto of Carl Maria von Weber's opera Euryanthe. Weber appreciated her writing but disliked her unbound ambition, speaking of her as a "suave poetess but unbearable woman". Several of her Romantic poems were set to music and Franz Schubert wrote incidental music for her play Rosamunde, which however flopped when it premiered in 1823 at the Vienna Theater an der Wien. Living in Vienna from 1823, she again became politically involved, calling attention to the inhumane working conditions at the saltworks in the Austrian Salzkammergut region. She met Beethoven who was one of her heroes growing up and became good friends with Beethoven and attended his funeral in 1827

--Helmina von Chézy, by Wikipedia

In 1805 they married and Helmina subsequently gave birth to two sons: the author Wilhelm Theodor von Chézy (1806–1865) and Max von Chézy (1808–1846), who became a painter. However, the marriage was ultimately not a success, and the couple parted, although did not divorce, in 1810. De Chézy continued to make annual payments for her support until his death.

He was the first professor of Sanskrit appointed in the Collège de France (1815), where his pupils included Alexandre Langlois, Auguste-Louis-Armand Loiseleur-Deslongchamps and especially Eugène Burnouf, who would become his successor at the Collège on his death in 1832.

He was a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur, and a member of the Académie des Inscriptions.

-- Antoine-Léonard de Chézy, by Wikipedia

Silvestre de Sacy,...

Antoine Isaac, Baron Silvestre de Sacy (French: [sasi]; 21 September 1758 – 21 February 1838), was a French nobleman, linguist and orientalist. His son, Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy, became a journalist.

Silvestre de Sacy was born in Paris to a notary named Jacques Abraham Silvestre, a Jansenist. He was born into an ardently Catholic bourgeois family...

In 1781 he was appointed councillor in the cour des monnaies, and was promoted in 1791 to be a commissary-general in the same department.The Cour des monnaies (French pronunciation: [kuʁ de mɔnɛ], Currency Court) was one of the sovereign courts of Ancien Régime France. It was set up in 1552. It and the other Ancien Régime tribunals were suppressed in 1791 after the French Revolution.

The regulation of coin-making was royal regulation par excellence and very soon became the object of strict surveillance and dedicated judicial institutions. Monetary crimes were particularly severely punished, and coin clipping and counterfeiting could be punishable by death. At first monetary justice was exercised by généraux des monnaies, but in 1346 this passed to a dedicated Chambre des monnaies, set up in 1358 at the Palais de la Cité in buildings adjoining the Chambre des comptes. Appeals against sentences passed in the Chambre des monnaies were taken to the Parlement until January 1552, when the Chambre was turned into a sovereign court called the Cour des monnaies. The pioneering historian of the French language and medieval French literature, Claude Fauchet, served as President of the Cour des monnaies from 1581-1599.

-- Cour des monnaies, by Wikipedia

Having successively studied Semitic languages, he began to make a name as an orientalist, and between 1787 and 1791 deciphered the Pahlavi inscriptions of the Sassanid kings. In 1792 he retired from public service, and lived in close seclusion in a cottage near Paris till in 1795 he became professor of Arabic in the newly founded school of living Eastern languages (École speciale des langues orientales vivantes)...

In 1806 he added the duties of Persian professor to his old chair, and from this time onwards his life was one of increasing honour and success, broken only by a brief period of retreat during the Hundred Days.

He was perpetual secretary of the Academy of Inscriptions from 1832 onwards; in 1808 he had entered the corps législatif; he was created a baron of the French Empire by Napoleon in 1813; and in 1832, when quite an old man, be became a peer of France and regularly spoke in the Chamber of Peers (Chambre des Pairs). In 1815 he became rector of the University of Paris, and after the Second Restoration he was active on the commission of public instruction. With Abel Rémusat, he was joint founder of the Société asiatique, and was inspector of oriental typefaces at the Imprimerie nationale. In 1821 he was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.

Silvestre de Sacy was the first Frenchman to attempt to read the Rosetta stone. He made some progress in identifying proper names in the demotic inscription.

From 1807 to 1809, Sacy was also a teacher of Jean-François Champollion, whom he encouraged in his research.

But later on, the relationship between the master and student became chilly. In no small measure, Champollion's Napoleonic sympathies were problematic for Sacy, who was decidedly Royalist in his political sympathies.

-- Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy, by Wikipedia

Louis Mathieu Langlès, and, above all Alexander Hamilton (1762–1824), cousin of the American statesman of the same name, who had acquired an acquaintance with Sanskrit when in India and had brought out, along with Langlès, a descriptive catalogue of the Sanskrit manuscripts of the Imperial Library.[4]

In the library, Bopp had access not only to the rich collection of Sanskrit manuscripts (mostly brought from India by Jean François Pons in the early 18th century), but also to the Sanskrit books that had been issued from the Calcutta and Serampore presses. He spent five years of laborious study, almost living in the libraries of Paris and unmoved by the turmoils that agitated the world around him, including Napoleon's escape, the Waterloo campaign and the Restoration.

The first paper from his years of study in Paris appeared in Frankfurt am Main in 1816, under the title of Über das Konjugationssystem der Sanskritsprache in Vergleichung mit jenem der griechischen, lateinischen, persischen und germanischen Sprache (On the Conjugation System of Sanskrit in comparison with that of Greek, Latin, Persian and Germanic), to which Windischmann contributed a preface. In this first book, Bopp entered at once the path on which he would focus the philological researches of his whole subsequent life. His task was not to point out the similarity of Sanskrit with Persian, Greek, Latin or German, for previous scholars had long established that, but he aimed to trace the postulated common origin of the languages' grammatical forms, of their inflections from composition. This was something no predecessor had attempted. By a historical analysis of those forms, as applied to the verb, he furnished the first trustworthy materials for a history of the languages compared.[4]

After a brief sojourn in Germany, Bopp travelled to London where he made the acquaintance of Sir Charles Wilkins and Henry Thomas Colebrooke. He also became friends with Wilhelm von Humboldt, the Prussian ambassador at the Court of St. James's, to whom he taught Sanskrit. He brought out, in the Annals of Oriental Literature (London, 1820), an essay entitled "Analytical Comparison of the Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and Teutonic Languages" in which he extended to all parts of grammar what he had done in his first book for the verb alone. He had previously published a critical edition, with a Latin translation and notes, of the story of Nala and Damayanti (London, 1819), the most beautiful episode of the Mahabharata. Other episodes of the Mahabharata, Indralokâgama, and three others (Berlin, 1824); Diluvium, and three others (Berlin, 1829); a new edition of Nala (Berlin, 1832) followed in due course, all of which, with August Wilhelm von Schlegel's edition of the Bhagavad Gita (1823), proved excellent aids in initiating the early student into the reading of Sanskrit texts. On the publication, in Calcutta, of the whole Mahabharata, Bopp discontinued editing Sanskrit texts and confined himself thenceforth exclusively to grammatical investigations.[4]

After a short residence at Göttingen, Bopp gained, on the recommendation of Humboldt, appointment to the chair of Sanskrit and comparative grammar at the University of Berlin in 1821, which he occupied for the rest of his life. He also became a member of the Royal Prussian Academy the following year.[6]

In 1827, he published his Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der Sanskritsprache (Detailed System of the Sanskrit Language), on which he had worked since 1821. Bopp started work on a new edition in Latin, for the following year, completed in 1832; a shorter grammar appeared in 1834. At the same time he compiled a Sanskrit and Latin Glossary (1830), in which, more especially in the second and third editions (1847 and 1868–71), he also took account of the cognate languages. His chief activity, however, centered on the elaboration of his Comparative Grammar, which appeared in six parts at considerable intervals (Berlin, 1833, 1835, 1842, 1847, 1849, 1852), under the title Vergleichende Grammatik des Sanskrit, Zend, Griechischen, Lateinischen, Litthauischen, Altslawischen, Gotischen und Deutschen (Comparative Grammar of Sanskrit, Zend [Avestan], Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Old Slavonic, Gothic and German).[7]

How carefully Bopp matured this work emerges from the series of monographs printed in the Transactions of the Berlin Academy (1824–1831), which preceded it.[7] They bear the general title Vergleichende Zergliederung des Sanskrits und der mit ihm verwandten Sprachen (Comparative Analysis of Sanskrit and its related Languages).[8] Two other essays (on the Numerals, 1835) followed the publication of the first part of the Comparative Grammar. Old Slavonian began to take its stand among the languages compared from the second part onwards. E. B. Eastwick translated the work into English in 1845. A second German edition, thoroughly revised (1856–1861), also covered Old Armenian.[7]

In his Comparative Grammar Bopp set himself a threefold task:

1. to give a description of the original grammatical structure of the languages as deduced from their inter-comparison.

2. to trace their phonetic laws.

3. to investigate the origin of their grammatical forms.

The first and second points remained dependent upon the third. As Bopp based his research on the best available sources and incorporated every new item of information that came to light, his work continued to widen and deepen in the making, as can be witnessed from his monographs on the vowel system in the Teutonic languages (1836), on the Celtic languages (1839), on the Old Prussian (1853) and Albanian languages (Über das Albanesische in seinen verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen, Vienna, 1854), on the accent in Sanskrit and Greek (1854), on the relationship of the Malayo-Polynesian to the Indo-European languages (1840), and on the Caucasian languages (1846). In the last two, the impetus of his genius led him on a wrong track.[7] He is the first philologist to prove Albanian as a separate branch of Indo-European.[9] Bopp was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1855.[10]

Criticism

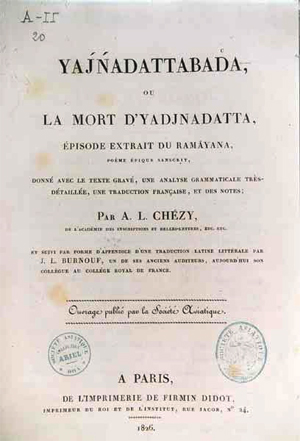

Critics have charged Bopp with neglecting the study of the native Sanskrit grammars, but in those early days of Sanskrit studies, the great libraries of Europe did not hold the requisite materials; if they had, those materials would have demanded his full attention for years, and such grammars as those of Charles Wilkins and Henry Thomas Colebrooke, from which Bopp derived his grammatical knowledge, had all used native grammars as a basis. The further charge that Bopp, in his Comparative Grammar, gave undue prominence to Sanskrit is disproved by his own words; for, as early as 1820, he gave it as his opinion that frequently, the cognate languages serve to elucidate grammatical forms lost in Sanskrit (Annals of Or. Lit. i. 3), which he further developed in all his subsequent writings.[7]

The Encyclopædia Britannica (11th edition of 1911) assesses Bopp and his work as follows:[7]

Bopp's researches, carried with wonderful penetration into the most minute and almost microscopical details of linguistic phenomena, have led to the opening up of a wide and distant view into the original seats, the closer or more distant affinity, and the tenets, practices and domestic usages of the ancient Indo-European nations, and the science of comparative grammar may truly be said to date from his earliest publication. In grateful recognition of that fact, on the fiftieth anniversary (May 16, 1866) of the date of Windischmann's preface to that work, a fund called Die Bopp-Stiftung, for the promotion of the study of Sanskrit and comparative grammar, was established at Berlin, to which liberal contributions were made by his numerous pupils and admirers in all parts of the globe. Bopp lived to see the results of his labours everywhere accepted, and his name justly celebrated. But he died, on the 23rd of October 1867, in poverty, though his genuine kindliness and unselfishness, his devotion to his family and friends, and his rare modesty, endeared him to all who knew him.[7]

English scholar Russell Martineau, who had studied under Bopp, gave the following tribute:[5]

Bopp must, more or less, directly or indirectly, be the teacher of all who at the present day study, not this language or that language, but language itself — study it either as a universal function of man, subjected, like his other mental or physical functions, to law and order, or else as an historical development, worked out by a never ceasing course of education from one form into another.[11]

Martineau also wrote:

"Bopp's Sanskrit studies and Sanskrit publications are the solid foundations upon which his system of comparative grammar was erected, and without which that could not have been perfect. For that purpose, far more than a mere dictionary knowledge of Sanskrit was required. The resemblances which he detected between Sanskrit and the Western cognate tongues existed in the syntax, the combination of words in the sentence and the various devices which only actual reading of the literature could disclose, far more than in the mere vocabulary. As a comparative grammarian he was much more than as a Sanskrit scholar, ... [and yet] it is surely much that he made the grammar, formerly a maze of Indian subtilty, as simple and attractive as that of Greek or Latin, introduced the study of the easier works of Sanskrit literature and trained (personally or by his books) pupils who could advance far higher, invade even the most intricate parts of the literature and make the Vedas intelligible. The great truth which his Comparative Grammar established was that of the mutual relations of the connected languages. Affinities had before him been observed between Latin and German, between German and Slavonic, etc., yet all attempts to prove one the parent of the other had been found preposterous.[11]

Notes

1. Formerly sometimes anglicized as Francis Bopp[3]

References

1. Angela Esterhammer (ed.), Romantic Poetry, Volume 7, John Benjamins Publishing, 2002, p. 491.

2. Hadumod Bussmann, Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics, Routledge, 1996, p. 85.

3. Baynes 1878, p. 49.

4. Chisholm 1911, p. 240.

5. Rines 1920, p. 261.

6. Chisholm 1911, pp. 240–241.

7. Chisholm 1911, p. 241.

8. Rines 1920, p. 262.

9. Lulushi, Astrit (22 October 2013). "Histori: Çfarë ka ndodhur më 22 tetor?" [History: what happened on 22 October?] (in Albanian). New York: Dielli.

10. "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

11. Rines 1920, p. 261 cites Martineau 1867

Sources

• Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), "Francis Bopp" , Encyclopædia Britannica, 4 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 49–50

• Martineau, Russell (1867), "Obituary of Franz Bopp", Transactions of the Philological Society, London: 305–14

Attribution

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Bopp, Franz", Encyclopædia Britannica, 4 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 240–241

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920), "Bopp, Franz" , Encyclopedia Americana, 4, pp. 261–262

External links

Franz Bopp, "A Comparative Grammar, Volume 1", 1885, at the Internet Archive.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36135

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Friedrich Schlegel

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

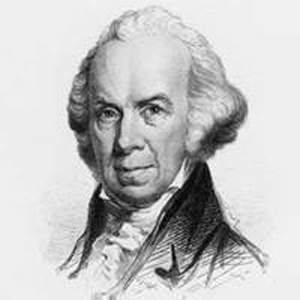

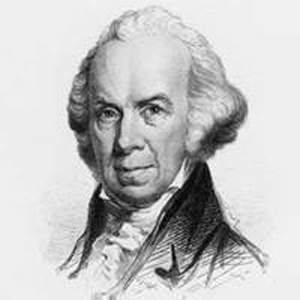

Friedrich Schlegel

Friedrich Schlegel in 1801

Born: 10 March 1772, Hanover, Electorate of Hanover

Died: 12 January 1829 (aged 56), Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony

Alma mater: University of Göttingen; University of Leipzig

Era: 19th-century philosophy

Region: Western philosophy

School: Jena Romanticism; German idealism[1]; Epistemic coherentism[2]; Coherence theory of truth[3]; Historicism[4]; Romantic linguistics[5]; Republicanism (before 1808); Conservatism (after 1808)

Main interests: Epistemology, philology, philosophy of history

Notable ideas: Grounding epistemology on reciprocal proof (Wechselerweis), not original principle (Grundsatz)[6][2]; Coining the term "historicism", (Historismus)[4]; Out of India theory

Influences: Immanuel Kant, J. G. Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder[7]

Influenced: Franz Bopp

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel (/ˈʃleɪɡəl/;[8] German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʃleːgl̩];[8][9][10] 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Romanticism.

Born into a fervently Protestant family, Schlegel rejected Christianity as a young man in favor of atheism and individualism. He entered university to study law but instead focused on classical literature. He began a career as a writer and lecturer, and founded journals such as Athenaeum. In 1808 Schlegel converted to Catholicism. His religious conversion ultimately led to his estrangement from family and old friends. He moved to Austria in 1809, where he became a diplomat and journalist in service of Klemens von Metternich, the Foreign Minister of the Austrian Empire. Schlegel died in 1829, at the age of 56.[11]

Schlegel was a promoter of the Romantic movement and inspired Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Adam Mickiewicz and Kazimierz Brodziński. The first to notice what became known as Grimm's law, Schlegel was a pioneer in Indo-European studies, comparative linguistics, and morphological typology, publishing in 1819 the first theory linking the Indo-Iranian and German languages under the Aryan group.[12][13]

Life and work

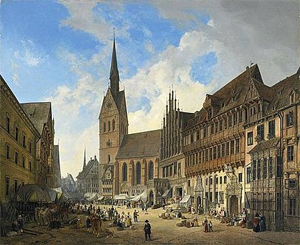

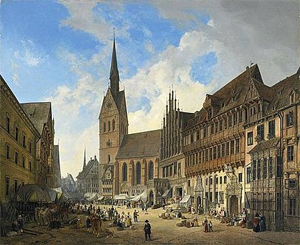

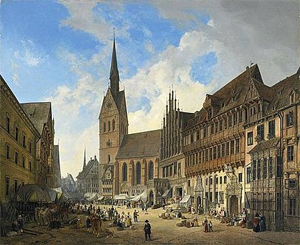

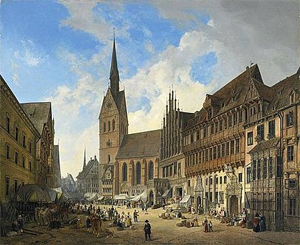

Hanover's Market Church

Oil painting after Domenico Quaglio (1832)

Karl Friedrich von Schlegel was born on 10 March 1772 at Hanover, where his father, Johann Adolf Schlegel, was the pastor at the Lutheran Market Church. For two years he studied law at Göttingen and Leipzig, and he met with Friedrich Schiller. In 1793 he devoted himself entirely to literary work. In 1796 he moved to Jena, where his brother August Wilhelm lived, and here he collaborated with Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Fichte, and Caroline Schelling, who married August Wilhelm. Novalis and Schlegel had a famous conversation about German idealism. In 1797 he quarreled with Schiller, who did not like his polemic work.[14]

Schlegel published Die Griechen und Römer (The Greeks and Romans), which was followed by Geschichte der Poesie der Griechen und Römer (History of the Poesy of the Greeks and Romans) (1798). Then he turned to Dante, Goethe, and Shakespeare. In Jena he and his brother founded the journal Athenaeum, contributing fragments, aphorisms, and essays in which the principles of the Romantic school are most definitely stated. They are now generally recognized as the deepest and most significant expressions of the subjective idealism of the early Romanticists.[15] After a controversy, Friedrich decided to move to Berlin. There he lived with Friedrich Schleiermacher and met Henriette Herz, Rahel Varnhagen, and his future wife, Dorothea Veit, a daughter of Moses Mendelssohn and the mother of Johannes and Philipp Veit.[11] In 1799 he published Lucinde, an eccentric and unfinished novel, which is remarkable as an attempt to transfer to practical ethics the Romantic demand for complete individual freedom.[16] Lucinde, in which he extolled the union of sensual and spiritual love as an allegory of the divine cosmic Eros, caused a great scandal by its manifest autobiographical character, mirroring his liaison with Dorothea Veit, and it contributed to the failure of his academic career in Jena [15] where he completed his studies in 1801 and lectured as a Privatdozent on transcendental philosophy. In September 1800 he met four times with Goethe, who would later stage his tragedy Alarcos (1802) in Weimar, albeit with a notable lack of success.

In June 1802 he arrived in Paris, where he lived in the house formerly owned by Baron d'Holbach and joined a circle including Heinrich Christoph Kolbe. He lectured on philosophy in private courses for Sulpiz Boisserée, and under the tutelage of Antoine-Léonard de Chézy and linguist Alexander Hamilton he continued to study Sanskrit and the Persian language. He edited the journal Europa (1803), where he published essays about Gothic architecture and the Old Masters. In April 1804 he married Dorothea Veit in the Swedish embassy in Paris, after she had undergone the requisite conversion from Judaism to Protestantism. In 1806 he and his wife went to visit Aubergenville, where his brother lived with Madame de Staël.

In 1808 he published an epoch-making book, Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (On the Language and Wisdom of India). Here he advanced his ideas about religion and importantly argued that a people originating from India were the founders of the first European civilizations. Schlegel compared Sanskrit with Latin, Greek, Persian and German, noting many similarities in vocabulary and grammar. The assertion of the common features of these languages is now generally accepted, albeit with significant revisions. There is less agreement about the geographic region where these precursors settled, although the Out-of-India model has generally become discredited.

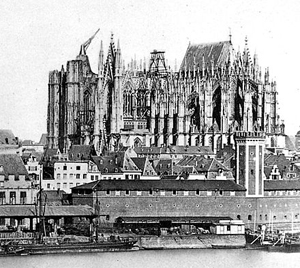

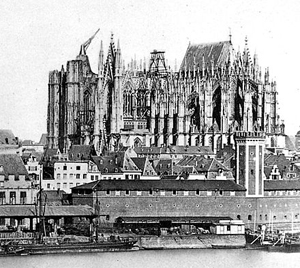

The unfinished Cologne cathedral (1856) with medieval crane on the south tower

In 1808, he and his wife joined the Roman Catholic Church in the Cologne Cathedral. From this time on, he became more and more opposed to the principles of political and religious freedom. He went to Vienna and in 1809 was appointed imperial court secretary at the military headquarters, editing the army newspaper and issuing fiery proclamations against Napoleon. He accompanied archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen to war and was stationed in Pest during the War of the Fifth Coalition. Here he studied the Hungarian language. Meanwhile he had published his collected Geschichte (Histories) (1809) and two series of lectures, Über die neuere Geschichte (On Recent History) (1811) and Geschichte der alten und neuen Literatur (On Old and New Literature) (1815). In 1814 he was knighted in the Supreme Order of Christ.

Schlegel's grave at the Old Catholic Cemetery, Dresden

Following the Congress of Vienna (1815), he was councilor of legation in the Austrian embassy at the Frankfurt Diet, but in 1818 he returned to Vienna. In 1819 he and Clemens Brentano made a trip to Rome, in the company of Metternich and Gentz. There he met with his wife and her sons. In 1820 he started a conservative Catholic magazine, Concordia (1820–1823), but was criticized by Metternich and by his brother August Wilhelm, then professor of Indology in Bonn and busy publishing the Bhagavad Gita. Schlegel began the issue of his Sämtliche Werke (Collected Works). He also delivered lectures, which were republished in his Philosophie des Lebens (Philosophy of Life) (1828) and in his Philosophie der Geschichte (Philosophy of History) (1829). He died on 12 January 1829 at Dresden, while preparing a series of lectures.

Dorothea von Schlegel (1790) by Anton Graff

Dorothea Schlegel

Friedrich Schlegel's wife, Dorothea von Schlegel, authored an unfinished romance, Florentin (1802), a Sammlung romantischer Dichtungen des Mittelalters (Collection of Romantic Poems of the Middle Ages) (2 vols., 1804), a version of Lother und Maller (1805), and a translation of Madame de Staël's Corinne (1807–1808) — all of which were issued under her husband's name. By her first marriage she had two sons, Johannes and Philipp Veit, who became eminent Catholic painters.

Selected works

• Vom ästhetischen Werte der griechischen Komödie (1794)

• Über die Diotima (1795)

• Versuch über den Begriff des Republikanismus (1796)

• Georg Forster (1797)

• Über das Studium der griechischen Poesie (1797)

• Über Lessing (1797)

• Kritische Fragmente („Lyceums“-Fragmente) (1797)

• Fragmente („Athenaeums“-Fragmente) (1797–1798)

• Lucinde (1799)

• Über die Philosophie. An Dorothea (1799)

• Gespräch über die Poesie (1800)

• Über die Unverständlichkeit (1800)

• Ideen (1800)

• Charakteristiken und Kritiken (1801)

• Transcendentalphilosophie (1801)

• Alarkos (1802)

• Reise nach Frankreich (1803

• Geschichte der europäischen Literatur (1803/1804

• Grundzüge der gotischen Baukunst (1804/1805)

• Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (1808)

• Deutsches Museum (as ed.), 4 Vols. Vienna (1812–1813)

• Geschichte der alten und neueren Literatur (lectures) (1815)

Letters

• Ludwig Tieck und die Brüder Schlegel. Briefe ed. by Edgar Lohner (München 1972)

Friedrich Schlegel's Sämtliche Werke appeared in 10 vols. (1822–1825); a second edition (1846) in 55 vols. His Prosaische Jugendschriften (1794–1802) have been edited by J. Minor (1882, 2nd ed. 1906); there are also reprints of Lucinde, and F. Schleiermacher's Vertraute Briefe über Lucinde, 1800 (1907). See R. Haym, Die romantische Schule (1870); I. Rouge, F. Schlegel et la genie du romantisme allemand (1904); by the same, Erläuterungen zu F. Schlegels „Lucinde“ (1905); M. Joachimi, Die Weltanschauung der Romantik (1905); W. Glawe, Die Religion F. Schlegels (1906); E. Kircher, Philosophie der Romantik (1906); M. Frank "Unendliche Annäherung". Die Anfänge der philosophischen Frühromantik (1997); Andrew Bowie, From Romanticism to Critical Theory: The Philosophy of German Literary Theory (1997).

Notes

1. Frederick C. Beiser, German Idealism: The Struggle Against Subjectivism, 1781–1801, Harvard University Press, 2002, p. 349.

2. Asko Nivala, The Romantic Idea of the Golden Age in Friedrich Schlegel's Philosophy of History, Routledge, 2017, p. 23.

3. Elizabeth Millan, Friedrich Schlegel and the Emergence of Romantic Philosophy, SUNY Press, 2012, p. 49.

4. Brian Leiter, Michael Rosen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Continental Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 175: "[The word 'historicism'] appears as early as the late eighteenth century in the writings of the German romantics, who used it in a neutral sense. In 1797 Friedrich Schlegel used 'historicism' to refer to a philosophy that stresses the importance of history ..."; Katherine Harloe, Neville Morley (eds.), Thucydides and the Modern World: Reception, Reinterpretation and Influence from the Renaissance to the Present, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 81: "Already in Friedrich Schlegel's Fragments about Poetry and Literature (a collection of notes attributed to 1797), the word Historismusoccurs five times."

5. Angela Esterhammer (ed.), Romantic Poetry, Volume 7, John Benjamins Publishing, 2002, p. 491.

6. Michael N. Forster, Kristin Gjesdal (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of German Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 81.

7. Michael N. Forster, After Herder: Philosophy of Language in the German Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 9.

8. Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

9. "Friedrich – Französisch-Übersetzung – Langenscheidt Deutsch-Französisch Wörterbuch" (in German and French). Langenscheidt. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

10. "Duden | Schlegel | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition". Duden (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2018.

11. Speight (, Allen 2007). "Friedrich Schlegel". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy..

12. Watkins, Calvert (2000), "Aryan", American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.), New York: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-82517-2, ...when Friedrich Schlegel, a German scholar who was an important early Indo-Europeanist, came up with a theory that linked the Indo-Iranian words with the German word Ehre, 'honor', and older Germanic names containing the element ario-, such as the Swiss [sic] warrior Ariovistus who was written about by Julius Caesar. Schlegel theorized that far from being just a designation of the Indo-Iranians, the word *arya- had in fact been what the Indo-Europeans called themselves, meaning [according to Schlegel] something like 'the honorable people.' (This theory has since been called into question.)

13. Schlegel, Friedrich. 1819. Review of J. G. Rhode, Über den Anfang unserer Geschichte und die letzte Revolution der Erde, Breslau, 1819. Jahrbücher der Literatur VIII: 413ff

14. Ernst Behler, German Romantic Literary Theory, 1993, p. 36.

15. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Böhme, Traugott (1920). "Schlegel, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von" . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

16. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Schlegel, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

17. Adam Zamoyski (2007), Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna, pp. 242–243.

Further reading

• Berman, Antoine. L'épreuve de l'étranger. Culture et traduction dans l'Allemagne romantique: Herder, Goethe, Schlegel, Novalis, Humboldt, Schleiermacher, Hölderlin., Paris, Gallimard, Essais, 1984. ISBN 978-2-07-070076-9

• Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, The Literary Absolute: The Theory of Literature in German Romanticism, Albany: State University Press of New York, 1988. [A philosophical exegesis of early romantic theory focused on F. Schlegel, Novalis, and the Athenaeum.]

External links

• Works by Friedrich Schlegel at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Friedrich Schlegel at Internet Archive

• Works by Friedrich Schlegel at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Dictionary of Art

• "Schlegel, Friedrich von" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

• "Schlegel, Friedrich von" . The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

• "Friedrich von Schlegel" . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

• "Schlegel, Friedrich von" . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

• Works by Friedrich Schlegel at Projekt Gutenberg-DE (in German)

• "Works by Friedrich Schlegel". Zeno.org (in German).

• Franz Muncker (1891), "Schlegel, Friedrich von", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 33, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 737–752

• "Friedrich Schlegel". Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German).

• Literature by and about Friedrich Schlegel in the German National Library catalogue

• Schlegel, Friedrich von, 1841 "Lectures on the History of Literature, Ancient and Modern". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Schlegel, Friedrich von, 1772–1829; Robertson, James Burton, 1800–1877, 1846 "The philosophy of history : in a course of lectures, delivered at Vienna". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Schiller, Friedrich, 1759–1805; Körner, Christian Gottfried, 1756–1831; Simpson, Leonard Francis, translated 1849 "Correspondence of Schiller with Körner. Comprising sketches and anecdotes of Goethe, the Schlegels, Wielands, and other contemporaries". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Schlegel, Friedrich von, 1855 "The philosophy of life, and Philosophy of language, in a course of lectures". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Friedrich von Schlegel, Ellen J . Millington, 1860 "The Aesthetic and Miscellaneous Works of Friedrich Von Schlegel". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Samuel Paul Capen, 1903 "Friedrich Schlegel's Relations with Reichardt and His Contributions to "Deutschland"". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Wilson, Augusta Manie, 1908 "The principle of the ego in philosophy with special reference to its influence upon Schlegel's doctrine of "ironie"". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Calvin Thomas, 1913 "Friedrich Schlegel, Introduction to Lucinda". Retrieved 2010-09-28.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

-- Aphorisms, by Friedrich Schlegel

-- Lucinda, by Friedrich Schlegel

-- Works of Frederick von Schlegel: Comprising (1) Letters on Christian Art; (2) An Essay on Gothic Architecture; (3) Remarks on the Romance-Poetry of the Middle Ages and on Shakspere; (4) On the Limits of the Beautiful; and (5) On the Language and Wisdom of the Indians, by Frederick von Schlegel, Translated from the German by E.J. Millngton

Friedrich Schlegel

Friedrich Schlegel in 1801

Born: 10 March 1772, Hanover, Electorate of Hanover

Died: 12 January 1829 (aged 56), Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony

Alma mater: University of Göttingen; University of Leipzig

Era: 19th-century philosophy

Region: Western philosophy

School: Jena Romanticism; German idealism[1]; Epistemic coherentism[2]; Coherence theory of truth[3]; Historicism[4]; Romantic linguistics[5]; Republicanism (before 1808); Conservatism (after 1808)

Main interests: Epistemology, philology, philosophy of history

Notable ideas: Grounding epistemology on reciprocal proof (Wechselerweis), not original principle (Grundsatz)[6][2]; Coining the term "historicism", (Historismus)[4]; Out of India theory

Influences: Immanuel Kant, J. G. Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder[7]

Influenced: Franz Bopp

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel (/ˈʃleɪɡəl/;[8] German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʃleːgl̩];[8][9][10] 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Romanticism.

Born into a fervently Protestant family, Schlegel rejected Christianity as a young man in favor of atheism and individualism. He entered university to study law but instead focused on classical literature. He began a career as a writer and lecturer, and founded journals such as Athenaeum. In 1808 Schlegel converted to Catholicism. His religious conversion ultimately led to his estrangement from family and old friends. He moved to Austria in 1809, where he became a diplomat and journalist in service of Klemens von Metternich, the Foreign Minister of the Austrian Empire. Schlegel died in 1829, at the age of 56.[11]

Schlegel was a promoter of the Romantic movement and inspired Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Adam Mickiewicz and Kazimierz Brodziński. The first to notice what became known as Grimm's law, Schlegel was a pioneer in Indo-European studies, comparative linguistics, and morphological typology, publishing in 1819 the first theory linking the Indo-Iranian and German languages under the Aryan group.[12][13]

Life and work

Hanover's Market Church

Oil painting after Domenico Quaglio (1832)

Karl Friedrich von Schlegel was born on 10 March 1772 at Hanover, where his father, Johann Adolf Schlegel, was the pastor at the Lutheran Market Church. For two years he studied law at Göttingen and Leipzig, and he met with Friedrich Schiller. In 1793 he devoted himself entirely to literary work. In 1796 he moved to Jena, where his brother August Wilhelm lived, and here he collaborated with Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Fichte, and Caroline Schelling, who married August Wilhelm. Novalis and Schlegel had a famous conversation about German idealism. In 1797 he quarreled with Schiller, who did not like his polemic work.[14]

Schlegel published Die Griechen und Römer (The Greeks and Romans), which was followed by Geschichte der Poesie der Griechen und Römer (History of the Poesy of the Greeks and Romans) (1798). Then he turned to Dante, Goethe, and Shakespeare. In Jena he and his brother founded the journal Athenaeum, contributing fragments, aphorisms, and essays in which the principles of the Romantic school are most definitely stated. They are now generally recognized as the deepest and most significant expressions of the subjective idealism of the early Romanticists.[15] After a controversy, Friedrich decided to move to Berlin. There he lived with Friedrich Schleiermacher and met Henriette Herz, Rahel Varnhagen, and his future wife, Dorothea Veit, a daughter of Moses Mendelssohn and the mother of Johannes and Philipp Veit.[11] In 1799 he published Lucinde, an eccentric and unfinished novel, which is remarkable as an attempt to transfer to practical ethics the Romantic demand for complete individual freedom.[16] Lucinde, in which he extolled the union of sensual and spiritual love as an allegory of the divine cosmic Eros, caused a great scandal by its manifest autobiographical character, mirroring his liaison with Dorothea Veit, and it contributed to the failure of his academic career in Jena [15] where he completed his studies in 1801 and lectured as a Privatdozent on transcendental philosophy. In September 1800 he met four times with Goethe, who would later stage his tragedy Alarcos (1802) in Weimar, albeit with a notable lack of success.

In June 1802 he arrived in Paris, where he lived in the house formerly owned by Baron d'Holbach and joined a circle including Heinrich Christoph Kolbe. He lectured on philosophy in private courses for Sulpiz Boisserée, and under the tutelage of Antoine-Léonard de Chézy and linguist Alexander Hamilton he continued to study Sanskrit and the Persian language. He edited the journal Europa (1803), where he published essays about Gothic architecture and the Old Masters. In April 1804 he married Dorothea Veit in the Swedish embassy in Paris, after she had undergone the requisite conversion from Judaism to Protestantism. In 1806 he and his wife went to visit Aubergenville, where his brother lived with Madame de Staël.

In 1808 he published an epoch-making book, Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (On the Language and Wisdom of India). Here he advanced his ideas about religion and importantly argued that a people originating from India were the founders of the first European civilizations. Schlegel compared Sanskrit with Latin, Greek, Persian and German, noting many similarities in vocabulary and grammar. The assertion of the common features of these languages is now generally accepted, albeit with significant revisions. There is less agreement about the geographic region where these precursors settled, although the Out-of-India model has generally become discredited.

The unfinished Cologne cathedral (1856) with medieval crane on the south tower

In 1808, he and his wife joined the Roman Catholic Church in the Cologne Cathedral. From this time on, he became more and more opposed to the principles of political and religious freedom. He went to Vienna and in 1809 was appointed imperial court secretary at the military headquarters, editing the army newspaper and issuing fiery proclamations against Napoleon. He accompanied archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen to war and was stationed in Pest during the War of the Fifth Coalition. Here he studied the Hungarian language. Meanwhile he had published his collected Geschichte (Histories) (1809) and two series of lectures, Über die neuere Geschichte (On Recent History) (1811) and Geschichte der alten und neuen Literatur (On Old and New Literature) (1815). In 1814 he was knighted in the Supreme Order of Christ.

Schlegel's grave at the Old Catholic Cemetery, Dresden

In collaboration with Josef von Pilat, editor of the Österreichischer Beobachter, and with the help of Adam Müller and Friedrich Schlegel, Metternich and Gentz projected a vision of Austria as the spiritual leader of a new Germany, drawing her strength and inspiration from a romanticised view of a medieval Catholic past.[17]

Following the Congress of Vienna (1815), he was councilor of legation in the Austrian embassy at the Frankfurt Diet, but in 1818 he returned to Vienna. In 1819 he and Clemens Brentano made a trip to Rome, in the company of Metternich and Gentz. There he met with his wife and her sons. In 1820 he started a conservative Catholic magazine, Concordia (1820–1823), but was criticized by Metternich and by his brother August Wilhelm, then professor of Indology in Bonn and busy publishing the Bhagavad Gita. Schlegel began the issue of his Sämtliche Werke (Collected Works). He also delivered lectures, which were republished in his Philosophie des Lebens (Philosophy of Life) (1828) and in his Philosophie der Geschichte (Philosophy of History) (1829). He died on 12 January 1829 at Dresden, while preparing a series of lectures.

Dorothea von Schlegel (1790) by Anton Graff

Dorothea Schlegel

Friedrich Schlegel's wife, Dorothea von Schlegel, authored an unfinished romance, Florentin (1802), a Sammlung romantischer Dichtungen des Mittelalters (Collection of Romantic Poems of the Middle Ages) (2 vols., 1804), a version of Lother und Maller (1805), and a translation of Madame de Staël's Corinne (1807–1808) — all of which were issued under her husband's name. By her first marriage she had two sons, Johannes and Philipp Veit, who became eminent Catholic painters.

Selected works

• Vom ästhetischen Werte der griechischen Komödie (1794)

• Über die Diotima (1795)

• Versuch über den Begriff des Republikanismus (1796)

• Georg Forster (1797)

• Über das Studium der griechischen Poesie (1797)

• Über Lessing (1797)

• Kritische Fragmente („Lyceums“-Fragmente) (1797)

• Fragmente („Athenaeums“-Fragmente) (1797–1798)

• Lucinde (1799)

• Über die Philosophie. An Dorothea (1799)

• Gespräch über die Poesie (1800)

• Über die Unverständlichkeit (1800)

• Ideen (1800)

• Charakteristiken und Kritiken (1801)

• Transcendentalphilosophie (1801)

• Alarkos (1802)

• Reise nach Frankreich (1803

• Geschichte der europäischen Literatur (1803/1804

• Grundzüge der gotischen Baukunst (1804/1805)

• Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (1808)

• Deutsches Museum (as ed.), 4 Vols. Vienna (1812–1813)

• Geschichte der alten und neueren Literatur (lectures) (1815)

Letters

• Ludwig Tieck und die Brüder Schlegel. Briefe ed. by Edgar Lohner (München 1972)

Friedrich Schlegel's Sämtliche Werke appeared in 10 vols. (1822–1825); a second edition (1846) in 55 vols. His Prosaische Jugendschriften (1794–1802) have been edited by J. Minor (1882, 2nd ed. 1906); there are also reprints of Lucinde, and F. Schleiermacher's Vertraute Briefe über Lucinde, 1800 (1907). See R. Haym, Die romantische Schule (1870); I. Rouge, F. Schlegel et la genie du romantisme allemand (1904); by the same, Erläuterungen zu F. Schlegels „Lucinde“ (1905); M. Joachimi, Die Weltanschauung der Romantik (1905); W. Glawe, Die Religion F. Schlegels (1906); E. Kircher, Philosophie der Romantik (1906); M. Frank "Unendliche Annäherung". Die Anfänge der philosophischen Frühromantik (1997); Andrew Bowie, From Romanticism to Critical Theory: The Philosophy of German Literary Theory (1997).

Notes

1. Frederick C. Beiser, German Idealism: The Struggle Against Subjectivism, 1781–1801, Harvard University Press, 2002, p. 349.

2. Asko Nivala, The Romantic Idea of the Golden Age in Friedrich Schlegel's Philosophy of History, Routledge, 2017, p. 23.

3. Elizabeth Millan, Friedrich Schlegel and the Emergence of Romantic Philosophy, SUNY Press, 2012, p. 49.

4. Brian Leiter, Michael Rosen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Continental Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 175: "[The word 'historicism'] appears as early as the late eighteenth century in the writings of the German romantics, who used it in a neutral sense. In 1797 Friedrich Schlegel used 'historicism' to refer to a philosophy that stresses the importance of history ..."; Katherine Harloe, Neville Morley (eds.), Thucydides and the Modern World: Reception, Reinterpretation and Influence from the Renaissance to the Present, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 81: "Already in Friedrich Schlegel's Fragments about Poetry and Literature (a collection of notes attributed to 1797), the word Historismusoccurs five times."

5. Angela Esterhammer (ed.), Romantic Poetry, Volume 7, John Benjamins Publishing, 2002, p. 491.

6. Michael N. Forster, Kristin Gjesdal (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of German Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 81.

7. Michael N. Forster, After Herder: Philosophy of Language in the German Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 9.

8. Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

9. "Friedrich – Französisch-Übersetzung – Langenscheidt Deutsch-Französisch Wörterbuch" (in German and French). Langenscheidt. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

10. "Duden | Schlegel | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition". Duden (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2018.

11. Speight (, Allen 2007). "Friedrich Schlegel". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy..

12. Watkins, Calvert (2000), "Aryan", American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.), New York: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-82517-2, ...when Friedrich Schlegel, a German scholar who was an important early Indo-Europeanist, came up with a theory that linked the Indo-Iranian words with the German word Ehre, 'honor', and older Germanic names containing the element ario-, such as the Swiss [sic] warrior Ariovistus who was written about by Julius Caesar. Schlegel theorized that far from being just a designation of the Indo-Iranians, the word *arya- had in fact been what the Indo-Europeans called themselves, meaning [according to Schlegel] something like 'the honorable people.' (This theory has since been called into question.)

13. Schlegel, Friedrich. 1819. Review of J. G. Rhode, Über den Anfang unserer Geschichte und die letzte Revolution der Erde, Breslau, 1819. Jahrbücher der Literatur VIII: 413ff

14. Ernst Behler, German Romantic Literary Theory, 1993, p. 36.

15. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Böhme, Traugott (1920). "Schlegel, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von" . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

16. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Schlegel, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

17. Adam Zamoyski (2007), Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna, pp. 242–243.

Further reading

• Berman, Antoine. L'épreuve de l'étranger. Culture et traduction dans l'Allemagne romantique: Herder, Goethe, Schlegel, Novalis, Humboldt, Schleiermacher, Hölderlin., Paris, Gallimard, Essais, 1984. ISBN 978-2-07-070076-9

• Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy, The Literary Absolute: The Theory of Literature in German Romanticism, Albany: State University Press of New York, 1988. [A philosophical exegesis of early romantic theory focused on F. Schlegel, Novalis, and the Athenaeum.]

External links

• Works by Friedrich Schlegel at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Friedrich Schlegel at Internet Archive

• Works by Friedrich Schlegel at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Dictionary of Art

• "Schlegel, Friedrich von" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

• "Schlegel, Friedrich von" . The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

• "Friedrich von Schlegel" . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

• "Schlegel, Friedrich von" . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

• Works by Friedrich Schlegel at Projekt Gutenberg-DE (in German)

• "Works by Friedrich Schlegel". Zeno.org (in German).

• Franz Muncker (1891), "Schlegel, Friedrich von", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 33, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 737–752

• "Friedrich Schlegel". Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German).

• Literature by and about Friedrich Schlegel in the German National Library catalogue

• Schlegel, Friedrich von, 1841 "Lectures on the History of Literature, Ancient and Modern". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Schlegel, Friedrich von, 1772–1829; Robertson, James Burton, 1800–1877, 1846 "The philosophy of history : in a course of lectures, delivered at Vienna". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Schiller, Friedrich, 1759–1805; Körner, Christian Gottfried, 1756–1831; Simpson, Leonard Francis, translated 1849 "Correspondence of Schiller with Körner. Comprising sketches and anecdotes of Goethe, the Schlegels, Wielands, and other contemporaries". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Schlegel, Friedrich von, 1855 "The philosophy of life, and Philosophy of language, in a course of lectures". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Friedrich von Schlegel, Ellen J . Millington, 1860 "The Aesthetic and Miscellaneous Works of Friedrich Von Schlegel". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Samuel Paul Capen, 1903 "Friedrich Schlegel's Relations with Reichardt and His Contributions to "Deutschland"". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Wilson, Augusta Manie, 1908 "The principle of the ego in philosophy with special reference to its influence upon Schlegel's doctrine of "ironie"". Retrieved 2010-09-24.

• Calvin Thomas, 1913 "Friedrich Schlegel, Introduction to Lucinda". Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36135

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

August Wilhelm Schlegel

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

August Schlegel

Born: 8 September 1767, Hanover, Electorate of Hanover

Died: 12 May 1845 (aged 77), Bonn, Rhine Province

Alma mater: University of Göttingen

Era: 19th-century philosophy

Region: Western Philosophy

School: Jena Romanticism; Historicism[1]

Institutions: University of Bonn

Main interests: Philology, philosophy of history

Influences: Immanuel Kant, J. G. Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder[2]

August Wilhelm (after 1812: von) Schlegel (/ˈʃleɪɡəl/; German: [ˈʃleːgl̩]; 8 September 1767 – 12 May 1845), usually cited as August Schlegel, was a German poet, translator and critic, and with his brother Friedrich Schlegel the leading influence within Jena Romanticism. His translations of Shakespeare turned the English dramatist's works into German classics.[3] Schlegel was also the professor of Sanskrit in Continental Europe and produced a translation of the Bhagavad Gita.

Life

The Marktkirche at the beginning of the 19th century; oil painting after Domenico Quaglio, 1832

Schlegel was born in Hanover, where his father, Johann Adolf Schlegel, was a Lutheran pastor. He was educated at the Hanover gymnasium and at the University of Göttingen.[4] Initially studying theology, he received a thorough philological training under Heyne and became an admirer and friend of Bürger, with whom he was engaged in an ardent study of Dante, Petrarch and Shakespeare. Schlegel met with Caroline Böhmer and Wilhelm von Humboldt. In 1790 his brother Friedrich came to Göttingen. Both were influenced by Johann Gottfried Herder, Immanuel Kant, Tiberius Hemsterhuis, Johann Winckelmann and Karl Theodor von Dalberg. From 1791 to 1795, Schlegel was tutor to the children of Mogge Muilman, a Dutch banker, who lived at the prestigious Herengracht in Amsterdam.[5]

In 1796, soon after his return to Germany, Schlegel settled in Jena, following an invitation from Schiller.[6] That year he married Caroline, the widow of the physician Böhmer.[4] She assisted Schlegel in some of his literary productions, and the publication of her correspondence in 1871 established for her a posthumous reputation as a German letter writer. She separated from Schlegel in 1801 and became the wife of the philosopher Schelling soon after.[6]

In Jena, Schlegel made critical contributions to Schiller's Horen and that author's Musen-Almanach,[4] and wrote around 300 articles for the Jenaer Allgemeine Litteratur-Zeitung. He also did translations from Dante and Shakespeare. This work established his literary reputation and gained for him in 1798 an extraordinary professorship at the University of Jena. His house became the intellectual headquarters of the "romanticists", and was visited at various times between 1796 and 1801 by Fichte, whose Foundations of the Science of Knowledge was studied intensively, by his brother Friedrich, who moved in with his wife Dorothea, by Schelling, by Tieck, by Novalis and others.[6]

Schlegel c. 1800

In 1797 August and Friedrich broke with Friedrich Schiller. With his brother, Schlegel founded the Athenaeum (1798–1800), the organ of the Romantic school, in which he dissected disapprovingly the immensely popular works of the sentimental novelist August Lafontaine.[8] He also published a volume of poems and carried on a controversy with Kotzebue. At this time the two brothers were remarkable for the vigour and freshness of their ideas and commanded respect as the leaders of the new Romantic criticism. A volume of their joint essays appeared in 1801 under the title Charakteristiken und Kritiken. His play Ion, performed in Weimar in January 1802, was supported by Goethe, but became a failure.

In 1801 Schlegel went to Berlin, where he delivered lectures on art and literature; and in the following year he published Ion, a tragedy in Euripidean style, which gave rise to a suggestive discussion on the principles of dramatic poetry. This was followed by Spanisches Theater (2 vols, 1803/1809), in which he presented admirable translations of five of Calderón's plays. In another volume, Blumensträusse italienischer, spanischer und portugiesischer Poesie (1804), he gave translations of Spanish, Portuguese and Italian lyrics. He also translated works by Dante and Camões.[4][3]

Early in 1804, he made the acquaintance of Madame de Staël in Berlin, who hired him as a tutor for her children. After divorcing his wife Caroline, Schlegel travelled with Madame de Staël to Switzerland, Italy and France, acting as an adviser in her literary work.[9] In 1807 he attracted much attention in France by an essay in the French, Comparaison entre la Phèdre de Racine et celle d'Euripide, in which he attacked French classicism from the standpoint of the Romantic school. His famous lectures on dramatic art and literature (Über dramatische Kunst und Literatur, 1809–1811), which have been translated into most European languages, were delivered at Vienna in 1808.[4][6] He was accompanied by De Staël and her children. In 1810 Schlegel was ordered to leave the Swiss Confederation as an enemy of the French literature.[10]

In 1812, he travelled with De Staël, her fiancé Albert de Rocca and her children to Moscow, St. Petersburg and Stockholm and acted as secretary of Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, through whose influence the right of his family to noble rank was revived. After this, he joined again the household of Mme. de Staël until her death in 1817, for like Mathieu de Montmorency he was one of her intimates until the end of her life. Schlegel was made a professor of literature at the University of Bonn in 1818, and during the remainder of his life occupied himself chiefly with oriental studies. He founded a special printing office for Sanskrit. As an orientalist, he was unable to adapt himself to the new methods opened up by Bopp.[4][6] He corresponded with Wilhelm von Humboldt, a linguist. After the death of Madame de Staël, Schlegel married (1818) a daughter of Heinrich Paulus, but this union was dissolved in 1821.[4]

Schlegel continued to lecture on art and literature, publishing in 1827 On the Theory and History of the Plastic Arts,[3] and in 1828 two volumes of critical writings (Kritische Schriften). In 1823–30 he published the journal Indische Bibliothek. In 1823 edited the Bhagavad Gita, with a Latin translation, and in 1829, the Ramayana. This was followed by his 1832 work Reflections on the Study of the Asiatic Languages.[3][4] Schlegel's translation of Shakespeare, begun in Jena, was ultimately completed, under the superintendence of Ludwig Tieck, by Tieck's daughter Dorothea and Wolf Heinrich Graf von Baudissin. This rendering is considered one of the best poetical translations in German, or indeed in any language.[4] In 1826, Felix Mendelssohn, at the age of 17, was inspired by August Wilhelm's translation of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream to write a homonymous concert overture. Schlegel's brother Friedrich's wife was an aunt of Mendelssohn.[11]