by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/20/21

-- Chapter V. The Three Bureaus of Information, Excerpt from "Influential Centres of Disaffection": Indian Students in Edwardian London and the Empire that Shaped Them, by William H. Cowell

-- William Lee-Warner, by Wikipedia

-- James Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, by Wikipedia

-- Theodore Morison, by Wikipedia

-- National Indian Association, by Wikipedia

-- Royal India Society [India Society] [Royal India and Pakistan Society] [Royal India, Pakistan and Ceylon Society], by Wikipedia

-- Northbrook Society [Northbrook Indian Society] [Northbrook Club] [Northbrook Indian Club], by The Open University: Making Britain

-- Thomas Baring, 1st Earl of Northbrook, by Wikipedia

-- Thomas Walker Arnold, by Wikipedia

-- Indian Political Intelligence Office, by Wikipedia

-- John Wallinger, by Wikipedia

-- Mansfield Smith-Cumming, by Wikipedia

-- Shivaji [Chhatrapati Shivaji], by Wikipedia

-- All-India Muslim League, by Wikipedia

-- Ain-i-Akbari, by Wikipedia

The Scientific Society of Aligarh was a literary society founded by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan at Aligarh. The main objectives of the society was to translate Western works on arts and science into vernacular languages and promote western education among the masses.

History

On January 9, 1864 Sir Syed formed a translation society called Scientific Society at Ghazipur with the goal of translating scientific books of English and other European languages into Urdu and Hindi.[2] The first meeting was held in January 1864 under the presidentship of Mr. A. B. Spate, the then Collector of Ghazipur.[3] This society was moved in April 1864 to Aligarh and henceforth also known as the Scientific Society of Aligarh.[4] The society sought to promote liberal, modern education and Western scientific knowledge in the Muslim community in India. The society was modelled after the Royal Society and the Royal Asiatic Society. Sir Syed assembled Muslim scholars from different parts of the country and the society held annual conferences, disbursed funds for educational causes and regularly published a journal on scientific subjects in English and Urdu.[5]

Many of the essays he wrote during this time were on topics like the solar system, plant and animal life, human evolution, etc. In many ways, Sir Syed tried to bridge the gap between religion and science.

Members

Jai Kishan Das, close Hindu associate of Sir Syed served as its secretary from 1867 till 1874.[6][7][8] He was also nominated as Co-President of The Society for life.[9] Other active members of the society included Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk, Nawab Abdul Latif, Zakaullah Dehlvi, Nazir Ahmad Dehlvi, and Kunwar Luft Ali Khan of Chhattari.[1] The society also appointed two translators: Babu Ganga Prasad was an English translator and Moulvi Faiyazul Hasan was the vernacular translator.[10]

Institute

The Aligarh Scientific Society had a library and a reading room of its own. The books were mainly donated to the Society by different Indian as well as foreign gentlemen.

Sir Syed himself donated a large number of books to the library. The Society subscribed to forty-four journals and magazines in 1866. Of those, 18 were in English and rest in Urdu, Persian, Arabic and Sanskrit. It exchanged its publication with similar societies like the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge founded by Pandit Harsokh Rai at Lahore and the Mohammedan Literary Society founded by Nawab Abdul Latif at Calcutta. It also exchanged its journal with the publications of the Bengal Asiatic Society, Calcutta.[11]

Publications

Aligarh Institute Gazette was the journal of the society.[12]It was the first bilingual journal of India.[13]

References

1. Azmi, Arshad Ali (1969). "The Aligarh Scientific Society 1864-1867". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 31: 414–420. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44138412.

2. "Scientific Society | Aligarh Movement". aligarhmovement.com. Retrieved 2020-12-25.

3. Kidwai, Shafey (2020-12-03). Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: Reason, Religion and Nation. Taylor & Francis. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-000-29773-7.

4. "Scientific Society | Aligarh Movement". aligarhmovement.com. Retrieved 2020-12-25.

5. Singh, M. K. (2009). Encyclopaedia of Indian War of Independence, 1857-1947: Muslims and other freedom fighters : C. Rajgopalachari, M.M. Malviya, Dr. Zakir Hussain, Abdul Gaffar Khan, Syed Ahmed Khan, R.K. Kidwai and M.A. Ansari. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-261-3745-9.

6. "Remembering Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, the great educationist and secular nationalist". India TV News. 2015-10-17. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

7. Dildār ʻAlī Farmān Fatiḥpūrī; Dild−ar ʻAl−i Farm−an Fatiḥp−ur−i (1987). Pakistan movement and Hindi-Urdu conflict. Sang-e-Meel Publications.

8. Muhammad Moj (1 March 2015). The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and Tendencies. Anthem Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-1-78308-388-6.

9. Fatiḥpūrī, Dildār ʻAlī Farmān; Fatiḥp−ur−i, Dild-ar ʻAl−i Farm−an (1987-01-01). Pakistan movement and Hindi-Urdu conflict. Sang-e-Meel Publications.

10. Kidwai, Shafey (2020-12-03). Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: Reason, Religion and Nation. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-000-29773-7.

11. "NPTEL :: Humanities and Social Sciences - Science, Technology and Society" (PDF).

12. Moj, Muhammad (2015-03-01). The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and Tendencies. Anthem Press. ISBN 9781783083886.

13. "Scientific Society | Aligarh Movement". aligarhmovement.com. Retrieved 2020-12-25.

External links

• [1]

*********************************

Aligarh Muslim University

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/20/21

Aligarh Muslim University

Other name: AMU

Former names: Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College (1875–1919)

Motto: ʻallam al-insān-a mā lam yaʻlam (Taught man what he knew not (Qur'an 96:5))

Type: Public

Established: 1875; 146 years ago

Founders: Sir Syed Ahmed Khan

Academic affiliations: UGC, NAAC, AIU

Budget: ₹1,036 crore (US$140 million) (2019–20)[1]

Chancellor: Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin

Vice-Chancellor: Tariq Mansoor

Rector: Governor of Uttar Pradesh

Students: 18,618[2]

Undergraduates: 12,610[2]

Postgraduates: 5,756[2]

Doctoral students: 252[2]

Location: Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

27.9150°N 78.0788°ECoordinates: 27.9150°N 78.0788°E

Campus: Urban, 1,155 acres (467 ha)

Website: http://www.amu.ac.in

Aligarh Muslim University (abbreviated as AMU) is a public central university in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, which was originally established by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875. Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College became Aligarh Muslim University in 1920, following the Aligarh Muslim University Act. It has three off-campus centres in AMU Malappuram Campus (Kerala), AMU Murshidabad centre (West Bengal), and Kishanganj Centre (Bihar). The university offers more than 300 courses in traditional and modern branches of education, and is an institute of national importance as declared under seventh schedule of the Constitution of India at its commencement.

The university has been ranked 801–1000 in the QS World University Rankings of 2021,[3] and 10 in India by the National Institutional Ranking Framework in 2021.[4] Various clubs and societies function under the aegis of the university and it has various notable academicians, literary figures, politicians, jurists, lawyers, and sportspeople, among others as its alumni.

History

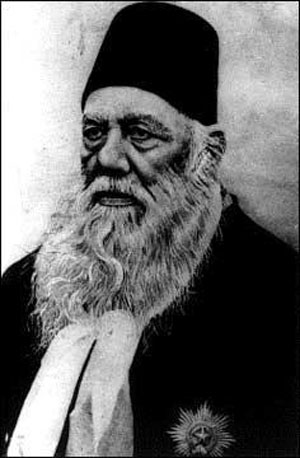

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, the founder of Aligarh Muslim University

Bab-e-Syed, entrance to the university

Funding

The university was established as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875 by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan,[5][6] starting functioning on 24 May 1875.[7] The movement associated with Syed Ahmad Khan and the college came to be known as the Aligarh Movement, which pushed to realise the need for establishing a modern education system for the Indian Muslim populace.[8] He considered competence in English and Western sciences necessary skills for maintaining Muslims' political influence.[citation needed] Khan's vision for the college was based on his visit to Oxford University and Cambridge University, and he wanted to establish an education system similar to the British model.[9]

A committee was formed by the name of foundation of Muslim College and asked people to fund generously. Then Viceroy and Governor General of India, Thomas Baring gave a donation of ₹10,000 while the Lt. Governor of the North Western Provinces contributed ₹1,000, and by March 1874 funds for the college stood at ₹1,53,920 and 8 annas.[7] Maharao Raja Mahamdar Singh Mahamder Bahadur of Patiala contributed ₹58,000 while Raja Shambhu Narayan of Benaras donated ₹60,000.[10] Donations also came in from the Maharaja of Vizianagaram as well.[11] The college was initially affiliated to the University of Calcutta for the matriculate examination but became an affiliate of Allahabad University in 1885. [7] The seventh Nizam of Hyderabad, HEH Mir Osman Ali Khan made a remarkable donation of Rupees 5 Lakh to this institution in the year 1918. [12][13][14]

Establishment as university

Masjid at the Aligarh Muslim University

Circa 1900, Muslim University Association was formed to spearhead efforts to transform the college into a university. The Government of India informed the association that a sum of rupees thirty lakhs should be collected to establish the university. Therefore, a Muslim University Foundation Committee was started and it collected the necessary funds. The contributions were made by Muslims as well as non-Muslims.[15] Mohammad Ali Mohammad Khan and Aga Khan III had helped in realising the idea by collecting funds for building the Aligarh Muslim University.[16] With the MAO College as a nucleus, the Aligarh Muslim University was then established by the Aligarh Muslim University Act, 1920.[9][17] In 1927, the Ahmadi School for the Visually Challenged, Aligarh Muslim University was established and in the following year, a medical school was attached to the university. The college of unani medicine, Ajmal Khan Tibbya College was established in 1927 with the Ajmal Khan Tibbiya College Hospital being established later in 1932.[18] The Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College And Hospital was established later in 1962 as a part of the university.[19] In 1935, the Zakir Husain College of Engineering and Technology was also established as a constituent of the university.[20]

Before 1939, faculty members and students supported an all-India nationalist movement but after 1939, political sentiment shifted towards support for a Muslim separatist movement. Students and faculty members supported Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the university came to be a center of the Pakistan Movement.[21][22]

Women's education

Dr. Sheikh Abdullah ("Papa Mian") is the founder of the women's college of Aligarh Muslim University and had pressed for women's education, writing articles while also publishing a monthly women's magazine, Khatoon. To start the college for women, he had led a delegation to the Lt. Governor of the United Provinces while also writing a proposal to Sultan Jahan, Begum of Bhopal. Begum Jahan had allocated a grant of ₹ 100 per month for the education of women. On 19 October 1906, he successfully started a school for girls with five students and one teacher at a rented property in Aligarh.[23] The foundation stone for the girls' hostel was laid by him and his wife, Waheed Jahan Begum ("Ala Bi") after struggles on 7 November 1911.[23] Later, a high school was established in 1921, gaining the status of an intermediate college in 1922, finally becoming a constituent of the Aligarh Muslim University as an undergraduate college in 1937.[24] Later, Dr. Abdullah's daughters also served as principals of the women's college.[23] One of his daughters was Mumtaz Jahan Haider, during whose tenure as principal, Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad had visited the university and offered a grant of ₹9,00,000. She was involved in the establishment of the Women's College, organised various extracurricular events, and reasserted the importance of education for Muslim women.[25]

In 2014, then vice-chancellor Zameer Uddin Shah turned down a demand by female students to be allowed to use the Maulana Azad Library, which was males-only. Shah stated that the issue was not one of discipline, but of space as if girls were allowed in the library there would be "four times more boys", putting a strain on the library's capacity. [26][27][28] Although there was a separate library for the university's Women's College, it was not as well-stocked as the Maulana Azad Library[26] Union Minister of Human Resource Development, Smriti Irani decried Shah's defence as "an insult to daughters".[27] Responding to a petition filed by Human Rights Law Network, the Allahabad High Court ruled in November 2014 that the university's ban on female students from using the library was unconstitutional, and that accommodations must be made to facilitate student's use regardless of gender.[28][29] The Court gave the university time until 24 November 2014 to comply.[29]

Minority institution status

Aligarh Muslim University is considered to be institution of national importance, under the seventh schedule of the Constitution of India.[30][31] In 1967, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court had held that the university is not a minority educational institution protected under the Indian constitution; the verdict had been given in case to which the university was not a party.[32] In 1981, an amendment was made to the Aligarh Muslim University Act, following which in 2006 the Allahabad High Court struck down the provision of the act which accorded the university minority educational institution status.[33] In April 2016, the Indian government stated that it would not appeal against the decision.[34][35] In February 2019, the issue was referred by the Supreme Court of India to a constitution bench of seven judges.[33][32]

Campus

The Syedna Taher Saifuddin School.

Victoria Gate.

Sir Syed House.

The campus of Aligarh Muslim University is spread over 467.6 hectares in the city of Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh. The nearest railways station is the Aligarh Junction. It is a residential university with most of the staff and students residing on the campus. There are 19 halls of residence for students (13 for boys and 6 for girls) with 80 hostels.[36] The Halls are administered by a Provost and a number of teacher wardens who look after different hostels. Each Hall maintains a Dining Hall, a Common Room with facilities for indoor games, a Reading Room, Library, Sports Clubs and a Literary.[37] The Halls are named after people associated with the Aligarh Movement and the university.

Sir Syed Hall is the oldest Hall of the university. It houses many heritage buildings such as Strachey Hall, Mushtaq Manzil, Asman Manzil, Nizam Museum and Lytton Library, Victoria Gate, and Jama Masjid.[38]

The campus also maintains a cricket ground, Willingdon Pavilion, a synthetic hockey ground and a park, Gulastan-e-Syed.[39]

Other notable buildings in the campus includes the Maulana Azad Library, Moinuddin Ahmad Art Gallery, Kennedy Auditorium, Musa Dakri Museum, the Cultural Education Centre, Siddons Debating Union Hall and Sir Syed House.[40][41][42]

The main university gate is called Bab-e-Syed. In 2020 a new gate called Centenary Gate was built to celebrate the centenary year of the university.[43]

Organisation and administration

Governance

The university's formal head is the chancellor, though this is a titular figure, and is not involved with the day-to-day running of the university. The chancellor is elected by the members of the University Court. The university's chief executive is the vice-chancellor, appointed by the President of India on the recommendation of the court. The court is the supreme governing body of the university and exercises all the powers of the university, not otherwise provided for by the Aligarh Muslim University Act, and the statutes, ordinances and regulations of the university.[44]

In 2018, Mufaddal Saifuddin was elected chancellor and Ibne Saeed Khan, the former Nawab of Chhatari was elected the pro-Chancellor. Syed Zillur Rahman was elected honorary treasurer.[45] On 17 May 2017, Tariq Mansoor assumed office as the 39th vice-chancellor of the university.[46]

Faculties

Aligarh Muslim University's academic departments are divided into 13 faculties.[47]

• Faculty of Agricultural Sciences

• Faculty of Arts

• Faculty of Commerce

• Faculty of Engineering & Technology

• Faculty of Law

• Faculty of Life Sciences

• Faculty of Medicine

• Faculty of Management Studies & Research

• Faculty of Science

• Faculty of Social Sciences

• Faculty of Theology

• Faculty of International Studies

• Faculty of Unani Medicine

Colleges

Aligarh Muslim University maintains 7 colleges.[48]

• Women's College

• Zakir Hussain College of Engineering & Technology

• Ajmal Khan Tibbiya College

• Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College

• Dr. Ziauddin Ahmad Dental College

• Community College

• Academic Staff College

In addition the university also maintains 15 Centres, 3 Institutes, 10 schools including Minto Circle and the Ahmadi School for the Visually Challenged[49] The university's Faculty of Theology has two departments, one for the Shi'a school of thought and another for the Sunni school of thought.[50]

Aligarh Muslim University has established three centres at Malappuram (Kerala; the AMU Malappuram Campus), Murshidabad (West Bengal) and Kishanganj (Bihar), while a site has been identified for Aurangabad, (Maharashtra) centre.[51][52]

Academics

Courses

Aligarh Musilim University offers over 300 degrees and is organised around 12 faculties offering courses in a range of technical and vocational subjects, as well as interdisciplinary subjects. In 2011, it opened two new centres in West Bengal and Kerala for the study of MBAs and Integrated Law. The university has around 28,000 students and a faculty of almost 1,500 teaching staff. Students are drawn from all states in India and several different countries, with most of its international students coming from Africa, West Asia and Southeast Asia. Admission into the university is entrance based.[53]

Rankings

Internationally, AMU was ranked 801–1000 in the QS World University Rankings of 2021.[3] The same rankings ranked it 251–260 in Asia in 2020[55] and 138 among BRICS nations in 2019.[56] It was ranked 801–1000 in the world by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings of 2021,[57] 201–250 in Asia[58] and 201–250 among Emerging Economies in 2020.[59] It was ranked 18 in India overall by the National Institutional Ranking Framework in 2020[60] and tenth among universities.[4]

Among government engineering colleges, the Zakir Hussain College of Engineering and Technology, the engineering college of the university, was ranked 32 by India Today in 2020[72] and 35 by the National Institutional Ranking Framework among engineering colleges in 2020.[63]

The Faculty of Law has ranked 11th in India by India Today in 2020.[73] The Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, the medical school of the university, has been ranked 19th by India Today in 2020.[66]

Libraries

Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University

Main article: Maulana Azad Library

The Maulana Azad Library is the primary library of the university, consisting of a central library and over 100 departmental and college libraries. It houses royal decrees of Mughal emperors such as Babur, Akbar and Shah Jahan.[74] The foundation of the library was laid in 1877 at the time of establishment of the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College by Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, then viceroy of India and it was named after him as Lytton Library. The present seven-storied building was inaugurated by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime Minister of independent India, in 1960 and the library was named after Abul Kalam Azad, popularly known as Maulana Azad, the first education minister of the independent India.[74][75]

The social science cyber library was inaugurated by Pranab Mukherjee, then President of India, on 27 December 2013.[76] In 2015, it was accredited with the International Organization for Standardization certification.[77]

AMU Journal

Logo of AMU Journal

AMU Journal is an independent student and alumni-run educational community and media organization,[78][79] it was started in the year 2016 by a group of AMU Students to raise campus issues and to provide News and information about Happening Events inside the university but later it became an educational community. On 17 October 2021 AMU Journal website was re-launched by Public relations officer, Proctor and Deputy Proctor, Aligarh Muslim University in Collaboration with Traning and Placement Office, AMU.[80] AMU Journal has over 200k user online including website and social Media, it has 100k monthly Viewers, 2900 subscribers on YouTube channel, 64k followers on Facebook, and 15k followers on Twitter.

Student life

Traditions

Sherwani is worn by male students of the university and is a traditional attire of the university. It is required to be worn during official programs[81] The university provides sherwanis at a subsidized price.[82] In early 2013, Zameer Uddin Shah, the then Vice Chancellor of the university, insisted that male students have to wear sherwani if they wanted to meet him.[83]

The AMU Tarana or anthem was composed by poet and university student Majaz.[84] It is an abridged version of Majaz's 1933 poem "Narz-e-Aligarh".[85] In 1955, Khan Ishtiaq Mohammad, a university student, composed the song and it was adopted as the official anthem of the university. The song is played during every function at the university along with the National Anthem.[86]

Students' Union

Main article: Aligarh Muslim University Students' Union

Aligarh Muslim University Students' Union (AMUSU) is the university-wide representative body for students at the university. It is an elected body.

Clubs and societies

The university has sports and cultural clubs functioning under its aegis. The Siddons Union Club is the debating club of the university.[87] It was established in the year 1884 and was named after Henry George Impey Siddons, the first principal of the MAO college.[88] It has hosted a politicians, writers, Nobel laureates, players, and journalists, including the Dalai Lama, Mahatma Gandhi, Abul Kalam Azad, Jawahar Lal Nehru.[89] Sporting clubs include the Cricket Club, Aligarh Muslim University[90] and the Muslim University Riding Club.[91]

The Raleigh Literary Society of the university hosts competitive events, plays, and performances,[92][93] including performances of Shakespeare's plays.[94] The society is named after Shakespeare critic, Sir Walter Raleigh who had served as the English professor at the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College from 1885 to 1887.[94]

The Law Society of the university was founded in 1894 as a non-profit student organization. The society publishes law reviews and organizes events, both academic and social, from annual fest to freshers social and farewell party for final year students.[95][96]

Cultural festivals

Every year the various clubs of the university organize their own cultural festivals. Two notable fests are the University Film Club's Filmsaaz and the Literary Club's AMU Literary Festival.

Old Boys' Association

Old Boys' Association is the alumni network of the university. It was established in the year 1898 and has been statutory recognition under AMU, Act 1920.[97]

Notable alumni and faculties

Main pages: List of Aligarh Muslim University alumni, Category:Aligarh Muslim University faculty, and List of Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of Aligarh Muslim University

Following is a list of alumni from the university.[98]

• Alumni from the field of literature and cinema include – Hakim Ahmad Shuja, Saadat Hasan Manto, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Syed Mujtaba Ali,[99][100] Anubhav Sinha, NaseerUddin Shah, Hasrat Mohani and Ahmed Ali.

• Alumni from the field of politics include – Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan KBE, first Muslim Premier of the Punjab; Maulvi Syed Tufail Ahmad Manglori, Indian independence activist and historian;[101] Khwaja Nazimuddin, second governor-general and second prime minister of Pakistan; Ayub Khan, second president of Pakistan; Mohamed Amin Didi, first president of Maldives; Muhammad Ataul Goni Osmani, Commander-in-chief of Bangladesh Forces during the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence; Muhammad Mansur Ali, third prime minister of Bangladesh; Zakir Husain, third president of India;[102] Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, an Indian independence activist; Mohammad Hamid Ansari, twelfth vice-president of India;[103] Arif Mohammad Khan, twenty-second governor of Kerala;[104] Anwara Taimur the first and yet only female chief minister of the Indian state of Assam;[105] Sheikh Abdullah and Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, respectively third and sixth chief minister of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir;[106][107] and Sahib Singh Verma, fourth chief minister of the Indian union territory of Delhi.

• Alumni from the field of law include – Justice Baharul Islam, Justice Ram Prakash Sethi, Justice Saiyed Saghir Ahmad, Justice Syed Murtaza Fazl Ali (all judges of Supreme Court of India), Haji Farah Omar, N. R. Madhava Menon & Faizan Mustafa.

• Alumni from the field of sports include – Dhyan Chand, Lala Amarnath and Zafar Iqbal[108] and Iranian footballer Majid Bishkar

• Other notable alumni include – Indian historian Mohammad Habib,[109] French mathematician André Weil,[110][111] and Malik Ghulam Muhammad, the co-founder of Mahindra & Mahindra.

• Yasin Mazhar Siddiqi Muslim scholar and historian who served as director of the Institute of Islamic Studies

• Bijan Abdolkarimi Iranian philosopher

• Naseem uz Zafar Baquiri Medical Practitioner, Poet

In popular culture

• The 1963 film Mere Mehboob, directed by H. S. Rawail starring Rajendra Kumar, Sadhana, Ashok Kumar was shot on the campus.[112]

• The 1966 film Nai Umar Ki Nai Fasal was also filmed on the campus.[113]

• The 2015 film, Aligarh portrays the struggles faced by Ramchandra Siras, a homosexual professor from the university.[114]

Further reading

• Ahmad, Aijaz (2015). Aligarh Muslim University: An Educational and Political History, 1920–47. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5085-3673-4.

• Graff, Violette (11 August 1990). "Aligarh's Long Quest for 'Minority' Status: AMU (Amendment) Act, 1981". Economic and Political Weekly. 25 (32): 1771–1781. JSTOR 4396615.

• Hasan, Mushirul; Qadri, Mohd. Afzal Husain (1 March 1985). "Nationalist and separatist trends in Aligarh, 1915–47". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 22 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1177/001946468502200101. S2CID 144414983.

• Minault, Gail; Lelyveld, David (1974). "The Campaign for a Muslim University, 1898–1920". Modern Asian Studies. 8 (2): 145–189. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00005448. JSTOR 311636.

• Noorani, A. G. (13 May 2016). "History of Aligarh Muslim University". The Frontline. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

• Ahmed, Fakhar Uddin Ali (2010). Arabic studies in educational institutions of Assam since 1947 (Thesis). India: Gauhati University. pp. 208–211.

References

1. https://api.amu.ac.in/storage//file/101 ... 550072.pdf

2. "NIRF India – Aligarh Muslim University" (PDF). 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

3. "QS World University Rankings 2021". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

4. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Universities)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2021.

5. "Aligarh" in Chambers's Encyclopædia. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 267.

6. Muhammad Moj (2015). The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and Tendencies. Anthem Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-1-78308-388-6. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

7. Cementing Ethics with Modernism: An Appraisal of Sir Sayyed Ahmed Khan's Writings. Gyan Publishing House. 2010. ISBN 9788121210478. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

8. "Syed Ahmad Khan and Aligarh Movement". Jagranjosh.com. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

9. "AMU History". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

10. "AMU Celebrates Its Links With BHU on Sir Syed's Bi-centenary". http://www.news18.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

11. "History of Aligarh Muslim University". Frontline. 27 April 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

12. "Nizam gave funding for temples, and Hindu educational institutions". missiontelangana. 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

13. "Nizam gave funding for temples, Hindu educational institutions". siasat. 10 September 2010.

14. "Nothing is more disgraceful for a nation than to throw into the oblivion its historical heritage and the works of its ancestors". 12 April 2016.

15. Express Tribune. "S. Azeez Basha And Anr vs Union Of India on 20 October, 1967". Retrieved 1 January 2020.

16. Express Tribune (2 November 2013). "To sir with love: Aga Khan III – a tireless advocate for female education". Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

17. "Aligarh Muslim University". Amu.ac.in. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

18. "History of Ajmal Khan Tibbiya College, Faculty of Unani Medicine, AMU". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

19. "Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

20. "Zakir Husain College of Engineering and Technology". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

21. Mushirul Hasan, "Nationalist and Separatist Trends in Aligarh, 1915–47," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (January 1985) 22#1 pp. 1–33

22. "Flashback: Aligarh University – a glorius legacy". Dawn. 6 August 2011.

23. Khan, Showkat Nayeem (22 May 2015). "The Other Sheikh Abdullah". The Greater Kashmir. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

24. "History of Women's College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

25. Alvi, Albeena (13 June 2019). "Mumtaz Jahan Haider: The First Principal Of Women's College Aligarh". Feminism in India. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

26. Eram Agha, Girls in AMU library will ‘attract’ boys: VC Archived 20 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The Times of India, 11 November 2014.

27. Irani slams AMU V-C over women in library remark Archived 20 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Hindustan Times, 11 November 2014.

28. Allow entry of girls inside library: Allahabad High Court to AMU Archived 25 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Deccan Chronicle, 25 November 2014.

29. India court library ban on women 'unconstitutional' Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News Online, 14 November 2014.

30. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

31. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

32. "AMU issue referred to Constitution Bench". The Hindu. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

33. "Minority Status to Aligarh Muslim University to be Decided by Supreme Court's 7-judge Bench". News18. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

34. "AMU row: Centre to withdraw UPAs appeal, push for non-minority status". indiatoday.intoday.in. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

35. Rautray, Samanwaya (4 April 2016). "Modi government seeks more time from SC to file application in Aligarh Muslim University case". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

36. "Aligarh Muslim University :: Home". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

37. "Aligarh Muslim University || Hostel". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

38. "Aligarh Muslim University || Halls". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

39. "North Zone Intervarsity Tournament begins at AMU". India Education Diary. 22 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

40. "Aligarh Muslim University || Sir Syed Academy". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

41. "Aligarh Muslim University || Musa Dakri Museum". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

42. "Aligarh Muslim University time capsule update". http://www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

43. "AMU VC urged to name centenary gate after Sardar Patel or Ambedkar or Ashfaqullah Khan". The Times of India. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

44. "Aligarh Muslim University || Registrar Section". Amu.ac.in. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

45. "AMU court elects Chancellor, Pro Chancellor and Treasurer". The Times of India. 2 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

46. "Aligarh Muslim University || Department Page". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

47. "Aligarh Muslim University - Faculties". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

48. "Aligarh Muslim University - Colleges". http://www.amu.ac.in. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

49. "Aligarh Muslim University – Faculties". Amu.ac.in. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

50. Mustafa, Faizan (23 November 2017). "UGC's audit report on AMU demonstrates its ignorance of law". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

51. Ganapatye, Shruti (3 November 2018). "Aligarh Muslim University renews idea for campus in state". Mumbai Mirror. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

52. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

53. "Aligarh Muslim University". Times Higher Education (THE). 17 September 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

54. "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". Institute of Higher Education, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

55. "QS Asia University Rankings 2020". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020.

56. "QS BRICS University Rankings 2019". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2018.

57. "Top 1000 World University Rankings 2021". Times Higher Education. 2020.

58. "Times Higher Education Asia University Rankings (2020)". Times Higher Education. 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

59. "Times Higher Education Emerging Economies University Rankings (2020)". Times Higher Education. 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

60. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Overall)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2021.

61. "The Week India University Rankings 2019". The Week. 18 May 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

62. "Top 75 Universities In India In 2020". The Outlook. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

63. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Engineering)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2021.

64. "Best ENGINEERING Colleges 2020: List of Top ENGINEERING Colleges 2020 in India". indiatoday.in. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

65. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Medical)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2020.

66. "Best MEDICAL Colleges 2020: List of Top MEDICAL Colleges 2020 in India". http://www.indiatoday.in. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

67. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Law)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2020.

68. "Top 40 Law Colleges". India Today. 27 May 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

69. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Management)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2021.

70. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Architecture)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2021.

71. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2021 (Dental)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 9 September 2021.

72. "Best ENGINEERING Colleges 2020: List of Top ENGINEERING Colleges 2020 in India - Page31". http://www.indiatoday.in. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

73. "Best LAW Colleges 2020: List of Top LAW Colleges 2020 in India - Page10". http://www.indiatoday.in. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

74. "AMU at 5th spot on India Today Universities Rankings 2012". Indiatoday.intoday.in. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

75. "Aligarh Muslim University || M.A. Library". Amu.ac.in. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

76. "President of India inaugurates XXXVII Indian Social Science Congress". Batori.in. batori. 27 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

77. "Aligarh Muslim University 'cyberary' gets ISO certification". Business Standard India. 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

78. "Aligarh Muslim University Student Start Online Portal to Disseminate AMU-Related News". Retrieved 6 November 2021.CNN-News18

79. "oficial AMU Journal website". amujournal.com. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

80. "Aligarh Muslim University launches student run AMU journal's website". Retrieved 19 November 2021.

81. "Is Lt Gen Zameeruddin Shah reviving 'Sherwani Culture' in AMU?". TwoCircles.net. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

82. "For AMU students, wearing sherwani no issue". archive.indianexpress.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

83. Bhalla, Sahil. "This isn't the first time the Aligarh Muslim University VC has said something outrageous". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

84. "AMU Tarana or Anthem" (PDF). Aligarh Muslim University.

85. "Read full nazm by Asrarul Haq Majaz". Rekhta. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

86. Agha, Eram (17 October 2015). "Majaz's Tarana gets a remix". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

87. "The Siddons Union Club". 20 February 2019.

88. Agha, Eram (24 October 2014). "AMU: A students' union with no party allegiance". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

89. "Hall of free speech at centre of portrait row". http://www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

90. Guha, Ramachandra (2014). A Corner of a Foreign Field: The Indian History of a British Sport (New and Updated ed.). Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9789351186939. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

91. "Galloping to glory". The Hindu. 26 February 2011. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

92. Siddiqui, Mohammad Asim (8 December 2016). "Political Adaptations: Raleigh Literary Society's "Waiting for Godot" and "Hayadavana"". The Theatre Times. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

93. "Raleigh Literary Society of AMU organises a series of competitions". Aapka Times. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

94. Siddiqui, Mohammad Asim (22 April 2016). "Aligarh and its Shakespeare wallahs". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

95. "Aligarh Muslim University || Law Society". http://www.amu.ac.in.

96. "Aligarh Muslim University Vice Chancellor releases Law Society Review and Newsletter". 1 November 2019. |first= missing |last= (help)

97. "Official website AMU Old Boys Association | Alumni aligarh Muslim University". amuoldboysassociation.com. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

98. https://www.amu.ac.in/pdf/Alumni.pdf

99. "Syed Mujtaba Ali – the Pioneer of the Language Movement | BeAnInspirer".

100. "Syed Mujtaba Ali as a Rebel". 7 March 2015.

101. "Syed Tufail Ahmad Manglori". The Milli Gazette. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

102. "Encyclopædia Britannica- Biography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

103. "Hamid Ansari: From diplomat to Vice-President". Firstpost. 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

104. "Arif Mohammad Khan a good orator". Hindustan Times. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

105. "Anwara Taimur – The First Lady CM of Assam". sevendiary.com. 21 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

106. "Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah". Britannica. Britannia. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

107. "The life and career of Mufti Mohammad Sayeed". India Today. Jammu. 7 January 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

108. "Some hearts still beat for hockey here". India Today. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

109. "Mohammad Habib Hall". Aligarh Muslim University. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

110. "Borel, Armand" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

111. "Mufti Mohammad Sayeed – A suave politician". The Indian Express. 7 January 2016. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

112. Siddiqui, Mohammad Asim (3 March 2016). "'Aligarh' goes beyond Aligarh". The Hindu. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

113. "Tigmanshu Dhulia to shoot at Aligarh Muslim University?". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. 15 March 2014. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

114. "Aligarh review: Manoj Bajpayee touches your heart, changes perceptions". Hindustan Times. 25 February 2016. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.