Part 2 of 2

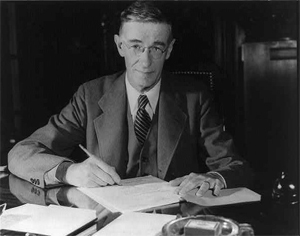

Manhattan ProjectBush played a critical role in persuading the United States government to undertake a crash program to create an atomic bomb.[64] When the NDRC was formed, the Committee on Uranium was placed under it, reporting directly to Bush as the Uranium Committee. Bush reorganized the committee, strengthening its scientific component by adding Tuve, George B. Pegram, Jesse W. Beams, Ross Gunn and Harold Urey.[65] When the OSRD was formed in June 1941, the Uranium Committee was again placed directly under Bush. For security reasons, its name was changed to the Section S-1.[66]

Left to right: Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Major General Leslie Groves and Colonel Franklin Matthias at the Hanford Site in July 1945

Left to right: Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Major General Leslie Groves and Colonel Franklin Matthias at the Hanford Site in July 1945Bush met with Roosevelt and Vice President Henry A. Wallace on October 9, 1941, to discuss the project. He briefed Roosevelt on Tube Alloys, the British atomic bomb project and its Maud Committee, which had concluded that an atomic bomb was feasible, and on the German nuclear energy project, about which little was known. Roosevelt approved and expedited the atomic program. To control it, he created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself—although he never attended a meeting—Wallace, Bush, Conant, Stimson and the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George Marshall.[67] On Bush's advice, Roosevelt chose the army to run the project rather than the navy, although the navy had shown far more interest in the field, and was already conducting research into atomic energy for powering ships. Bush's negative experiences with the Navy had convinced him that it would not listen to his advice, and could not handle large-scale construction projects.[68][69]

In March 1942, Bush sent a report to Roosevelt outlining work by Robert Oppenheimer on the nuclear cross section of uranium-235. Oppenheimer's calculations, which Bush had George Kistiakowsky check, estimated that the critical mass of a sphere of Uranium-235 was in the range of 2.5 to 5 kilograms, with a destructive power of around 2,000 tons of TNT. Moreover, it appeared that plutonium might be even more fissile.[70] After conferring with Brigadier General Lucius D. Clay about the construction requirements, Bush drew up a submission for $85 million in fiscal year 1943 for four pilot plants, which he forwarded to Roosevelt on June 17, 1942. With the Army on board, Bush moved to streamline oversight of the project by the OSRD, replacing the Section S-1 with a new S-1 Executive Committee.[71]

Bush soon became dissatisfied with the dilatory way the project was run, with its indecisiveness over the selection of sites for the pilot plants. He was particularly disturbed at the allocation of an AA-3 priority, which would delay completion of the pilot plants by three months. Bush complained about these problems to Bundy and Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson. Major General Brehon B. Somervell, the commander of the army's Services of Supply, appointed Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves as project director in September. Within days of taking over, Groves approved the proposed site at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and obtained a AAA priority. At a meeting in Stimson's office on September 23 attended by Bundy, Bush, Conant, Groves, Marshall Somervell and Stimson, Bush put forward his proposal for steering the project by a small committee answerable to the Top Policy Group. The meeting agreed with Bush, and created a Military Policy Committee chaired by him, with Somervell's chief of staff, Brigadier General Wilhelm D. Styer, representing the army, and Rear Admiral William R. Purnell representing the navy.[72]

At the meeting with Roosevelt on October 9, 1941, Bush advocated cooperating with the United Kingdom, and he began corresponding with his British counterpart, Sir John Anderson.[73] But by October 1942, Conant and Bush agreed that a joint project would pose security risks and be more complicated to manage. Roosevelt approved a Military Policy Committee recommendation stating that information given to the British should be limited to technologies that they were actively working on and should not extend to post-war developments.[74] In July 1943, on a visit to London to learn about British progress on antisubmarine technology,[75] Bush, Stimson, and Bundy met with Anderson, Lord Cherwell, and Winston Churchill at 10 Downing Street. At the meeting, Churchill forcefully pressed for a renewal of interchange, while Bush defended current policy. Only when he returned to Washington did he discover that Roosevelt had agreed with the British. The Quebec Agreement merged the two atomic bomb projects, creating the Combined Policy Committee with Stimson, Bush and Conant as United States representatives.[76]

Bush appeared on the cover of Time magazine on April 3, 1944.[77] He toured the Western Front in October 1944, and spoke to ordnance officers, but no senior commander would meet with him. He was able to meet with Samuel Goudsmit and other members of the Alsos Mission, who assured him that there was no danger from the German project; he conveyed this assessment to Lieutenant General Bedell Smith.[78] In May 1945, Bush became part of the Interim Committee formed to advise the new president, Harry S. Truman, on nuclear weapons.[79] It advised that the atomic bomb should be used against an industrial target in Japan as soon as possible and without warning.[80] Bush was present at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range on July 16, 1945, for the Trinity nuclear test, the first detonation of an atomic bomb.[81] Afterwards, he took his hat off to Oppenheimer in tribute.[82]

Before the end of the Second World War, Bush and Conant had foreseen and sought to avoid a possible nuclear arms race. Bush proposed international scientific openness and information sharing as a method of self-regulation for the scientific community, to prevent any one political group gaining a scientific advantage. Before nuclear research became public knowledge, Bush used the development of biological weapons as a model for the discussion of similar issues, an "opening wedge". He was less successful in promoting his ideas in peacetime with President Harry Truman, than he had been under wartime conditions with Roosevelt.[2][83]

In "As We May Think", an essay published by the Atlantic Monthly in July 1945, Bush wrote: "This has not been a scientist's war; it has been a war in which all have had a part. The scientists, burying their old professional competition in the demand of a common cause, have shared greatly and learned much. It has been exhilarating to work in effective partnership."[84]

Post-war years

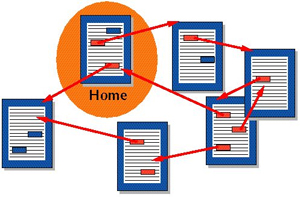

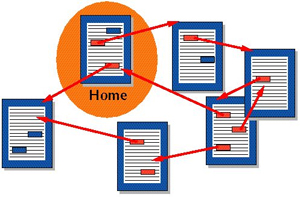

Memex conceptBush introduced the concept of the memex during the 1930s, which he imagined as a form of memory augmentation involving a microfilm-based "device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory."[84] He wanted the memex to emulate the way the brain links data by association rather than by indexes and traditional, hierarchical storage paradigms, and be easily accessed as "a future device for individual use ... a sort of mechanized private file and library" in the shape of a desk.[84] The memex was also intended as a tool to study the brain itself.[84]

Bush conceived the encyclopedia of the future as having a mesh of associative trails running through it, stored in a memex system.

Bush conceived the encyclopedia of the future as having a mesh of associative trails running through it, stored in a memex system.After thinking about the potential of augmented memory for several years, Bush set out his thoughts at length in "As We May Think", predicting that "wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified".[84] "As We May Think" was published in the July 1945 issue of The Atlantic. A few months later, Life magazine published a condensed version of "As We May Think", accompanied by several illustrations showing the possible appearance of a memex machine and its companion devices.[85]

Shortly after "As We May Think" was originally published, Douglas Engelbart read it, and with Bush's visions in mind, commenced work that would later lead to the invention of the mouse.[86] Ted Nelson, who coined the terms "hypertext" and "hypermedia", was also greatly influenced by Bush's essay.[87][88]

"As We May Think" has turned out to be a visionary and influential essay.[89] In their introduction to a paper discussing information literacy as a discipline, Bill Johnston and Sheila Webber wrote in 2005 that:

Bush's paper might be regarded as describing a microcosm of the information society, with the boundaries tightly drawn by the interests and experiences of a major scientist of the time, rather than the more open knowledge spaces of the 21st century. Bush provides a core vision of the importance of information to industrial / scientific society, using the image of an "information explosion" arising from the unprecedented demands on scientific production and technological application of World War II. He outlines a version of information science as a key discipline within the practice of scientific and technical knowledge domains. His view encompasses the problems of information overload and the need to devise efficient mechanisms to control and channel information for use.[90]

Bush was concerned that information overload might inhibit the research efforts of scientists. Looking to the future, he predicted a time when "there is a growing mountain of research. But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers."[84]

National Science FoundationThe OSRD continued to function actively until some time after the end of hostilities, but by 1946–1947 it had been reduced to a minimal staff charged with finishing work remaining from the war period; Bush was calling for its closure even before the war had ended. During the war, the OSRD had issued contracts as it had seen fit, with just eight organizations accounting for half of its spending. MIT was the largest to receive funds, with its obvious ties to Bush and his close associates. Efforts to obtain legislation exempting the OSRD from the usual government conflict of interest regulations failed, leaving Bush and other OSRD principals open to prosecution. Bush therefore pressed for OSRD to be wound up as soon as possible.[91]

With its dissolution, Bush and others had hoped that an equivalent peacetime government research and development agency would replace the OSRD. Bush felt that basic research was important to national survival for both military and commercial reasons, requiring continued government support for science and technology; technical superiority could be a deterrent to future enemy aggression. In Science, The Endless Frontier, a July 1945 report to the president, Bush maintained that basic research was "the pacemaker of technological progress". "New products and new processes do not appear full-grown," Bush wrote in the report. "They are founded on new principles and new conceptions, which in turn are painstakingly developed by research in the purest realms of science!"[92] In Bush's view, the "purest realms" were the physical and medical sciences; he did not propose funding the social sciences.[93] In Science, The Endless Frontier, science historian Daniel Kevles later wrote, Bush "insisted upon the principle of Federal patronage for the advancement of knowledge in the United States, a departure that came to govern Federal science policy after World War II."[94]

Bush (left) with Harry S. Truman (center) and James B. Conant (right)

Bush (left) with Harry S. Truman (center) and James B. Conant (right)In July 1945, the Kilgore bill was introduced in Congress, proposing the appointment and removal of a single science administrator by the president, with emphasis on applied research, and a patent clause favoring a government monopoly. In contrast, the competing Magnuson bill was similar to Bush's proposal to vest control in a panel of top scientists and civilian administrators with the executive director appointed by them. The Magnuson bill emphasized basic research and protected private patent rights.[95] A compromise Kilgore–Magnuson bill of February 1946 passed the Senate but expired in the House because Bush favored a competing bill that was a virtual duplicate of Magnuson's original bill.[96] A Senate bill was introduced in February 1947 to create the National Science Foundation (NSF) to replace the OSRD. This bill favored most of the features advocated by Bush, including the controversial administration by an autonomous scientific board. The bill passed the Senate and the House, but was pocket vetoed by Truman on August 6, on the grounds that the administrative officers were not properly responsible to either the president or Congress.[97] The OSRD was abolished without a successor organization on December 31, 1947.[98]

Without a National Science Foundation, the military stepped in, with the Office of Naval Research (ONR) filling the gap. The war had accustomed many scientists to working without the budgetary constraints imposed by pre-war universities.[99] Bush helped create the Joint Research and Development Board (JRDB) of the Army and Navy, of which he was chairman. With passage of the National Security Act on July 26, 1947, the JRDB became the Research and Development Board (RDB). Its role was to promote research through the military until a bill creating the National Science Foundation finally became law.[100] By 1953, the Department of Defense was spending $1.6 billion a year on research; physicists were spending 70 percent of their time on defense related research, and 98 percent of the money spent on physics came from either the Department of Defense or the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which took over from the Manhattan Project on January 1, 1947.[101] Legislation to create the National Science Foundation finally passed through Congress and was signed into law by Truman in 1950.[102]

The authority that Bush had as chairman of the RDB was much different from the power and influence he enjoyed as director of OSRD and would have enjoyed in the agency he had hoped would be independent of the Executive branch and Congress. He was never happy with the position and resigned as chairman of the RDB after a year, but remained on the oversight committee.[103] He continued to be skeptical about rockets and missiles, writing in his 1949 book, Modern Arms and Free Men, that intercontinental ballistic missiles would not be technically feasible "for a long time to come ... if ever".[104]

Later lifeWith Truman as president, men like John R. Steelman, who was appointed chairman of the President's Scientific Research Board in October 1946, came to prominence.[105] Bush's authority, both among scientists and politicians, suffered a rapid decline, though he remained a revered figure.[106] In September 1949, he was appointed to head a scientific panel that included Oppenheimer to review the evidence that the Soviet Union had tested its first atomic bomb. The panel concluded that it had, and this finding was relayed to Truman, who made the public announcement.[107] Bush was outraged when a security hearing stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance in 1954; he issued a strident attack on Oppenheimer's accusers in The New York Times. Alfred Friendly summed up the feeling of many scientists in declaring that Bush had become "the Grand Old Man of American science".[108]

Bush continued to serve on the NACA through 1948 and expressed annoyance with aircraft companies for delaying development of a turbojet engine because of the huge expense of research and development as well as retooling from older piston engines.[109] He was similarly disappointed with the automobile industry, which showed no interest in his proposals for more fuel-efficient engines. General Motors told him that "even if it were a better engine, [General Motors] would not be interested in it."[110] Bush likewise deplored trends in advertising. "Madison Avenue believes", he said, "that if you tell the public something absurd, but do it enough times, the public will ultimately register it in its stock of accepted verities."[111]

From 1947–1962, Bush was on the board of directors for American Telephone and Telegraph. He retired as president of the Carnegie Institution and returned to Massachusetts in 1955,[108] but remained a director of Metals and Controls Corporation from 1952–1959, and of Merck & Co. 1949–1962.[112] Bush became chairman of the board at Merck following the death of George W. Merck, serving until 1962. He worked closely with the company's president, Max Tishler, although Bush was concerned about Tishler's reluctance to delegate responsibility. Bush distrusted the company's sales organization, but supported Tishler's research and development efforts.[113] He was a trustee of Tufts College 1943–1962, of Johns Hopkins University 1943–1955, of the Carnegie Corporation of New York 1939–1950, the Carnegie Institution of Washington 1958–1974, and the George Putnam Fund of Boston 1956–1972, and was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution 1943–1955.[114]

Bush received the AIEE's Edison Medal in 1943, "for his contribution to the advancement of electrical engineering, particularly through the development of new applications of mathematics to engineering problems, and for his eminent service to the nation in guiding the war research program."[115] In 1945, Bush was awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences.[116] In 1949, he received the IRI Medal from the Industrial Research Institute in recognition of his contributions as a leader of research and development.[114] President Truman awarded Bush the Medal of Merit with bronze oak leaf cluster in 1948, President Lyndon Johnson awarded him the National Medal of Science in 1963,[117] and President Richard Nixon presented him with the Atomic Pioneers Award from the Atomic Energy Commission in February 1970.[118] Bush was also made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1948, and an Officer of the French Legion of Honor in 1955.[114]

After suffering a stroke, Bush died in Belmont, Massachusetts, at the age of 84 from pneumonia on June 28, 1974. He was survived by his sons Richard (a surgeon) and John (president of Millipore Corporation) and by six grandchildren and his sister Edith. Bush's wife had died in 1969.[119] He was buried at South Dennis Cemetery in South Dennis, Massachusetts,[120] after a private funeral service. At a public memorial subsequently held by MIT,[121] Jerome Wiesner declared "No American has had greater influence in the growth of science and technology than Vannevar Bush".[112]

In 1980, the National Science Foundation created the Vannevar Bush Award to honor his contributions to public service.[122] The Vannevar Bush papers are located in several places, with the majority of the collection held at the Library of Congress. Additional papers are held by the MIT Institute Archives and Special Collections, the Carnegie Institution, and the National Archives and Records Administration.[123][124][125]

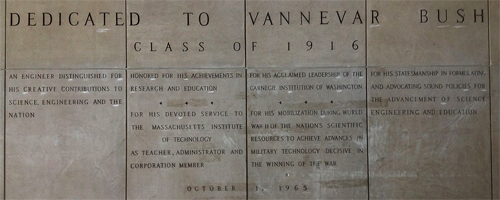

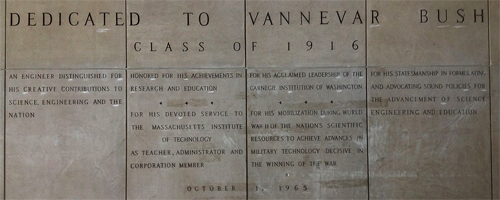

This inscription honoring Vannevar Bush is

in the lobby of MIT's Building 13, which is named after him, and is

the home of the Center for Materials Science and Engineering.[126]See also• List of pioneers in computer science

Bibliography(For a complete list of his published papers, see Wiesner 1979, pp. 107–117).

• Bush, Vannevar; Timbie, William H. (1922). Principles of Electrical Engineering. John Wiley & Sons – via Internet Archive.

• Bush, Vannevar; Wiener, Norbert (1929). Operational Circuit Analysis. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. OCLC 2167931.

• —— (1945). Science, the Endless Frontier: a Report to the President. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1594001. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

• —— (1946). Endless Horizons. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press. OCLC 1152058.

• —— (1949). Modern Arms and Free Men: a Discussion of the Role of Science in Preserving Democracy. New York: Simon and Schuster. OCLC 568075.

• Bush, Vannevar (1967). Science Is Not Enough. New York: Morrow. OCLC 520108.

• Bush, Vannevar (1970). Pieces of the Action. New York: Morrow. OCLC 93366.

Notes1. "Vannevar Bush". Computer Science Tree. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

2. Meyer, Michal (2018). "The Rise and Fall of Vannevar Bush". Distillations. Science History Institute. 4 (2): 6–7. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

3. Houston, Ronald D.; Harmon, Glynn (2007). "Vannevar Bush and memex". Annual Review of Information Science and Technology. 41 (1): 55–92. doi:10.1002/aris.2007.1440410109.

4. Zachary 1997, pp. 12–13.

5. Zachary 1997, p. 22.

6. Zachary 1997, pp. 25–27.

7. "Vannevar Bush's profile tracer". National Museum of American History. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

8. Wiesner 1979, pp. 90–91.

9. Zachary 1997, pp. 28–32.

10. Puchta 1996, p. 58.

11. Zachary 1997, pp. 41, 245.

12. Zachary 1997, pp. 33–38.

13. Owens 1991, p. 15.

14. Zachary 1997, pp. 39–43.

15. "History of Our Company". Sensata Technologies. Archived from the original on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

16. "Raytheon Company". International Directory of Company Histories. St. James Press. 2001. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

17. Owens 1991, pp. 6–11.

18. Brittain 2008, pp. 2132–2133.

19. Wiesner 1979, p. 106.

20. L.E.P. (1929). "Review of Operational Circuit Analysis by Vannevar Bush". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 208 (1): 131–132. doi:10.1016/S0016-0032(29)90969-8.

21. "Claude E. Shannon, an oral history conducted in 1982 by Robert Price". IEEE Global History Network. New Brunswick, New Jersey: IEEE History Center. 1982. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

22. "MIT Professor Claude Shannon dies; was founder of digital communications". MIT News. February 27, 2001. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

23. Zachary 1997, pp. 76–78.

24. Zachary 1997, pp. 55–56.

25. Zachary 1997, pp. 83–85.

26. Zachary 1997, pp. 91–95.

27. Zachary 1997, p. 93.

28. Zachary 1997, p. 94.

29. Zachary 1997, pp. 98–99.

30. Evans, Ryan Thomas (2010). "Aviation at sunrise: shortcomings of the American Air Forces in North Africa during TORCH compared to the Royal Air Force on Malta, 1941–1942". WWU Masters Thesis Collection. Western Washington University. pp. 34–38. Paper 76. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

31. Roland 1985, p. 427.

32. Zachary 1997, pp. 104–112.

33. Zachary 1997, p. 129.

34. Stewart 1948, p. 7.

35. Zachary 1997, p. 119.

36. Stewart 1948, pp. 10–12.

37. Zachary 1997, p. 106.

38. Zachary 1997, p. 125.

39. Zachary 1997, pp. 124–127.

40. Conant 2002, pp. 168–169, 182.

41. Zachary 1997, pp. 132–134.

42. Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp., 180 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 673, p. 20, finding 1.1.3 (U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, Fourth Division 1973) ("... the ENIAC machine was being operated rather than tested after 1 December 1945.").

43. Zachary 1997, p. 266–267.

44. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (June 28, 1941). "Executive Order 8807 Establishing the Office of Scientific Research and Development". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

45. Zachary 1997, pp. 127–129.

46. Stewart 1948, p. 189.

47. Stewart 1948, p. 185.

48. Stewart 1948, p. 190.

49. Stewart 1948, p. 322.

50. Zachary 1997, pp. 130–131.

51. Zachary 1997, pp. 124–125.

52. Stewart 1948, p. 276.

53. Reinholds, Robert. "Dr. Vannevar Bush is dead at 84; Dr. Vannevar Bush, who marshaled nation's wartime technology and ushered in Atomic Age, is dead at 84". GN. The New York Times. p. 1.

54. Furer 1959, pp. 346–347.

55. "Section T "Proximity Fuze" Records, 1940–[1999] (bulk 1941–1943)". Carnegie Institution of Washington. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

56. Christman 1998, pp. 86–91.

57. Furer 1959, p. 348.

58. Furer 1959, p. 349.

59. Zachary 1997, pp. 176, 180–183.

60. Baxter 1946, p. 241.

61. Zachary 1997, p. 179.

62. Zachary 1997, p. 177.

63. Bush 1970, p. 307.

64. Goldberg 1992, p. 451.

65. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 25.

66. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 40–41.

67. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 45–46.

68. Zachary 1997, p. 203.

69. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 51, 71–72.

70. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 61.

71. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 72–75.

72. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 78–83.

73. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 259–260.

74. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 264–270.

75. Zachary 1997, p. 211.

76. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 276–280.

77. "Dr. Vannevar Bush". Time. XLIII (14). April 3, 1944.

78. Bush 1970, pp. 114–116.

79. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 344–345.

80. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 360–361.

81. Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 378.

82. Zachary 1997, p. 280.

83. Wellerstein, Alex (July 25, 2012). "Biological Warfare: Vannevar Bush's "Entering Wedge" (1944)". Restricted Data. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

84. Bush, Vannevar (July 1945). "As We May Think". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

85. Bush, Vannevar (September 10, 1945). "As We May Think". Life. pp. 112–124. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

86. "A Lifetime Pursuit". Doug Engelbart Institute. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

87. "Hypertext". Doug Engelbart Institute. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

88. Crawford 1996, p. 671.

89. Buckland 1992, p. 284.

90. Johnston & Webber 2006, p. 109.

91. Zachary 1997, pp. 246–249.

92. "Science the Endless Frontier: A Report to the President by Vannevar Bush, Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development". National Science Foundation. July 1945. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

93. Greenberg 2001, pp. 44–45.

94. Greenberg 2001, p. 52.

95. Zachary 1997, pp. 253–256.

96. Zachary 1997, p. 328.

97. Zachary 1997, p. 332.

98. "Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD)". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

99. Hershberg 1993, p. 397.

100. Zachary 1997, pp. 318–323.

101. Hershberg 1993, pp. 305–309.

102. Zachary 1997, pp. 368–369.

103. Zachary 1997, pp. 336–345.

104. Hershberg 1993, p. 393.

105. Zachary 1997, pp. 330–331.

106. Zachary 1997, pp. 346–347.

107. Zachary 1997, pp. 348–349.

108. Zachary 1997, pp. 377–378.

109. Dawson 1991, p. 80.

110. Zachary 1997, p. 387.

111. Zachary 1997, p. 386.

112. Wiesner 1979, p. 108.

113. Werth 1994, p. 132.

114. Wiesner 1979, p. 107.

115. "Vannevar Bush". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

116. "Public Welfare Award". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

117. "The President's National Medal of Science". National Science Foundation. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

118. Nixon, Richard (February 27, 1970). "Remarks on Presenting the Atomic Pioneers Award". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

119. Wiesner 1979, p. 105.

120. "Dennis 1974 Annual Town Reports" (PDF). Retrieved June 14, 2012.

121. Zachary 1997, p. 407.

122. "Vannevar Bush Award". National Science Foundation. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

123. "Vannevar Bush Papers, 1921–1975". Manuscript Collection. MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections. MC 78. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

124. "Vannevar Bush Papers 1901–1974". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

125. "Carnegie Institution of Washington Administration Records, 1890–2001". Carnegie Institution of Washington. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

126. Wiesner 1979, p. 101.

References• Baxter, James Phinney (1946). Scientists Against Time. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC 1084158.

• Brittain, James E. (December 2008). "Electrical Engineering Hall of Fame: Vannevar Bush". Proceedings of the IEEE. 96 (12): 2131. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2008.2006199.

• Buckland, Michael (May 1992). "Emanuel Goldberg, electronic document retrieval, and Vannevar Bush's Memex". Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 43 (4): 284–294. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-4571(199205)43:4<284::aid-asi3>3.0.co;2-0.

• Conant, Jennet (2002). Tuxedo Park. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-87287-2. OCLC 48966735.

• Christman, Albert B. (1998). Target Hiroshima: Deak Parsons and the creation of the atomic bomb. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-120-2. OCLC 38257982.

• Crawford, T. Hugh (Winter 1996). "Paterson, Memex, and hypertext". American Literary History. 8 (4): 665–682. doi:10.1093/alh/8.4.665. JSTOR 490117.

• Dawson, Virginia P. (1991). Engines and Innovation: Lewis Laboratory and American propulsion technology. Scientific and Technical Information Division. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. ISBN 978-0-16-030742-3. OCLC 22665627. Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

• Furer, Julius Augustus (1959). Administration of the Navy Department in World War II. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1915787.

• Goldberg, Stanley (September 1992). "Inventing a climate of opinion: Vannevar Bush and the decision to build the bomb". Isis. 83 (3): 429–452. doi:10.1086/356203. JSTOR 233904.

• Greenberg, Daniel S. (2001). Science, Money, and Politics: Political triumph and ethical erosion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30634-6. OCLC 45661689.

• Hershberg, James G. (1993). James B. Conant: Harvard to Hiroshima and the making of the nuclear age. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-57966-5. OCLC 27678159.

• Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07186-5. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

• Johnston, Bill; Webber, Sheila (2006). "As We May Think: Information literacy as a discipline for the information age". Research Strategies. 20 (3): 108–121. doi:10.1016/j.resstr.2006.06.005. ISSN 0734-3310.

• Owens, Larry (1991). "Vannevar Bush and the Differential Analyzer: The text and context of and early computer". In Nyce, James M.; Kahn, Paul (eds.). From Memex to Hypertext: Vannevar Bush and the mind's machine. Boston, MA: Academic Press. pp. 3–38. ISBN 978-0-12-523270-8. OCLC 24870981.

• Puchta, Susann (Winter 1996). "On the role of mathematics and mathematical knowledge in the invention of Vannevar Bush's early analog computers". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 18 (4): 49–59. doi:10.1109/85.539916.

• Roland, Alex (1985). Model Research. Scientific and Technical Information Branch. 2. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. SP-4103. Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

• Stewart, Irvin (1948). Organizing Scientific Research for War: The administrative history of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company. OCLC 500138898. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

• Wiesner, Jerome B. (1979). Vannevar Bush, 1890–1974: A biographical memoir (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences of the United States. OCLC 79828818. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

• Werth, Barry (1994). The Billion-Dollar Molecule: One company's quest for the perfect drug. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-72327-9. OCLC 28721852.

• Zachary, G. Pascal (1997). Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, engineer of the American century. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-82821-3. OCLC 36521020.

External links• "Vannevar Bush papers, 1901–1974". Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

• "Vannevar Bush papers, 1910–1988". Tufts University. hdl:10427/57028.

• "MIT Web Museum".

• "1995 MIT / Brown U. Vannevar Bush Symposium". complete video archive.

• "The Vannevar Bush Index". Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

• Video demonstrating the ideas behind the Memex system on YouTube

• "Pictures of Vannevar Bush". Tufts Digital Library.

• "Biographical Memoir" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences.