Rama

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/26/21

Rama

The Ideal Man;[1] Embodiment of Dharma[2]

Member of Dashavatar

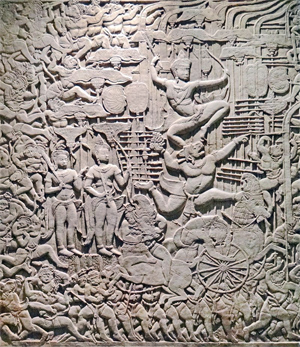

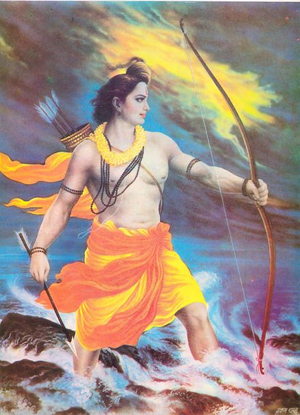

Lord Rama got fed up with asking a non-responding Varuna (God of the oceans) to help him and took up the Brahmastra.

Rama crossing the ocean to Lanka

Sanskrit transliteration Rāma

Affiliation: Seventh avatar of Vishnu, Brahman (Vaishnavism), Deva

Predecessor: Dasharatha

Successor: Lava

Abode: Vaikuntha, Ayodhya, and Saket

Weapon: Bow and arrows

Texts: Ramayana and its other versions

Gender: Male

Festivals: Rama Navami, Vivaha Panchami, Deepavali, Dusshera

Personal information

Born: Ayodhya, Kosala (present-day Uttar Pradesh, India)

Died: Sarayu River

Parents: Dasharatha (father)[3]; Kaushalya (mother)[3]; Kaikeyi (step-mother); Sumitra (step-mother)

Siblings: Shanta (sister); Lakshmana (half-brother); Bharata (half-brother); Shatrughna (half-brother)

Spouse: Sita[3]

Children: Lava (son); Kusha (son)

Dynasty: Raghuvanshi-Ikshvaku-Suryavanshi

Rama (/ˈrɑːmə/;[4] IAST: Rāma, Sanskrit pronunciation: [ˈraːmɐ] (About this soundlisten); Sanskrit: राम) or Ram,[α] also known as Ramachandra (/ˌrɑːməˈtʃʌndrə/;[6] IAST: Rāmacandra, Sanskrit: रामचन्द्र), is a major deity in Hinduism. He is the seventh avatar of Vishnu, one of his most popular incarnations along with Krishna, Parshurama, and Gautama Buddha. Jain Texts also mentioned Rama as the eighth balabhadra among the 63 salakapurusas.[7][8][9] In Sikhism, Rama is mentioned as one of twenty four divine incarnations of Vishnu in the Chaubis Avtar in Dasam Granth.[10] In Rama-centric traditions of Hinduism, he is considered the Supreme Being.[11]

Rama was born to Kaushalya and Dasharatha in Ayodhya, the ruler of the Kingdom of Kosala. His siblings included Lakshmana, Bharata, and Shatrughna. He married Sita. Though born in a royal family, their life is described in the Hindu texts as one challenged by unexpected changes such as an exile into impoverished and difficult circumstances, ethical questions and moral dilemmas.[12] Of all their travails, the most notable is the kidnapping of Sita by demon-king Ravana, followed by the determined and epic efforts of Rama and Lakshmana to gain her freedom and destroy the evil Ravana against great odds. The entire life story of Rama, Sita and their companions allegorically discusses duties, rights and social responsibilities of an individual. It illustrates dharma and dharmic living through model characters.[12][13]

Rama is especially important to Vaishnavism. He is the central figure of the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana, a text historically popular in the South Asian and Southeast Asian cultures.[14][15][16] His ancient legends have attracted bhasya (commentaries) and extensive secondary literature and inspired performance arts. Two such texts, for example, are the Adhyatma Ramayana – a spiritual and theological treatise considered foundational by Ramanandi monasteries,[17] and the Ramcharitmanas – a popular treatise that inspires thousands of Ramlila festival performances during autumn every year in India.[18][19][20]

Rama legends are also found in the texts of Jainism and Buddhism, though he is sometimes called Pauma or Padma in these texts,[21] and their details vary significantly from the Hindu versions.[22]

Etymology and nomenclature

Rāma is a Vedic Sanskrit word with two contextual meanings. In one context as found in Atharva Veda, as stated by Monier Monier-Williams, means "dark, dark-colored, black" and is related to the term ratri which means night. In another context as found in other Vedic texts, the word means "pleasing, delightful, charming, beautiful, lovely".[23][24] The word is sometimes used as a suffix in different Indian languages and religions, such as Pali in Buddhist texts, where -rama adds the sense of "pleasing to the mind, lovely" to the composite word.[25]

Rama as a first name appears in the Vedic literature, associated with two patronymic names – Margaveya and Aupatasvini – representing different individuals. A third individual named Rama Jamadagnya is the purported author of hymn 10.110 of the Rigveda in the Hindu tradition.[23] The word Rama appears in ancient literature in reverential terms for three individuals:[23]

1. Parashu-rama, as the sixth avatar of Vishnu. He is linked to the Rama Jamadagnya of the Rigveda fame.

2. Rama-chandra, as the seventh avatar of Vishnu and of the ancient Ramayana fame.

3. Bala-rama, also called Halayudha, as the elder brother of Krishna both of whom appear in the legends of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

The name Rama appears repeatedly in Hindu texts, for many different scholars and kings in mythical stories.[23] The word also appears in ancient Upanishads and Aranyakas layer of Vedic literature, as well as music and other post-Vedic literature, but in qualifying context of something or someone who is "charming, beautiful, lovely" or "darkness, night".[23]

The Vishnu avatar named Rama is also known by other names. He is called Ramachandra (beautiful, lovely moon),[24] or Dasarathi (son of Dasaratha), or Raghava (descendant of Raghu, solar dynasty in Hindu cosmology).[23][26] He is also known as Ram Lalla (Infant form of Rama).[27]

Additional names of Rama include Ramavijaya (Javanese), Phreah Ream (Khmer), Phra Ram (Lao and Thai), Megat Seri Rama (Malay), Raja Bantugan (Maranao), Ramudu (Telugu), Ramar (Tamil).[28] In the Vishnu sahasranama, Rama is the 394th name of Vishnu. In some Advaita Vedanta inspired texts, Rama connotes the metaphysical concept of Supreme Brahman who is the eternally blissful spiritual Self (Atman, soul) in whom yogis delight nondualistically.[29]

The root of the word Rama is ram- which means "stop, stand still, rest, rejoice, be pleased".[24]

According to Douglas Q. Adams, the Sanskrit word Rama is also found in other Indo-European languages such as Tocharian ram, reme, *romo- where it means "support, make still", "witness, make evident".[24][30] The sense of "dark, black, soot" also appears in other Indo European languages, such as *remos or Old English romig.[31][β]

Legends

This summary is a traditional legendary account, based on literary details from the Ramayana and other historic mythology-containing texts of Buddhism and Jainism. According to Sheldon Pollock, the figure of Rama incorporates more ancient "morphemes of Indian myths", such as the mythical legends of Bali and Namuci. The ancient sage Valmiki used these morphemes in his Ramayana similes as in sections 3.27, 3.59, 3.73, 5.19 and 29.28.[33]

Birth

Gold carving depiction of the legendary Ayodhya at the Ajmer Jain temple.

Rama was born on the ninth day of the lunar month Chaitra (March–April), a day celebrated across India as Ram Navami. This coincides with one of the four Navaratri on the Hindu calendar, in the spring season, namely the Vasantha Navaratri.[34]

The ancient epic Ramayana states in the Balakhanda that Rama and his brothers were born to Kaushalya and Dasharatha in Ayodhya, a city on the banks of Sarayu River.[35][36] The Jain versions of the Ramayana, such as the Paumacariya (literally deeds of Padma) by Vimalasuri, also mention the details of the early life of Rama. The Jain texts are dated variously, but generally pre-500 CE, most likely sometime within the first five centuries of the common era.[37] Moriz Winternitz states that the Valmiki Ramayana was already famous before it was recast in the Jain Paumacariya poem, dated to the second half of the 1st century, which pre-dates a similar retelling found in the Buddha-carita of Asvagosa, dated to the beginning of the 2:nd century or prior.[38]

Dasharatha was the king of Kosala, and a part of the solar dynasty of Iksvakus. His mother's name Kaushalya literally implies that she was from Kosala. The kingdom of Kosala is also mentioned in Buddhist and Jain texts, as one of the sixteen Maha janapadas of ancient India, and as an important center of pilgrimage for Jains and Buddhists.[35][39] However, there is a scholarly dispute whether the modern Ayodhya is indeed the same as the Ayodhya and Kosala mentioned in the Ramayana and other ancient Indian texts.[40][γ]

Youth, family and friends

Main articles: Bharata (Ramayana), Lakshmana, and Shatrughna

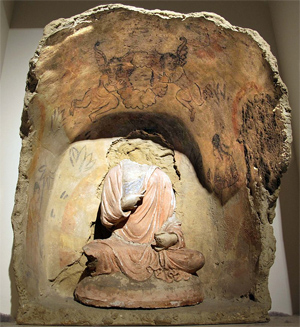

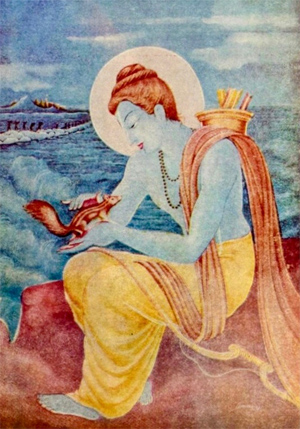

Rama is portrayed in Hindu arts and texts as a compassionate person who cares for all living beings.[42]

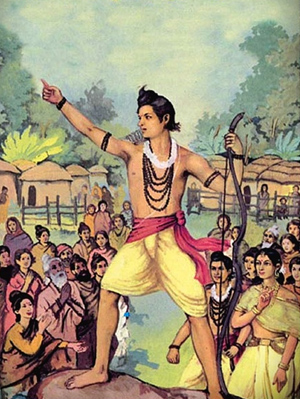

Rama had three brothers, according to the Balakhanda section of the Ramayana. These were Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna.[3] The extant manuscripts of the text describes their education and training as young princes, but this is brief. Rama is portrayed as a polite, self-controlled, virtuous youth always ready to help others. His education included the Vedas, the Vedangas as well as the martial arts.[43]

The years when Rama grew up are described in much greater detail by later Hindu texts, such as the Ramavali by Tulsidas. The template is similar to those found for Krishna, but in the poems of Tulsidas, Rama is milder and reserved introvert, rather than the prank-playing extrovert personality of Krishna.[3]

The Ramayana mentions an archery contest organised by King Janaka, where Sita and Rama meet. Rama wins the contest, whereby Janaka agrees to the marriage of Sita and Rama. Sita moves with Rama to his father Dashratha's capital.[3] Sita introduces Rama's brothers to her sister and her two cousins, and they all get married.[43]

While Rama and his brothers were away, Kaikeyi, the mother of Bharata and the second wife of King Dasharatha, reminds the king that he had promised long ago to comply with one thing she asks, anything. Dasharatha remembers and agrees to do so. She demands that Rama be exiled for fourteen years to Dandaka forest.[43] Dasharatha grieves at her request. Her son Bharata, and other family members become upset at her demand. Rama states that his father should keep his word, adds that he does not crave for earthly or heavenly material pleasures, neither seeks power nor anything else. He talks about his decision with his wife and tells everyone that time passes quickly. Sita leaves with him to live in the forest, the brother Lakshmana joins them in their exile as the caring close brother.[43]

Exile and war

See also: Ravana, Jatayu (Ramayana), Hanuman, and Vibheeshana

Rama, along with his younger brother Lakshmana and wife Sita, exiled to the forest.

Rama in Forest

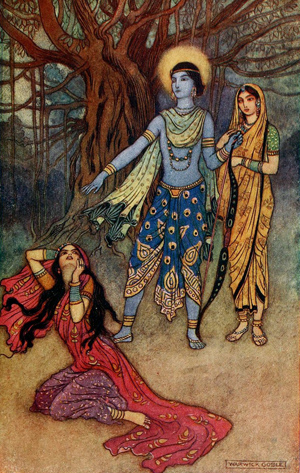

Ravana's sister Suparnakha attempts to seduce Rama and cheat on Sita. He refuses and spurns her (above).

Ravana kidnapping Sita while Jatayu on the left tried to help her. 9th-century Prambanan bas-relief, Java, Indonesia.

Hanuman meets Rama in the forest.

Rama heads outside the Kosala kingdom, crosses Yamuna river and initially stays at Chitrakuta, on the banks of river Mandakini, in the hermitage of sage Vasishtha.[44] During the exile, Rama meets one of his devotee, Shabari who happened to love him so much that when Rama asked something to eat she offered her ber, a fruit. But every time she gave it to him she first tasted it to ensure, it was sweet and tasty. Such was the level of her devotion. Rama also understood her devotion and ate all the half-eaten bers given by her. Such was the reciprocation of love and compassion he had for his people. This place is believed in the Hindu tradition to be the same as Chitrakoot on the border of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The region has numerous Rama temples and is an important Vaishnava pilgrimage site.[44] The texts describe nearby hermitages of Vedic rishis (sages) such as Atri, and that Rama roamed through forests, lived a humble simple life, provided protection and relief to ascetics in the forest being harassed and persecuted by demons, as they stayed at different ashrams.[44][45]

After ten years of wandering and struggles, Rama arrives at Panchavati, on the banks of river Godavari. This region had numerous demons (rakshashas). One day, a demoness called Shurpanakha saw Rama, became enamored of him, and tried to seduce him.[43] Rama refused her. Shurpanakha retaliated by threatening Sita. Lakshmana, the younger brother protective of his family, in turn retaliated by cutting off the nose and ears of Shurpanakha. The cycle of violence escalated, ultimately reaching demon king Ravana, who was the brother of Shurpanakha. Ravana comes to Panchavati to take revenge on behalf of his family, sees Sita, gets attracted, and kidnaps her to his kingdom of Lanka (believed to be modern Sri Lanka).[43][45]

Rama and Lakshmana discover the kidnapping, worry about Sita's safety, despair at the loss and their lack of resources to take on Ravana. Their struggles now reach new heights. They travel south, meet Sugriva, marshall an army of monkeys, and attract dedicated commanders such as Hanuman who was a minister of Sugriva.[46] Meanwhile, Ravana harasses Sita to be his wife, queen or goddess.[47] Sita refuses him. Ravana gets enraged and ultimately reaches Lanka, fights in a war that has many ups and downs, but ultimately Rama prevails, kills Ravana and forces of evil, and rescues his wife Sita. They return to Ayodhya.[43][48]

Post-war rule and death

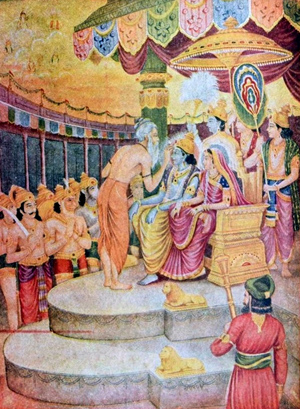

Scene from the Hindu epic poem the Ramayana - the return of the victors (chromolitho)

Rama Raj Tilak from Ramayana

The return of Rama to Ayodhya was celebrated with his coronation. It is called Rama pattabhisheka, and his rule itself as Rama rajya described to be a just and fair rule.[49][50] It is believed by many that when Rama returned people celebrated their happiness with diyas (lamps), and the festival of Diwali is connected with Rama's return.[51]

Upon Rama's accession as king, rumors emerge that Sita may have gone willingly when she was with Ravana; Sita protests that her capture was forced. Rama responds to public gossip by renouncing his wife and asking her to undergo a test before Agni (fire). She does and passes the test. Rama and Sita live happily together in Ayodhya, have twin sons named Luv and Kush, in the Ramayana and other major texts.[45] However, in some revisions, the story is different and tragic, with Sita dying of sorrow for her husband not trusting her, making Sita a moral heroine and leaving the reader with moral questions about Rama.[52][53] In these revisions, the death of Sita leads Rama to drown himself. Through death, he joins her in afterlife.[54] Rama dying by drowning himself is found in the Myanmar version of Rama's life story called Thiri Rama.[55]

Inconsistencies

Rama's legends vary significantly by the region and across manuscripts. While there is a common foundation, plot, grammar and an essential core of values associated with a battle between good and evil, there is neither a correct version nor a single verifiable ancient one. According to Paula Richman, there are hundreds of versions of "the story of Rama in India, Southeast Asia and beyond".[56][57] The versions vary by region reflecting local preoccupations and histories, and these cannot be called "divergences or different tellings" from the "real" version, rather all the versions of Rama story are real and true in their own meanings to the local cultural tradition, according to scholars such as Richman and Ramanujan.[56]

The stories vary in details, particularly where the moral question is clear, but the appropriate ethical response is unclear or disputed.[58][59] For example, when demoness Shurpanakha disguises as a woman to seduce Rama, then stalks and harasses Rama's wife Sita after Rama refuses her, Lakshmana is faced with the question of appropriate ethical response. In the Indian tradition, states Richman, the social value is that "a warrior must never harm a woman".[58] The details of the response by Rama and Lakshmana, and justifications for it, has numerous versions. Similarly, there are numerous and very different versions to how Rama deals with rumours against Sita when they return victorious to Ayodhya, given that the rumours can neither be objectively investigated nor summarily ignored.[60] Similarly the versions vary on many other specific situations and closure such as how Rama, Sita and Lakshmana die.[58][61]

The variation and inconsistencies are not limited to the texts found in the Hinduism traditions. The Rama story in the Jainism tradition also show variation by author and region, in details, in implied ethical prescriptions and even in names – the older versions using the name Padma instead of Rama, while the later Jain texts just use Rama.[62]

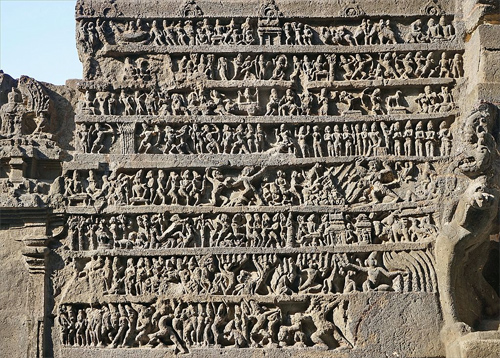

Dating

The Rama story is carved into stone as an 8th-century relief artwork in the largest Shiva temple of the Ellora Caves, suggesting its importance to the Indian society by then.[63]

In some Hindu texts, Rama is stated to have lived in the Treta Yuga[64] that their authors estimate existed before about 5,000 BCE. A few other researchers place Rama to have more plausibly lived around 1250 BCE,[65] based on regnal lists of Kuru and Vrishni leaders which if given more realistic reign lengths would place Bharat and Satwata, contemporaries of Rama, around that period. According to Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia, an Indian archaeologist, who specialised in Proto- and Ancient Indian history, this is all "pure speculation".[66]

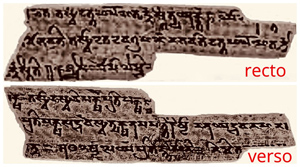

The composition of Rama's epic story, the Ramayana, in its current form is usually dated between 7th and 4th century BCE.[67][68] According to John Brockington, a professor of Sanskrit at Oxford known for his publications on the Ramayana, the original text was likely composed and transmitted orally in more ancient times, and modern scholars have suggested various centuries in the 1st millennium BCE. In Brockington's view, "based on the language, style and content of the work, a date of roughly the fifth century BCE is the most reasonable estimate".[69]

1870 painting on mica entitled, "Incarnation of Vishnu"

Appearance

Valmiki in Ramayana describes Rama as a charming, well built person of a dark complexion (varṇam śyāmam) and long arms (ājānabāhu, meaning a person who's middle finger reaches beyond their knee).[70] In the Sundara Kanda section of the epic, Hanuman describes Rama to Sita when she is held captive in Lanka to prove to her that he is indeed a messenger from Rama:

He has broad shoulders, mighty arms, a conch-shaped neck, a charming countenance, and coppery eyes;

he has his clavicle concealed and is known by the people as Rama. He has a voice (deep) like the sound of a kettledrum and glossy skin,

is full of glory, square-built, and of well-proportioned limbs and is endowed with a dark-brown complexion.[71]

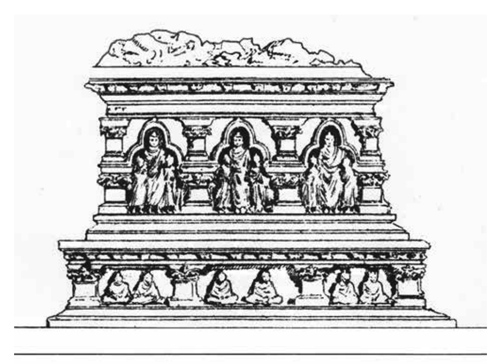

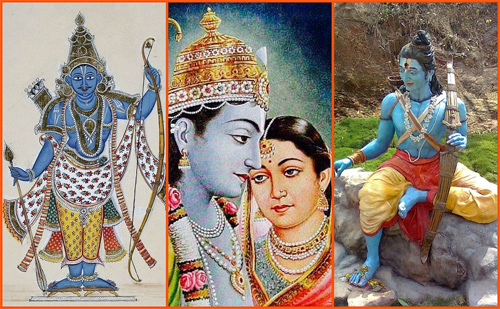

Iconography

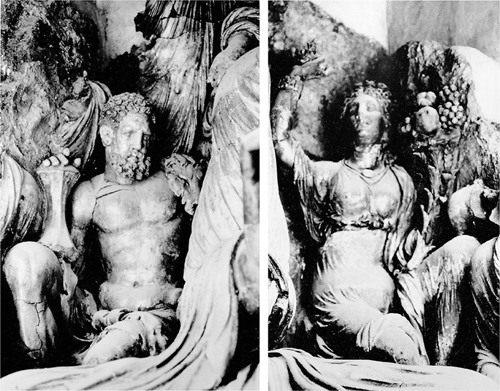

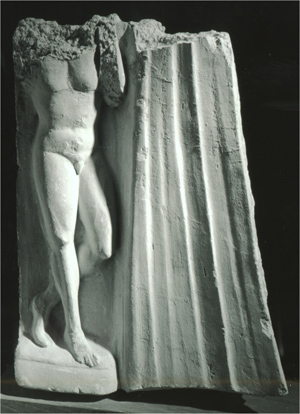

Rama iconography widely varies, and typically show him in context of some legend.

Rama iconography shares elements of Vishnu avatars, but has several distinctive elements. It never has more than two hands, he holds (or has nearby) a bana (arrow) in his right hand, while he holds the dhanus (bow) in his left.[72] The most recommended icon for him is that he be shown standing in tribhanga pose (thrice bent "S" shape). He is shown black, blue or dark color, typically wearing reddish color clothes. If his wife and brother are a part of the iconography, Lakshamana is on his left side while Sita always on the right of Rama, both of golden-yellow complexion.[72]

Philosophy and symbolism

Rama's life story is imbued with symbolism. According to Sheldon Pollock, the life of Rama as told in the Indian texts is a masterpiece that offers a framework to represent, conceptualise and comprehend the world and the nature of life. Like major epics and religious stories around the world, it has been of vital relevance because it "tells the culture what it is". Rama's life is more complex than the Western template for the battle between the good and the evil, where there is a clear distinction between immortal powerful gods or heroes and mortal struggling humans. In the Indian traditions, particularly Rama, the story is about a divine human, a mortal god, incorporating both into the exemplar who transcends both humans and gods.[73]

Responding to evil

A superior being does not render evil for evil,

this is the maxim one should observe;

the ornament of virtuous persons is their conduct.

(...)

A noble soul will ever exercise compassion

even towards those who enjoy injuring others.

—Ramayana 6.115, Valmiki

(Abridged, Translator: Roderick Hindery)[74]

As a person, Rama personifies the characteristics of an ideal person (purushottama).[53] He had within him all the desirable virtues that any individual would seek to aspire, and he fulfils all his moral obligations. Rama is considered a maryada purushottama or the best of upholders of Dharma.[75]

According to Rodrick Hindery, Book 2, 6 and 7 are notable for ethical studies.[76][59] The views of Rama combine "reason with emotions" to create a "thinking hearts" approach. Second, he emphasises through what he says and what he does a union of "self-consciousness and action" to create an "ethics of character". Third, Rama's life combines the ethics with the aesthetics of living.[76] The story of Rama and people in his life raises questions such as "is it appropriate to use evil to respond to evil?", and then provides a spectrum of views within the framework of Indian beliefs such as on karma and dharma.[74]

Rama's life and comments emphasise that one must pursue and live life fully, that all three life aims are equally important: virtue (dharma), desires (kama), and legitimate acquisition of wealth (artha). Rama also adds, such as in section 4.38 of the Ramayana, that one must also introspect and never neglect what one's proper duties, appropriate responsibilities, true interests, and legitimate pleasures are.[42]

Literary sources

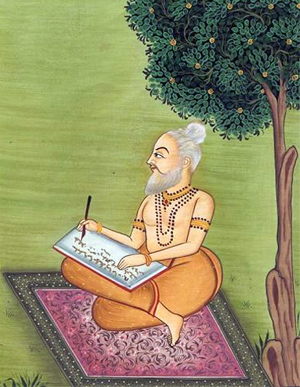

Valmiki composing the Ramayana.

Ramayana

The primary source of the life of Rama is the Sanskrit epic Ramayana composed by Rishi Valmiki.[77]

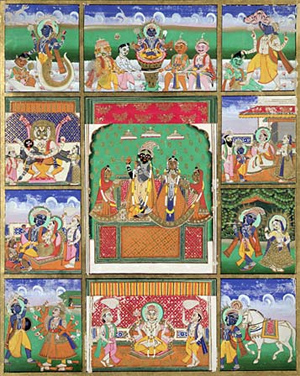

Rama (left third from top) depicted in the Dashavatara (ten incornations) of Vishnu. Painting from Jaipur, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum

The epic had many versions across India's regions. The followers of Madhvacharya believe that an older version of the Ramayana, the Mula-Ramayana, previously existed.[78] The Madhva tradition considers it to have been more authoritative than the version by Valmiki.[79]

Versions of the Ramayana exist in most major Indian languages; examples that elaborate on the life, deeds and divine philosophies of Rama include the epic poem Ramavataram, and the following vernacular versions of Rama's life story:[80]

• Ramavataram or Kamba-Ramayanam in Tamil by the poet Kambar in Tamil. (12th century)

• Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese by poet Madhava Kandali. (14th century)

• Krittivasi Ramayan in Bengali by poet Krittibas Ojha. (15th century)

• Ramcharitmanas in Hindi by sant Tulsidas. (16th-century)

• Pampa Ramayana, Torave Ramayana by Kumara Valmiki and Sri Ramayana Darshanam by Kuvempu in Kannada;

• Ramayana Kalpavruksham by Viswanatha Satyanarayana and Ramayana by Ranganatha in Telugu;

• Vilanka Ramayana in Odia;

• Eluttachan in Malayalam (this text is closer to the Advaita Vedanta-inspired rendition Adhyatma Ramayana).[81]

The epic is found across India, in different languages and cultural traditions.[82]

Adhyatma Ramayana

Adhyatma Ramayana is a late medieval Sanskrit text extolling the spiritualism in the story of Ramayana. It is embedded in the latter portion of Brahmānda Purana, and constitutes about a third of it.[83] The text philosophically attempts to reconcile Bhakti in god Rama and Shaktism with Advaita Vedanta, over 65 chapters and 4,500 verses.[84][85]

The text represents Rama as the Brahman (metaphysical reality), mapping all attributes and aspects of Rama to abstract virtues and spiritual ideals.[85] Adhyatma Ramayana transposes Ramayana into symbolism of self study of one's own soul, with metaphors described in Advaita terminology.[85] The text is notable because it influenced the popular Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas,[83][85] and inspired the most popular version of Nepali Ramayana by Bhanubhakta Acharya.[86] This was also translated by Thunchath Ezhuthachan to Malayalam, which lead the foundation of Malayalam literature itself.[87]

Ramacharitmanas

The Ramayana is a Sanskrit text, while Ramacharitamanasa retells the Ramayana in a vernacular dialect of Hindi language,[88] commonly understood in northern India.[89][90][91] Ramacharitamanasa was composed in the 16th century by Tulsidas.[92][93][88] The popular text is notable for synthesising the epic story in a Bhakti movement framework, wherein the original legends and ideas morph in an expression of spiritual bhakti (devotional love) for a personal god.[88][94][δ]

Tulsidas was inspired by Adhyatma Ramayana, where Rama and other characters of the Valmiki Ramayana along with their attributes (saguna narrative) were transposed into spiritual terms and abstract rendering of an Atma (soul, self, Brahman) without attributes (nirguna reality).[83][85][96] According to Kapoor, Rama's life story in the Ramacharitamanasa combines mythology, philosophy, and religious beliefs into a story of life, a code of ethics, a treatise on universal human values.[97] It debates in its dialogues the human dilemmas, the ideal standards of behaviour, duties to those one loves, and mutual responsibilities. It inspires the audience to view their own lives from a spiritual plane, encouraging the virtuous to keep going, and comforting those oppressed with a healing balm.[97]

The Ramacharitmanas is notable for being the Rama-based play commonly performed every year in autumn, during the weeklong performance arts festival of Ramlila.[20] The "staging of the Ramayana based on the Ramacharitmanas" was inscribed in 2008 by UNESCO as one of the Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity.[98]

Yoga Vasistha

Main article: Yoga Vasistha

Human effort can be used for self-betterment and that there is no such thing as an external fate imposed by the gods.

– Yoga Vasistha (Vasistha teaching Rama)

Tr: Christopher Chapple[99]

Yoga Vasistha is a Sanskrit text structured as a conversation between young Prince Rama and sage Vasistha who was called as the first sage of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy by Adi Shankara. The complete text contains over 29,000 verses.[100] The short version of the text is called Laghu Yogavasistha and contains 6,000 verses.[101] The exact century of its completion is unknown, but has been estimated to be somewhere between the 6:th century to as late as the 14:th century, but it is likely that a version of the text existed in the 1:st millennium.[102]

The Yoga Vasistha text consists of six books. The first book presents Rama's frustration with the nature of life, human suffering and disdain for the world. The second describes, through the character of Rama, the desire for liberation and the nature of those who seek such liberation. The third and fourth books assert that liberation comes through a spiritual life, one that requires self-effort, and present cosmology and metaphysical theories of existence embedded in stories.[103] These two books are known for emphasising free will and human creative power.[103][104] The fifth book discusses meditation and its powers in liberating the individual, while the last book describes the state of an enlightened and blissful Rama.[103][105]

Yoga Vasistha is considered one of the most important texts of the Vedantic philosophy.[106] The text, states David Gordon White, served as a reference on Yoga for medieval era Advaita Vedanta scholars.[107] The Yoga Vasistha, according to White, was one of the popular texts on Yoga that dominated the Indian Yoga culture scene before the 12th century.[107]

Other texts

Other important historic Hindu texts on Rama include Bhusundi Ramanaya, Prasanna raghava, and Ramavali by Tulsidas.[3][108] The Sanskrit poem Bhaṭṭikāvya of Bhatti, who lived in Gujarat in the seventh century CE, is a retelling of the epic that simultaneously illustrates the grammatical examples for Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī as well as the major figures of speech and the Prakrit language.[109]

Another historically and chronologically important text is Raghuvamsa authored by Kalidasa.[110] Its story confirms many details of the Ramayana, but has novel and different elements. It mentions that Ayodhya was not the capital in the time of Rama's son named Kusha, but that he later returned to it and made it the capital again. This text is notable because the poetry in the text is exquisite and called a Mahakavya in the Indian tradition, and has attracted many scholarly commentaries. It is also significant because Kalidasa has been dated to between the 4th and 5th century CE, suggesting that the Ramayana legend was well established by the time of Kalidasa.[110]

The Mahabharata has a summary of the Ramayana. The Jainism tradition has extensive literature of Rama as well, but generally refers to him as Padma, such as in the Paumacariya by Vimalasuri.[37] Rama and Sita legend is mentioned in the Jataka tales of Buddhism, as Dasaratha-Jataka (Tale no. 461), but with slightly different spellings such as Lakkhana for Lakshmana and Rama-pandita for Rama.[111][112][113]

The chapter 4 of Vishnu Purana, chapter 112 of Padma Purana, chapter 143 of Garuda Purana and chapters 5 through 11 of Agni Purana also summarise the life story of Rama.[114] Additionally, the Rama story is included in the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata, which has been a part of evidence that the Ramayana is likely more ancient, and it was summarised in the Mahabharata epic in ancient times.[115]

Influence

Rama (Yama) and Sita (Thida) in Yama Zatdaw, the Burmese version of the Ramayana

Rama's story has had a major socio-cultural and inspirational influence across South Asia and Southeast Asia.[14][116]

Few works of literature produced in any place at any time have been as popular, influential, imitated and successful as the great and ancient Sanskrit epic poem, the Valmiki Ramayana.

– Robert Goldman, Professor of Sanskrit, University of California at Berkeley.[14]

According to Arthur Anthony Macdonell, a professor at Oxford and Boden scholar of Sanskrit, Rama's ideas as told in the Indian texts are secular in origin, their influence on the life and thought of people having been profound over at least two and a half millennia.[117][118] Their influence has ranged from being a framework for personal introspection to cultural festivals and community entertainment.[14] His life stories, states Goldman, have inspired "painting, film, sculpture, puppet shows, shadow plays, novels, poems, TV serials and plays."[117]

Hinduism

See also: List of Hindu festivals

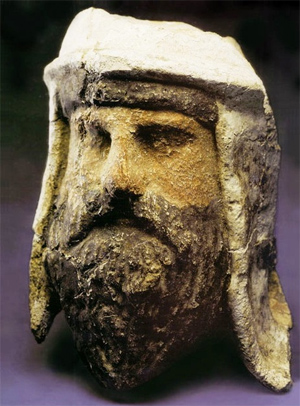

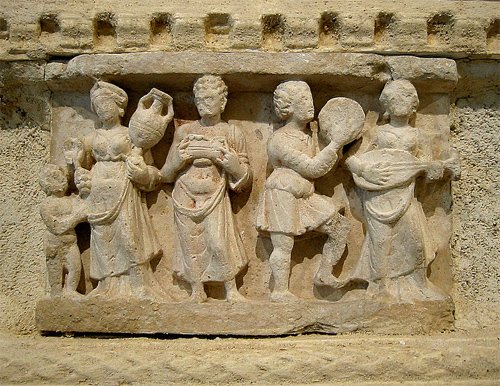

A 5th century terracotta sculpture depicting Rama.

Rama Navami

Main article: Rama Navami

Rama Navami is a spring festival that celebrates the birthday of Rama. The festival is a part of the spring Navratri, and falls on the ninth day of the bright half of Chaitra month in the traditional Hindu calendar. This typically occurs in the Gregorian months of March or April every year.[119][120]

The day is marked by recital of Rama legends in temples, or reading of Rama stories at home. Some Vaishnava Hindus visit a temple, others pray within their home, and some participate in a bhajan or kirtan with music as a part of puja and aarti.[121] The community organises charitable events and volunteer meals. The festival is an occasion for moral reflection for many Hindus.[122][123] Some mark this day by vrata (fasting) or a visit to a river for a dip.[122][124][125]

The important celebrations on this day take place at Ayodhya, Sitamarhi,[126] Janakpurdham (Nepal), Bhadrachalam, Kodandarama Temple, Vontimitta and Rameswaram. Rathayatras, the chariot processions, also known as Shobha yatras of Rama, Sita, his brother Lakshmana and Hanuman, are taken out at several places.[122][127][128] In Ayodhya, many take a dip in the sacred river Sarayu and then visit the Rama temple.[125]

Rama Navami day also marks the end of the nine-day spring festival celebrated in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh called Vasanthothsavam (Festival of Spring), that starts with Ugadi. Some highlights of this day are Kalyanam (ceremonial wedding performed by temple priests) at Bhadrachalam on the banks of the river Godavari in Bhadradri Kothagudem district of Telangana, preparing and sharing Panakam which is a sweet drink prepared with jaggery and pepper, a procession and Rama temple decorations.[129]