Curzon's Hour, Excerpt from "Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia"

by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac

© 1999 by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

CHAPTER TWELVE: Curzon's Hour

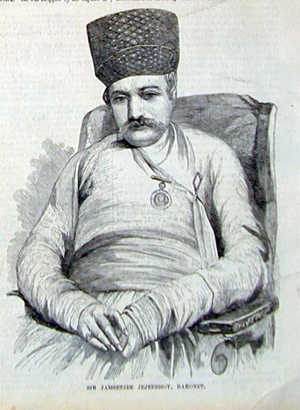

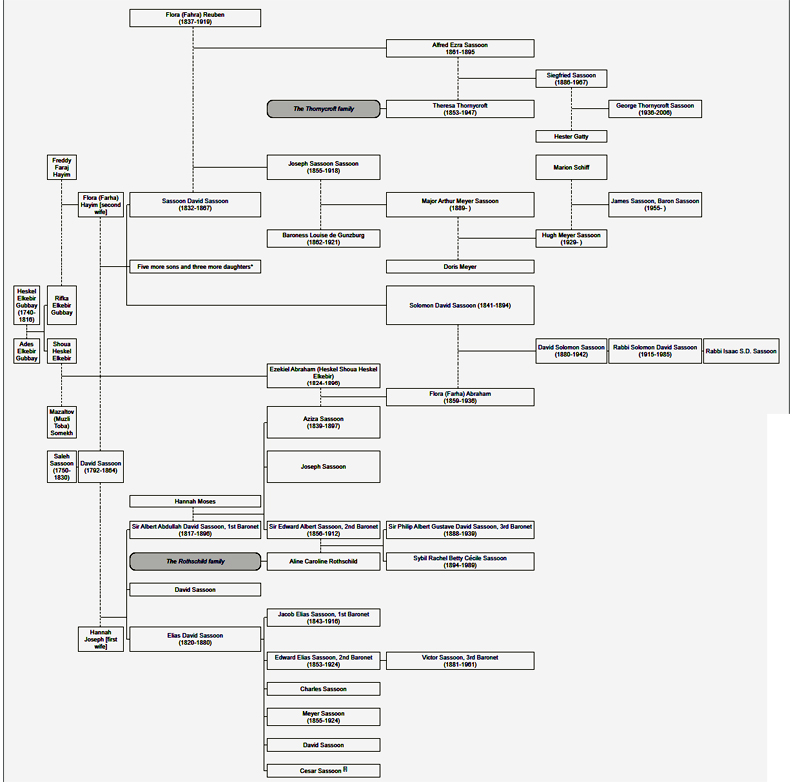

GEORGE NATHANIEL CURZON WAS NOT YET FORTY WHEN HE was named Viceroy of India, and his lovely Vicereine, nee Mary Leiter of Chicago, was not quite thirty when they sailed eastward on the P & O liner Arabia. Their arrival at Bombay on December 30, 1898, was Curzon's noontide. No Viceroy had more ardently sought the position, none was better prepared, and certainly none had seen more of what everybody then called the Orient. Not merely India and China, not just Japan, Siam, and Korea, but also Bokhara and Samarkand, the shores of the Caspian, the "singing sands" of the Sinai, the long-inaccessible Great Mosque of Kairwan in the Sahara, the throne of the Afghans in Kabul -- all this Curzon had seen. His two-volume Persia and the Persian Question (1892), for which he had worn out horses, boots, and guides, immediately became the standard authority.When his Pamirs and the Source if the Oxus (1896) won a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society, Curzon confessed the honor gave him greater pleasure "than it did to become a Minister of the Crown."

Curzon's tireless voyages were the more impressive considering his disability, a curvature of the spine that tormented him until his death in 1925. Pain was chronic, and contributed to a peevish sarcasm that so hindered his political career. The steel corset that encased his frame, writes Harold Nicolson, "gave to his figure an aspect of unbending perpendicular, affecting also the motions of his mind: there was no middle path for him between rigidity and collapse." For Curzon, everything came down to a reasoned application of a focused will. In demanding too much of himself, he too often vented scorn on the less efficient, the less driven. "Try to suffer fools more gladly," gently remonstrated his friend and putative superior, Lord George Hamilton, the Secretary of State for India in London, "they constitute the majority of mankind."

Curzon belonged to the privileged minority, and he knew it. His forebears crossed the Channel with William the Conqueror and thereafter pursued with more tenacity than distinction the family motto, "Let Curzon holde what Curzon helde." For eight centuries, the Curzons kept tenure of their estates in Derbyshire, 10,000 acres, and for generations sent a succession of Members to Parliament, most of them lackluster backbenchers. Their one indisputable achievement was construction of a Palladian masterpiece, Kedleston, whose noble exterior and majestic rooms were completed felicitously by Robert Adam. Here Curzon was born in 1859, the eldest son of the fourth Baron Scarsdale, a clergyman and, like many upper-class fathers, a nonchalant parent.

Young George, his two brothers, and six sisters were left mostly in the care of a stern governess, Miss Paraman, who succumbed to "paroxysms of ferocity" while dealing with her charges. She insisted (to quote Nicolson again) on "obedience, success and the more detailed forms of religion." The lessons of discipline stuck, but the unjust punishments he suffered bred in Curzon a combative spirit, redeemed by his quickness of mind and (when he wished) personal charm. In 1872, he entered Eton, where he won every academic prize, proved a rebellious trial to his masters, developed the curvature of his spine, suffered the loss (at sixteen) of a caring mother, and fell under the spell of the Indian Empire.

By his own account, that epiphany occurred during a spirited address to the Eton Literary Society by Sir James Fitzames Stephen, friend and adviser to Viceroy Lytton, a despiser of liberal soppiness, and uncle of the yet-unborn Virginia Woolf. Stephen said (as Curzon recalled) "that there was in the Asian continent an empire more populous, more amazing, and more beneficent than that of Rome; that the rulers of that great dominion were drawn from the men of our own people; that some of them might perhaps in the future be taken from the ranks of boys who were listening to his words." The seeds thus planted germinated at Oxford and flowered during a visit to India in 1887, when "the fascination and, if I may say so, the sacredness of India" persuaded Curzon that there was no higher honor than serving at that altar. He had found a vocation, in much the same spirit that others turn to cloth and cowl.

WHEN CURZON WENT UP TO BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD, IN 1878, he was already dubbed The Coming Man. "Everyone remarked his present eminence and predicted his future fame," recalled his near contemporary Winston Churchill. At Oxford too he seemed to waltz to the summit, becoming president of the debating society, the Oxford Union; dominating the Conservative society, the Canning Club; turning out prize-winning essays on recondite themes. Only once did his ability to cram fail him, when he gained only a Second Class rather than the all-important First in his final examination. "Now I shall devote the rest of my life to showing the examiners have made a mistake," the embarrassed paragon remarked. He compensated by winning the most coveted Oxford fellowship, to All Souls.

Still, Curzon's precocity was too amply evident. Of his speaking style, a Balliol colleague said, "He spoke copiously, even long, was more inclined to overpower than to persuade, and in repartee or sarcasm was apt to be too heavy handed." His non-admirers had their revenge in the "accursed doggerel" that followed him past the grave. In lines for a student masque, ascribed to his schoolmates J. D. Mackail and Cecil Spring Rice (later boon companion to Theodore Roosevelt), his overbearing manner was rendered thus:

My name is George Nathaniel Curzon,

I am a most superior person,

My cheek is pink, my hair is sleek,

I dine at Blenheim once a week.

Not entirely fair or accurate: the private Curzon was self-deprecatory, relished telling jokes against himself, and sought out unconventional and witty friends, one being his classmate Oscar Wilde. "You are a brick," Wilde wrote Curzon after the latter had defended the former in an undergraduate contretemps. "Our sweet city with its dreaming towers must not be given entirely over to the philistines." Curzon never shied from jousts across political fences, though his lance could be sharp. On joining a club (the Crabbet) founded by the rakish anti-imperialist Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, he once with a bland smile addressed his host: "My dear Wilfrid, your poetry is delightful and your morals, though deplorable, enchanting. But why are you a traitor to your country?" (Subsequently Curzon won the club's laureate award, with a poem in praise of sin.)

Curzon's airs were superior, but not joyless. Still, on one root question he was invariably earnest. The British Empire, he believed, was "the greatest instrument for good that the world has seen." Moreover, the noble work of governing India was "placed by the inscrutable decrees of Providence upon the shoulders of the British race." At Oxford, this claim of divine stewardship was linked to classical Greece and the teachings of Plato by the eminent theologian and professor of Greek, Benjamin Jowett, the Master of Balliol and one of the moral legislators of Victorian England.

Under Jowett, Balliol became Oxford's intellectual flagship, and his owlish countenance was among the monuments that important visitors all wished to see. He cultivated the influential, and kept a notebook listing the names of acquaintances likely to help his college or its students, his mission being "to inoculate England with Balliol." A bachelor with a grumpy distaste for small talk, "The Jowler" was easier to admire than like. His cutting remarks instantly circulated, such as his tart summary of a colleague's windy sermon: "All that I could make out was that today was yesterday, and this world the same as the next." Or as he remarked to Margot Asquith, wife of the soon-to-be Prime Minister (also of Balliol): "My dear child, you must believe in God in spite of what the clergy tell you."

Jowett had a particular interest in India; his two brothers had served and died there. Like other eminent Britons before and afterwards, he tended to see the subcontinent as a blackboard on which new theories could be chalked and analyzed. He belonged to a tradition that began with Benthamites ("the greatest happiness for the greatest number"), Christian evangelicals, and reformers like Lord Macaulay and Sir Charles Trevelyan. Liberals and conservatives alike assumed that Western education was the key to raising native peoples from sloth and ignorance. To this Jowett added a practical corollary: that the Indian Civil Service could provide India with a governing elite that was disinterested and benevolent, in the fashion of the Guardians in Plato's Republic (which Jowett translated). These Guardians were to be generalists, their minds honed by Greek and Latin, though Jowett also saw merit in studying Sanskrit, Vernacular Indian History, Economics, Land Tenure, and Religions-all courses at the School of Oriental Studies inaugurated by the university in 1883. The best university men, some of them Indian, were to be chosen through rigorous tests, which as a member of the Committee on Examinations, Jowett helped prepare.

Jowett once confided to his longtime friend and confidante Florence Nightingale, "I should like to govern the world through my pupils." He made an impressive start. Those who passed the ICS examinations were obliged to attend a university for a probationary two years. Jowett offered a place at Balliol to each successful candidate ("poaching," his academic rivals snorted) and provided all entrants with a special tutor (Arnold Toynbee, uncle of the noted historian). Consequently more than half the probationers chose Oxford in the 1890's, compared with Cambridge's twenty percent. According to Richard Symonds's tally in Oxford and Empire (1986)1 600 of 2,200 Balliol matriculates from 1875 to 1914 obtained imperial posts, half in the Indian services. Within Britain, Balliol accounted for more than forty seats in the House of Commons -- and for seventeen years, from 1888 to 1905, three successive Viceroys of India were Jowett's pupils.

It was a heady triumph for The Jowler, Oxford, and Plato. Indeed there was a striking likeness between the Platonic prescription and India, where the British hierarchy replicated that in The Republic: Guardians at the peak, the warriors next, followed by merchants and Other Ranks at the bottom. As remarked by Philip Mason in The Men Who Ruled India (1954), the four basic Hindu castes -- sages, warriors, traders, and menials -- likewise corresponded with this pyramid. Mason, a Balliol man who served twenty years in the Indian Civil Service, notes that the British Guardians were a caste apart from those they ruled. They were forbidden to own land or engage in trade, and were governed by their elders-all this "on exactly Plato's principles." In India as in Plato's ideal state, the military was subordinate to the civil, but (as in The Republic), some of the ablest officers could be chosen for the Political Department and thus rise into the ranks of the Guardians.

A fine scheme, but with a palpable catch. As with Plato, Jowett's focus was on good government rather than self-government. The Raj was a paternalist autocracy imposed by an alien race, and while its admirers made much of its good works -- schools, courts, hospitals, roads, irrigation -- little was said about consent of the governed. Jowett himself believed qualified Indians should be represented in the highest councils. Yet progress towards bureaucratic power sharing, much less elective government, was glacial, slowed by the hostility of lower-status Europeans. As for Curzon, his inability, or rather unwillingness, to reconcile efficiency and democracy proved his undoing in what would be the last classic imperial adventure, the British invasion of Tibet.

"THERE IS MORE GREAT AND PERMANENT GOOD TO BE DONE IN India than in any department of administration in England," Jowett wrote to Lord Lansdowne, the first of his three pupils to accept the Viceroyalty. In that spirit, Curzon grasped the same reins. He had now completed his great voyages, gained valuable experience as parliamentary Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs to Lord Salisbury and secured his financial independence with an interesting match. In 1895 he married Mary Victoria Leiter, whose father founded the Chicago dry-goods emporium that became Marshall Field. "Of family, as the word is here understood," sniffed The Times of London some years later, "he had none; of position, none save that which he created for himself." Yet his daughter was to occupy (as her biographer Nigel Nicolson observes) the most splendid position that any American, man or woman, held in the British Empire.

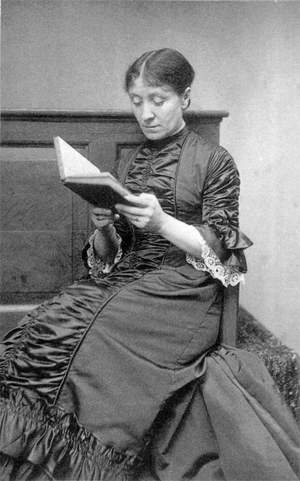

Mary's face complemented her father's fortune (reckoned by Nicolson at $20 million in 1890's dollars). At five-foot-eight, with her wisp of a waist and captivating gaze, she was the belle of every ball after her debut in Washington, where the first Englishman to propose to her was Cecil Spring Rice of the British Legation, co-scribbler of the Oxford "superior person" doggerel. At a London ball in 1890, she met George Curzon. Both were smitten. There followed a protracted, on-again, off-again long-distance courtship that survived his sending texts of his speeches instead of billets-doux. He finally proposed in 1893 but insisted their engagement be kept secret for two years so he could visit Afghanistan, "my last wild cry of freedom." The wedding was in Washington, the marriage successful. Mary was self-assured and sweet-tempered, and when George accepted the Vice-royalty, she passed inspection at Windsor by the Queen Empress, who informed Curzon his wife was "wise and beautiful."

Having settled in Calcutta at Government House (whose design, auspiciously, was inspired by Kedleston), the new Viceroy made clear that he was not going to be a Great Ornamental, the phrase applied to his sedate predecessor, Lord Elgin. Curzon plunged into his work, assaying such diverse questions as creating a new North-West Frontier Province, coping with a threatened famine by a timely visit to Gujerat (the rains came along with him, confirming belief in his miraculous powers), founding a steel industry, launching a Directorate of Criminal Intelligence, stabilizing finances and currencies, and always riding herd on a bureaucracy that he faulted as dilatory. He hated the system of circulating endless minutes among departmental chiefs: "All these gentlemen state their worthless views at equal length, and the result is a sort of literary Bedlam." "Efficiency of administration," he admonished, "is a synonym for contentment of the governed."

Curzon took personal charge of the Foreign Department, whose policies were of keenest interest to him, involving as they did relations with Russia, China, Persia and the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and -- a recent and exasperating item -- Tibet. It appeared that the Tibetans had trespassed into British-ruled Sikkim, demolishing boundary pillars. They also obstructed compliance with the Anglo-Tibetan Convention of 1890 and the ancillary Trade Regulations of 1893, providing inter alia for the establishment of a British trading mart within Tibet. To these injuries was added insult when the boyish Thirteenth Dalai Lama returned, apparently unopened, urgent missives from the Viceroy that had been delivered by a Bhutanese landowner named Ugyen Kazi. Or so Curzon had been told. Later, he doubted whether Kazi had ever reached Lhasa or was to be trusted at all.

Adding to his perplexity was a dispatch in October 1900 from the British charge in St. Petersburg. Enclosed was an item from a Russian newspaper reporting that Nicholas II had at his palace in Yalta received Agvan Dorzhiev, described as the "first Tsanit Hamba to the Dalai Lama of Tibet." "I have not been able, so far," the charge added, "to procure any precise information with regard to this person or to the mission on which he is supposed to come to Russia." Curzon shrugged at first. He then learned that Dorzhiev was a Russian Buriat who passed through India under the noses of Bengal police, his presence unreported by the same native agents, Sarat Chandra Das, Lama Ugyen Gyatso, and the Abbot Sherab Gyatso, on whom Curzon relied for intelligence on Tibet. The cumulative effect was to change the Viceroy's stance on Tibet from "patient waiting" to "impatient hurry."

This sense of urgency was rooted in Curzon's long-held belief that Russia's ultimate ambition was dominion of Asia. "It is a proud and not ignoble aim, and it is worthy of the supreme and material efforts of a vigorous nation," he observed in a 1901 Minute. Yet if Russia were entitled to her aims, "still more so is Britain entitled, nay compelled, to defend that which she has won, and to resist the minor encroachments which are only part of the larger plan." Piecemeal concessions were to be shunned, he maintained, since each morsel "but whets the appetite for more, and inflames the passion for a pan- Asiatic dominion." Curzon's fears were quickened by events in China: the chaos in Peking during the Boxer Rebellion, the steady Russian penetration of Mongolia and Manchuria, and the likelihood (as speculated by George McCartney, the British watchdog in Kashgar) that Russia would next devour Chinese Turkestan, bringing Cossacks to the very borders of Tibet.

That Russia might invade India or its neighbors was scarcely farfetched to Curzon, who was quick to recall that Napoleon and two Tsars -- Paul and Alexander I -- seriously discussed a joint assault. Such an operation was now more feasible because Russia was at India's doorstep and could speed troops across the steppe by rail. In 1888, Curzon had been among the first foreigners to book passage on Russia's new Trans-Caspian Railway, and saw for himself the alarming mobility made possible by steam and steel. The Russians themselves advertised these possibilities. Curzon noted in Russia in Central Asia (1889): "General Prjevalski, in one of his latest letters, dated from Samarkand only a month before my visit to Transcaspia, recorded his opinion of the line, over which he had just travelled, in these words: 'Altogether the railway is a bold undertaking, if great significance, especially from the military point if view in the future'" (Curzon's italics).

So what should be done regarding Tibet? The Viceroy advised his superiors in London to bypass China, whose claims of suzerainty over Tibet were a "farce." British dealings "must be with Tibet and Tibet alone." It was essential "that no-one else should seize it, and that it should be turned into a sort of buffer state between the Russian and the Indian Empires." Soon enough, he warned the Secretary of State for India, Lord George Hamilton, "steps" might be required "for the adequate safeguarding of British interests upon a part of the frontier where they have never hitherto been impugned." Hamilton's response -- this was July 1901, when Britain was already mired in the Boer War -- cautioned that consultation was essential before taking "steps." "Strong measures," however justified, "would be viewed with much disquietude and suspicion."

Curzon bided his time. In 1902-3, circumstances played into his willing hands, and his Tibetan project became inextricably associated with its chief executor, Francis Edward Younghusband (1863-1942).

SOLEMNLY GOOD-LOOKING, YOUNGHUSBAND GAZES FROM UNDER imposing brows from his page in imperial history. The Dictionary of National Biography describes him as "soldier, diplomatist, explorer, geographer, and mystic," much the sort of fellow who might appeal to Curzon, as he did when they first met in 1894. Fittingly, the venue was Chitral, a lofty kingdom on the far edge of India's North-West Frontier, where Captain Younghusband was Political Officer. Curzon's irritating certitude, his House of Commons debating manner, grated at first, but the young officer soon discerned other qualities: warmth, tenderness, loyalty, and political views that matched his own.

Younghusband was the frontiersman's frontiersman. Born in the Indian hill town of Murree, he was a son of an Indian Army general and a nephew of the explorer Robert Shaw, the first Briton known to cross the Himalayas to Yarkand and Kashgar. In a familiar rite of passage, young Francis returned to England for schooling at Clifton and Sandhurst, winning a Guards commission. Once back in India, he embarked on missions that took him from the Indus to the Afghan border; from Kashmir to Kulu; then in a great arc from Manchuria's Long White Mountain to Peking and across the Gobi Desert. His transit of China, and his explorations of the High Pamirs and the Karakorum, won him the Founder's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society (1890), resulted in a well-received book (The Heart of a Continent, 1896), and led to memorable encounters on two occasions with Tsarist officers scouting the nebulous boundaries of the British, Russian, and Chinese empires. Meeting with Colonel Grombtchevski in the High Pamirs, he posed for photographs and debated with him in French on the logistics of invading India. Then ungallantly, he misled the Russian about nearby passes, recommending a route "leading from nowhere to nowhere," without grass or fuel. When Colonel Yanov, after equally friendly libations, ordered Younghusband to leave "Russian territory," the Briton did so under protest, yielding only because he lacked an escort and faced thirty Cossacks. There were no hard feelings; Yanov pressed a gift of venison and apologized for being required to behave like a policeman. An official apology later followed from the Russian Foreign Minister for what was said to be a misunderstanding.

At Chitral on the North-West Frontier in 1893-94, under arrangements possible then, Younghusband was granted a leave of absence to report for The Times of London on a campaign by the legendary Guides (in which his brother George was an officer). A dynastic war was underway among Chitrali claimants to the throne; Russian meddling was suspected, and a British unit was under siege at a remote fort. Two relief columns were mobilized, one marching from Peshawar, the other from Gilgit. Against the odds both survived punishing passes, lifted the siege, and left the fort with a reinforced garrison. Younghusband recounted this for The Times and more fully in a book (co-authored with his brother). It was during this campaign that he met Curzon, who on returning to Britain used his firsthand authority to persuade the Government to hang on to the Chitral fortress lest the Russians take it first (which, it became known later, they planned to do).

At this time, something else important happened to Younghusband. At Chitral, he read The Kingdom of God Is Within You by another former frontier officer with a mystical temper, Leo Tolstoy. "It has influenced me profoundly," he wrote in his diary. " ... I now thoroughly see the truth of Tolstoi's argument that Government, capital and private property are evils. We ought to devote ourselves to carrying out Christ's sayings, to love one another (not engage in wars and preparations for wars) and not resist evil with evil." Tolstoy did not explain how all this could be done, Younghusband added, but said a few great ones, like Columbus, must find the way: "And this is what I mean to do."

Thereafter Younghusband the spiritual explorer cohabited with Younghusband the martial imperialist, a curious joint pilgrimage with many odd detours. Certainly Tolstoy did not deter him from obtaining an extended leave to travel to southern Africa, where, as a Times correspondent, he again sang the praises of Pax Britannica. There he met Cecil Rhodes, visited Rhodesia, and was present in Johannesburg at the time of the Jameson Raid, the botched attempt to stir an uprising against the Boers. Younghusband evidently knew of the raid beforehand, and seemingly approved the operation in collusion with Flora Shaw, the newspaper's Chief Colonial Correspondent. At a dramatic public inquiry on the affair in London, Miss Shaw artfully managed to protect both the newspaper and Younghusband from charges of complicity in a rash act of war.

The fuss subsided and Younghusband returned to India, where his superiors took him down several pegs by posting him as Resident in Indore, not a very challenging or visible assignment. He wrote in discouragement to Curzon in August 1901 asking whether he should resign from the Indian Political Department. "I have always had the ambition to work at the great main questions of Asiatic Policy," he said, "and it is to these that I now wish to turn my undivided attention." At around this time, the Viceroy -- who advised him to stay put for the moment -- knew he had found the right man to lead a mission to Tibet.

IN 1902, MIDWAY IN HIS FIVE-YEAR TERM, CURZON PERSUADED A doubtful Cabinet in London to authorize a Coronation Durbar for Edward VII. Not only was the Durbar an accepted feature of Indian life, he contended, but it would be "an act of supreme public solemnity" demonstrating the Raj's unity and strength. It was to take place in Delhi, seat of the old Mughal Empire, in January 1903, its pageantry more "Indo-Saracenic" than "Victorian Feudal," with Curzon himself as impresario. "You talked about stage management," Curzon confided to a friend in London. "That is just what I am doing for the biggest show that India will ever have had." The Coronation Durbar reflected not only Curzon's love of pomp but his heartfelt belief that the "Oriental mind" thrived on spectacle. On a famous occasion years before, he turned up for an audience with the Emir of Afghanistan wearing medals and decorations purchased from a theatrical costume shop. As it transpired, in the event at what people called the "Curzonization," a million or so onlookers had plenty that was genuine to gape at. Column upon column of heralds and dragoons, plus veterans of the Mutiny, preceded the Viceroy and Vicereine, borne aloft on a silver howdah. Next in the elephant procession were the Duke and Duchess of Connaught, representing the Crown, leading fifty Indian princes, in exact order of precedence. As The Times correspondent (one of a pampered brigade of journalists) wrote, the effect was like "a succession of waves of brilliant colour, breaking into foams of gold and silver, and the crest of each wave flashed with diamonds, rubies and emeralds of jewelled robes and turbans, stiff with pearls and glittering with aigrettes." At the climactic State Ball, four thousand breaths stopped as the Viceregal couple entered, he in his white satin knee breeches, she in her instantly celebrated dress, fashioned of cloth-of-gold encrusted with emeralds in the pattern of peacock feathers. For Curzon, it was a gratifying success, the only serious blemish being his home Government's refusal to let him announce -- in the fashion of Oriental potentates -- a reduction in salt taxes (he was allowed only to hint vaguely at "measures of financial relief").