Oscar Wilde

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/4/20

Sir Richard Somers Travers Christmas Humphreys (4 August 1867 – 20 February 1956) was a noted British barrister and judge who, during a sixty-year legal career, was involved in the cases of Oscar Wilde and the murderers Hawley Harvey Crippen, George Joseph Smith and John George Haigh, the 'Acid Bath Murderer', among many others.

Travers Humphreys was born in Doughty Street in Bloomsbury in London, the fourth son and sixth child of solicitor Charles Octavius Humphreys, and his wife, Harriet Ann (née Grain), the sister of the entertainer Richard Corney Grain. Humphreys was educated at Shrewsbury School and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, graduating BA in 1889. He was called to the Bar from the Inner Temple in 1889 and entered the chambers of E. T. E. Besley, where he concentrated on practice in the criminal courts.

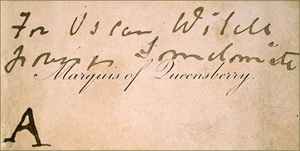

On 1 March 1895 Oscar Wilde, Lord Alfred Douglas and Robbie Ross approached [his father] Charles Octavius Humphreys with the intention of suing the Marquess of Queensberry, Douglas' father, for criminal libel. Humphreys applied for a warrant for Queensberry's arrest and approached Sir Edward Clarke and Charles Willie Mathews to represent Wilde. Travers Humphreys appeared as a Junior Counsel for the prosecution in the subsequent case of Wilde vs Queensbury.

On 28 May 1896 Humphreys married the actress Zoë Marguerite (1872–1953), the daughter of Henri Philippe Neumans, an artist from Antwerp. In 1895 she had appeared in An Artist's Model with Marie Tempest, Marie Studholme, Letty Lind and Hayden Coffin. They had two sons, the elder of whom, Richard Grain Humphreys (1897-28 September 1917) was killed in France in the Third Battle of Ypres during World War I; the younger son was the noted barrister and judge Christmas Humphreys, who prosecuted Ruth Ellis for the murder of her lover David Blakely in 1955 [and Founder of The Buddhist Society]

-- Travers Humphreys, by Wikipedia

James Martineau, by Wikipedia: (Unitarian): Oscar Wilde references him in his prose.

***

George Bernard Shaw, by Wikipedia: Of contemporary dramatists writing for the West End stage he rated Oscar Wilde above the rest: "... our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audience, with the whole theatre".

***

W.B. Yeats, by Wikipedia: The influence of Oscar Wilde is evident in Yeats's theory of aesthetics, especially in his stage plays, and runs like a motif through his early works. The theory of masks, developed by Wilde in his polemic The Decay of Lying can clearly be seen in Yeats's play The Player Queen, while the more sensual characterisation of Salomé, in Wilde's play of the same name, provides the template for the changes Yeats made in his later plays, especially in On Baile's Strand (1904), Deirdre (1907), and his dance play The King of the Great Clock Tower (1934).

***

Julius Evola, by Wikipedia: In his teenage years, Evola immersed himself in painting—which he considered one of his natural talents—and literature, including Oscar Wilde and Gabriele d'Annunzio.

***

Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, by Wikipedia: Oscar Wilde dedicated his play Lady Windermere's Fan to him.

***

Florence Farr [Mary Lester], by Wikipedia: Beatrice Emery (née) Farr was a British West End leading actress, composer and director. She was also a women's rights activist, journalist, educator, singer, novelist, and leader of the occult order, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. She was a friend and collaborator of Nobel laureate William Butler Yeats, poet Ezra Pound, playwright Oscar Wilde, artists Aubrey Beardsley and Pamela Colman Smith, Masonic scholar Arthur Edward Waite, theatrical producer Annie Horniman, and many other literati of London's Fin de siècle era.

***

John Ruskin, by Wikipedia: Most controversial, from the point of view of the University authorities, spectators and the national press, was the digging scheme on Ferry Hinksey Road at North Hinksey, near Oxford, instigated by Ruskin in 1874, and continuing into 1875, which involved undergraduates in a road-mending scheme. The scheme was motivated in part by a desire to teach the virtues of wholesome manual labour. Some of the diggers, which included Oscar Wilde, Alfred Milner and Ruskin's future secretary and biographer, W. G. Collingwood, were profoundly influenced by the experience: notably Arnold Toynbee, Leonard Montefiore and Alexander Robertson MacEwen.

***

Max Stirner [Johann Kaspar Schmidt], by Wikipedia: Stirner's main work is The Ego and Its Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigenthum), which appeared in Leipzig in October 1844, with as year of publication mentioned 1845. In The Ego And Its Own, Stirner launches a radical anti-authoritarian and individualist critique of contemporary Prussian society and modern western society as such. He offers an approach to human existence in which he depicts himself as "the unique one", a "creative nothing", beyond the ability of language to fully express:If I concern myself for myself, the unique one, then my concern rests on its transitory, mortal creator, who consumes himself, and I may say: All things are nothing to me.

The book proclaims that all religions and ideologies rest on empty concepts. The same holds true for society's institutions that claim authority over the individual, be it the state, legislation, the church, or the systems of education such as universities…In the time of spirits thoughts grew till they overtopped my head, whose offspring they yet were; they hovered about me and convulsed me like fever-phantasies – an awful power. The thoughts had become corporeal on their own account, were ghosts, e. g. God, Emperor, Pope, Fatherland, etc. If I destroy their corporeity, then I take them back into mine, and say: "I alone am corporeal." And now I take the world as what it is to me, as mine, as my property; I refer all to myself…

Oscar Wilde's The Soul of Man Under Socialism has caused some historians to speculate that Wilde (who could read German) was familiar with the book.

***

-- Jawaharlal Nehru: An Autobiography, 1936: My general attitude to life at the time was a vague kind of cyrenaicism, partly natural to youth, partly the influence of Oscar Wilde and Walter Pater. It is easy and gratifying to give a long Greek name to the desire for a soft life and pleasant experiences. But there was something more in it than that for I was not particularly attracted to a soft life. Not having the religious temper and disliking the repressions of religion, It was natural for me to seek some other standard. I was superficial and did not go deep down into anything. And so the aesthetic side of life appealed to me, and the idea of going through life worthily, not indulging it in the vulgar way, but still making the most of it and living a full and many-sided life attracted me. I enjoyed life and I refused to see why I should consider it a thing of sin. At the same time risk and adventure fascinated me; I was always, like my father, a bit of a gambler, at first with money and then for higher stakes, with the bigger issues of life. Indian politics in 1907 and 1908 were in a state of upheaval and I wanted to play a brave part in them, and this was not likely to lead to a soft life. All these mixed and sometimes conflicting desires led to a medley in my mind. Vague and confused it was but I did not worry, for the time for any decision was yet far distant. Meanwhile, life was pleasant, both physically and intellectually, fresh horizons were ever coming into sight, there was so much to be done, so much to be seen, so many fresh avenues to explore. And we would sit by the fireside in the long winter evenings and talk and discuss unhurriedly deep into the night till the dying fire drove us shivering to our beds. And sometimes, during our discussions, our voices would lose their even tenor and would grow loud and excited in heated argument. But it was all make-believe. We played with the problems of human life in a mock-serious way; for they had not become real problems for us yet, and we had not been caught in the coils of the world's affairs. It was the pre-war world of the early twentieth century. Soon this world was to die, yielding place to another, full of death and destruction and anguish and heart-sickness for the world's youth. But the veil of the future hid this and we saw around us an assured and advancing order of things and this was pleasant for those who could afford it.

I write of cyrenaicism and the like and of various ideas that influenced me then. But it would be wrong to imagine that I thought clearly on these subjects then or even that I thought it necessary to try to be clear and definite about them. They were just vague fancies that floated in my mind and in this process left their impress in a greater or less degree. I did not worry myself at all about these speculations. Work and games and amusements filled my life and the only thing that disturbed me sometimes was the political struggle in India.

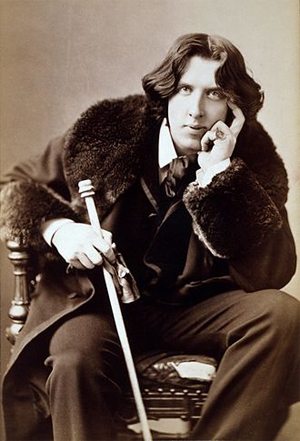

Oscar Wilde

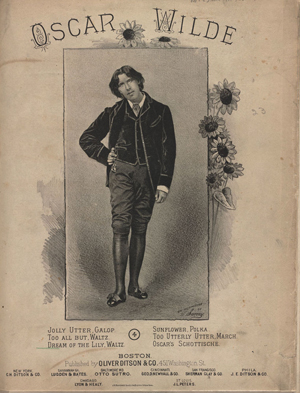

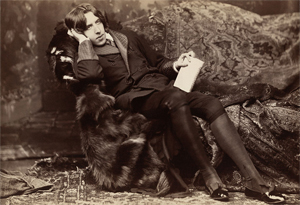

Wilde in 1882

Born: Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde, 16 October 1854, Dublin, Ireland

Died: 30 November 1900 (aged 46), Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris, France

Buried: Père Lachaise Cemetery

Occupation: Author, poet, playwright

Language: English, French, Greek

Nationality: Irish

Education: Portora Royal School

Alma mater: Trinity College, Dublin; Magdalen College, Oxford

Period: Victorian era

Genre: Epigram, drama, short story, criticism, journalism

Literary movement: Aesthetic movement; Decadent movement

Notable works: The Picture of Dorian Gray; The Importance of Being Earnest

Spouse: Constance Lloyd (m. 1884; died 1898)

Children: Cyril Holland; Vyvyan Holland

Relatives: Sir William Wilde (father); Lady Jane Wilde (mother); Willie Wilde (brother); Isola Wilde (Sister)

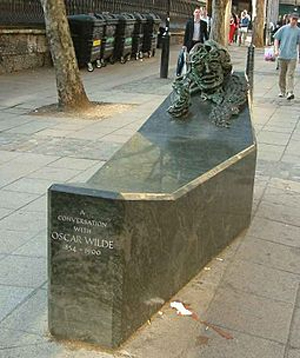

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, the early 1890s saw him become one of the most popular playwrights in London. He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the circumstances of his criminal conviction for gross indecency for consensual homosexual acts, imprisonment, and early death at age 46.

Wilde's parents were Anglo-Irish intellectuals in Dublin. A young Wilde learned to speak fluent French and German. At university, Wilde read Greats; he demonstrated himself to be an exceptional classicist, first at Trinity College Dublin, then at Oxford. He became associated with the emerging philosophy of aestheticism, led by two of his tutors, Walter Pater and John Ruskin. After university, Wilde moved to London into fashionable cultural and social circles.

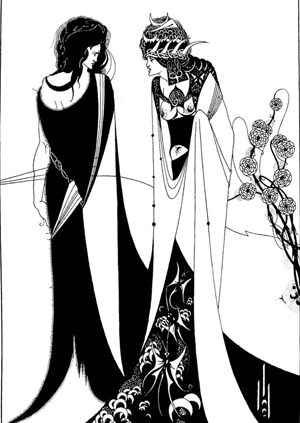

As a spokesman for aestheticism, he tried his hand at various literary activities: he published a book of poems, lectured in the United States and Canada on the new "English Renaissance in Art" and interior decoration, and then returned to London where he worked prolifically as a journalist. Known for his biting wit, flamboyant dress and glittering conversational skill, Wilde became one of the best-known personalities of his day. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into what would be his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, and combine them with larger social themes, drew Wilde to write drama. He wrote Salome (1891) in French while in Paris but it was refused a licence for England due to an absolute prohibition on the portrayal of Biblical subjects on the English stage.

Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late-Victorian London.

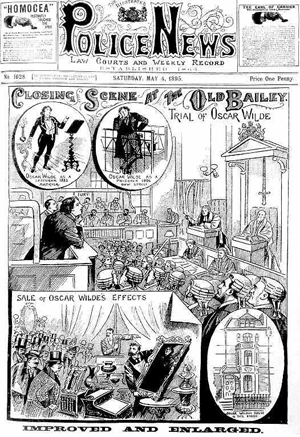

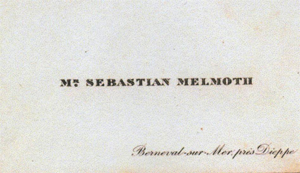

At the height of his fame and success, while The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) was still being performed in London, Wilde prosecuted the Marquess of Queensberry for criminal libel. The Marquess was the father of Wilde's lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. The libel trial unearthed evidence that caused Wilde to drop his charges and led to his own arrest and trial for gross indecency with men. After two more trials he was convicted and sentenced to two years' hard labour, the maximum penalty, and was jailed from 1895 to 1897. During his last year in prison, he wrote De Profundis (published posthumously in 1905), a long letter which discusses his spiritual journey through his trials, forming a dark counterpoint to his earlier philosophy of pleasure. On his release, he left immediately for France, never to return to Ireland or Britain. There he wrote his last work, The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898), a long poem commemorating the harsh rhythms of prison life.

Early life

The Wilde family home on Merrion Square

Oscar Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin (now home of the Oscar Wilde Centre, Trinity College), the second of three children born to an Anglo-Irish couple: Jane, née Elgee and Sir William Wilde. Oscar was two years younger than his brother, William (Willie) Wilde.

Jane Wilde was a niece (by marriage) of the novelist, playwright and clergyman Charles Maturin (1780 – 1824), who may have influenced her own literary career. She had distant Italian ancestry,[1] and under the pseudonym "Speranza" (the Italian word for 'hope'), she wrote poetry for the revolutionary Young Irelanders in 1848; she was a lifelong Irish nationalist.[2] Jane Wilde read the Young Irelanders' poetry to Oscar and Willie, inculcating a love of these poets in her sons.[3] Her interest in the neo-classical revival showed in the paintings and busts of ancient Greece and Rome in her home.[3]

Jane Francesca Agnes, Lady Wilde (née Elgee; 27 December 1821 – 3 February 1896) was an Irish poet under the pen name "Speranza" and supporter of the nationalist movement. Lady Wilde had a special interest in Irish folktales, which she helped to gather.

She married Sir William Wilde, an eye and ear surgeon (and also a researcher of folklore),...The Rosicrucians searched and studied the Gospels, particularly that of St. John, from the point of view of their esoteric teachings, and found content for meditation in their wisdom. They taught by means of pictures and symbols, appealing to imagination rather than intellect. They can only be understood if the student himself is able to develop imaginative faculties. The Rosicrucians tried to evoke imaginative effort and ability in all sorts of ways, not only through pictures and tablets, but through a wealth of fairy tales, legends proverbs and songs -- even to children's games and acrobatic feats. By all these means, they were able to bring the content of esoteric wisdom to the people, in the form of picture and parable, and at the same time to educate in the people the faculties needed to understand them. By thus educating the individual imagination of ordinary folk, they developed initiative and resource, abilities very necessary to deal with the new experiences brought by scientific discoveries to ordinary men.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it was essential to hide religious and philosophical ideas if they did not coincide with the dogmas of the Church, for this was the era of the Inquisition. Here was another reason for the need to hide the new spiritual teachings in parables and allegory. Hieronymus Bosch had cause to fear the Inquisition which took an ever firmer grip on the people of the Netherlands in his time. He was one of the most important transmitters of Rosicrucian teachings.

Beside his imaginations and symbols, there appears many a "sign" in which he characterises the spiritual difficulties of his time, or answers the persecutors. One can recognise throughout a sort of secret language through which the intimate members of the Rosicrucian brotherhood communicated.

-- The Pictorial Language of Hieronymus Bosch, by Clement A. Wertheim Aymes

on 12 November 1851 in St. Peter's church in Dublin, and they had three children: William Charles Kingsbury Wilde (26 September 1852 – 13 March 1899), Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900), and Isola Francesca Emily Wilde (2 April 1857 – 23 February 1867). Her eldest son William Wilde became a journalist and poet, her younger son Oscar Wilde became a prolific and famous writer, and her daughter Isola Wilde died in childhood.

Jane was the last of the four children of Charles Elgee (1783–1824), a Wexford solicitor, and his wife Sarah (née Kingsbury, d. 1851). Her great-grandfather was an Italian who had come to Wexford in the 18th century. Lady Wilde, who was the niece of Charles Maturin, wrote for the Young Ireland movement of the 1840s, publishing poems in The Nation under the pseudonym of Speranza. Her works included pro-Irish independence and anti-British writing; she was sometimes known as "Speranza of the Nation". Charles Gavan Duffy was the editor when "Speranza" wrote commentary calling for armed revolution in Ireland. The authorities at Dublin Castle shut down the paper and brought the editor to court. Duffy refused to name who had written the offending article. "Speranza" reputedly stood up in court and claimed responsibility for the article. The confession was ignored by the authorities. But in any event the newspaper was permanently shut down by the authorities.Young Ireland was a political, cultural and social movement of the mid-19th century. It began as a tendency within Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association, associated with The Nation newspaper, but eventually split to found the Irish Confederation in 1847. Young Ireland led changes in Irish nationalism, including an abortive rebellion known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Many of the rebellion's leaders were tried for sedition and sentenced to penal transportation to Van Diemen's Land. From its beginnings in the late 1830s, Young Ireland grew in influence and inspired following generations of Irish nationalists. Some of the junior members of the movement went on to found the Irish Republican Brotherhood...The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924. Its counterpart in the United States of America was initially the Fenian Brotherhood, but from the 1870s it was Clan na Gael. The members of both wings of the movement are often referred to as "Fenians". The IRB played an important role in the history of Ireland, as the chief advocate of republicanism during the campaign for Ireland's independence from the United Kingdom, successor to movements such as the United Irishmen of the 1790s and the Young Irelanders of the 1840s.

As part of the New Departure of the 1870s–80s, IRB members attempted to democratise the Home Rule League, and its successor, the Irish Parliamentary Party, as well as taking part in the Land War. The IRB staged the Easter Rising in 1916, which led to the establishment of the first Dáil Éireann in 1919. The suppression of Dáil Éireann precipitated the Irish War of Independence and the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, ultimately leading to the establishment of the Irish Free State, which excluded the territory of Northern Ireland.

-- Irish Republican Brotherhood, by Wikipedia

Young Ireland traced its origins to the new College Historical Society, founded on 29 March 1839, at a meeting at Francis Kearney's chambers, 27 College. Among the members of this new society were Charles Gavan Duffy; Jane Wilde; Margaret Callan; John Mitchel; Thomas Meagher; William Smith O'Brien; John Blake Dillon, Thomas MacNevin, William Eliot Hudson and Thomas Davis, who was elected its president in 1840. While still at Trinity College, Davis had addressed the Dublin Historical Society, which met at the Dorset Institute in Upper Sackville Street from 1836 to 1838. Davis became president and gave two lectures. (Available from the National Library of Ireland, the lectures clearly show that Davis had become a convinced Irish nationalist by this period.

-- Young Ireland, by Wikipedia

She was an early advocate of women's rights, and campaigned for better education for women. She invited the suffragist Millicent Fawcett to her home to speak on female liberty. She praised the passing of the Married Women's Property Act of 1883, which prevented a woman from having to enter marriage 'as a bond slave, disenfranchised of all rights over her fortune'.

William Wilde was knighted in January 1864, but the family celebrations were short-lived, for in the same year Sir William and Lady Wilde were at the centre of a sensational Dublin court case regarding a young woman called Mary Travers, the daughter of a colleague of Sir William's, who claimed that he had seduced her and who then brought an action against Lady Wilde for libel. Mary Travers won the case and costs of £2,000 were awarded against Lady Wilde. Then on 23 February 1867, their daughter Isola died of fever at the age of nine. In 1871 the two illegitimate daughters of Sir William burned to death in an accident and in 1876 Sir William himself died. The family discovered that he was virtually bankrupt.

Lady Wilde left Dublin for London in 1879, where she joined her two sons, Willie, a journalist, and Oscar, who was making a name for himself in literary circles. She lived with her older son in poverty, supplementing their meagre income by writing for fashionable magazines and producing books based on the researches of her late husband into Irish folklore.

Lady Wilde contracted bronchitis in January 1896 and, dying, asked for permission to see Oscar, who was in prison. Her request was refused. It was claimed that her "fetch" (i.e. her apparition) appeared in Oscar's prison cell as she died at her home, 146 Oakley Street, Chelsea, on 3 February 1896. Willie Wilde, her older son, was penniless, so Oscar paid for her funeral, which was held on 5 February at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.[10] A headstone proved too expensive and she was buried anonymously in common ground.

-- Jane Wilde, by Wikipedia

Annie Besant (née Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, writer, orator, educationist, and philanthropist. Regarded as a champion of human freedom, she was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule....

Her mother was an Irish Catholic, from a family of more modest means. Besant would go on to make much of her Irish ancestry and supported the cause of Irish self-rule throughout her adult life. Her cousin Kitty O'Shea (born Katharine Wood) was noted for having an affair with Charles Stewart Parnell [an Irish nationalist politician who served as Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1882 to 1891 and Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882.], leading to his downfall...

In 1867, at age twenty, she married 26-year-old clergyman Frank Besant (1840–1917), younger brother of Walter Besant. He was an evangelical Anglican who seemed to share many of her concerns. On the eve of her marriage, she had become more politicised through a visit to friends in Manchester, who brought her into contact with both English radicals and the Manchester Martyrs of the Irish Republican Fenian Brotherhood, as well as with the conditions of the urban poor...The Fenian Brotherhood (Irish: Bráithreachas na bhFíníní) was an Irish republican organisation founded in the United States in 1858 by John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny. It was a precursor to Clan na Gael, a sister organisation to the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Members were commonly known as "Fenians". O'Mahony, who was a Gaelic scholar, named his organisation after the Fianna, the legendary band of Irish warriors led by Fionn mac Cumhaill.

The Fenian Brotherhood trace their origins back to 1790s, in the rebellion, seeking an end to British rule in Ireland initially for self-government and then the establishment of an Irish Republic. The rebellion was suppressed, but the principles of the United Irishmen were to have a powerful influence on the course of Irish history.

-- Fenian Brotherhood, by Wikipedia

Besant built close contacts with the Irish Home Rulers and supported them in her newspaper columns during what are considered crucial years, when the Irish nationalists were forming an alliance with Liberals and Radicals. Besant met the leaders of the Irish home rule movement. In particular, she got to know Michael Davitt, who wanted to mobilise the Irish peasantry through a Land War, a direct struggle against the landowners. She spoke and wrote in favour of Davitt and his Land League many times over the coming decades...

In 1916 Besant launched the All India Home Rule League along with Lokmanya Tilak, once again modelling demands for India on Irish nationalist practices.

-- Annie Besant, by Wikipedia

William Wilde was Ireland's leading oto-ophthalmologic (ear and eye) surgeon and was knighted in 1864 for his services as medical adviser and assistant commissioner to the censuses of Ireland.[4] He also wrote books about Irish archaeology and peasant folklore. A renowned philanthropist, his dispensary for the care of the city's poor at the rear of Trinity College, Dublin, was the forerunner of the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital, now located at Adelaide Road.[4] On his father's side Wilde was descended from a Dutchman, Colonel de Wilde, who went to Ireland with King William of Orange's invading army in 1690, and numerous Anglo-Irish ancestors. On his mother's side, Wilde's ancestors included a bricklayer from County Durham, who emigrated to Ireland sometime in the 1770s.[5][6]

Wilde was baptised as an infant in St. Mark's Church, Dublin, the local Church of Ireland (Anglican) church. When the church was closed, the records were moved to the nearby St. Ann's Church, Dawson Street.[7] Davis Coakley mentions a second baptism by a Catholic priest, Father Prideaux Fox, who befriended Oscar's mother circa 1859. According to Fox's testimony in Donahoe's Magazine in 1905, Jane Wilde would visit his chapel in Glencree, County Wicklow, for Mass and would take her sons with her. She asked Father Fox in this period to baptise her sons.[8]

Fox described it in this way:

"I am not sure if she ever became a Catholic herself but it was not long before she asked me to instruct two of her children, one of them being the future erratic genius, Oscar Wilde. After a few weeks I baptized these two children, Lady Wilde herself being present on the occasion.

In addition to his children with his wife, Sir William Wilde was the father of three children born out of wedlock before his marriage: Henry Wilson, born in 1838 to one woman, and Emily and Mary Wilde, born in 1847 and 1849, respectively, to a second woman. Sir William acknowledged paternity of his illegitimate or "natural" children and provided for their education, arranging for them to be reared by his relatives rather than with his legitimate children in his family household with his wife.[9]

In 1855, the family moved to No. 1 Merrion Square, where Wilde's sister, Isola, was born in 1857. The Wildes' new home was larger. With both his parents' success and delight in social life, the house soon became the site of a "unique medical and cultural milieu". Guests at their salon included Sheridan Le Fanu, Charles Lever, George Petrie, Isaac Butt, William Rowan Hamilton and Samuel Ferguson.[3]

Until he was nine, Oscar Wilde was educated at home, where a French nursemaid and a German governess taught him their languages.[10] He attended Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, from 1864 to 1871.[11] Until his early twenties, Wilde summered at the villa, Moytura House, which his father had built in Cong, County Mayo.[12] There the young Wilde and his brother Willie played with George Moore.

Isola died at age nine of meningitis. Wilde's poem "Requiescat" is written to her memory.[13]

"Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow

Speak gently, she can hear

the daisies grow"

University education: 1870s

Trinity College, Dublin

Wilde left Portora with a royal scholarship to read classics at Trinity College, Dublin, from 1871 to 1874,[14] sharing rooms with his older brother Willie Wilde. Trinity, one of the leading classical schools, placed him with scholars such as R. Y. Tyrell, Arthur Palmer, Edward Dowden and his tutor, Professor J. P. Mahaffy, who inspired his interest in Greek literature. As a student Wilde worked with Mahaffy on the latter's book Social Life in Greece.[15] Wilde, despite later reservations, called Mahaffy "my first and best teacher" and "the scholar who showed me how to love Greek things".[16] For his part, Mahaffy boasted of having created Wilde; later, he said Wilde was "the only blot on my tutorship".[17]

Oscar Wilde was a student of [John Pentland Mahaff] at Trinity and he is said to have influenced Wilde’s conversational style. The two were close for a time, visiting Greece together; Wilde proofread the first edition of Mahaffy’s Social Life in Greece (1874), which contained a remarkably open consideration of Greek homosexuality (removed from later editions). But the friendship cooled over political and aesthetic differences, and after Wilde’s conviction Mahaffy declined to refer to him and refused to sign a petition calling for his early release.

-- Battle of wits – An Irishman’s Diary on Trinity and John Pentland Mahaffy, by Brian Maye, The Irish Times, 4/23/19

The University Philosophical Society also provided an education, as members discussed intellectual and artistic subjects such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne weekly. Wilde quickly became an established member -– the members' suggestion book for 1874 contains two pages of banter (sportingly) mocking Wilde's emergent aestheticism. He presented a paper titled "Aesthetic Morality".[18] At Trinity, Wilde established himself as an outstanding student: he came first in his class in his first year, won a scholarship by competitive examination in his second and, in his finals, won the Berkeley Gold Medal in Greek, the University's highest academic award.[19] He was encouraged to compete for a demyship to Magdalen College, Oxford –- which he won easily, having already studied Greek for over nine years.

Magdalen College, Oxford

At Magdalen, he read Greats from 1874 to 1878, and from there he applied to join the Oxford Union, but failed to be elected.[20]

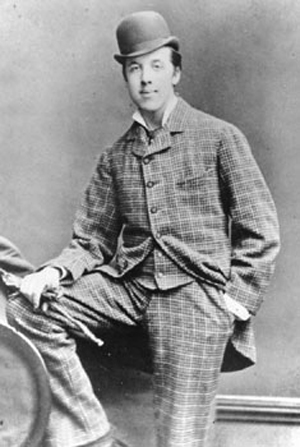

Oscar Wilde at Oxford

Attracted by its dress, secrecy, and ritual, Wilde petitioned the Apollo Masonic Lodge at Oxford, and was soon raised to the "Sublime Degree of Master Mason".[21] During a resurgent interest in Freemasonry in his third year, he commented he "would be awfully sorry to give it up if I secede from the Protestant Heresy".[22] Wilde's active involvement in Freemasonry lasted only for the time he spent at Oxford; he allowed his membership of the Apollo University Lodge to lapse after failing to pay subscriptions.[23]

Apollo University Lodge No 357 is a Masonic Lodge based at the University of Oxford aimed at past and present members of the university. It was consecrated in 1819, and its members have met continuously since then.

Membership of the lodge is restricted to those who have matriculated as members of the University of Oxford. The Lodge's historic records, from its foundation until 2005, are housed in the university's Bodleian Library. The lodge is primarily a part of university social life, but is also involved in other areas of university life through projects such as the Apollo Bursary, administered by the university, through which lodge members provide financial support to certain students.

Due to its association with the university it has had famous members such as Cecil Rhodes, Oscar Wilde, and Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.

-- Apollo University Lodge, by Wikipedia

Catholicism deeply appealed to him, especially its rich liturgy, and he discussed converting to it with clergy several times. In 1877, Wilde was left speechless after an audience with Pope Pius IX in Rome.[24] He eagerly read the books of Cardinal Newman, a noted Anglican priest who had converted to Catholicism and risen in the church hierarchy. He became more serious in 1878, when he met the Reverend Sebastian Bowden, a priest in the Brompton Oratory who had received some high-profile converts. Neither his father, who threatened to cut off his funds, nor Mahaffy thought much of the plan; but Wilde, the supreme individualist, balked at the last minute from pledging himself to any formal creed, and on the appointed day of his baptism, sent Father Bowden a bunch of altar lilies instead. Wilde did retain a lifelong interest in Catholic theology and liturgy.[25]

While at Magdalen College, Wilde became particularly well known for his role in the aesthetic and decadent movements. He wore his hair long, openly scorned "manly" sports though he occasionally boxed,[21] and he decorated his rooms with peacock feathers, lilies, sunflowers, blue china and other objets d'art. He once remarked to friends, whom he entertained lavishly, "I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china."[26] The line quickly became famous, accepted as a slogan by aesthetes but used against them by critics who sensed in it a terrible vacuousness.[26] Some elements disdained the aesthetes, but their languishing attitudes and showy costumes became a recognised pose.[27] Wilde was once physically attacked by a group of four fellow students, and dealt with them single-handedly, surprising critics.[28] By his third year Wilde had truly begun to develop himself and his myth, and considered his learning to be more expansive than what was within the prescribed texts. This attitude resulted in his being rusticated for one term, after he had returned late to a college term from a trip to Greece with Mahaffy.[29]

Wilde did not meet Walter Pater until his third year, but had been enthralled by his Studies in the History of the Renaissance, published during Wilde's final year in Trinity.[30] Pater argued that man's sensibility to beauty should be refined above all else, and that each moment should be felt to its fullest extent. Years later, in De Profundis, Wilde described Pater's Studies... as "that book that has had such a strange influence over my life".[31] He learned tracts of the book by heart, and carried it with him on travels in later years. Pater gave Wilde his sense of almost flippant devotion to art, though he gained a purpose for it through the lectures and writings of critic John Ruskin.[32] Ruskin despaired at the self-validating aestheticism of Pater, arguing that the importance of art lies in its potential for the betterment of society. Ruskin admired beauty, but believed it must be allied with, and applied to, moral good. When Wilde eagerly attended Ruskin's lecture series The Aesthetic and Mathematic Schools of Art in Florence, he learned about aesthetics as the non-mathematical elements of painting. Despite being given to neither early rising nor manual labour, Wilde volunteered for Ruskin's project to convert a swampy country lane into a smart road neatly edged with flowers.[32]

Wilde won the 1878 Newdigate Prize for his poem "Ravenna", which reflected on his visit there the year before, and he duly read it at Encaenia.[33] In November 1878, he graduated with a double first in his B.A. of Classical Moderations and Literae Humaniores (Greats). Wilde wrote to a friend, "The dons are 'astonied' beyond words – the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!"[34][35]

Apprenticeship of an aesthete: 1880s

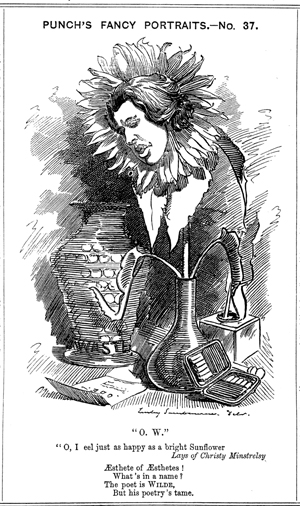

1881 caricature in Punch, the caption reads: "O.W.", "Oh, I eel just as happy as a bright sunflower, Lays of Christy Minstrelsy, "Æsthete of Æsthetes!/What's in a name!/The Poet is Wilde/But his poetry's tame." "The Big Sunflower'" was a time-honoured blackface minstrel song. W. Sheppard of the Original Christy Minstrels made it famous and other performers sang it for decades afterwards.[36]

Debut in society

After graduation from Oxford, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he met again Florence Balcombe, a childhood sweetheart. She became engaged to Bram Stoker and they married in 1878.[37] Wilde was disappointed but stoic: he wrote to her, remembering "the two sweet years – the sweetest years of all my youth" during which they had been close.[38] He also stated his intention to "return to England, probably for good." This he did in 1878, only briefly visiting Ireland twice after that.[38][39]

Unsure of his next step, Wilde wrote to various acquaintances enquiring about Classics positions at Oxford or Cambridge.[40] The Rise of Historical Criticism was his submission for the Chancellor's Essay prize of 1879, which, though no longer a student, he was still eligible to enter. Its subject, "Historical Criticism among the Ancients" seemed ready-made for Wilde –- with both his skill in composition and ancient learning -– but he struggled to find his voice with the long, flat, scholarly style.[41] Unusually, no prize was awarded that year.[41][note 1]

With the last of his inheritance from the sale of his father's houses, he set himself up as a bachelor in London.[43] The 1881 British Census listed Wilde as a boarder at 1 (now 44) Tite Street, Chelsea, where Frank Miles, a society painter, was the head of the household.[44] Wilde spent the next six years in London and Paris, and in the United States, where he travelled to deliver lectures.

He had been publishing lyrics and poems in magazines since entering Trinity College, especially in Kottabos and the Dublin University Magazine. In mid-1881, at 27 years old, he published Poems, which collected, revised and expanded his poems.[45]

The book was generally well received, and sold out its first print run of 750 copies. Punch was less enthusiastic, saying "The poet is Wilde, but his poetry's tame". By a tight vote, the Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism. The librarian, who had requested the book for the library, returned the presentation copy to Wilde with a note of apology.[46][47] Biographer Richard Ellmann argues that Wilde's poem "Hélas!" was a sincere, though flamboyant, attempt to explain the dichotomies the poet saw in himself; one line reads: "To drift with every passion till my soul / Is a stringed lute on which all winds can play".[48]

The book had further printings in 1882. It was bound in a rich, enamel parchment cover (embossed with gilt blossom) and printed on hand-made Dutch paper; over the next few years, Wilde presented many copies to the dignitaries and writers who received him during his lecture tours.[49]

America: 1882

Aestheticism was sufficiently in vogue to be caricatured by Gilbert and Sullivan in Patience (1881). Richard D'Oyly Carte, an English impresario, invited Wilde to make a lecture tour of North America, simultaneously priming the pump for the US tour of Patience and selling this most charming aesthete to the American public. Wilde journeyed on the SS Arizona, arriving 2 January 1882, and disembarking the following day.[50][note 2] Originally planned to last four months, it continued for almost a year due to the commercial success.[52] Wilde sought to transpose the beauty he saw in art into daily life.[36] This was a practical as well as philosophical project: in Oxford he had surrounded himself with blue china and lilies, and now one of his lectures was on interior design.

When asked to explain reports that he had paraded down Piccadilly in London carrying a lily, long hair flowing, Wilde replied, "It's not whether I did it or not that's important, but whether people believed I did it".[36] Wilde believed that the artist should hold forth higher ideals, and that pleasure and beauty would replace utilitarian ethics.[53]

Wilde and aestheticism were both mercilessly caricatured and criticised in the press; the Springfield Republican, for instance, commented on Wilde's behaviour during his visit to Boston to lecture on aestheticism, suggesting that Wilde's conduct was more a bid for notoriety rather than devotion to beauty and the aesthetic. T. W. Higginson, a cleric and abolitionist, wrote in "Unmanly Manhood" of his general concern that Wilde, "whose only distinction is that he has written a thin volume of very mediocre verse", would improperly influence the behaviour of men and women.[54]

Keller cartoon from the Wasp of San Francisco depicting Wilde on the occasion of his visit there in 1882

According to biographer Michèle Mendelssohn, Wilde was the subject of anti-Irish caricature and was portrayed as a monkey, a blackface performer and a Christy's Minstrel throughout his career.[36] "Harper's Weekly put a sunflower-worshipping monkey dressed as Wilde on the front of the January 1882 issue. The magazine didn't let its reputation for quality impede its expression of what are now considered odious ethnic and racial ideologies. The drawing stimulated other American maligners and, in England, had a full-page reprint in the Lady's Pictorial. ... When the National Republican discussed Wilde, it was to explain 'a few items as to the animal's pedigree.' And on 22 January 1882 the Washington Post illustrated the Wild Man of Borneo alongside Oscar Wilde of England and asked 'How far is it from this to this?'"[36] Though his press reception was hostile, Wilde was well received in diverse settings across America; he drank whiskey with miners in Leadville, Colorado, and was fêted at the most fashionable salons in many cities he visited.[55]

London life and marriage

His earnings, plus expected income from The Duchess of Padua, allowed him to move to Paris between February and mid-May 1883. While there he met Robert Sherard, whom he entertained constantly. "We are dining on the Duchess tonight", Wilde would declare before taking him to an expensive restaurant.[56]

The Duchess of Padua is a play by Oscar Wilde. It is a five-act melodramatic tragedy set in Padua and written in blank verse. It was written for the actress Mary Anderson in early 1883 while in Paris. After she turned it down, it was abandoned until its first performance at the Broadway Theatre in New York City under the title Guido Ferranti on 26 January 1891, where it ran for three weeks. It has been rarely revived or studied.

-- The Duchess of Padua, by Wikipedia

In August he briefly returned to New York for the production of Vera, his first play, after it was turned down in London. He reportedly entertained the other passengers with "Ave Imperatrix!, A Poem on England", about the rise and fall of empires. E. C. Stedman, in Victorian Poets, describes this "lyric to England" as "manly verse – a poetic and eloquent invocation".[57][note 3]

Wilde had to return to England, where he continued to lecture on topics including Personal Impressions of America, The Value of Art in Modern Life, and Dress.

No. 34 Tite Street, Chelsea, the Wilde family home from 1884 to his arrest in 1895. In Wilde's time this was No. 16 – the houses have been renumbered.[60]

In London, he had been introduced in 1881 to Constance Lloyd, daughter of Horace Lloyd, a wealthy Queen's Counsel, and his wife. She happened to be visiting Dublin in 1884, when Wilde was lecturing at the Gaiety Theatre. He proposed to her, and they married on 29 May 1884 at the Anglican St James's Church, Paddington, in London.[61][62] Although Constance had an annual allowance of £250, which was generous for a young woman (equivalent to about £26,300 in current value), the Wildes had relatively luxurious tastes. They had preached to others for so long on the subject of design that people expected their home to set new standards.[63] No. 16, Tite Street was duly renovated in seven months at considerable expense. The couple had two sons together, Cyril (1885) and Vyvyan (1886). Wilde became the sole literary signatory of George Bernard Shaw's petition for a pardon of the anarchists arrested (and later executed) after the Haymarket massacre in Chicago in 1886.[64]

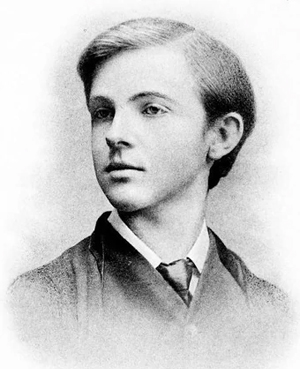

Robert Ross at twenty-four

Robert Ross had read Wilde's poems before they met at Oxford in 1886. He seemed unrestrained by the Victorian prohibition against homosexuality, and became estranged from his family. By Richard Ellmann's account, he was a precocious seventeen-year-old who "so young and yet so knowing, was determined to seduce Wilde".[65]According to Daniel Mendelsohn, Wilde, who had long alluded to Greek love, was "initiated into homosexual sex" by Ross, while his "marriage had begun to unravel after his wife's second pregnancy, which left him physically repelled".[66]

Prose writing: 1886–91

Journalism and editorship: 1886–89

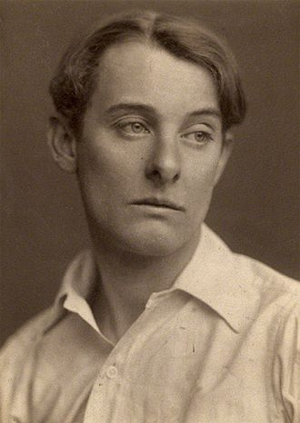

Wilde reclining with Poems, by Napoleon Sarony in New York in 1882. Wilde often liked to appear idle, though in fact he worked hard; by the late 1880s he was a father, an editor, and a writer.[67]

Criticism over artistic matters in The Pall Mall Gazette provoked a letter in self-defence, and soon Wilde was a contributor to that and other journals during 1885–87. He enjoyed reviewing and journalism; the form suited his style. He could organise and share his views on art, literature and life, yet in a format less tedious than lecturing. Buoyed up, his reviews were largely chatty and positive.[68] Wilde, like his parents before him, also supported the cause of Irish nationalism. When Charles Stewart Parnell was falsely accused of inciting murder, Wilde wrote a series of astute columns defending him in the Daily Chronicle.[64]

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1882 to 1891 and Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882. He served as a member of parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891. His party held the balance of power in the House of Commons during the Home Rule debates of 1885–1890...

Parnell's leadership was first put to the test in February 1886, when he forced the candidature of Captain William O'Shea, who had negotiated the Kilmainham Treaty, for a Galway by-election. Parnell rode roughshod over his lieutenants Healy, Dillon and O'Brien who were not in favour of O'Shea. Galway was the harbinger of the fatal crisis to come. O'Shea had already separated from his wife Katharine O'Shea [born Katharine Wood, cousin of Annie Wood Besant], but would not divorce her as she was expecting a substantial inheritance. Mrs. O'Shea acted as liaison in 1885 with Gladstone during proposals for the First Home Rule Bill. Parnell later took up residence with her in Eltham, Kent, in the summer of 1886, and was a known overnight visitor at the O'Shea house in Brockley, London. When Mrs O'Shea's aunt died in 1889, her money was left in trust.

On 24 December 1889, Captain O'Shea filed for divorce, citing Parnell as co-respondent, although the case did not come for trial until 15 November 1890. The two-day trial revealed that Parnell had been the long-term lover of Mrs. O'Shea and had fathered three of her children. Meanwhile, Parnell assured the Irish Party that there was no need to fear the verdict because he would be exonerated. During January 1890, resolutions of confidence in his leadership were passed throughout the country. Parnell did not contest the divorce action at a hearing on 15 November, to ensure that it would be granted and he could marry Mrs O'Shea, so Captain O'Shea's allegations went unchallenged. A divorce decree was granted on 17 November 1890, but Parnell's two surviving children were placed in O'Shea's custody.

News of the long-standing adultery created a huge public scandal. The Irish National League passed a resolution to confirm his leadership. The Catholic Church hierarchy in Ireland was shocked by Parnell's immorality and feared that he would wreck the cause of Home Rule. Besides the issue of tolerating immorality, the bishops sought to keep control of Irish Catholic politics, and they no longer trusted Parnell as an ally. The chief Catholic leader, Archbishop Walsh of Dublin, came under heavy pressure from politicians, his fellow bishops, and Cardinal Manning; Walsh finally declared against Parnell. Larkin (1961) says, "For the first time in Irish history, the two dominant forces of Nationalism and Catholicism came to a parting of the ways.

In England one strong base of Liberal Party support was Nonconformist Protestantism, such as the Methodists; the 'nonconformist conscience' rebelled against having an adulterer play a major role in the Liberal Party. Gladstone warned that if Parnell retained the leadership, it would mean the loss of the next election, the end of their alliance, and also of Home Rule. With Parnell obdurate, the alliance collapsed in bitterness...

Parnell next became the centre of public attention when in March and April 1887 he found himself accused by the British newspaper The Times of supporting the brutal murders in May 1882 of the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and the Permanent Under-Secretary, Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin's Phoenix Park, and of the general involvement of his movement with crime (i.e., with illegal organisations such as the IRB [Irish Republican Brotherhood]). Letters were published which suggested Parnell was complicit in the murders...

However, a Commission of Enquiry, which Parnell had requested, revealed in February 1889, after 128 sessions that the letters were a fabrication created by Richard Pigott, a disreputable anti-Parnellite rogue journalist. Pigott broke down under cross-examination after the letter was shown to be a forgery by him with his characteristic spelling mistakes. He fled to Madrid where he committed suicide. Parnell was vindicated, to the disappointment of the Tories and the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury.

-- Charles Stewart Parnell, by Wikipedia

Her mother was an Irish Catholic, from a family of more modest means. Besant would go on to make much of her Irish ancestry and supported the cause of Irish self-rule throughout her adult life. Her cousin Kitty O'Shea (born Katharine Wood) was noted for having an affair with Charles Stewart Parnell, leading to his downfall.

-- Annie Besant, by Wikipedia

His flair, having previously been put mainly into socialising, suited journalism and rapidly attracted notice. With his youth nearly over, and a family to support, in mid-1887 Wilde became the editor of The Lady's World magazine, his name prominently appearing on the cover.[69] He promptly renamed it as The Woman's World and raised its tone, adding serious articles on parenting, culture, and politics, while keeping discussions of fashion and arts. Two pieces of fiction were usually included, one to be read to children, the other for the ladies themselves. Wilde worked hard to solicit good contributions from his wide artistic acquaintance, including those of Lady Wilde and his wife Constance, while his own "Literary and Other Notes" were themselves popular and amusing.[70]

The initial vigour and excitement which he brought to the job began to fade as administration, commuting and office life became tedious.[71] At the same time as Wilde's interest flagged, the publishers became concerned anew about circulation: sales, at the relatively high price of one shilling, remained low.[72] Increasingly sending instructions to the magazine by letter, Wilde began a new period of creative work and his own column appeared less regularly.[73][74] In October 1889, Wilde had finally found his voice in prose and, at the end of the second volume, Wilde left The Woman's World.[75] The magazine outlasted him by one issue.[73]

If Wilde's period at the helm of the magazine was a mixed success from an organizational point of view, it played a pivotal role in his development as a writer and facilitated his ascent to fame. Whilst Wilde the journalist supplied articles under the guidance of his editors, Wilde the editor was forced to learn to manipulate the literary marketplace on his own terms.[76]

Wilde in 1889

During the late 1880s, Wilde was a close friend of the artist James McNeill Whistler and they dined together on many occasions. At one of these dinners, Whistler said a bon mot that Wilde found particularly witty, Wilde exclaimed that he wished that he had said it, and Whistler retorted "You will, Oscar, you will".[77] Herbert Vivian—a mutual friend of Wilde and Whistler— attended the dinner and recorded it in his article The Reminiscences of a Short Life which appeared in The Sun in 1889. The article alleged that Wilde had a habit of passing off other people's witticisms as his own—especially Whistler's. Wilde considered Vivian's article to be a scurrilous betrayal, and it directly caused the broken friendship between Wilde and Whistler.[78] The Reminiscences also caused great acrimony between Wilde and Vivian, Wilde accusing Vivian of "the inaccuracy of an eavesdropper with the method of a blackmailer"[79] and banishing Vivian from his circle.[78]