Part 1 of 7

A Sketch of the History of the Indian Press, During the Last Ten Years: With a Biographical Account of Mr. James Silk Buckinghamby Sandford Arnot

Member of the Asiatic Society of Paris

Second Edition

1830

“Is it British justice, for the faults imputed to one man to punish millions?

-- Memorial of the Natives of India to the King of England.

Contents:• Errata

• To the Conductors of the Public Press of Great Britain

• History of the British Press in India, viz.

• I. During the Administration of the Marquis of Hastings

• II. Under the Administration of the Hon. John Adam

• III. Under the Government of Lord Amherst

• Proceedings in England Connected with the Indian Press

• Discovery of reason to believe that Mr. B. had abstracted nearly £10,000 from the cause of the Indian Press

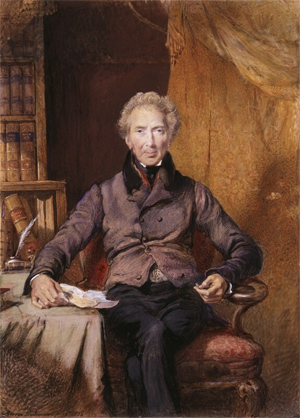

• Biographical sketch of Mr. James Silk Buckingham

• Causes of this Publication connected with the above Discovery

• Suppressed Defence of Mr. Arnot against the Calumnies invented by Mr. J.S. Buckingham, in revenge for the above Discovery

• Apology for him by his Agents in India, not denying the charge

• Reply to the same by "NO DUPE", maintaining it as proved

• Remarks on the Apology, showing its weakness

• History of his conduct to Mr. St. John, his literary Coadjutor in England

• Mr. Buckingham as an Itinerant Orator

• Peter the Hermit's Cave -- Description of the alleged "obscure Lodgings in the outskirts of London," to which the soi-disant [Google translate: Supposedly] Patriot and Martyr, "Peter the Hermit," retired to "drink the chrystal stream," as given out, while soliciting charitable relief, by boards pasted up all over London, begging for the smallest pittance to alleviate his distress

• Proofs and Illustrations, and Catalogue of Mr. B.'s Contradictions, being an Analysis of printed Notarial Documents annexed

ERRATA

Page / Line14 / 15 / For “before," read “for. "

15 / 25 / For £4,500, read £4,000.

18 / 17 / For Sir, read Mr.

19 / 21 / For “ Shewing,” read “ Knowing."

-- / 22 / After which, read "at."

22 / 31 / For "Turlon," read "Turton."

30 / 1 / For "persons," read "previous."

59 / last line, / After "know" omit the semicolon.

80 /40 / For £500, read £1050.

To the Conductors of the Public Press of Great BritainI know not to whom I can so appropriately dedicate the following brief history of the Indian Press, during the last ten years, as to you who have nourished it from your inexhaustible intellectual stores, stimulated it by your example, and sympathised in its misfortunes. The account of these you will not read with the less interest, that the author of it was him self a participator in the events which he describes; and may, therefore, with justice say in the words of the ancient: quæque miserrima vidi, et quorum pars fui. [Google translate: I saw the most miserable, the Jews established, and of which I was a part of.]

2, South Crescent,

Bedford Square.

HISTORY OF THE BRITISH INDIAN PRESS.

I. DURING THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE MARQUIS OF HASTINGS.As the publication of the following statement of facts arose out of circumstances beyond my control, I claim no merit in bringing it before the world. All that remains in my power is to render the publication as subservient as possible to the public good, and to the cause of truth, by accompanying it with such explanations as will place in a true light an important question with which it is connected.

It is, indeed, the duty of every man who has suffered in a public cause, to embrace every fair opportunity of stating to the world his reasons for supporting it and the dangers to which it is exposed, either from professed friends or open foes. No phrase is more commonly in every one's mouth than that the character of public men is public "property." If so, it is the duty of the public to ascertain with the greatest care what that character is, that they may know whether or not their property be a good one, and the tenure by which they hold it secure. It is, above all, the duty of those who are friendly to the same cause, to ascertain that they entrust its advocacy into the most trustworthy hands: for surely no wise people engaged in any contest would entrust the command of an important post to a person of whose honesty they were not perfectly secure; or, to come to more every-day transactions, no prudent merchant would leave his vessel in charge of a pilot, however expert and daring, if there was reason to apprehend that, from want of principle and to serve his own purposes, the pilot would run the vessel upon the rocks.

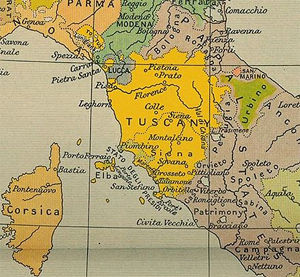

Just so has the cause of the Indian Press been already shipwrecked; and it is my painful duty to describe by whom, and by what means, it has been ruined: ruined for a time, at least; and if it should ever recover that shock, the best service I can render it is by a faithful account of the causes of its past misfortunes, to guard its friends against similar dangers in future. Ten years ago the censorship had been abolished by the Marquis of Hastings, the then Governor General of India. After he had concluded victoriously two important wars, and secured the country from foreign aggression and internal pillage, thereby placing the hundred millions under his sway in tranquillity and peace, to improve their condition still more, he gave them a press, through which they might explain their wants and wishes, free from the control of a censor. This act was applauded all over the East, and hailed as the commencement of a new and glorious era in India, as shewn by the address presented to his Lordship by "about five-hundred of the most enlightened Gentlemen of Madras," who manfully raised their voices in its favour, notwithstanding the Government of that Presidency was adverse to the measure. (Vide the Hon. Col. Stanhope's History of the Indian Press, p.82). These five hundred included the chief justice and judges, and law officers of his Majesty's Supreme Court for British law, the chief judge of the Company's Supreme Court for native law (Sudder Adawlut), the residents of Hyderabad and Nagpore, and the Company's principal Staff Officers, &c. &c. &c., men of as high rank and influence in that part of the world, as the ministers and members of the British Cabinet are in England. Nor was the measure without its powerful friends even in this country: what Lord Hastings had done in the East, there was here the immortal eloquence of a Canning ready to defend.

In less than four years from the brilliant period of which I have been speaking, all this had passed away like a refreshing summer cloud, and not a shadow of freedom was left to any press in India. A measure was enacted to silence public discussion, by placing all newspaper property at the mercy of the Government. No public meeting was called, and hardly ten voices were raised in all India against this measure; and when it was afterwards discussed in the Court of East-India Proprietors, the only public body in England likely to take a deep interest in the question, a body, too, into which every liberal man in England, possessed of property, may, if he chooses, enter and declare his sentiments, so low was the cause of the freedom of the Indian Press sunk, that at last hardly three hands were raised in its behalf!

What produced this remarkable and melancholy change? The opponents of the freedom of discussion in India attribute it to the badness of the cause itself; I, however, am prepared to prove that it arose from the lamentable conduct of a person who put himself forward as its advocate, and continued to pervert the energies of the Press to his own selfish purposes, by converting it into an instrument of gratifying his personal piques and vanity, and of levying contributions on the public. This, at least, is the judgment which I have formed, on an extent of experience and knowledge of the subject which few besides myself have had an opportunity to acquire. But the contents of the following pages will enable every reader to judge for himself; and, if I succeed in proving the justness of my opinion, it may be the means of rescuing the cause of the Indian Press from the obloquy which has been brought upon it by the misconduct of its professed friend and advocate: it may be the means of again obtaining for the principle of free discussion, as applied to India, a patient and impartial consideration at the approaching investigation regarding the best mode of governing that important division of the British Empire.The Marquis of Hastings having been the great founder and patron of the freedom of the Press which existed in India, it is the duty of every friend to that measure to place his character and policy in their just point of view. His new regulation for the Press, dated the 12th of August 1819, which abolished the censorship, was to the following effect, viz.

That Editors of newspapers were prohibited from publishing, 1st. Animadversions on the measures of public authorities in England connected with the Government of India, or on the local administration, the Members of Council, Judges of the Supreme Court, or the Lord Bishop of Calcutta. 2dly, Any thing calculated to excite alarm or suspicion amongst the natives as to any intended interference with their religion. 3dly, Private scandal or personal remarks tending to excite dissention in society.

The consequence that would result from an infraction of these restrictions was stated in these words:

"Relying on the prudence and discretion of the Editors for their careful observance of these rules, the Governor General in Council is pleased to dispense with their submitting their papers to an officer of Government previous to publication. The Editors will, however, be held personally responsible for whatever they may publish in contravention of the rules now communicated, OR which may be otherwise at variance with the general principles of British law as established in this country, and will be proceeded against in such manner as the Governor General in Council may deem applicable to the nature of the offence, for any deviation from them."

Here two classes of offences are clearly pointed out; one class, offences against British law; another class, offences against the rules now laid down for the press. For the first class, the Government might proceed by an action at law in the usual form; for the second, it evidently could not, because they were rules unknown to that law. Some other mode of enforcing them must, therefore, have been in contemplation, or the enactment of Regulations, which there was no power to enforce, would have been an act of mere folly. But the Governor General of India is vested with a power of ordering any British subject (if a native of the United Kingdom) to quit India, and by this power a British editor who resisted the authority of these rules might, consequently, be punished by expulsion from the country. Therefore, in enacting these rules beyond the letter of the law, and announcing that any Editor disregarding them would be "proceeded against," Lord Hastings clearly announced (and could have meant nothing else) that he would exercise the power of "summary transportation without trial," when necessary, as a means of coercing the conductors of the Indian Press, and enforcing the above restrictions after the abolition of the censorship. This is the true character of the act for which he received the applauses of the five hundred enlightened and distinguished residents of Madras, to which he is stated to have returned the following memorable, thousand-times quoted, reply:--

"My removal of restrictions from the Press," (by which his Lordship clearly meant the censorship, a most galling restriction, which he had removed for something far less grievous), "has been mentioned in laudatory language. I might easily have adopted that procedure without any length of cautious consideration, from my habit of regarding the freedom of publication as a natural right of my fellow subjects, to be narrowed only by special and urgent cause assigned. The seeing no direct necessity for these invidious shackles might have sufficed to make me break them. I know myself, however, to have been guided in the step by a positive and well-weighed policy. If our motives of action are worthy, it must be wise to render them intelligible throughout an empire, our hold on which is opinion. Further, it is salutary for supreme authority, even when its intentions are most pure, to look to the control of public scrutiny. While conscious of rectitude, that authority can lose nothing of its strength by its exposure to general comment: on the contrary, it acquires incalculable addition of force.

That Government which has nothing to disguise, wields the most powerful instrument that can appertain to sovereign rule. It carries with it the united reliance and effort of the whole mass of the governed: and let the triumph of our beloved country in its awful contest with tyrant-ridden France speak the value of a spirit, to be found only in men accustomed to indulge and express their honest sentiments."

Previous to this, under the Censorship, no one had the power of publishing any sentiment, however honest, except what the censor pleased to permit: whereas, under Lord Hastings's new regulation, every one had the power of saying everything, as in England, subject only to punishment afterwards, if he contravened the laws or regulations. By the former, the liberty of the press is to this day narrowed in England; by the latter, it was still farther narrowed in India: and to this his Lordship must have alluded, in saying that it was to be narrowed "only by special and urgent cause assigned."

The motives for these limitations on the freedom of discussion may be easily perceived. Censures passed on the Court of Directors, or other public authorities in England, might be supposed incapable of influencing men at such a distance, who, most probably, would never see or read them, or of altering measures already passed; while they might excite a local ferment and opposition abroad, where it could be of no avail, and thereby create alarm at home, and raise up powerful enemies to the very freedom of discussion which the Noble Marquis was so desirous to establish. The same reasoning might be applied to animadversions on the Lord Bishop of Calcutta, Members of Council, Judges of the Supreme Court, &c., viz. that the Press might sting and wound the feelings, but, in the present state of society in India, where so few are independent, could not exercise an efficient control over persons holding the highest rank and authority. Would it be wise, then, to begin by making enemies of those whose opposition might so soon prove fatal to an institution yet in its infancy.* [Vide the Hon, Col. Stanhope's History, p. 54.]

Lord Hastings knew that the far-famed Press of England did not attain to its present strength and importance in a day, nor in a century. By prudent and moderate management, he saw that the Press of India might also be gradually nursed into maturity; that the alarms felt on account of its novelty would subside, the benefits of its operation be experienced, and men's minds, by degrees, become accustomed to its controul.

It is lamentable to think that a scheme so full of hope and promise, so enlightened and beneficent, could be thwarted by the turbulent conduct of one man. But,"The reckless hand which fired th' Ephesian dome,

Outlives in fame the pious sage that raised it,"

and the firebrand, in the present case, was Mr. James Silk Buckingham. No difficult matter was it to excite a flame, if any one was found so imprudent or unprincipled as to apply the torch of discord: for the experiment of introducing freedom of discussion among a hundred millions of Asiatics, was, of itself, of a nature to excite distrust, if not alarm, in the minds of the many whose principle of policy it is to hold fast by that which is established and shun all innovation.

Mr. Buckingham, who conducted a Paper called the "Calcutta Journal," began by extolling the Marquis of Hastings, his character and government, in such terms of adulation, as to excite first jealousy and ultimately disgust; since others, holding a less prominent place in the administration, might justly feel that they had as much merit in the measures adopted as its head, on whom these praises were so extravagantly lavished. From this he gradually proceeded in his praises more pointedly to contra-distinguish the noble Marquis from the rest of the administration, which Mr. B. now taught the public to view as consisting of a good and an evil principle; Lord Hastings representing the former, and his Council, Secretaries, &c. the latter. This personal court to the great man might serve a temporary purpose. Mr. Buckingham, it has since been stated, was then making interest for a situation under the Government. He did not succeed in his object; perhaps the flattery was too gross for the refined sentiments of Lord Hastings. But these crafty artifices did not fail to excite jealousy between him and his Council and official advisers; and these latter being the most permanent elements of the government, who rise successively into power as its heads drop off, their opposition to Lord Hastings' policy, in the end, proved fatal to the liberty of the Press.They seem to have said to themselves:

"Is any lord or lordling from England to come and reap the benefit of our long-earned experience, and then set up a sycophant to flatter himself as the author of every good thing done, and sneer at us, who have borne the burden and heat of the day, as insignificant underlings?"

The manner in which Mr. Buckingham contrived to create enemies to the freedom of the Press in other quarters, will be best shewn by a brief summary, accompanied with a few extracts from his correspondence with the Government, as published by himself.

1stly. Attack on the highest law authority in India. -- The feelings of his Majesty's Chief Justice were deeply wounded by a severe animadversion on a transaction, necessarily of a very distressing kind to him, which occurred in his family, allusion to which in a public newspaper was the leas called for, as the affair was of a domestic and private, not of a public or political character; and the less excusable, as the affair, having happened, was such as no censure or regret could remedy or recal. No journalist, therefore, was justified in laying hold of such an opportunity to wound the feelings of a father; and by personal injury, probably render hostile to the Press a person who might have been its most powerful friend, from holding the highest legal office in India. Sir Edward Hyde East had notwithstanding the virtue to speak in favour of the liberty of the Press, if properly used, when it came afterwards under discussion in a case wherein Mr. Buckingham himself was the defendant. His successor in authority, however, avenged his cause by sealing its destruction.

2dly. Attack on the Governor of Madras. On the 18th of June 1819, the Lord Hastings caused the following letter to be addressed to Mr. Buckingham, respecting an attack on Governor Elliott:

Sir, 1. The attention of Government having been drawn to certain paragraphs, published in the Calcutta Journal of Wednesday the 26th ult. I am directed by his Excellency the Most Noble the Governor General in Council, to communicate to you the following remarks regarding them.

2. The paragraphs in question are as follows:-- "Madras. We have received a letter from Madras of the 10th instant, written on deep black-edged mourning post, of considerable breadth, and apparently made for the occasion, communicating, as a piece of melancholy and afflicting intelligence, the fact of Mr. Elliott's being confirmed in the government of that Presidency for three years longer!! It is regarded at Madras as a public calamity, and we fear that it will be viewed in no other light throughout India generally. An anecdote is mentioned in the same letter, regarding the exercise of the censorship of the press, which is worthy of being recorded, as a fact illustrative of the callosity to which the human heart may arrive; and it may be useful, humiliating as it is to the pride of our species, to show what men, by giving loose to the principles of despotism over their fellows, may at length arrive at."

[Then, after stating that the Censor there had prevented the publication of a letter from the Princess Charlotte to her mother, Mr. Buckingham concluded by saying] "that it tended to criminate, by inference, those who were accessory to their unnatural separation, of which party the friends of the DIRECTOR of the Censor of the Press unfortunately were!

3. The Governor General in Council observes that this publication is a wanton attack upon the Governor of the Presidency of Fort St. George, in which his continuance in office is represented as a public calamity, and his conduct in administration asserted to be governed by despotic principles and influenced by unworthy motives.

4. The Governor General in Council refrains from enlarging upon the injurious effect which publications of such a nature are calculated to produce in the due administration of the affairs of this country. It is sufficient to inform you that he considers the paragraphs above quoted to be highly offensive and objectionable in themselves, and to amount to a violation of the obvious spirit of the instructions communicated to the Editors of newspapers, at the period when this Government was pleased to permit the publication of newspapers, without subjecting them to the previous revisions of the officers of Government.

5. The Governor General in Council regrets to observe, that this is not the only instance in which the Calcutta Journal has contained publications at variance with the spirit of the instructions above referred to. On the present occasion, the Governor General in Council does not propose to exercise the powers vested in him by law; but I am directed to acquaint you, that by any repetition or a similar offence, you will be considered to have forfeited all claim to the countenance and protection of this Government, and will subject yourself to be proceeded against under the 36th section of the 53d Geo. III., cap. 155."

To this letter from Lord Hastings his magnanimous and liberal protector, Mr. Buckingham, in reply, concluded with the following sentence:

"The very marked indulgence which his Lordship in Council is pleased to exercise towards me, in remitting on this occasion the exercise of the powers vested in him by law, will operate as an additional incentive to my future observance of the spirit of the instructions issued before the commencement of the Calcutta Journal, to the editors of the public prints of India, in August 1818, of which I am now fully informed, and which I shall henceforth make my guide."

The next attack on the same Government of Madras related to the transmission of his journal by post, which Mr. Buckingham insinuated was impeded in that presidency by the Government, from hostility to its principles. On this Lord Hastings thus commented, in an official letter dated January 12th 1820:

"2. The observations alluded to are clearly intended to convey the impression that the Government of Fort St. George had taken measures to impede the circulation of the Calcutta Journal, which measures were unjust in themselves, and originated in improper motives.

"5. Your remarks on the proceedings of the Government of Fort St. George are obviously in violation of the spirit of those rules to which your particular attention, as the Editor of the Calcutta Journal, has been before called; and the unfounded insinuations conveyed in those remarks greatly aggravate the impropriety of your conduct on this occasion.

"6. The Governor General in Council has perceived with regret the little impression made on you by the indulgence you have already experienced; and I am directed to warn you of the certain consequence of your again incurring the displeasure of Government. In the present instance, his Lordship in Council contents himself with requiring, that a distinct acknowledgment of the impropriety of your conduct, and a full and sufficient apology to the Government of Fort St. George, for the injurious insinuations inserted in your paper of yesterday, with regard to the conduct of that Government, be published in the Calcutta Journal."

In reply, Mr. Buckingham informed Lord Hastings that as he had received an address from Madras complimenting him on his abolition of the Censorship, by the substitution of the more lenient restrictions before mentioned, to which he had replied as above quoted, therefore he (Mr. B.) considered these restrictions as no longer existing!

"I conceived," he says, "that the regulations or restrictions of August 1818, were as formally and effectually abrogated by that step (the reply to the address) as one law becomes repealed by the creation of another, whose provisions and enactions are at variance with the spirit of the former."

This was, in fact, to maintain that an Act of Parliament or an order in Council might be annulled by a speech of the Duke of Wellington at Apsley House, or the City of London Tavern: and that a speech, too, which declared that the liberty of the Press was to be "limited by special cause assigned," must be held to signify and declare, that this liberty was to be quite unlimited! On these grounds the Marquess of Hastings was most disingenuously and ungratefully accused of professing one thing and meaning another. His Lordship, however, magnanimously passed over the imputation on himself, and rested satisfied with an apology being published by Mr. Buckingham, expressing his regret at "having worded the original notice so carelessly as to bear the appearance of disrespectful notice on the Governor of Madras."

3dly. Attack on the highest ecclesiastical authority, the Lord Bishop of Calcutta. This was published on the 10th July 1821, as follows:--

"It is asserted (but I conceive erroneously) that the Chaplains have received orders from the Lord Bishop of Calcutta, not to make themselves amenable to any military or other local authorities; and, therefore, when a young couple at an outpost prefer going to the expense of making the clergyman travel 250 miles to go and marry them, he is at perfect liberty to accept the invitation, and to leave 3000 other Christians, his own parishioners, to bury each other, and postpone all other christian ordinances until his tour is completed, which, in this instance, occupies, I understand, more than three sabbaths.

In consequence of one of these ill-timed matrimonial requisitions in December last, the performance of divine service, and other religious observances of the season, were entirely overlooked at Christmas, which passed by for some Sundays in succession, and Christmas-day included, wholly unobserved,

It would appear, therefore, to be highly expedient, that no Military Chaplain should have the option of quitting the duties of his station, from any misplaced power vested in him by the Lord Bishop, unless he can also obtain the express written permission of the local authorities on the spot to do so, and provided, in all such cases, the season is healthy, and no one dangerously ill, and that he shall unerringly return to the station before the Sunday following, that divine service may never be omitted in consequence of such requisition."

On the name of the author of this statement being asked for by the Government, Mr. Buckingham replied that he did not know any thing about him, as it was anonymous, but that he thought publishing it might be productive of good. To this Lord Hastings sent the following reply:

"It was to have been hoped, that when your attention was called to the nature of the publication in question, you would have felt regret at not having perceived its tendency, and that you would have expressed concern at having unwarily given circulation to a statement which advanced the invidious supposition that the Bishop might have allowed to the Chaplains a latitude for deserting their clerical duties, and disregarding the claims of humanity.

Instead of manifesting any such sentiment, you defend your procedure, by professing that you 'published the letter under the conviction, that a temperate and modest discussion of the inconveniences likely to arise from a want of local control, in certain points, over Military Chaplains, might be productive of public benefit.'

It is gross prostitution of terms to represent as a temperate and modest discussion an anonymous crimination of an individual, involving at the same time an insinuated charge, not the less offensive for being hypothetically put, that his superior might have countenanced the delinquency.

With these particulars before your eyes, and in contempt of former warnings, you did not hesitate to insert in your Journal such a statement from a person of whom you declare yourself to be utterly ignorant, and of whose veracity you consequently could form no opinion. Your defence for so doing is not rested on the merits of the special case. But as your argument must embrace all publications of a corresponding nature, you insist on your right of making your Journal the channel for that species of indirect attack upon character in all instances of a parallel nature.

When certain irksome restraints, which had long existed upon the press in Bengal, were withdrawn, the prospect was indulged that the diffusion of various information, with the able comments which it would call forth, might be extremely useful to all classes of our countrymen in public employment. A paper conducted with temper and ability, on the principles professed by you at the outset of your undertaking, was eminently calculated to forward this view. The just expectations of Government have not been answered. Whatsoever advantages have been attained, they have been overbalanced by the mischief of acrimonious dissensions, spread through the medium of your Journal. Complaint upon complaint is constantly harrassing Government, regarding the impeachment which your loose publications cause to be inferred against individuals. As far as could be reconciled with duty, Government has endeavoured to shut its eyes on what it wished to consider thoughtless aberrations, though perfectly sensible of the practical objections which attends these irregular appeals to the public. Even if the matter submitted be correct, the public can afford no relief, while a communication to the constituted authorities would effect sure redress; yet the idleness of recurrence to a wrong quarter is not all that is reprehensible, for that recurrence is to furnish the dishonest conclusion of sloth or indifference in those bound to watch over such points of the general interest. Still the Government wished to overlook minor editorial inaccuracies. The subject has a different complexion when you, Sir, stand forth to vindicate the principle of such appeals, whatsoever slander upon individuals they may involve, and when you maintain the privilege of lending yourself to be the instrument of any unknown calumniator. Government will not tolerate so mischievous an abuse. It would be with undissembled regret that the Governor General in Council should find himself constrained to exercise the chastening power vested in him; nevertheless he will not shrink from its exertion, where he may be conscientiously satisfied that the preservation of decency and the comfort of society, required it to be applied. I am thence, Sir, instructed to give you this intimation: should Government observe that you persevere in acting on the principle which you have now asserted, there will be no previous discussion of any case in which you may be judged to have violated those laws of moral candour and essential justice, which are equally binding on all descriptions of the community. You will at once be apprized that your license to reside in India is annulled, and you will be required to furnish security for your quitting the country by the earliest convenient opportunity."

From the indignant tone of this letter, and the expressions with which it concludes, respecting the necessity of adhering to the laws of "moral candour and essential justice," it is plain that Lord Hastings now had become convinced that he had been trifled with, by promises never meant to be fulfilled, and that his liberal and generous forbearance and protection were met with quibbling sophistry and hollow professions, only made to be broken as soon as they had served the temporary purpose of averting immediate punishment; that, in short, he was not dealing with a man who had a mind impressed with those principles of rectitude, or that standard of action called "conscience," which might have guided him to observe common candour and fairness in his dealings.In reply, Mr. Buckingham tacitly admitted that, in forming this judgment of him, Lord Hastings was not far from correct. The old censorship had been bad; the new restrictions were bad; but that the conductors of the press were to be guided by the rules of common honesty, he held to be worse still.

"I must now (he says), I fear, consider your letter of the 17th as establishing a new criterion, in lieu of the former, more safe, because more clearly defined guides for publication." Common honesty and justice, a new and severe criterion for him, though the judge were one of the most pure and magnanimous of men! But, indeed, he might think that the more upright the judge, so much the worse for the transgressor. In conclusion, Mr. Buckingham says:

"If so severe a punishment as banishment and ruin is to be inflicted on a supposed violation of the laws of moral candour and essential justice, of which I know not where to look for any definite standard, I fear that my best determinations will be of no avail."

Lord Hastings might have replied, that all good men look in their own breasts to the standard of honesty, which God has planted there. That it is to this standard, under heaven, all human actions must ultimately be referred, whether it be applied in the form of trial by jury, decision by a single judge, by a bench of justices, by a Governor, or by a Council: therefore no Government has yet enacted laws to define or determine what honesty and truth are, because they are supposed to be known to all; and the man who has them not implanted in his mind by nature, is unfit to live in human society. Pontius Pilate, indeed, once asked, "what is truth?" The divine founder of Christianity made no reply. When it was now asked, in the same sneering manner, "what are the rules of honesty and justice?" the good and virtuous Lord Hastings felt that it would be unworthy of him to reply. Consequently the following note was addressed to Mr. Buckingham:

"Sir: I am directed by his Excellency the most noble the Governor General in Council, to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 27th ultimo, and to inform you, that the letter in question has produced no change in the sentiments and resolutions of Government, already communicated to you on the 17th ultimo."

4thly. Attacks on Lord Hastings' Administration. -- The following extracts, of another letter from the Government, and Mr. Buckingham's reply to it, are an apt illustration of his confessed unacquaintance with the rules of "moral candour and essential justice:"

To Mr. J. S. Buckingham, Editor of the Calcutta Journal.

Sir: The attention of the Governor General in Council has been called to a discussion in the Calcutta Journal of the 31st ultimo, respecting the power of Government to forbid the further continuance within the British territories in India, of any European not being a covenanted servant of the Honourable Company.

With a suppression of facts, most mischievous, as tending to betray others into penal error, you have put out of view the circumstance that the residence alluded to, if it be without a license, is criminal by the law of England; while, if the residence be sanctioned by license, it is upon the special recorded condition, not simply of obedience to what the local Government may see cause to enjoin, but to the holding a conduct which that Government shall deem to merit its countenance and protection; a breach of which condition forfeits the indulgence, and renders it liable to extinction.

This provision, which the legislature of your country has thought proper to enact (53 Geo. IIII. cap. 155, sect. 36), you have daringly endeavoured to discredit and nullify, by asserting that 'transmission for offences through the press is a power wholly unknown to the law;' that 'no regulation exists in the statute book for restraining the press in India;' and that 'the more the monstrous doctrine of transmission is examined, the more it must excite the abhorrence of all just minds.'

No comment is requisite on the gross disingenuousness of describing as a tyrannous authority that power, the legality and justice of which you had acknowledged by your voluntary acceptance of a leave, granted on terms involving your express recognition to that effect. Neither is it necessary to particularize the many minor indecencies in the paper observed upon, since you have brought the matter to one decisive point.

Whether the act of the British Legislature, or the opinion of an individual shall be predominant, is now at issue. It is thence imperative on the duty of the local Government to put the subject at rest. The long-tried forbearance of the Governor General will fully prove the extreme reluctance with which he adopts a measure of harshness; and even now, his Excellency in Council is pleased to give you the advantage of one more warning. You are now finally apprized, if you shall again venture to impeach the validity of the statute quoted, and the legitimacy of the power vested by it in the chief authority here, or shall treat with disregard any official injunction, past or future, from Government, whether communicated in terms of command, or in the gentler language of intimation, your license will be immediately cancelled, and you will be ordered to depart forthwith from India."

In replying to the above, Mr. Buckingham gave the following piece of an argument between him and a cotemporary journal:

"With the most wilful blindness to all that had been passing for the last four years in India, the editor of John Bull opened his dissertation with the following singular confession: 'In the first place, then, we must begin by acknowledging candidly, that till Thursday last, when the matter was announced in the Calcutta Journal, we had not the most remote idea that a free press was established in India;' and then goes on to insinuate that the professions of the Governor General were of no value whatever, and that that freedom of the press for which he had so justly received the thanks and admiration of his countrymen from all quarters of India, not only did not exist now, but never had, and never was intended to have, any force or meaning whatever.

On the following day (August 27), I noticed these ungenerous, and, as they appeared to me, unwarranted assertions of my opponent, by saying that I believed the wish of the Governor General was in unison with his professions, that the press should be held amenable to the courts of law for its offences (that being the process observed by his Lordship in the majority of the cases in which he had thought proper to interfere, and in the most recent instances also); and that if this were the case, the press must be considered free; for all that was ever meant by me in using that term, was, free from any other restraint or control than that imposed by a court of law and a jury."

Here Mr. Buckingham alleges, that by all that had occurred during the last three years, Lord Hastings must be held to have declared that the press was to be free from any restraint but "a court of law and a jury;" and that if his lordship did not mean this, it is insinuated that he was an arrant hypocrite and a deceiver. What is the fact? That the whole of Lord Hastings' declarations, even in the reply to the Madras address itself, were the very reverse of what Mr. Buckingham here pretends. They were that the liberty of the press was to be narrowed by "special and urgent cause assigned," and to be restrained, therefore, both by the laws of England, and by the further limitations specified in Lord Hastings' regulation, enacted expressly for the Indian press.

But the most singular thing is, that a little afterwards, in the very same letter, Mr. Buckingham asserts that the laws of England imposed no legal restraint on the Indian press. His words are:

"I beg distinctly to state, that so far from having suppressed the fact of its being unlawful for Englishmen to reside in India without license, I have admitted and reiterated that fact times beyond number, always making it the ground of my argument for saying that the fear of having this license withdrawn, and being therefore sent to England as a person unauthorized to remain in India, is the most powerful as well as the only legal restraint even now exercised over the Indian press."

What an admirable and consistent advocate of free discussion, to discover and point out to the Government, that the exercise of the power of "summary transportation without trial" was "their only legal mode of regulating the press!" Then the recourse which had been had "in the most recent instances" (as he had a little before stated), to a court of law, must have been highly illegal and improper! In the next paragraph he goes on to say:

"Neither on the statute book of England nor the statute book of India, by which I mean the printed and public regulations of the Government, issued and passed in the usual form, am I aware of any law for restraining the Indian press."

Here then, in the same letter, were three propositions maintained:--

1st. That the press was free from any other restraint than that imposed by a court of law and a jury.

2dly. That the legal, and the ONLY legal restraint existing, was that of summary transportation without trial.

3dly. That there was no law, either in England or in India, for restraining the press there, which was consequently more free than the English press itself.

These three were brought forward to prove the truth of a fourth proposition, namely, his former assertion which had been condemned by the Government, viz.

4thly. That transmission (to England) for offences through the press, was a power wholly unknown to the law.

The man who could assert in the same letter these different and diametrically opposite propositions, might well think it a grievous hardship to be tried by the rules of "moral candour and essential justice," and say, he knew not where to look for any definite standard of them!

It would be useless to pursue further such a maze of endless contradictions. It is enough to state that Mr. Buckingham continued to follow the same course, and employed the whole energies of the press, invigorated as it had become by the degree of liberty conferred upon it by Lord Hastings, to cast a shade on the character and closing administration of this nobleman: its generous, and now almost only protector, to whose magnanimity and indulgence Mr. Buckingham himself owed his good fortune and even existence in Bengal; but for which he must have been expelled (as he had before been from Bombay), and thrown upon the world again, a needy adventurer, to live by his wits or the precarious bounty of his friends.It is now clear enough that

Mr. Buckingham was secretly of this same opinion, and felt conscious that as soon as Lord Hastings, now the object of his revilings, left the country, all hopes of farther protection or impunity were at an end. This event was to take place in the beginning of the year 1823, and in the latter part of 1822 Mr. Buckingham prepared for the coming storm. He resorted to the following notable plan of selling out the property he had in his Journal.

He proposed to convert the concern into a sort of joint-stock company, by selling it in shares of 1,000 rupees (or about £100) each. As an inducement to purchase these shares, he informed the public, that the concern was worth four lacs of rupees (or about £40,000 sterling); that this amount was made up one-half of copyright, one-fourth of property on the spot, and the remaining fourth of property, types, presses, &c. ordered from Mr. Richardson, (28, Cornhill,) his agent in England."These [says the prospectus, from which I quote the words] will all leave England before the end of this year (1822), and some portions are now on their way out; all of which being to be paid before, out of my funds, by a credit on Fletcher, Alexander, and Co.* [Then of Devonshire Square, now of King's Arms Yard, Coleman Street.] to cover insurance and every risk, must be added to the dead stock of the concern, which will make its whole value amount to 2,00,000 rupees, as the security on which the shares taken are to be held."

On this security, to which he bound himself by legal contract, he sold by his own account 100 shares, obtaining for the same gross sum of 1,00,000 rupees or nearly £10,000 sterling. Now, though the purchasers might have formed a rough estimate of the value of property on the spot, or the copyright of a paper, provided the accounts were fairly stated, it is evident they could form no judgment of the value of goods stated to be on the way from England. These they must have taken on the confidence that the individual who said he had commissioned and sent funds to pay for them was acting with good faith; and that if he sold property which had no existence, in order to put the price thereof into his pocket, he would come within the provisions of the useful statute enacted against the obtaining of money on false pretences.

Though it may be anticipating, it is proper to state here, in connection with this project, that the agent referred to in England has since stated that he did not send goods to any thing near the amount specified, or even so much as a fifth part of the sum, at the period to which this contract applies. And there is no evidence yet produced of the funds having been remitted to obtain them. It is no marvel, therefore, if in India no proofs appeared of their ever having arrived; and the whole materials of the concern were soon after sold by public auction (the ordinary mode of disposing of property in Bengal, and adopted in this case, therefore, by Mr. Buckingham's agents as the most advantageous), for less than two thousand pounds, a tenth part of the amount contracted for as "the security on which the share taken were to be held!" The reader may form his own judgment as to the causes of this most extraordinary discrepancy.The real value of the copyright of the Journal, allowing it to be worth six months' produce of the gross receipts, or two years of the net profit, would have been about £8,000; but this is a very high calculation, considering that it was a Journal of such ephemeral standing, and liable to be suppressed daily by the arbitrary banishment of its conductors. Adding to this the above sum of £2,000 for actual tangible property, we have a total value of £10,000, just equal to the sum Mr. Buckingham had raised by the sale of shares.

The condition on which these shares were held made them a kind of mortgage over the concern; as the holder of each became entitled to a daily paper of sixteen quarto pages free of charge (except postage), costing sixteen rupees per mensem, and amounting in all, for 100 shares, to Sa. Rs. 19,200 per annum, or nearly £2.000 sterling yearly. Besides this, as the whole concern was conceived to be divided into 400 shares, each of which was to be entitled to a corresponding proportion of the profits, the 100 shares sold would absorb one-fourth of the whole net receipts or profits. Supposing these to be, as Mr. Buckingham has so often since asserted, £8,000 per annum, the fourth of this added to the above £2,000 would render the annual charge upon the concern £4,000. But his own printed estimate of the actual receipts and disbursements for the last six months of 1822, which he published at that time in Bengal, made the net profit to be no more than 25 per cent on the receipts, or about £4,500 in all. The same estimate represented the shareholders as drawing an interest of 308 rupees per annum on each share, which for 100 shares is equal to 30,800, or in round numbers about £3,000 yearly.

Such was the weighty consideration which Mr. Buckingham had bound himself, "his heirs, executors, and administrators," to make good for seven years, to the purchasers of shares (or mortgagees, as they may well be called). He had also bound himself to give his own personal services for three years; and not voluntarily to leave the country under a penalty of 50,000 rupees. He had further contracted to export to the concern property to the amount of 100,000 rupees as above shewn. Now he knew that if the government could only be provoked to remove him from the country he would, in the first place, be relieved of the above 50,000 rupees penalty. 2dly, He would be removed from the severe exposures of his character to which he was now subjected, on account of his previous conduct in Egypt and Syria.

3dly, He would be out of hearing of any clamours that might be raised about the fulfilment of his contract, as to the promised exportation of the property to the value of £10,000. Lastly, if others in his absence should by possibility succeed in carrying on such a concern, with a burden upon it of above £3,000 per annum, the labour, and anxiety, and waste of health, would fall upon them. If they failed, or sunk under it, and the concern with them, then he would get rid of all his remaining obligations, and have his £10,000 snug in his pocket! Under these circumstances, the following is the contumelious stile in which he wrote of the venerable Marquis of Hastings, at first his patron, and to the last, notwithstanding so many years of misrepresentation, contumacy, and insolence, his magnanimous protector against the numerous and powerful enemies his controversies, turbulence, and slanders, had raised against him. He tauntingly told his Lordship, now on the eve of his departure, and adopting the figure of speech which he thought would be most galling to an aged military chief:--"The banners by which the free press of India was first protected, have been since unhappily abandoned, deserted, fallen, and IGNOMINIOUSLY furled, by the very hands that were the first to unfold and wave them in pride and exultation over our heads."

This self-confuted invective was directed against a Governor-General of India in the plenitude of his power. With one word he might have banished his defamer to the ends of the earth, -- from Bengal to the shores of Europe; knowing that every member of his government would have applauded the deed. But he neither punished, nor expressed the resentment. Yet persons were found so unjust and ungrateful, as to employ that freedom which the Marquis of Hastings had bestowed on the Indian press, to accuse him of basely deserting his principles, and covering himself with ignominy! That very press, whose tongue he had unshackled, employed its liberty to load him with insult; and the very man whom his protection had saved from beggary and ruin, and fostered into consequence, employs it to tarnish his name, and, if possible, dim the lustre of that well-earned fame, which had been consecrated, and rendered venerable, by the accumulated honours of nearly half a century.

Lord Hastings soon after took his departure for Europe. And when the influence of his benignant character ceased to shine upon India, the liberty of the press which he had established, and all the hopes of improvement associated with it, soon sunk with him into the darkest night. This will be more fully illustrated in the following chapter.