by Ludo Rocher

edited by Donald R. Davis, Jr.

foreword by Richard W. Lariviere

February, 2013

Chapter 4: Law Books in an Oral Culture: The Indian Dharmasastras

In 1772 the British authorities in Calcutta decided that, to be fair to the Indians, they should administer to them not British laws, which the Indians did not know and would not understand, but the local Hindu and Muslim laws, which they not only understood but had held in high esteem for centuries.87 [Governor Warren Hastings' Plan for the Administration of Justice included a section to the effect that "[ i]n all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste and other religious usages or institutions, the laws of the Koran with respect to the Mohamedans and those of the Shaster with respect to the Gentoos shall invariably be adhered to." It became law as S. 27 of the Administration of Justice Regulation of 11 April 1780.]

A fair, humane decision it was; a practical, easy decision it was not. The difficulty was not so much with the Muslims: they had the Quran and the Sharia, and many of the Englishmen who were to administer law to them knew Persian, some even Arabic. The problem was with the Hindus. They too, had law books, but these were in Sanskrit, and of that language no Englishman had any notion whatever.

I will pass over the early British solutions to that problem, since they are not relevant to the point I wish to make. I will just note that, after a few years, some courageous Englishmen came to the conclusion that there was only one way to do it right: they had to learn Sanskrit. That and only that would enable them to read the original texts of the Sanskrit law books, without having to depend on intermediaries, pandits, whom they no longer trusted.88 [Pandits were first attached to the Anglo-Indian Courts in 1772; they continued to act as legal counselors until 1864 when their office was abolished. On the distrust of pandits, see, e.g., Derrett 1968: 243.]

The British were told that the laws of the Hindus were contained in books called Dharmasastras, i.e., sastras "text, treatises" on dharma "the aggregate of all the rules which a Hindu is supposed to live by."89 [The term Dharmasastra, in a general sense, is used for both the Dharmasutras, which are in prose, and the Dharma-sastras stricto sensu, which are in verse. The individual Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras are also called smrtis, and the entire corpus of these texts is referred to as part of "the" smrti (literally, "memory"), i.e., a form of revelation inferior only to the higher form of revelation contained in the several Vedic texts (sruti). I must stress that this entire essay deals with this body of texts only, not with the immense commentarial literature on them, which developed at a later time.] The British also learned that the Dharmasastra the Hindus most highly respected was the one attributed to Manu, one of the several ancient sages who are supposed to have composed -- rather, "revealed" -- treatises on dharma.

One of the Englishmen who studied Sanskrit was Sir William Jones, since 1783 a judge in the Supreme Court of Judicature in Calcutta.90 [The fact that Jones' decision to study Sanskrit was linked to his distrust of the Court pandits is highlighted in a letter to Charles Chapman, written from the Bengal town of Krishnagar on 28 September 1785: "I am proceeding slowly, but surely, in this retired place, in the study of Sanscrit; for I can no longer bear to be at the mercy of our pundits, who deal out Hindu law as they please, and make it at reasonable rates when they cannot find it ready-made" (Cannon 1970; 683-684).] In 1794 Jones indeed completed and published, in Calcutta, an English translation of the Dharmasastra attributed to Manu: Institutes of Hindu Law: or, the Ordinances of Menu.

To be sure, Jones' translation, which was "printed by the order of Government," was intended, primarily, to serve the administration of justice. According to Jones, the judge,

it must be remembered, that those laws are actually revered, as the word of the Most High, by nations of great importance to the political and commercial interests of Europe, and particularly by millions of Hindu subjects, whose well directed industry would add largely to the wealth of Britain, and who ask no more in return than protection for their persons and places of abode, justice in their temporal concerns, indulgence to the prejudices of their old religion, and the benefit of those laws, which they have been taught to believe sacred, and which alone they can possibly comprehend. (Jones 1796, rpt. in Haughton 1825: 2.xxi-xxii; see note 92)

Yet, at the same time Jones, the scholar, expressed an opinion that is particularly important in the context of this essay. Jones was convinced that, by translating Manu, he not only had access to the laws to be applied to Hindus in 1794, but learned from the Manusmrti "that system of duties, religious and civil, and the law in all its branches, which the Hindus firmly believe to have been promulgated in the beginning of time by menu" (ibid.: viii).91 [Even though he was to be proved wrong on that account, Jones believed that the Manusmrti was composed as early as 1280 B.C.]

The Manusmrti continued to attract attention after 1794.92 [Jones' translation was reprinted, in England, in 1796, and translated into German in 1797. It was again reprinted, with an edition of the Sanskrit text and new annotations, by Graves Chamney Haughton, in 1825. For these and later editions, see Garland Cannon, Sir William Jones: A Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1979), 32-34. The first edition of Manu in France, by Auguste Loiseleur Deslongchamps, appeared in 1830; his 1833 translation was reprinted in 1840.] Yet, more than a half century would pass before the publication of the translation of a second Dharmasastra, the one attributed to Yajnavalkya. This translation was not in English but in German, and it was not produced to be of any service whatever to the administration of justice in India. As the translator, Adolf Friedrich Stenzler (1849: iii), pointed out, the British had turned away from the ancient Dharmasastras to other Sanskrit texts that were totally devoted to law and, consequently, more important for the administration of justice.93 [English translations of other ancient dharma texts appeared more than one century after Hastings' Plan. Except for a preliminary translation, from manuscripts, of the Naradasmrti by Julius Jolly (1876), most translations were published, at Oxford, in Max Muller's The Sacred Books of the East: Apastamba and Gautama (vol. 2, Buhler 1879), Visnu (vol. 7, Jolly, 1880), Vasistha and Baudhayana (vol. 14, Buhler, 1882), Manu (vol. 25, Buhler, 1886), Narada and Brhaspati (vol. 33, Jolly, 1889). Many other Dharmasastras, some of them known only from quotations in the commentaries, still remain untranslated.]

Stenzler noted that the time had come to make a scholarly study of the entire corpus of Indian law books. He submitted that, once the relative chronology of the texts was established, "[a] comparative study of all these texts is bound to lead to results which will contribute not a little to our understanding of the development of life in India" (Stenzler 1849: Vorrede, iii). One year later he argued even more forcefully and in greater detail that "[ i]t is to be expected that a more accurate knowledge of this richly developed branch of Indian literature, which draws on the most varied situations of life, will provide true insights into the history of the Indian people" (Stenzler 1850: 237). Stenzler thus formulated, for the Dharmasastra literature as a whole, the same expectation voiced for Manu by Jones much earlier, namely that these texts provide a true picture of the law of the land, i.e., of law as it was actually practiced in classical India.

The same idea appears again and again in later scholarly literature. I will restrict myself to quoting some of its major proponents. Friedrich Max Muller noted, at least as far as the prose Dharmasutras -- which he considered to be older than the versified Dharmasastras -- are concerned, that "[t]hey are of great importance for forming a correct view of the old state of society in India" (1859: 134).94 [There is a potentially misleading statement by Georg Buhler concerning Muller's views on the versified Dharmasastras. In connection with the Dharmasutras attributed to Apastamba, Buhler noted: "Their discovery enabled Max Muller, nearly thirty years ago, to dispose finally of the Brahmanical legend according to which Hindu society was supposed to be governed by the codes of ancient sages, compiled for the express purpose of tying down each individual to his station, and of strictly regulating even the smallest acts of his daily life" (Sacred Books of the East, 2: ix). What Muller really meant is that the versified sastras, which he considered to be more recent than the prose sutras, should not be used to reconstruct life in earlier Vedic times, for "they likewise admitted the rules and customs of a later age" (1859: 61). Muller did not say that the versified Dharmasastras were unreliable sources as far as their own times were concerned.] In 1868 Albrecht Weber expressed the hope that the publication of more dharma texts "would spread the kind of light which we can as yet hardly fathom" (Weber 1868: 815-117). Arthur Cole Burnell realized that there were considerable differences between the various Dharmasastras, but that was "no reason to believe that these works do not represent the actual laws which were administered" (1868: xiii).95 [This is all the more remarkable since Burnell was a close friend of James H. Nelson whose -- very different -- views on the Dharmasastras will be discussed later.] Leopold von Schroeder spoke of the Indian law books as being "of the highest importance for the knowledge of public and private relations, nay of any aspect of Indian life and activity" (Schroeder 1887: 734). Willy Foy proposed to use the Dharmasastras to draw a picture of royal power which was to be "important for the cultural history of India" (Foy 1895: 4), and Joseph Dahlmann heralded the law books as "truly historical records."96 ["Der Gesellschaftskunde erschliessen sich seit dem neunten Jahrundert v. Chr. im Bereiche des indischen Rechts wahrhaft geschictliche Quellen" [Google translate: Social studies have been opening up since the ninth century BC. In the realm of Indian law, truly historical sources] (Dahlmann 1899: 48). Dahlmann opposed the opinion of Senart; see below.]

Perhaps most important of all is that Julius Jolly's classic work on Hindu Law and Custom (1928 [1896]) and Pandurang Vaman Kane's monumental History of Dharmasastra (1930-62) were based on the assumption that the legal precepts contained in the texts were real,97 [Jolly refers to the sutras and the sastras as two "stages of Indian legal literature" (2). In Kane's third volume (1946), which is more specifically devoted to the legal aspects of dharma, he says: "This work in intention and scope ... concerns itself with pointing out what the law of the Smrtis and writers of medieval digests was" (544).] and that the two standard treatises of modern Hindu law confirm in their introductions that "[t]here can be no doubt that the smriti rules were concerned with the practical administration of the law" (Aiyar 1950: 2), and, in connection with Manu, speak of "the systematic and cogent collection of rules of existing law that it gave to the people with clarity and in language simple and easy of comprehension" (Desai 1970 [1966]: 20).

Yet, not everyone agreed. I will mention only in passing the opinion of Thomas Babington Macaulay that "neither as the languages of law nor as the languages of religion have the Sanskrit and Arabic any peculiar claim to our encouragement," and his expectation that, once the Indian Law Commission of 1833, on which he sat, had completed its task, "the shastras and the hadith will become useless" (cited in Phillips 1977: 1411, 1410).98 [Macaulay wished to go even further: "I would strike at the root of the bad system which has hitherto been fostered by us. I would at once stop the printing of Arabic and Sanskrit books" (Phillips 1977: 1412).]

Far more important was the proclamation, as early as 1861, of no less a personage than Sir Henry Sumner Maine that

[t]he Hindoo Code, called the Laws of Menu, which is certainly a Brahmin compilation, undoubtedly enshrines many genuine observances of the Hindu race, but the opinion of the best contemporary orientalists is, that it does not, as a whole, represent a set of rules ever actively administered in Hindostan. It is, in great part, an ideal picture of that which, in the view of the Brahmins, ought to be the law.99 [On Maine, see J. Duncan M. Derrett 1959. It is not clear to me whom Maine means by "the best contemporary orientalists." According to Derrett (42) "much of what turns up in Maine" was supplied by James Mill's "disastrous" History of British India (first published in 1817). As far as I know Mill did not make any statement similar to Maine's. Speaking about the "endless conceits" of Sanskrit grammatical literature, he said, thought, that "[ i]t could not happen otherwise than that the Hindus should, beyond other nations, abound in those frivolous refinements which are suited to the taste of an uncivilized people. A whole race of men were set apart and exempted from the ordinary cares and labours of life, whom the pain of vacuity forced upon some application of mind, and who were under the necessity of maintaining their influence among the people, by the credit of superior learning, and, if not by real knowledge, which is slowly and with much difficulty attained, by artful contrivances for deceiving the people with the semblance of it. This view of the situation of the Brahmans serves to explain many things which modify and colour Hindu society" (reprint from the 2nd edition, 1972 [1820]: 1.383-384). Mill also agreed with Francis Wilford that the king lists in the Puranas "are the creation of the fancies of the writers" (ibid.: 464).] (14)

Maine put the blame squarely on William Jones: "The opinions of Sir William Jones produced great effects both in the East and in the West... The Anglo-Indian Courts accepted from the school of the Sanscritists which he founded the assertion of his Brahmanical advisers, that the sacred laws beginning in the extant book of Manu were acknowledged by all Hindus to be binding on them" (1975 [1886]: 6).100 [At least this much is clear, that Jones, the "orientalist," was one of the principal betes noires of James Mill.]

Among the chief advantages which the Twelve Tables and similar codes conferred on the societies which obtained them,011 was the protection which they afforded against the frauds of the privileged oligarchy and also against the spontaneous depravation and debasement of the national institutions. The Roman Code was merely an enunciation in words of the existing customs of the Roman people. Relatively to the progress of the Romans in civilisation, it was a remarkably early code, and it was published at a time when Roman society had barely emerged from that intellectual condition in which civil obligation and religious duty are inevitably confounded. Now a barbarous society practising a body of customs, is exposed to some especial dangers which may be absolutely fatal to its progress in civilisation. The usages which a particular community is found to have adopted in its infancy and in its primitive seats are generally those which are on the whole best suited to promote its physical and moral well-being; and, if they are retained in their integrity until new social wants have taught new practices, the upward march of society is almost certain. But unhappily there is a law of development which ever threatens to operate upon unwritten usage. The customs are of course obeyed by multitudes who are incapable of understanding the true ground of their expediency, and who are therefore left inevitably to invent superstitious reasons for their permanence. A process then commences which may be shortly described by saying that usage which is reasonable generates usage which is unreasonable. Analogy, the most valuable of instruments in the maturity of jurisprudence, is the most dangerous of snares in its infancy. Prohibitions and ordinances, originally confined, for good reasons, to a single description of acts, are made to apply to all acts of the same class, because a man menaced with the anger of the gods for doing one thing, feels a natural terror in doing any other thing which is remotely like it. After one kind of food has been interdicted for sanitary reasons, the prohibition is extended to all food resembling it, though the resemblance occasionally depends on analogies the most fanciful. So, again, a wise provision for insuring general cleanliness dictates in time long routines of ceremonial ablution; and that division into classes which at a particular crisis of social history is necessary for the maintenance of the national existence degenerates into the most disastrous and blighting of all human institutions—Caste. The fate of the Hindoo012 law is, in fact, the measure of the value of the Roman code. Ethnology shows us that the Romans and the Hindoos sprang from the same original stock, and there is indeed a striking resemblance between what appear to have been their original customs. Even now, Hindoo jurisprudence has a substratum of forethought and sound judgment, but irrational imitation has engrafted in it an immense apparatus of cruel absurdities. From these corruptions the Romans were protected by their code. It was compiled while the usage was still wholesome, and a hundred years afterwards it might have been too late. The Hindoo law has been to a great extent embodied in writing, but, ancient as in one sense are the compendia which still exist in Sanskrit, they contain ample evidence that they were drawn up after the mischief had been done. We are not of course entitled to say that if the Twelve Tables had not been published the Romans would have been condemned to a civilisation as feeble and perverted as that of the Hindoos, but thus much at least is certain, that with their code they were exempt from the very chance of so unhappy a destiny.

--Ancient Law: Its Connection to the History of Early Society, by Sir Henry James Sumner Maine

Maine's view found support from various quarters. Both for practical and academic reasons. James Henry Nelson who was active in various locations in South India, was unhappy administering the Hindu law created by Jones and other Sanskrit scholars in faraway Calcutta (on Nelson see Derrett 1961: 354-372). He raised the question. "Has such a thing as 'Hindu Law' at any time existed in the world? Or is it that 'Hindu Law' is a mere phantom of the brain, imagined by Sanskritists without law and lawyers without Sanskrit?" (Nelson 1877: 2).

Nelson questioned not only the reliability of the Manusmrti as a source of law, but the existence of Manu himself: "If he at any time existed ... , which is most unlikely, Manu cannot be supposed to have set laws to India" (4).

In early texts, it refers to the archetypal man, or to the first man (progenitor of humanity). The Sanskrit term for 'human', मानव (IAST: mānava) means 'of Manu' or 'children of Manu'. In later texts, Manu is the title or name of fourteen mystical Kshatriya rulers of earth, or alternatively as the head of mythical dynasties that begin with each cyclic kalpa (aeon) when the universe is born anew. The title of the text Manusmriti uses this term as a prefix, but refers to the first Manu – Svayambhuva, the spiritual son of Brahma...

In Vishnu Purana, Vaivasvata, also known as Sraddhadeva or Satyavrata, was the king of Dravida before the great flood. He was warned of the flood by the Matsya (fish) avatar of Vishnu, and built a boat that carried the Vedas, Manu's family and the seven sages to safety, helped by Matsya. The tale is repeated with variations in other texts, including the Mahabharata and a few other Puranas. It is similar to other flood such as that of Gilgamesh and Noah.

-- Manu, by Wikipedia

And he continued:

Assuming however, for argument's sake that a man named Manu once existed and set laws to men ..., it must ... be conceded that he set them only to certain masses of men abiding in and about part of the Punjab, namely to certain Arya tribes or families and in some instances also to certain tribes or families styled Sudras. Now: whether a remnant of any one of those tribes or families still exists in any part of India of course is exceedingly doubtful. And whether a remnant of any one of them existed at any time within the limits of the Madras Province, except perhaps on the Western Coast, is still more doubtful.101[John D. Mayne, whose Treatise of Hindu Law and Usage 1878) was first published one year after Nelson's View, admits that "[ i]n much that he says I thoroughly agree with him." Yet, "it seems to me that the influence of Brahmanism upon even the Sanskrit writers has been greatly exaggerated, and that those parts of the Sanskrit law which are of any practical importance are mainly based upon usage, which, in substance, though not in detail, is common to both the Aryan and non-Aryan tribes" (vii).] (Ibid.: 4-5)

[A]t the end of his letter Mr. Innes shows plainly that, at all costs, the Madras High Court intends to continue to perform its self-imposed duty of civilising the 'lower castes' of Madras, that is to say, the great bulk of its population, by gradually destroying their local usages and customs, the safety of which the royal proclamation of November 1, 1858, by express words, guarantees. It was Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen who said, 'We disclaim alike the right and desire to impose our convictions on any of our subjects.... We will that generally in framing and administering the law due regard be paid to the ancient rights, usages, and customs of India.' Mr. Innes, however, as the representative of the Madras High Court, has announced (at p. 110): —

'To adopt Mr. Nelson's suggestions, whether as regards the higher or lower castes, would commit us to chaos in the matter of the Hindu law we are now called on to administer. What is contemplated would result in our abdicating the vantage ground we have occupied for nearly a century, in which, if we continue to hold it, we may hope gradually to remove the differentiations of customary law, and bring about a certain amount of manageable uniformity. It would be to commit us to the investigation and enforcement of an overwhelming variety of discordant customs among the lower castes, many of them of a highly immoral and objectionable character, which if not brought into prominence and sanctioned by judicial recognition, will gradually give place to the less objectionable and more civilised customs of the superior castes.'

-- Indian Usage and Judge-Made Law in Madras, by J.H. Nelson, M.A.

Arguments against the Dharmasastras also came from one eminent European Sanskrit scholar, the Frenchman Emile Senart. In Les castes dans l'Inde: Les faits et le systeme, Senart was less concerned with the legal sections of the Dharmasastras than with their presentation of the four-fold caste system: Brahmin, Ksatriya, Vaisya, Sudra. Yet, the result of his study was damaging to the law books as a whole. Senart contrasted the infinitely complex modern caste system with the relatively simple and structured way in which it appears in the Dharmasastras and other classical texts such as the epics. He submitted that the present-day complexities must, to a certain degree, go back as far as the time of the ancient texts, and concluded: "What seems certain to me is that neither the epics nor, above all, the Smrtis should be accepted as straightforward and faithful witnesses [temoins integres et fidels] of contemporary data"102 [Senart's view was criticized by Hermann Oldenberg (1897: 268), and by Dahlmann (1899: 49-50): "Der ganze Charakter des aus der Wirklichkeit des Lebens hervorgehenden Rechts schliesst aber jene bewusste Falschung auf das entschiedenste aus".] (1927 [1896]: 11).

Finally, according to Govinda Das, an Indian Sanskrit scholar, "[ i]t is a profound error to regard the Smritis as complete codes of law or as getting all their 'rules' rigidly enforced by the political authorities of their times" (Das 1914: 8), And he concluded a long discussion with the question: "After all this can one seriously contend that Hindu law was in the main ever more than a pious wish of its metaphysically-minded, ceremonial-ridden priestly promulgators, and but seldom a stern reality?" (16)

In other words, according to a number of reputable scholars the ancient Indian Dharmasastras duly and truly described the law of the land; according to other equally reputable scholars they were the product of pure brahmanical fantasy and they tell us only what the Brahmin caste would have liked the law of the land to be. The dilemma this situation makes for the historian of classical Hindu law is obvious. Either the information at his disposal is infinitely broad and detailed, allowing him to reconstruct both substantive and adjective law in ancient India with a high degree of accuracy; or the entire corpus of classical Indian law books is untrustworthy and should be dismissed as a source of information on what really was the law of the land. I will suggest in the following pages that there is a better and more productive approach to understanding the nature and meaning of the Indian Dharmasastras than asking the single question whether or not they describe the law of the land and, depending on the answer, concluding that they are or are not reliable law books.103 [This essay supersedes my earlier attempts (1957, 1967, and 1978) at understanding the nature of the Dharmasastra.]

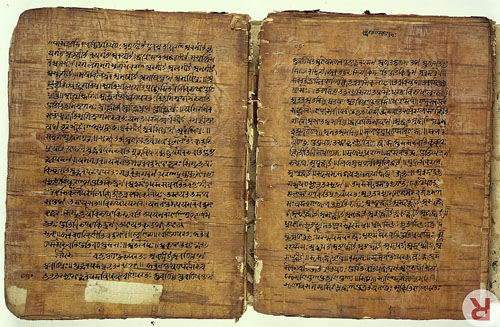

By way of introduction I would like to remind the reader of the signal importance, in India, of memorization. It is well known that the entire system of education in classical, and to a certain extent in modern India, was and is based on learning by rote.104 [Hence, the emphasis on mnemotechnic devices in books on Indian education. See, for example, Mookerji 1969: 211-215; Rocher 1994.] From a very early age onward Indians were -- and still are -- trained to memorize sentences, passages, even books on all kinds of topics, whether learned or trivial.

Numerous Western visitors to India have expressed their amazement at this phenomenon, but I wish to concentrate on two such visitors because they reported not only on the mnemonics of Indians but also on law and law books.

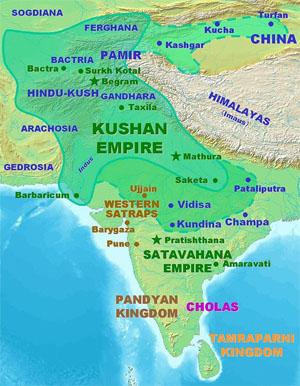

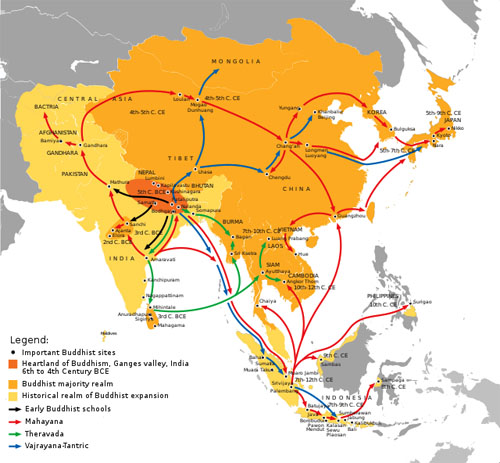

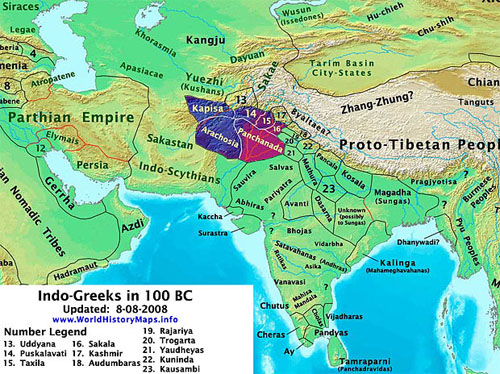

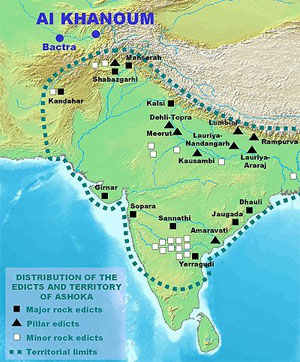

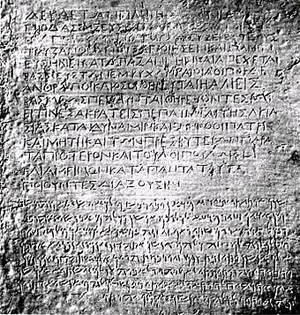

In the first place there is a statement attributed to Megasthenes, the ambassador whom Seleucus Nicator, one of the successors of Alexander the Great, sent to Candragupta, the king of the Mauryas. Megasthenes visited India, perhaps several times, ca. 300 BC. A fragment of his lost Indica, as recorded in Strabo's Geography, relates the ambassador's surprise that there was so little crime among the Indians, "and that too among a people who use unwritten laws only." "For," he continues, "they have no knowledge of written letters, and regulate every single thing from memory" (Strabo in Jones 1930: 15. 1.53, 86-89). Megasthenes must have seen an Indian court of law at work. As a Greek, he was puzzled that the judge did not use any law books; as a Greek, he drew the logical conclusion that, if the judge did, i.e. , had to do, without a law book, first, the Indians did not have law books, and, second, they must not have known the art of writing.

Megasthenes was wrong as far as the latter part of his conclusion is concerned. We know that there was writing in India in the time of Megasthenes. Also, one of his predecessors, Nearchus, Alexander's friend and companion, reported that, according to some, Indians "write missives on linen cloth that is very closely woven" (ibid.: 15.1.67, 116-117) . But Nearchus did confirm Megasthenes' conclusion that the Indians had no law books: "Nearchus ... declares ... [t]hat their laws, some public and some private, are unwritten" (ibid.: 15.1.66, 114-115).

Nearchus' and, far more so, Megasthenes' statements on the absence of law books have attracted much scholarly attention. Knowing, as we do, that the Indians had many Dharmasastras, some of which may go back to 500 BC, the Greek observers must have been misled. According to one explanation, the ancient Indians did have written law books, but they were not needed in the law courts because the judges had memorized them (Schwanbeck 1846: 50-51, n. 48).105 [Schwanbeck adds an alternative explanation, namely that "for some reason" (quadam causa) Indians call their law books smrti (=mnene, memory). Cf. Rocher 1956-1957, also included in the present volume.] In the opinion of the latest editor of Megasthenes' fragments, "the laws were indeed mainly unwritten; it was not customary [for Indians] to reduce their sacred books (and the Dharmasastras belong to them) to writing" (Timmer 1930: 245). Others, finally, dismissed the statements on the absence of law books in ancient India as one of the many instances "in which the ignorance of the classical writers is difficult to explain" (Majumdar 1960: xix).

At this point I will introduce a document produced by the second visitor to India whom I announced earlier. It is a letter, sent to a prominent jurist in Paris, by a French Jesuit missionary, from Pondicherry in South India, in 1714. It has been published in several editions of the Lettres edifiantes et curieuses, the vast collection of letters written from various Jesuit missions. The writer of the letter is Father Jean Venant Bouchet; except for an introductory paragraph, the long letter is entirely devoted to the administration of law as Bouchet saw it in India, some two thousand years after Megasthenes.106 [Although the letter has not remained unnoticed, it has not received the attention it deserves. J.H. Nelson referred to it, especially in "Hindu Law at Madras," (1881). For an annotated English translation, see Rocher, "Father Bouchet's Letter," 1984b.] Yet, some two millennia after Megasthenes, Father Bouchet's first sentence sounds uncannily familiar: "They have neither codes or digests, nor do they have any books in which are written down the laws to which they have to conform to solve the disputes that arise in their families" (Rocher 1984b: 18). In other words, as astute and inquisitive an observer as Father Bouchet did not see any Hindu law books in 1714, either.

The observations on the absence of law books in settling disputes among Hindus, made by two foreigners visiting India at an interval of two thousand years, raise a number of questions. First, what did the Hindu judicial authorities use instead of law books to settle disputes? Second, where were the Dharmasastras, composed from ca. 500 BC onward, of which neither Megasthenes nor Bouchet saw any trace? Third, and most important, what are the Dharmasastras which William Jones accepted as representing the law of the land, and which Henry Sumner Maine dismissed as brahmanical fantasy?

On the first question Bouchet leaves no doubt. Echoing Megasthenes' brief remark that unwritten laws among Indians did not entail a higher degree of lawlessness, Bouchet explains, in far greater detail, that absence of law books did not in any way imply absence of justice.

The equity of all their verdicts is entirely founded on a number of customs which they consider inviolable, and on certain usages which are handed down from father to son. They regard these usages as definite and infallible rules, to maintain peace in the family and to end the suits that arise, not only among private individuals, but also among royal princes. (Ibid.: 18-19)

Bouchet makes it clear that some of these customs were "accepted in all castes," such as the belief that children of two brothers or of two sisters are brothers whereas children of a brother and a sister are cousins, with the result that the latter can intermarry, the former cannot. Other customs on the contrary, are valid within a particular caste only, and customs may vary from caste to caste: "As soon as it has been proven that someone's claim is based on a custom that is followed within the caste, and on common usage, that is enough" (ibid.: 19). Also, whereas the village head is the natural judge in suits arising in his village, "[ i]f it is a question related to caste, it is the heads of the castes who decide" (ibid.: 31).

In connection with the fact that these customs were unwritten, Bouchet relates how a European gentleman suggested to him that there must be much injustice in a system in which, unlike Europe, judges were not held in check by written laws.

I shall not examine here the enormous advantages one pretends to derive from this prodigious multitude of laws; but it seems to me that the Indians are not really to be blamed for not having cared to codify their customs. After all, is it not enough that they possess them perfectly? And, if this is so, what is the good of books? In reality, nothing is better known than these customs: I have seen children ten or twelve years old who knew them perfectly. (Ibid .: 21)

Finally, as to the form in which the customs are memorized and transmitted, Bouchet uses, interchangeably, the terms "maxims," "proverbs," and "'quatrains," the latter of which seems to indicate that they were in verse. At one point he more specifically refers to the fact that "they quote a quatrain which is to them more or less what Pibrac's quatrains are to us" (ibid.: 28-29).107 [This is a reference to the collection of moralizing quatrains by Gui du Faur, Seigneur de Pibrac (1529-1584). First published in 1574, they became very popular, and went through numerous editions, with additions.] Bouchet quotes and comments on several of these maxims. For instance:

When there are several children in a family, the males alone inherit; the girls have no claim at all to the inheritance. (Ibid.: 38-40)

If the property has not been divided upon the death of the father, anything that has been acquired by one of the children shall be entered into the common stock and divided equally. (Ibid.: 42-43)

Adopted children share equally in the estate with the children of their adoptive fathers and mothers. (Ibid.: 43-45)

The father shall pay all debts contracted by his children; children shall equally pay all debts of their father, (Ibid,: 47-48)

Bouchet's letter ends as follows:

It is these general maxims, Sir, that serve as substitutes for laws in India; it is these that are followed in the administration of justice. There are other more specific laws which are applicable within each caste. Since these would lead me too far, they shall be the subject of another letter which I will be honored to write you. (Ibid.: 48)

Unfortunately, this other letter does not seem to have been written.

The main conclusion to be drawn from Bouchet's letter is that in the area of India with which he was familiar, and probably in most other areas as well, law was administered on the basis of unwritten maxims, which were transmitted from generation to generation, in the local vernaculars, some of them applicable to the population of the area generally, others to specific groups such as the members of a particular caste only. I often wonder whether, had Bouchet also provided the readings of these maxims in the original vernacular, there would not be ample opportunity to compare them with specific verses, "quatrains." slokas, in the written, Sanskrit Dharmasastras.108 [For example, Bouchet's first maxim closely resembles a half stanza preserved in the Baudhayanadharmasutra (2.2.5.46) which declares women to be adaya "without a share," an idea which also occurs in earlier Vedic texts (Taittiriyasamhita 6.5.8.2: women are adayada). Cf. even Rgveda 3.31.2: "The son-of- the-body did not share the inheritance with his sister" (transl. Geldner). The principle referred to in the fourth maxim quoted above is well known in the Dharmasastras, and corresponds to what in Anglo-Indian law was to be called the pious obligation.]

Turning to the second question I asked earlier, it is quite clear that the Dharmasastras were unknown to Bouchet's informants. In fact, they were unaware of, and opposed to, even their own maxims being preserved in writing. Bouchet reports that he inquired why they had not collected their customs in books to consult if needed. "Their answer is that, if these customs were entered into books, only the learned would be able to read them, whereas, if they are handed down orally from generation to generation, everyone is fully informed" (Rocher 1984: 20).

Yet, there are indications that the Dharmasastras existed in written form perhaps even at a relatively early date. According to a verse in the Naradasmrti the sastra is one of the eight "limbs" of legal procedure, together with the king or chief judge, the assessors. the accountant, the scribe, gold, fire, and water (transl. Jolly, Introduction, 1.16). A sloka "quatrain" attributed to the lost Brhaspatismrti 1.17 prescribes that "the king should cause gold, fire, water, and the codes of the sacred law (Dharmasastras, plural) to be placed in the midst of them, i.e., the members of the court], also (other) holy and auspicious things."109 [I must note, though, that this verse is attested in one later digest, Devannabhatta's Smrticandrika, only.] Two other verses attributed to Brhaspati also provide the earliest interpretation and reconciliation of the conflicting views on levirate appearing in the preserved Manusmrti (to which I will return later) (transl. Jolly 24, 16-17).

Finally, even Bouchet's informants were vaguely aware of certain laws inscribed on mysterious copper plates, and guarded with care by learned Brahmins in a big tower in the city of Conjeeveram. However, "[s]ince the Moors have nearly entirely destroyed this large and famous town, no one has been able to find out what happened to these plates; the only thing we know is that they contained everything that relates to any caste in particular and the relations which different castes should observe among one another" (Rocher 1984: 20).

In other words, law books, even law books in the vernacular, and, a fortiori, Sanskrit law books, were the preserve of the learned, of the select few who were able to read -- and write -- them. In ordinary legal practice everyone used detached, unconnected maxims.

I can now return to the third question I raised: what exactly are the learned, written Dharmasastras?110 [I wish to remind the reader that the conclusions that will follow relate to the ancient Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras only (cf. note 3). The commentaries, which are also part of the Dharmasastra literature in its broader sense, raise problems of a totally different nature. See, e.g., my "Schools of Hindu Law," 1972, also included in the present volume.] To answer this question I must refer to one of their most salient features, which has helped me greatly to reach the conclusion I present in this essay. The point is that there are, in the Dharmasastras, some strange and troubling contradictions, not only between different Dharmasastras (Kane 1930-62: 3.866-870), but within one and the same text as well.

For instance, in Manu's section on inheritance there is a verse (9.104) to the effect that, after the death of both parents, the sons get together and divide the inheritance equally. The next verse (9.105), without any transition whatever, enjoins that, after the death of both parents, the eldest son gets everything and the younger sons continue to live under him as they did under their father. A few verses are then dedicated to praising the greatness of an eldest son. And then, again without transition, Manu 9.112 declares that, when both parents are deceased, the inheritance is divided, but in such a way that the eldest son receives an additional share of 5 percent, the next son an extra share of half of that, etc. In other words, within the brief span of nine verses Manu offers three different ways for sons to deal with the parental inheritance.

Elsewhere Manu 9.57 informs us that, when a husband dies without having a son, his younger brother shall substitute for him and have a son with his elder brother's widow. The text goes into detail on how and when the intercourse shall take place, on how the parties shall behave, etc. All of this clearly indicates that Manu is familiar with the custom of levirate which is also known in other legal systems.111 [The son born of this kind of union is called ksetra-ja "field-born," i.e., born from seed sown in someone else's field. Manu describes his share in the inheritance at 9.120-121.] But Manu 9.64 then goes on to say that a widow should never have intercourse with anyone other than her husband, including her brother-in-law. Such behavior, the text adds is pasudharma "dharma of pasus, beasts" (9.66).112 [On the history of niyoga, from Vedic times onward, see Emeneau and van Nooten 1991: 481-494.]

Contradictions of this kind occur throughout the Manusmrti, but they are particularly obvious in the ninth book devoted to family law (for other examples, see Lingat 1973 [1967]: 182). Scholars who believed that the Dharmasastras were codices representing the law of the land were forced to look for justifications. It has been suggested that contradictory rules in the Dharmasastras, as in all revealed Hindu texts, must be interpreted as options (Buhler 1886: xcii-xciii).113 [Hence Buhler introduces Manu 9.105 which makes the entire paternal property devolve on the eldest son with the word "[Or]" which is not present in the Sanskrit text. He also offers an alternate explanation: the fact that the versified Manava-Dharmasastra is, in his view, a recast of a lost prose Manavadharmasutra "alone is sufficient to account for contradictions."] According to Lingat, "[ i]t emerges from these texts that the author of the Code of Manu was hostile" to a number of practices, "but he was confronted by customs too deeply rooted for prohibition to be efficacious. All he could do was to try to discredit them" (1973: 182).114 [According to Derrett too, "the Rishis are found to acknowledge as existing and worthy of regulation a few institutions which affronted their refined moral senses" (Derrett 1978: 52) and he refers to niyoga as a prime example. Seventy years earlier Joseph Kohler used Manu's passage on niyoga as "a well-known example" of the fact that lex posterior derogat priori is a Western, not an Eastern principle (Kohler 1910: 242).] In connection with levirate in particular, it has been suggested by some that Manu intended the practice to be allowed for sudras, but forbidden for the three higher classes.115 [This interpretation based on Manu 9.66 ("the practice is reprehended by the learned of the twice-born classes"), appears as early as Eduard Gans, Das Erbrecht in weltgeschichtlicher Entwickelung (1824-1825: 1.77), and has often been repeated.] Most other explanations tacitly assume that Hindu society moved from a stage in which niyoga was common practice to a stage in which it was considered taboo.116 [Typically, see Ludwik Sternbach's introduction to Chakradar Jha's History and Sources of Law in Ancient India (1987: vii). I should note that this is also the traditional Indian interpretation, exhibited for the first time in the passage from the Brhaspatismrti to which I referred earlier: niyoga was allowed in the three earlier world ages, but is forbidden in the present, decadent Kali age.] The verses prohibiting levirate, therefore, "are probably a later addition" (Burnell 1884: E.W. Hopkins' note at 255); they have "obviously been tacked on ... at a time when the practice of Niyoga had fallen into disuse" (Jolly 1885: 48), the practice having to be described nevertheless as "being part of the traditional Dharma" (Holly 1928 [1896]: 121).

Notwithstanding these and other ingenious efforts, by the commentators first, by modern scholars later, to account for the contradictions in the Dharmasastras, it is obvious that books that prescribe three different ways of dealing with paternal property, books that first prescribe levirate and then forbid it, are hardly usable in legal practice.

The important but easily overlooked point is that it is normal, that it is a premise, in Hinduism, that what is dharma for one is different from what is dharma for another. Dharma, basically, is accepted custom (acara), i.e., custom accepted in a region, in a village, even in a caste or a sub-caste within a village. But all these different customs are dharma in their own right.117 [Marc Galanter rightly pointed out that this is one of the main differences between traditional and modern Indian law which "put[s] forth claims in terms of general rules applicable to the whole society" ("Hinduism, Secularism, and the Indian Judiciary," 1971; reprinted in Law and Society, in Modern India, 1989: 237).] With the single and relatively vague proviso that "they should not be contrary to the Veda," the Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras themselves unanimously accept the validity of practices recognized within a region, a caste, or a family; they provide that customs peculiar to cultivators, traders, herdsmen, money-lenders, artisans, etc., are binding on these various groups (see Kane 193(k;2: 3.857-863). In the case of inheritance in particular, a verse in Kautilya's Arthasastra 3.7.40 prescribes: "whatever be the customary law (dharma) of a region, a caste, a corporation or a village, in accordance with that alone shall he [i.e., the judge] administer the law of inheritance" (Kangle 1963: 249).118 [A nearly identical verse is transmitted as part of the lost Katyayanasmrti (Kane 313 [884A]).

In actual dispute settlement each of these customs, or sets of customs, was applied, consistently, in the appropriate circumstances. Members of one area or one group always divided paternal property equally, others unequally, others again did not divide it at all. Among some there was levirate, among others there was not.119 [On the practice of levirate in modern India, see Emeneau and van Nooten 1991: 487, based primarily on Karve 1965.] In India's largely oral culture these area-specific or group-specific rules were transmitted in the form of Memorialverse, in the vernacular; and they remained unwritten.120 [I borrowed the term Memorialverse in the context of Sanskrit dharma literature from an article by Luders 1917; reprinted in Philologica Indica. Ausgewahlte kleine Schriften, 1940.] The composers of the Dharmasastras, on the other hand, compiled treatises on dharma, on anything they considered worthy of being recorded as dharma with some people, somewhere. They gathered that information in books, in the language of the learned, Sanskrit.

What I wanted to show in this essay is that it is possible, in a culture in which memorization plays an important role in day-to-day life, to have books, the Dharmasastras, that are legal fiction because they were divorced from the practical administration of justice -- the role they were given in 1772 121 [The question whether Hastings' decision was right or wrong has been the object of much scholarly discussion. Derrett refers to K.V. Venkatasubramania Iyer, according to whom Hastings misunderstood what function the sastra had, when he made it the sole source of law, and adds: "this is not quite certain, but the fact that the doubt can arise is significant" (1968: 288). K. Lipstein's conclusion that the Plan of 1772 "led to the application of rules which were either obsolete or never in force" has to be seen against the background of his opinion that the sastra "was never more than a fiction" (1957: 281).] -- but which are not for that reason the product of brahmanical fantasy.122 [The argument of "brahmanical fantasy" has been used in other areas as well. Cf. Mill's statement on the Brahmins above. Also, in connection with the Dhatupatha, a list of some two thousand verbal roots of which more than half have not been met with in Sanskrit literature, it has been suggested that it was "concocted" by the Indian grammarians (Whitney 1884; reprinted in Staal 1992: 142). In fact, the Indian pandits have been accused of inventing the Sanskrit language (Dugald Stewart and Christoph Meiners, quoted in Rosane Rocher 1983: 78).] They are books of law -- rather, books of laws -- containing "a mass of floating verses of rules and observations" that were, indeed, at some time and in some place "governing the life and conduct of people" (Raghavan 1962: 2.335).

The main thing which makes of the grammarians' Sanskrit a special and peculiar language is its list of roots. Of these there are reported to us about two thousand, with no intimation of any difference in character among them, or warning that a part of them may and that another part may not be drawn upon for forms to be actually used; all stand upon the same plane. But more than half — actually more than half — of them never have been met with, and never will be met with, in the Sanskrit literature of any age. When this fact began to come to light, it was long fondly hoped, or believed, that the missing elements would yet turn up in some corner of the literature not hitherto ransacked; but all expectation of that has now been abandoned. One or another does appear from time to time; but what are they among so many? The last notable case was that of the root stigh, discovered in the Maitrayani-Sanhita, a text of the Brahmana period; but the new roots found in such texts are apt to turn out wanting in the lists of the grammarians. Beyond all question, a certain number of cases are to be allowed for, of real roots, proved such by the occurrence of their evident cognates in other related languages, and chancing not to appear in the known literature; but they can go only a very small way indeed toward accounting for the eleven hundred unauthenticated roots. Others may have been assumed as underlying certain derivatives or bodies of derivatives — within due limits, a perfectly legitimate proceeding; but the cases thus explainable do not prove to be numerous. There remain then the great mass, whose presence in the lists no ingenuity has yet proved sufficient to account for. And in no small part, they bear their falsity and artificiality on the surface, in their phonetic form and in the meanings ascribed to them; we can confidently say that the Sanskrit language, known to us through a long period of development, neither had nor could have any such roots. How the grammarians came to concoct their list, rejected in practice by themselves and their own pupils, is hitherto an unexplained mystery. No special student of the native grammar, to my knowledge, has attempted to cast any light upon it; and it was left for Dr. Edgren, no partisan of the grammarians, to group and set forth the facts for the first time, in the Journal of the American Oriental Society (Vol. XI, 1882 [but the article printed in 1879], pp. 1-55), adding a list of the real roots, with brief particulars as to their occurrence.1 [I have myself now in press a much fuller account of the quotable roots of the language, with all their quotable tense-stems and primary derivatives — everything accompanied by a definition of the period of its known occurrence in the history of the language.] It is quite clear, with reference to this fundamental and most important item, of what character the grammarians' Sanskrit is. The real Sanskrit of the latest period is, as concerns its roots, a true successor to that of the earliest period, and through the known intermediates; it has lost some of the roots of its predecessors, as each of these some belonging to its own predecessors or predecessor; it has, also like these, won a certain number not earlier found: both in such measure as was to be expected. As for the rest of the asserted roots of the grammar, to account for them is not a matter that concerns at all the Sanskrit language and its history; it only concerns the history of the Hindu science of grammar. That, too, has come to be pretty generally acknowledged.1 [Not, indeed, universally; one may find among the selected verbs that are conjugated in full at the end of F. M. Muller's Sanskrit Grammar, no very small number of those that are utterly unknown to Sanskrit usage, ancient or modern.] Every one who knows anything of the history of Indo-European etymology knows how much mischief the grammarians' list of roots wrought in the hands of the earlier more incautious and credulous students of Sanskrit: how many false and worthless derivations were founded upon them. That sort of work, indeed, is not yet entirely a thing of the past; still, it has come to be well understood by most scholars that no alleged Sanskrit root can be accepted as real unless it is supported by such a use in the literary records of the language as authenticates it — for there are such things in the later language as artificial occurrences, forms made for once or twice from roots taken out of the grammarians' list, by a natural license, which one is only surprised not to see oftener availed of (there are hardly more than a dozen or two of such cases quotable): that they appear so seldom is the best evidence of the fact already pointed out above, that the grammar had, after all, only a superficial and negative influence upon the real tradition of the language.

-- The Study of Hindu Grammar and the Study of Sanskrit, by William Dwight Whitney

It has been already observed, that the Bedas are written in the Shanscrita tongue. Whether the Shanscrita was, in any period of antiquity, the vulgar language of Hindostan, or was invented by the Brahmins, to be a mysterious repository for their religion and philosophy, is difficult to determine. All other languages, it is true, were casually invented by mankind to express their ideas and wants; but the astonishing formation of the Shanscrita seems to be beyond the power of chance. In regularity of etymology and grammatical order, it far exceeds the Arabic. It, in short, bears evident marks that it has been fixed upon rational principles, by a body of learned men, who studied regularity, harmony, and a wonderful simplicity and energy of expression....

Though the Shanscrita is amazingly copious, a very small grammar and vocabulary serve to illustrate the principles of the whole. In a treatise of a few pages, the roots and primitives are all comprehended, and so uniform are the rules for derivations and inflections, that the etymon of every word is, with facility, at once investigated. The pronunciation is the greatest difficulty that attends the acquirement of the language to perfection. This is so quick and forcible that a person, even before the years of puberty, must labour a long time before he can pronounce it with propriety; but when once the pronunciation is attained to perfection, it strikes the ear with amazing boldness and harmony. The alphabet of the Shanscrita consists of fifty letters, but one half of these convey combined sounds, so that its characters, in fact, do not exceed ours in number.

-- History of Hindostan; From the Earliest Account of Time, To the Death of Akbar; Translated From the Persian of Mahummud Casim Ferishta of Delhi: Together With a Dissertation Concerning the Religion and Philosophy of the Brahmins; With an Appendix, Containing the History of the Mogul Empire, From Its Decline in the Reign of Mahummud Shaw, to the Present Times, by Alexander Dow.